Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Opioids

Uploaded by

Nia TowneCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Opioids

Uploaded by

Nia TowneCopyright:

Available Formats

CDC GUIDELINE FOR PRESCRIBING

OPIOIDS FOR CHRONIC PAIN

Promoting Patient Care and Safety

THE US OPIOID OVERDOSE EPIDEMIC

The United States is in the midst of an epidemic of prescription opioid overdoses. The amount

of opioids prescribed and sold in the US quadrupled since 1999, but the overall amount of pain

reported by Americans hasnt changed. This epidemic is devastating American lives, families,

and communities.

40

More than 40 people die every day from

overdoses involving prescription opioids.1

165K

Since 1999, there have been over

165,000 deaths from overdose related

to prescription opioids.1

PRESCRIPTION OPIOIDS HAVE

BENEFITS AND RISKS

249M

4.3M

4.3 million Americans engaged in

non-medical use of prescription

opioids in the last month.2

prescriptions for opioid pain

medication were written by

healthcare providers in 2013

Many Americans suffer from chronic

pain. These patients deserve safe

and effective pain management.

Prescription opioids can help manage

some types of pain in the short term.

However, we dont have enough

information about the benefits of

opioids long term, and we know that

enough prescriptions were written for every

American adult to have a bottle of pills

there are serious risks of opioid use

disorder and overdoseparticularly

with high dosages and long-term use.

Includes overdose deaths related to methadone but does not include overdose deaths related to other synthetic

prescription opioids such as fentanyl.

National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 2014

L E A R N M O R E | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

NEW CDC GUIDELINE WILL HELP IMPROVE CARE, REDUCE RISKS

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

developed the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids

for Chronic Pain (Guideline) for primary care clinicians

treating adult patients for chronic pain in outpatient

settings. The Guideline is not intended for patients who are

in active cancer treatment, palliative care, or end-of-life

care. The Guideline was developed to:

Improve communication between clinicians and patients

about the benefits and risks of using prescription opioids for

chronic pain

Provide safer, more effective care for patients with chronic pain

Help reduce opioid use disorder and overdose

As many as

1in 4

patients receiving long-term opioid

therapy in primary care settings

The Guideline provides recommendations to primary care

clinicians about the appropriate prescribing of opioids to

improve pain management and patient safety. It will:

Help clinicians determine if and when to start prescription

opioids for chronic pain

Give guidance about medication selection, dose, and

duration, and when and how to reassess progress, and

discontinue medication if needed

Help clinicians and patientstogetherassess the benefits

and risks of prescription opioid use

Among the 12 recommendations in the Guideline, there are

three principles that are especially important to improving

patient care and safety:

Nonopioid therapy is preferred for chronic pain outside

of active cancer, palliative, and end-of-life care.

When opioids are used, the lowest possible effective

dosage should be prescribed to reduce risks of opioid

use disorder and overdose.

Clinicians should always exercise caution when

prescribing opioids and monitor all patients closely.

To develop the Guideline, CDC followed a transparent and

rigorous scientific process using the best available scientific

evidence, consulting with experts, and listening to comments

from the public and partners.

struggle with opioid use disorder.

PATIENT CARE AND SAFETY IS

CENTRAL TO THE GUIDELINE

Before starting opioids to treat chronic pain,

patients should:

Make the most informed decision with their doctors

Learn about prescription opioids and know the risks

Consider ways to manage pain that do not include

opioids, such as:

-

Physical therapy

Exercise

Nonopioid medications, such as acetaminophen

or ibuprofen

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

L E A R N M O R E | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

CDC RECOMMENDATIONS

DETERMINING WHEN TO INITIATE OR CONTINUE OPIOIDS FOR CHRONIC PAIN

OPIOIDS ARE NOT FIRST-LINE THERAPY

Nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid pharmacologic therapy

are preferred for chronic pain. Clinicians should consider opioid

therapy only if expected benefits for both pain and function are

anticipated to outweigh risks to the patient. If opioids are used, they

should be combined with nonpharmacologic therapy and nonopioid

pharmacologic therapy, as appropriate.

Nonpharmacologic therapies and

nonopioid medications include:

Nonopioid medications such as

acetaminophen, ibuprofen, or certain

medications that are also used for

depression or seizures

ESTABLISH GOALS FOR PAIN AND FUNCTION

Physical treatments (eg, exercise

therapy, weight loss)

Behavioral treatment (eg, CBT)

Interventional treatments

(eg, injections)

Before starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should

establish treatment goals with all patients, including realistic goals

for pain and function, and should consider how opioid therapy

will be discontinued if benefits do not outweigh risks. Clinicians

should continue opioid therapy only if there is clinically meaningful

improvement in pain and function that outweighs risks to patient safety.

DISCUSS RISKS AND BENEFITS

Before starting and periodically during opioid therapy, clinicians should discuss with patients known risks and

realistic benefits of opioid therapy and patient and clinician responsibilities for managing therapy.

OPIOID SELECTION, DOSAGE, DURATION, FOLLOW-UP, AND DISCONTINUATION

4

5

USE IMMEDIATE-RELEASE OPIOIDS WHEN STARTING

When starting opioid therapy for chronic pain, clinicians should

prescribe immediate-release opioids instead of extended-release/

long-acting (ER/LA) opioids.

USE THE LOWEST EFFECTIVE DOSE

When opioids are started, clinicians should prescribe the lowest

effective dosage. Clinicians should use caution when prescribing

opioids at any dosage, should carefully reassess evidence of

individual benefits and risks when considering increasing dosage to

50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME)/day, and should avoid

increasing dosage to 90 MME/day or carefully justify a decision to

titrate dosage to 90 MME/day.

PRESCRIBE SHORT DURATIONS FOR ACUTE PAIN

Long-term opioid use often begins with treatment of acute pain.

When opioids are used for acute pain, clinicians should prescribe

the lowest effective dose of immediate-release opioids and should

prescribe no greater quantity than needed for the expected duration

of pain severe enough to require opioids. Three days or less will

often be sufficient; more than seven days will rarely be needed.

Immediate-release opioids: faster

acting medication with a shorter

duration of pain-relieving action

Extended release opioids: slower

acting medication with a longer

duration of pain-relieving action

Morphine milligram equivalents

(MME)/day: the amount of morphine

an opioid dose is equal to when

prescribed, often used as a gauge of

the abuse and overdose potential of the

amount of opioid that is being given at

a particular time

L E A R N M O R E | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

EVALUATE BENEFITS AND HARMS FREQUENTLY

Clinicians should evaluate benefits and harms with patients within 1 to 4 weeks of starting opioid therapy for

chronic pain or of dose escalation. Clinicians should evaluate benefits and harms of continued therapy with

patients every 3 months or more frequently. If benefits do not outweigh harms of continued opioid therapy,

clinicians should optimize other therapies and work with patients to taper opioids to lower dosages or to taper

and discontinue opioids.

ASSESSING RISK AND ADDRESSING HARMS

10

11

12

USE STRATEGIES TO MITIGATE RISK

Before starting and periodically during continuation of opioid

therapy, clinicians should evaluate risk factors for opioid-related

harms. Clinicians should incorporate into the management

plan strategies to mitigate risk, including considering offering

naloxone when factors that increase risk for opioid overdose,

such as history of overdose, history of substance use disorder,

higher opioid dosages (50 MME/day), or concurrent

benzodiazepine use, are present.

Naloxone: a drug that can reverse the

effects of opioid overdose

Benzodiazepine: sometimes called

benzo, is a sedative often used to treat

anxiety, insomnia, and other conditions

REVIEW PDMP DATA

Clinicians should review the patients history of controlled

substance prescriptions using state prescription drug monitoring

program (PDMP) data to determine whether the patient is

receiving opioid dosages or dangerous combinations that put

him or her at high risk for overdose. Clinicians should review

PDMP data when starting opioid therapy for chronic pain and

periodically during opioid therapy for chronic pain, ranging

from every prescription to every 3 months.

USE URINE DRUG TESTING

When prescribing opioids for chronic pain, clinicians should

use urine drug testing before starting opioid therapy and

consider urine drug testing at least annually to assess for

prescribed medications as well as other controlled prescription

drugs and illicit drugs.

PDMP: a prescription drug monitoring

program is a statewide electronic

database that tracks all controlled

substance prescriptions

NEARLY

2M

AVOID CONCURRENT OPIOID AND

BENZODIAZEPINE PRESCRIBING

Clinicians should avoid prescribing opioid pain medication and

benzodiazepines concurrently whenever possible.

OFFER TREATMENT FOR OPIOID USE DISORDER

Clinicians should offer or arrange evidence-based treatment

(usually medication-assisted treatment with buprenorphine

or methadone in combination with behavioral therapies) for

patients with opioid use disorder.

Americans, aged 12 or older,

either abused or were dependent on

prescription opioids in 2014

Medication-assisted treatment:

treatment for opioid use disorder

including medications such as

buprenorphine or methadone

L E A R N M O R E | www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/prescribing/guideline.html

You might also like

- Family Survivor ChecklistDocument1 pageFamily Survivor ChecklistNia TowneNo ratings yet

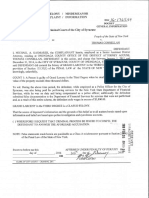

- City of Syracuse Common CouncilDocument2 pagesCity of Syracuse Common CouncilNia TowneNo ratings yet

- 3-26-16 LTR To Judge Sherwood-Amanda HellmannDocument2 pages3-26-16 LTR To Judge Sherwood-Amanda HellmannNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Kopp & Oberst Complaint ArrestDocument1 pageKopp & Oberst Complaint ArrestNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Manufacturing Short Factsheet 3.31.2016Document4 pagesManufacturing Short Factsheet 3.31.2016Nia TowneNo ratings yet

- Kopp & Oberst Complaint ArrestDocument1 pageKopp & Oberst Complaint ArrestNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Kopp - Oberst Indictment Press Release (Final)Document2 pagesKopp - Oberst Indictment Press Release (Final)Nia TowneNo ratings yet

- Letter Home Re Threat-Blocked EmailsDocument1 pageLetter Home Re Threat-Blocked EmailsNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Kopp Oberst Federal IndictmentDocument7 pagesKopp Oberst Federal IndictmentNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Barry PetitionDocument94 pagesBarry PetitionNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Letter To All Saints ParentsDocument1 pageLetter To All Saints ParentsNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Ryan Lawrence IndictmentDocument2 pagesRyan Lawrence IndictmentNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Anthony Vita Criminal ComplaintDocument7 pagesAnthony Vita Criminal ComplaintNia TowneNo ratings yet

- David SpragueDocument1 pageDavid SpragueNia TowneNo ratings yet

- H 1226971Document1 pageH 1226971Nia TowneNo ratings yet

- Jacob Rollins-Young Court Docs (Redacted)Document9 pagesJacob Rollins-Young Court Docs (Redacted)Nia TowneNo ratings yet

- EasterEggHunt Email MPDocument1 pageEasterEggHunt Email MPNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Jacob Rollins-Young (Redacted)Document9 pagesJacob Rollins-Young (Redacted)Nia TowneNo ratings yet

- 2016 3 8 Tourism MappingDocument1 page2016 3 8 Tourism MappingNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Paige Sharp Missing Person PosterDocument1 pagePaige Sharp Missing Person PosterNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Paige Sharp Missing Person PosterDocument1 pagePaige Sharp Missing Person PosterNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Community Letter Re-Water, March 3, 2016Document1 pageCommunity Letter Re-Water, March 3, 2016Nia TowneNo ratings yet

- Oswego Co. DA Statement On Thibodeau RulingDocument1 pageOswego Co. DA Statement On Thibodeau RulingNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Health Depart March 3Document2 pagesHealth Depart March 3Nia TowneNo ratings yet

- Oswego Co. DA Statement On Thibodeau RulingDocument1 pageOswego Co. DA Statement On Thibodeau RulingNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Lawrence, Ryan Felony-ComplaintDocument1 pageLawrence, Ryan Felony-ComplaintSeth PalmerNo ratings yet

- Municipals March 3Document2 pagesMunicipals March 3Nia TowneNo ratings yet

- Lisa Buske Statement On RulingDocument2 pagesLisa Buske Statement On RulingNia TowneNo ratings yet

- Former Syracuse Officer and Katko Staffer Accused of Stealing From City, StateDocument3 pagesFormer Syracuse Officer and Katko Staffer Accused of Stealing From City, StateNia TowneNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Call SANROCCO 11 HappybirthdayBramanteDocument8 pagesCall SANROCCO 11 HappybirthdayBramanterod57No ratings yet

- 4 - Complex IntegralsDocument89 pages4 - Complex IntegralsryuzackyNo ratings yet

- EPF Passbook Details for Member ID RJRAJ19545850000014181Document3 pagesEPF Passbook Details for Member ID RJRAJ19545850000014181Parveen SainiNo ratings yet

- Interna Medicine RheumatologyDocument15 pagesInterna Medicine RheumatologyHidayah13No ratings yet

- City of Brescia - Map - WWW - Bresciatourism.itDocument1 pageCity of Brescia - Map - WWW - Bresciatourism.itBrescia TourismNo ratings yet

- 3.2 Probability DistributionDocument38 pages3.2 Probability Distributionyouservezeropurpose113No ratings yet

- Rescue Triangle PDFDocument18 pagesRescue Triangle PDFrabas_No ratings yet

- The Rich Hues of Purple Murex DyeDocument44 pagesThe Rich Hues of Purple Murex DyeYiğit KılıçNo ratings yet

- Lesson 5 CMADocument10 pagesLesson 5 CMAAssma SabriNo ratings yet

- Docking 1Document12 pagesDocking 1Naveen Virendra SinghNo ratings yet

- CV Abdalla Ali Hashish-Nursing Specialist.Document3 pagesCV Abdalla Ali Hashish-Nursing Specialist.Abdalla Ali HashishNo ratings yet

- Raychem Price ListDocument48 pagesRaychem Price ListramshivvermaNo ratings yet

- Ilham Bahasa InggrisDocument12 pagesIlham Bahasa Inggrisilhamwicaksono835No ratings yet

- Chapter 08Document18 pagesChapter 08soobraNo ratings yet

- ThesisDocument250 pagesThesislax mediaNo ratings yet

- Published Filer List 06072019 Sorted by CodeDocument198 pagesPublished Filer List 06072019 Sorted by Codeherveduprince1No ratings yet

- Hotel and Restaurant at Blue Nile FallsDocument26 pagesHotel and Restaurant at Blue Nile Fallsbig johnNo ratings yet

- A Systematic Scoping Review of Sustainable Tourism Indicators in Relation To The Sustainable Development GoalsDocument22 pagesA Systematic Scoping Review of Sustainable Tourism Indicators in Relation To The Sustainable Development GoalsNathy Slq AstudilloNo ratings yet

- Samsung 55 Inch LCD LED 8000 User ManualDocument290 pagesSamsung 55 Inch LCD LED 8000 User ManuallakedipperNo ratings yet

- E PortfolioDocument76 pagesE PortfolioMAGALLON ANDREWNo ratings yet

- Research Paper Theory of Mind 2Document15 pagesResearch Paper Theory of Mind 2api-529331295No ratings yet

- Chetan Bhagat's "Half GirlfriendDocument4 pagesChetan Bhagat's "Half GirlfriendDR Sultan Ali AhmedNo ratings yet

- All MeterialsDocument236 pagesAll MeterialsTamzid AhmedNo ratings yet

- Complete Hemi Sync Gateway Experience ManualDocument43 pagesComplete Hemi Sync Gateway Experience Manualapi-385433292% (92)

- Dell EMC VPLEX For All-FlashDocument4 pagesDell EMC VPLEX For All-Flashghazal AshouriNo ratings yet

- PM - Network Analysis CasesDocument20 pagesPM - Network Analysis CasesImransk401No ratings yet

- Mama Leone's Profitability AnalysisDocument6 pagesMama Leone's Profitability AnalysisLuc TranNo ratings yet

- Learning Online: Veletsianos, GeorgeDocument11 pagesLearning Online: Veletsianos, GeorgePsico XavierNo ratings yet

- Color Codes and Irregular Marking-SampleDocument23 pagesColor Codes and Irregular Marking-Samplemahrez laabidiNo ratings yet

- Marksmanship: Subject: III. Definition of TermsDocument16 pagesMarksmanship: Subject: III. Definition of TermsAmber EbayaNo ratings yet