Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Clean Vs Sterile Dressing Techniques For.7

Uploaded by

Putra EkaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Clean Vs Sterile Dressing Techniques For.7

Uploaded by

Putra EkaCopyright:

Available Formats

J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2012;39(2S):S30-S34.

Published by Lippincott Williams & Wilkins

Clean vs. Sterile Dressing

Techniques for Management

of Chronic Wounds

A Fact Sheet

Definition of terms

exist. Terms have been used interchangeably and all are

subject to individual interpretation. The following definitions provide a point of reference for the terms used in

this document.

Sterile technique. Sterile is generally defined as

meaning free from microorganisms.3 Sterile technique involves strategies used in patient care to reduce exposure to

microorganisms and maintain objects and areas as free

from microorganisms as possible. Sterile technique involves meticulous hand washing, use of a sterile field, use

of sterile gloves for application of a sterile dressing, and

use of sterile instruments. Sterile to sterile rules involve

the use of only sterile instruments and materials in dressing change procedures; and avoiding contact between

sterile instruments or materials and any non-sterile surface or products. Sterile technique is considered most appropriate in acute care hospital settings, for patients at

high risk for infection, and for certain procedures such as

sharp instrumental wound debridement.3-5

Clean technique. Clean means free of dirt, marks, or

stains.3 Clean technique involves strategies used in patient

care to reduce the overall number of microorganisms or to

prevent or reduce the risk of transmission of microorganisms from one person to another or from one place to another. Clean technique involves meticulous handwashing,

maintaining a clean environment by preparing a clean

field, using clean gloves and sterile instruments, and preventing direct contamination of materials and supplies.

No sterile to sterile rules apply. This technique may also

be referred to as non-sterile. Clean technique is considered

most appropriate for long-term care, home care, and some

clinic settings; for patients who are not at high risk for

infection; and for patients receiving routine dressings for

chronic wounds such as venous ulcers, or wounds healing

by secondary intention with granulation tissue.1-7

Aseptic technique. Asepsis or aseptic means free

from pathogenic microorganisms.3 Aseptic technique is

Clean versus sterile technique. Various definitions

and descriptions of dressing technique for wound care

DOI: 10.1097/WON.0b013e3182478e06

Originated By:

Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society (WOCN)

Wound Committee and the Association for Professionals

in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc. (APIC) 2000

Guidelines Committee

Updated/Revised: WOCN Wound Committee, 2011

Date Completed:

Original Publication Date: 2001

Review/Update: 2005

Revised: 2011

Purpose

To present an update on the status of information about

clean versus sterile dressing technique to manage chronic

wounds.

Background/History

This document originated in 2001 as a joint position statement from a collaborative effort of the Wound, Ostomy and

Continence Nurses Society and the Association for

Professionals in Infection Control and Epidemiology, Inc.1,2

Its purpose was to review the evidence about clean vs. sterile technique and present approaches for chronic wound

care management. Then as now, areas of controversy exist

due to a lack of agreement on the definitions of clean and

sterile technique, lack of consensus as to when each is

indicated in the management of chronic wounds, and lack

of research to serve as a guide. Wound care practices are

extremely variable and are frequently based on rituals and

traditions as opposed to a scientific foundation.

Discussion of Problems/Issue/Needs

S30 J WOCN March/April 2012

WON200342.indd S30

Copyright 2012 by the Wound, Ostomy and Continence Nurses Society

03/03/12 4:27 PM

J WOCN

Volume 39/Number 2S

the purposeful prevention of the transfer of organisms

from one person to another by keeping the microbe count

to an irreducible minimum. Some authors have made a

distinction between surgical asepsis or sterile technique

used in surgery and medical asepsis or clean technique

that involves procedures to reduce the number and transmission of pathogens.4

No touch technique. No touch is a method of changing surface dressings without directly touching the wound

or any surface that might come in contact with the wound.

Clean gloves are used along with sterile solution/supplies/

dressings that are maintained as clean.8

Definition of infection. Infection has been defined

as a continuum from contamination, colonization, critical

colonization, biofilm, and infection.9

Contamination. Contamination is the presence of

non-replicating microorganisms on the surface of the

wound. All open wounds have some level of bacterial burden that is ordinarily cleared by the host.9-11

Colonization. In colonization, microorganisms attach to the wound surface and replicate but do not impair

healing or cause signs and/or symptoms of infection. The

bacteria are not pathogenic and do not require treatment.

All chronic wounds are colonized to varying degrees.9

Critical colonization. With critical colonization,

the organisms attach to the wound surface, replicate and

multiply to a level that affects skin cell proliferation and

tissue repair without provoking systemic signs of infection. There is no invasion of the healthy tissue at this

point.9

Biofilm. Approximately 70% of chronic wounds have

biofilm.9 When organisms adhere to the wound surface,

they begin to develop biofilm, which is a complex system

of microorganisms embedded in an extracellular, polysaccharide matrix that protects from the invasion of other

organisms, phagocytosis, and many commonly used antibiotics and antiseptics. Biofilms are difficult to treat and

eradicate.9 Recently it has been proposed that biofilm

might be present in all chronic wounds.12,13

Infection. Infection occurs when organisms on the

wound surface invade the healthy tissue, reproduce, overwhelm the host resistance, and create cellular injury leading to local or systemic symptoms.9,14 Infection is often

described quantitatively as a bacterial count of greater

than 105 colony-forming units (CFU) per gram of tissue.9

However, some organisms such as beta-hemolytic streptococci impair wound healing at less than 105 CFU per gram

of tissue.15 According to Kravitz,16 infection should be defined as the presence of bacteria in any quantity that impairs wound healing.

Clinical signs of infection include lack of healing after

2 weeks of proper topical therapy, erythema, increase in

amount or change in character of exudate, odor, increased

local warmth, friable granulation tissue, edema or induration, pain or tenderness, fever, chills, elevated white blood

cell count, and elevated glucose in patients with diabetes.9

WON200342.indd S31

Clean vs. Sterile Dressing Techniques

S31

In patients who are immunosuppressed or have ischemic

wounds, signs of infection can be subtle. Signs of inflammation such as a faint halo of erythema and moderate

amounts of drainage might be the only signs of an infected arterial wound.17 Studies have shown that in

chronic wounds, increasing pain, friable granulation tissue, wound breakdown, and foul odor have high validity

for infection.17,18

Definition of Wounds

Wound. A wound is any break in the skin that can

vary from a superficial to a full thickness wound. A partial

thickness wound is confined to loss of the epidermis and

partial loss of the dermis; whereas a full thickness wound

has a total loss of the epidermis and dermis and can involve the deeper subcutaneous and muscle tissues and/or

bone.19,20

Acute wound. Acute wounds occur suddenly and are

commonly due to trauma or surgery, which triggers blood

clotting and a wound repair process that leads to wound

closure within 2-4 weeks.14,19

Chronic wound. A chronic wound is a one that does

not does not proceed through an orderly and timely repair

process requiring more than 4 weeks to heal such as vascular wounds and pressure wounds.14,19

Surgical wound. A surgical wound that heals in an

orderly and expected fashion may be considered an acute

wound. Surgical wounds heal by primary closure or are left

open for delayed primary closure or healing by secondary

closure. Primary closure facilitates the fastest healing.

However, infected wounds should not be primarily closed.21

Gaps in Research Practice

There is no definitive evidence that sterile technique is

superior to clean technique, improves outcomes, or is warranted when changing dressings on chronic wounds.8

Insufficient evidence is available to determine if there are

significant differences in infection rates or healing when

wounds are treated using clean or sterile technique.14

There is a lack of agreement in published expert opinion

as to what constitutes sterile versus non-sterile technique

and when one or the other should be used.

Overview of Research/Published

Expert Opinion

Few national guidelines have addressed the topic of clean

vs. sterile technique. Sterile technique and dressings have

been recommended for post-operative management of

wounds for 24-48 hours by the Centers for Disease Control

and Prevention.22 No recommendations are provided beyond 48 hours for wounds with primary closure.22,23

In 1994, clinical practice guidelines for pressure ulcer

treatment, published by the Agency for Health Care Policy

and Research, recommended use of clean gloves and clean

03/03/12 4:27 PM

S32

J WOCN

Clean vs. Sterile Dressing Techniques

dressings for pressure ulcers as long as the dressing procedures complied with the institutions policies.24 Sterile

instruments were recommended for debridement. Recent

guidelines for pressure ulcers have not addressed specifics

of clean or sterile technique other than to state that

tap water or potable water can be used to clean pressure

ulcers and that sterile instruments are needed for sharp

debridement.25

There is a paucity of research about clean vs. sterile

technique for wound care and studies have varied greatly

in their design and findings. Angeras, Brandberg, Falk, and

Seeman26 compared the use of sterile saline or tap water

for cleaning acute traumatic soft tissue wounds and found

that the infection rate in the tap water group was 5.4%

compared to 10.3% in the group using sterile saline (p .05)

with a 50% decrease in costs for the tap water group.

Two studies examined the strike through contamination in saturated sterile dressings. Alexander, Gannage,

Nichols, and Gaskins27 reported that when gauze sponges

were saturated directly in their wrapper, that contamination occurred in 100% of sponges in uncoated wrappers.

In the coated wrapped sponges, 80% exposed to

Staphylococcus epidermidis and 20% exposed to

Escherichia coli had strike through. In another study, cultures were taken from gauze sponges that were saturated

directly on their wrappers on hospital over-bed tables of

postoperative surgical patients.28 The saturated gauze

showed significant growth of microorganisms. The authors reported there was no significant difference in strikethrough contamination in gauze saturated on coated or

uncoated wrappers. Investigators in both these studies

concluded that the practice of saturating gauze sponges on

their wrappers was unacceptable.

In 1993, Stotts and colleagues conducted a descriptive,

exploratory survey of members of WOCN to obtain information regarding wound care practices in the United

States.29 Two hundred and forty-two (242) members responded to the survey. Of the respondents, 51.4% reported

use of sterile technique and 43% reported use of non-sterile technique. Sterile technique was performed more frequently in acute care than in other settings. It was also

reported that 90% of patients with open wounds being

discharged from hospitals were taught to perform nonsterile technique at home regardless of whether clean or

sterile technique was used during hospitalization.

In 1997, Stotts and colleagues compared the healing

rates and costs of sterile vs. clean technique in post-operative patients (N 30) who had wounds healing by secondary intentions following gastrointestinal surgery.30

The authors reported there was no statistically significant

difference in the rate of wound healing between the two

groups (p 0.55). The cost however was significantly

higher with sterile technique (p .05) compared with

clean technique.

Also, in 1997, Wise, Hoffman, Grant, and Bostrom surveyed staff nurses (N 723) in five health care agencies

WON200342.indd S32

March/April 2012

about the use of sterile vs. non-sterile gloves for wound

care.31 The authors reported great variations in practice and

that acute care nurses used sterile gloves for wound care

more commonly than home care nurses. In acute care, sterile gloves were used more than non-sterile for packing

wounds, in cases of purulence or tunneling, or for open

orthopedic wounds. Clean gloves were used for dressing

changes of intact surgical wounds and pressure ulcers. In

home care, non-sterile gloves were commonly used except

for open orthopedic wounds (i.e., exposed bone/tendon).

Three factors that were identified as the most influential in

glove choice were type of wound, exposed bone, and immunosuppression. Some of the other factors affecting glove

choice included type of dressing, type of drainage, time

since surgery, licensure (i.e., registered nurse vs. licensed

vocational nurse), agency policy, physician preference, and

what they were taught in school.

Lawson, Juliano, and Ratliff32 in a non-experimental,

longitudinal study monitored infection rates and supply

costs of all patients with open surgical wounds healing by

secondary intention before and 3 months after implementing non-sterile wound care. There was no statistically

significant difference in infection rates. Dressing costs and

time to perform the wound care were reduced using nonsterile dressing techniques (i.e., staff did not use sterile

gloves, scissors, or bowls).

In 2006, Fellows and Crestodina reported that the optimal cleansing agent for wound cleaning should be sterile, noncytotoxic, and inexpensive.33 Because of the cost

of sterile saline and reluctance of patients to discard unused solutions, Fellows and Crestodina conducted a small,

quasi-experimental study in a home health setting to

compare the bacterial content of home prepared saline

made with distilled water and stored at room temperature

(2 gallons) to saline stored in a refrigerator (2 gallons).

Based on cultures of the solutions immediately following

preparation and at weekly intervals for 4 weeks, the authors concluded that saline solution prepared by patients

by adding table salt to distilled water (purchased from a

grocery store) remained bacteria free for a month if refrigerated. The saline kept at room temperature had undesirable levels of bacteria after 2 weeks. The authors

recommended further studies to confirm their findings.

An integrative literature review of seven published

studies of clean and sterile technique for dressings revealed that while there is a lack of consensus about the

benefit of clean versus sterile technique to improve healing or infection rates, clean technique results in lower

costs.5

Conclusions

There is not a consensus of expert opinion on the use of

clean or sterile dressing technique in the management of

chronic wounds. Research is limited and inconclusive

about value of clean or sterile in healing outcomes. Limited

03/03/12 4:27 PM

J WOCN

Volume 39/Number 2S

S33

Clean vs. Sterile Dressing Techniques

evidence indicates clean technique reduces costs and

might require less time to perform.

Wound care is provided in a variety of patient care settings including acute care, sub-acute care, long-term care,

outpatient clinics, and in the home. The question arises:

Should a different technique be utilized in the delivery of

wound care based on the health care setting? Decisions

made about the type of technique to be used may be more

reasonably based on what will be done to the wound,

rather than where or to whom the care is delivered.1,2

Other factors that may influence the technique are the

status/acuity of the patient, the health care setting, and

type of caregiver.31 For instance, a frail, elderly patient who

is receiving immunosuppressant drugs who has a large,

full thickness, sternal wound receiving daily dressing

changes might benefit from sterile technique. A middleaged patient who was in an automobile accident and subsequently developed a non-infected, Stage III pressure

ulcer treated with hydrocolloid dressings, changed every

3-4 days, might be adequately managed using clean

technique. There is no scientific evidence or consensus

that any one of these conditions is more or less important

in selecting the appropriate method of care for the wound.

It has been suggested that an assessment of patients risk

for infection is an important factor in choosing the type

of technique.3,34

Recommendations

Recommendations for Practice: Considerations for

Clean Versus Sterile Technique

1. The following factors should be considered when

planning and selecting dressing technique for

chronic wound care.2,34

a. Patient factors, immune status, acute vs. chronic

wound.

b. Type, location, and depth of the wound.

c. Invasiveness of wound care procedure.

How invasive is the procedure?

Is debridement to be performed?

Does the procedure involve changing a simple

transparent film or hydrocolloid dressing or

extensive packing of the wound?

d. Health care setting.

Who will be doing the wound care?

What is the environment in which the care

will be delivered?

e. Selection/use of supplies/instruments.

Use and maintenance may be based on likelihood of exposure to organisms in the care setting.

What is clean, what is sterile, and what is contaminated?

Keep items apart by using no touch technique.

f. Solutions for cleansing/treatment.

Initially, solutions such as commercially prepared

wound cleansers and normal saline are sterile.

The shelf life of solutions once they are opened

is based on manufacturers recommendations

and the policy of the health care institution

providing the care. No definitive scientific evidence exists to guide the policies of the health

care institution.

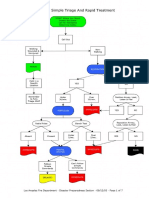

2. The Table addresses dressing technique for chronic

wounds.1,2,35

Recommendation for Education

Health care facilities should develop policies and educational programs for staff to enhance understanding and

principles of asepsis, choosing and criteria for performing

clean or sterile technique.

Recommendation for Research

Research is needed to provide an evidence-basis to support

either clean or sterile dressing technique to manage

TABLE.

Suggested Dressing Technique for the Management of Chronic Wounds

Supplies (Includes Solutions

and Dressing Supplies)

Instruments

Clean

Normal saline or commercially prepared

wound cleanser

Sterile, maintain as clean per policy*

Irrigate with sterile device;

maintain as clean per

policy*

Yes

Clean

Sterile, maintain as clean per policy*

Sterile; maintain as clean

per policy*

Dressing Change with Mechanical,

Chemical, or Enzymatic Debridement

Yes

Clean

Sterile, maintain as clean per policy*

Sterile; maintain as clean

per policy*

Dressing Change with Sharp

Conservative Bedside Debridement

Yes

Sterile

Sterile

Sterile

Intervention

Hand Washing

Gloves

Wound Cleansing

Yes

Routine Dressing Change without

Debridement

*Maintain clean per policy means that each health care setting must establish policies that address the parameters for use/maintenance of supplies/solutions,

taking into consideration such factors as expiration dates, costs, and manufacturers recommendations.

WON200342.indd S33

03/03/12 4:27 PM

S34

Clean vs. Sterile Dressing Techniques

chronic wounds. Continued research is needed that examines patient outcomes in terms of healing, infection rates,

and costs of clean vs. sterile techniques. Studies should

clearly describe methods and supplies used for clean or

sterile technique. Large multi-site, randomized studies

across health care settings are needed to insure appropriate patient outcomes are achieved in a cost effective manner that does not compromise patient safety.

References

1. APIC & WOCN. Position Statement. Clean vs. Sterile:

Management of Chronic Wounds. APIC News. 2001. http://

www.apic.org/AM/Template.cfm?SectionTopics1&CONTEN

TID6376&TEMPLATE/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm. Accessed

March 20, 2011.

2. Wooten MK, Hawkins K. APIC 2000 Guidelines Committee.

Clean versus sterile: management of chronic wounds. J Wound,

Ostomy Contin Nurs. 2001;28:24A-26A.

3. Rowley S, Clare S, Macqueen S, Molyneux R. ANTT v2: an updated practice framework for aseptic technique. Br J Nurs.

2010;19:S5S11.

4. Bates-Jensen BM, Ovington LG. Management of exudate and

infection. In: Sussman C, & Bates-Jensen B, eds. Wound Care: A

Collaborative Practice Manual for Physical Therapists and Nurses.

3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins;

2007:215-233.

5. Ferreira AM, de Andrade D. Integrative review of the clean and

sterile technique, agreement and disagreement in the execution of dressing. Acta Palulista de Enfermagem. 2008;21:117-121.

6. Aziz AM. Variations in aseptic technique and implications for

infection control. Br J Nurs. 2009;18:26-31.

7. Pegram A, Bloomfield J. Wound care: principles of aseptic technique. Ment Health Pract. 2010;14:14-18.

8. Rolstad BS, Bryant RA, Nix DP. Topical management. In:

Bryant R, & Nix D, eds. Acute & Chronic Wounds: Current management Concepts. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby;

2012:289-307.

9. Stotts NA. Wound Infection: Diagnosis and Management. In:

Bryant R, & Nix D, eds. Acute & Chronic Wounds: Current

Management Concepts. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby;

2012:270-278.

10. Sibbald RG, Woo KY, Ayello EA. Infection and inflammation.

Ostomy Wound Manag. 2009;55(Suppl):15-18.

11. Landis SJ. Chronic wound infection and antimicrobial use. Adv

Skin Wound Care. 2008;21:531-540.

12. Cowan T. Biofilms and their management: implications for the

future of wound care. J Wound Care. 2010;19:117-120.

13. Wolcott RD, Cox SB, Dowd SE. Healing and healing rates of

chronic wounds in the age of molecular pathogen diagnostics.

J Wound Care. 2010;19:272-281.

14. Gray M, Doughty D. Clean versus sterile technique when

changing wound dressings. J Wound, Ostomy Contin Nurs. 2001;

28:125-128.

15. Bowler PG. The 105 bacterial growth guideline: reassessing its

clinical relevance in wound healing. Ostomy Wound Manag.

2003;49:44-53.

16. Kravitz S. Infection: are we defining it accurately? Adv Skin

Wound Care. 2006;19:176.

17. Cutting KF, White RJ. Criteria for identifying wound infectionsRevisited. Ostomy Wound Manag. 2005;51:28-34.

WON200342.indd S34

J WOCN

March/April 2012

18. Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Doebbling BN. The validity of the

clinical signs and symptoms used to identify localized chronic

wound infection. Wound Repair Regenerat. 2001;9:178-186.

19. Doughty DB, Sparks-DeFriese B. Wound healing physiology. In:

Bryant RA, & Nix DP, eds. Acute and Chronic Wounds: Current

Management Concepts. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby-Elsevier; 2012:63-82.

20. Somerset M. ed. Wound Care Fundamentals. Wound Care Made

Incredibly Easy. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams

& Wilkins; 2007:1-26.

21. Whitney JD. Surgical wounds and incision care. In: Bryant R,

& Nix D, eds. Acute & Chronic Wounds: Current Management

Concepts. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier Mosby; 2012:469-475.

22. Mangram AJ, Horan T, Pearson ML, Silver BS, Jarvis WR.

Guideline for Prevention of Surgical Site Infection. 1999;20:247248. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. http://www.

cdc.gov/ncidod/dhqp/pdf/guidelines/SSI.pdf. Accessed

March 16, 2011.

23. Massachusetts Department of Public Health. Prevention of surgical site infections. In: Prevention and control of healthcareassociated infections in Massachusetts, 2008. http://www.

guidelines.gov/. Accessed January 29, 2011.

24. Bergstrom N, Bennett MA, Carlson C, et al. Treatment of Pressure

Ulcers. Clinical Practice Guideline No. 15:59-60. Rockville

(MD): Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Public

Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services,

AHCPR Publication No. 95-0652.; 1994.

25. NPUAP-EPUAP (National Pressure Ulcer Advisory PanelEuropean Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel). Prevention and

Treatment of Pressure Ulcers: Clinical Practice Guideline.

Washington DC: National Pressure Advisory Panel; 2009.

26. Angeras MH, Brandberg A, Falk A, Seeman T. Comparison between sterile saline and tap water for the cleaning of acute

traumatic soft tissue wounds. Eur J Surg. 1992;58:347-350.

27. Alexander D, Gammage D, Nichols A, Gaskins D. Analysis of

strike-through contamination in saturated sterile dressings.

Clin Nurs Res. 1992;1:28-34.

28. Popovich DM, Alexander D, Rittman M, Mantorella C,

Jackson L. Strike-through contamination in saturated sterile

dressings: a clinical analysis. Clin Nurs Res. 1995;4:195-207.

29. Stotts NA, Barbour S, Slaughter R, Wipke-Tevis D. Wound care

practices in the United States. Ostomy Wound Manag.

1993;39:59-62.

30. Stotts NA, Barbour S, Slaughter R, et al. Sterile versus clean

technique in postoperative wound care of patients with open

surgical wounds: a pilot study. J Wound, Ostomy Contin Nurs.

1997;24:10-8.

31. Wise LC, Hoffman J, Grant L, Bostrom J. Nursing wound care

survey: sterile and nonsterile glove choice. J Wound, Ostomy

Contin Nurs. 1997;24:144-150.

32. Lawson C, Juliano L, Ratliff C. Does sterile or nonsterile technique make a difference in wounds healing by secondary intention? Ostomy Wound Manag. 2003;49:56-8, 60.

33. Fellows J, Crestodina L. Home-prepared saline. J Wound,

Ostomy Contin Nurs. 2006;33:606-609.

34. Flores A. Sterile versus non-sterile glove use and aseptic technique. Nurs Stand. 2008;23:35-39.

35. Crow S, Thompson PJ. Infection control perspectives. In:

Krasner D, & Kane D, eds. Chronic Wound Care: A Course Book

for Healthcare Professionals. 3rd ed. Wayne, PA: Health

Management Publications; 2001:357-367.

Date Approved by the WOCN Society Board of Directors:

September 27, 2011

03/03/12 4:27 PM

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Vaksin VarelaDocument8 pagesVaksin VarelaPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- NutritionsDocument9 pagesNutritionsPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- KemoDocument11 pagesKemoPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Hominid EvolutionDocument2 pagesHominid EvolutionJosephine TorresNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Pathway ALODocument1 pagePathway ALOShila Wisnasari100% (2)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Maternitas JurnalDocument12 pagesMaternitas JurnalPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Sample WordDocument1 pageSample WordNuno AlvesNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- APARQ QuestionnaireDocument6 pagesAPARQ QuestionnairehumanismeNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Jurnal FixDocument6 pagesJurnal FixPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Jurnal FixDocument6 pagesJurnal FixPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- Acute Pulmonary Edema Algorithm: Consider ConsultationDocument1 pageAcute Pulmonary Edema Algorithm: Consider ConsultationPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Start TriageDocument7 pagesStart TriagePutra EkaNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Emergency Severity IndexDocument114 pagesEmergency Severity Indexpafin100% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Ipi 107451Document5 pagesIpi 107451Ade Churie TanjayaNo ratings yet

- 4686216Document3 pages4686216Putra EkaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- BasicDocument8 pagesBasicPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- Effectiveness of Biofeedback As A Tool To Reduce The Perception of Labour Pain Among Primigravidas: Pilot StudyDocument4 pagesEffectiveness of Biofeedback As A Tool To Reduce The Perception of Labour Pain Among Primigravidas: Pilot StudyPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- BasicDocument8 pagesBasicPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- RoleDocument8 pagesRolePutra EkaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 4686216Document3 pages4686216Putra EkaNo ratings yet

- TriageDocument6 pagesTriagePutra EkaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- BasicDocument8 pagesBasicPutra EkaNo ratings yet

- 2016 PAD ACC+AHA SlidesDocument74 pages2016 PAD ACC+AHA SlidesPonpimol Odee BongkeawNo ratings yet

- Spiritual Wrestling PDFDocument542 pagesSpiritual Wrestling PDFJames CuasmayanNo ratings yet

- Opalescence Boost Whitening PDFDocument2 pagesOpalescence Boost Whitening PDFVikas AggarwalNo ratings yet

- Genetic Recombination in Bacteria Horizon of The BDocument9 pagesGenetic Recombination in Bacteria Horizon of The BAngelo HernandezNo ratings yet

- Treatment in Dental Practice of The Patient Receiving Anticoagulation Therapy PDFDocument7 pagesTreatment in Dental Practice of The Patient Receiving Anticoagulation Therapy PDFJorge AlvaradoNo ratings yet

- Field Attachment Report FinalDocument19 pagesField Attachment Report FinalAmaaca Diva100% (5)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Understanding Cancer Treatment and OutcomesDocument5 pagesUnderstanding Cancer Treatment and OutcomesMr. questionNo ratings yet

- Cefixime and Palpitations - From FDA ReportsDocument3 pagesCefixime and Palpitations - From FDA ReportsMuhammad UbaidNo ratings yet

- 10.1055s 0039 1688815 - CompressedDocument15 pages10.1055s 0039 1688815 - CompressedYolanda Gómez LópezNo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Shock in Critical Care NursingDocument25 pagesNeurogenic Shock in Critical Care Nursingnaqib25100% (4)

- Prof. Eman Rushdy Sulphonylurea A Golden Therapy For DiabetesDocument51 pagesProf. Eman Rushdy Sulphonylurea A Golden Therapy For Diabetestorr123No ratings yet

- Abnormal Uterine Bleeding in PDFDocument25 pagesAbnormal Uterine Bleeding in PDFnelson bejarano arosemenaNo ratings yet

- Kisi2 Inggris 11Document3 pagesKisi2 Inggris 11siti RohimahNo ratings yet

- Prevod 41Document5 pagesPrevod 41JefaradocsNo ratings yet

- How Become A SurgeonDocument15 pagesHow Become A SurgeonBárbara LeiteNo ratings yet

- Feeding Sugar To Honey BeesDocument7 pagesFeeding Sugar To Honey BeesMrmohanakNo ratings yet

- CDC Org ChartDocument1 pageCDC Org Chartwelcome martinNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- What Explains The Directionality of Flow in Health Care? Patients, Health Workers and Managerial Practices?Document7 pagesWhat Explains The Directionality of Flow in Health Care? Patients, Health Workers and Managerial Practices?Dancan OnyangoNo ratings yet

- Controlling Blood Glucose 1Document2 pagesControlling Blood Glucose 1Tvisha PatelNo ratings yet

- Neurology - Anatomy Stuff UAWDocument329 pagesNeurology - Anatomy Stuff UAWNabeel Shahzad100% (1)

- Monograph On Lung Cancer July14Document48 pagesMonograph On Lung Cancer July14PatNo ratings yet

- Microbiology With Diseases by Taxonomy 6Th Edition Full ChapterDocument37 pagesMicrobiology With Diseases by Taxonomy 6Th Edition Full Chapterjoelle.yochum318100% (25)

- Family Health Survey ToolDocument7 pagesFamily Health Survey ToolReniella HidalgoNo ratings yet

- Choledo A4Document53 pagesCholedo A4Czarina ManinangNo ratings yet

- Nguyen 2019Document6 pagesNguyen 2019ClintonNo ratings yet

- Primary Health Care Hand Outs For StudentsDocument35 pagesPrimary Health Care Hand Outs For Studentsyabaeve100% (6)

- Investigation and Treatment of Surgical JaundiceDocument38 pagesInvestigation and Treatment of Surgical JaundiceUjas PatelNo ratings yet

- VECTOR BIOLOGY FOR IRS PROGRAM - Javan Chanda - 2018Document16 pagesVECTOR BIOLOGY FOR IRS PROGRAM - Javan Chanda - 2018Luo MiyandaNo ratings yet

- Immediate Dental Implant 1Document13 pagesImmediate Dental Implant 1alkhalijia dentalNo ratings yet

- Otzi ARTEFACTSDocument15 pagesOtzi ARTEFACTSBupe Bareki KulelwaNo ratings yet

- The Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossFrom EverandThe Obesity Code: Unlocking the Secrets of Weight LossRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (28)

- By the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsFrom EverandBy the Time You Read This: The Space between Cheslie's Smile and Mental Illness—Her Story in Her Own WordsNo ratings yet