Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hukka 254

Uploaded by

vrishti650 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views2 pagesDr. Sanjay gupta: laughter is part of the universal human vocabulary; we're born with it. He says most laughter doesn't follow jokes; it's about relationships between people. People laugh after a variety of statements such as "hey John, where ya been?" and "here comes mary," he says.

Original Description:

Original Title

hukka254

Copyright

© Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentDr. Sanjay gupta: laughter is part of the universal human vocabulary; we're born with it. He says most laughter doesn't follow jokes; it's about relationships between people. People laugh after a variety of statements such as "hey John, where ya been?" and "here comes mary," he says.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

18 views2 pagesHukka 254

Uploaded by

vrishti65Dr. Sanjay gupta: laughter is part of the universal human vocabulary; we're born with it. He says most laughter doesn't follow jokes; it's about relationships between people. People laugh after a variety of statements such as "hey John, where ya been?" and "here comes mary," he says.

Copyright:

Attribution Non-Commercial (BY-NC)

Available Formats

Download as RTF, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

May 27, 1999 - Laughter is part of the universal human vocabulary.

All members of the

human species understand it. Unlike English or French or Swahili, we don’t have to learn

to speak it. We’re born with the capacity to laugh.

One of the remarkable things about laughter is that it occurs unconsciously. You don’t

decide to do it. While we can consciously inhibit it, we don’t consciously produce

laughter. That’s why it’s very hard to laugh on command or to fake laughter. (Don’t take

my word for it: Ask a friend to laugh on the spot.)

Laughter provides powerful, uncensored insights into our unconscious. It simply bubbles

up from within us in certain situations.

Very little is known about the specific brain mechanisms responsible for laughter. But we

do know that laughter is triggered by many sensations and thoughts, and that it activates

many parts of the body.

When we laugh, we alter our facial expressions and make sounds. During exuberant

laughter, the muscles of the arms, legs and trunk are involved. Laughter also requires

modification in our pattern of breathing.

We also know that laughter is a message that we send to other people. We know this

because we rarely laugh when we are alone (we laugh to ourselves even less than we talk

to ourselves).

Laughter is social and contagious. We laugh at the sound of laughter itself. That’s why

the Tickle Me Elmo doll is such a success — it makes us laugh and smile.

The first laughter appears at about 3.5 to 4 months of age, long before we’re able to

speak. Laughter, like crying, is a way for a preverbal infant to interact with the mother

and other caregivers.

Contrary to folk wisdom, most laughter is not about humor; it is about relationships

between people. To find out when and why people laugh, I and several undergraduate

research assistants went to local malls and city sidewalks and recorded what happened

just before people laughed. Over a 10-year period, we studied over 2,000 cases of

naturally occurring laughter.

We found that most laughter does not follow jokes. People laugh after a variety of

statements such as “Hey John, where ya been?” “Here comes Mary,” “How did you do

on the test?” and “Do you have a rubber band?”. These certainly aren’t jokes.

We don’t decide to laugh at these moments. Our brain makes the decision for us. These

curious “ha ha ha’s” are bits of social glue that bond relationships.

Curiously, laughter seldom interrupts the sentence structure of speech. It punctuates

speech. We only laugh during pauses when we would cough or breathe.

An evolutionary perspective

We believe laughter evolved from the panting behavior of our ancient primate ancestors.

Today, if we tickle chimps or gorillas, they don’t laugh “ha ha ha” but exhibit a panting

sound. That’s the sound of ape laughter. And it’s the root of human laughter.

Apes laugh in conditions in which human laughter is produced, like tickle, rough and

tumble play, and chasing games. Other animals produce vocalizations during play, but

they are so different that it’s difficult to equate them with laughter. Rats, for example,

produce high-pitch vocalizations during play and when tickled. But it’s very different in

sound from human laughter.

When we laugh, we’re often communicating playful intent. So laughter has a bonding

function within individuals in a group. It’s often positive, but it can be negative too.

There’s a difference between “laughing with” and “laughing at.” People who laugh at

others may be trying to force them to conform or casting them out of the group.

No one has actually counted how much people of different ages laugh, but young

children probably laugh the most. At ages 5 and 6, we tend to see the most exuberant

laughs. Adults laugh less than children, probably because they play less. And laughter is

associated with play.

We have learned a lot about when and why we laugh, much of it counter-intuitive. Work

now underway will tell us more about the brain mechanisms of laughter, how laughter

has evolved and why we’re so susceptible to tickling — one of the most enigmatic of

human behaviors.

Robert Provine, Ph.D., is a professor of psychology and neuroscience at the University of

Maryland, Baltimore County. He is completing a book entitled “Laughter” that is

scheduled to be published this fall by Little, Brown and Company.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Christian Borch & Gernot Bohme & Olafur Eliasson & Juhani Pallasmaa - Architectural Atmospheres-BirkhauserDocument112 pagesChristian Borch & Gernot Bohme & Olafur Eliasson & Juhani Pallasmaa - Architectural Atmospheres-BirkhauserAja100% (1)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Fig. 6.14 Circular WaveguideDocument16 pagesFig. 6.14 Circular WaveguideThiagu RajivNo ratings yet

- Attachment 1 - Memorandum Order No. 21-1095 - Revised Guidelines For The Implementation of Shared Service Facilities (SSF) ProjectDocument28 pagesAttachment 1 - Memorandum Order No. 21-1095 - Revised Guidelines For The Implementation of Shared Service Facilities (SSF) ProjectMark Jurilla100% (1)

- Estudio - Women Who Suffered Emotionally From Abortion - A Qualitative Synthesis of Their ExperiencesDocument6 pagesEstudio - Women Who Suffered Emotionally From Abortion - A Qualitative Synthesis of Their ExperiencesSharmely CárdenasNo ratings yet

- Yeb2019 Template MhayDocument9 pagesYeb2019 Template MhayloretaNo ratings yet

- Course Welcome and Overview ACADocument20 pagesCourse Welcome and Overview ACAAlmerNo ratings yet

- ARCODE UCM Test Instructions V13.EnDocument4 pagesARCODE UCM Test Instructions V13.EnHenri KleineNo ratings yet

- Kanne Gerber Et Al Vineland 2010Document12 pagesKanne Gerber Et Al Vineland 2010Gh8jfyjnNo ratings yet

- PSCI101 - Prelims ReviewerDocument3 pagesPSCI101 - Prelims RevieweremmanuelcambaNo ratings yet

- MEM Companion Volume Implementation Guide - Release 1.1Document23 pagesMEM Companion Volume Implementation Guide - Release 1.1Stanley AlexNo ratings yet

- Assignment # (02) : Abasyn University Peshawar Department of Computer ScienceDocument4 pagesAssignment # (02) : Abasyn University Peshawar Department of Computer ScienceAndroid 360No ratings yet

- Homa Pump Catalog 2011Document1,089 pagesHoma Pump Catalog 2011themejia87No ratings yet

- Whether To Use Their GPS To Find Their Way To The New Cool Teen HangoutDocument3 pagesWhether To Use Their GPS To Find Their Way To The New Cool Teen HangoutCarpovici Victor100% (1)

- Biological Activity of Bone Morphogenetic ProteinsDocument4 pagesBiological Activity of Bone Morphogenetic Proteinsvanessa_werbickyNo ratings yet

- NYC Ll11 Cycle 9 FinalDocument2 pagesNYC Ll11 Cycle 9 FinalKevin ParkerNo ratings yet

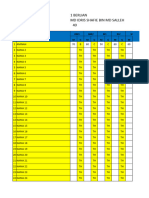

- TEMPLATE Keputusan Peperiksaan THP 1Document49 pagesTEMPLATE Keputusan Peperiksaan THP 1SABERI BIN BANDU KPM-GuruNo ratings yet

- Flex Li3 21 VAADocument1 pageFlex Li3 21 VAAAyman Al-YafeaiNo ratings yet

- Designation of Mam EdenDocument2 pagesDesignation of Mam EdenNHASSER PASANDALANNo ratings yet

- Full Download Book The Genus Citrus PDFDocument41 pagesFull Download Book The Genus Citrus PDFwilliam.rose150100% (14)

- Commercial Dispatch Eedition 6-13-19Document12 pagesCommercial Dispatch Eedition 6-13-19The Dispatch100% (1)

- Material Safety Data Sheet Visco WelDocument4 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet Visco Welfs1640No ratings yet

- 1, Philippine ConstitutionDocument2 pages1, Philippine ConstitutionJasmin KumarNo ratings yet

- Closing Ceremony PresentationDocument79 pagesClosing Ceremony Presentationapi-335718710No ratings yet

- El Poder de La Disciplina El Hábito Que Cambiará Tu Vida (Raimon Samsó)Document4 pagesEl Poder de La Disciplina El Hábito Que Cambiará Tu Vida (Raimon Samsó)ER CaballeroNo ratings yet

- CVT / TCM Calibration Data "Write" Procedure: Applied VehiclesDocument20 pagesCVT / TCM Calibration Data "Write" Procedure: Applied VehiclesАндрей ЛозовойNo ratings yet

- Policy ScheduleDocument1 pagePolicy ScheduleDinesh nawaleNo ratings yet

- PGY2 SummaryDocument3 pagesPGY2 SummarySean GreenNo ratings yet

- Finals Lesson Ii Technology As A WAY of Revealing: Submitted By: Teejay M. AndrdaDocument8 pagesFinals Lesson Ii Technology As A WAY of Revealing: Submitted By: Teejay M. AndrdaTeejay AndradaNo ratings yet

- 13 Reasons Why Discussion GuideDocument115 pages13 Reasons Why Discussion GuideEC Pisano RiggioNo ratings yet

- Walsh January Arrest Sherrif Records Pgs 10601-10700Document99 pagesWalsh January Arrest Sherrif Records Pgs 10601-10700columbinefamilyrequest100% (1)