Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AMLC vs. Eugenio - Bank inquiry orders assailed

Uploaded by

Jacinto Jr JameroOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AMLC vs. Eugenio - Bank inquiry orders assailed

Uploaded by

Jacinto Jr JameroCopyright:

Available Formats

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

G.R.No.174629February14,2008

REPUBLICOFTHEPHILIPPINES,RepresentedbyTHEANTIMONEYLAUNDERINGCOUNCIL

(AMLC),petitioner,

vs.

HON.ANTONIOM.EUGENIO,JR.,ASPRESIDINGJUDGEOFRTC,MANILA,BRANCH34,

PANTALEONALVAREZandLILIACHENG,respondents.

DECISION

TINGA,J.:

ThepresentpetitionforcertiorariandprohibitionunderRule65assailstheordersandresolutionsissued

bytwodifferentcourtsintwodifferentcases.ThecourtsandcasesinquestionaretheRegionalTrialCourt

of Manila, Branch 24, which heard SP Case No. 061142001 and the Court of Appeals, Tenth Division,

whichhearedCAG.R.SPNo.95198.2BothcasesaroseaspartoftheaftermathoftherulingofthisCourt

in Agan v. PIATCO3nullifying the concession agreement awarded to the Philippine International Airport

Terminal Corporation (PIATCO) over the Ninoy Aquino International Airport International Passenger

Terminal3(NAIA3)Project.

I.

Following the promulgation of Agan, a series of investigations concerning the award of the NAIA 3

contracts to PIATCO were undertaken by the Ombudsman and the Compliance and Investigation Staff

(CIS) of petitioner AntiMoney Laundering Council (AMLC). On 24 May 2005, the Office of the Solicitor

General (OSG) wrote the AMLC requesting the latters assistance "in obtaining more evidence to

completely reveal the financial trail of corruption surrounding the [NAIA 3] Project," and also noting that

petitioner Republic of the Philippines was presently defending itself in two international arbitration cases

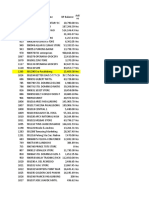

filedinrelationtotheNAIA3Project.4TheCISconductedanintelligencedatabasesearchonthefinancial

transactionsofcertainindividualsinvolvedintheaward,includingrespondentPantaleonAlvarez(Alvarez)

whohadbeentheChairmanofthePBACTechnicalCommittee,NAIAIPT3Project.5Bythistime,Alvarez

hadalreadybeenchargedbytheOmbudsmanwithviolationofSection3(j)ofR.A.No.3019.6Thesearch

revealedthatAlvarezmaintainedeight(8)bankaccountswithsix(6)differentbanks.7

On27June2005,theAMLCissuedResolutionNo.75,Seriesof2005,8wherebytheCouncilresolvedto

authorize the Executive Director of the AMLC "to sign and verify an application to inquire into and/or

examine the [deposits] or investments of Pantaleon Alvarez, Wilfredo Trinidad, Alfredo Liongson, and

ChengYong,andtheirrelatedwebofaccountswhereverthesemaybefound,asdefinedunderRule10.4

oftheRevisedImplementingRulesandRegulations"andtoauthorizetheAMLCSecretariat"toconduct

aninquiryintosubjectaccountsoncetheRegionalTrialCourtgrantstheapplicationtoinquireintoand/or

examine the bank accounts" of those four individuals.9 The resolution enumerated the particular bank

accounts of Alvarez, Wilfredo Trinidad (Trinidad), Alfredo Liongson (Liongson) and Cheng Yong which

were to be the subject of the inquiry.10 The rationale for the said resolution was founded on the cited

findings of the CIS that amounts were transferred from a Hong Kong bank account owned by Jetstream

PacificLtd.AccounttobankaccountsinthePhilippinesmaintainedbyLiongsonandChengYong.11 The

Resolution also noted that "[b]y awarding the contract to PIATCO despite its lack of financial capacity,

Pantaleon Alvarez caused undue injury to the government by giving PIATCO unwarranted benefits,

advantage,orpreferenceinthedischargeofhisofficialadministrativefunctionsthroughmanifestpartiality,

evidentbadfaith,orgrossinexcusablenegligence,inviolationofSection3(e)ofRepublicActNo.3019."12

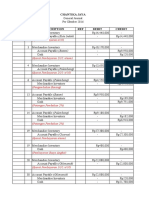

UndertheauthoritygrantedbytheResolution,theAMLCfiledanapplicationtoinquireintoorexaminethe

depositsorinvestmentsofAlvarez,Trinidad,LiongsonandChengYongbeforetheRTCofMakati,Branch

138,presidedbyJudge(nowCourtofAppealsJustice)SixtoMarella,Jr.Theapplicationwasdocketedas

AMLC No. 05005.13The Makati RTC heard the testimony of the Deputy Director of the AMLC, Richard

DavidC.FunkII,andreceivedthedocumentaryevidenceoftheAMLC.14Thereafter,on4July2005,the

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

1/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

MakatiRTCrenderedanOrder(MakatiRTCbankinquiryorder)grantingtheAMLCtheauthoritytoinquire

and examine the subject bank accounts of Alvarez, Trinidad, Liongson and Cheng Yong, the trial court

beingsatisfiedthatthereexisted"[p]robablecause[to]believethatthedepositsinvariousbankaccounts,

detailsofwhichappearinparagraph1oftheApplication,arerelatedtotheoffenseofviolationofAntiGraft

andCorruptPracticesActnowthesubjectofcriminalprosecutionbeforetheSandiganbayanasattestedto

bytheInformations,ExhibitsC,D,E,F,andG."15PursuanttotheMakatiRTCbankinquiryorder,theCIS

proceededtoinquireandexaminethedeposits,investmentsandrelatedwebaccountsofthefour.16

Meanwhile, the Special Prosecutor of the Office of the Ombudsman, Dennis VillaIgnacio, wrote a letter

dated 2 November 2005, requesting the AMLC to investigate the accounts of Alvarez, PIATCO, and

severalotherentitiesinvolvedinthenullifiedcontract.Theletteradvertedtoprobablecausetobelievethat

thebankaccounts"wereusedinthecommissionofunlawfulactivitiesthatwerecommitted"inrelationto

thecriminalcasesthenpendingbeforetheSandiganbayan.17Attachedtotheletterwasamemorandum

"on why the investigation of the [accounts] is necessary in the prosecution of the above criminal cases

beforetheSandiganbayan."18

In response to the letter of the Special Prosecutor, the AMLC promulgated on 9 December 2005

ResolutionNo.121Seriesof2005,19whichauthorizedtheexecutivedirectoroftheAMLCtoinquireinto

andexaminetheaccountsnamedintheletter,includingonemaintainedbyAlvarezwithDBSBankandtwo

other accounts in the name of Cheng Yong with Metrobank. The Resolution characterized the

memorandum attached to the Special Prosecutors letter as "extensively justif[ying] the existence of

probablecausethatthebankaccountsofthepersonsandentitiesmentionedintheletterarerelatedtothe

unlawfulactivityofviolationofSections3(g)and3(e)ofRep.ActNo.3019,asamended."20

Following the December 2005 AMLC Resolution, the Republic, through the AMLC, filed an

application21 before the Manila RTC to inquire into and/or examine thirteen (13) accounts and two (2)

relatedwebofaccountsallegedashavingbeenusedtofacilitatecorruptionintheNAIA3Project.Among

said accounts were the DBS Bank account of Alvarez and the Metrobank accounts of Cheng Yong. The

case was raffled to Manila RTC, Branch 24, presided by respondent Judge Antonio Eugenio, Jr., and

docketedasSPCaseNo.06114200.

On 12 January 2006, the Manila RTC issued an Order (Manila RTC bank inquiry order) granting the Ex

ParteApplication expressing therein "[that] the allegations in said application to be impressed with merit,

and in conformity with Section 11 of R.A. No. 9160, as amended, otherwise known as the AntiMoney

Laundering Act (AMLA) of 2001 and Rules 11.1 and 11.2 of the Revised Implementing Rules and

Regulations."22AuthoritywasthusgrantedtotheAMLCtoinquireintothebankaccountslistedtherein.

On 25 January 2006, Alvarez, through counsel, entered his appearance23before the Manila RTC in SP

Case No. 06114200 and filed an Urgent Motion to Stay Enforcement of Order of January 12,

2006.24Alvarezallegedthathefortuitouslylearnedofthebankinquiryorder,whichwasissuedfollowing

anexparteapplication, and he argued that nothing in R.A. No. 9160 authorized the AMLC to seek the

authoritytoinquireintobankaccountsexparte.25ThedayafterAlvarezfiledhismotion,26January2006,

the Manila RTC issued an Order26 staying the enforcement of its bank inquiry order and giving the

Republicfive(5)daystorespondtoAlvarezsmotion.

The Republic filed an Omnibus Motion for Reconsideration27of the 26 January 2006 Manila RTC Order

and likewise sought to strike out Alvarezs motion that led to the issuance of said order. For his part,

AlvarezfiledaReplyandMotiontoDismiss28theapplicationforbankinquiryorder.On2May2006,the

Manila RTC issued an Omnibus Order29 granting the Republics Motion for Reconsideration, denying

Alvarezs motion to dismiss and reinstating "in full force and effect" the Order dated 12 January 2006. In

the omnibus order, the Manila RTC reiterated that the material allegations in the application for bank

inquiry order filed by the Republic stood as "the probable cause for the investigation and examination of

thebankaccountsandinvestmentsoftherespondents."30

Alvarez filed on 10 May 2006 an Urgent Motion31 expressing his apprehension that the AMLC would

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

2/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

immediately enforce the omnibus order and would thereby render the motion for reconsideration he

intended to file as moot and academic thus he sought that the Republic be refrained from enforcing the

omnibus order in the meantime. Acting on this motion, the Manila RTC, on 11 May 2006, issued an

Order32 requiring the OSG to file a comment/opposition and reminding the parties that judgments and

ordersbecomefinalandexecutoryupontheexpirationoffifteen(15)daysfromreceiptthereof,asitisthe

period within which a motion for reconsideration could be filed. Alvarez filed his Motion for

Reconsideration33oftheomnibusorderon15May2006,butthemotionwasdeniedbytheManilaRTCin

anOrder34dated5July2006.

On 11 July 2006, Alvarez filed an Urgent Motion and Manifestation35 wherein he manifested having

received reliable information that the AMLC was about to implement the Manila RTC bank inquiry order

eventhoughhewasintendingtoappealfromit.Onthepremisethatonlyafinalandexecutoryjudgmentor

ordercouldbeexecutedorimplemented,AlvarezsoughtthattheAMLCbeimmediatelyorderedtorefrain

fromenforcingtheManilaRTCbankinquiryorder.

On12July2006,theManilaRTC,actingonAlvarezslatestmotion,issuedanOrder36directingtheAMLC

"to refrain from enforcing the order dated January 12, 2006 until the expiration of the period to appeal,

withoutanyappealhavingbeenfiled."Onthesameday,AlvarezfiledaNoticeofAppeal37withtheManila

RTC.

On 24 July 2006, Alvarez filed an UrgentExParteMotion for Clarification.38 Therein, he alleged having

learnedthattheAMLChadbegantoinquireintothebankaccountsoftheotherpersonsmentionedinthe

application for bank inquiry order filed by the Republic.39Considering that the Manila RTC bank inquiry

order was issued ex parte, without notice to those other persons, Alvarez prayed that the AMLC be

ordered to refrain from inquiring into any of the other bank deposits and alleged web of accounts

enumerated in AMLCs application with the RTC and that the AMLC be directed to refrain from using,

disclosing or publishing in any proceeding or venue any information or document obtained in violation of

the11May2006RTCOrder.40

On25July2006,oronedayafterAlvarezfiledhismotion,theManilaRTCissuedanOrder41wherein it

clarifiedthat"theExParteOrderofthisCourtdatedJanuary12,2006cannotbeimplementedagainstthe

depositsoraccountsofanyofthepersonsenumeratedintheAMLCApplicationuntiltheappealofmovant

Alvarez is finally resolved, otherwise, the appeal would be rendered moot and academic or even

nugatory."42In addition, the AMLC was ordered "not to disclose or publish any information or document

foundorobtainedin[v]iolationoftheMay11,2006OrderofthisCourt."43TheManilaRTCreasonedthat

the other persons mentioned in AMLCs application were not served with the courts 12 January 2006

Order. This 25 July 2006 Manila RTC Order is the first of the four rulings being assailed through this

petition.

In response, the Republic filed an Urgent Omnibus Motion for Reconsideration44 dated 27 July 2006,

urgingthatitbeallowedtoimmediatelyenforcethebankinquiryorderagainstAlvarezandthatAlvarezs

noticeofappealbeexpungedfromtherecordssinceappealfromanorderofinquiryisdisallowedunder

theAntimoneyLaunderingAct(AMLA).

Meanwhile,respondentLiliaChengfiledwiththeCourtofAppealsaPetitionforCertiorari,Prohibitionand

Mandamus with Application for TRO and/or Writ of Preliminary Injunction45dated 10 July 2006, directed

againsttheRepublicofthePhilippinesthroughtheAMLC,ManilaRTCJudgeEugenio,Jr.andMakatiRTC

Judge Marella, Jr.. She identified herself as the wife of Cheng Yong46 with whom she jointly owns a

conjugal bank account with Citibank that is covered by the Makati RTC bank inquiry order, and two

conjugal bank accounts with Metrobank that are covered by the Manila RTC bank inquiry order. Lilia

ChengimputedgraveabuseofdiscretiononthepartoftheMakatiandManilaRTCsingrantingAMLCsex

parteapplicationsforabankinquiryorder,arguingamongothersthattheexparteapplicationsviolatedher

constitutional right to due process, that the bank inquiry order under the AMLA can only be granted in

connection with violations of the AMLA and that the AMLA can not apply to bank accounts opened and

transactions entered into prior to the effectivity of the AMLA or to bank accounts located outside the

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

3/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

Philippines.47

On1August2006,theCourtofAppeals,actingonLiliaChengspetition,issuedaTemporaryRestraining

Order48enjoining the Manila and Makati trial courts from implementing, enforcing or executing the

respective bank inquiry orders previously issued, and the AMLC from enforcing and implementing such

orders.Onevendate,theManilaRTCissuedanOrder49resolvingtoholdinabeyancetheresolutionof

the urgent omnibus motion for reconsideration then pending before it until the resolution of Lilia Chengs

petitionforcertiorariwiththeCourtofAppeals.TheCourtofAppealsResolutiondirectingtheissuanceof

thetemporaryrestrainingorderisthesecondofthefourrulingsassailedinthepresentpetition.

Thethirdassailedruling50wasissuedon15August2006bytheManilaRTC,actingontheUrgentMotion

forClarification51dated 14 August 2006 filed by Alvarez. It appears that the 1 August 2006 Manila RTC

Orderhadamendeditsprevious25July2006Orderbydeletingthelastparagraphwhichstatedthatthe

AMLC "should not disclose or publish any information or document found or obtained in violation of the

May11,2006OrderofthisCourt."52Inthisnewmotion,Alvarezarguedthatthedeletionofthatparagraph

would allow the AMLC to implement the bank inquiry orders and publish whatever information it might

obtainthereuponevenbeforethefinalordersoftheManilaRTCcouldbecomefinalandexecutory.53 In

the15August2006Order,theManilaRTCreiteratedthatthebankinquiryorderithadissuedcouldnotbe

implementedorenforcedbytheAMLCoranyofitsrepresentativesuntiltheappealtherefromwasfinally

resolvedandthatanyenforcementthereofwouldbeunauthorized.54

The present Consolidated Petition55 for certiorari and prohibition under Rule 65 was filed on 2 October

2006,assailingthetwoOrdersoftheManilaRTCdated25Julyand15August2006andtheTemporary

Restraining Order dated 1 August 2006 of the Court of Appeals. Through an Urgent Manifestation and

Motion56dated 9 October 2006, petitioner informed the Court that on 22 September 2006, the Court of

Appeals hearing Lilia Chengs petition had granted a writ of preliminary injunction in her

favor.57Thereafter,petitionersoughtaswellthenullificationofthe22September2006Resolutionofthe

CourtofAppeals,therebyconstitutingthefourthrulingassailedintheinstantpetition.58

The Court had initially granted a Temporary Restraining Order59 dated 6 October 2006 and later on a

Supplemental Temporary Restraining Order60dated 13 October 2006 in petitioners favor, enjoining the

implementation of the assailed rulings of the Manila RTC and the Court of Appeals. However, on

respondents motion, the Court, through a Resolution61 dated 11 December 2006, suspended the

implementationoftherestrainingordersithadearlierissued.

Oralargumentswereheldon17January2007.TheCourtconsolidatedtheissuesforargumentasfollows:

1.DidtheRTCManila,inissuingtheOrdersdated25July2006and15August2006whichdeferred

the implementation of its Order dated 12 January 2006, and the Court of Appeals, in issuing its

Resolutiondated1August2006,whichorderedthestatusquoinrelationtothe1July2005Orderof

the RTCMakati and the 12 January 2006 Order of the RTCManila, both of which authorized the

examinationofbankaccountsunderSection11ofRep.ActNo.9160(AMLA),commitgraveabuse

ofdiscretion?

(a)Isanapplicationforanorderauthorizinginquiryintoorexaminationofbankaccountsor

investments under Section 11 of the AMLA exparte in nature or one which requires notice

andhearing?

(b) What legal procedures and standards should be observed in the conduct of the

proceedingsfortheissuanceofsaidorder?

(c)Issuchordersusceptibletolegalchallengesandjudicialreview?

2.IsitproperforthisCourtatthistimeandinthiscasetoinquireintoandpassuponthevalidityof

the 1 July 2005 Order of the RTCMakati and the 12 January 2006 Order of the RTCManila,

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

4/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

consideringthependencyofCAG.R.SPNo.95198(LiliaChengv.Republic)whereinthevalidityof

bothorderswaschallenged?62

After the oral arguments, the parties were directed to file their respective memoranda, which they

did,63andthepetitionwasthereafterdeemedsubmittedforresolution.

II.

Petitioners general advocacy is that the bank inquiry orders issued by the Manila and Makati RTCs are

validandimmediatelyenforceablewhereastheassailedrulings,whicheffectivelystayedtheenforcement

of the Manila and Makati RTCs bank inquiry orders, are sullied with grave abuse of discretion. These

conclusionsflowfromtheposturethatabankinquiryorder,issueduponafindingofprobablecause,may

be issued ex parte and, once issued, is immediately executory. Petitioner further argues that the

informationobtainedfollowingthebankinquiryisnecessarilybeneficial,ifnotindispensable,totheAMLC

indischargingitsawesomeresponsibilityregardingtheeffectiveimplementationoftheAMLAandthatany

restraint in the disclosure of such information to appropriate agencies or other judicial fora would render

meaninglessthereliefsuppliedbythebankinquiryorder.

Petitioner raises particular arguments questioning Lilia Chengs right to seek injunctive relief before the

Court of Appeals, noting that not one of the bank inquiry orders is directed against her. Her "cryptic

assertion" that she is the wife of Cheng Yong cannot, according to petitioner, "metamorphose into the

requisite legal standing to seek redress for an imagined injury or to maintain an action in behalf of

another." In the same breath, petitioner argues that Alvarez cannot assert any violation of the right to

financialprivacyinbehalfofotherpersonswhosebankaccountsarebeinginquiredinto,particularlythose

other persons named in the Makati RTC bank inquiry order who did not take any step to oppose such

ordersbeforethecourts.

Ostensibly,theproximatequestionbeforetheCourtiswhetherabankinquiryorderissuedinaccordance

withSection10oftheAMLAmaybestayedbyinjunction.Yetinarguingthatitdoes,petitionerrelieson

what it posits as the final and immediately executory character of the bank inquiry orders issued by the

Manila and Makati RTCs. Implicit in that position is the notion that the inquiry orders are valid, and such

notion is susceptible to review and validation based on what appears on the face of the orders and the

applicationswhichtriggeredtheirissuance,aswellastheprovisionsoftheAMLAgoverningtheissuance

ofsuchorders.Indeed,totesttheviabilityofpetitionersargument,theCourtwillhavetobesatisfiedthat

the subject inquiry orders are valid in the first place. However, even from a cursory examination of the

applicationsforinquiryorderandtheordersthemselves,itisevidentthattheordersarenotinaccordance

withlaw.

III.

AbriefoverviewoftheAMLAiscalledfor.

Money laundering has been generally defined by the International Criminal Police Organization (Interpol)

`as"anyactorattemptedacttoconcealordisguisetheidentityofillegallyobtainedproceedssothatthey

appeartohaveoriginatedfromlegitimatesources."64EvenbeforethepassageoftheAMLA,theproblem

was addressed by the Philippine government through the issuance of various circulars by the Bangko

Sentral ng Pilipinas. Yet ultimately, legislative proscription was necessary, especially with the inclusion of

thePhilippinesintheFinancialActionTaskForceslistofnoncooperativecountriesandterritoriesinthe

fightagainstmoneylaundering.65TheoriginalAMLA,RepublicAct(R.A.)No.9160,waspassedin2001.It

wasamendedbyR.A.No.9194in2003.

Section 4 of the AMLA states that "[m]oney laundering is a crime whereby the proceeds of an unlawful

activity as [defined in the law] are transacted, thereby making them appear to have originated from

legitimate sources."66The section further provides the three modes through which the crime of money

launderingiscommitted.Section7createstheAMLCanddefinesitspowers,whichgenerallyrelatetothe

enforcementoftheAMLAprovisionsandtheinitiationoflegalactionsauthorizedintheAMLAsuchascivil

forefeitureproceedingsandcomplaintsfortheprosecutionofmoneylaunderingoffenses.67

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

5/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

Inadditiontoprovidingforthedefinitionandpenaltiesforthecrimeofmoneylaundering,theAMLAalso

authorizescertainprovisionalremediesthatwouldaidtheAMLCintheenforcementoftheAMLA.These

arethe"freezeorder"authorizedunderSection10,andthe"bankinquiryorder"authorizedunderSection

11.

Respondents posit that a bank inquiry order under Section 11 may be obtained only upon the pre

existenceofamoneylaunderingoffensecasealreadyfiledbeforethecourts.68The conclusion is based

on the phrase "upon order of any competent court in cases of violation of this Act," the word "cases"

generallyunderstoodasreferringtoactualcasespendingwiththecourts.

Weareunconvincedbythisproposition,andagreeinsteadwiththethenSolicitorGeneralwhoconceded

that the use of the phrase "in cases of" was unfortunate, yet submitted that it should be interpreted to

mean"intheeventthereareviolations"oftheAMLA,andnotthattherearealreadycasespendingincourt

concerning such violations.69 If the contrary position is adopted, then the bank inquiry order would be

limited in purpose as a tool in aid of litigation of live cases, and wholly inutile as a means for the

government to ascertain whether there is sufficient evidence to sustain an intended prosecution of the

accountholderforviolationoftheAMLA.Shouldthatbethesituation,inalllikelihoodtheAMLCwouldbe

virtually deprived of its character as a discovery tool, and thus would become less circumspect in filing

complaintsagainstsuspectaccountholders.Afterall,undersuchsetupthepreferredstrategywouldbeto

allow or even encourage the indiscriminate filing of complaints under the AMLA with the hope or

expectation that the evidence of money laundering would somehow surface during the trial. Since the

AMLC could not make use of the bank inquiry order to determine whether there is evidentiary basis to

prosecute the suspected malefactors, not filing any case at all would not be an alternative. Such

unwholesomesetupshouldnotcometopass.ThusSection11cannotbeinterpretedinawaythatwould

emasculatetheremedyithasestablishedandencouragetheunfoundedinitiationofcomplaintsformoney

laundering.

Still,evenifthebankinquiryordermaybeavailedofwithoutneedofapreexistingcaseundertheAMLA,

it does not follow that such order may be availed ofexparte.There are several reasons why the AMLA

doesnotgenerallysanctionexparteapplicationsandissuancesofthebankinquiryorder.

IV.

ItisevidentthatSection11doesnotspecificallyauthorize,asageneralrule,theissuanceexparteofthe

bankinquiryorder.Wequotetheprovisioninfull:

SEC.11.AuthoritytoInquireintoBankDeposits. Notwithstanding the provisions of Republic Act

No.1405,asamended,RepublicActNo.6426,asamended,RepublicActNo.8791,andotherlaws,theAMLC

may inquire into or examine any particular deposit or investment with any banking institution or non bank

financial institution upon order of any competent court in cases of violation of this Act, when it has been

established that there is probable cause that the deposits or investments are related to an unlawful

activity as defined in Section 3(i) hereof or a money laundering offense under Section 4 hereof, except

that no court order shall be required in cases involving unlawful activities defined in Sections 3(i)1, (2)

and(12).

To ensure compliance with this Act, the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) may inquire into or

examineanydepositofinvestmentwithanybankinginstitutionornonbankfinancialinstitutionwhen

theexaminationismadeinthecourseofaperiodicorspecialexamination,inaccordancewiththe

rulesofexaminationoftheBSP.70(Emphasissupplied)

Ofcourse,Section11alsoallowstheAMLCtoinquireintobankaccountswithouthavingtoobtainajudicial

orderincaseswherethereisprobablecausethatthedepositsorinvestmentsarerelatedtokidnappingfor

ransom,71certain violations of the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002,72 hijacking and other

violations under R.A. No. 6235, destructive arson and murder. Since such special circumstances do not

applyinthiscase,thereisnoneedforustopasscommentonthisproviso.Sufficeittosay,theproviso

contemplates a situation distinct from that which presently confronts us, and for purposes of the

succeedingdiscussion,ourreferencetoSection11oftheAMLAexcludessaidproviso.

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

6/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

In the instances where a court order is required for the issuance of the bank inquiry order, nothing in

Section11specificallyauthorizesthatsuchcourtordermaybeissuedexparte.Itmightbearguedthatthis

silencedoesnotprecludetheexparteissuanceofthebankinquiryordersincethesameisnotprohibited

under Section 11. Yet this argument falls when the immediately preceding provision, Section 10, is

examined.

SEC.10.FreezingofMonetaryInstrumentorProperty.TheCourtofAppeals,uponapplicationex

partebytheAMLCandafterdeterminationthatprobablecauseexiststhatanymonetaryinstrumentorproperty

isinanywayrelatedtoanunlawfulactivityasdefinedinSection3(i)hereof,mayissueafreeze order which

shallbeeffectiveimmediately.Thefreezeordershallbeforaperiodoftwenty(20)daysunlessextendedby

thecourt. 73

Although oriented towards different purposes, the freeze order under Section 10 and the bank inquiry

order under Section 11 are similar in that they are extraordinary provisional reliefs which the AMLC may

availoftoeffectivelycombatandprosecutemoneylaunderingoffenses.Crucially,Section10usesspecific

language to authorize anex parte application for the provisional relief therein, a circumstance absent in

Section11.Ifindeedthelegislaturehadintendedtoauthorizeexparteproceedingsfortheissuanceofthe

bankinquiryorder,thenitcouldhaveeasilyexpressedsuchintentinthelaw,asitdidwiththefreezeorder

underSection10.

Evenmoretellingly,thecurrentlanguageofSections10and11oftheAMLAwascraftedatthesametime,

through the passage of R.A. No. 9194. Prior to the amendatory law, it was the AMLC, not the Court of

Appeals,whichhadauthoritytoissueafreezeorder,whereasabankinquiryorderalwaysthenrequired,

without exception, an order from a competent court.74 It was through the same enactment that ex

parteproceedingswereintroducedforthefirsttimeintotheAMLA,inthecaseofthefreezeorderwhich

now can only be issued by the Court of Appeals. It certainly would have been convenient, through the

same amendatory law, to allow a similar ex parte procedure in the case of a bank inquiry order had

Congress been so minded. Yet nothing in the provision itself, or even the available legislative record,

explicitly points to anexpartejudicial procedure in the application for a bank inquiry order, unlike in the

caseofthefreezeorder.

That the AMLA does not contemplate ex parte proceedings in applications for bank inquiry orders is

confirmedbythepresentimplementingrulesandregulationsoftheAMLA,promulgateduponthepassage

of R.A. No. 9194. With respect to freeze orders under Section 10, the implementing rules do expressly

providethattheapplicationsforfreezeordersbefiledexparte,75butnosimilarclearanceisgrantedinthe

case of inquiry orders under Section 11.76 These implementing rules were promulgated by the Bangko

SentralngPilipinas,theInsuranceCommissionandtheSecuritiesandExchangeCommission,77and if it

wasthetruebeliefoftheseinstitutionsthatinquiryorderscouldbeissuedexpartesimilartofreezeorders,

languagetothateffectwouldhavebeenincorporatedinthesaidRules.Thisisstressednotbecausethe

implementingrulescouldauthorizeexparteapplicationsforinquiryordersdespitetheabsenceofstatutory

basis,butratherbecausetheframersofthelawhadnointentiontoallowsuchexparteapplications.

EventheRulesofProcedureadoptedbythisCourtinA.M.No.051104SC78toenforcetheprovisionsof

theAMLAspecificallyauthorizeexparteapplicationswithrespecttofreezeordersunderSection1079but

makenosimilarauthorizationwithrespecttobankinquiryordersunderSection11.

TheCourtcoulddivinethesenseinallowingexparteproceedingsunderSection10andinproscribingthe

sameunderSection11.AfreezeorderunderSection10ontheonehandisaimedatpreservingmonetary

instruments or property in any way deemed related to unlawful activities as defined in Section 3(i) of the

AMLA.Theownerofsuchmonetaryinstrumentsorpropertywouldthusbeinhibitedfromutilizingthesame

for the duration of the freeze order. To make such freeze order anteceded by a judicial proceeding with

noticetotheaccountholderwouldallowfororleadtothedissipationofsuchfundsevenbeforetheorder

couldbeissued.

On the other hand, a bank inquiry order under Section 11 does not necessitate any form of physical

seizureofpropertyoftheaccountholder.Whatthebankinquiryorderauthorizesistheexaminationofthe

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

7/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

particular deposits or investments in banking institutions or nonbank financial institutions. The monetary

instruments or property deposited with such banks or financial institutions are not seized in a physical

sense, but are examined on particular details such as the account holders record of deposits and

transactions. Unlike the assets subject of the freeze order, the records to be inspected under a bank

inquiry order cannot be physically seized or hidden by the account holder. Said records are in the

possessionofthebankandthereforecannotbedestroyedattheinstanceoftheaccountholderaloneas

thatwouldrequiretheextraordinarycooperationanddevotionofthebank.

Interestingly, petitioners memorandum does not attempt to demonstrate before the Court that the bank

inquiryorderunderSection11maybeissuedexparte,althoughthepetitionitselfdiddevotesomespace

forthatargument.Thepetitionarguesthatthebankinquiryorderis"aspecialandpeculiarremedy,drastic

initsname,andmadenecessarybecauseofapublicnecessity[t]hus,byitsverynature,theapplication

foranorderorinquirymustnecessarily,beexparte."Thisargumentisinsufficientjustificationinlightofthe

cleardisinclinationofCongresstoallowtheissuanceexparteofbankinquiryordersunderSection11,in

contrasttothelegislaturesclearinclinationtoallowtheexpartegrantoffreezeordersunderSection10.

Without doubt, a requirement that the application for a bank inquiry order be done with notice to the

account holder will alert the latter that there is a plan to inspect his bank account on the belief that the

fundsthereinareinvolvedinanunlawfulactivityormoneylaunderingoffense.80Still,theaccountholderso

alertedwillinfactbeunabletodoanythingtoconcealorcleansehisbankaccountrecordsofsuspiciousor

anomaloustransactions,atleastnotwithoutthewholeheartedcooperationofthebank,whichinherently

hasnovestedinteresttoaidtheaccountholderinsuchmanner.

V.

The necessary implication of this finding that Section 11 of the AMLA does not generally authorize the

issuanceexparteof the bank inquiry order would be that such orders cannot be issued unless notice is

given to the owners of the account, allowing them the opportunity to contest the issuance of the order.

Without such a consequence, the legislated distinction between ex parte proceedings under Section 10

andthosewhicharenotexparteunderSection11wouldbelostandrendereduseless.

Therecertainlyisfertilegroundtocontesttheissuanceofanexparteorder.Section11itselfrequiresthat

it be established that "there is probable cause that the deposits or investments are related to unlawful

activities," and it obviously is the court which stands as arbiter whether there is indeed such probable

cause. The process of inquiring into the existence of probable cause would involve the function of

determinationreposedonthetrialcourt.Determinationclearlyimpliesafunctionofadjudicationonthepart

of the trial court, and not a mechanical application of a standard predetermination by some other body.

The word "determination" implies deliberation and is, in normal legal contemplation, equivalent to "the

decisionofacourtofjustice."81

The court receiving the application for inquiry order cannot simply take the AMLCs word that probable

causeexiststhatthedepositsorinvestmentsarerelatedtoanunlawfulactivity.Itwillhavetoexerciseits

own determinative function in order to be convinced of such fact. The account holder would be certainly

capable of contesting such probable cause if given the opportunity to be apprised of the pending

applicationtoinquireintohisaccounthenceanoticerequirementwouldnotbeanemptyspectacle.Itmay

be so that the process of obtaining the inquiry order may become more cumbersome or prolonged

becauseofthenoticerequirement,yetwefailtoseeanyunreasonableburdencastbysuchcircumstance.

Afterall,asearlierstated,requiringnoticetotheaccountholdershouldnot,inanyway,compromisethe

integrityofthebankrecordssubjectoftheinquirywhichremaininthepossessionandcontrolofthebank.

Petitionerarguesthatabankinquiryordernecessitatesafindingofprobablecause,acharacteristicsimilar

to a search warrant which is applied to and heard ex parte. We have examined the supposed analogy

betweenasearchwarrantandabankinquiryorderyetweremaintobeunconvincedbypetitioner.

TheConstitutionandtheRulesofCourtprescribeparticularrequirementsattachingtosearchwarrantsthat

arenotimposedbytheAMLAwithrespecttobankinquiryorders.Aconstitutionalwarrantrequiresthatthe

judge personally examine under oath or affirmation the complainant and the witnesses he may

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

8/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

produce,82 such examination being in the form of searching questions and answers.83 Those are

impositionswhichthelegislativedidnotspecificallyprescribeastothebankinquiryorderundertheAMLA,

and we cannot find sufficient legal basis to apply them to Section 11 of the AMLA. Simply put, a bank

inquiry order is not a search warrant or warrant of arrest as it contemplates a direct object but not the

seizureofpersonsorproperty.

EvenastheConstitutionandtheRulesofCourtimposeahighproceduralstandardforthedetermination

ofprobablecausefortheissuanceofsearchwarrantswhichCongresschosenottoprescribeforthebank

inquiryorderundertheAMLA,Congressnonethelessdisallowedexparteapplicationsfortheinquiryorder.

We can discern that in exchange for these procedural standards normally applied to search warrants,

Congress chose instead to legislate a right to notice and a right to be heard characteristics of judicial

proceedingswhicharenotexparte.Absentanydemonstrableconstitutionalinfirmity,thereisnoreasonfor

ustodisputesuchlegislativepolicychoices.

VI.

The Courts construction of Section 11 of the AMLA is undoubtedly influenced by right to privacy

considerations. If sustained, petitioners argument that a bank account may be inspected by the

government following anexparteproceeding about which the depositor would know nothing would have

significant implications on the right to privacy, a right innately cherished by all notwithstanding the legally

recognized exceptions thereto. The notion that the government could be so empowered is cause for

concernofanyindividualwhovaluestherighttoprivacywhich,afterall,embodieseventherighttobe"let

alone,"themostcomprehensiveofrightsandtherightmostvaluedbycivilizedpeople.84

One might assume that the constitutional dimension of the right to privacy, as applied to bank deposits,

warrants our present inquiry. We decline to do so. Admittedly, that question has proved controversial in

Americanjurisprudence.Notably,theUnitedStatesSupremeCourtinU.S.v.Miller85heldthattherewas

no legitimate expectation of privacy as to the bank records of a depositor.86 Moreover, the text of our

Constitutionhasnotbotheredwiththetrivialityofallocatingspecificrightspeculiartobankdeposits.

However,sufficientforourpurposes,wecanassertthereisarighttoprivacygoverningbankaccountsin

the Philippines, and that such right finds application to the case at bar. The source of such right is

statutory,expressedasitisinR.A.No.1405otherwiseknownastheBankSecrecyActof1955.Theright

toprivacyisenshrinedinSection2ofthatlaw,towit:

SECTION 2. All deposits of whatever nature with banks or banking institutions in the

PhilippinesincludinginvestmentsinbondsissuedbytheGovernmentofthePhilippines,its

political subdivisions and its instrumentalities, are hereby considered as of an absolutely

confidentialnatureandmaynotbeexamined,inquiredorlookedintobyanyperson,government

official, bureau or office, except upon written permission of the depositor, or in cases of

impeachment,oruponorderofacompetentcourtincasesofbriberyorderelictionofdutyofpublic

officials, or in cases where the money deposited or invested is the subject matter of the litigation.

(Emphasissupplied)

Because of the Bank Secrecy Act, the confidentiality of bank deposits remains a basic state policy in the

Philippines.87Subsequentlaws,includingtheAMLA,mayhaveaddedexceptionstotheBankSecrecyAct,

yetthesecrecyofbankdepositsstillliesasthegeneralrule.Itfallswithinthezonesofprivacyrecognized

by our laws.88The framers of the 1987 Constitution likewise recognized that bank accounts are not

covered by either the right to information89 under Section 7, Article III or under the requirement of full

publicdisclosure90underSection28,ArticleII.91UnlesstheBankSecrecyActisrepealedor

amended, the legal order is obliged to conserve the absolutely confidential nature of Philippine bank

deposits.

Any exception to the rule of absolute confidentiality must be specifically legislated. Section 2 of the Bank

SecrecyActitselfprescribesexceptionswherebythesebankaccountsmaybeexaminedby"anyperson,

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2

9/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

government official, bureau or office" namely when: (1) upon written permission of the depositor (2) in

casesofimpeachment(3)theexaminationofbankaccountsisuponorderofacompetentcourtincases

of bribery or dereliction of duty of public officials and (4) the money deposited or invested is the subject

matterofthelitigation.Section8ofR.A.ActNo.3019,theAntiGraftandCorruptPracticesAct,hasbeen

recognizedbythisCourtasconstitutinganadditionalexceptiontotheruleofabsoluteconfidentiality,92and

therehavebeenothersimilarrecognitionsaswell.93

TheAMLAalsoprovidesexceptionstotheBankSecrecyAct.UnderSection11,theAMLCmayinquireinto

a bank account upon order of any competent court in cases of violation of the AMLA, it having been

establishedthatthereisprobablecausethatthedepositsorinvestmentsarerelatedtounlawfulactivities

as defined in Section 3(i) of the law, or a money laundering offense under Section 4 thereof. Further, in

instances where there is probable cause that the deposits or investments are related to kidnapping for

ransom,94certain violations of the Comprehensive Dangerous Drugs Act of 2002,95 hijacking and other

violations under R.A. No. 6235, destructive arson and murder, then there is no need for the AMLC to

obtainacourtorderbeforeitcouldinquireintosuchaccounts.

ItcannotbesuccessfullyarguedtheproceedingsrelatingtothebankinquiryorderunderSection11ofthe

AMLAisa"litigation"encompassedinoneoftheexceptionstotheBankSecrecyActwhichiswhen"the

money deposited or invested is the subject matter of the litigation." The orientation of the bank inquiry

orderissimplytoserveasaprovisionalrelieforremedy.Asearlierstated,theapplicationforsuchdoes

notentailafullblowntrial.

Nevertheless,justbecausetheAMLAestablishesadditionalexceptionstotheBankSecrecyActitdoesnot

mean that the later law has dispensed with the general principle established in the older law that "[a]ll

deposits of whatever nature with banks or banking institutions in the Philippines x x x are hereby

considered as of an absolutely confidential nature."96 Indeed, by force of statute, all bank deposits are

absolutely confidential, and that nature is unaltered even by the legislated exceptions referred to above.

There is disfavor towards construing these exceptions in such a manner that would authorize unlimited

discretiononthepartofthegovernmentorofanypartyseekingtoenforcethoseexceptionsandinquire

into bank deposits. If there are doubts in upholding the absolutely confidential nature of bank deposits

againstaffirmingtheauthoritytoinquireintosuchaccounts,thensuchdoubtsmustberesolvedinfavorof

theformer.SuchastancewouldpersistunlessCongresspassesalawreversingthegeneralstatepolicyof

preservingtheabsolutelyconfidentialnatureofPhilippinebankaccounts.

Thepresenceofthisstatutoryrighttoprivacyaddressesatleastoneoftheargumentsraisedbypetitioner,

that Lilia Cheng had no personality to assail the inquiry orders before the Court of Appeals because she

wasnotthesubjectofsaidorders.AMLCResolutionNo.75,whichservedasthebasisinthesuccessful

application for the Makati inquiry order, expressly adverts to Citibank Account No. 88576248 "owned by

ChengYongand/orLiliaG.ChengwithCitibankN.A.,"97whereasLiliaChengspetitionbeforetheCourtof

Appeals is accompanied by a certification from Metrobank that Account Nos. 3008524360 and

7001498017,bothofwhichareamongthesubjectsoftheManilainquiryorder,areaccountsinthename

of "Yong Cheng or Lilia Cheng."98 Petitioner does not specifically deny that Lilia Cheng holds rights of

ownership over the three said accounts, laying focus instead on the fact that she was not named as a

subjectofeithertheMakatiorManilaRTCinquiryorders.WearereasonablyconvincedthatLiliaCheng

has sufficiently demonstrated her joint ownership of the three accounts, and such conclusion leads us to

acknowledge that she has the standing to assail via certiorari the inquiry orders authorizing the

examinationofherbankaccountsastheordersinterferewithherstatutoryrighttomaintainthesecrecyof

saidaccounts.

While petitioner would premise that the inquiry into Lilia Chengs accounts finds root in Section 11 of the

AMLA,itcannotbedeniedthattheauthoritytoinquireunderSection11isonlyexceptionalincharacter,

contraryasitistothegeneralrulepreservingthesecrecyofbankdeposits.Eventhoughshemaynothave

been the subject of the inquiry orders, her bank accounts nevertheless were, and she thus has the

standing to vindicate the right to secrecy that attaches to said accounts and their owners. This statutory

right to privacy will not prevent the courts from authorizing the inquiry anyway upon the fulfillment of the

requirements set forth under Section 11 of the AMLA or Section 2 of the Bank Secrecy Act at the same

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2 10/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

time, the owner of the accounts have the right to challenge whether the requirements were indeed

compliedwith.

VII.

Thereisafinalpointofconcernwhichneedstobeaddressed.LiliaChengarguesthattheAMLA,beinga

substantivepenalstatute,hasnoretroactiveeffectandthebankinquiryordercouldnotapplytodeposits

or investments opened prior to the effectivity of Rep. Act No. 9164, or on 17 October 2001. Thus, she

concludes,hersubjectbankaccounts,openedbetween1989to1990,couldnotbethesubjectofthebank

inquiryorderlesttherebeaviolationoftheconstitutionalprohibitionagainstexpostfactolaws.

No ex post facto law may be enacted,99 and no law may be construed in such fashion as to permit a

criminalprosecutionoffensivetotheexpostfactoclause.AsappliedtotheAMLA,itisplainthatnoperson

maybeprosecutedunderthepenalprovisionsoftheAMLAforactscommittedpriortotheenactmentof

thelawon17October2001.Asmuchwasunderstoodbythelawmakerssincetheydeliberateduponthe

AMLA,andindeedthereisnoseriousdisputeonthatpoint.

DoestheproscriptionagainstexpostfactolawsapplytotheinterpretationofSection11,aprovisionwhich

doesnotprovideforapenalsanctionbutwhichmerelyauthorizestheinspectionofsuspectaccountsand

deposits?Theanswerisintheaffirmative.Inthisjurisdiction,wehavedefinedanexpostfactolawasone

whicheither:

(1)makescriminalanactdonebeforethepassageofthelawandwhichwasinnocentwhendone,

andpunishessuchanact

(2)aggravatesacrime,ormakesitgreaterthanitwas,whencommitted

(3) changes the punishment and inflicts a greater punishment than the law annexed to the crime

whencommitted

(4)altersthelegalrulesofevidence,andauthorizesconvictionuponlessordifferenttestimonythan

thelawrequiredatthetimeofthecommissionoftheoffense

(5)assumingtoregulatecivilrightsandremediesonly,ineffectimposespenaltyordeprivationofa

rightforsomethingwhichwhendonewaslawfuland

(6)deprivesapersonaccusedofacrimeofsomelawfulprotectiontowhichhehasbecome

entitled, such as the protection of a former conviction or acquittal, or a proclamation of

amnesty.(Emphasissupplied)100

PriortotheenactmentoftheAMLA,thefactthatbankaccountsordepositswereinvolvedinactivitieslater

onenumeratedinSection3ofthelawdidnot,byitself,removesuchaccountsfromtheshelterofabsolute

confidentiality. Prior to the AMLA, in order that bank accounts could be examined, there was need to

secure either the written permission of the depositor or a court order authorizing such examination,

assumingthattheywereinvolvedincasesofbriberyorderelictionofdutyofpublicofficials,orinacase

wherethemoneydepositedorinvestedwasitselfthesubjectmatterofthelitigation.Thepassageofthe

AMLA stripped another layer off the rule on absolute confidentiality that provided a measure of lawful

protectiontotheaccountholder.Forthatreason,theapplicationofthebankinquiryorderasameansof

inquiring into records of transactions entered into prior to the passage of the AMLA would be

constitutionallyinfirm,offensiveasitistotheexpostfactoclause.

Still,wemustnotethatthepositionsubmittedbyLiliaChengismuchbroaderthanwhatwearewillingto

affirm.Shearguesthattheproscriptionagainstexpostfactolawsgoesasfarastoprohibitanyinquiryinto

depositsorinvestmentsincludedinbankaccountsopenedpriortotheeffectivityoftheAMLAevenifthe

suspecttransactionswereenteredintowhenthelawhadalreadytakeneffect.TheCourtrecognizesthatif

thisargumentweretobeaffirmed,itwouldcreateahorribleloopholeintheAMLAthatwouldinturnsupply

themeanstofearlesslyengageinmoneylaunderinginthePhilippinesallthatthecriminalhastodoisto

makesurethatthemoneylaunderingactivityisfacilitatedthroughabankaccountopenedpriorto2001.

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2 11/12

3/10/2015

G.R.No.174629

Lilia Cheng admits that "actual money launderers could utilize the ex post facto provision of the

Constitutionasashield"butthattheremedylaywithCongresstoamendthelaw.Wecanhardlypresume

that Congress intended to enact a selfdefeating law in the first place, and the courts are inhibited from

suchaconstructionbythecardinalrulethat"alawshouldbeinterpretedwithaviewtoupholdingrather

thandestroyingit."101

Besides, nowhere in the legislative record cited by Lilia Cheng does it appear that there was an

unequivocalintenttoexemptfromthebankinquiryorderallbankaccountsopenedpriortothepassageof

theAMLA.ThereisacitedexchangebetweenRepresentativesRonaldoZamoraandJaimeLopezwhere

thelatterconfirmedtotheformerthat"depositsaresupposedtobeexemptedfromscrutinyormonitoring

if they are already in place as of the time the law is enacted."102 That statement does indicate that

transactionsalreadyinplacewhentheAMLAwaspassedareindeedexemptfromscrutinythroughabank

inquiry order, but it cannot yield any interpretation that records of transactions undertaken after the

enactment of the AMLA are similarly exempt. Due to the absence of cited authority from the legislative

recordthatunqualifiedlysupportsrespondentLiliaChengsthesis,thereisnocauseforustosustainher

interpretationoftheAMLA,fatalasitistotheanimaofthatlaw.

IX.

WearewellawarethatLiliaChengspetitionpresentlypendingbeforetheCourtofAppealslikewiseassails

the validity of the subject bank inquiry orders and precisely seeks the annulment of said orders. Our

currentdeclarationsmayindeedhavetheeffectofpreemptingthat0petition.Still,inorderforthisCourtto

ruleonthepetitionatbarwhichinsistsontheenforceabilityofthesaidbankinquiryorders,itisnecessary

forustoconsiderandruleonthesamequestionwhichafterallisapurequestionoflaw.

WHEREFORE,thePETITIONisDISMISSED.Nopronouncementastocosts.

SOORDERED.

DANTEO.TINGA

AssociateJustice

data:text/htmlcharset=utf8,%3Cp%20style%3D%22fontsize%3A%2014px%3B%20textdecoration%3A%20none%3B%20color%3A%20rgb(0%2C%200%2 12/12

You might also like

- Amla Jurisprudence G.R. No. 174629Document19 pagesAmla Jurisprudence G.R. No. 174629Quijano MykNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: Second DivisionDocument20 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: Second DivisionjackyNo ratings yet

- Petitioner Vs Vs Respondents: Second DivisionDocument20 pagesPetitioner Vs Vs Respondents: Second DivisionElieNo ratings yet

- 154195-2008-Republic v. Eugenio Jr.Document20 pages154195-2008-Republic v. Eugenio Jr.Louie BruanNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 174629Document15 pagesG.R. No. 174629Julia PoncianoNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs Hon. EugenioDocument16 pagesRepublic Vs Hon. EugenioPACNo ratings yet

- REPUBLIC vs. EUGENIODocument17 pagesREPUBLIC vs. EUGENIOBiaNo ratings yet

- 1 Digest Republic Vs EugenioDocument3 pages1 Digest Republic Vs EugeniorizaNo ratings yet

- Bill of Rights Ex Post Facto ProhibitionDocument23 pagesBill of Rights Ex Post Facto ProhibitionJenNo ratings yet

- Sec. 22. Ex Post Facto Law I.: vs. Hon. Antonio M. Eugenio, JRDocument3 pagesSec. 22. Ex Post Facto Law I.: vs. Hon. Antonio M. Eugenio, JRAnna HulyaNo ratings yet

- People v. ManaloDocument5 pagesPeople v. ManaloKristoffer PepinoNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Vs Hon. Antonio M. Eugenio, Jr. - DigestDocument2 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Vs Hon. Antonio M. Eugenio, Jr. - DigestJan Michael Jay CuevasNo ratings yet

- Republic v Eugenio Case on Bank Inquiry OrdersDocument5 pagesRepublic v Eugenio Case on Bank Inquiry OrdersadeeNo ratings yet

- 1 Republic V Eugenio Case DigestDocument3 pages1 Republic V Eugenio Case Digestamor83% (6)

- Republic of The Philippines vs. Eugenio G.R. No. 174629 February 14, 2008 Tinga, J.: FactsDocument3 pagesRepublic of The Philippines vs. Eugenio G.R. No. 174629 February 14, 2008 Tinga, J.: FactsAdi LimNo ratings yet

- Mercantile Law-Republic vs. ManaloDocument6 pagesMercantile Law-Republic vs. ManaloKat Agpoon-AbadNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 192302, June 04, 2014Document7 pagesG.R. No. 192302, June 04, 2014kai lumagueNo ratings yet

- Motu Proprio To The Court en BancDocument15 pagesMotu Proprio To The Court en BancLaw SSCNo ratings yet

- Digests 3rd BatchDocument4 pagesDigests 3rd Batchjon jonNo ratings yet

- Valero V of Ce of OmbudsmanDocument14 pagesValero V of Ce of OmbudsmanLaw SSCNo ratings yet

- Africa V Pcgg. GR 83831. Jan 9, 1992. 205 Scra 39Document12 pagesAfrica V Pcgg. GR 83831. Jan 9, 1992. 205 Scra 39Charles DumasiNo ratings yet

- 27 CommentDocument46 pages27 Commentherbs22225847100% (1)

- Marquez vs. Desierto, G.R. No. 135882, June 27, 2001Document5 pagesMarquez vs. Desierto, G.R. No. 135882, June 27, 2001Xtine CampuPotNo ratings yet

- Customs official dismissal upheldDocument17 pagesCustoms official dismissal upheldaspiringlawyer1234No ratings yet

- Bank Wins Case but Sheriff Found in ContemptDocument5 pagesBank Wins Case but Sheriff Found in ContemptSaima RodeuNo ratings yet

- Tinga, J.: Republic v. Eugenio, Jr. 545 SCRA 384 (2008) Ponente: Statement of The CaseDocument14 pagesTinga, J.: Republic v. Eugenio, Jr. 545 SCRA 384 (2008) Ponente: Statement of The CaseNikki Estores GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Marquez Vs DisiertoDocument6 pagesMarquez Vs DisiertoVanessa Canceran AlporhaNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines vs. Eugenio G.R. No. 174629 February 14, 2008 Tinga, J.: FactsDocument19 pagesRepublic of The Philippines vs. Eugenio G.R. No. 174629 February 14, 2008 Tinga, J.: FactsAdi LimNo ratings yet

- Republic v. EugenioDocument4 pagesRepublic v. EugenioTon RiveraNo ratings yet

- 039 Marquez v. Desierto, G.R. No. 135882Document5 pages039 Marquez v. Desierto, G.R. No. 135882Julius Albert SariNo ratings yet

- D. AMLA Republic of PH Vs EugenioDocument2 pagesD. AMLA Republic of PH Vs EugenioDjenral Wesley SorianoNo ratings yet

- October 14 Banking DigestDocument12 pagesOctober 14 Banking DigestLenette LupacNo ratings yet

- Camera Relative To Various Accounts Maintained at Union Bank of The Philippines, Julia VargasDocument6 pagesCamera Relative To Various Accounts Maintained at Union Bank of The Philippines, Julia VargasMark TeaNo ratings yet

- Koruga vs. Arcenas, Et. Al., G.R. No. 168332, June 19, 2009Document16 pagesKoruga vs. Arcenas, Et. Al., G.R. No. 168332, June 19, 2009Gilbert John LacorteNo ratings yet

- Facts:: Exemption Against GarnishmentDocument6 pagesFacts:: Exemption Against GarnishmentWresen Ann JavaluyasNo ratings yet

- 1993 Nuez - v. - Balles20240109 11 LGLDBLDocument4 pages1993 Nuez - v. - Balles20240109 11 LGLDBLSteph GeeNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Vs CA 200scra226Document10 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Vs CA 200scra226mansikiaboNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Ruling on Anti-Graft Law ViolationsDocument153 pagesSupreme Court Ruling on Anti-Graft Law ViolationsJan Kenrick SagumNo ratings yet

- Custom Search: Today Is Friday, September 29, 2017Document10 pagesCustom Search: Today Is Friday, September 29, 2017Donald Dwane ReyesNo ratings yet

- Republic v. EugenioDocument3 pagesRepublic v. EugenioTon RiveraNo ratings yet

- Turner v. LorenzoDocument36 pagesTurner v. Lorenzodeuce scriNo ratings yet

- Guillermo Salvador Vs Patricia, Inc. (Jurisdiction Is Conferred by Law)Document15 pagesGuillermo Salvador Vs Patricia, Inc. (Jurisdiction Is Conferred by Law)Zyrene CabaldoNo ratings yet

- Philsa International Placement Vs Sec of LaborDocument11 pagesPhilsa International Placement Vs Sec of LaborChristopher Joselle MolatoNo ratings yet

- Court Dismisses UniAlloy Case Due to Improper VenueDocument29 pagesCourt Dismisses UniAlloy Case Due to Improper VenueAziel Marie C. GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Petitioners Vs Vs Ex-Of Cio Ex-Of Cio Respondents: Second DivisionDocument10 pagesPetitioners Vs Vs Ex-Of Cio Ex-Of Cio Respondents: Second DivisionChristine Ang CaminadeNo ratings yet

- 30 - Ombudsman Vs ValeraDocument7 pages30 - Ombudsman Vs ValeraRogelio Rubellano IIINo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument3 pagesCase DigestRosalyn Pagatpatan BarolaNo ratings yet

- Admin Law - 2nd BatchDocument90 pagesAdmin Law - 2nd BatchSharmila AbieraNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila: Eleventh DivisionDocument11 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila: Eleventh Divisionviktor samuel fontanillaNo ratings yet

- Bank Secrecy Act - Maruqez vs. DesiertoDocument6 pagesBank Secrecy Act - Maruqez vs. DesiertoStephanie Reyes GoNo ratings yet

- SEC Division: Court of Tax AppealsDocument21 pagesSEC Division: Court of Tax AppealsEdmund Earl Timothy Hular Burdeos IIINo ratings yet

- Republic V. Judge Eugenio G.R. NO. 174629, 14 FEBRUARY 2008 FactsDocument12 pagesRepublic V. Judge Eugenio G.R. NO. 174629, 14 FEBRUARY 2008 FactsMariam BautistaNo ratings yet

- Intro To Law CasesDocument36 pagesIntro To Law CasesBeñalim BunoNo ratings yet

- Valera v. OmbudsmanDocument11 pagesValera v. OmbudsmanGavin Reyes CustodioNo ratings yet

- Commission On Elections v. EspañolDocument14 pagesCommission On Elections v. EspañolAlex FranciscoNo ratings yet

- Sandiganbayan Despite The Ostensibly Mandatory Language" of The Statute, and That That Discretion Was GravelyDocument8 pagesSandiganbayan Despite The Ostensibly Mandatory Language" of The Statute, and That That Discretion Was Gravelyrols villanezaNo ratings yet

- Petitioners Vs VS: Third DivisionDocument11 pagesPetitioners Vs VS: Third DivisionJM CamposNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionFrom EverandSupreme Court Eminent Domain Case 09-381 Denied Without OpinionNo ratings yet

- Petition for Extraordinary Writ Denied Without Opinion– Patent Case 94-1257From EverandPetition for Extraordinary Writ Denied Without Opinion– Patent Case 94-1257No ratings yet

- Petition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413From EverandPetition for Certiorari: Denied Without Opinion Patent Case 93-1413No ratings yet

- Property CasesDocument7 pagesProperty CasesJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Africa vs. Caltex L-12986 (TORTS)Document1 pageAfrica vs. Caltex L-12986 (TORTS)Jacinto Jr Jamero100% (1)

- PEOPLE Vs Sandiganbayan GR# 115439-41Document8 pagesPEOPLE Vs Sandiganbayan GR# 115439-41Jacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- REGALA Vs SandiganbayanDocument16 pagesREGALA Vs SandiganbayanJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Mitmug Vs Comelec - DigestDocument1 pageMitmug Vs Comelec - DigestJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Diaz vs. Secretary of Finance - VAT on Toll FeesDocument2 pagesDiaz vs. Secretary of Finance - VAT on Toll FeesCayen Cervancia CabiguenNo ratings yet

- Hickman v Taylor Work Product DoctrineDocument4 pagesHickman v Taylor Work Product DoctrineJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Agner Vs BPIDocument5 pagesAgner Vs BPIJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Notes On Jurisdiction of CourtsDocument7 pagesNotes On Jurisdiction of CourtsJacinto Jr Jamero100% (1)

- Montesclaros vs. Comelec, G.R. No. 152295, July 9, 2002Document6 pagesMontesclaros vs. Comelec, G.R. No. 152295, July 9, 2002Jacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- People V TandoyDocument6 pagesPeople V TandoyJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Chamber vs. Romulo 614 SCRA 605 2010Document17 pagesChamber vs. Romulo 614 SCRA 605 2010Jacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Lee vs. CA GR No. L - 37135Document7 pagesLee vs. CA GR No. L - 37135Jacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Villa Rey Transit v. FerrerDocument8 pagesVilla Rey Transit v. FerrerJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Diaz vs. Secretary of Finance - VAT on Toll FeesDocument2 pagesDiaz vs. Secretary of Finance - VAT on Toll FeesCayen Cervancia CabiguenNo ratings yet

- Lee vs. CA GR No. L - 37135Document7 pagesLee vs. CA GR No. L - 37135Jacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- People Vs TanDocument2 pagesPeople Vs TanJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- HusseinDocument5 pagesHusseinWilsonNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 83907. September 13, 1989. NAPOLEON GEGARE, PetitionerDocument4 pagesG.R. No. 83907. September 13, 1989. NAPOLEON GEGARE, PetitionerØbęy HårryNo ratings yet

- Tax TablesDocument4 pagesTax TablesJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- People V TandoyDocument6 pagesPeople V TandoyJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- De Vera v. AguilarDocument3 pagesDe Vera v. AguilarJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- RA 7432 - Senior Citizens ActDocument5 pagesRA 7432 - Senior Citizens ActChristian Mark Ramos GodoyNo ratings yet

- Villa Rey Transit v. FerrerDocument8 pagesVilla Rey Transit v. FerrerJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Yessesin-Volpin V Novosti Press Agency - DIGESTDocument2 pagesYessesin-Volpin V Novosti Press Agency - DIGESTJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Marcos Asset Dispute: 9th Circuit Applies "Act of State" DoctrineDocument4 pagesMarcos Asset Dispute: 9th Circuit Applies "Act of State" DoctrineJacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- BIR RR 07-2003Document8 pagesBIR RR 07-2003Brian BaldwinNo ratings yet

- Tax RateDocument10 pagesTax RateErwin Dave M. DahaoNo ratings yet

- A.W. Fluemer vs. Annie Hix, G.R. No. L-32636, March 17, 1930Document1 pageA.W. Fluemer vs. Annie Hix, G.R. No. L-32636, March 17, 1930Sarah Jane-Shae O. SemblanteNo ratings yet

- Philsec vs. Ca - FullDocument6 pagesPhilsec vs. Ca - FullERNIL L BAWANo ratings yet

- Set Up A Mail Server On LinuxDocument56 pagesSet Up A Mail Server On Linuxammurasikan6477No ratings yet

- A Future For The World's Children?: The Numbers That CountDocument20 pagesA Future For The World's Children?: The Numbers That CountCarmen PalimariuNo ratings yet

- 2 C Program StructureDocument13 pages2 C Program StructurePargi anshuNo ratings yet

- Integrated Farming System: A ReviewDocument12 pagesIntegrated Farming System: A ReviewIndian Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences RNo ratings yet

- Software Engineering Chapter 6 ExercisesDocument4 pagesSoftware Engineering Chapter 6 Exercisesvinajanebalatico81% (21)

- Approved Term of Payment For Updating Lower LagunaDocument50 pagesApproved Term of Payment For Updating Lower LagunaSadasfd SdsadsaNo ratings yet

- Johannes GutenbergDocument6 pagesJohannes GutenbergMau ReenNo ratings yet

- Holiday Homework - CommerceDocument3 pagesHoliday Homework - CommerceBhavya JainNo ratings yet

- 2008 Consumer Industry Executive SummaryDocument139 pages2008 Consumer Industry Executive SummaryzampacaanasNo ratings yet

- Training MatrixDocument4 pagesTraining MatrixJennyfer Banez Nipales100% (1)

- Mid-Term Test RemedialDocument2 pagesMid-Term Test RemedialgaliihputrobachtiarzenNo ratings yet

- Flyrock Prediction FormulaeDocument5 pagesFlyrock Prediction FormulaeAmy LatawanNo ratings yet

- Soap Making BooksDocument17 pagesSoap Making BooksAntingero0% (2)

- Jan 2012Document40 pagesJan 2012Daneshwer Verma100% (1)

- CISSPDocument200 pagesCISSPkumarNo ratings yet

- VideosDocument5 pagesVideosElvin Joseph Pualengco MendozaNo ratings yet

- BITUMINOUS MIX DESIGNDocument4 pagesBITUMINOUS MIX DESIGNSunil BoseNo ratings yet

- Inbound 6094510472110192055Document2 pagesInbound 6094510472110192055MarielleNo ratings yet

- The Structural Engineer - August 2022 UPDATEDDocument36 pagesThe Structural Engineer - August 2022 UPDATEDES100% (1)

- PT Amar Sejahtera General LedgerDocument6 pagesPT Amar Sejahtera General LedgerRiska GintingNo ratings yet

- Z8T Chassis (TX-21AP1P)Document10 pagesZ8T Chassis (TX-21AP1P)Петро ДуманськийNo ratings yet

- FS Chapter 1Document2 pagesFS Chapter 1Jonarissa BeltranNo ratings yet

- China Identity Verification (FANTASY TECH)Document265 pagesChina Identity Verification (FANTASY TECH)Kamal Uddin100% (1)

- Comparator: Differential VoltageDocument8 pagesComparator: Differential VoltageTanvir Ahmed MunnaNo ratings yet

- Leak Proof Engineering I PVT LTDDocument21 pagesLeak Proof Engineering I PVT LTDapi-155731311No ratings yet

- North American Series 4762 Immersion Tube Burners 4762 - BULDocument4 pagesNorth American Series 4762 Immersion Tube Burners 4762 - BULedgardiaz5519No ratings yet

- Ans: DDocument10 pagesAns: DVishal FernandesNo ratings yet

- Approved Local Government Taxes and Levies in Lagos StateDocument5 pagesApproved Local Government Taxes and Levies in Lagos StateAbū Bakr Aṣ-Ṣiddīq50% (2)

- Blackman Et Al 2013Document18 pagesBlackman Et Al 2013ananth999No ratings yet

- Amado Vs Salvador DigestDocument4 pagesAmado Vs Salvador DigestEM RGNo ratings yet