Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Consti Final

Uploaded by

MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Consti Final

Uploaded by

MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoCopyright:

Available Formats

EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT

I.

Past midnight, in the early hours of June 24, 2004, the

Congress acting as the National Board of

Canvassers, in a near-unanimous roll-call vote,

proclaimed Mrs. Arroyo the duly elected President of

the Philippines. Refusing to concede defeat, the

second-placer in the elections, Mr. Poe, filed

seasonably an election protest before this Electoral

Tribunal. As counsels for the parties exchanged lively

motions to rush the presentation of their respective

positions on the controversy, an act of God

intervened. Mr. Poe died in the course of his medical

treatment at St. Lukes Hospital. However, neither the

Arroyos proclamation by Congress nor the death of

her main rival as a fortuitous intervening event

appears to abate the present controversy in the public

arena. Together with the formal Notice of the Death of

Protestant, his counsel has submitted to the Tribunal,

dated January 10, 2005, a MANIFESTATION with

URGENT PETITION/MOTION to INTERVENE AS A

SUBSTITUTE FOR DECEASED PROTESTANT Mrs.

Susan Roces-Poe, by the widow, Mrs. Roces, who

signed the verification and certification therein. Can

Mrs. Roces-Poe substitute his late husband in the

electoral protest against Mrs. Arroyo?

Answer: No. Pursuant to PET rule, only two

persons, the 2nd and 3rd placers, may contest the

election. By this express enumeration, the rule

makers have in effect determined the real parties in

interest concerning an on-going election contest. It

envisioned a scenario where, if the declared winner

had not been truly voted upon by the electorate, the

candidate who received that 2nd or the 3rd highest

number of votes would be the legitimate beneficiary in

a successful election contest. If persons not real

parties in the action could be allowed to

intervene, proceedings will be unnecessarily

complicated, expensive and interminable and

this is not the policy of the law. (Poe, Jr. vs.

Arroyo, March 29, 2005).

II.

Congress sitting as the National Board of Canvassers

(NBC) proclaimed Mr. De Castro the duly elected

Vice-President of the Republic of the Philippines. Mrs.

Legarda, the second placer, filed a protest with the

PET for the annulment of the De Castro's

proclamation as the duly elected Vice-President of the

Republic of the Philippines. Subsequently, the Ms.

Legarda was elected as senator and discharged her

duties as such. Did Senator Legarda effectively

abandoned or withdrawn her protest?

Answer: In assuming the office of Senator and

discharging her duties as such, which fact the court

can take judicial notice of, has effectively

abandoned or withdrawn her protest, or

abandoned her determination to protect and

pursue the public interest involved in the matter

of who is the real choice of the electorate. It is

worthy to note that Legarda's tenure in the Senate

coincides with the term of the Vice-Presidency 20042010, that is the subject of her protest. (Legarda vs.

De Castro, 542 SCRA125).

III. Atty. Macalintal filed a petition that questions the

constitution of the Presidential Electoral Tribunal

(PET) as an illegal and unauthorized progeny of

Section 4, Article VII of the Constitution: The Supreme

Court, sitting en banc, shall be the sole judge of all

contests relating to the election, returns, and

qualifications of the President or Vice-President, and

may promulgate its rules for the purpose.

While he concedes that the Supreme Court is

"authorized to promulgate its rules for the purpose,

"he chafes at the creation of a purportedly "separate

tribunal" complemented by a budget allocation, a seal,

a set of personnel and confidential employees, to

effect the constitutional mandate. Further, he

reiterates that the constitution of the PET, with the

designation of the Members of the Court as Chairman

and Members thereof, contravenes Section 12, Article

VIII of the Constitution, which prohibits the

designation of Members of the Supreme Court and of

other courts established by law to any agency

performing quasi-judicial or administrative functions.

Is the constitution of the PET, composed of the

Members of this Court, unconstitutional for being

contrary to Section 4, Article VII and Section 12,

Article VIII of the Constitution?

Answer: No. The conferment of additional jurisdiction

to the Supreme Court, with the duty characterized as

an "awesome" task, includes the means necessary

to carry it into effect under the doctrine of

necessary implication. The PET is not a separate

and distinct entity from the Supreme Court, albeit

it has functions peculiar only to the Tribunal. It is

obvious that the PET was constituted in

implementation of Section 4, Article VII of the

Constitution, and it faithfully complies not unlawfully

defies the constitutional directive. The adoption of a

separate seal, as well as the change in the

nomenclature of the Chief Justice and the Associate

Justices into Chairman and Members of the Tribunal,

respectively, was designed simply to highlight the

singularity and exclusivity of the Tribunals

functions as a special electoral court.

As regards his claim that the PET exercises quasijudicial functions in contravention of Section 12,

Article VIII, the court said that the said issue is more

imagined than real. The power wielded by PET is a

derivative of the plenary judicial power allocated

to courts of law, expressly provided in the

Constitution. It is the Constitution itself, in Section

4, Article VII, which exempts the Members of the

Court, constituting the PET, from the said

prohibition. (Macalintal vs. PET, 635 SCRA 783 and

651 SCRA 239).

IV. Mr. Elma was appointed and took his oath of office as

Chairman of the PCGG. Thereafter, during his tenure

as PCGG Chairman, Mr. Elma was appointed Chief

Presidential Legal Counsel (CPLC). He took his oath

of office as CPLC the following day, but he waived

any remuneration that he may receive as CPLC.

Individuals filed an action to declare as null and void

the concurrent appointments of Mr. Elma as Chairman

of the PCGG and as Chief Presidential Legal Counsel

(CPLC) for being contrary to Section 13, Article VII

and Section 7, par. 2, Article IX-B of the 1987

Constitution.

Is the position of the PCGG Chairman or that of the

CPLC falls under the prohibition against multiple

offices imposed by Section 13, Article VII and Section

7, par. 2, Article IX-B of the 1987 Constitution?

Answer: To harmonize these two provisions, the

court said that the prohibition against multiple offices

contained in Section 7, Article IX-B and Section 13,

Article VII in this manner: [T]hus, while all other

appointive officials in the civil service are allowed to

hold other office or employment in the government

during their tenure when such is allowed by law or by

the primary functions of their positions, members of

the Cabinet, their deputies and assistants may do

so only when expressly authorized by the

Constitution itself. In other words, Section 7, Article

IX-B is meant to lay down the general rule applicable

to all elective and appointive public officials and

employees, while Section 13, Article VII is meant to

be the exception applicable only to the President, the

Vice-President, Members of the Cabinet, their

deputies and assistants.

The general rule contained in Article IX-B of the 1987

Constitution permits an appointive official to hold

more than one office only if "allowed by law or by

the primary functions of his position." In the case

of Quimson vs. Ozaeta, this Court ruled that, "[t]here

is no legal objection to a government official

occupying two government offices and performing the

functions of both as long as there is no

incompatibility." The crucial test in determining

whether incompatibility exists between two offices

was laid out in People vs. Green - whether one

office is subordinate to the other, in the sense that

one office has the right to interfere with the other.

Congress. In strict terms, presidential appointments

that require no confirmation from the Commission on

Appointments cannot be properly characterized as

either a regular or an ad interim appointment.

(General vs. Urro, 646 SCRA 567).

VIII. Is the concept of staggering of terms inconsistent with the

nature of acting appointments?

In this case, an incompatibility exists between the

positions of the PCGG Chairman and the CPLC.

The duties of the CPLC include giving independent

and impartial legal advice on the actions of the heads

of various executive departments and agencies and to

review investigations involving heads of executive

departments and agencies, as well as other

Presidential appointees. The PCGG is, without

question, an agency under the Executive Department.

Thus, the actions of the PCGG Chairman are

subject to the review of the CPLC. (Public Interest

Center, Inc. vs. Elma, 494 SCRA 53 and 517 SCRA

336).

V.

A petition for prohibition seeks to enjoin Mison from

performing the functions of the Office of

Commissioner of the Bureau of Customs and

Carague, as Secretary of the Department of Budget,

from effecting disbursements in payment of Mison's

salaries and emoluments, on the ground that Mison's

appointment as Commissioner of the Bureau of

Customs is unconstitutional by reason of its not

having been confirmed by the Commission on

Appointments. Is the argument valid?

Answer: Generally, the purpose for staggering the

term of office is to minimize the appointing

authoritys opportunity to appoint a majority of

the members of a collegial body. It also intended to

ensure the continuity of the body and its policies. A

staggered term of office, however, is not a

statutory prohibition, direct or indirect, against

the issuance of acting or temporary appointment.

It does not negate the authority to issue acting or

temporary appointments that the Administrative Code

grants. (ibid).

IX. Can the President appoint acting secretaries without the

consent of the Commission on Appointments while

Congress is in session?

Answer: The office of a department secretary may

become vacant while Congress is in session. Since a

department secretary is the alter ego of the President,

the acting appointee to the office must necessarily

have the Presidents confidence. Thus, by the very

nature of the office of a department secretary, the

President must appoint in an acting capacity a

person of her choice even while Congress is in

session. That person may or may not be the

permanent appointee, but practical reasons may

make it expedient that the acting appointee will also

be the permanent appointee. However, acting

appointments cannot exceed one year. The law

has incorporated this safeguard to prevent abuses,

like the use of acting appointments as a way to

circumvent confirmation by the Commission on

Appointments. (Pimentel vs. Ermita, Oct. 13, 2005).

Answer: It is evident that the position of

Commissioner of the Bureau of Customs (a

bureau head) is not one of those within the first

group of appointments where the consent of the

Commission on Appointments is required. In the

1987 Constitution deliberately excluded the position of

"heads of bureaus" from appointments that need the

consent (confirmation) of the Commission on

Appointments. (Sarmiento vs. Mison, 156 SCRA 549).

VI. It is readily apparent that under the provisions of the 1987

Constitution, there are four (4) groups of officers

whom the President shall appoint. Enumerate these

groups and determine which group/s require or

requires the concurrence of the Commission on the

Appointments.

Answer: These four (4) groups are: First, the heads

of the executive departments, ambassadors, other

public ministers and consuls, officers of the

armed forces from the rank of colonel or naval

captain, and other officers whose appointments

are vested in him in this Constitution; Second, all

other officers of the Government whose

appointments are not otherwise provided for by

law; Third, those whom the President may be

authorized by law to appoint; Fourth, officers

lower in rank whose appointments the Congress

may by law vest in the President alone. The first

group of officers is the only group which requires

the consent of the Commission on Appointments.

Appointments of such officers are initiated by

nomination and, if the nomination is confirmed by

the Commission on Appointments, the President

appoints (ibid).

VII. What are the different classifications of appointments?

Answer: Appointments may be classified into two:

first, as to its nature; and second, as to the manner

in which it is made. Under the first classification,

appointments can either be permanent or temporary

(acting). A basic distinction is that a permanent

appointee can only be removed from office for cause;

whereas a temporary appointee can be removed even

without hearing or cause. Under the second

classification, an appointment can either be regular

or ad interim. A regular appointment is one made

while Congress is in session, while an ad interim

appointment is one issued during the recess of

X.

Congress enacted several laws pertaining to ARMM. RA

6734 established the ARMM and scheduled the first

regular elections for its regional officials. R.A. No.

9054 reset elections to second Monday of September

2001, which was subsequently reset to November 26,

2001 by R.A. No. 9140. R.A. No. 9333, for the third

time, reset it to second Monday of August 2005 and

every 3 years thereafter. Pursuant to R.A. No. 9333,

the next ARMM election should have been on August

8, 2011 but Congress again enacted R.A. No. 10153

resetting it to May 2013 to coincide with the regular

national and local elections and granting the

President power to appoint OICs pending election of

new officials. Does the authority granted to the

President to appoint OICs constitutional?

Answer: During the oral arguments, the Court

identified the three options open to Congress in order

to resolve the problem on who should sit as ARMM

officials in the interim [in order to achieve

synchronization in the 2013 elections]: (1) allow the

[incumbent] elective officials in the ARMM to remain in

office in a hold over capacity until those elected in the

synchronized elections assume office; (2) hold special

elections in the ARMM, with the terms of those

elected to expire when those elected in the [2013]

synchronized elections assume office; or (3) authorize

the President to appoint OICs, [their respective terms

to last also until those elected in the 2013

synchronized elections assume office.

1st option: Holdover is unconstitutional since it

would extend the terms of office of the incumbent

ARMM officials.

2nd option: Calling special elections is

unconstitutional since COMELEC, on its own, has

no authority to order special elections.

3rd option: Grant to the President of the power to

appoint ARMM OICs in the interim is valid. At the

outset, the power to appoint is essentially

executive in nature and the limitations on or

qualifications to the exercise of this power should

be strictly construed; these limitations or

qualifications must be clearly stated in order to be

recognized.

Since the Presidents authority to appoint OICs

emanates from RA No. 10153, it falls under the third

group of officials that the President can appoint

pursuant to Section 16, Article VII of the

Constitution. Thus, the assailed law facially rests on

clear constitutional basis. (Kida vs. Senate of the

Philippines, 659 SCRA 270).

XI. President Arroyo issued Presidential Proclamation No. 420

that mandates the Adoption of a Unified, Multipurpose Identification System by all Government

Agencies in the Executive Department. This is so

despite the fact that the Supreme Court held in an En

Banc decision in 1998 ruled that Administrative Order

No. 308 (National Computerized Identification

Reference System) issued by then President Ramos

is unconstitutional because a national ID card system

requires legislation because it creates a new national

data collection and card issuance system, where

none existed before. The Supreme Court likewise

held that EO 308 as unconstitutional for it violates the

citizens right to privacy. Based on the said ruling,

questions were raised against the constitutionality of

Proclamation No. 420 on the ground that is a

usurpation of legislative power. Is the argument

correct?

Answer: Under the power of control the President,

he/she can direct all government entities, in the

exercise of their functions under existing laws, to

adopt a uniform ID data collection and ID format to

achieve savings, efficiency, reliability, compatibility,

and convenience to the public. The Presidents

constitutional power of control is self-executing and

does not need any implementing legislation. Of

course, the Presidents power of control is limited

to the Executive branch of government and does

not extend to the Judiciary or to the independent

constitutional commissions. Thus, EO 420 does

not apply to the Judiciary, or to the COMELEC which

under existing laws is also authorized to issue voters

ID cards. This only shows that EO 420 does not

establish a national ID system because legislation is

needed to establish a single ID system that is

compulsory for all branches of government. The

President has not usurped legislative power in issuing

EO 420. EO 420 is an exercise of Executive power

the Presidents constitutional power of control over

the Executive department. EO 420 is also

compliance by the President of the constitutional

duty to ensure that the laws are faithfully

executed. (Kilusang Mayo Uno vs. Ermita, et al., April

19 and June 20, 2006).

XII. Then Joseph Estrada issued EO No. 102, entitled

"Redirecting the Functions and Operations of the

Department of Health," which provided for the

changes in the roles, functions, and organizational

processes of the DOH. Under the assailed executive

order, the DOH refocused its mandate from being the

sole provider of health services to being a provider of

specific health services and technical assistance, as a

result of the devolution of basic services to local

government units.

EO No. 102 was enacted pursuant to Section 17 of

the Local Government Code, which provided for the

devolution to the local government units of basic

services and facilities, as well as specific healthrelated functions and responsibilities.

Groups and individuals assailed the validity of the

above-mentioned executive order, contending that a

law, such as EO No. 102, which effects the

reorganization of the DOH, should be enacted by

Congress in the exercise of its legislative function.

They argued that Executive Order No. 102 is void,

having been issued in excess of the Presidents

authority. They also maintain that the Office of the

President should have issued an administrative order

to carry out the streamlining, but that it failed to do so.

Are the arguments against the validity of the

executive order valid?

Answer: First, the court has already ruled in a number of

cases that the President may, by executive or

administrative order, direct the reorganization of

government entities under the Executive

Department. This is also sanctioned under the

Constitution, as well as other statutes. The law grants

the President the power to reorganize the Office of

the President in recognition of the recurring need

of every President to reorganize his or her office

"to achieve simplicity, economy and efficiency."

The Administrative Code provides that the Office of

the President consists of the Office of the

President Proper and the agencies under it. The

DOH is an agency which is under the supervision and

control of the President and, thus, part of the Office of

the President.

Consequently, the Administrative Code, granting the

President the continued authority to reorganize the

Office of the President, extends to the DOH. The

power of the President to reorganize the executive

department is likewise recognized in general

appropriations laws. Clearly, Executive Order No. 102

is well within the constitutional power of the President

to issue.

The second objection cannot be given any weight

considering that the acts of the DOH Secretary, as

an alter ego of the President, are presumed to be

the acts of the President. The members of the

Cabinet are subject at all times to the disposition of

the President since they are merely his alter egos.

Thus, their acts, performed and promulgated in the

regular course of business, are, unless disapproved

by the President, presumptively acts of the

President. Significantly, the acts of the DOH

Secretary were clearly authorized by the President,

who, thru the PCEG, issued the aforementioned

Memorandum Circular No. 62, sanctioning the

implementation of the RSP. (Tondo Medical Center

Employees Association vs. CA, 527 SCRA 746).

XIII. Then President Arroyo issued Executive Order No. 12

(E.O. 12) creating the Presidential Anti-Graft

Commission (PAGC) and vesting it with the power to

investigate or hear administrative cases or complaints

for possible graft and corruption, among others,

against presidential appointees and to submit its

report and recommendations to the President.

Thereafter, President Aquino III issued Executive

Order No. 13 (E.O. 13), abolishing the PAGC and

transferring its functions to the Office of the Deputy

Executive Secretary for Legal Affairs (ODESLA), more

particularly to its newly-established Investigative and

Adjudicatory Division (IAD). Finance Secretary

Purisima filed before the IAD-ODESLA a complaint

affidavit for grave misconduct against Prospero A.

Pichay, Jr., Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the

Local Water Utilities Administration (LWUA), as well

as the incumbent members of the LWUA Board of

Trustees. Pichay questioned the authority of the

president in abolishing the PAGC and transferring its

functions to the IAD-ODESLA. Is the argument valid?

Answer: The contention is unavailing. The President

has Continuing Authority to Reorganize the Executive

Department under E.O. 292. In the case of Buklod ng

Kawaning EIIB vs. Zamora the Court affirmed that the

President's authority to carry out a reorganization in

any branch or agency of the executive department is

an express grant by the legislature by virtue of E.O.

292. And in Domingo vs. Zamora, the Court gave the

rationale behind the President's continuing authority in

this wise: The law grants the President this power in

recognition of the recurring need of every President to

reorganize his office "to achieve simplicity, economy

and efficiency."

2010 (Truth Commission). Is it within the ambit of the

power of the President to create the above-mentioned

commission? If yes, what justification can be used in

the exercise of such power?

Clearly, the abolition of the PAGC and the transfer of

its functions to a division specially created within the

ODESLA is properly within the prerogative of the

President under his continuing "delegated legislative

authority to reorganize" his own office pursuant to

E.O. 292. (Pichay vs. Office of the Deputy Executive

Secretary for Legal Affairs Investigative and

Adjudication Division, 677 SCRA 408).

Answer: Yes. The creation of the PTC finds

justification under Section 17, Article VII of the

Constitution, imposing upon the President the duty

to ensure that the laws are faithfully executed. Section

17 reads:

Section 17. The President shall have control of all the

executive departments, bureaus, and offices. He shall

ensure that the laws be faithfully executed. The

Presidents power to conduct investigations to aid

him in ensuring the faithful execution of laws in

this case, fundamental laws on public

accountability and transparency is inherent in

the Presidents powers as the Chief Executive.

That the authority of the President to conduct

investigations and to create bodies to execute this

power is not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution or

in statutes does not mean that he is bereft of such

authority. (Biraogo vs. Truth Commission of 2010, 637

SCRA 78).

XIV. Distinguish the basic authority of the President to

reorganize the Office of the President Proper and his

general power to reorganize offices outside the Office

of the President Proper.

Answer: Generally, this authority to implement

organizational changes is limited to transferring either

an office or a function from the Office of the President

to another Department or Agency, and the other way

around. Only Section 31(1) gives the President a

virtual freehand in dealing with the internal structure

of the Office of the President Proper by allowing him

to take actions as extreme as abolition, consolidation

or merger of units, apart from the less drastic move of

transferring functions and offices from one unit to

another. Again, in Domingo vs. Zamora the Court

noted:

However, the President's power to reorganize the

Office of the President under Section 31 (2) and (3) of

EO 292 should be distinguished from his power to

reorganize the Office of the President Proper. Under

Section 31 (1) of EO 292, the President can

reorganize the Office of the President Proper by

abolishing, consolidating or merging units, or by

transferring functions from one unit to another. In

contrast, under Section 31 (2) and (3) of EO 292, the

President's power to reorganize offices outside the

Office of the President Proper but still within the Office

of the President is limited to merely transferring

functions or agencies from the Office of the President

to Departments or Agencies, and vice versa. (ibid).

XV. Can the Office of the President exercise administrative

disciplinary power over a Deputy Ombudsman and a

Special Prosecutor who belong to the constitutionallycreated Office of the Ombudsman?

Answer: The Ombudsman's administrative

disciplinary power over a Deputy Ombudsman and

Special Prosecutor is not exclusive. Section 8(2) of

the Ombudsman Act of 1989 grants the President

express power of removal over a Deputy Ombudsman

and a Special Prosecutor. While the removal of the

Ombudsman himself is also expressly provided for in

the Constitution, which is by impeachment, there is,

however, no constitutional provision similarly dealing

with the removal from office of a Deputy Ombudsman,

or a Special Prosecutor, for that matter. By enacting

Section 8(2) of R.A. 6770, Congress simply filled a

gap in the law without running afoul of any

provision in the Constitution or existing statutes.

In fact, the Constitution itself authorizes Congress to

provide for the removal of all other public officers,

including the Deputy Ombudsman and Special

Prosecutor, who are not subject to impeachment.

(Gonzales III vs. Office of the President, September

04, 2013).

XVI. When then Senator Aquino III declared his staunch

condemnation of graft and corruption with his slogan,

"Kung walang corrupt, walang mahirap." The Filipino

people, convinced of his sincerity and of his ability to

carry out this noble objective, catapulted the good

senator to the presidency. To transform his campaign

slogan into reality, President Aquino found a need for

a special body to investigate reported cases of graft

and corruption allegedly committed during the

previous administration. Thus, at the dawn of his

administration, the President signed Executive Order

No. 1 establishing the Philippine Truth Commission of

XVII.

The President, as Commander-in-Chief, is granted by

the Constitution a "sequence" of graduated powers.

What are these three powers? Enumerate it from the

most to the least benign (of a kind and gentle

disposition).

Answer: From the most to the least benign, these

are: the calling-out power, the power to suspend

the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus, and the

power to declare Martial Law (David vs. Arroyo,

May 3, 2006).

XVIII.

Three members from the International Committee of

the Red Cross (ICRC) were kidnapped in the vicinity

of the Provincial Capitol in Patikul, Sulu. The three

were purportedly inspecting a water and sanitation

project for the Sulu Provincial Jail when inspecting a

water and sanitation project for the Sulu Provincial

Jail when they were seized by three armed men who

were later confirmed to be members of the Abu

Sayyaf Group (ASG). The leader of the alleged

kidnappers was identified as Raden Abu, a former

guard at the Sulu Provincial Jail. News reports linked

Abu to Albader Parad, one of the known leaders of

the Abu Sayyaf. Thus, Governor Tan declared a state

of emergency and called upon the Armed Forces, the

police, and his own Civilian Emergency Force to

address the situation. Can Governor Tan validly

exercise emergency powers and call upon the armed

forces at his own bidding?

Answer: It is only the President, as Executive, who is

authorized to exercise emergency powers as provided

under Section 23, Article VI, of the Constitution, as

well as what became known as the calling-out powers

under Section 7, Article VII thereof. The provincial

governor does not possess the same calling-out

powers as the President. He is not endowed with

the power to call upon the armed forces at his own

bidding. In issuing the assailed proclamation,

Governor Tan exceeded his authority when he

declared a state of emergency and called upon the

Armed Forces, the police, and his own Civilian

Emergency Force. The calling-out powers

contemplated under the Constitution is exclusive

to the President. An exercise by another official,

even if he is the local chief executive, is ultra vires.

(Kulayan vs. Tan, July 03, 2012).

XIX. Sen. Biazon invited several senior officers of the AFP to

appear at a public hearing before the Senate

Committee on National Defense and Security

concerning the conduct of the 2004 elections wherein

allegations of massive cheating and the Hello Garci

tapes emerged. AFP Chief of Staff Gen. Senga issued

a Memorandum, prohibiting Gen. Gudani, Col.

Balutan and company from appearing before the

Senate Committee without Presidential approval.

Nevertheless, Gen. Gudani and Col. Balutan testified

before said Committee, prompting Gen. Senga to

order them subjected to General Court Martial

proceedings for willfully violating an order of a

superior officer. Can President Arroyo prevent military

officers from testifying at a legislative inquiry?

of a treaty; hence, it must be duly concurred in by the

Senate. Bayan Muna takes a cue from Commissioner

of Customs vs. Eastern Sea Trading. Bayan Muna

submits that the subject of the Agreement does not

fall under any of the subject-categories that are

enumerated in the Eastern Sea Trading case that may

be covered by an executive agreement. However, the

categorization of subject matters that may be covered

by international agreements mentioned in Eastern

Sea Trading is not cast in stone. The primary

consideration in the choice of the form of agreement

is the parties intent and desire to craft an international

agreement in the form they so wish to further their

respective interests. Verily, the matter of form takes

a back seat when it comes to effectiveness and

binding effect of the enforcement of a treaty or an

executive agreement, as the parties in either

international agreement each labor under the

pacta sunt servanda principle.

Answer: The President has constitutional authority to

prevent military officers from testifying at a legislative

inquiry, by virtue of her power as commander-inchief, and that as a consequence a military officer

who defies such injunction is liable under military

justice. The ability of the President to prevent military

officers from testifying before Congress does not turn

on executive privilege, but on the Chief Executives

power as commander-in-chief to control the

actions and speech of members of the armed

forces. The Presidents prerogatives as commanderin-chief are not hampered by the same limitations

as in executive privilege. (Gudani vs. Senga, 498

SCRA 671).

But over and above the foregoing considerations is

the fact thatsave for the situation and matters

contemplated in Sec. 25, Art. XVIII of the

Constitutionwhen a treaty is required, the

Constitution does not classify any subject, like

that involving political issues, to be in the form of,

and ratified as, a treaty. What the Constitution

merely prescribes is that treaties need the

concurrence of the Senate by a vote defined therein

to complete the ratification process. Indeed, an

executive agreement that does not require the

concurrence of the Senate for its ratification may

not be used to amend a treaty that, under the

Constitution, is the product of the ratifying acts of

the Executive and the Senate. The presence of a

treaty, purportedly being subject to amendment by an

executive agreement, does not obtain under the

premises. (Bayan Muna vs. Romulo, 641 SCRA 244).

XX. The International Criminal Court (ICC) under the Rome

Statute was established with "the power to exercise

its jurisdiction over persons for the most serious

crimes of international concern and shall be

complementary to the national criminal jurisdictions.

The RP, through Charge d Affaires Enrique A.

Manalo, signed the Rome Statute which, by its terms,

is "subject to ratification, acceptance or approval" by

the signatory states. Thereafter, the Philippines

entered into a Non-Surrender Agreement (Agreement)

with United States of America (USA) which aims to

protect what it refers to and defines as "persons" of

the RP and US from frivolous and harassment suits

that might be brought against them in international

tribunals.

a.

Does the Agreement, which has not been submitted

to the Senate for concurrence, contravenes and

undermines the Rome Statute and other treaties?

JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT

I.

Answer: Contrary to Bayan Munas pretense, the

Agreement does not contravene or undermine, nor

does it differ from, the Rome Statute. Far from going

against each other, one complements the other. As a

matter of fact, the principle of complementarity

underpins the creation of the ICC. As aptly pointed out

by the government and admitted by Bayan Muna, the

jurisdiction of the ICC is to "be complementary to

national criminal jurisdictions [of the signatory states]."

Nothing in the provisions of the Agreement, in relation

to the Rome Statute, tends to diminish the efficacy of

the Statute, let alone defeats the purpose of the ICC.

Lest it be overlooked, the Rome Statute contains a

proviso that enjoins the ICC from seeking the

surrender of an erring person, should the process

require the requested state to perform an act that

would violate some international agreement it has

entered into.

b.

Answer: No. Doubtless, the Framers of our

Constitution intended to create a JBC as an

innovative solution in response to the public clamor in

favor of eliminating politics in the appointment of

members of the Judiciary. To ensure judicial

independence, they adopted a holistic approach

and hoped that, in creating a JBC, the private

sector and the three branches of government

would have an active role and equal voice in the

selection of the members of the Judiciary.

Therefore, to allow the Legislature to have more

quantitative influence in the JBC by having more

than one voice speak, whether with one full vote

or one-half (1/2) a vote each, would, as one former

congressman and member of the JBC put it,

"negate the principle of equality among the three

branches of government which is enshrined in the

Constitution. It is clear, therefore, that the

Constitution mandates that the JBC be composed

of seven (7) members only. Thus, any inclusion of

another member, whether with one whole vote or half

(1/2) of it, goes against that mandate. Section 8(1),

Article VIII of the Constitution, providing Congress

with an equal voice with other members of the JBC in

recommending appointees to the Judiciary is explicit.

Any circumvention of the constitutional mandate

should not be countenanced for the Constitution is the

supreme law of the land. (Chavez vs. JBC, July 17,

2012).

Does the above-mentioned Agreement require the

concurrence of the Senate to be effective?

Answer: Under international law, there is no

difference between treaties and executive

agreements in terms of their binding effects on

the contracting states concerned, as long as the

negotiating functionaries have remained within their

powers. Authorities are, however, agreed that one is

distinct from another for accepted reasons apart from

the concurrence-requirement aspect. As has been

observed by US constitutional scholars, a treaty has

greater "dignity" than an executive agreement,

because its constitutional efficacy is beyond doubt, a

treaty having behind it the authority of the President,

the Senate, and the people; a ratified treaty, unlike an

executive agreement, takes precedence over any

prior statutory enactment.

Bayan Muna parlays the notion that the Agreement is

of dubious validity, partaking as it does of the nature

Does the first paragraph of Section 8, Article VIII of the

1987 Constitution allow more than one (1) member of

Congress to sit in the JBC? Is the practice of having

two (2) representatives from each house of Congress

with one (1) vote each sanctioned by the

Constitution?

II.

What are the requisites of a Judicial Inquiry?

Answer: In constitutional litigations, the power of

judicial review is limited by four exacting requisites,

viz: (a) there must be an actual case or

controversy; (b) petitioners must possess locus

standi; (c) the question of constitutionality must be

raised at the earliest opportunity; and (d) the issue

of constitutionality must be the lis mota of the case.

(Southern Hemisphere Engagement Network, Inc. vs.

Anti-Terrorism Council, 632 SCRA 146).

III. In the earlier mentioned case of COCOFED vs. Republic,

is the operative fact doctrine applicable because the

retroactive application to a declaration of

unconstitutionality would be unfair inasmuch as such

approach would penalize the farmers who merely

obeyed then valid laws?

Answer: The doctrine of operative fact, as an

exception to the general rule, only applies as a

matter of equity and fair play. It nullifies the

effects of an unconstitutional law by recognizing

that the existence of a statute prior to a

determination of unconstitutionality is an

operative fact and may have consequences which

cannot always be ignored. The past cannot always

be erased by a new judicial declaration. The dictates

of justice, fairness and equity do not support the claim

of the alleged farmer-owners that their ownership of

the UCPB shares should be respected.

First, said farmers or alleged claimants do not have

any legal right to own the UCPB shares

distributed to them. Second, to grant all the UCPB

shares to COCOFED and its alleged members would

be iniquitous and prejudicial to the remaining 4.6

million farmers who have not received any UCPB

shares when in fact they also made payments but did

not receive any receipt or who was not able to register

their receipts or misplaced them. Third, the

Sandiganbayan made the finding that due to

enormous operational problems and administrative

complications, the intended beneficiaries of the

UCPB shares were not able to receive the shares

due to them. Fourth, the Court also takes judicial

cognizance of the fact that a number, if not all, of

the coconut farmers who sold copra did not get

the receipts for the payment of the coconut levy

for the reason that the copra they produced were

bought by traders or middlemen who in turn sold

the same to the coconut mills. In addition, some

uninformed coconut farmers who actually got the

COCOFUND receipts, not appreciating the

importance and value of said receipts, have

already sold said receipts to non-coconut

farmers, thereby depriving them of the benefits

under the coconut levy laws. Ergo, the coconut

farmers are the ones who will not be benefited by the

distribution of the UCPB shares contrary to the policy

behind the coconut levy laws. (ibid).

IV. Under the Interim Rules Implementing the Judiciary

Reorganization Act of 1980, final decisions, xxx of the

Board of Energy (now the Energy Regulatory Board)

were made appealable to the IAC (Sec. 9). On 1987,

the President promulgated E.O. No. 172. Under Sec.

10 thereof, [a] party adversely affected by a decision,

order or ruling of the Board ... may file a petition to be

known as petition for review with the Supreme Court.

a.

Can the provision be validly enforced?

Answer: It is very patent that since Sec. 10 of E.O.

No. 172 was enacted without the advice and

concurrence of the Supreme Court, this provision

never became effective, with the result that it cannot

be deemed to have amended the Judiciary

Reorganization Act of 1980. Consequently, the

authority of the Court of Appeals to decide cases from

the Board of Energy, now ERB, remains.

b.

Is the transfer of erroneous appeals from one court to

another the proper course of action if the appeal is

brought to either Court (Supreme Court or Court of

Appeals) by the wrong procedure?

Answer: If the appeal is brought to either Court

(Supreme Court or Court of Appeals) by the wrong

procedure, the only course of action open to it is

to dismiss the appeal. There is no longer any

justification for allowing transfers of erroneous

appeals from one court to another. (Diaz vs. CA,

December 5, 1994).

V.

The GSIS seeks exemption from the payment of legal fees

imposed on GOCCs. The GSIS anchors its petition on

Section 39 of its charter, which provides that [t]axes

imposed on the GSIS tend to impair the actuarial

solvency of its funds and increase the contribution

rate necessary to sustain the benefits of this Act.

Accordingly, notwithstanding any laws to the contrary,

the GSIS, its assets, revenues including accruals

thereto, and benefits paid, shall be exempt from all

taxes, assessments, fees, charges or duties of all

kinds. xxx.

a.

What is the basis of the Supreme Court in imposing

legal fees to litigants (including the GSIS)?

Answer: Rule 141 (on Legal Fees) of the Rules of

Court was promulgated by this Court in the exercise

of its rule-making powers under Section 5(5), Article

VIII of the Constitution: Sec. 5. The Supreme Court

shall have the following powers: x x x (5) Promulgate

rules concerning the protection and enforcement of

constitutional rights, pleading, practice, and

procedure in all courts, xxx.

VI. May the legislature exempt the Government Service

Insurance System (GSIS) from legal fees imposed by

the Court on government-owned and controlled

corporations and local government units?

Answer: The separation of powers among the three

co-equal branches of our government has erected an

impregnable wall that keeps the power to

promulgate rules of pleading, practice and

procedure within the sole province of this Court.

The other branches trespass upon this prerogative if

they enact laws or issue orders that effectively repeal,

alter or modify any of the procedural rules

promulgated by this Court. Viewed from this

perspective, the claim of a legislative grant of

exemption from the payment of legal fees necessarily

fails.

Congress could not have carved out an exemption for

the GSIS from the payment of legal fees without

transgressing another equally important institutional

safeguard of the Courts independence fiscal

autonomy. Fiscal autonomy recognizes the power

and authority of the Court to levy, assess and

collect fees, including legal fees. (Re: Petition for

Recognition of the Exemption of the Government

Service Insurance System from Payment of Legal

Fees, 612 SCRA 193).

VII. Ranada filed an administrative complaint for Gross

Misconduct before the Office of the Ombudsman

against Captain Estarija. Consequently, the

Ombudsman ordered Estarijas preventive

suspension and directed him to answer the complaint.

The Ombudsman rendered a decision in the

administrative case, finding Estarija guilty of

dishonesty and grave misconduct. Estarija

seasonably filed a motion for reconsideration. He

raised the issue of constitutionality of Rep. Act No.

6770. The Ombudsman denied the motion for

reconsideration. The CA held that the attack on the

constitutionality of Rep. Act No. 6770 was

procedurally and substantially flawed. At the outset,

the CA held that the constitutional question on the

Ombudsmans power cannot be entertained because

it was not pleaded at the earliest opportunity. The CA

said that Estarija had every opportunity to raise the

same in his pleadings and during the course of the

trial. Instead, it was only after the adverse decision of

the Ombudsman that he was prompted to assail the

power of the Ombudsman in his motion for

reconsideration.

importance and immediately affects the social,

economic and moral well being of the people. The

instant petition does not allege circumstances and

issues of transcendental importance to the public

requiring their prompt and definite resolution and the

brushing aside of technicalities of procedure. Neither

is the Court convinced that the issues presented in

this petition are of such nature that would nudge the

lower courts to defer to the higher judgment of this

Court. (Moldex Realty, Inc. vs. HLURB, 525 SCRA

198).

One of the requisites for judicial review is that the

issue of constitutionality be raised at the earliest

opportunity. So when is it? Should the issue of

constitutionality of a law be raised in the

Ombudsman?

Answer: Verily, the Ombudsman has no

jurisdiction to entertain questions on the

constitutionality of a law. Thus, when Estarija

raised the issue of constitutionality of Rep. Act

No. 6770 before the Court of Appeals, which is the

competent court, the constitutional question was

raised at the earliest opportune time. (Estarija vs.

Ranada, 492 SCRA 652).

VIII. Moldex claims that since the completion of the subdivision,

it had been subsidizing and advancing the payment

for the delivery and maintenance of common facilities

including the operation of streetlights and the

payment of the corresponding electric bills. However,

Moldex decided to stop paying the electric bills for the

streetlights and advised the homeowners association

to assume this obligation.

IX. PPI and Fertiphil are private corporations incorporated

under Philippine laws. They are both engaged in the

importation and distribution of fertilizers, pesticides

and agricultural chemicals. Then President Marcos,

exercising his legislative powers, issued LOI No. 1465

which provided, among others, for the imposition of a

capital recovery component (CRC) on the domestic

sale of all grades of fertilizers in the Philippines.

The LOI provides that [t]he Administrator of the

Fertilizer Pesticide Authority to include in its fertilizer

pricing formula a capital contribution component of

not less than P10 per bag. This capital contribution

shall be collected until adequate capital is raised to

make PPI viable. Such capital contribution shall be

applied by FPA to all domestic sales of fertilizers in

the Philippines. Pursuant to the LOI, Fertiphil paid

P10 for every bag of fertilizer it sold in the domestic

market to the Fertilizer and Pesticide Authority (FPA).

FPA then remitted the amount collected to the Far

East Bank and Trust Company, the depositary bank of

PPI. After the 1986 Edsa Revolution, FPA voluntarily

stopped the imposition of the P10 levy. With the return

of democracy, Fertiphil demanded from PPI a refund

of the amounts it paid under LOI No. 1465, but PPI

refused to accede to the demand. The Court declared

LOI unconstitutional. Should Planters Products return

what it received, or should it be excused by invoking

the operative doctrine?

The association objected to Moldexs resolution and

refused to pay the electric bills. Thus, Meralco

discontinued its service, prompting the association to

apply for a preliminary injunction and preliminary

mandatory injunction with the HLURB against Moldex.

HLURB issued a Resolution granting the associations

application for injunction by citing HUDCC Resolution

No. R-562, series of 1994. HUDCC Resolution No. R562, series of 1994, particularly provides that

"subdivision owners/developers shall continue to

maintain street lights facilities and, unless otherwise

stipulated in the contract, pay the bills for electric

consumption of the subdivision street lights until the

facilities in the project are turned over to the local

government until after completion of development in

accordance with PD 957, PD 1216 and their

implementing rules and regulations." Moldex moved

for reconsideration but was rebuffed. Moldex elevated

the matter to the CA including the nullification of

HUDCC Resolution No. R-562, series of 1994, on the

ground that it is unconstitutional. The Court of

Appeals dismissed the petition on the ground that

Moldex should have raised the constitutionality of the

questioned resolution directly to the Supreme Court.

Is the action of the CA valid?

Answer: When an administrative regulation is

attacked for being unconstitutional or invalid, a

party may raise its unconstitutionality or invalidity

on every occasion that the regulation is being

enforced. For the Court to exercise its power of

judicial review, the party assailing the regulation must

show that the question of constitutionality has

been raised at the earliest opportunity. This

requisite should not be taken to mean that the

question of constitutionality must be raised

immediately after the execution of the state action

complained of. That the question of constitutionality

has not been raised before is not a valid reason for

refusing to allow it to be raised later. A contrary rule

would mean that a law, otherwise

unconstitutional, would lapse into

constitutionality by the mere failure of the proper

party to promptly file a case to challenge the

same.

It must be emphasized that the Supreme Court does

not have exclusive original jurisdiction over

petitions assailing the constitutionality of a law or

an administrative regulation. The general rule is

that the Supreme Court shall exercise only

appellate jurisdiction over cases involving the

constitutionality of a statute, treaty or regulation,

except in circumstances where the Court believes that

resolving the issue of constitutionality of a law or

regulation at the first instance is of paramount

Answer: The doctrine is inapplicable. The general

rule is that an unconstitutional law is void. It

produces no rights, imposes no duties and

affords no protection. It has no legal effect. It is, in

legal contemplation, inoperative as if it has not been

passed. Being void, Fertiphil is not required to pay the

levy. All levies paid should be refunded in accordance

with the general civil code principle against unjust

enrichment.

The court does not find anything iniquitous in ordering

PPI to refund the amounts paid by Fertiphil under LOI

No. 1465. It unduly benefited from the levy. It was

proven during the trial that the levies paid were

remitted and deposited to its bank account. Quite the

reverse, it would be inequitable and unjust not to

order a refund. To do so would unjustly enrich PPI at

the expense of Fertiphil. The Court cannot allow PPI

to profit from an unconstitutional law. Justice and

equity dictate that PPI must refund the amounts paid

by Fertiphil. (Planters Products, Inc. vs. Fertiphil

Corporation, 548 SCRA 485).

X.

Castro was charged by the Ombudsman before the RTC

with Malversation of Public Funds. Castro pleaded

NOT GUILTY when arraigned. On August 31, 2001,

Castro filed a Motion to Quash on the grounds of lack

of jurisdiction and lack of authority of the Ombudsman

to conduct the preliminary investigation and file the

Information. Citing Uy vs. Sandiganbayan, Castro

further argued that as she was a public employee with

salary grade 27, the case filed against her was

cognizable by the RTC and may be investigated and

prosecuted only by the public prosecutor, and not by

the Ombudsman whose prosecutorial power was

limited to cases cognizable by the Sandiganbayan.

The RTC sustained the prosecutorial authority of the

Ombudsman, pointing out that in Uy, upon motion for

clarification filed by the Ombudsman, the Court set

aside its earlier decision and issued a March 20, 2001

Resolution expressly recognizing the prosecutorial

and investigatory authority of the Ombudsman in

cases cognizable by the RTC. When the Information

for Malversation of Public Funds was instituted

against the Castro, can the Ombudsman file the same

in light of this SCs ruling in the First "Uy vs.

Sandiganbayan" case, which declared that the

prosecutorial powers of the Ombudsman is limited to

cases cognizable by the Sandiganbayan? Can the

clarificatory Resolution issued by the SC in the Uy vs.

Sandiganbayan case be made applicable to the

Castro, without violating the constitutional provision

on ex-post facto laws and denial of the accused to

due process?

a.

b.

Can the COMELEC cite in contempt members of the

SC?

Answer: A judicial interpretation of a statute, such

as the Ombudsman Act, constitutes part of that law

as of the date of its original passage. Such

interpretation does not create a new law but

construes a pre-existing one; it merely casts light

upon the contemporaneous legislative intent of that

law. Hence, the March 20, 2001 Resolution of the

Court in Uy interpreting the Ombudsman Act is

deemed part of the law as of the date of its effectivity

on December 7, 1989. Where no law is invalidated

nor doctrine abandoned, a judicial interpretation

of the law should be deemed incorporated at the

moment of its legislation. In the present case, the

March 20, 2001 Resolution in Uy made no declaration

of unconstitutionality of any law nor did it vacate a

doctrine long held by the Court and relied upon by the

public. Rather, it set aside an erroneous pubescent

interpretation of the Ombudsman Act. Its effect has

therefore been held by the Court to reach back to

validate investigatory and prosecutorial processes

conducted by the Ombudsman, such as the filing of

the Information against Castro. (Castro vs. Deloria,

577 SCRA 20).

XI. An Investigating Committee was created to investigate the

unauthorized release of the unpromulgated ponencia

of Justice Ruben T. Reyes in the consolidated

Limkaichong cases to determine who are responsible

for the leakage of a confidential internal document of

the En Banc. Earlier, nine Justices, not counting the

Chief Justice, would concur only in the result. Thus,

the Justices unanimously decided to withhold the

promulgation of the said unpromulgated ponencia.

The findings of the committee said that more than

substantial evidence which reasonably points to

Justice Reyes, despite his protestations of innocence,

as the source of the leak. He must, therefore, be held

liable for GRAVE MISCONDUCT. Will the subsequent

retirement of a justice from service preclude the

finding of administrative liability to which he/she is

answerable?

Answer: The subsequent retirement of a judge or

any judicial officer from the service does not

preclude the finding of any administrative liability

to which he is answerable. A case becomes moot

and academic only when there is no more actual

controversy between the parties or no useful purpose

can be served in passing upon the merits of the case.

The instant case is not moot and academic, despite

Justice Reyess retirement. Even if the most severe of

administrative sanctions may no longer be imposed,

there are other penalties which may be imposed if

one is later found guilty of the administrative offenses

charged, including the disqualification to hold any

government office and the forfeiture of benefits.

The fact that Justice Reyes was not formally charged

is of no moment. It is settled that under the doctrine

of res ipsa loquitur, the Court may impose its

authority upon erring judges whose actuations,

on their face, would show gross incompetence,

ignorance of the law or misconduct. (In Re:

Undated Letter of Mr. Louis C. Biraogo, Petitioner in

Biraogo vs. Nograles and Limkaichong, 580 SCRA

106).

XII. In its 38-page Resolution, the COMELEC First Division

basically insinuates two points as follows:

That it possesses the power to hold in contempt the

Chief Justice and some Associate Justices for their

participation and vote in decisions and orders of this

Court, which allegedly interfered with or impeded the

proceedings of the Commission; and

That it had in fact determined the "existence of

sufficient grounds to declare respondents in contempt

of [the] Commission and to 'impose the proper

penalty," were it not for the fact that the Justices were

impeachable officers who "must first be removed from

office by impeachment before any punitive measure

may be imposed against them.

Answer: The Commission has no jurisdiction to

hold the Court or any of its Members in contempt

for any, decision, order or official action they issue.

The SC has the authority to pass upon, modify or

reverse the quasi-judicial actions of the COMELEC is

UNQUESTIONED. The fact that Supreme Court

Justices are impeachable officers should not be the

ground for the COMELEC's dismissal of the contempt

charges. Rather, they cannot be held liable for

contempt, because their herein questioned Decision,

Resolution, and Order that have allegedly interfered

with, proceedings of the COMELEC were made

pursuant to their constitutional function. The SC has

the inherent authority to enforce its orders and to

hold the COMELEC's Chairman and

Commissioners in contempt when they impede,

obstruct, or degrade its proceedings or orders, or

disobey, ignore or otherwise offend its dignity.

Clearly, the COMELEC has no reciprocal

constitutional power to pass upon the actions of

this Court or its Members. Hence, the Commission

has absolutely no authority to hold them in contempt

as an incident of its inexistent power of review. While

the COMELEC is given specific powers and functions

by the Constitution, the Commission does not have

the same level and standing as the three great

branches of government. (Re: EM No. 03-010

Order of the First Division of COMELEC dated Aug.

15, 2003, A.M. No. 03-8-22 SC, Sept. 16, 2003).

ACCOUNTABILITY OF PUBLIC OFFICERS

I.

Does the system under which various forms of

Congressional Pork Barrel operate defy public

accountability as it renders Congress incapable of

checking itself or its Members?

Answer: Certain features embedded in some forms

of Congressional Pork Barrel, among others the 2013

PDAF Article, has an effect on congressional

oversight. The fact that individual legislators are given

post-enactment roles in the implementation of the

budget makes it difficult for them to become

disinterested "observers" when scrutinizing,

investigating or monitoring the implementation of the

appropriation law. To a certain extent, the conduct of

oversight would be tainted as said legislators, who are

vested with post-enactment authority, would, in effect,

be checking on activities in which they themselves

participate. Also, it must be pointed out that this very

same concept of post-enactment authorization runs

afoul of Section 14, Article VI of the 1987 Constitution

which provides that:

Sec. 14. No Senator or Member of the House of

Representatives may personally appear as counsel

before any court of justice or before the Electoral

Tribunals, or quasi-judicial and other administrative

bodies. Neither shall he, directly or indirectly, be

interested financially in any contract with, or in any

franchise or special privilege granted by the

Government, or any subdivision, agency, or

instrumentality thereof, including any governmentowned or controlled corporation, or its subsidiary,

during his term of office. He shall not intervene in any

matter before any office of the Government for his

pecuniary benefit or where he may be called upon to

act on account of his office.

Thereafter, the Secretary General transmitted the

Reyes groups complaint to Speaker Belmonte who

also directed the Committee on Rules to include it in

the Order of Business. Thereafter, the House of

Representatives simultaneously referred both

complaints to the Committee of Justice. After hearing,

the committee found both complaints sufficient in form

and substance, which complaints it considered to

have been referred to it at exactly the same time.

Meanwhile, the Rules of Procedure in Impeachment

Proceedings of the 15th Congress was published.

Ombudsman Gutierrez applied for injunctive reliefs

with the SC. A status quo order was issued by the

Court en banc.

Clearly, allowing legislators to intervene in the

various phases of project implementation a

matter before another office of government

renders them susceptible to taking undue

advantage of their own office. (ibid).

II.

What is the correct interpretation of the term "initiate in

Section 3(1), Article XI which provides that [t]he

House of Representatives shall have the exclusive

power to initiate all cases of impeachment?

Answer: From the records of the Constitutional

Commission, to the amicus curiae briefs of two former

Constitutional Commissioners, it is without a doubt

that the term "to initiate" refers to the filing of the

impeachment complaint coupled with Congress'

taking initial action of said complaint. Having

concluded that the initiation takes place by the act

of filing and referral or endorsement of the

impeachment complaint to the House Committee

on Justice or, by the filing by at least one-third of

the members of the House of Representatives

with the Secretary General of the House, the

meaning of Section 3 (5) of Article XI becomes clear.

Once an impeachment complaint has been

initiated, another impeachment complaint may not

be filed against the same official within a one year

period. (Francisco vs. The House of Representatives,

et al., Nov. 10, 2003).

III. Before the 15th Congress opened its first session the

Baraquel group filed an impeachment complaint

against Ombudsman Gutierrez, upon the

endorsement of Party-List Representatives Bagao

and Bello. A day after the opening of the 15th

Congress, the Secretary General of the House of

Representatives, transmitted the impeachment

complaint to House Speaker who directed the

Committee on Rules to include it in the Order of

Business. On another date, the Reyes group filed

another impeachment complaint against the

Ombudsman with a resolution of endorsement by

another group of Party-List Representatives. On even

date, the House of Representatives provisionally

adopted the Rules of Procedure in Impeachment

Proceedings of the 14th Congress.

a.

Is the act of simultaneously referring to the Committee

on Justice two impeachment complaints violative of

the one-year bar rule?

Answer: Contrary to the Ombudsmans asseveration,

Francisco states that the term "initiate" means to file

the complaint and take initial action on it. The

initiation starts with the filing of the complaint

which must be accompanied with an action to set

the complaint moving. It refers to the filing of the

impeachment complaint coupled with Congress

taking initial action of said complaint. The initial

action taken by the House on the complaint is the

referral of the complaint to the Committee on

Justice.

b.

Is the absence of publication in official Gazette or

newspaper of general circulation amount to violation

of due process? (Note that the Impeachment Rules

was published only on September 2, 2010 a day after

the committee ruled on the sufficiency of form of the

complaints).

Answer: No. Article XI Section 3(8) provides that

[t]he Congress shall promulgate its rules on

impeachment to effectively carry out the purpose of

this section. Since the Constitutional Commission did

not restrict "promulgation" to "publication," the

former should be understood to have been used in its

general sense. It is within the discretion of

Congress to determine on how to promulgate its

Impeachment Rules, in much the same way that the

Judiciary is permitted to determine that to promulgate

a decision means to deliver the decision to the clerk

of court for filing and publication. (Gutierrez vs. The

House of Representatives, Feb. 15, 2011).

You might also like

- Movie WatchersDocument9 pagesMovie WatchersMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Forecasting I-What Is Forecasting?Document6 pagesForecasting I-What Is Forecasting?MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

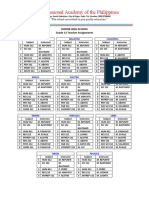

- Professional Academy of The Philippines: Senior High School Grade 12 Teacher AssignmentsDocument2 pagesProfessional Academy of The Philippines: Senior High School Grade 12 Teacher AssignmentsMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Monito MonitaDocument2 pagesMonito MonitaMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Capstone Project Sample TopicsDocument1 pageCapstone Project Sample TopicsMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Sitting ArrangementDocument5 pagesSitting ArrangementMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

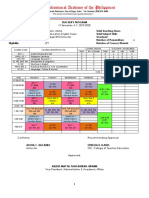

- Class Schedules For HRM 3-4Document1 pageClass Schedules For HRM 3-4MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Monito-Monita Not YetDocument1 pageMonito-Monita Not YetMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Class Schedules For HMTM - 2Document1 pageClass Schedules For HMTM - 2MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Class Schedules For HMTM - 1Document1 pageClass Schedules For HMTM - 1MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- GenED TeachersDocument9 pagesGenED TeachersMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- SHS Class Schedule 2018Document13 pagesSHS Class Schedule 2018MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Computer Laboratory UtilizationDocument2 pagesComputer Laboratory UtilizationMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Startup Science® Toolkit 1.2 - MASTERDocument71 pagesStartup Science® Toolkit 1.2 - MASTERMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Education Class Schedule 2018Document9 pagesEducation Class Schedule 2018MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Ignorantia Legis Neminem Excusat: Palafox V Province of Ilocos NorteDocument1 pageIgnorantia Legis Neminem Excusat: Palafox V Province of Ilocos NorteMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- The Lean Canvas: Problem Solution Unique Value Prop. Unfair Advantage Customer SegmentsDocument3 pagesThe Lean Canvas: Problem Solution Unique Value Prop. Unfair Advantage Customer SegmentsMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- PSITE Satorre CommercializeV2Document66 pagesPSITE Satorre CommercializeV2MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Final Students ChecklistDocument5 pagesFinal Students ChecklistMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Strategic Plan Outlin1Document1 pageStrategic Plan Outlin1MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Mis - 2Document4 pagesMis - 2MaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Strategic Plan OutlineDocument3 pagesStrategic Plan OutlineMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Contract of LeaseDocument5 pagesContract of LeaseEdvan RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Vicente ChingDocument8 pagesVicente ChingRafael Derick Evangelista IIINo ratings yet

- Board Exam ReviewerDocument3 pagesBoard Exam ReviewerMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Upside-Down Banana BreadDocument1 pageUpside-Down Banana BreadMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- 2016 Acquaintance Party Entrance FeeDocument1 page2016 Acquaintance Party Entrance FeeMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Bootcamp Invite Letter For Schools - Metro ManilaDocument4 pagesBootcamp Invite Letter For Schools - Metro ManilaMaryGraceBolambaoCuynoNo ratings yet

- Letter of IntentDocument1 pageLetter of IntentJomar Ubas LozadaNo ratings yet

- Project Proposal On Youth Socio-Economic Development Centres in TanzaniaDocument15 pagesProject Proposal On Youth Socio-Economic Development Centres in TanzaniaMwagaVumbiNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5784)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Letter To TwitterDocument2 pagesLetter To TwitterJeff RaeNo ratings yet

- Trump FilingDocument42 pagesTrump FilingAbq United100% (6)

- DNA Test Insufficient Basis for Habeas Corpus, New Trial in Rape ConvictionDocument2 pagesDNA Test Insufficient Basis for Habeas Corpus, New Trial in Rape Convictionkrystine joy sitjarNo ratings yet