Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Caraher Archaeology of and in The Contemporary World

Uploaded by

billcaraherOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Caraher Archaeology of and in The Contemporary World

Uploaded by

billcaraherCopyright:

Available Formats

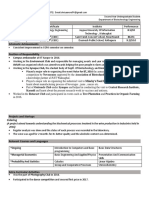

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R.

Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World

A Review Essay

William R. Caraher

University of North Dakota

Alberti, Benjamin, Andrew Meirion Jones, and Joshua Pollard, eds. Archaeology After Interpretation:

Returning Materials to Archaeological Theory. Pp. 417, figs. 74, tables 2. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek,

Calif. 2013. $94. ISBN 978-1-61132-341-2 (cloth).

Graves-Brown, Paul, Rodney Harrison, and Angela Piccini, eds. The Oxford Handbook of the

Archaeology of the Contemporary World. (Oxford Handbooks in Archaeology). Pp. 864 pages + figs. 140.

Oxford University Press, Oxford 2013. $195. ISBN 978-0-19-960200-1 (Hardback)

Martin, Andrew M. Archaeology Beyond Postmodernity: A Science of the Social (Archaeology in Society

Series). Pp. x + 247, figs. 6, table 1. AltaMira Press, Lanham, Maryland 2013. $85. ISBN 978-0-75912357-1 (cloth).

Olsen, Bjrnar, and ra Ptursdttir, eds. Ruin Memories: Materials, Aesthetics and the Archaeology of the

Recent Past (Archaeological Orientations). Pp. xviii + 492, figs. 173. Routledge, New York 2014.

$205. ISBN 978-0-415-52362-2 (cloth).

Rathje, William L., Michael Shanks, and Christopher Witmore, eds. Archaeology in the Making:

Conversations Through a Discipline. Routledge, London and New York 2013.

Fowler, Chris. The Emergent Past: A Relational Realist Archaeology of Early Bronze Age Mortuary Practices.

Pp. xii + 333, figs. 24, charts 6, tables 25, maps. 14. Oxford University Press, Oxford 2013. $135.

ISBN 978-0-19-965637-0 (cloth).

Five years ago, Rodney Harrison suggested that the modernist trope of archaeology-asexcavation no longer served the discipline well.1 Instead, Harrison suggests that we invest in the

trope of archaeology-as-surface-survey. Excavation presents archaeological practice as pealing back

superimposed layers to reveal their hidden origins. The risk of this search for origins is that it

occludes, or at least marginalizes, contributions to an unrealized present as well as opportunities to

recognize the past still present, visible, and active in our world. For Harrison, the archaeology of the

contemporary world offers a challenge to the dominant metaphor by articulating the object of

1

Harrison 2011.

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

archaeological study as the surface assemblage. This metaphor emphasizes the relationships between

objects in the assemblage and the contemporaneity of archaeological objects, while still

understanding that part of the distinction between objects depends on the relationships between the

objects and the past. While Harrisons call for a shift in metaphors is provocative for archaeological

analysis, it also provides a playful point of departure for exploring an assemblage of recent works

which have focused renewed attention on the material, agential, ontological and relational character

of archaeological assemblages.

This assemblage of books all draw on a body of scholarship outside of the discipline of

archaeology with particular attention to scholars who consider the philosophy or sociology of

science. In particular the authors reviewed in this essay drew upon Bruno Latours groundbreaking

ethnographic work on the scientific process and agency,2 and Manuel Delandas critical reflections

on assemblages and ontology.3 These scholars have offered new ways to reflect on the materiality of

objects and their place within relational networks that can include humans, animals, other objects,

institutions, methods, and archaeologists. The focus on the embedded, entangled, networked, and

symmetrical relationship between objects, humans, theories, and practices provides both a way to

consider the books in this review essay as well as a describing the techniques many of the others of

these works drew upon to analyze the past.

Bruno Latours work has served as a key inspiration for many of the authors reviewed in this

essay. Latour is a French anthropologist best known for his groundbreaking study of how science

works through his ethnographic study of a prestigious laboratory.4 While Latour developed a

sophisticated understanding of how the intersection of objects, people, technology, and institutions

impacted the history and practice of science, he did not extend his critique to include archaeology.

Andrew Martins Archaeology Beyond Postmodernity offers a vision for a Latourian archaeology. For

Martin, Latours most useful arguments center on removing the arbitrary division between culture

and nature which separated the process of scientific knowledge production from the objects of

scientific study. This division dominated the social sciences which used culture to explain the diverse

adaptations to the natural world. Science, on the other hand, draws conclusions through the

expansive and critical arrangement of data points gathered through controlled methods. Major

advances in scientific knowledge arise when scientists encounter controversies that reveal the

incompatibility of parts of their data set.

In applying Latours description of the scientific approach to archaeology, Martin offers two

main arguments for archaeology. First he suggests that the preoccupation with theory in archaeology

has limited the disciplines ability to produce compelling arguments for the past. For Martin,

archaeologists have tried to explain archaeological material with theories derived from the social

sciences and humanities ranging from the use of critical theory, which interpreted archaeological

2

3

4

Latour 1987

Delanda 2006

Latour 1987.

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

contexts as texts, to persistent flirtations with structuration of Giddens or the habitus of Bourdieu.5

Martin argued that applying externally produced theories has led archaeologists to reject evidence

that is incompatible with their theoretical models. More importantly, however, this practice

reinforced the division between the conceptual world of theory and the material world of

archaeology and presented a parallel for the division between culture and nature. Martins vision of

Latorian archaeology involves starting with the assemblage and crafting explanatory descriptions that

accommodate as many of the artifacts as possible. With this approach, the archaeologists give space

for objects to object to efforts to force them into unsuitable relationships or constructions and to

avoid projecting external understandings onto objects from the past.

The second half of the book focused on two case studies where Martin analyzes archaeological

assemblages from burial mounds associated with Hopewell culture in North America and Wessex

culture in England. Martins assemblages include more than simply portable objects found in various

stratigraphic contexts, but the location of sites, the shape of the burial mounds, and the processes

that shaped the mounds. The relationship between the various archaeological objects whether at the

scale of the landscape or individual artifacts present certain controversies that demonstrate

seemingly incongruous relationships within objects arranged through conventional archaeological

analysis. This expansive approach offered some valuable insights into these cultures, and clearly

avoided the application of a well-articulated body of theory. At the same time, Martins analysis felt a

bit artificial as he was not able to completely separate himself from theoretical traditions in

archaeological practice that assume a distinction between culture and nature. In particular, Martins

brief case studies do little to recognize the place of the archaeologist, the archaeologists tools, and

the archaeological methods in his assemblages. The relationship between pasts objects, features, and

landscapes includes our contemporary practices. The institutional, personal, and practical tools that

archaeologists use to produce these assemblages forge additional tendrils to the winding dendrites of

the archaeological discourse.

Whatever the limits of Martins work, there is no doubt that Latour is among a group of scholars

who have pushed archaeologists to become more attentive to materiality and ontology in their

understanding of archaeological assemblages and objects. Benjamin Alberti, Andrew Meirion Jones,

and Joshua Pollard recognize an archaeology after interpretation. With this provocative title, they

urge archaeologists to move away from a view of objects as representing or symbolizing society or

culture and advocate a shift toward ontological concerns which emphasize the interplay between

materiality, objects, and humans (24). This interplay considers the relational character of assemblages

and the role of this relationality in the production of ontology (236). This undermines the idea that

context provides overarching framework that allows for the interpretation of archaeological objects,

and replaces it with the study of assemblages of objects that extent to the archaeologists to produce

meaning (28). The rhizomatic relationships between objects, people, and places shape new

Giddens 1986; Bourdieu 1972.

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

archaeologies that owe more to Deleuze and Guttari (mediated through the work of Manuel

Delanda) or even Foucaults use of the term than traditional archaeological practice.6

The first and second section looks to relational ontologies and materialities as ways to offer

new interpretative strategies for archaeology. The contributions to this section range from reflection

on the role of the archaeologist at the intersection of field work and activism among mining

communities in Ecuador to critiques of the concept of the miniature in northwest Argentina.

Miniatures are only miniature versions of full sized pots if we assume a scale of measurement based

on the human form, rather than the less corporeal body of spirits. At the the south-central California

site of Chumash, traditional studies that see shades of shamanism do less to inform the rock art than

a critical examination of these images in relation to their local environment, in comparison to other

similar representations, and with a sensitivity toward the materials that the artists used. In the second

section, Chantal Conneller presented a small sample of her pathbreaking work on the relationship

between materials and forms in the upper Paleolithic with particular attention to skeuomorphs

which divorce form from material. Other contributions to this section explore how models of

change or practice have blinkered archaeologists ability to sort our complicated, longterm, and

multiple transformations. The shift from the mesolithic to the neolithic in England in fourth

millennium B.C. produced diverse assemblages that reveal multiple rates of technological change.

The third section of the work move toward understanding the relationship between the material

and social change. The authors explore the various ways in which the relationship between human

actors and objects interact. This expansive view of assemblages which include both objects and

human actors both echoes Latours view that objects can object to an ill-fitting interpretative

schema, and by extension that objects have agency in complex relational networks. The contributors

recognized parallels with animist ontologies that structure the relationship between artifacts,

landscapes, and practices and open up new perspective on the production of objects and

monuments. Joshua Pollards contribution considers the dense network of processes that emerged

through the construction of stone and earthen monuments in Avebury in the U.K. and in Polynesia.

Sarah E. Baires and colleagues explored the web of movement that shaped both the encounters with

and the production of monuments among the Woodlands groups in North America. Chris Fowler

emphasizes the role of time in how we understand the relationships throughout assemblages. Events

are objects within assemblages that play a role in producing meaning. Fowler makes a key point:

social change is not independent from the assemblage but emerges from changing relationships

between objects.

The final section of the book considers the role of representation in an archaeology that engages

materiality in a serious way. These contributions share the previous sections interest in production.

For example, Ing Marie Back Danielsson considers the practices used to produce and then to

discard Iron Age Scandinavia gold-foil images rather than simply considering their representation,

and Frederik Fahlanders careful reading of coastal rock art in Bronze Age Sweden demonstrates

how various phases of inscription relate to one another bringing time, expression, and materiality

6

Deleuze and Guttari 1980; Delanda 2006; Foucault 1969.

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

into the production of an assemblage. Andrew Conchrane likewise demonstrates a sensitivity to time

in his study of abstract imagery in the Neolithic passage times of Fourknocks, Ireland which

endured both remodeling and archaeological interventions. Sara Perrys narrative history of the

building of models and dioramas by the Institute of Archaeology at University College, London and

the role that these objects played in developing observational literacy among archaeologists as well

as revenue for the Institute.

The final contribution to the book comes from Gavin Lucas whose work on time, objects, and

archaeological methods looms large in recent reconsiderations of the archaeological practice. Lucas

approaches the ontological turn through a consideration of the ontological purification that has

traditionally divided reality into humans or things. Returning to the main focus of the book,

Lucas argues that for archaeology to do more than simply reify this division archaeologists must find

new ways of understanding the dense relational network that include a diverse range of human and

non-human objects. This shift not only marks archaeologys ongoing move toward the kind of

Latourian natural science considered by Martin, but also reflects a growing awareness of our own

networked world.

Olson and Ptursdttirs volume represents the outcome of a four-year Norwegian Research

Council grant titled Ruin Memories, and extends the ontological turn in the discipline to the

archaeology of the recent past. The introduction explores how modern ruins, memories, and

aesthetics influence what we chose to preserve and value in the modern world. Continuing the

larger trend of exploring agency in objects, Olson and Ptursdttir suggest that ruins remember their

original form in district ways, and this requires heritage preservation schemes that both preserve the

state of ruins and recognize the constant state of change. Modern ruins are neither monolithic in

meaning nor require a unified approach, but offer a rich materialism for contemporary scholarly

inquiry. This sophisticated and open-ended introduction, provides a route of entry into the

assemblage of 25 papers distributed into five sections: Things, Ethics, and Heritage; Material

Memory; Ruins, Art, Attraction; Abandonment; and Archaeologies of the Recent Past.

The second section is the most theoretical part of this book engaging both "things" and agency.

The authors here look to Bruno Latour as a point of entry into the agency of things, but they are

equally informed by Heidegger's various considerations of things. Dag T. Anderssons and Lucas D.

Introna's contributions drew particular inspiration from tool analysis from Being and Time, which

informed valuable essays in the first section. Intronas Ethics and Flesh uses Heideggers

distinction between tools present-at-hand and those ready-to-hand as a way of to understand

the absent, presence of ruins, the agency of things, and the philosophical foundations for a ethical

and symmetrical archaeology. Heidegger's recognition that things exist outside of the human world

is a foundational to understand agency in Bruno Latour's actor-network-theory. The complex

processes involved in the decay of abandoned and ruined buildings offers a vivid example of the

agency of objects. The theoretical implications of abandonment, decay, and ruination, does not

overshadow the deft the narrative touch of many of the authors. Timothy LeCains sensitive

environmental critique of the Berkeley Pitt in Butte, Montana serves dramatic example of the

5

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

anxious and blurred categories established by modernity. Caitlin DeSilveys contribution likewise

examines the limits of curation and ruination at an abandoned radar station on Orford Ness. The

discussions of agency and ethics in these conceptually demanding contributions offer suitably

complicated frameworks for understanding issues of preservation, conservation, and heritage

surrounding ruined monuments of the modern era.

The next two sections present an impressive assemblage of critical approaches to archaeology

and memory in the recent past. Many of the contributions offer the barest outlines of traditional

archaeological practice with the closest being Olsen and Witmores treatment of a Swedish POW

camp in the far north of the country. Other contributors embrace less conventional, yet still clearly

archaeological strategies for documenting objects and memories. Hein Bjerck recorded both objects

and memories in his study of his recently-deceased fathers possessions. Mats Burstrm mapped

caches of family goods from World War II in Estonia by working through memories to archaeology.

Gabriel Moshenska draws upon memories to reconstruct the ruins of bomb sites as childhood

playgrounds in blitz-wracked Britain. These articles make clear that memory and materiality are parts

of the same assemblage that archaeologists interrogate for meaning.

Other contributors take less conventional approaches toward ruins. Douglass Baileys work is a

compilation of images associated with Balkan history overwritten with texts to present complex

assemblages of memories and ruins in the shared space of the page. Elis Andreassens evocative

photo essay of Trondheim Harbor in Norway captures the tension between the static character of

the waterfront and the movement of its constituent parts. Aalsteinn sberg Sigurssons poetry

and Nkkvi Elassons photography push the reader and the viewer to look deeper into images and

texts that might not otherwise sustain scrutiny. These are not typical archaeological publications, but

push the reader or viewer to find the links both across the images and text and in the images and

text blurring the line between media and message. The poetry of Alfredo Gonzlez-Ruibals

excavation report on sites associated with the Spanish Civil War confronts the emotive impact of

sites of violence and death.

The final two sections give particular attention to marginal zones which leave their haunted scars

across the landscape: prisons, borders, frozen World War II outposts, isolated and abandoned

fishing stations, empty academic buildings. These sites require adaptation of traditional

archaeological practices to document places on the physical as well as the chronological margins of

archaeological work. Some places welcomed excavation like a storage house at an abandoned herring

station or the Skats refugee camp in Sweden, but many others demanded observation, engagement,

or careful documentation. The marginal character of these sites presents them as literally points of

contact between two or more zones of understanding. Just as ruins connect one period to the next

through their deliberate entropy, these places in the landscape are often both displaced from their

original form and desperately connected to the fabric of the present. In these examples ruins both

create and are memories that embody past and present.

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

The editors of the monumental Oxford Handbook of Archaeology of the Contemporary Past dedicated

their volume to memory of William Rathje. As the interviews in Archaeology in the Making makes clear,

Rathje tapped archaeologys potential for interrogating the contemporary world through his famous

Garbage Project. This project embraced the assemblage as the dominant method for exploring the

discard of everyday life as his study of everyday trash linked the intimate space of the household to

the world of consumption, trade, and capital. From the Garbage Project to the Oxford Handbook, the

archaeology of the contemporary world has come of age as a mature and expansive assemblage of

disciplinary practices which embodies many of the trends that shape archaeology today.

The first part makes explicitly the need for interdisciplinary perspectives on archaeology of the

contemporary world with an expected emphasis on Heidegger, Latour, Tim Ingold, and Daniel

Miller. Penny Harveys contribution introduces the ontological perspectives of contemporary

anthropological theory to the material world of archaeology; Timothy Webmoor brings sciencetechnology-studies to archaeology with the image of the knot representing the interconnected

threads of cross-disciplinary work; Albena Yaneva offers actor-network-theory as a grounded

approach to networks of humans and objects. With subtle differences, many of the crossdisciplinary perspectives demonstrate a shared appreciation of the dense links that connect humans

and objects in the contemporary world. At the same time, the broader cross-disciplinary approach

offers words of caution. For example, James Gordon Finleyson examines the interest in things in

light of contemporary philosophy and offers a preliminary definition of things that resists the

conflation of inanimate things with the broader concept of entities. The historian Tim Cole takes the

opposite tact by demonstrating how historians have engaged the material turn without the explicit

theoretical commitments that feature so prominently in archaeological work.

The second section of the work serves a glossary of crucial themes for archaeology of the

contemporary world, but speak significantly to the discipline of archaeology more broadly. Issues

like time, ruins, memory, heritage, modernism, authenticity, and scale remain crucial

considerations for archaeologists in any period. For the archaeology of the contemporary world,

notions of time, ruins, memory, and heritage take on particular significance as scholars negotiate the

interplay between the past and the present with as much attention the latter as the former. If

traditional archaeological practice relies on the idea that the excavator peels away the present to

reveal the past, the notion of an archaeology of the contemporary world challenges the discipline to

reflect on the relationship between practice and time. As the Olson and Ptursdttir volume

developed at greater length modern ruins, memories, and heritage require attentiveness to

contemporary networks binding the archaeologist to the site, to aesthetic and practical judgements,

and to the communities impacted by archaeological work. The potential for archaeology to

contribute to pressing contemporary issues like homelessness, conflicts, waste, and disasters is

presented as intrinsic in the larger project of contemporary archaeology.

The final three sections feature case studies that explore mobilities, space and place; media and

mutabilities; and things and connectivities. The thematic organization of these final 21 contributions

is almost arbitrary as key ideas cut across articles in each section. Navigating the archaeology of the

contemporary and recent past drew particular attention to the location of the archaeologists in

7

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

relation to his or her work. John Schofields research into the gritty area called the Gut on Malta

required him to position himself as a safe, but knowledgable outsider. Um Z. Rizvis work on the

gendered space of military checkpoints explicitly relied on the authors experience in the Iraq war as

well as her gender, the fractured state, and her understanding of Iraqs archaeological heritage. Pierre

Lemonniers autoanthropology of the automobile (authors pun intended) recognized that the

archaeologist and anthropologist of the modern world cannot escape from the history, materiality,

and archaeology of these objects, and offers a useful pendant to Peter Merrimans archaeology of

roads and motor cars. Similar attention to technologies and practice emerge from the contributions

that explore the archaeology of media ranging from drawing and film to more explicitly

performative acts such as rioting in England and Estonia or gathering at the Burning Man festival in

Nevada. Sefryn Penrose archaeology of the postindustrial body offers a compelling view of the

archaeologist at work, not in some exotic locale, but in an ergonomic chair at a laptop computer in

an office.

A book of this length and diversity rewards more attention than a review essay can give. This

expansive assemblage of articles encourages the kind of reading that moves across the various

sections and contributions. Archaeology for social change, the archaeology of late capitalism,

archaeology and design, and the complex politics of heritage recur throughout these works. The

issues locate the archaeology of the contemporary world less as a modern coda to traditional

archaeological practice, and more as a distinct position from which to offer critique of the entire

discipline.

These contemporary, disciplinary concern permeate the collection of conversations that

moderated by Bill Rathe, Michael Shanks and Christopher Witmore in Archaeology in the Making:

Conversations though a Discipline. Like the Oxford Handbook, this work is best seen as a compelling

assemblage of engagements with the leading lights in the field of archaeology. As a volume, it lacks

the structure of a neatly stratified deposit, but sheds considerable light on the complex assemblage

of disciplinary knowledge. The various interviews are grouped into three categories: the

archaeological imagination, the working of archaeology, and politics, but many of the wide ranging

interviews could as easily appeared in any of the sections of the book. Each interview is

supplemented with explanatory notes often provided by the interviewee. The interviewers generally

start with general questions about the scholars background and then use that as a point of

departure for wider ranging questions concerning field work, intellectual influences, involvement in

various movements in the field, and institutional experiences.

The first section of the book offers some remarkable insights into the such key movements in

archaeology as Binfords processualism, Schiffers behavioral archaeology, and Renfrews interest in

language and archaeology. These are set against Ian Hodders expansive comments on the

relationship between humans and objects, Alison Wylies probing of the intellectual foundation of

archaeological knowledge, and Patty Jo Watsons frank assessment of her career trajectory and the

challenges of being a woman in the field during the mid-20th century. These interviews were not

focused essays or explicit contributions to a history of the discipline, and the editors resisted the

8

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

temptation to distill them into tidy and digestible statements. Instead, the editors drew attention to

the expansive Greek concept of ta pragmata in the interview and how the authors engaged the deeds,

encounters, and obligation that shaped their engagement with the material world.

The second group of interviews focused on the widest possible understanding of field work, but

like the previous, range widely. George Cowgills explained his flirtation with physics prior to his

turn to archaeology, and how his experience in the hard sciences paralleled the tension between the

micro and macro in archaeology. Adrian and Mary Praetzelliss discussed the practical realities and

remarkable opportunities of (Cultural Resource Management) CRM with particular attention to their

work in an African-American neighborhood in Oakland. Kristian Kristiansen globalized the

discussion through his experiences in heritage and academic institutions in Scandinavia. Alain

Schnapps detailed his experiences in establishing institutional foundations for a sophisticated

transnational archaeology in France. Susan Alcock and John Cherrys discuss the political challenges

of working in Greece and the opportunities associated with working in Armenia. The editors framed

these interview with the idea of tekne and craftwork necessary to negotiate institutions, funding

agencies, and traditional archaeological practice.

The last group of interviews in the book explore ta politika, with its expansive definition of

public matters as well as formal politics explores the connections between archaeological work and

political, ideological, and ethical realities. Ruth Tringham describes the cold war political realities that

shaped access to materials and research early in her career. Victor Buchli explored the political

decision to hide his homosexuality from his ethnographic informants in Russia. Mark Leone

described his commitments to lobbying and political activism to promote archaeology at the local

and national levels. Lynne Meskell expresses her concern for the political stakes involved in

archaeology and conservation in South Africa. These interviews have firm connections with those

throughout the book and emphasize the situated character of all archaeological research.

The book is concluded with a sketch a disciplinary ecology across seven common threads

ranging from politics, institutions, memory practices, knowledge designs, affiliations with other

fields and practices to more complex concepts associated with the common past (and futures) of the

world, the perpetuating and gains of competence, and the work involved in manifesting material

pasts. The interviews throughout the book demonstrate that these intellectual threads are entangled

with personal narratives, institutional limits and opportunities, professional and personal

relationships, and economic realities. The ecology presented by the editors emerges from an

assemblage of conversations that enrich one another and the disciplinary contributions of the

participants and locates the archaeologist at the center of archaeological assemblages.

The interviews of Rathje, Shanks, and Witmore emphasized the archaeologists place within the

archaeological assemblage and situated disciplinary knowledge within a robust ecology of practice,

institutions, and knowledge. Chris Fowlers The Emergent Past: A Relationist, Realist Archaeology of Early

Bronze Age Mortuary Practices locates the archaeologists in his ontological critiques of archaeological

objects. He approaches the assemblage of Early Bronze Age objects in Britain as an artifact of both

archaeological practice and past events.

9

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

The second chapter of his book is perhaps the most useful for scholars who do not work

specifically on Early Bronze Age Britain. Fowler offers a thorough critique of many of the key

theories for understanding the relationship between objects and people. He argues for a practice

grounded in relational realism which is based, in part, on Latours concept of circulating reference.

This concept recognizes the reality of the assemblages as dynamic sets of relationships that

constantly refigure themselves. Archaeologists, then, do not study an assemblage as a static object,

but actively participate in the reconfiguration of that assemblage through practices, tools, and

theories. These assemblages constitute past realities which are as entangled in the present as they are

dependent upon the residues of past relationships. For Fowler, recognizing these assemblages as real

and not simply arbitrary representations of a vanished past is crucial and constitutes the realism in

his concept of relational realism.

Chapter 4 to 6 focus on the archaeology of mortuary practices in Chalcolithic and Early Bronze

Age Britain. Chapter four provides the most extensive discussion of grave goods and burial types

interlaced with regional maps and tables. Chapter five expands the assemblage associated with these

burials to the larger landscape with attention to settlements, natural features, and other monuments.

Chapter six presents a rigorous and transparent narrative of burial practices the Early Bronze Age

Britain based upon his careful descriptions in the chapters four and five. Fowler characterizes this

survey using Tim Ingolds term inversions to describe the various relations that make his analysis

of Early Bronze Age burial practices possible. Fowlers stresses that these inversions are not fixed

and depend, in part, on his own location in the field, the methods and tools used to analyze these

assemblages, and, perhaps most importantly, the relationship between past objects and events. For

Fowler all these relations are real and are grounded in archaeological assemblages present in both the

past and the present.

Like most recent efforts to explore the nature of assemblages in archaeology, Fowler insists that

the relations present throughout assemblages constitute the basis for archaeological analysis. The

tensions and attractions between the various parts of these assemblages which include the

archaeologist as well as objects from the past presents a particular shape. Some aspects of this shape

are contingent upon technologies, the extent of our evidence, and practice, but other parts of the

assemblage demonstrate remarkable stability and will persist for millennia. The intersection of

various forces within the assemblage produced his book which will subsequently influence future

efforts to describe Early Bronze Age practices.

For Fowler, it is impossible to escape the legacies of archaeological analysis and interpretation

because they shaped processes of artifact recovery, curation, and publication upon which his work

and much archaeological work continues to depend. In recognizing this, he makes the work of

Rathje, Shanks, and Witmore even more important for any archaeologist who seeks to recognize the

complex assemblages that constitute our field.

It is always tempting to view the latest theoretical or conceptual move in archaeological thought

as a revelatory moment that will empower social change, produce new knowledge, and open new

vistas for inquiry. In fact, it is difficult to escape the positive, critical energy in these volumes and not

10

Archaeology in and of the Contemporary World: A Review Essay. William R. Caraher

Do not cite without authors permission.

recognize that these ideas are more than just the incestuous flirtations of the theory crowd. These

scholars attention to objects and materiality fall neatly inside the traditional purview of archaeology.

Renewed attention to the assemblage as a meaningful concept for articulating the networks of

objects, landscapes, practices, and individuals that make archaeological knowledge promotes a

reflective and self-aware discipline, but also remains literally and figuratively grounded in objects,

materials, and past practices. Whatever the degree to which we embrace the ontological turn, this

trend in archaeological analysis reinforces the place of the object or artifact as the starting point of

archaeological inquiry.

It is important to emphasize that the way of thinking presented across these books does little to

challenge existing archaeological field practices and procedures, but they provide a way to reframe

how we articulate the relationship between field work, tools, and fragments of the past. The

importance of this reframing today is that the subject of archaeological analysis is expanding

chronologically to include the contemporary world, but the tools that archaeologists use to

document the past have undergone significant technological change in the last three decades.

Harrisons suggestion that archaeologists adopt the assemblage as the key metaphor for

archaeological work at the assemblage recognizes the relationship between past and present objects

as crucial for the production of archaeological knowledge. The books surveyed in this review essay

provide a powerful set of intellectual tools for this approach.

11

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Lessons From The Bakken Oil PatchDocument20 pagesLessons From The Bakken Oil PatchbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- The Bakken: An Archaeology of An Industrial LandscapeDocument24 pagesThe Bakken: An Archaeology of An Industrial LandscapebillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Slow ArchaeologyDocument14 pagesSlow Archaeologybillcaraher100% (1)

- Slow ArchaeologyDocument11 pagesSlow ArchaeologybillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Slow Archaeology, Version 4Document12 pagesSlow Archaeology, Version 4billcaraherNo ratings yet

- Slow Archaeology: Technology, Efficiency, and Archaeological WorkDocument16 pagesSlow Archaeology: Technology, Efficiency, and Archaeological WorkbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- The Archive (Volume 6)Document548 pagesThe Archive (Volume 6)billcaraherNo ratings yet

- An Epilogue To The Tourist Guide To The Bakken Oil PatchDocument10 pagesAn Epilogue To The Tourist Guide To The Bakken Oil PatchbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Ontology, World Archaeology, and The Recent PastDocument15 pagesOntology, World Archaeology, and The Recent PastbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- North Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in The Bakken Oil FieldsDocument31 pagesNorth Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in The Bakken Oil FieldsbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Review of Butrint 4Document3 pagesReview of Butrint 4billcaraherNo ratings yet

- Joel Jonientz, "How To Draw... Punk Archaeology"Document11 pagesJoel Jonientz, "How To Draw... Punk Archaeology"billcaraherNo ratings yet

- The University in The Service of SocietyDocument33 pagesThe University in The Service of SocietybillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Man Camp Dialogues Study GuideDocument1 pageMan Camp Dialogues Study GuidebillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Review of Michael Dixon's Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Corinth, 138-196 BCDocument2 pagesReview of Michael Dixon's Late Classical and Early Hellenistic Corinth, 138-196 BCbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The NDQ Special Volume On SlowDocument5 pagesIntroduction To The NDQ Special Volume On SlowbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Visions of Substance: 3D Imaging in Mediterranean ArchaeologyDocument125 pagesVisions of Substance: 3D Imaging in Mediterranean Archaeologybillcaraher100% (1)

- One Hundred Years of PeaceDocument28 pagesOne Hundred Years of PeacebillcaraherNo ratings yet

- The Archive (Volume 5)Document733 pagesThe Archive (Volume 5)billcaraherNo ratings yet

- North Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in The Bakken Oil FieldsDocument59 pagesNorth Dakota Man Camp Project: The Archaeology of Home in The Bakken Oil FieldsbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Punk ArchaeologyDocument234 pagesPunk Archaeologybillcaraher100% (3)

- Slow Archaeology Version 2Document14 pagesSlow Archaeology Version 2billcaraherNo ratings yet

- PKAP IntroductionDocument23 pagesPKAP IntroductionbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Artifact and Assemblage at Polis-Chrysochous On CyprusDocument73 pagesArtifact and Assemblage at Polis-Chrysochous On CyprusbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Slow ArchaeologyDocument12 pagesSlow ArchaeologybillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Settlement On Cyprus During The 7th and 8th CenturiesDocument17 pagesSettlement On Cyprus During The 7th and 8th CenturiesbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Imperial Surplus and Local Tastes: A Comparative Study of Mediterranean Connectivity and TradeDocument29 pagesImperial Surplus and Local Tastes: A Comparative Study of Mediterranean Connectivity and TradebillcaraherNo ratings yet

- Settlement On Cyprus During The 7th and 8th CenturiesDocument26 pagesSettlement On Cyprus During The 7th and 8th CenturiesbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- The Archaeology of Man-Camps: Contingency, Periphery, and Late CapitalismDocument13 pagesThe Archaeology of Man-Camps: Contingency, Periphery, and Late CapitalismbillcaraherNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Bus210 Week5 Reading1Document33 pagesBus210 Week5 Reading1eadyden330% (1)

- SINGLE OPTION CORRECT ACCELERATIONDocument5 pagesSINGLE OPTION CORRECT ACCELERATIONShiva Ram Prasad PulagamNo ratings yet

- Affine CipherDocument3 pagesAffine CipheramitpandaNo ratings yet

- Chrome FlagsDocument12 pagesChrome Flagsmeraj1210% (1)

- Differential Aptitude TestsDocument2 pagesDifferential Aptitude Testsiqrarifat50% (4)

- DN 6720 PDFDocument12 pagesDN 6720 PDFChandan JhaNo ratings yet

- ASVAB Arithmetic Reasoning Practice Test 1Document7 pagesASVAB Arithmetic Reasoning Practice Test 1ASVABTestBank100% (2)

- Newsletter April.Document4 pagesNewsletter April.J_Hevicon4246No ratings yet

- Chemistry An Introduction To General Organic and Biological Chemistry Timberlake 12th Edition Test BankDocument12 pagesChemistry An Introduction To General Organic and Biological Chemistry Timberlake 12th Edition Test Banklaceydukeqtgxfmjkod100% (46)

- Validating and Using The Career Beliefs Inventory: Johns Hopkins UniversityDocument12 pagesValidating and Using The Career Beliefs Inventory: Johns Hopkins Universityyinyang_trNo ratings yet

- Cost-effective laboratory thermostats from -25 to 100°CDocument6 pagesCost-effective laboratory thermostats from -25 to 100°CCynthia MahlNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Knowledge, Attitude Andpractice Toward Sexually Transmitteddiseases in Boditi High School StudentsDocument56 pagesAssessment of Knowledge, Attitude Andpractice Toward Sexually Transmitteddiseases in Boditi High School StudentsMinlik-alew Dejenie88% (8)

- A Report On T&D by IbrahimDocument17 pagesA Report On T&D by IbrahimMohammed IbrahimNo ratings yet

- Sap CRM Web - UiDocument7 pagesSap CRM Web - UiNaresh BitlaNo ratings yet

- Inbound Delivery ProcessDocument5 pagesInbound Delivery ProcessDar Pinsor50% (2)

- Cambridge C1 Advanced Exam Overview PDFDocument1 pageCambridge C1 Advanced Exam Overview PDFrita44No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan-Brainstorming Session For The Group Occupational Report-Jmeck Wfed495c-2 V4a7Document2 pagesLesson Plan-Brainstorming Session For The Group Occupational Report-Jmeck Wfed495c-2 V4a7api-312884329No ratings yet

- Developing and Validating a Food Chain Lesson PlanDocument11 pagesDeveloping and Validating a Food Chain Lesson PlanCassandra Nichie AgustinNo ratings yet

- List of indexed conferences from Sumatera UniversityDocument7 pagesList of indexed conferences from Sumatera UniversityRizky FernandaNo ratings yet

- FeminismDocument8 pagesFeminismismailjuttNo ratings yet

- Components of GMP - Pharma UptodayDocument3 pagesComponents of GMP - Pharma UptodaySathish VemulaNo ratings yet

- Installing OpenSceneGraphDocument9 pagesInstalling OpenSceneGraphfer89chopNo ratings yet

- AufEx4 02 02Document28 pagesAufEx4 02 02BSED SCIENCE 1ANo ratings yet

- Shriya Arora: Educational QualificationsDocument2 pagesShriya Arora: Educational QualificationsInderpreet singhNo ratings yet

- Chapter 1Document9 pagesChapter 1Ibrahim A. MistrahNo ratings yet

- SK08A Addressable Loop-Powered Siren Installation Sheet (Multilingual) R2.0Document12 pagesSK08A Addressable Loop-Powered Siren Installation Sheet (Multilingual) R2.0123vb123No ratings yet

- Summary and RecommendationsDocument68 pagesSummary and Recommendationssivabharathamurthy100% (2)

- Eps-07 Eng PDFDocument54 pagesEps-07 Eng PDFPrashant PatilNo ratings yet

- Leader 2Document13 pagesLeader 2Abid100% (1)