Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Basic and Advanced Cardiac Life Support: What's New?

Uploaded by

frakturhepatikaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Basic and Advanced Cardiac Life Support: What's New?

Uploaded by

frakturhepatikaCopyright:

Available Formats

Child development

Emergency

care

Hugh JM Grantham

Ramanathan

Narendranathan

Basic and advanced

cardiac life support

Whats new?

Background

Australian Resuscitation Council guidelines on basic and

advanced life support are amended periodically. These

changes are informed by recent evidence on best practice

in resuscitation medicine. In December 2010, the latest

guidelines were released for implementation in 2011.

Objective

This article outlines the key messages from the latest

Australian Resuscitation Council guidelines on basic and

advanced life support.

Discussion

The latest Australian Resuscitation Council guidelines on

basic and advanced life support emphasise the importance

of early recognition of deterioration before cardiac arrest.

Once resuscitation commences, there is a focus on

early defibrillation and early chest compressions with a

simplification of drug treatment. Postresuscitation phase

changes emphasise early intervention to re-establish coronary

artery patency and therapeutic hypothermia.

Keywords

emergencies; heart failure

386 reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 41, No. 6, june 2012

Cardiac life support is a relatively young field of medical expertise

with cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) as we know it only

being described in 1960.1 As new evidence on best practice in

resuscitation medicine comes to light, the recommendations for

resuscitation and life support evolve and change.

Every 5 years the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation

(ILCOR) assesses the latest evidence evaluated by an international body

of experts interested in resuscitation and issues updated guidelines.2

The Australian Resuscitation Council (ARC), in conjunction with the

New Zealand Resuscitation Council, contributes to this process on

behalf of the Pacific region. In December 2010, the latest guidelines

were released in Australia for implementation in 20113 (Figure 1, 2).

The key messages from the new guidelines are about recognising

the importance of compressions, simplifying drug regimens and

emphasising the importance of postresuscitation care.

Importance of compressions

Continuous compressions allow a build-up of pressure in the aorta,

which in turn maintains flow to both the myocardium and the brain.

Whenever there is a break in compressions to allow ventilation or to

perform some other manoeuvre, the pressure within the aorta drops.

Guidelines have attempted to reflect this by reducing or eliminating

as much as possible any gaps in compression. Over the years,

compression to ventilation ratios have changed from five compressions

to one ventilation, to 30 compressions to two ventilations. In the new

ARC basic life support guidelines, the value of providing ventilation at

all is considered discretionary.4

The guidelines support starting compressions on any person who

is not responsive and not breathing normally.4 The description not

breathing normally means that, even if the person still has agonal

respiratory effort, compressions should be started quickly. The rescuer

then should consider two ventilations for every 30 compressions, if

they are willing and able. This change in policy from ventilation first

recognises that compression only cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)

is significantly better than no CPR.4 Some authors recommend advising

bystanders and first responders to use compression only CPR in the

first instance on the basis that this will increase the percentage of

patients receiving CPR.5 In one South Australian study, under half of the

patients in cardiac arrest received CPR, which represents a significant

missed opportunity.6

Figure 1. Australian Resuscitation Council basic life support algorithm

reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 41, No. 6, june 2012 387

FOCUS Basic and advanced cardiac life support whats new?

Figure 2. Australian Resuscitation Council advanced life support for adults algorithm

388 reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 41, No. 6, june 2012

Basic and advanced cardiac life support whats new? FOCUS

Importantly, in the basic life support guidelines all reference to

checking a pulse has been dropped on the basis that patients who

are not responsive and not breathing normally are highly likely to

be in arrest and will not be harmed by compressions if these are

commenced unnecessarily.4

The new advanced life support guidelines also support continuous

CPR, with a change to the recommendations surrounding charging

and discharging a manual defibrillator. The new recommended

procedure when using a manual defibrillator with pads for contact is

to charge the defibrillator while compressions continue and only stop

compressions when it is fully charged and ready to defibrillate.7 Once

the defibrillation has occurred, compressions should be commenced

straight away with no pause to assess the outcome of the shock.

This is a significant departure from past practice and has been

recommended in light of evidence about the safety of compression

when using the newer biphasic external defibrillators with conformal,

adhesive, pregelled electrodes. However, care should still be taken

to prevent defibrillation while performing compressions until further

research evidence is available, particularly when using older model

defibrillators.8 Using the technique outlined in the new guidelines,7

it is possible to assess a rhythm and deliver a shock with a break in

compressions of only about 8 seconds. Unfortunately, this technique

cannot be used with semiautomatic defibrillators, which are more

commonly available in a general practice and public areas, because

they require a static period in which to identify a shockable rhythm

(ventricular fibrillation or ventricular tachycardia) and then charge.

Simplifying drug regimens in cardiac

arrest

The trend in drug therapy for cardiac arrest is toward simplification

of the process and treating the patient on a standard protocol. We

are now effectively down to two drugs adrenaline and amiodarone

in addition to electricity and oxygen.

The new ARC advanced life support guidelines recommend that

1 mg of adrenaline be given intravenously every second cycle of

CPR.7 As CPR is delivered for 2 minutes every cycle, this means

that adrenaline is given every four-and-a-bit minutes (compared

to every 3 minutes in the previous guidelines). In patients with a

shockable rythmn (ventricular fibrillation and pulseless ventricular

tachycardia), the first action would be to defibrillate as soon as

possible followed by 2 minutes of CPR and the second defibrillation,

after which adrenaline should be started and repeated every second

cycle. In a pulseless electrical activity arrest or asystolic arrest the

adrenaline should be started as soon as possible and again repeated

every second cycle. The dose of adrenaline should be given with a

significant fluid push (100 mL) behind it.

Amiodarone is the only other drug used in a routine cardiac arrest

and 300 mg is given to patients in a shockable rhythm (ventricular

fibrillation and pulseless ventricular tachycardia) after the third

defibrillation. In normal practice, there is no need for any repeat doses

as this dose is thought to provide an adequate anti-arrhythmic effect.9

Atropine, which used to be recommended for asystole, is no

longer part of the cardiac arrest algorithm although it is still used

to treat bradycardia in a nonarrested patient.

Postresuscitation care

The third key message from the new ARC advanced life support

guidelines is the importance of appropriate postresuscitation care.9

Postresuscitation, consider the following three areas early:

Attention to detail. This involves addressing contributing factors

to the arrest, eg. by normalising electrolytes and blood glucose

Removal of the underlying cause of the cardiac arrest with

either angioplasty or, in remote areas, by thrombolysis. Systems

now exist for rapid access to angioplasty in most large centres

with thrombolysis being supported in those areas where a

patient cannot be transported to an angioplasty suite within

6090 minutes

Cooling of the postresuscitation patient, aiming for a period of

mild hypothermia for 24 hours following return of circulation

for most patients. Hypothermia can be achieved with a large

volume of cold saline or more specialised cooling devices.

Preliminary studies in both Australia and Europe have shown

a survival benefit from cooling and this has now become the

standard of care.10 Trials of commencing this cooling in the

prehospital phase are under way in Victoria, with Western

Australia and South Australia due to join the trial in early

2012.11

Outcomes and prevention

Return of circulation rates in the order of 25% for all witnessed

out-of-hospital cardiac arrests, and 45% if the patient was in

ventricular fibrillation (VF) or ventricular tachycardia (VT), are

becoming the expected standard.10 An overall hospital discharge

rate for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest of 7.6% has been reported.10

Of course the best results from cardiac arrests are when the

arrest has been averted by early detection and early intervention.12

The National Safety and Quality Council has identified the

recognition and response to the deteriorating patient as one of

its key initiatives in improving quality and safety. As standardised

systems of early recognition and response become widespread

throughout the health system it should be hoped that fewer

patients go on to suffer a cardiac arrest.

Summary

The latest ARC guidelines on basic and advanced life support

emphasise the importance of early recognition of deterioration for

patients already within the system, early defibrillation and early

chest compressions with a simplification of drug treatment and

appropriate postresuscitation care.

None of the new developments are particularly surprising,

as they represent the continuation of trends that have been

developing over recent years.

reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 41, No. 6, june 2012 389

FOCUS Basic and advanced cardiac life support whats new?

Authors

Hugh JM Grantham ASM, MBBS, FRACGP, is Professor of

Paramedics, Flinders University and Senior Medical Practitioner, South

Australian Ambulance Service, Adelaide, South Australia. hugh.grantham@flinders.edu.au

Ramanathan Narendranathan MBBS, DCH, PhD, FRACGP, FACTM,

is a general practitioner, Melbourne, RACGP representative at the

Australian Resuscitation Council and former staff specialist in emergency medicine, Lyell McEwen Health Service, South Australia.

Conflict of interest: none declared.

References

1. Whitcomb JJ, Blackman VS. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation: how far have

we come? Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2007;26:16.

2. Nolan JP, Hazinski MF, Billi JE, et al. Part 1: Executive summary: 2010

International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency

Cardiovascular Care Science With Treatment Recommendations.

Resuscitation 2010;81(Suppl 1):e125.

3. Leman P, Jacobs I. What is new in the Australasian Adult Resuscitation

Guidelines for 2010? Emerg Med Australas 2011;23: 2379.

4. Australian Resuscitation Council. Guideline eight: cardiopulmonary

resuscitation. 2010. Available at www.resus.org.au/policy/guidelines/

section_8/cardiopulmonary_resuscitation.htm.

5. Kellum MJ. Compression-only cardiopulmonary resuscitation for bystanders and first responders. Curr Opin Crit Care 2007;13:26872.

6. Zeitz K, Grantham H, Elliot R, Zeitz C. Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest-review

of demographics in South Australia to inform decisions about the provision of automatic external defibrillators within the community. Prehosp

Disaster Med 2010;25:5216.

7. Australian Resuscitation Council. Advanced life support. Melbourne, 2011.

Available at www.resus.org.au/files/summary_of_major_changes_to_

als_guidelinesmar2011.pdf.

8. Lloyd MS, Heeke B, Walter PF, Langberg JJ. Hands-on defibrillation: an analysis of electrical current flow through rescuers in direct

contact with patients during biphasic external defibrillation. Circulation

2008;117:25104.

9. Deakin CD, Morrison LJ, Morley PT, et al. Part 8: Advanced life support:

2010 International Consensus on Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation

and Emergency Cardiovascular Care Science with Treatment

Recommendations. Resuscitation 2010;81(Suppl 1):e93174.

10. Nolan JP. Optimizing outcome after cardiac arrest. Curr Opin Crit Care

2011;17:5206.

11. Deasy C, Bernard S, Cameron P, et al. Design of the RINSE Trial: the Rapid

Infusion of cold Normal Saline by paramedics during CPR. BMC Emerg

Med 2011;11:17.

12. Nolan JP, Omato JP, Parr MJA, et al. Resuscitation highlights in 2011.

Resuscitation 2012;83:16.

390 reprinted from Australian Family Physician Vol. 41, No. 6, june 2012

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Advanced Life Support-RESSU CouncilDocument30 pagesAdvanced Life Support-RESSU CouncilGigel DumitruNo ratings yet

- Guidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportDocument34 pagesGuidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportParvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- Guidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportDocument35 pagesGuidelines Adult Advanced Life SupportindahNo ratings yet

- Basic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS)Document7 pagesBasic Life Support (BLS) and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS)Rizki YuliantoNo ratings yet

- Resusitasi AnastesiDocument15 pagesResusitasi AnastesiFannia ReynathaNo ratings yet

- RACE 2017 MegacodeDocument33 pagesRACE 2017 MegacodemickeyNo ratings yet

- ACLS DrugsDocument4 pagesACLS DrugsEduard Espeso Chiong-Gandul Jr.No ratings yet

- ANZCOR Guideline 11.2 - Protocols For Adult Advanced Life SupportDocument8 pagesANZCOR Guideline 11.2 - Protocols For Adult Advanced Life SupportMario Colville SolarNo ratings yet

- Recommendations)Document10 pagesRecommendations)Niko NeznanovicNo ratings yet

- Adult Advanced Life SupportDocument14 pagesAdult Advanced Life SupportAnonymous TT7aEIjhuhNo ratings yet

- Managing Atrial Fibrillation 2015Document8 pagesManaging Atrial Fibrillation 2015Mayra Alejandra Prada SerranoNo ratings yet

- Adult Advanced Life Support: Resuscitation Council (UK)Document23 pagesAdult Advanced Life Support: Resuscitation Council (UK)Masuma SarkerNo ratings yet

- CAB-CPR UpdateDocument15 pagesCAB-CPR Updatedragon66No ratings yet

- Mona Adel, MD, Macc A.Professor of Cardiology Cardiology Consultant Elite Medical CenterDocument34 pagesMona Adel, MD, Macc A.Professor of Cardiology Cardiology Consultant Elite Medical CenterOnon EssayedNo ratings yet

- ACLSDocument39 pagesACLSJason LiandoNo ratings yet

- 2020 AHA Guidelines For CPR and ECC PrintableDocument21 pages2020 AHA Guidelines For CPR and ECC PrintableSajal Saha100% (1)

- Basic Life Support and Advanced Cardiovascular Life SupportDocument90 pagesBasic Life Support and Advanced Cardiovascular Life SupportRakhshanda khan100% (1)

- BLS & AclsDocument13 pagesBLS & AclsadamNo ratings yet

- Bls - Acls Update American Heart Association 2020: Ns. Anastasia Hardyati., Mkep., Sp. KMBDocument26 pagesBls - Acls Update American Heart Association 2020: Ns. Anastasia Hardyati., Mkep., Sp. KMBcelvin sohilait100% (1)

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) : Treatment & Medication MultimediaDocument2 pagesCardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) : Treatment & Medication Multimediapreet kaurNo ratings yet

- Ghiduriresuscitare2010V2 UnlockedDocument938 pagesGhiduriresuscitare2010V2 UnlockedMadalina Blaga100% (1)

- Referensi 7Document8 pagesReferensi 7Nophy NapitupuluNo ratings yet

- From MedscapeCME Clinical BriefsDocument4 pagesFrom MedscapeCME Clinical Briefssraji64No ratings yet

- 2009 UCSD Medical Center Advanced Resuscitation Training ManualDocument19 pages2009 UCSD Medical Center Advanced Resuscitation Training Manualernest_lohNo ratings yet

- CPR: Essentials of Cardiopulmonary ResuscitationDocument7 pagesCPR: Essentials of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitationdaniphilip777No ratings yet

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Update: Continuing Education ColumnDocument9 pagesCardiopulmonary Resuscitation Update: Continuing Education Columnkang soon cheolNo ratings yet

- Cardiac Arrest: Signs and SymptomsDocument7 pagesCardiac Arrest: Signs and SymptomsWebster The-TechGuy LunguNo ratings yet

- Adult Basic Life Support (BLS) ENGLISHDocument35 pagesAdult Basic Life Support (BLS) ENGLISHNicoleNo ratings yet

- Peri-Arrest Arrhythmias: AuthorsDocument11 pagesPeri-Arrest Arrhythmias: AuthorsMohammadAbdurRahmanNo ratings yet

- Manipal Manual of Resuscitation - 4th EditionDocument73 pagesManipal Manual of Resuscitation - 4th EditionAshlita Mendonca100% (2)

- Unit 5 Cardiac Emergencies: StructureDocument27 pagesUnit 5 Cardiac Emergencies: StructurebtaleraNo ratings yet

- CPR PDFDocument37 pagesCPR PDFArdhi AgustjikNo ratings yet

- Anzcor Guideline 11 10 1 Als Traumatic Arrest 27apr16Document11 pagesAnzcor Guideline 11 10 1 Als Traumatic Arrest 27apr16Mario Colville SolarNo ratings yet

- Comparison Sheet Based On 2010 AHA Guidelines For CPR and ECC BLS ChangesDocument5 pagesComparison Sheet Based On 2010 AHA Guidelines For CPR and ECC BLS ChangesCupit NubillisNo ratings yet

- Emergency Guidelines for Medical EmergenciesDocument72 pagesEmergency Guidelines for Medical EmergenciesRumana Ali100% (2)

- Advanced Cardiac Life Support: Valentina, MD, FIHADocument34 pagesAdvanced Cardiac Life Support: Valentina, MD, FIHAfaradibaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines - In-Hospital ResuscitationDocument18 pagesGuidelines - In-Hospital ResuscitationparuNo ratings yet

- 2015 CPR and ECC Guidelines UpdateDocument50 pages2015 CPR and ECC Guidelines UpdateAmy KochNo ratings yet

- Of The Main Changes in The Resuscitation GuidelinesDocument24 pagesOf The Main Changes in The Resuscitation GuidelinesYapa YapaNo ratings yet

- Special Circumstances Guidelines ALSDocument19 pagesSpecial Circumstances Guidelines ALSHamzaMasoodNo ratings yet

- Guidelines Postresuscitation CareDocument39 pagesGuidelines Postresuscitation CareParvathy R NairNo ratings yet

- Cardiopulmonary CardiopulmonaryDocument6 pagesCardiopulmonary CardiopulmonaryChris ChungNo ratings yet

- Special Circumstances GuidelinesDocument19 pagesSpecial Circumstances GuidelinesRayNo ratings yet

- Cardiac ArrestDocument30 pagesCardiac ArrestagnescheruseryNo ratings yet

- Core ACLS ConceptsDocument60 pagesCore ACLS ConceptsLex CatNo ratings yet

- DEFIBrilatorDocument43 pagesDEFIBrilatoranon_632568468No ratings yet

- Adult Advanced Life Support GuidelinesDocument11 pagesAdult Advanced Life Support GuidelinesDellaneira SetjiadiNo ratings yet

- Adult Advanced Life Support GuidelinesDocument11 pagesAdult Advanced Life Support GuidelinesRuvan AmarasingheNo ratings yet

- How to Perform CPR in 30 Seconds or LessDocument11 pagesHow to Perform CPR in 30 Seconds or LessAnkita BramheNo ratings yet

- Adult Advanced Life Support GuidelinesDocument11 pagesAdult Advanced Life Support Guidelinesrutba.ahmkhanNo ratings yet

- 6 CPRDocument27 pages6 CPRSuvini GunasekaraNo ratings yet

- Arc Guideline 11 1 Introduction To and Principles of in Hospital Resuscitation Feb 2019Document22 pagesArc Guideline 11 1 Introduction To and Principles of in Hospital Resuscitation Feb 2019hernandez2812No ratings yet

- 2010 AHA Guidelines For CPR and ECC Summary TableDocument0 pages2010 AHA Guidelines For CPR and ECC Summary TableUtami HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Practice: Adult and Paediatric Basic Life Support: An Update For The Dental TeamDocument4 pagesPractice: Adult and Paediatric Basic Life Support: An Update For The Dental TeamsmilekkmNo ratings yet

- Ischemic Stroke ManagementDocument8 pagesIschemic Stroke ManagementBa LitNo ratings yet

- 2020 AHA Guidelines For CPR & ECCDocument42 pages2020 AHA Guidelines For CPR & ECCArun100% (1)

- Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) Provider HandbookFrom EverandAdvanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) Provider HandbookRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Complications of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The Survival HandbookFrom EverandComplications of Percutaneous Coronary Intervention: The Survival HandbookAlistair LindsayNo ratings yet

- Essentials in Lung TransplantationFrom EverandEssentials in Lung TransplantationAllan R. GlanvilleNo ratings yet

- Oke BismillahDocument1 pageOke BismillahfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Yes We CanDocument1 pageYes We CanfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Jadwal Jaga Stase Bangsal 21 Maret - 31 Maret 2017Document4 pagesJadwal Jaga Stase Bangsal 21 Maret - 31 Maret 2017frakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Anestesi JurnalDocument10 pagesAnestesi JurnalfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Mah Sakirt RSIDocument1 pageMah Sakirt RSIfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Out 551Document10 pagesOut 551frakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Present As IDocument1 pagePresent As IfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- We GotDocument1 pageWe GotfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- G6PD Deficiency Prevalence and Estimates of Affected Populations in Malaria Endemic Countries: A Geostatistical Model-Based MapDocument101 pagesG6PD Deficiency Prevalence and Estimates of Affected Populations in Malaria Endemic Countries: A Geostatistical Model-Based MapfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Albumin Versus Other Fluids For Fluid Resuscitation in Patients With Sepsis: A Meta-AnalysisDocument22 pagesAlbumin Versus Other Fluids For Fluid Resuscitation in Patients With Sepsis: A Meta-AnalysisfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- TugasDocument4 pagesTugasfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Guidance For Intravenous Fluid and Electrolyte Prescription in AdultsDocument8 pagesGuidance For Intravenous Fluid and Electrolyte Prescription in AdultsfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Chronic and Recurrent Otitis Media-A Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesRisk Factors For Chronic and Recurrent Otitis Media-A Meta-AnalysisNadhira Puspita AyuningtyasNo ratings yet

- Fluid Resuscitation in Acute Illness - Time To Reappraise The BasicsDocument2 pagesFluid Resuscitation in Acute Illness - Time To Reappraise The BasicsAlina AndreiNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Rehabilitation FiDocument61 pagesPediatric Rehabilitation FifrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Paracetamol Distribution and Stability in Case of Acute Intoxication in Rats - ProQuest - 2Document9 pagesEvaluation of Paracetamol Distribution and Stability in Case of Acute Intoxication in Rats - ProQuest - 2frakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- S0733863514X00021 S0733863513001241 MainDocument17 pagesS0733863514X00021 S0733863513001241 MainfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- S0149291812X00031 S0149291812001695 MainDocument1 pageS0149291812X00031 S0149291812001695 MainfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Sri MurtiniDocument15 pagesSri MurtiniRatno AriyansahNo ratings yet

- Aku BisaDocument13 pagesAku BisafrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- ObatDocument3 pagesObatfrakturhepatikaNo ratings yet

- Types of ArrhythmiaDocument10 pagesTypes of ArrhythmiaRonilyn Mae AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Antagonis Reseptor Angiotensin 2, AIIRADocument31 pagesAntagonis Reseptor Angiotensin 2, AIIRAsuho exoNo ratings yet

- Simulink Heart Model For Simulation of The Effect of External SignalsDocument5 pagesSimulink Heart Model For Simulation of The Effect of External SignalsJhon Bairon Velásquez MiraNo ratings yet

- Presentation 1 - DR Martin RoyleDocument66 pagesPresentation 1 - DR Martin Royleশরীফ উল কবীরNo ratings yet

- Drug Study - NitroglycerinDocument2 pagesDrug Study - NitroglycerinKian Herrera100% (1)

- ACLS Study GuideDocument305 pagesACLS Study GuideRahma Rafina100% (2)

- BP 2017Document6 pagesBP 2017Rafael MeloNo ratings yet

- ECG Normal and AbnormalDocument74 pagesECG Normal and Abnormalawaniedream8391100% (1)

- Heart Failure Nursing Care Plans - 15 Nursing Diagnosis - NurseslabsDocument13 pagesHeart Failure Nursing Care Plans - 15 Nursing Diagnosis - NurseslabsJOSHUA DICHOSONo ratings yet

- Cardiovascular SystemDocument30 pagesCardiovascular SystemMale, Jezreel FayeNo ratings yet

- CM3 - Cu12 Assessment of Heart & Neck VesselsDocument15 pagesCM3 - Cu12 Assessment of Heart & Neck Vesselseli pascualNo ratings yet

- 3 PBDocument8 pages3 PBOtaku RPGNo ratings yet

- ECG Changes in myocardial infarctionDocument25 pagesECG Changes in myocardial infarctionginaulNo ratings yet

- اسئلة علم الدواءDocument2 pagesاسئلة علم الدواءMohamedErrmaliNo ratings yet

- Cardiology MCQ QuestionsDocument29 pagesCardiology MCQ QuestionsVimal NishadNo ratings yet

- Cardiac ICU admission criteriaDocument19 pagesCardiac ICU admission criteriaVina Tri AdityaNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Heart FailureDocument38 pagesPathophysiology of Heart FailureRizqy JoeandriNo ratings yet

- Acs - Case StudyDocument2 pagesAcs - Case StudyAubrie StellarNo ratings yet

- Anaesthesia Management of Patient of PacemakerDocument92 pagesAnaesthesia Management of Patient of PacemakerSiva KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 26 Management of Patients With Dysrhythmias and Conduction ProblemsDocument22 pagesChapter 26 Management of Patients With Dysrhythmias and Conduction ProblemsAbel C. Idusma Jr.No ratings yet

- hf305 00 Dfu DeuDocument54 pageshf305 00 Dfu DeuMauro EzechieleNo ratings yet

- ECG NotesDocument85 pagesECG NotesMalcum TurnbullNo ratings yet

- Kehamilan & Penyakit JantungDocument23 pagesKehamilan & Penyakit JantungSyifa NurainiNo ratings yet

- Quiz Cardiovascular Part 2 of 3Document47 pagesQuiz Cardiovascular Part 2 of 3MedShare100% (8)

- Cardiovascular SystemDocument34 pagesCardiovascular SystemArtika MayandaNo ratings yet

- Pre - and Post Test Cardiac ArrhythmiasDocument6 pagesPre - and Post Test Cardiac ArrhythmiasEköw Santiago JavierNo ratings yet

- Exercise Lab ResultsDocument7 pagesExercise Lab ResultsBarbora Hodasova0% (2)

- Apical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (AHC) : Robert Buttner Mike CadoganDocument36 pagesApical Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (AHC) : Robert Buttner Mike CadoganDeliberate self harmNo ratings yet

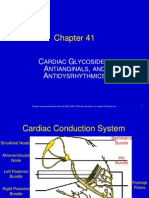

- C G, A, A: Ardiac Lycosides Ntianginals AND NtidysrhythmicsDocument21 pagesC G, A, A: Ardiac Lycosides Ntianginals AND NtidysrhythmicsPam LalaNo ratings yet

- Cardiology Summary PDFDocument62 pagesCardiology Summary PDFSyamsuriWahyuNo ratings yet