Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Greece Macro Focus March 12 2015

Uploaded by

orestiw1Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Greece Macro Focus March 12 2015

Uploaded by

orestiw1Copyright:

Available Formats

March 12, 2015

Greece needs neither wage deflation nor more fiscal

austerity; what is needed is an emphasis on

structural reforms to boost (non-price)

competitiveness

Dr. Platon Monokroussos

Group Chief Economist

Deputy General Manager

pmonokrousos@eurobank.gr

Introduction

DISCLAIMER

This report has been issued by

Eurobank Ergasias S.A. (Eurobank)

and may not be reproduced in any

manner or provided to any other

person. Each person that receives a

copy by acceptance thereof represents

and agrees that it will not distribute or

provide it to any other person. This

report is not an offer to buy or sell or a

solicitation of an offer to buy or sell the

securities mentioned herein. Eurobank

and others associated with it may have

positions in,

and may effect

transactions in securities of companies

mentioned herein and may also perform

or seek to perform investment banking

services for those companies. The

investments discussed in this report

may be unsuitable for investors,

depending on the specific investment

objectives and financial position. The

information contained herein is for

informative purposes only and has been

obtained from sources believed to be

reliable but it has not been verified by

Eurobank. The opinions expressed

herein may not necessarily coincide

with those of any member of Eurobank.

No representation or warranty (express

or implied) is made as to the accuracy,

completeness, correctness, timeliness or

fairness of the information or opinions

herein, all of which are subject to

change

without

notice.

No

responsibility or liability whatsoever or

howsoever arising is accepted in

relation to the contents hereof by

Eurobank or any of its directors,

officers or employees.

Any articles, studies, comments etc.

reflect solely the views of their author.

Any unsigned notes are deemed to have

been produced by the editorial team.

Any articles, studies, comments etc.

that are signed by members of the

editorial team express the personal

views of their author.

This note looks beyond the present state of negotiations with official creditors in the context of

the four month extension of Greeces Master Financial Assistance Facility Agreement (MFFA) that

th

was decided at February 20 Eurogroup.. It even looks beyond the pending completion of the

program review to argue that the emphasis of any succeeding arrangement between the

Eurogroup, the institutions and Greece should aim to boost the medium-term growth prospects of

the domestic economy. This would in turn require a strong emphasis on structural reforms to

boost the non-price competitiveness of the Greek economy so as to facilitate the needed

transition to a new development model emphasizing increased investment and extroversion. On

the other hand, the absence of structural reforms along with a renewed focus on draconian fiscal

austerity and wage deflation would increase the chances of a self-defeating fiscal adjustment with

severe consequences for fiscal sustainability, social cohesion and the long term growth prospects

of the Greek economy. The rest of this document is structured as follows: Part 1 provides as brief

assessment of the socioeconomic costs and benefits of the huge fiscal consolidation and wage

adjustment implemented in Greece in the context of the two consecutive bailout programs; Part 2

explains why a strong emphasis on structural reforms is need to boost Greeces non-price

competitiveness; and Part 3 concludes.

Part 1 - Greeces fiscal consolidation and wage adjustment: a brief cost-benefit analysis

1.1 The risk of self-defeating fiscal consolidation

The specter of self-defeating fiscal consolidations was initially raised in Gros (2011), where a simple

framework was utilized to show that fiscal austerity could increase the public debt ratio in the

short-run. Separately, Delong and Summers (2012) argue that in a depressed economy even a

1

small amount of hysteresis implies, by simple arithmetic, that expansionary (contractionary) fiscal

policy is likely to be self-financing (self-defeating). The authors clarify that their argument does

not justify unsustainable fiscal policies, nor does it justify delaying the passage of legislation to

make unsustainable fiscal policies sustainable. Yet, it is clear that the notion of hysteresis is of

particular relevance for fiscal consolidations undertaken during deep economic downturns, where

multipliers are likely to be both high and persistent i.e., their recessionary effects stretch well

beyond the year that the fiscal adjustment is implemented.

1.2 Cost and benefits of fiscal adjustment

Since 2010, Greece has implemented a massive fiscal adjustment that has been unprecedented by

recent historical standards (IMF, 2013). As per the estimates presented in Greeces 2015 Budget,

the ESA2010 General Government fiscal deficit has been reduced by more than 14ppts-of-GDP in

the past 5 years to c. -1.3%-of-GDP in 2014. Over the same period, the General Government

primary balance improved by around 11.5ppts-of-GDP, generating small surpluses in both 2013

Here, hysteresis is defined as the impact of the economic downturn on potential output.

March 12, 2015

and 2014, after recording a deficit of c. 10.5%-of-GDP in 2009. In cyclically-adjusted terms, the improvement in the primary

structural balance over the last five years has been even greater, amounting to more than 19ppts-of-GDP. Around two-thirds of this

adjustment has come from cuts in both discretionary and non-discretionary expenditure on e.g. social transfers, public wages and

government intermediate consumption. The remaining one-third has come from the revenue side, mainly as a result of higher

income and wealth taxes (Figure I.1 Appendix I). In what follows, we present a brief analysis on the potential costs and benefits

resulting from the aggressive fiscal consolidation and the significant wage adjustment implemented in recent years.

1.2.1 Costs of fiscal consolidation: exacerbation of domestic recession and rise in the debt ratio

It can be argued that the most severe costs of the aggressive, front-loaded fiscal consolidation implemented in the last 5 years relate

to: i) the exacerbation of the domestic recession; and ii) the large increase in the public debt ratio since 2009, despite the

restructuring of the privately-held Greek debt (PSI), the debt buyback (DBB) operation implemented in 2012 and the debt relief

package agreed at the November 2012 Eurogroup (i.e., further maturity extensions and lower interest rates on EU loans provided

under the two consecutive bailout programs).

Fiscal consolidation impact on domestic GDP

This section examines the macroeconomic effects of the fiscal consolidation program implemented in the last 5 years. To do so, we

first assume three alternative values for the impact multiplier: -1.5 high multiplier; -1 intermediate multiplier; and -0.5 low

multiplier. The interpretation of these values is as follows: for the high multiplier value, we assume that a fiscal contraction (i.e.,

decrease in government expenditure or rise in tax revenue) of 1 euro that is implemented in a given year leads to a decrease in

nominal GDP by 1.5 euro in that year. A similar interpretation applies to the other two impact multiplier values. Furthermore, in

order to incorporate multiplier persistence and hysteresis effects, we follow Boussard et al. (2012) and European Commission (2012,

2013) and assume that fiscal multipliers follow the convex, autoregressive decaying path analyzed in Appendix II. As a next step, we

utilize available fiscal data to get an appropriate metric for the thrust of fiscal austerity policies implemented in Greece over the

period 2010-2014. In the study presented herein, this metric represents the annual change in the structural primary fiscal balance

2

based on the relevant data presented in the IMF Fiscal Monitor (October 2014). Table I.1 of Appendix I portrays the macroeconomic

effects of the fiscal austerity policies implemented in Greece over the period 2010-2014. In more detail, it shows the estimated GDP

impact under different scenarios regarding the value of the impact multiplier, the degree of multiplier persistence and the existence

or not of hysteresis effects. In Table I.1 we actually present the results for two such scenarios, which incorporate the intermediate

3

and low impact multiplier values assumed in this study. As it is implied by the results presented in the said table, the aggressive

fiscal consolidation program implemented in Greece over the period 2010-2014 has indeed taken a heavy toll on domestic economic

activity.

Fiscal consolidation impact on the debt ratio

In what follows, we examine the paradox of the sharp increase in the debt ratio since 2009, despite the aggressive fiscal

consolidation and the debt relief operations implemented over the last several years. Greeces gross public debt ratio has increased

by c. 48ppts-of-GDP between end-2009 and end-2014 to stand to an estimated 177%-of-GDP at the end of that period. As per the

4

most recent European Commission estimates (AMECO), the cumulative snow ball effect on Greek public debt over the

aforementioned period was c. 70ppts-of-GDP, which implies that the large increase in the debt ratio since 2009 was exclusively due

to the domestic economic recession. This development comes as no major surprise, especially taking into account the steep GDP

5

contraction over that period (denominator effect) and its impact on key fiscal metrics (numerator effect) . The possibility of an initial

rise in the debt ratio following an aggressive fiscal adjustment constitutes a topic that has been analyzed, to some extent, in the

6

recent empirical literature . In fact, in a recent study we demonstrated that, taking into account Greeces present debt-to-GDP ratio,

the critical value of the fiscal multiplier that prevents a (contemporaneous) rise in the debt ratio following a fiscal adjustment

A well-known methodological issue in the empirical estimation of fiscal multipliers relates to the identification of purely exogenous fiscal shocks.

For the purpose of our analysis, we assume that fiscal shock in year t is represented by the annual change in the structural general government

primary balance (from year t-1 to year t).

3

Multipliers tend to be higher in deep economic downturns. However, some recent empirical studies have demonstrated that heightened fiscal

sustainability concerns tend to, ceteris paribus, reduce the value of the fiscal multiplier.

4

The snowball effect denotes the automatic decrease (increase) in the debt ratio when nominal GDP growth in year t rises above (falls below) the

average effective interest rate in that year. In mathematical terms, the snowball effect is defined as the difference between the average effective

interest rate and nominal growth.

5

For instance, in a deep recessionary period, the government may face higher costs for unemployment benefits. Furthermore, a sharp decline in

economic activity may see the incomes of a higher number of tax payers falling below the tax-exempt threshold than in normal economic times.

6

See e.g. European Commission (2012).

March 12, 2015

7,8

implemented in a given year is around 0.5. In other words, a fiscal adjustment undertaken in year t would lead to an initial rise in

the debt ratio if the size of the fiscal multiplier in that year is equal or greater than 0.5. For Greece, the existing literature and our

earlier empirical findings suggest that, in deep economic contractions, the size of the fiscal multiplier may well exceed the

9

aforementioned threshold and, in certain instances, be even higher than 1.

1.2.2 Benefits of the fiscal consolidation program: elimination of unsustainable fiscal deficits, provision of unprecedented

amounts of official-sector financing and decline in debt rollover risks

Since its euro area entry, Greece accumulated huge macroeconomic imbalances which could not be sustained in the new period

following the outbreak of the global financial crisis. Against this backdrop, the two consecutive adjustment programs agreed with

official creditors (in May 201o and in March 2012, respectively) have been instrumental in correcting huge deficits accumulated in

the countrys fiscal and external accounts. Moreover, the provision of an unprecedented amount of official sector financing to

replenish collapsing State cash reserves and to inject much-needed liquidity (and fresh capital) in the domestic banking system has

prevented a much more dramatic deleveraging of the domestic economy, which could instigate even more severe economic and

social costs. In addition to all these, the debt relief operations implemented in the context of the two adjustment programs (PSI,

DBB, maturing extensions and reductions in interest rates on EU loans) have greatly improved the serviceability of Greek public

debt. Indeed, over the coming 5-year period, the average effective interest rate on Greek debt is expected to be not much higher

than 3% (i.e., remaining amongst the lowest in the euro area), while the overall annual interest expense is expected to average

between 4% and 4.5% of GDP compared to levels around 9% or 10% of GDP that would prevail in the absence of the

aforementioned operations.

1.3 Wage adjustment

The implementation of the two consecutive adjustment programs has restored wage competitiveness, with Greeces ULCs-based

REER having already declined to levels prevailing in mid-90s. This has already benefited Greeces export performance as confirmed

by the results of a special econometric study summarized later in this document (see section 2.2), which documents a -0.26 longterm elasticity of real Greek goods exports with respect to the real effective exchange rate. Yet, Greeces wage adjustment over the

last few years has probably been too aggressive and, in any case, was not accompanied by a similarly aggressive decline in domestic

consumer prices. The latter is true despite the huge output gap and primarily reflects lingering rigidities/existence of oligopolistic

structures in domestic product and services markets. Undoubtedly, these developments have put additional pressure on disposable

incomes, further exacerbating the domestic recession (Figures 1 & 2).

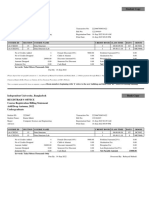

Figure 1- Nominal compensation in manufacturing (EUR thousand)

60

50

40

Eurozone

30

Germany

20

Greece

10

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

The fiscal multiplier is defined as the ratio of a change in output to an exogenous change in the fiscal deficit with respect to their baselines.

The Challenge of Restoring Debt Sustainability in a Deep Economic Recession: The case of Greece, Platon Monokroussos, GreeSE Paper No.87,

Hellenic Observatory Papers on Greece and Southeast Europe, October 2014

8

http://www.lse.ac.uk/europeanInstitute/research/hellenicObservatory/CMS%20pdf/Publications/GreeSE/GreeSE-No87.pdf

9

Monokroussos, Platon and Thomakos, Dimitris, 2012, Fiscal Multipliers in deep economic recessions and the case for a 2-year extension in Greeces

austerity programme, Economy & Markets, Global Markets Research, Eurobank Ergasias S.A.

Monokroussos, Platon and Thomakos, Dimitris, 2013, Greek fiscal multipliers revisited Government spending cuts vs. tax hikes and the role of public

investment expenditure, Economy & Markets, Global Markets Research, Eurobank Ergasias S.A.

March 12, 2015

Figure 2- Nominal compensation in services (EUR thousand)

50

40

30

Eurozone

20

Germany

Greece

10

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

Source: AMECO

Part 2 Why a strong emphasis on structural reforms is needed to boost competitiveness

The material included in this section is based on the key findings of a special study we presented at a major Eurobank event that was

organized in Athens in November 2014. The study consisted of three main sections. The first one analyzed the intertemporal

evolution of Greek exports of goods and services and examined Greeces export performance vis--vis its main trade partners. The

second presented the results of an empirical study on the main drivers of Greek manufacturing and non-manufacturing goods

exports, based on monthly data spanning the period Jan. 1998 Dec. 2013. Finally, the third section presented the main findings of a

poll we conducted among 222 (large and medium-sided) domestic exporters with the purpose of getting a better understanding of

the industrys view as regards the main factors hindering export performance as well as current trends and prospects. In what

follows, we summarize some of the main results of the aforementioned study, which highlight the need for a strong emphasis of

structural reforms in the domestic product and services markets with a view to further boost Greeces non-exports competitiveness.

Additional analysis on the said results is provided in Appendix III at the end of this document.

2.1 A brief overview of the progress made in recent years to improve Greeces competitiveness

Dynamic bounce in investment and improved export performance are needed to boost medium-term growth

Final consumption expenditure (private and public) continues to account for a disproportionately high share of Greek GDP (c

90% vs. 75% in the euro area). This implies that a key prerequisite for a return to positive and sustainable growth rates going

forward is a stronger exports performance coupled with a notable recovery in domestic investment activity.

The latter is especially relevant taking into account the still negative saving rate of households (-6% of average nominal

disposable income) and the need to maintain significant primary fiscal surpluses in the following years.

The performance of Greek goods and services exports has improved in the last couple of years, but continues to lag behind that

of other EU countries in the period following the outbreak of the global financial crisis. As a percent of GDP, Greek exports

remain significantly lower than the euro area average (c. 33% vs. 47%).

Lingering structural problems hindering Greeces competiveness and export performance

Greece remains a small and closed economy with limited gains in world market shares, even following the huge wage

adjustment in the past several years that has reduced Greeces ULCs-based Real Effective Interest Rate (REER) to levels

prevailing before the EUR adoption.

With the exception of maritime shipping and mineral fuels, lubricants & related material all other main categories of goods and

services exports have seen their share (as % of total Greek exports) shrinking over the last two decades.

The technological content of Greek manufacturing exports remains low relative to that of the main EU trading partners.

March 12, 2015

Greece features a competitive advantage in more traditional manufacturing sectors which, to a large extent, are of low

technological content and low added value.

Greece lags behind its main EU trading partners in merchandise trade specialization

Greece continues to lag behind its main trading partners in business R&D expenditure and foreign direct investment.

The average size of Greek manufacturing companies remains significantly lower relative to EU trading partners. This hinders

the generation of economies of scale and prevents a better integration into global supply chains.

thought significant progress in several important areas has been attained in recent years

Significant progress has been made in recent years as regards the diversification of Greek exports in terms of structure and

geographical destination.

The technological content of Greek exports has increased significantly over the past decade and a higher share of domesticallyproduced manufacturing goods is now exported to high growth foreign economies.

Greeces manufacturing exports have rebounded in the last couple of years.

Significant progress has been attained in recent years in a number of international indicators for Greeces competitiveness,

governance as well as the functioning of the domestic business and regulatory environment. However, additional

improvements are needed to bridge the gap with the rest of the Eurozone

2.2 Summary of results of empirical study on the main drivers of Greek exports

Data and methodology

The study utilizes monthly-frequency, time-series data for the value of Greek goods exports (SITC classification). The source of the

data is EL.STAT and the period under examination is January 1998-December 2013. The data have been seasonally adjusted and

deflated by the producer price index for exports. Initially, the series were examined for their statistical properties, so as to determine

the appropriate modeling strategy. Then, a number of model specifications were created to explain the volatility of the real value of

exports based on a number of explanatory variables.

The explanatory variables include, among others:

alternative proxies of foreign demand e.g. weighted GDP volume index of 37 trading partners; EU-28 merchandise import

demand index; OECD merchandise import demand index; OECD-Europe industrial production index; 37 trading partner

merchandise import demand index (EU28, Australia, Canada, Japan, Mexico, N. Zealand, Norway, Switzerland, Turkey, US)

alternative proxies for price competitiveness e.g. real effective exchange rate (REER) indices for Greece based on relative

ULCs and consumer price inflation rates against different trade partner groups.

more than 20 non-price competiveness indicators measuring various important aspects of the domestic business, institutional

and regulatory environment, such as: technological content of Greek exports; degree of market size, concentration and average

exporting firm size in the Greek manufacturing sector; degree of Greek exports concentration (Herfindahl Hirschman

concentration index); relative performance (vs. main trade partners) as regards Business R&D and FDI; ease in starting a

business, ease in getting credit, corporate tax burden and ease of paying taxes; enforcement of contracts; quality of regulatory

environment etc.

Empirical results

Figure 1 below provides a graphical depiction of the estimated long-term elasticities of Greek goods exports with respect to external

demand and price competitiveness indicators. Another important result of our study is the statistical significance of some of the

non-price competitiveness indicators under examination, when they enter (either individually or jointly) as explanatory variables

March 12, 2015

along with foreign demand and the real effective exchange rate in a number of model specifications. (Full set of empirical results is

available upon request).

Figure 1 - Long-term effect of external demand and REER on Greeces real goods exports

Estimated long-term elasticities (% Increase/decrease of exports for every 1% increase/decrease of explanatory variables

Long-term impact of external demand

Long-term impact of the real effective exchange rate

-8.0 -6.0 -4.0 -2.0

0.0

2.0

4.0

6.0

8.0

10.0 12.0

FOOD & LIVE ANIMALS (SITC 0)

BEVERAGES & TOBACCO (SITC 1)

CRUDE MATERIALS, INEDIBLE EXCEPT FUEL (SITC 2)

MINERAL FUELS, LUBRICANTS & RELATED MATERIALS

(SITC 3)

ANIMAL & VEGETABLE OILS, FATS & WAXES (SITC 4)

CHEMICALS & RELATED PRODUCTS N.E.S. (SITC 5)

MANUFACTURED GOODS CLASSIFIED CHIEFLY BY

MATERIAL (SITC 6)

MACHINERY & TRANSPORT EQUIPMENT (SITC 7)

MISCELLANEOUS MANUFACTURED ARTICLES (SITC 8)

COMMODITIES AND TRANSACTIONS NOT CLASSIFIED

ELSEWHERE (SITC 9)

ALL MANUFACTURING SECTORS (SITC 5-8)

ALL SECTORS EXCLUDING MANUFACTURING (SITC 0-4 &9)

ALL SECTORS EXCLUDING MINERAL, FUELS (SITC 0-9

EXCL. 3)

-0.26

0.95

2.88

-1.88

-0.28

0.88

Source: EL.STAT, Eurobank Economic Research

Explanatory note

The estimated long-term elasticities presented in Figure 1 are based on the following proxies

External demand: weighted GDP volume index of 37 trading partners on the basis of share of exports of Greece towards respective

markets;

Real effective exchange rate of Greece against 138 trading partners based on the relevant CPI (total economy);

Real effective exchange rate of Greece against 30 trading partners on the basis of relative cost per unit of output (business sector)

Part 3 - Concluding remarks

The two consecutive adjustment programs implemented in Greece over the last 5 years have been instrumental in correcting huge

fiscal imbalances accumulated in the period leading to the global financial crisis and in improving the serviceability of Greek public

debt. The concomitant provision of an unprecedented amount of official-sector financing has also prevented a more aggressive

deleveraging in the domestic economy that could further exacerbate the domestic recession. However, the horizontal and frontloaded nature of the applied fiscal adjustment conspired with an inadequate degree of focus on structural reforms to instigate

sizeable macroeconomic and social costs. With domestic authorities having already managed to stabilized the fiscal balance (and to

even generate small primary surpluses in 2013 and 2014), any succeeding arrangement agreed with official lenders should aim to

maintain the sizeable improvement attained in Greeces fiscal account in recent years. Yet, as we have argued in a in one of our

10

recent research notes , the provision of additional debt relief (OSI) coupled with a certain relaxation of the primary fiscal target and

an increased emphasis on structural reforms could go a long way towards facilitating a return to positive and sustained economic

growth rates.

10

Why a relaxation of the primary fiscal target may prove to be a self-financing policy shift, Greece Macro Monitor, Eurobank Economic Research,

February 26, 2015, http://www.eurobank.gr/Uploads/Reports/GREECEMACROFOCUSFebruary262015.pdf.

March 12, 2015

Appendix I

Figure and Table for Part I

Figure I. 1 - Structure of Greeces fiscal adjustment in 2008-2013

4

Fiscal Adjustment in Expenditures, 2008-13

(percent of potential GDP)

-1

Gross capital

formation

Social benefits

-1

Intermediate

consumption

Compensation of

employees

Interest

Capital transfers

Other current

transfers

Subsidies

4

Fiscal Adjustment in Revenues, 2008-13

(percent of potential GDP)

-1

-1

Income& wealth

taxes

Sales

Production&

import taxes

Capital transfers

Social

contributions

Other current

transfers

Property income

Source: EC, IMF, Eurobank Research

Table I.1 - Estimated impact of fiscal austerity on nominal GDP, ceteris paribus basis (in EURbn)

Low multiplier/low persistence/"no hysteresis"

Intermediate multiplier/low persistence/"no

hysteresis"

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

-8.4

-9.3

-8.1

-6.6

-3.6

-16.8

-18.6

-16.3

-13.2

-7.2

-10.7

-18.8

-13.7

-12.0

-3.5

7.4

4.9

3.6

2.8

0.3

16.8

10.2

7.0

5.1

0.5

Memorandum items

Annual change in nominal GDP (EURbn)

Annual change in structural primary balance in pptsof-GDP / + sign for improvement

Annual change in structural primary balance in

EURbn / + sign for improvement

Source: IMF (Oct 2014), EL.STAT. Eurobank Research

March 12, 2015

Appendix II

Impact multipliers, multiplier persistence & hysteresis assumptions (Part I)

In order to incorporate multiplier persistence in our simulation exercise we follow Boussard et al. (2012) and European Commission

11

(2012, 2013) and assume that fiscal multipliers follow the following convex, autoregressive decay path :

i-t

mt,i = (m1 ) +

where, m1 is the impact (i.e., first year) multiplier, mt,I is the fiscal multiplier applying in year i following a permanent fiscal shock in

year t, 0 < < 1; and is the long-run impulse response of GDP to fiscal consolidation. negative value of indicates that

hysteresis effects are present (see e.g. de Long and Summers, 2012). A positive one represents a situation in which a consolidation

today boosts long term growth by e.g. reducing the interest rate and by lessening the crowding out on private investment.

The figure below depicts the decaying path of the fiscal multiplier assumed in the simulation exercise presented in this study. Here,

the initial value of the (impact) multiplier is assumed to take one of the following three values: -1.5 high multiplier; -1.0

intermediate multiplier and -0.5 low multiplier. Moreover, high persistence corresponds to the following parameter value:

=.8 and low persistence corresponds to =.5. Finally, for the presence of hysteresis effects we assume =-0.2, while the case

of =0 corresponds to no hysteresis effects.

Figure: Response of GDP to one-off cyclical adjustment

0.0

1

11 13 15 17 19 21

-0.2

High multiplier /high

persistence/"hysteresis"

-0.4

High multiplier / high persistence / "no

hysteresis"

-0.6

High multiplier / low persistence /"no

hysteresis"

-0.8

Intermediate multiplier / high

persistence /"hysteresis"

-1.0

Intermediate multiplier / high

persistence /"no hysteresis"

-1.2

Intermediate multiplier / low

persistence /"no hysteresis"

-1.4

Low multiplier/low persistence /"no

hysteresis"

-1.6

Source: EC (September 2013); Eurobank Global Markets Research

Note: Response of GDP in years t=1,,21 per one unit cut in cyclically adjusted primary balance in year t=1. Assuming that the same

logic applies, then a unit increase in the cyclically adjusted primary balance in year t=1, would lead to a GDP response that could be

portrayed by inverting the above figure.

11

This decay function reproduces relatively well the shape of the impulse-response function by typical DSGE models for most of the permanents

fiscal shocks.

March 12, 2015

Appendix III - Why competitiveness and extroversion constitute the cornerstones of a new economic development model for

Greece

Continuing fiscal prudence and domestic household dissaving suggest long-term growth must necessarily come from higher exports

and investments (figures 1&2)

Figure 1 Final consumption expenditure continues to represent a disproportionally high share of Greek GDP; investment spending

(as % of GDP) has collapsed due to the domestic recession and currently stands well below the respective euro area average

120.0

Final consumption expenditure (% GDP)

Greece

100.0

90.0

80.0

60.0

Euro area (annual average = 76.6%)

40.0

Greece

Gross fixed capital formation (% GDP)

20.0

2014(f)

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

11.5

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

1999

1998

2000

Euro area (average annual average = 21.6%)

0.0

Figure 2 Greek exports of goods and services (as % of GDP) remain significantly lower than the respective euro area average

46.7

50

Exports of goods & services (% GDP)

40

32.5

30

20

10

Greece

Euro area

2016

2015

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

1994

1993

Source (Figures 1 & 2): EMECO, Eurobank Economic Research

Greeces exports performance has broadly lagged behind that of other euro area countries throughout the crisis period

Figure 3 Exports of goods & services in 2010 prices (2008=100)

150

140

130

Ireland

120

Greece

110

Spain

100

Latvia

90

Portugal

80

70

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Source (Figure 3): EMECO, Eurobank Economic Research

2015

2016

March 12, 2015

despite the huge adjustment in wages and, to a lesser extent, in relative inflation rates vis a vis main trading partners

Figure 4 Greeces REER relative to 37 trading partners (cumulative annual change)

25.0%

based on relative inflation rates

20.0%

based on relative ULCs

15.0%

10.0%

5.0%

0.0%

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2001

2002

-5.0%

Figure 5 Nominal wage expenditure per employee (annual change)

15.0%

Euro area

10.0%

Greece

5.0%

0.0%

-5.0%

2014

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

-10.0%

Source (Figures 4 & 5): EMECO, Eurobank Economic Research

Greece remains a small closed economy with limited gains in world market shares over the last two decades

Figure 6 Average ratio of Greek exports of goods & services to GDP (1995-2013)

(Bold columns indicate size of economy smaller than the median)

160

140

120

100

80

60

23.0%

40

L

IE

M

S

B

E

H

N

C

SI

L

B

A

L

D

C

C

S

M

K

N

IS

FI

H

M

D

P

C

R

P

R

N

M

G

E

IT

F

T

G

A

J

U

20

Figure 7 Greece: exports as % of world imports

1.6

1.4

% 1.2

Services

1.0

Goods

0.8

0.6

Goods &

Services

0.4

0.2

Source (Figures 6 & 7): OECD, UNCTAD, Eurobank Economic Research

10

2013

2012

2011

2010

2009

2008

2007

2006

2005

2004

2003

2002

2001

2000

1999

1998

1997

1996

1995

0.0

March 12, 2015

Declining share of manufacturing exports and increasing share of shipping services exports (as % of total respective Greek

exports)

Total value of exports in 2013 (USD billions)

Goods = 27.57bn /Services = 27.9bn

Figure 8 Goods exports - main categories as % of total

50.0

40.0

30.0

20.0

10.0

0.0

Manufacturing

2013

Other

Michellaneous

manufacturing

articles

Machinery and

transportation

equipment

Manufactured

goods classified

chiefly by material

Chemicals &

related products

(n.e.s.)

Animal &

vegetable oils,

fats and waxes

Mineral fuels,

lubricants &

related materials

Crude materials

except fuels

Beverages &

tobacco

Food & live

animals

1998

Figure 9 Services exports - main categories as % of total

60.0

50.0

40.0

30.0

20.0

10.0

0.0

1998

Other business

services

Royalties

IT services

Monetary

Insurance

Communications

Travel (mainly

tourism)

Transportation

(mainly shipping)

2013

Source (Figures 8 & 9): EL.STAT. BoG, Eurobank Economic Research

The technological content of Greek manufacturing exports remains low relative the main EU trading partners

Figure 10 Production of manufacturing goods of high & medium-high technological content

(% total manufacturing output)

70.0

60.0

50.0

40.0

U-27

30.0

Germany

Greece

20.0

10.0

0.0

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

Source (Figure 10): UNCTAD, Eurobank Economic Research

11

2011

2012

2013

March 12, 2015

Greece features a competitive advantage in more traditional manufacturing sectors which, to a large extent, are of low

technological content

12

Figure 11 Greece - Revealed Comparative Advantage (SITC, Rev.4)

(A comparative advantage is revealed if RCA>1)

10

2008

2013

8

6

4

2

62 - Rubber

manufactures

54 - Medicinal and

pharmaceutical

products

5 - Chemicals and

related products

33 - Petroleum,

petroleum products

and related materials

64 - Paper,

paperboard and

related products

63 - Cork and wood

manufactures

61 - Leather, leather

manufactures

85 - Footwear

84 - Articles of

apparel and clothing

accessories

65 - Textile yarn,

fabrics, and related

products

12 - Tobacco

11 - Beverages

0 - Food

6

5

2008

2013

4

3

2

1

82 - Furniture

8 - Miscellaneous

manufactured

articles

7 - Machinery and

transport equipment

6 - Manufactured

goods classified

chiefly by material

4 - Animal and

vegetable oils, fats

and waxes

3 - Mineral fuels,

lubricants and

related materials

2 - Crude materials,

inedible, except fuels

69 - Manufactures of

metals, n.e.s.

66 - Non-metallic

mineral

manufactures, n.e.s.

Source (Figure 11): UNCOMTRADE, Eurobank Economic Research

Greece lags its main EU trading partners in merchandise trade specialization

13

Figure 12 Merchandise trade specialization index (Greece vs. EU-27)

Greece

0.0

-0.2

-0.4

-0.6

1995

-0.8

2012

12

Other manufactured

goods (SITC 6 + 8

less 667 and 68)

Electronic excluding

parts and

components (SITC

751 + 752 + 761 +

762 + 763 + 775)

Machinery and

transport equipment

(SITC 7)

Chemical products

(SITC 5)

Manufactured goods

(SITC 5 to 8 less 667

and 68)

-1.0

The Revealed Comparative Advantage Index is contracted as the ratio of a products share of exports (or category of exports) as % of a countrys

total exports to the corresponding ratio of a trading partner or group of trading partners. A comparative advantage is revealed if RCA>1

13

The Merchandise Trade Specialization index compares the net flow of goods or groups of tradable goods (exports minus imports) to the total flow

of the respective product or tradable product group (exports plus imports) The range of values is between -1 and 1. A positive value indicates that an

economy has net exports (hence it specializes in the production of that specific product) and a negative value means that an economy imports more

than it exports (net consumption).

12

March 12, 2015

14

Figure 12 continued Merchandise trade specialization index (Greece vs. EU-27)

EU-27

0.2

0.1

0.1

0.0

-0.1

-0.1

-0.2

-0.2

2012

Other manufactured

goods (SITC 6 + 8

less 667 and 68)

Electronic excluding

parts and

components (SITC

751 + 752 + 761 +

762 + 763 + 775)

Machinery and

transport equipment

(SITC 7)

Chemical products

(SITC 5)

Manufactured goods

(SITC 5 to 8 less 667

and 68)

1995

Source (Figure 12): UNCTAD, Eurobank Economic Research

Greece: significant underperformance in R&D expenditure and foreign direct investment relative to main trading partners

Figure 13 Inward and outward foreign direct investment stock, annual (% GDP)

60

50

40

Greece

30

World

EU-28

20

10

0

1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Figure 14 Business R&D expenditure (% GDP)

25.0

20.0

Greek R&D as %

German R&D

15.0

10.0

Greek R&D as %

EU-27 R&D

5.0

0.0

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Source (Figures 13 & 14): UNCTAD, Eurostat, Eurobank Economic Research

14

The Merchandise Trade Specialization index compares the net flow of goods or group of tradable goods (exports minus imports) to the total flow

of the respective product or tradable product group (exports plus imports). The range of values is between -1 and 1. A positive value indicates that

the economy has net exports (hence it specializes in the production of that specific product) and a negative value indicates that the economy imports

more than it exports (net consumption).

13

March 12, 2015

However, not all trends are problematic. Significant progress has been made in recent years in relation to the diversification of

Greek exports in terms of structure and geographical destination

Figure 15 Greek exports of goods towards main geographical destinations (bn US dollars)

40

35

30

EU countries excl.

Euro Area

25

20

Non EU Countries

15

10

Euro Area

0

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

Figure 16 Share of exports of major branches of Greek manufacturing industry (% of total)

A food, beverage; and tobacco

B textiles and textile products

J basic metals and fabricated metal products

other and plastic mineral products

C leather and leather products

K machinery and equipment nor elsewhere classified

D wood and wood products

L electrical and optical equipment

E paper and paper products

M transport equipment

G chemicals and chemical products N not elesewhere classified

H rubber and plastic products

Source (Figures 15 & 16): OECD, IMF, Eurobank Economic Research

14

March 12, 2015

Increase in exports of the Greek manufacturing industry to rapidly developing economies in recent years, albeit at a slightly lesser

extent than the rest of the Eurozone

Figure 17 Greeces manufacturing industry exports to the 27 fastest growing economies as % of total exports of the Greek

15

manufacturing industry

20.0

18.0

16.0

14.0

12.0

10.0

8.0

6.0

4.0

2.0

0.0

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

To the extent that the recent increase in the concentration of Greek exports enhances the degree of market power in export

businesses, this process must be continued and intensified through eg. mergers & acquisitions in key manufacturing sectors

Figure 18 - Concentration index of Greek merchandise exports to EU27 and the euro area

16

(Herfindahl-Hirschmann bilateral concentration index)

0.15

0.14

0.13

0.12

0.11

0.10

Greece - Eurozone

0.09

Greece - U27

0.08

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

Source (Figures 17 & 18): UNCTAD, Eurobank Economic Research

Visible signs of recovery in domestic industrial and manufacturing activity

Figure 19 - Greeces Purchasing Managers Index

60

Expansion

55

50

Contraction

45

48.8 Oct.

40

15

Aug-14

Mar-14

Oct-13

May-13

Dec-12

Jul-12

Feb-12

Sep-11

Apr-11

Nov-10

Jun-10

Jan-10

Aug-09

Mar-09

Oct-08

May-08

Dec-07

Jul-07

Feb-07

Sep-06

Apr-06

Nov-05

Jun-05

Jan-05

35

Fastest growing economies are defined here as those that featured average annual GDP growth of more than 4% over the last 10 years and

nominal GDP higher than $100bn in 2013.

16

The Herfindahl-Hirschmann index measures market concentration. It indicates whether the exports of a country or group of countries are

concentrated on certain products or alternatively distributed more homogeneously among a range of products. It takes values from 0 (zero

concentration) to 1 (maximum concentration).

15

March 12, 2015

Figure 20 Business expectations in manufacturing

20

10

0

-10

-20

-30

Greece

Eurozone

-40

Aug-14

Dec-13

Apr-13

Aug-12

Dec-11

Apr-11

Dec-09

Aug-10

Apr-09

Dec-07

Aug-08

Apr-07

Aug-06

Apr-05

Dec-05

Aug-04

Apr-03

Dec-03

Aug-02

Apr-01

Dec-01

Aug-00

Dec-99

Apr-99

Aug-98

Dec-97

Apr-97

-50

Source (Figures 19 & 20): EC, Markit, Eurobank Economic Research

Greece - Significant progress in a number of international indicators for competitiveness, the domestic business environment and

governance, although further improvement is needed to bridge the gap with the rest of the Eurozone

Figure 21 Greece - World Bank Doing Business Report; Key indicators

95.0

85.0

EU-17 (mean)

75.0

65.0

Greece

55.0

min-all countries

45.0

35.0

max-all countries

25.0

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

Greece

Euro area

Executive

Accountability

Environmental

Sustainability

Social

Sustainability

Economic

policies

Rule of Law

Civil rights

Access to

Information

Electoral

Process

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Executive

Capacity

Figure 22 OECD Sustainable Governance indicators, 2014

Figure 23 Greece: World Bank Doing Business Report; Key Indicators

100

DB 2005

80

DB 2015

60

40

20

16

Resolving

Insolvency

Enforcing Contracts

Trading Across

Borders

Paying Taxes

Protecting

Investors*

Getting Credit*

Registering

Property

Dealing with

Construction

Permits

Starting a Business

17

Greece

Innovation

(smallest number denotes better position)

Business

sophistication

Market size

Technological

readiness

Financial market

development

Labor market

efficiency

Goods market

efficiency

Higher

education and

training

160

140

120

100

80

60

40

20

0

Health and

primary

education

Macroeconomic

environment

Infrastructure

Institutions

March 12, 2015

Figure 24 WEF: Global Competitiveness Indicator, 2014 Rankings

Euro area

March 12, 2015

Eurobank Global Markets Research

Global Markets Sales

Global Markets Research Team

Dr. Platon Monokroussos: Group Chief Economist

pmonokrousos@eurobank.gr, + 30 210 37 18 903

Paraskevi Petropoulou: G10 Markets Analyst

ppetropoulou@eurobank.gr, + 30 210 37 18 991

Galatia Phoka: Emerging Markets Analyst

gphoka@eurobank.gr, + 30 210 37 18 922

Anna Dimitriadou: Economist

andimitriadou@eurobank.gr, + 30 210 37 18 793

Nikos Laios: Head of Treasury Sales

nlaios@eurobank.gr, + 30 210 37 18 910

Alexandra Papathanasiou: Head of Institutional Sales

apapathanasiou@eurobank.gr, +30 210 37 18 996

John Seimenis: Head of Corporate Sales

yseimenis@eurobank.gr, +30 210 37 18 909

Achilleas Stogioglou: Head of Private Banking Sales

astogioglou@eurobank.gr, +30 210 37 18 904

George Petrogiannis: Head of Shipping Sales

gpetrogiannis@eurobank.gr, +30 210 37 18 915

Vassilis Gioulbaxiotis: Head International Sales

vgioulbaxiotis@eurobank.gr, +30 210 3718995

Eurobank Global Markets Research

More research editions available at htpp://www.eurobank.gr/research

Greece Macro Monitor: Periodic overview of key macro & market developments in Greece

Daily overview of global markets & the SEE region:

Daily overview of key developments in global markets & the SEE region

South East Europe Bi-Monthly:

Monthly overview of economic & market developments in the SEE region

Global Markets & SEE themes: Special focus reports on Global Markets & the SEE region

Eurobank Ergasias S.A, 8 Othonos Str, 105 57 Athens, tel: +30 210 33 37 000, fax: +30 210 33 37 190, email: EurobankGlobalMarketsResearch@eurobank.gr

Subscribe electronically at htpp://www.eurobank.gr/research

Follow us on twitter: https://twitter.com/Eurobank Group

18

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Lifespan Development Canadian 6th Edition Boyd Test BankDocument57 pagesLifespan Development Canadian 6th Edition Boyd Test Bankshamekascoles2528zNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Case StudyDocument2 pagesCase StudyBunga Larangan73% (11)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- 3ccc PDFDocument20 pages3ccc PDFKaka KunNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Controle de Abastecimento e ManutençãoDocument409 pagesControle de Abastecimento e ManutençãoHAROLDO LAGE VIEIRANo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Traffic LightDocument19 pagesTraffic LightDianne ParNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- تاااتتاااDocument14 pagesتاااتتاااMegdam Sameeh TarawnehNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Reflection Homophone 2Document3 pagesReflection Homophone 2api-356065858No ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Cushman Wakefield - PDS India Capability Profile.Document37 pagesCushman Wakefield - PDS India Capability Profile.nafis haiderNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Music 7: Music of Lowlands of LuzonDocument14 pagesMusic 7: Music of Lowlands of LuzonGhia Cressida HernandezNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- KPMG Inpection ReportDocument11 pagesKPMG Inpection ReportMacharia NgunjiriNo ratings yet

- MODULE+4+ +Continuous+Probability+Distributions+2022+Document41 pagesMODULE+4+ +Continuous+Probability+Distributions+2022+Hemis ResdNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 Computer ScienceDocument3 pagesUnit 3 Computer ScienceradNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- 2-Port Antenna Frequency Range Dual Polarization HPBW Adjust. Electr. DTDocument5 pages2-Port Antenna Frequency Range Dual Polarization HPBW Adjust. Electr. DTIbrahim JaberNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- TOGAF 9 Foundation Part 1 Exam Preparation GuideDocument114 pagesTOGAF 9 Foundation Part 1 Exam Preparation GuideRodrigo Maia100% (3)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- PROF ED 10-ACTIVITY #1 (Chapter 1)Document4 pagesPROF ED 10-ACTIVITY #1 (Chapter 1)Nizelle Arevalo100% (1)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Service and Maintenance Manual: Models 600A 600AJDocument342 pagesService and Maintenance Manual: Models 600A 600AJHari Hara SuthanNo ratings yet

- Column Array Loudspeaker: Product HighlightsDocument2 pagesColumn Array Loudspeaker: Product HighlightsTricolor GameplayNo ratings yet

- Reg FeeDocument1 pageReg FeeSikder MizanNo ratings yet

- Pradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyan (PMGDISHA) Digital Literacy Programme For Rural CitizensDocument2 pagesPradhan Mantri Gramin Digital Saksharta Abhiyan (PMGDISHA) Digital Literacy Programme For Rural Citizenssairam namakkalNo ratings yet

- Experiences from OJT ImmersionDocument3 pagesExperiences from OJT ImmersionTrisha Camille OrtegaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- John Hay People's Alternative Coalition Vs Lim - 119775 - October 24, 2003 - JDocument12 pagesJohn Hay People's Alternative Coalition Vs Lim - 119775 - October 24, 2003 - JFrances Ann TevesNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- AFNOR IPTDS BrochureDocument1 pageAFNOR IPTDS Brochurebdiaconu20048672No ratings yet

- Oracle Learning ManagementDocument168 pagesOracle Learning ManagementAbhishek Singh TomarNo ratings yet

- GIS Multi-Criteria Analysis by Ordered Weighted Averaging (OWA) : Toward An Integrated Citrus Management StrategyDocument17 pagesGIS Multi-Criteria Analysis by Ordered Weighted Averaging (OWA) : Toward An Integrated Citrus Management StrategyJames DeanNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Main Research PaperDocument11 pagesMain Research PaperBharat DedhiaNo ratings yet

- Break Even AnalysisDocument4 pagesBreak Even Analysiscyper zoonNo ratings yet

- Riddles For KidsDocument15 pagesRiddles For KidsAmin Reza100% (8)

- Memo Roll Out Workplace and Monitoring Apps Monitoring Apps 1Document6 pagesMemo Roll Out Workplace and Monitoring Apps Monitoring Apps 1MigaeaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Neuropsychological Deficits in Disordered Screen Use Behaviours - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument32 pagesNeuropsychological Deficits in Disordered Screen Use Behaviours - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisBang Pedro HattrickmerchNo ratings yet

- Mazda Fn4A-El 4 Speed Ford 4F27E 4 Speed Fnr5 5 SpeedDocument5 pagesMazda Fn4A-El 4 Speed Ford 4F27E 4 Speed Fnr5 5 SpeedAnderson LodiNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)