Professional Documents

Culture Documents

AfrJPaediatrSurg719-4907266 133752

Uploaded by

pawitrajayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

AfrJPaediatrSurg719-4907266 133752

Uploaded by

pawitrajayaCopyright:

Available Formats

[Downloaded free from http://www.afrjpaedsurg.org on Monday, August 17, 2015, IP: 202.80.215.

134]

Original Article

Operative management of typhoid ileal perforation in

children

Ali Nuhu, Samuel Dahwa1, Abdulkarim Hamza1

INTRODUCTION

ABSTRACT

Background: Intestinal perforation resulting from

complicated typhoid fever still causes high morbidity

and mortality. The purpose of the present study is to

evaluate the outcome of its surgical management in

Nigerian children. Materials and Methods: Emergency

laparotomy and repair of the ileum was performed on

46 children with typhoid ileal perforation at the Federal

Medical Centre (FMC), Azare, Nigeria, between January

2004December 2008. This was followed by copious

peritoneal lavage with warm normal saline and mass

closure of the abdomen. Results: There were 28

(60.86%) boys and 18 (39.13%) girls, with a mean age

of 9.5 3.22 (range, 15 months15 years). Abdominal

pain (45), fever (44), and abdominal distention (36) were

the most common presenting symptoms and majority

of the patients (36) perforated within 14 days of illness.

Solitary ileal perforations were the most common

pathology, found in 31 (67.4%) cases. Simple closure

of the perforations after debridement of the edges was

the most frequent operative procedure performed. A

total of 21 patients had one or more complications which

included wound infection (21), postoperative fever (16),

and wound dehiscence (6). Postoperative anaemia

was a problem in 23 (50%) patients. The mortality rate

was (13) 28.3%. The mean duration of hospital stay for

survivors was 22.9 12.3 (range, 646 days). This was

not significantly affected by the location or number of

perforations on the ileum. Conclusions: The clinical

course of typhoid ileal perforation may be different for

the very young. The typically high rate of complications

can be reduced if operation is undertaken earlier.

Solitary ileal perforations can be managed safely with

simple closure.

Key words: Children, management outcome, typhoid

ileal perforation

PMID: *******

DOI: 10.4103/0189-6725.59351

Department of Surgery, University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital,

PMB 1414 Maiduguri, Borno State, 1Department of Surgery, Federal

Medical Centre, Azare, Bauchi State, Nigeria

Address for correspondence:

Dr. Ali Nuhu,

Department of Surgery, University of Maiduguri Teaching Hospital,

PMB 1414, Maiduguri, Nigeria.

E-mail: nuhualinvwa@yahoo.com

African Journal of Paediatric Surgery

Intestinal perforation resulting from complicated

typhoid fever is a continuing challenge for the

surgeons practicing in an endemic area, because of

the high morbidity and mortality rates associated

with its operative management.[1] Salmonella typhi

and paratyphi infection (causing typhoid fever), is a

serious systemic disease in developing countries and in

countries where unhealthy environmental conditions

prevail. Intestinal perforation, the most common in

the ileum, is the most serious complication of typhoid

fever, with mortality rates ranging between 2060% in

the West African subregions.[1-3] In the endemic areas,

children below the age of 15 years account for more

than 50% of the intestinal perforation cases, with higher

mortality in them than the adult population.[4-6] The

reasons for these high mortality rates and postoperative

complications are, continuing severe peritonitis,

septicaemia, malnutrition, fluid, and electrolyte

derangements. It is agreed that surgical intervention to

seal the source of continuing peritoneal contamination

is the treatment modality with the best outcome, but the

operative technique of choice is not settled. We have

managed 46 children with typhoid ileal perforation

mainly by excision and simple closure followed by

copious peritoneal lavage after adequate resuscitation.

This study reviews the pattern of disease and outcome

of such management in a government referral hospital

in Northeast Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In a retrospective study, children with typhoid intestinal

perforation were identified from the hospital records

of all patients with intraoperative diagnosis of typhoid

perforation treated by the General Surgery Unit of

the Federal Medical Centre, Azare, from January

2004-December 2008. Relevant data regarding clinical

diagnosis, investigations, treatment, and outcome were

obtained from the operating theatre register and other

medical records. Descriptive data were analysed using

the SPSS version 15 for windows (SPSS, Chicago,- IL,

US) and presented in statistical Tables.

January-April 2010 / Vol 7 / Issue 1

[Downloaded free from http://www.afrjpaedsurg.org on Monday, August 17, 2015, IP: 202.80.215.134]

Nuhu, et al.: Operative management of typhoid ileal perforation in children

RESULTS

There were 46 children [28 (60.8%) boys and 18 (39.1%)

girls], with intraoperative diagnosis of typhoid ileal

perforation during the study period. Their mean age was

9.5 3.22 (range, 15 months- 15 years); and male: female

ratio was 1.5:1. Also, 36 (76.1%) patients were between

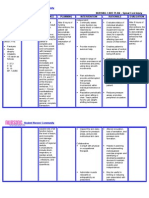

the age range of 915 years [Table 1]. There were 4

(8.7%) children below the age of five years. Almost all

the patients presented with abdominal pain, fever, and

features of peritonitis. The mean time lapse between

onset of symptoms of perforation and presentation to

hospital was 72.44 9.33 hours, (range, 24168). A

total of 44 (95.6%) patients had fever, 36 (78.3%) had

abdominal distention, 25 (54.3%) had vomiting, and

23 (50%) had constipation [Table 2]. Of the 41 patients

recorded, 21 (51.2%) perforated within the first seven

days of illness, 15 (36.6%) within the second week,

and 5 (12.2%) within the third week of illness. Plain

chest and abdominal radiographs were available for 31

(67.4%) patients with 16 (51.6%) showing free gas under

the diaphragm. The main electrolyte derangements were

hypokalaemia and raised serum urea in 13 (28.3%)

patients respectively. The packed cell volume (PCV)

was lower than 30% in 37 (80.4%) children. The widal

test was done in only 5 (10.8%) patients with the titre

higher than 1:160 in all of them. Blood cultures were

not done in any of the patients. A total of 24 (52.2%)

patients had surgery within 24 hours of presentation

to hospital and the rest 16 (34.7%) were operated after

24 hours of admission. The mean time from admission

to laparotomy was 9.4 hours (range, 624). The main

resuscitative measures in all the patients involved

correction of fluid and electrolyte derangements and

giving of pareneteral antibiotics. Those with PCVs below

30% had preoperative blood transfusion. The abdomen

was entered through a transverse subumbilical incision

for those who were five years and below (N = 4), and a

midline incision (long or subumbilical), for the others.

There were 76 ileal perforations in all, (mean = 1.65),

31 (67.4%) of which were single point [Figure 1]. Also,

5 (10.8%) patients had two perforations, another 5

(10.8%) had three, and 3 (6.5%) had four perforations

[Table 3]. There were no caecal perforations. The

highest number of ileal perforations in a single patient

was 14. The mean estimated size of the perforations

was 23.35 13.46 mm (range, 1080). Significant

faecal peritonitis was seen in all the patients with

moderate to massive soilage documented in 32 (69.6%)

of them. Eight (17.4%) patients had mild peritoneal

soilage. The main operative procedure was simple

two-layered transverse closure after a circumferential

excision of the perforation edges in 38 (82.6%) patients

and wedge resection in 1 (2.2%) patient. Six (13%)

patients had segmental ileal resection and primary

anastomosis; while one 8-year-old patient with multiple

ileal perforations, the most distal within 5 cm of the

ileocaecal junction (ICJ), had right hemicolectomy and

Table 1: Age and sex distribution of 46 children with

typhoid ileal perforation

Age (years)

14

58

912

1315

Total

Males

Females

Frequency (%)

4

4

11

10

29 (63.04)

0

3

6

8

17 (37.00)

4 (8.7)

7 (15.2)

17 (37)

18 (39.1)

46 (100)

Six hundred and seventy children were treated for typhoid fever, giving a perforation

rate of 6.8%.

Table 2: Clinical features

Presenting features

Abdominal pain

Fever

Abdominal tenderness

Abdominal distention

Vomiting

Constipation

Diarrhoea

10

January-April 2010 / Vol 7 / Issue 1

Features (%)

45 (97.8)

44 (95.7)

42 (91.3)

36 (78.3)

25 (54.3)

23 (50)

12 (26.1)

Figure 1: Typical single perforation of the terminal ileum due to typhoid fever

in a 10-year-old girl. Note the antemesenteric location and faecal peritonitis

Table 3: Distribution of number of perforations as it

relates to mortality

No. of perforations

1

2

3

4

5

14

Total

Frequency (%)

31 (67.4)

5 (10.8)

5 (10.8)

3 (6.5)

1 (2.2)

1 (2.2)

87 (100)

Mortality No. (%)

8 (25.8)

2 (40)

1 (20)

1 (33.3)

0 (0)

1 (100)

13 (28.3)

NB: There were a total of 87 ileal perforations. The highest number of perforations in

a single child was 14. The overall mortality rate was 28.3%.

African Journal of Paediatric Surgery

[Downloaded free from http://www.afrjpaedsurg.org on Monday, August 17, 2015, IP: 202.80.215.134]

Nuhu, et al.: Operative management of typhoid ileal perforation in children

ileotransverse anastomosis. Multiple adhesions were

noticed and lysed in 17 (36.9%) patients. The mean

estimated distance of the most distal ileal perforation

from the ICJ was 20.23 10.34 cm (range, 560).

Out of 37 documented patients, 19 (51.3%) had their

most dital perforations within 1020 cm of the ICJ.

The most common postoperative complications were:

wound infection 21 (%), postoperative fever 16 (%),

and anaemia 38 (%) [Table 4]. Eight (21.1%) of the 38

patients had simple closure, and 1 (16.7%) of the six had

segmental ileal resection reperforated within 4 to 9 days

(mean, 5.342.89) postoperatively, and reexploration

was done for four patients of which one survived. The

remaining five were managed conservatively of which

two survived. The overall mortality was 13 (28.3%).

Death occured 36 hours to 14 days (mean, 6.25.4

days) postoperatively from septic complications and

multiple organ failure. The mean duration of hospital

stay for survivors was 22.8912.34 days (range, 646).

The mean duration of follow-up was 4.839.36 weeks

(range, 255).

DISCUSSION

Typhoid ileal perforation is frequently seen among

children in our environment. Over this study period,

children aged 15 years and younger constituted 55.4%

of all cases. This is in keeping with earlier reports

from Nigeria where the paediatric age group accounted

for more than half the cases of typhoid intestinal

perforation. [5,6] In one of the report from Western

Nigeria[7] and India,[11] however, typhoid perforation

was the most common in the age group of 2130

years. There was a slight male preponderance (a male

female ratio of 1.7:1); similar to previous series.[6,8] The

prognosis of typhoid ileal perforation still remains

poor, with an overall mortality in this study of 28.3%,

in keeping with most previously reported series in the

tropical environment, including West Africa.[16] We

found, as previously reported, that the perforations are

the most common in the terminal ileum and survivors

were faced with wound infection and high rates of

wound dehiscence and enterocutaneous fistulae.[9]

Table 4: Postoperative complications

Postoperative complications

Wound infection

Postoperative fever

Reperforation

Wound dehiscence

Enterocutaneous fistula

Chest infection

Postoperative adhesions

Intraabdominal abscess

African Journal of Paediatric Surgery

Frequency (%)

21 (45.6)

16 (34.7)

9 (19.7)

6 (13)

4 (8.7)

4 (8.7)

3 (6.5)

1 (2.2)

Symptoms and signs of typhoid ileal perforation in

Nigerian children are not different from those in

other geographical areas,[10,11] with diarrhoea and fever

more prominent in those below five years of age. The

under five also have atypical features of generalised

peritonitis and it may not be easy to make a diagnosis

of peritonitis in them with certainty. Therefore, a high

index of suspicion is needed for a diagnosis in this

age group as demonstrated by other workers.[12] The

youngest child affected by typhoid ileal perforation

in our series was 15 months old; similar to one year[13]

and two years[14] in earlier reports. A report from

Zaria,[5] North Central Nigeria, recorded an incidence

in a two-month-old infant. This is an unusual finding

and may be due to contaminated expressed breast milk

among other possibilities. The older children exhibit

classical features of peritonitis in over 90% of cases,

supporting the diagnosis.[12] Ileal perforations occurred

within the first week of typhoid fever in over 50% of

our patients, with reference to earlier reports from

Northern Nigeria[2] and other parts of tropical Africa.[15]

This is in contrast to the classical description of three

weeks, ten days,[16] or two weeks[17] in other reports.

This may be due to a more virulent strain of Salmonella

typhi among West Africans, coupled with increased

hypersensitivity reaction in the Peyers patches in this

subregion, where the perforation rate is higher than

other endemic areas.[1] Late presentation, with mean

estimated perforation duration of four days (range,

27), and delay in operation (over 30% operated after

24 hours of presentation to hospital), were responsible

for the high mortality and morbidity in all age groups

as reported by other series.[15,18]

The need for aggressive fluid resuscitation and

correction of electrolyte derangements and anaemia;

together with the choice of a suitable antibiotic

combination is crucial to surgical outcome. The antibiotic

protocol that has been used over the years included:

chloramphenicol, gentamycin, and metronidazole;

which are given parenterally at diagnosis and continued

for seven days before conversion to oral preparations of

chloramphenicol and metronidazole. The rationale is to

cover for not only the Salmonella organism but also for

anaerobes and gram negative coliforms. The emergence

of chloramphenicol resistant, Salmonellae, has led to

the use fluoroquinolones (for example, ciprofloxacin),

or third generation cephalosporins.[19] To be certain that

the perforation on the ileum is due to typhoid enteritis,

a positive blood, stool or urine culture is necessary.

However, the yield for blood culture in a patient with

typhoid intestinal perforation is low, ranging from

334%, [3,20] in some reports. Higher yields of the

Salmonella organism is obtained from cultures of the

January-April 2010 / Vol 7 / Issue 1

11

[Downloaded free from http://www.afrjpaedsurg.org on Monday, August 17, 2015, IP: 202.80.215.134]

Nuhu, et al.: Operative management of typhoid ileal perforation in children

perforation edges, bone marrow, or peritoneal aspirates;

but this is often not possible and even when they are

done the results do not significantly alter the operative

treatment given to the patient. The classical disposition

of the typhoid perforation in the longitudinal axis of

the ileum and on the antemesenteric border with an

antecedent history of prolonged febrile illness in a child,

who did not respond to antimalarials, is enough to make

a conclusion as to the aetiology of the perforation. A

plain abdominal or chest radiograph with free air under

the diaphragm is a fairly frequent but variable finding

signifying perforated hollow viscus, but its absence does

not exclude the diagnosis.

The presence of single ileal perforations in majority

(76.4%) of our patients is consistent with other

reports [16] [Figure 1], and moderate to massive

peritoneal contamination favoured the development

of septic complications, such as wound infection,

wound dehiscence, residual intraabdominal abscesses,

and enterocutaneous fistulae, in those patients who

survived. [18] We found multiple perforations with

massive peritoneal soilage in 15 (32.6%) patients.

Prompt surgery after adequate resuscitation, is the

treatment of choice for typhoid perforation; this has

considerably reduced mortality from 3060%[13] to

approximately 6.8% in a recent series.[21] Many surgical

techniques have been used, ranging from simple

peritoneal drainage under local anaesthesia in moribund

patients,[20,22] excision of the edge of the ileal perforation,

and simple transverse closure in two layers; as done for

majority of our patients, segmental ileal resection and

primary anastomosis especially in multiple perforations

or right hemicolectomy where the caecum is involved.

There are conflicting results of the outcome of these

widely practiced techniques. Whereas, better results are

reported with simple closure, in many series;[3,20] others

favour segmental ileal resection and anastomosis.[23,24]

Those that favour simple closure argue, that in such very

ill patients any prolonged procedure may jeopardise the

outcome and that the ileum affected by typhoid fever,

take sutures well without cutting through. This was the

experience of the authors. We carried out segmental

resection and primary anastomosis only when there

were multiple perforations that were in close range

and when the caecum was involved. But any operative

technique that is carried out in good time, and allows

for a swift clearing of peritoneal contamination by a

copious peritoneal lavage is the most likely to give the

best outcome.

Our practice in managing these children is a simple

closure of the perforation, peritoneal lavage with warm

12

January-April 2010 / Vol 7 / Issue 1

normal saline, and closure of the abdominal wall with

drainage. Ceftriazone, metronidazole, and gentamicin

are given perioperatively to cover for the Salmonella,

gram negative organisms, and coliforms, respectively.

The side-effects of the quinolone ciprofloxacin on the

growing cartilage of the child usually make it a second

choice in our practice, except when the benefit clearly

outweighs this risk.

Mortality rate remains high after surgical treatment

for typhoid intestinal perforation; 28.3% in this

study, compare favourably with similar studies from

Nigeria[5,6] and the West African subregion.[3,9] Mortality

is related to endotoxaemia, septicaemia, and multiple

organ failure. There have been reports of very high

mortality, [16] but with early presentation, timely

surgery, and improvement in critical care, this can be

reduced drastically. Exceptionally, low mortality rates of

35% have been reported[25,26] previously. The reason for

the high mortality is multifactorial. In our experience,

late presentation, delay in diagnosis, and inappropriate

or partial treatment of typhoid fever were the main ones.

In conclusion, typhoid ileal perforation in children has

a poor prognosis in our environment. Late presentation,

delayed operation, faecal peritoneal contamination, and

postoperative faecal fistulae are the factors that have

adverse effects on survival. Most deaths occurred during

the early postoperative period, with survivors having

a prolonged hospital stay. There should be a deliberate

community drive towards preventive measures; by

health education, improvement in potable water supply,

sewage disposal, and personal hygiene to stamp out this

public health menace.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank all the consultants and resident doctors of the

Department of Surgery, Federal Medical Centre, Azare for their

cooperation during the period of this study. We appreciate

the contribution of the Nurses on the Surgical and Paediatric

Surgical wards of the Hospital and the Medical records staff

for extracting the folders.

REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Archampong EQ. Typhoid ileal perforation: why such mortality. Br

J Surg 1976;63:317-21.

Akoh JA. Prognostic factors in typhoid perforation. East Afr J Med

1992;70:18-21.

Mock CN, Amaral J, Visser LE. Improvement in survival from

typhoid ileal perforation: result of 221 operative cases. Ann Surg

1992;215:244-9.

Ugwu BT, Yiltok SJ, Kidmas AT, Opaluwa AS. Typhoid intestinal

perforation in north central Nigeria. West Afr J Med 2005;24:1-6.

Ameh EA. Typhoid ileal perforation in children: a scourge in

African Journal of Paediatric Surgery

[Downloaded free from http://www.afrjpaedsurg.org on Monday, August 17, 2015, IP: 202.80.215.134]

Nuhu, et al.: Operative management of typhoid ileal perforation in children

6.

7.

8.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

developing countries. Ann Trop Paedtr 1999;19:267-72.

Uba AF, Chirdan LB, Ituen AM, Mohammed AM. Typhoid intestinal

perforation in children: a continuing scourge in a developing country.

Paed Surg Int 2007;23:33-9.

Ajao OG. Typhoid perforation: factors affecting mortality and

morbidity. Int Surg 1982;4:317-9.

Butler T, Knight J, Nath SK, Speelman P, Roy SK, Azao MA. Typhoid

fever complicated by intestinal perforation: a persisting fatal outcome

requiring surgical management. Rev Infect Dis 1985;7:244-56.

Abatanga FA, Wiafe-Addai BB. Postoperative complications after

surgery for typhoid perforation in children in Ghana. Paediatr Surg

Int 1998;14:55-8.

Atamanalp SS, Aydinli B, Ozturk G, Oren D, Basoglu M, Yildirgan

MI. Typhoid intestinal perforation: twenty-six year experience. World

J Surg 2007;31:1883-8.

Talwar S, Sharma KR, Mittal DK, Prasad P. Typhoid enteric

perforation. Aust N Z J Surg 1997;67:351-3.

Ekenze SO, Ikefuna AN. Typhoid intestinal perforation under 5 years

of age. Ann Trop Paediatr 2008;28:53-8.

Ekenze SO, Okoro PE, Amah CC, Ezike HA, Ikefuna AN. Typhoid

ileal perforation: Analysis of morbidity and mortality in 89 children.

Niger J Clin Pract 2008;11:58-62.

Lizaralde E. Typhoid perforation of the ileum in children. J Paediatr

Surg 1981;16:1012-6.

Archampong EQ, Tandoh JFK, Nwako FA, da Rocha-Afodu JT, Foli

AK, Darko R, et al. Small and large intestine (including rectum and

anus). In: Badoe EA, Archampong EQ, da Rocha-Afodu JT, editors.

Principles and practice of surgery including pathology in the tropics.

3rd ed. Accra: Ghana Publishing Company Tema; 2000. P. 620-32.

16. Kizilcan F, Tanyel FC, Buyukpamukcu N, Hicsonmez A.

Complications of typhoid fever requiring laparotomy during

childhood. J Paediatr Surg 1993;28:1490-3.

17. Keenan JP, Hadley GP. The surgical management of typhoid

perforation in children. Br J Surg 1984;71:928-9.

18. Adesunkanmi AR, Ajao OG. The prognostic factors in typhoid ileal

perforation: A prospective study of 50 patients. J R Coll Surg Edin

1997;42:395-9.

19. Kabra SK, Madhulika, Talati A, Soni N, Patel S, Modi RR. Multi drug

resistant typhoid fever. Trop Doct 2000;30:195-7.

20. Khana AK, Misra MK. Typhoid perforation of the gut. Postgrad Med

J 1984;60:523-5.

21. Karmacharya B, Sharma VK. Results of typhoid perforation

management: experience in Bir Hospital, Nepal. Kathmandu Univ

Med J (KUMJ) 2006;4:22-4.

22. Kim JP, Oh SK, Jarret F. Management of ileal perforation due to

typhoid fever. Am J Surg 1976;181:88-91.

23. Shah AA, Wani KA, Wazir BS. The ideal treatment of typhoid enteric

perforation- resection anastomosis. Int Surg 1999;84:35-8.

24. Ameh AE, Dogo PM, Attah MM, Nmadu PT. Comparison of three

operation s for typhoid perforation. Br J Surg 1997;4:558-9.

25. Vargas M, Penne A. Perforated viscera in typhoid fever: a better

prognosis for children. J Paediatr Surg 1975;10:531.

26. Santillana M. Surgical complications of typhoid fever: enteric

perforation. World J Surg 1991;15:170.

Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: None.

Author Help: Online submission of the manuscripts

Articles can be submitted online from http://www.journalonweb.com. For online submission, the articles should be prepared in two files (first

page file and article file). Images should be submitted separately.

1)

2)

3)

4)

First Page File:

Prepare the title page, covering letter, acknowledgement etc. using a word processor program. All information related to your identity

should be included here. Use text/rtf/doc/pdf files. Do not zip the files.

Article File:

The main text of the article, beginning with the Abstract to References (including tables) should be in this file. Do not include any information

(such as acknowledgement, your names in page headers etc.) in this file. Use text/rtf/doc/pdf files. Do not zip the files. Limit the file size

to 1 MB. Do not incorporate images in the file. If file size is large, graphs can be submitted separately as images, without their being

incorporated in the article file. This will reduce the size of the file.

Images:

Submit good quality color images. Each image should be less than 2048 kb (2 MB) in size. The size of the image can be reduced by

decreasing the actual height and width of the images (keep up to about 6 inches and up to about 1200 pixels) or by reducing the quality of

image. JPEG is the most suitable file format. The image quality should be good enough to judge the scientific value of the image. For the

purpose of printing, always retain a good quality, high resolution image. This high resolution image should be sent to the editorial office at

the time of sending a revised article.

Legends:

Legends for the figures/images should be included at the end of the article file.

African Journal of Paediatric Surgery

January-April 2010 / Vol 7 / Issue 1

13

You might also like

- Doll-Cupid P MsDocument5 pagesDoll-Cupid P MsMuhammad Bahrian ShalatNo ratings yet

- 29Document3 pages29pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- Definition Fracture BedahhhhhhDocument6 pagesDefinition Fracture BedahhhhhhpawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 1 PembukaanDocument3 pages1 PembukaanIsmail YusufNo ratings yet

- 28Document2 pages28pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 1475 2875 8 134Document6 pages1475 2875 8 134pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- Kissing Dolls: Pattern: Notation Key ToolsDocument0 pagesKissing Dolls: Pattern: Notation Key ToolsmyyyyyrNo ratings yet

- Daftar PustakaDocument3 pagesDaftar PustakatamictrNo ratings yet

- Faktor-Faktor Risiko Yang Berpengaruh Terhadap Persalinan Dengan TindakanDocument135 pagesFaktor-Faktor Risiko Yang Berpengaruh Terhadap Persalinan Dengan TindakanRakhmat Ari Wibowo50% (2)

- Kissing Dolls: Pattern: Notation Key ToolsDocument0 pagesKissing Dolls: Pattern: Notation Key ToolsmyyyyyrNo ratings yet

- 1Document9 pages1Flavia LopesNo ratings yet

- 28Document2 pages28pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- Typhoid Fever Current Concepts.5Document7 pagesTyphoid Fever Current Concepts.5pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- Cinnamon bark oleoresin improves skin and bone collagen in aged ratsDocument7 pagesCinnamon bark oleoresin improves skin and bone collagen in aged ratspawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- Hahaha Aah AhahaaaDocument1 pageHahaha Aah AhahaaapawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- Hahaha Aah AhahaaaDocument1 pageHahaha Aah AhahaaapawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 25Document3 pages25pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 27 What Is Medical Professionalism?Document4 pages27 What Is Medical Professionalism?pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 26Document3 pages26pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 24Document3 pages24pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 27 What Is Medical Professionalism?Document4 pages27 What Is Medical Professionalism?pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 26Document3 pages26pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 24Document3 pages24pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- Di Susunoleh: Ratri Diana Sari 13700053 Putupartaanantama 13700055 Ida Ayugalih Pertiwi 13700057 Ida Bagus Putra Narendra 13700059Document4 pagesDi Susunoleh: Ratri Diana Sari 13700053 Putupartaanantama 13700055 Ida Ayugalih Pertiwi 13700057 Ida Bagus Putra Narendra 13700059pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 18Document3 pages18pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 17Document3 pages17pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 16Document3 pages16pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- 31Document3 pages31pawitrajayaNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Department of Genetics: Covid-19 RT PCRDocument1 pageDepartment of Genetics: Covid-19 RT PCRAshwin ShajiNo ratings yet

- Functions of Parotid GlandDocument32 pagesFunctions of Parotid GlandAsline JesicaNo ratings yet

- Edema LymphedemaDocument2 pagesEdema LymphedemaAsmat BurhanNo ratings yet

- OBGYN End of Rotation Exam OutlineDocument35 pagesOBGYN End of Rotation Exam OutlinehevinpatelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Profile and Outcome of Myasthenic CrisisDocument13 pagesClinical Profile and Outcome of Myasthenic CrisissyahriniNo ratings yet

- Alzheimer'S Disease Definition: Signs and SymptomsDocument4 pagesAlzheimer'S Disease Definition: Signs and SymptomsMauren DazaNo ratings yet

- 12 Tips For Bedside TeachingDocument4 pages12 Tips For Bedside Teachingbayu100% (1)

- Lesson Plan On Home Visit JKSDocument4 pagesLesson Plan On Home Visit JKSjatheeshNo ratings yet

- DOH STANDARDS (Indicators) For LEVEL 2 HOSPITALDocument55 pagesDOH STANDARDS (Indicators) For LEVEL 2 HOSPITALMOHBARMM PlanningStaffNo ratings yet

- Progyluton-26 1DDocument16 pagesProgyluton-26 1DUsma aliNo ratings yet

- 2 Conversion of Iv To PoDocument27 pages2 Conversion of Iv To PoSreya Sanil100% (1)

- Contoh Soal UKNiDocument4 pagesContoh Soal UKNiNurhaya NurdinNo ratings yet

- Hepatic Disease in PregnancyDocument37 pagesHepatic Disease in PregnancyElisha Joshi100% (1)

- Philippine Nursing Act of 2002Document22 pagesPhilippine Nursing Act of 2002Hans TrishaNo ratings yet

- Full Text 01Document44 pagesFull Text 01ByArdieNo ratings yet

- Simulation Program For Clinical Performance Improvement: Improving Clinical Care and Patient Safety Through SimulationDocument11 pagesSimulation Program For Clinical Performance Improvement: Improving Clinical Care and Patient Safety Through SimulationiloilocityNo ratings yet

- Flap Approaches in Plastic Periodontal and Implant Surgery: Critical Elements in Design and ExecutionDocument15 pagesFlap Approaches in Plastic Periodontal and Implant Surgery: Critical Elements in Design and Executionxiaoxin zhangNo ratings yet

- Cleveland Doctor Disciplined by Medical BoardDocument6 pagesCleveland Doctor Disciplined by Medical BoarddocinformerNo ratings yet

- CGMP GuidelinesDocument4 pagesCGMP GuidelinesMohan KumarNo ratings yet

- Sanction Terms Loan DetailsDocument4 pagesSanction Terms Loan Detailsinfoski khan100% (1)

- BPH - PlanDocument5 pagesBPH - PlanSomesh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Additional Vacancies at CHCs in Health and Family Welfare Services For One Year Government ServicesDocument5 pagesAdditional Vacancies at CHCs in Health and Family Welfare Services For One Year Government ServicesBhavvNo ratings yet

- Guidance To The Internaitonal Medical Guide For Ships 3rd EdDocument14 pagesGuidance To The Internaitonal Medical Guide For Ships 3rd EdSaurabh YadavNo ratings yet

- NCPDocument2 pagesNCPsphinx809100% (2)

- Carboprost Drug StudyDocument3 pagesCarboprost Drug StudyAjay SupanNo ratings yet

- MTLB Debate PRODocument3 pagesMTLB Debate PRORHODA MAE CAPUTOLNo ratings yet

- What Is Infusion Pump?Document4 pagesWhat Is Infusion Pump?BMTNo ratings yet

- Secondary Survey for Trauma PatientsDocument18 pagesSecondary Survey for Trauma PatientsJohn BrittoNo ratings yet

- Medical skills checklist for nursesDocument5 pagesMedical skills checklist for nursesHussain R Al-MidaniNo ratings yet

- Pathophysiology of Shock Sepsis and Organ Failure PDFDocument1,179 pagesPathophysiology of Shock Sepsis and Organ Failure PDFNotInterested100% (1)