Professional Documents

Culture Documents

121 91 1 PB

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

121 91 1 PB

Copyright:

Available Formats

International Journal of Existential

Psychology & Psychotherapy

Baseball Fan Loyalty and the Pillars of Existence

C. Daniel Crosby

Doctoral Candidate

Brigham Young University

Introduction

The origins of existentialism are as nebulous as the theory itself, which, unlike most

theories of personality, is not a uniform philosophy of human behavior (Rychlak, 1981).

Perhaps fittingly, some of the forefathers of

this movement have themselves resisted being

labeled existentialists. Indeed, the movement

in general arose as a reaction to other schools

of psychology that fell into the common

error of distorting human beings in the very

effort of trying to help them (May & Yalom,

1989, p.363). Difficulties notwithstanding, I will attempt to give a brief illustration

of the history of existentialism, as well as a

basic outline of its application to personality

theory. This outline will serve as a conceptual

framework whereby elements of baseball fan

participation can be examined in light of their

relevance to existential psychological theory.

Existentialism:

A Brief History

Soren Kierkegaard, a Danish philosopher

(1813-1855) is often credited as the father of

existentialism (Rychlak, 1981). Kierkegaard

is most well known for his criticism of the

highly intellectualized rationalist philosophy

of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (17701831). Kierkegaard reacted against Hegels

philosophy, positing that the human condition could not reasonably studied without

www.ExistentialPsychology.org

Volume 2, Number 2

June, 2008

examining the spontaneous, emotional, and

unpredictable elements of life. Some time

after the initial contributions of Kierkegaard, a new wave of theorists, most of whom

worked closely with Husserl, continued to

advance existential ideas. Although they did

not agree on some important points, each of

these theorists focused on concepts such as

being, ontology, and existence that have come

to define what can be loosely referred to as

the existential movement (Rychlak, 1981).

During the 1940s and 1950s, a number of

psychologists and psychiatrists in Europe,

began to adopt some of the ideas of the aforementioned thinkers and attempted to apply

them to their studies of human behavior.

These individuals believed that the prevailing

psychological ideas of the day, such as Freudian drive theory and Jungian archetypes were

overly simplistic and reductionistic, and tended to overlook important aspects of the person of the client in their attempts to explain

them. It was the desire of these mental health

professionals to not fall into the common

error of distorting human beings in the very

effort of trying to help them (May & Yalom,

1989, p. 363). The writings and theorizing of

modern-day existential psychologists such as

May, Yalom, and Frankl, continues the focus

on broad themes such as death, anxiety, and

meaning, while attempting to recognize and

respect the uniqueness and unpredictability of

each client.

Existential Psychological

Theory A Brief Overview

As previously mentioned, existential theory

resists pigeonholing clients, and is fundamentally opposed to some reductionistic and

1

International Journal of Existential

Psychology & Psychotherapy

mechanistic elements of psychological practice as currently constituted (e.g. treatment

manuals). Thus, it stands to reason that existential theory is difficult to standardize and

does not rely on formulaic conceptions of human behavior. Although existential psychology rests on common theoretical underpinnings rather than a specific set of techniques,

Irvin Yalom attempts to describe some universal elements of this theory in his seminal

work Existential Psychotherapy (1981). This

work is the closest approximation of a uniform description of an approach that resists

uniformity at its core. As this book has attempted to standardize this sometimes ethereal worldview, I will use the basic structure,

as presented by Yalom, as a framework from

which to make comparisons to baseball fan

participation. To summarize the basic framework of existential personality theory as proposed by Yalom (1981), the conflict between

an individual and the givens of existence accounts in large part for their adjustment and

satisfaction with life. Yalom describes four

givens or ultimate concerns that each of us

most confront and come to terms with; death,

isolation, freedom, and meaninglessness. It

is through confrontation with and resolution

of these conflicts that an individual begins to

live a meaningful existence. In the following

sections, I will give a brief description of each

of these four existential pillars, and use this

frame of reference to draw conclusions about

the existential significance of baseball fan

participation and team loyalty.

Death

Death is perhaps the most obvious and most

important of the four existential givens. Like

all living beings, humans are subject to death,

www.ExistentialPsychology.org

Volume 2, Number 2

June, 2008

despite our wish to live and persist in our own

being. However, unlike other living things, we

have an awareness of the brevity and fragility of our lives, a concept which can either

lead us to live more fulfilled lives, or to cope

maladaptively with the inevitability of our

own demise. Our simultaneous wish to live

and knowledge that we will someday die, has

serious negative implications if handled incorrectly. Existential theorists believe that we

erect defenses against death awareness, and

that some of these defenses are denial-based,

pathological and may have consequences on

character development (May & Yalom, 1989).

Optimally, an individual will confront the imminence of their own death, and use this as a

boundary experience that will promote a life

more passionately and fully lived. As Yalom

points out in The Gift of Therapy (2002),

though the physicality of death destroys us,

the idea of death may save us (p. 126).

The relationship between death anxiety and

baseball fan participation may not be readily

apparent, however, a closer look at the literature shows some interesting correlations.

Ernest Becker, noted cultural anthropologist,

posits a number of ways in which we attempt

to deal with the anxiety of our own death in

his Pulitzer Prize winning book, The Denial of Death (1987). First, Becker contends

that we attempt to live on in symbolic ways

through our collective allegiance to a group

that shares a common goal. Historically,

examples of such groups have been countries, political groups, and religious groups

that share a common history, worldview, and

represent themselves in recognizable symbolic

ways. However, it is not difficult to see how

this same idea pertains to a baseball team.

Consider for instance, the Red Sox Nation;

International Journal of Existential

Psychology & Psychotherapy

these fans share a common history (of losing, for many years), common goals (beating the Yankees), and common symbols (red

and blue colors, B cap, etc) whereby they

can identify themselves as members of this

cohesive unit. As individuals ally themselves

with the Red Sox Nation, they transcend

the smallness and fragility of humanity in a

symbolic way, thereby becoming larger than

life. Allegiance to a given team also allows an

individual to pin their own mortality to the

perceived immortality of that organization.

The team has existed before, which gives the

individual a sense of tradition, and the team

will likely exist after he or she is gone, which

gives that individual a sense of belonging to

something permanent and transcendent.

Becker also asserts (1987) that aligning our

lives with something heroic is another way in

which we seek to thwart our nagging death

anxiety. By feeling a part of something that

seems to transcend the bounds of human

possibility, we delude ourselves into thinking that we can become something greater

than a mere mortal. Certainly, baseball is

full of heroism of sorts, and daily highlight

shows emphasize dramatic feats of athletic

accomplishment; eye-popping defensive

plays, and towering home runs. By focusing

on, and feeling part of, the accomplishments

of the athletically gifted and the powerful,

we assuage our fears about our puniness and

finitude. In this same vein, even the meanest

of professional baseball players is extremely

athletically gifted when compared to the

average baseball fan. Further, most players are

between the age of 20 and 40, with few playing after their late 30s. Associating with these

individuals as a fan, may allow someone to

ignore obvious indications of his or her own

www.ExistentialPsychology.org

Volume 2, Number 2

June, 2008

aging (e.g. thinning hair, wrinkles, etc) by

identifying with an image of a far more powerful, vibrant human being. Thus, by following

and idolizing the young, healthy, and athletically gifted, we are able to turn our eyes away

from other indications of our own mortality.

Finally, Becker (1987) postulates that one

final way that we seek to overcome our

natural fears of death is to conquer or defeat

someone else. Becker asserts that as we come

to dominate someone who is symbolically

different than us, we manifest, if only briefly,

our own superiority and invulnerability. In

so doing, we are able to set aside our anxiety

and fears about our temporality and physical

imperfections. The parallels to baseball here

are obvious, if our team is able to defeat the

opposing team, for a moment we are victorious and superior. This may, in part, explain the

proliferation of Yankees fans as compared to

fans of other teams. After all, if our goal is to

lose consciousness of our own vulnerability

by pairing ourselves with a powerful organization, it stands to reason that many would

choose a team with deep pockets and a bulging trophy case.

Isolation

Existential isolation, as conceptualized by

Yalom is fundamentally different than isolation as it is used in the vernacular. Existential

isolation refers to the fundamental, unbridgeable gulf that exists between human beings.

Simply put, the living and dying that each

of us do, must be done most fundamentally

alone (Yalom, 1981). Certainly, we can have

close interpersonal relationships and valuable

affiliations with clubs and other larger organizations that contribute to our happiness and

International Journal of Existential

Psychology & Psychotherapy

personal growth. But no matter how much we

are loved, or how close we are to a significant

other, at some point they cannot do our living

for us. May and Yalom explain the application

of this concept in their article, Existential

Psychotherapy, If one acknowledges ones

isolated situation in existence and confronts

it with resoluteness, one will be able to turn

lovingly toward others. If, on the other hand,

one is overcome with dread in the face of

isolation, one will not be able to turn toward

others, but instead will use others as a shield

against isolation (p.379).

This realization, much like the other givens,

is both empowering and frightening. On one

hand, being fundamentally our own entity

means that we are in charge of our destiny

in important ways. Conversely, fundamental

isolation means that the rocky road of life

must be faced alone at some level, when we

may most long for another to relieve us of our

cross. People sometimes react to the reality

of existential isolation by attempting to avoid

it. Most commonly this is seen in cases of

pathological neediness, a history of enmeshed

relationships, and sexual acting out. Sadly,

these attempts at fusing with others do not

relieve these individuals of their loneliness, as

they fail to address the fundamental reality of

our separateness.

Much as some individuals seek to overcome

their loneliness by becoming one with another person, a fan may seek to fight feelings

of isolation by becoming intensely loyal to

a preferred team. Indeed, membership has

its privileges, as a simple profession of allegiance gives the individual access to a large

body of like- minded individuals, a team full

of talented athletes, and most importantly, a

www.ExistentialPsychology.org

Volume 2, Number 2

June, 2008

context in which he or she undeniably belongs. Notice the word choice of a devout fan

who has recently watched his or her favorite

team win an important game. Typically the

chant is, We won! We won! The person has

so identified him or herself with the team,

that they actually give themselves some credit

in the victory. This perceived unity with the

team may be an attempt at overcoming what

the client may be sensing at a deep level; that

they are truly alone.

This is certainly not to suggest that all fan

behavior is an effort to overcome existential

isolation; only that fan loyalty is an effective way to join a large, pre-existing group of

individuals that is symbolically and teleologically unified. If done from a place of strength

and self-awareness, the rewards can be immense. If done as a clingy reaction to fear of

isolation, the results will likely be unsatisfactory. As mentioned earlier, the I of the fan

may quickly fade into the We of the team,

an occurrence that may have actual socialization benefits but may also serve as a sort of

faux intimacy. The relative healthiness or

unhealthiness of this behavior is dependent

on the fans level of involvement and how it

affects their interactions with the important

elements of their existence.

Freedom

Freedom, in the existential sense, is different than the freedom we typically speak of.

Typically, we do not think of freedom as a

source of anxiety. In America, freedom is

spoken of in reverent terms and is largely

seen as what undergirds the greatness of our

country. However, freedom in the existential

sense, refers to the groundlessness of our

International Journal of Existential

Psychology & Psychotherapy

existence, and our attendant responsibility to

create a meaningful worldview. As May and

Yalom state (1989), Freedom refers to the

fact that the human being is responsible for

and the author of his or her own world, own

life design, own choices and actions (p.377).

Simply put, life does not come with an instruction manual, which then makes it our

responsibility to mold and shape our lives in

meaningful ways. The anxiety that comes with

the realization of this freedom, can either

embolden us to move forward, proactively

shaping a world in which to operate, or can

be debilitating in that we realize that, in a real

sense, the weight of the world is upon us. As

Soren Kierkegaard famously said, Anxiety is

the dizziness of freedom.

As a reaction to the groundlessness of existence, people often cling to form and structure, commonly in the form of religious and

political ideologies or organizational structures. Much like a church, a political party, or

a life-philosophy; loyalty to an athletic organization gives an individual a stable point to

which they can anchor their existence. Like

all organizations, fans of a baseball team have

a culture, social norms, and a history. This

structure can offer a framework from which

to move about, and can assuage some of the

terror of being solely responsible for ones

own life construction. To some, the comparison of team loyalty to political or religious

loyalty may seem silly. However, one need

look no further than the soccer riots of South

America and Europe to understand that dedication to a team can be a visceral experience.

Wrapped up in support of a team are often

deeper- seated issues such as love of country

or place and long held family traditions. This

www.ExistentialPsychology.org

Volume 2, Number 2

June, 2008

attachment to groundedness is a natural

reaction to the amorphousness of existence,

and when done in moderation can be adaptive and health promoting. However, excessively dogmatic commitment to a philosophy

or organization can lead an individual to shirk

the responsibility of forming a worldview

from which to operate. Pathological overcommitment to an idea can also lead an individual

to devalue other ways of operating, which

can even lead to hostility (e.g. soccer riots,

religious wars) in the worse case scenario.

Part and parcel of our personal freedom is

the responsibility that comes with it to create a personality. Far different from more

biologically deterministic models of personality, existentialism proposes that each of us is

contextually agentic, meaning that we can

create a personality within the parameters

of certain contextual variables (e.g. genetic

endowments, culture). While this possibility heartening, it can also be daunting, as we

realize that we cannot wholly hide behind

faulty genes or bad parenting as excuses for

why we behave in certain ways. Again, given

the difficulty of this task, humanity has often

taken symbolic shortcuts en route to personality construction. For instance, owning

a Rolls Royce makes symbolic statements

about who we are that largely circumvent the

arduous process of from scratch personality

construction. If I own a Rolls Royce, others

may assume that I am intelligent, wealthy,

or industrious. Of course, they may also assume that I am pompous and frivolous, but

the point remains; we associate ourselves with

symbols and organizations that serve as heuristic shortcuts for making judgments about

our personalities and those of others we come

5

International Journal of Existential

Psychology & Psychotherapy

in contact with. In baseball, as in luxury car

ownership, the team we support says things

about the person we are and wish to be.

Bearing this in mind, as I adopt an affinity for

a given team and begin to take their symbols

upon myself, I send myself, and others meaningful clues about my personality. Consider

for instance, a fan of the St. Louis Cardinals.

As a fan, they may frequently wear the symbols of their chosen team (e.g. red hat with

StL logo), thereby associating myself with

a history, a place, and an attitude that I can

adopt en route to personality construction.

For instance, the Cardinals are the second

most decorated team in World Series history, and are often commended for having

a knowledgeable but amiable fan base. As

a fan, one can personally and symbolically

invest themself in these meanings and apply

them to their own life. Much as a devotee of a

religion, they can be comforted in their adoption of the attitudes and positive stereotypes

of a given organization. The groundlessness of

existence is effectively swallowed up in their

commitment to the meaningful scaffold provided by my team allegiance.

Meaninglessness

As Yalom states in his treatise on existential therapy (1981), we are meaning seeking

creatures born into a meaningless world. Each

of us needs a raison detre but life is largely

formless and allows us to create (or not create) a personal meaning that will guide our

own earthly travails. Perhaps no other existential psychotherapist has spoken as poetically and as powerfully about the power of

meaning as Viktor Frankl. Relating his experiences in the concentration camps of World

www.ExistentialPsychology.org

Volume 2, Number 2

June, 2008

War II, Frankl speaks to the power of the

human spirit when motivated by an overarching purpose in life (2000). Rather than giving

in to the absurd tragedy of his experience,

Frankl maintained personal meanings such as

his love of God, and his desire to teach future

generations that saw him through the terrors

of Auschwitz. Commonly repeating Nietschzkes words (as quoted in Frankl, 2000),

He that has a why to live can bear with

almost any how, Frankl became the living

embodiment of the power of aligning oneself

with something grander than oneself.

Fan dedication to a given team, may imbue

individuals with a sense of meaning and a

sense of being part of something grand. In

an age where commitment to traditional

organizations is thought to be on the decline, team loyalty may be the current secular

analogue of membership to a church or civic

organization. Further, fans can often feel

needed by the team, as a sort of tenth man.

Half-jokingly, fans may say that their team

lost because, I must not have been yelling

loud enough or because they missed an important game on television. While these fans

likely understand the limits of their own involvement at a rational level, their wish to be

needed and valued by the team may be very

real and powerful. This, paired with the meaning derived from being part of a larger whole,

may be powerful forces in the fans life. In an

existence where meaning may be hard to find,

the love of a baseball team may represent a

sort of prepackaged end to strive toward. In

closing, consider the Major League Baseball

slogan of a few years past, Major League

Baseball, I Live For This!, in reality, some of

us just may.

6

International Journal of Existential

Psychology & Psychotherapy

Volume 2, Number 2

June, 2008

Conclusion

Existential psychology, as delineated by

Yalom (1981) is the intellectual offspring of

existentialism, a philosophy that shares some

broad common concerns if no formally accepted structure. Existential psychological

theory states that much of human behavior

can be described and evaluated in terms of

four givens of existence: death, isolation,

meaninglessness, and freedom. Often applied

to examine maladaptive behaviors in clients,

these four pillars may be of use in examining

something as seemingly quotidian as baseball

fan team loyalties. In reality, baseball fan allegiance to a team may have great existential

significance, providing a means of ignoring

death anxiety and adopting preconstructed

personal meaning, among other things. This

phenomenon may be a secular analogue to

other, more commonly considered ways of

approaching the pillars of existence, such as

religious participation.

REFERENCES

Becker, E. (1987). The Denial of Death. New

York: Free Press.

Frankl, V. (2000). Mans Search for Meaning.

New York: Beacon Press.

May, R. & Yalom, I. (1989). Existential psychotherapy. Current Psychotherapies,

pp.363-404.

Rychlak, J. (1981). Introduction to Personality

and Psychotherapy: Second Edition. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Yalom, I. (2002). The Gift of Therapy: An open

letter to a new generation of therapists

and their patients. New York: Harper

Collins.

Yalom, I. (1981). Existential psychotherapy.

New York: Basic Books.

www.ExistentialPsychology.org

You might also like

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Poems That Shoot Guns: Emin Em, Spittin' Bullets, and The Meta-RapDocument20 pagesPoems That Shoot Guns: Emin Em, Spittin' Bullets, and The Meta-RapInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- I Always Felt Like I Was On Pretty Good Terms With The Virgin Mary, Even Though I Didn'T Get Pregnant in High SchoolDocument9 pagesI Always Felt Like I Was On Pretty Good Terms With The Virgin Mary, Even Though I Didn'T Get Pregnant in High SchoolInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Short Fiction/Essays: Paradise HadDocument4 pagesShort Fiction/Essays: Paradise HadInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- A Cinderella Story: Michelle SeatonDocument2 pagesA Cinderella Story: Michelle SeatonInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Poorirma: Marie Sheppard WilliamsDocument11 pagesPoorirma: Marie Sheppard WilliamsInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- 352 570 1 PB PDFDocument19 pages352 570 1 PB PDFInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Short Fiction/Essays: Lost InnocenceDocument4 pagesShort Fiction/Essays: Lost InnocenceInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Handprints On The Wall: Cyril DabydeenDocument3 pagesHandprints On The Wall: Cyril DabydeenInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- 292 506 1 PB PDFDocument22 pages292 506 1 PB PDFInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- 1930 8714 1 PBDocument3 pages1930 8714 1 PBInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Morphine and Bullets: Ola AbdalkaforDocument4 pagesMorphine and Bullets: Ola AbdalkaforInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Performing African American Womanhood: Hazel Scott and The Politics of Image in WWII AmericaDocument16 pagesPerforming African American Womanhood: Hazel Scott and The Politics of Image in WWII AmericaInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Dennis Walder 204 Pages, 2012, $44.95 USD (Hardcover) New York and London, RoutledgeDocument4 pagesDennis Walder 204 Pages, 2012, $44.95 USD (Hardcover) New York and London, RoutledgeInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- "I Don't Think I Am Addressing The Empire": An Interview With Mohammed HanifDocument11 pages"I Don't Think I Am Addressing The Empire": An Interview With Mohammed HanifInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Syrine Hout 224 Pages, 2012, $104 USD/ 65 (Hardcover) Edinburgh, Edinburgh University PressDocument4 pagesSyrine Hout 224 Pages, 2012, $104 USD/ 65 (Hardcover) Edinburgh, Edinburgh University PressInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Gaston Miron: Encountering Trauma in The Linguistic (De) Colonization of QuébecDocument17 pagesGaston Miron: Encountering Trauma in The Linguistic (De) Colonization of QuébecInternational Journal of Transpersonal StudiesNo ratings yet

- Free Higher Education Application Form 1st Semester, SY 2021-2022Document1 pageFree Higher Education Application Form 1st Semester, SY 2021-2022Wheng NaragNo ratings yet

- Schematic Diagram For Pharmaceutical Water System 1652323261Document1 pageSchematic Diagram For Pharmaceutical Water System 1652323261Ankit SinghNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- TCJ Series: TCJ Series - Standard and Low Profile - J-LeadDocument14 pagesTCJ Series: TCJ Series - Standard and Low Profile - J-LeadgpremkiranNo ratings yet

- Industries Visited in Pune & LonavalaDocument13 pagesIndustries Visited in Pune & LonavalaRohan R Tamhane100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Calao Deliquente Diadi River SystemDocument15 pagesCalao Deliquente Diadi River SystemJason MalamugNo ratings yet

- Cis MSCMDocument15 pagesCis MSCMOliver DimailigNo ratings yet

- Total Elbow Arthroplasty and RehabilitationDocument5 pagesTotal Elbow Arthroplasty and RehabilitationMarina ENo ratings yet

- 2015 12 17 - Parenting in America - FINALDocument105 pages2015 12 17 - Parenting in America - FINALKeaneNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Me N Mine Science X Ist TermDocument101 pagesMe N Mine Science X Ist Termneelanshujain68% (19)

- Coarse DispersionsDocument35 pagesCoarse Dispersionsraju narayana padala0% (1)

- Figure 1: Basic Design of Fluidized-Bed ReactorDocument3 pagesFigure 1: Basic Design of Fluidized-Bed ReactorElany Whishaw0% (1)

- Rigging: GuideDocument244 pagesRigging: Guideyusry72100% (11)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- DeMeo HERETIC'S NOTEBOOK: Emotions, Protocells, Ether-Drift and Cosmic Life Energy: With New Research Supporting Wilhelm ReichDocument6 pagesDeMeo HERETIC'S NOTEBOOK: Emotions, Protocells, Ether-Drift and Cosmic Life Energy: With New Research Supporting Wilhelm ReichOrgone Biophysical Research Lab50% (2)

- Week5 6 2Document2 pagesWeek5 6 2SAMANIEGO BERMEO DAVID SEBASTIANNo ratings yet

- Kingdom of AnimaliaDocument6 pagesKingdom of AnimaliaBen ZerepNo ratings yet

- Of Periodontal & Peri-Implant Diseases: ClassificationDocument24 pagesOf Periodontal & Peri-Implant Diseases: ClassificationruchaNo ratings yet

- Schindler 3100: Cost-Effective MRL Traction Elevator For Two-And Three-Story BuildingsDocument20 pagesSchindler 3100: Cost-Effective MRL Traction Elevator For Two-And Three-Story BuildingsHakim BgNo ratings yet

- OM Hospital NEFTDocument1 pageOM Hospital NEFTMahendra DahiyaNo ratings yet

- Sol. Mock Test CBSE BiologyDocument3 pagesSol. Mock Test CBSE BiologysbarathiNo ratings yet

- PulpectomyDocument3 pagesPulpectomyWafa Nabilah Kamal100% (1)

- Astm d2729Document2 pagesAstm d2729Shan AdriasNo ratings yet

- Building and Environment: Nabeel Ahmed Khan, Bishwajit BhattacharjeeDocument19 pagesBuilding and Environment: Nabeel Ahmed Khan, Bishwajit Bhattacharjeemercyella prasetyaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- List of Government Circuit Bungalow Nuwara EliyaDocument4 pagesList of Government Circuit Bungalow Nuwara EliyaAsitha Kulasekera78% (9)

- Vaccination Schedule in Dogs and CatsDocument3 pagesVaccination Schedule in Dogs and CatsAKASH ANANDNo ratings yet

- Measurement of Bioreactor K ADocument18 pagesMeasurement of Bioreactor K AAtif MehfoozNo ratings yet

- Index Medicus PDFDocument284 pagesIndex Medicus PDFVania Sitorus100% (1)

- Boeco BM-800 - User ManualDocument21 pagesBoeco BM-800 - User ManualJuan Carlos CrespoNo ratings yet

- An Energy Saving Guide For Plastic Injection Molding MachinesDocument16 pagesAn Energy Saving Guide For Plastic Injection Molding MachinesStefania LadinoNo ratings yet

- 8 Categories of Lipids: FunctionsDocument3 pages8 Categories of Lipids: FunctionsCaryl Alvarado SilangNo ratings yet

- Iso 9227Document13 pagesIso 9227Raj Kumar100% (6)

- The Inside Game: Bad Calls, Strange Moves, and What Baseball Behavior Teaches Us About OurselvesFrom EverandThe Inside Game: Bad Calls, Strange Moves, and What Baseball Behavior Teaches Us About OurselvesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

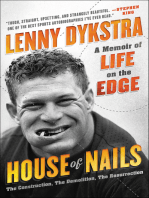

- House of Nails: A Memoir of Life on the EdgeFrom EverandHouse of Nails: A Memoir of Life on the EdgeRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)