Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Michael Newman 'Fiona Tan: The Changeling' (2009)

Uploaded by

mnewman14672Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Michael Newman 'Fiona Tan: The Changeling' (2009)

Uploaded by

mnewman14672Copyright:

Available Formats

V

THE CHANGELING

THE OTHER FACE T0 FACE

iviici-iAELNEwMAN

Every portrait can be conceived as a se/f-portrait of the artist

and of the viewer, as well as a portrait of the ostensible subject

whose always present image substitutes for the mirror-image.

And every self-portrait could equally be conceived as a portrait ofthe other, of the as another, to paraphrase Rimbaud!

In addition, as the philosopher Jacques Derrida points out

I

Memoirs of the Blind, in looking at a self-portrait that has

been painted or drawn using a mirror, the viewer takes the

place of the mirror, substituting his or her eyes for the eyes

of the artist, who is thus retroactively blinded?

in

In

Fiona Tan's installation, The Change/ing (2006).

single

image of a Japanese schoolgirl is placed opposite a screen

on which over 200 images of different girls from the same

pre-World War ll high school yearbook are shown in sequence.

the girls were looking directly into the camera when the

photographs were taken, so we have the impression that they

are looking back at us, but from long ago, their frozen pastpresent interrupting our current time. The image sequence

limits how long we can examine each of the many faces before

All

passes away. The single image feels more

something

held and preserved, overcoming time yet imbued with the very

sense of loss for which this preservation partly compensates.

Placing the one face to face with the many sets up a play

of sameness and difference. If we look at how this works

across two axes the distinction between difference and otherness becomes evident. The first involves the relationship of

the images to each other and the second depends on the way

the viewer projects presuppositions onto the image. In this

first way, independently of the viewer, the photographs of the

girls, like the girls themselves, are both similar to and different from each other. They are members of a generation, a race

and, judging by the uniform, an institution, but at the same

time each face, with its unique qualities and physiognomy,

stands out amongst all the others.

But the relational differences between each of the members of this archive of images is not the same as the relational

difference experienced by the viewer who stands outside and

looks, nor the projected possibility of being seen that existed

for the subject when photographed. The axis of sameness and

difference is intersected by that of self and other. The photograph becomes a mirror image-all the more so through its

extension in durational time as video-while the subject of the

it

THE CHANGELING,

like

zoo6 (INSTALLATION vnzw)

NEWMAN

photograph becomes the other of the viewer: the viewer confronts his or her other as image, and an image with a duration

like a mirror image. The question then arises: what is the

relation of this kind of otherness to difference? Put bluntly, is

the other person other because they are different, where this

difference is a matter of identity that is perceivable through

physical qualities and other markers such as racial identity.

gender, membership of a group indicated by clothing, and

so on? But how can these qualities relate to otherness in the

sense of singularity when they are shared with others? The

uniqueness of the other as other cannot be a matter of qualities

and identifications, or even concatenations of them. The singularity ofthe other is beyond, even transcends, these things?

The fascination of a portrait photograph is that the subject

of the photograph overflows the contingency and indifference

of its qualities. The photograph records whatever is physically

there in front of the camera. ln the case of these girls. the format is a standard head and shoulders. The uniformity draws

attention to the way the institution represses difference and

to the conformity of the photographic archive with processes

of social control. Yet, perhaps because we know that it was a

person in her singularity who composed herself and posed

in front of the camera, the image seems to exceed its limits

(and is in this respect like an icon). All the girls are facing

forward, but what, exactly are they facing? The camera? The

future viewer? Themselves reflected in the lens? We are confronted simultaneously with the image of a Japanese schoolliving

the 1930s-the photograph as the that-has-been" of

the moment in which it was taken-but also with an other who

seems to regard us. This other looks at the viewer in the present of an encounter rather than the past of an image, and concerns that viewer in the French sense of regarder as both look

and concern (ga me regarde, literally "it looks at me," means "it

girl of

concerns me," in the sense that the image addresses me

uniquely and calls for me to respond).

While the photograph as a registration of light records a

past moment, the experience of being looked at by the subject of the photograph takes place in the present ofthe viewer,

and the concern to which it gives rise projects a future of

response. All these temporal moments enter into the voiceover that accompanies the images. The photograph represents

both a memory of the past and an anticipation of the future.

The woman's voice, together with the digital presentation of

the image on a monitor, places it in a temporal flow, which

mitigates the status of an archival relic it would otherwise

assume: the image is in the time that carries the viewer on

towards a future that will inevitably involve aging and death.

um cuANr;m,1Nr:, zoo6 (sT1i,i.s)

THE CHANGELING

great success, as people did not want to

be disabused of their illusions by seeing how others saw them.

This reveals something of the truth of the portrait-and the

self-portrait-that the self anticipates how it will be seen by

others. The later Provenance (2008)-six films of people in

some way connected to Tan, shown in their familiar environments and presented on monitors hanging on the wall-was

photograph itself will not change. The voice speaks

from positions that offer the viewer identifications with generations of women-grandmother, mother, daughter-among

who, in more than one place, is the artist. ln addition, each

of the voices of the actors employed to speak in installations

of the work in different linguistic communities has its own

grain" which gives the words a particular texture and speci-

invention was not

ficity, their "body_"5

response to Dutch seventeenth century portrait

painting? The black and white moving images (the subjects

are seen both in fixed shots and in slow tracking shots) have

in principle less physical presence than oil paintings, but

greater temporal presence.

The philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy suggests that the painted

portrait projects itself ahead of itself, like the wake before

the prow ofa ship.1 This also implies a protean quality to the

portrait, which involves less a fixing of the subject in representation than it does an exposure of the subject to the world.

ln mythology and folk tale a Changeling is the offspring of a

fairy or troll who is substituted for a human child: this implies

two things, that someone like us, the same, has been replaced

by an alien other, and that this has occurred through an event

or process of substitution. The act of making a photograph is a

fixing of the subject, both in the registration that takes place

when the button of the camera is pressed, and again when a

print is made. Yet through the temporalization of the still

photographic image, by using a video camera to record an

archival photograph, Tan transforms an object into a process.

ln a number of works Tan places the still and moving image in an

even

if the

Photographs often, and almost inevitably, become unmoored from the proper names of their subjects. Most of us

will have had the experience of looking at family photographs

in albums where names can no longer be put to faces. The

proper name is the linguistic sign for singularity, even if the

subject is only rarely the bearer of her proper name (or, in the

case of a photographic subject, rarely labelled). Without her

name, the girl becomes a subject for identification through a

personal pronoun: an I, a you or a she.6 These are positions

with which absolutely anyone may identify, whether or not race.

gender, or community are shared with the subject of the photograph; they are entirely abstract and universal, and may be

occupied by anyone who knows the language. ln the published

version of the voice-over, attributions of the words to She"

and "I" frame those to "Grandmother" and "Mother" The specification is provided by a narrative fiction into which the viewer

may slide, in this case the implied story of the relationships

between grandmother, mother and daughter. In the circum-

stances of diaspora (Tan was born in Indonesia of a Chinese

father and an Australian-Scottish mother, brought up in Australia and lives in the Netherlands) family becomes an important source of identity. Family is also a particularly important

value in Chinese culture, and in her essay film for television,

May You Live in Interesting Times (1997), Tan went in search of

her Chinese roots. She interviewed the members of her family

now scattered around the world, ending up in the village in China

from which the Tan family originated. I started this journey in

search of mirrors," she says, but realizes that she will never

feel entirely part of her family, nor can she be at home in this

village: My self-definition seems an impossibility, an identity

defined only by what it is not."

Tan named an exhibition of her work in which The Changeling

was shown, Mirror Maker, implyingthat what she is doing in her

work is making devices or mises-en-scene that produce reflections, in the metaphoric as well as literal sense? She took

the title from a story by Primo Levi, in which the mirror maker

fabricates not only flat and distorting mirrors, but also invents

a

mirror that, when stuck to the forehead of someone else,

reflect back to you how they see you. ln Levi's story this

will

explicitly

interdependent relationship. ln Countenance (2002) Tan made

video images of people standing still, Berliners who were classified in the same way as those in August Sander's Menschen

des 20. Jahrhunderts. (She did this as much to show the

impossibility of that project as to follow it.) ln Correction (2004)

Tan used the same procedure with prisoners and guards from

four US prisons. In The Changeling, by giving duration to the

photograph through video, Tan unfixes the photograph's fixity

without abolishing it. Although we know that we are looking at

a photograph, what we are seeing has its own time span.

which is reinforced by the duration of the accompanying

voice-over. In a sense, Tan allows the subjects of the portraits

some space and time to present themselves. In The Changeling

it is as if Tan is restoring this capacity to people who have been

frozen in the image.

The fixing itself becomes a moment in a narrative duration.

but this moment is given more meaning by the voice-over

which cites Daphne and Niobe, two female figures from Ovid's

Metamorphoses, whose stories are described as ... bearing

THE CHANGELING,

2006 (INSTALLATION visw)

NEWMAN

the weight of too much sadness." Daphne, who is fleeing the

desire of Apollo, is turned into a Laurel tree by her father, the

river Peneus. Niobe, whose children are killed because of her

prideful offence to the goddess Latona. turns to stone in grief.

Thus, the freezing of the woman's self in the photograph, juxtaposed to Ovid's stories, comes to seem no mere mechanical

act but a response to the threat of rape and overwhelming

pain. However, this consideration ofthe photograph as a metamorphosis requires that we see it within a process of change

and generation over time.

As with some of her other pieces, Tan`s making of The

Changeling is an act of appropriation, in this case of images

which, in the album or place where she found them, had a context. The persons inthe original photographs would have been

named and so would the school and community to which they

belonged. Although still generally identifiable as coming from

a particular generation, time period and country, even perhaps ofa social class, in Tan's installation the subjects of the

photographs are disconnected from their original, very particular, context. The unease of the viewer at this appropriation is part of the experience of the work, as it was with

Tan's earlier borrowings from the anthropological archive; the

1999 works Facing Forward and Tuareg, for example. ln those

works the colonizing photograph is disrupted by a confron-

tation with or experience of the other in the present time of

viewing, and despite geographical and temporal remoteness,

a spark of unmediated connection is created between viewer

and viewed.

If The Changeling takes over an archive of portraits of others, the voice-over offers the possibility that these images

might constitute a kind of self-portrait. What does the artist

do when she makes a self-portrait? She looks at herself in the

mirror, but what is she looking for? Her self? What, then, is

the relation of self to appearance? And what if, in place ofthe

mirror, a photograph appears? ln answer to the question.

appears in her place. What does the subportrait

photograph is taken of her. whether by

ject do when

herself, or another? She composes herself, presents herself

Who am l?" another

a

as she wants to appear, projects herself towards those who

will see her picture in the future, envisaging herself in their

eyes. So when, at the end, the voice-over says, A self-portrait

in search, yet again, of self," this could refer both to the artist.

Fiona Tan. searching for herself in the pictures of the Japan-

ese girls, of whom we know nothing, and also to those girls.

composing themselves for the portraits which will be presented to us, their unknown future viewers.

THE CHANGELING,

zoo6 (INSTALLATION views)

10

11

Letter to Paul Demeny. Charleville, May 15, 1871.

Jacques Derrida, Memoirs of the B/ind: The Self-Portrait and Other

Ruins (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993). 60-63.

My distinction between otherness based on identity and otherness

based on the absolute singularity of the other draws on the philosophy

of Emmanuel Lvinas. See his discussion of the face of the other in

Emmanuel Lvinas. Tota/ity and Infinity; an Essay on Exteriority (Pittsburgh: Duquesne University Press, 1969) and of the traumatic character

of the unmediated relation with the other in Emmanuel Lvinas. Otherwise Than Being: on Beyond Essence (The Hague: M. Nijhoff. 1981).

Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York:

Hill and Wang.1981).77

Roland Barthes, "The Grain of the Voice" in The Responsibility of Forms.

trans. Richard Howard (Berkeley and LA: The University of California

Press, 1991), 267-77

In linguistics these personal pronouns, together with words like this

and "that," which take on their meaning according to the context of use.

are called shifters." See Roman Jakobson, "Shifter, verbal categories.

and the Russian verb" in Roman Jakobson, Linda R. Waugh and Monique

Monville-Burston eds. On Language (Cambridge. MA: Harvard University

Press. 1990). 115-133.

See the catalogue Fiona Tan Mirror Maker (Linz: Oberosterreichische

Landesmuseen; and Heidelberg: Kehrer Verlag, 2006).

Primo Levi, The Mirror Maker, trans. Raymond Rosenthal (London.

Abacus, 1997), 55-60.

See the catalogue Provenance (Amsterdam: Rijksmuseum, 2008) with

an exquisite essay by Fiona Tan.

Jean-Luc Nancy, Le Regard du portrait (Paris: Galil, 2000), 48: Nancy

also plays on the notion of "regard" on 71-83.

For a discussion of The Change/ing in relation to the archive, see Philip

Monk, Disassembling the Archive: Fiona Tan (Toronto: Art Gallery of

York University, 2007).

I2

RISE AND FALL

FIONA TAN

Published in conjunction with the exhibition Fiona Tan: Rise and Fall

organized by the Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver. Canada and the

Aargauer Kunsthaus. Aarau, Switzerland.

EXHIBITION ITINERARY

Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau. Switzerland

January 30 - April 18, 2010

The Vancouver Art Gallery is a not-for-profit organization supported by its

members: individual donors: corporate funders: foundations: the City of

Vancouver: the Province of British Columbia through the BC Arts Council

and Gaming Revenues: the Canada Council for the Arts; and the Government of Canada through the Department of Canadian Heritage.

Vancouver Art Gallery, Vancouver, Canada

May 9 - September 6. 2010

Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, USA

September 18, 2010 - January 9, 2011

Galerie de l`UQAM Montral. Canada

February 25 - April 5, 2011

..|..... |.......:

The catalogue and exhibition were realized with

the financial support of the Mondriaan Foundation.

Amsterdam-

Vancouver

Artgallery

750 Hornby Street.

Vancouver, BC, Canada V62 2H7

1 (604) 662 4700

www.vanartgallery.bc.ca

Tel:

Publication coordination: Stephanie Rebick, Vancouver Art Gallery

Editing: Judith Penner

Design: Studio: Blackwell

Digital Image Preparation: Trevor Mills and Rachel Topham.

Vancouver Art Gallery

Printed in Canada by Friesens

Publication 2009 Vancouver Art Gallery

Artwork 2009 Fiona Tan

Individual texts 2009 the authors

rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored

system or transmitted, in any form or by any means. without

the prior written consent of the publisher or a license from The Canadian

Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For

a copyright license, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to

1-800-893-5777

All

in

*Aargauer Kunsthaus

Aargauer Kunsthaus

Postfach

CH-5001Aarau

T +41 (O) 62 835 23 30

F+4l (0) 62 835 23 29

kunsthaus@ag.ch

www.aargauerkunsthaus.ch

a retrieval

All artworks by Fiona Tan are reproduced courtesy of the artist

and Frith Street Gallery, London.

IMAGE CREDITS

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Rise and Fall Fiona Tan / edited by Bruce Grenville with

contributions from Okwui Enwezor [et al.].

Co-published by: Aargauer Kunsthaus.

Catalogue of an exhibition held at the Aargauer Kunsthaus, Aarau.

Switzerland. Jan-30-Apr. 18,2010 and at the Vancouver Art Gallery.

Vancouver, B.C., May 9-Sept. 6, 2010 and then travelling to other venues.

ISBN: 978-1-895442-79-3

Fiona,1966- --Exhibitions. l.Grenville, Bruce ll. Enwezor,0kwui

1966- IV. Aargauer Kunsthaus V. Vancouver Art Gallery

N6953.T36A4 2010

709.2

C2009-906824-9

1,

Tan,

Ill.

Tan. Fiona,

pp. 22-24, 38-39, 81 installation view of Fiona Tan, Disorient, Dutch Pavilion.

Venice Biennale, June 7-November 22, 2009. photo: Per Kristiansen.

Stockholm; p. 42 photo: Rachel Topham, Vancouver Art Gallery; pp. 46,

52-53 installation view of Provenance, Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. August

27-0ctober19. 2008. photo: Staeske Rebers. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam;

pp. 54. 64-65 installation view of Island, MAP Stockholm. October 3October 26, 2008, photo: Per Kristiansen. Stockholm; pp. 66, 76-77

installation view of Mirror Maker, Kunsthallen Brandts. Odense, February

25-May 21. 2006, photo: Torben Eskerod. Kunsthallen Brandts. Odense:

pp. 72, 75, 85 installation view of Time and Again, Lunds Konsthall,

November 24. 2007-January 22 2008. photo: Terje Ostling, Lunds

Konsthall: pp.92-93 Installation view of A Lapse of Memory, Chapelle

de Genteil Centre d'Art Contemporain - Le Carr Scene Nationale,

Chateau-Gontier, April 5-June 1, 2008. Photo: Marc Domage/ F iona Tan

You might also like

- Notes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Document16 pagesNotes On The Demise and Persistence of Judgment (William Wood)Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Position and Program. Helio OiticicaDocument3 pagesPosition and Program. Helio OiticicasenseyitoNo ratings yet

- Dezeuze - Hélio Oiticica's ParangolésDocument15 pagesDezeuze - Hélio Oiticica's ParangolésMartha SchwendenerNo ratings yet

- BirnbaumDocument9 pagesBirnbaumJamieNo ratings yet

- Intermedia CatalogDocument65 pagesIntermedia CatalogJosé Antonio LuceroNo ratings yet

- Erasure in Art - Destructio..Document12 pagesErasure in Art - Destructio..lecometNo ratings yet

- Paolini's Studies On PerspectiveDocument7 pagesPaolini's Studies On Perspectivestefi idlabNo ratings yet

- The Pictorial Jeff WallDocument12 pagesThe Pictorial Jeff WallinsulsusNo ratings yet

- Bil Viola - Shifting EncountersDocument15 pagesBil Viola - Shifting EncountersManuelNo ratings yet

- E. Kosuth, Joseph and Siegelaub, Seth - Reply To Benjamin Buchloh On Conceptual ArtDocument7 pagesE. Kosuth, Joseph and Siegelaub, Seth - Reply To Benjamin Buchloh On Conceptual ArtDavid LópezNo ratings yet

- Pierre Huyghe. Les Grands: Ensembles, 2001. VistavisionDocument24 pagesPierre Huyghe. Les Grands: Ensembles, 2001. Vistavisiontemporarysite_orgNo ratings yet

- How To Do Things With Art. What Performativity Means in Art Artigo 3Document197 pagesHow To Do Things With Art. What Performativity Means in Art Artigo 3Cinara Barbosa100% (1)

- Towards A HyperphotographyDocument14 pagesTowards A HyperphotographyroyalnasonNo ratings yet

- Buchloh On Dada Texte Zur KunstDocument5 pagesBuchloh On Dada Texte Zur Kunstspring_into_dadaNo ratings yet

- Pure Immanence Intro - John RajchmanDocument9 pagesPure Immanence Intro - John RajchmanMitch MargolisNo ratings yet

- Afterimage 22 (January 1995)Document39 pagesAfterimage 22 (January 1995)Lei RmzNo ratings yet

- Christian BoltanskiDocument17 pagesChristian BoltanskichnnnnaNo ratings yet

- Truth of PhotoDocument117 pagesTruth of PhotoLeon100% (1)

- A Cinema in The Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins: ErikabalsomDocument17 pagesA Cinema in The Gallery, A Cinema in Ruins: ErikabalsomD. E.No ratings yet

- Allan Sekula - War Without BodiesDocument6 pagesAllan Sekula - War Without BodiesjuguerrNo ratings yet

- Michele BertolinoDocument12 pagesMichele BertolinoDyah AmuktiNo ratings yet

- Pensamiento GeometricoDocument28 pagesPensamiento GeometricomemfilmatNo ratings yet

- Rudolf Laban S Dance Film Projects in NeDocument16 pagesRudolf Laban S Dance Film Projects in NeSilvina DunaNo ratings yet

- Photography - HistoryDocument27 pagesPhotography - HistoryMiguelVinci100% (1)

- Piero Manzoni 1Document12 pagesPiero Manzoni 1Karina Alvarado MattesonNo ratings yet

- Whats The Point of An Index, Tom GunningDocument12 pagesWhats The Point of An Index, Tom GunningMaria Da Luz CorreiaNo ratings yet

- Sarah James Cold War PhotographyDocument23 pagesSarah James Cold War PhotographycjlassNo ratings yet

- Tom Gunning - What's The Point of An IndexDocument12 pagesTom Gunning - What's The Point of An IndexJu Simoes100% (1)

- Indirect Answers: Douglas Crimp On Louise Lawler'S Why Pictures Now, 1981Document4 pagesIndirect Answers: Douglas Crimp On Louise Lawler'S Why Pictures Now, 1981AleksandraNo ratings yet

- Le Feuvre Camila SposatiDocument8 pagesLe Feuvre Camila SposatikatburnerNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster Which Red Is The Real Red - LRB 2 December 2021Document12 pagesHal Foster Which Red Is The Real Red - LRB 2 December 2021Leonardo NonesNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument27 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University PressTabarek HashimNo ratings yet

- 2009 HendersonDocument31 pages2009 HendersonstijnohlNo ratings yet

- Ruscha (About) WORDSDocument5 pagesRuscha (About) WORDSarrgggNo ratings yet

- RIEGL, Aloïs. 1995. Excerpts From The Dutch Group PortraitDocument34 pagesRIEGL, Aloïs. 1995. Excerpts From The Dutch Group PortraitRennzo Rojas RupayNo ratings yet

- Mark Godfrey Simon Starlings Regenerated SculptureDocument5 pagesMark Godfrey Simon Starlings Regenerated SculptureMahan JavadiNo ratings yet

- Branden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFDocument33 pagesBranden-W-Joseph-RAUSCHENBERG White-on-White PDFjpperNo ratings yet

- Foster - Hal - Primitve Unconscious of Modern ArtDocument27 pagesFoster - Hal - Primitve Unconscious of Modern ArtEdsonCosta87No ratings yet

- Bois Krauss Intros3 4 ArtSince1900Document17 pagesBois Krauss Intros3 4 ArtSince1900Elkcip PickleNo ratings yet

- Semiotics and Western Painting: An Economy of SignsDocument4 pagesSemiotics and Western Painting: An Economy of SignsKavya KashyapNo ratings yet

- Kessler Dispositif Notes11-2007Document19 pagesKessler Dispositif Notes11-2007Janna HouwenNo ratings yet

- Artbasel 2006Document55 pagesArtbasel 2006mornadiaNo ratings yet

- Situationist ManifestoDocument3 pagesSituationist ManifestoRobert E. HowardNo ratings yet

- William Kentridge and Carolyn ChristovDocument2 pagesWilliam Kentridge and Carolyn ChristovToni Simó100% (1)

- Bright ShoppingDocument19 pagesBright ShoppingAndré PitolNo ratings yet

- Henry Flynt The Art Connection My Endeavors Intersections With Art 1Document14 pagesHenry Flynt The Art Connection My Endeavors Intersections With Art 1Emiliano SbarNo ratings yet

- Flusser and BazinDocument11 pagesFlusser and BazinAlberto Carrillo CanánNo ratings yet

- Photography and Cinematic Surface: EssayDocument5 pagesPhotography and Cinematic Surface: EssayVinit GuptaNo ratings yet

- The Association Kunsthalle Marcel Duchamp, Cully, SwitzerlandDocument3 pagesThe Association Kunsthalle Marcel Duchamp, Cully, Switzerlandapi-25895744No ratings yet

- Abigail Solomon-Godeau - The Azoulay AccordsDocument4 pagesAbigail Solomon-Godeau - The Azoulay Accordscowley75No ratings yet

- Physicality of Picturing... Richard ShiffDocument18 pagesPhysicality of Picturing... Richard Shiffro77manaNo ratings yet

- Benjamin Optical Unconscious Conty PDFDocument15 pagesBenjamin Optical Unconscious Conty PDFDana KiosaNo ratings yet

- Bourriaud PostproductionDocument47 pagesBourriaud Postproductionescurridizo20No ratings yet

- Denson Aesthetics and Phenomenology Syllabus 2019Document6 pagesDenson Aesthetics and Phenomenology Syllabus 2019medieninitiativeNo ratings yet

- Hal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Document4 pagesHal Foster Reviews Ways of Curating' by Hans Ulrich Obrist and Curationism' by David Balzer LRB 4 June 2015Azzad Diah Ahmad ZabidiNo ratings yet

- Claire Bishop IntroductionDocument2 pagesClaire Bishop IntroductionAlessandroValerioZamoraNo ratings yet

- Invisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You) : The New InquiryDocument12 pagesInvisible Images (Your Pictures Are Looking at You) : The New InquiryDavidNo ratings yet

- Camera NotesDocument1,662 pagesCamera NotesAndrei PoseaNo ratings yet

- Image ModelerDocument23 pagesImage ModelerLaboratório Patrimônio e Desenvolvimento0% (1)

- Wedding Photography ContractDocument3 pagesWedding Photography ContractAdewale MomoreoluwaNo ratings yet

- Teju Cole Object LessonDocument5 pagesTeju Cole Object LessonAndrew Redmund-Barry KucbelNo ratings yet

- The Inspired Eye - Vol 3Document32 pagesThe Inspired Eye - Vol 3Patrick100% (1)

- Đề chọn đt hsg hhtDocument30 pagesĐề chọn đt hsg hhtNguyễn Quốc HuyNo ratings yet

- AppointmentconfirmationDocument3 pagesAppointmentconfirmationInthiyaz KhanNo ratings yet

- Michael Newman 'Fiona Tan: The Changeling' (2009)Document6 pagesMichael Newman 'Fiona Tan: The Changeling' (2009)mnewman14672No ratings yet

- Gullickson's Glen by Daniel SeurerDocument15 pagesGullickson's Glen by Daniel SeurerasdaccNo ratings yet

- Shaking Hands With Other Peoples PainDocument19 pagesShaking Hands With Other Peoples PainGimonjoNo ratings yet

- Lets Shoot Tomorrow Gk68Document108 pagesLets Shoot Tomorrow Gk68Leóstenis Gonçalves de Almeida100% (2)

- How To Make Your Own Calendars & Start A Calendar Business!Document14 pagesHow To Make Your Own Calendars & Start A Calendar Business!Martin Hurley100% (1)

- Odyssey Marine Exploration, Inc. v. The Unidentified Shipwrecked Vessel - Document No. 88Document7 pagesOdyssey Marine Exploration, Inc. v. The Unidentified Shipwrecked Vessel - Document No. 88Justia.comNo ratings yet

- Mastering Digital PhotographyDocument370 pagesMastering Digital PhotographyBethNo ratings yet

- The Museums of The Future The Future Is NOWDocument10 pagesThe Museums of The Future The Future Is NOWDarya PauNo ratings yet

- Exhibition As Archive Beaumont Newhall Photography 1839 1937 and The Museum of Modern ArtDocument9 pagesExhibition As Archive Beaumont Newhall Photography 1839 1937 and The Museum of Modern ArtDiego Fernando GuerraNo ratings yet

- B2 English SampleDocument16 pagesB2 English SampleБахрамов МардонNo ratings yet

- Art Elements in Media-Based Arts in The Philippines: Lesson 1Document31 pagesArt Elements in Media-Based Arts in The Philippines: Lesson 1kathrine cadalso100% (1)

- STP 31-18F34 MOS18F Special Forces AO and Intelligence Sergeant 1994Document318 pagesSTP 31-18F34 MOS18F Special Forces AO and Intelligence Sergeant 1994Chris Whitehead100% (2)

- Nenavadna-Slovenija - Photo Competition Switzerland 2011Document1 pageNenavadna-Slovenija - Photo Competition Switzerland 2011Institute for Slovenian Studies of Victoria Inc.No ratings yet

- Photo Lithography PDFDocument10 pagesPhoto Lithography PDFBrahmanand SinghNo ratings yet

- 3.lecture - 2 Type of Areal PhotgraphDocument34 pages3.lecture - 2 Type of Areal PhotgraphFen Ta HunNo ratings yet

- Instructions Ver 4.0 - Final1Document58 pagesInstructions Ver 4.0 - Final1shashisbs09No ratings yet

- Media Based ArtDocument5 pagesMedia Based ArtCHAPEL JUN PACIENTENo ratings yet

- 3530 Nellikuppam Clarifier SpecDocument62 pages3530 Nellikuppam Clarifier Specgopalakrishnannrm1202100% (1)

- Digital Photography Sem. 1: Textbook AssignmentsDocument7 pagesDigital Photography Sem. 1: Textbook Assignmentsmariahna whitfieldNo ratings yet

- Photographic TechnologyDocument19 pagesPhotographic Technologyapi-350378778No ratings yet

- Outside in and Upside Down: The Art of Abelardo Morell: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleDocument15 pagesOutside in and Upside Down: The Art of Abelardo Morell: Click To Edit Master Subtitle StyleAllissa SmithNo ratings yet

- USA V CARICO - Unsealed AffidavitDocument10 pagesUSA V CARICO - Unsealed AffidavitFile 411No ratings yet

- Photography and CinemaDocument161 pagesPhotography and Cinemaapollodor100% (6)

- Art Models AnaIv309: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models AnaIv309: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Watercolor in Nature: Paint Woodland Wildlife and Botanicals with 20 Beginner-Friendly ProjectsFrom EverandWatercolor in Nature: Paint Woodland Wildlife and Botanicals with 20 Beginner-Friendly ProjectsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Art Models Sam074: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models Sam074: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Creative Abstract Watercolor: The beginner's guide to expressive and imaginative paintingFrom EverandCreative Abstract Watercolor: The beginner's guide to expressive and imaginative paintingRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Drawing and Sketching Portraits: How to Draw Realistic Faces for BeginnersFrom EverandDrawing and Sketching Portraits: How to Draw Realistic Faces for BeginnersRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (5)

- Art Models AnaRebecca002: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models AnaRebecca002: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Sketch-A-Day Drawing Challenge 2020: 365 pages of Drawing Prompts to inspire Artists, and Incite the imaginationFrom EverandSketch-A-Day Drawing Challenge 2020: 365 pages of Drawing Prompts to inspire Artists, and Incite the imaginationRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Swatch This, 3000+ Color Palettes for Success: Perfect for Artists, Designers, MakersFrom EverandSwatch This, 3000+ Color Palettes for Success: Perfect for Artists, Designers, MakersRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Fundamentals of Character Design: How to Create Engaging Characters for Illustration, Animation & Visual DevelopmentFrom EverandFundamentals of Character Design: How to Create Engaging Characters for Illustration, Animation & Visual Development3dtotal PublishingRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- How to Draw Anything Anytime: A Beginner's Guide to Cute and Easy Doodles (Over 1,000 Illustrations)From EverandHow to Draw Anything Anytime: A Beginner's Guide to Cute and Easy Doodles (Over 1,000 Illustrations)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (18)

- Art Models KatarinaK034: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models KatarinaK034: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Art Models Adrina032: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models Adrina032: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Art Models Becca425: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models Becca425: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Art Models AlyssaD010: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models AlyssaD010: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Anatomy for Fantasy Artists: An Essential Guide to Creating Action Figures & Fantastical FormsFrom EverandAnatomy for Fantasy Artists: An Essential Guide to Creating Action Figures & Fantastical FormsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (20)

- Art Models Jenni001: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models Jenni001: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Art Models SarahAnn031: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models SarahAnn031: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (4)

- The Complete Peanuts Family Album: The Ultimate Guide to Charles M. Schulz's Classic CharactersFrom EverandThe Complete Peanuts Family Album: The Ultimate Guide to Charles M. Schulz's Classic CharactersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Watercolor For The Soul: Simple painting projects for beginners, to calm, soothe and inspireFrom EverandWatercolor For The Soul: Simple painting projects for beginners, to calm, soothe and inspireRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (6)

- Art Magick: How to become an art witch and unlock your creative powerFrom EverandArt Magick: How to become an art witch and unlock your creative powerRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Sketch Your World: A Guide to Sketch Journaling (Over 500 illustrations!)From EverandSketch Your World: A Guide to Sketch Journaling (Over 500 illustrations!)No ratings yet

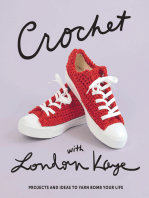

- Crochet with London Kaye: Projects and Ideas to Yarn Bomb Your LifeFrom EverandCrochet with London Kaye: Projects and Ideas to Yarn Bomb Your LifeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Art Models AnaIv533: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceFrom EverandArt Models AnaIv533: Figure Drawing Pose ReferenceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)