Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Service Labor and Symbolic Power - On Putting Bourdieu To Work

Uploaded by

Ana MaceoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Service Labor and Symbolic Power - On Putting Bourdieu To Work

Uploaded by

Ana MaceoCopyright:

Available Formats

Work http://wox.sagepub.

com/

and Occupations

Service Labor and Symbolic Power : On Putting Bourdieu to Work

Jeffrey J. Sallaz

Work and Occupations 2010 37: 295

DOI: 10.1177/0730888410373076

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://wox.sagepub.com/content/37/3/295

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Work and Occupations can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://wox.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://wox.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://wox.sagepub.com/content/37/3/295.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Aug 5, 2010

What is This?

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

Service Labor and

Symbolic Power: On

Putting Bourdieu to

Work

Work and Occupations

37(3) 295319

The Author(s) 2010

Reprints and permission: http://www.

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0730888410373076

http://wox.sagepub.com

Jeffrey J. Sallaz1

Abstract

The subfield that is the sociology of service labor continues to generate

vibrant internal dialogue. It was the authors original intent to push forward the

frontier of theory within this field, by performing an ethnography of service

work in a non-American context (that of post-apartheid South Africa). Once

in the field, however, he found himself moving backward as he was forced to

problematize basic assumptions concerning the very category of service. In

brief, the author discovered that managers in a competitive tourism industry

refused to label their employees interactive labor as service, whereas

workers themselves actively advocated for such a designation. To document

the interplay between material and symbolic politics of production, the author

turned to the work of Pierre Bourdieuespecially his theory of political

representation and the accompanying concept of nomination struggles.

Keywords

service work, Bourdieu, labor, South Africa

The most resolutely objectivist theory must take account of agents representation of the social world and . . . thereby to the very construction of this world,

via the labour of representation (in all senses of the term) that they continually

perform.

Bourdieu (1999a, p. 234)

University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA

Corresponding Author:

Jeffrey J. Sallaz, PO Box 210027, Tucson, AZ 85721, USA

Email: jsallaz@email.arizona.edu

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

296

Work and Occupations 37(3)

The service occupations today saturate our lifeworlds. They pour our lattes,

pluck our eyebrows, empty our bedpans. Nor can there can be any ambiguity

about the effect on sociological scholarship of this shift from an old, manufacturing-based economy to a new service society. The result has been a veritable paradigm shift in the sociology of work. Ethnographers intent on

documenting the organization of the labor process no longer trudge off to the

factory but, rather, to the local fast-food franchise. Scholars of labor movements increasingly focus their gaze not on the bureaucratic unions that long

dominated heavy industries and crafts but on the social movement unionism that holds hope for organizing low-wage service workers (Fantasia &

Voss, 2004; Lopez, 2004; Milkman, 2006). Also, the past two decades have

witnessed a proliferation of new theoretical frameworks for making sense of

the specificities of service work (MacDonald & Korczynski, 2009). Emotional labor, care work, and three-way interest alliance are all concepts of

recent origin, and all represent significant additions to the theoretical toolkit

passed down from classic studies of industrial sociology.

During the same period in which the sociology of work has been shaken

up the canon of sociological theory in America also has been. Parsonian

structural functionalism fell from favor during the late 1960s and 1970s, in

the face of both a radical resurgence of Marxist sociology and the emergence

of new theories centering the lived experience of women, minorities, and

other subalterns (Gouldner, 1970). The past two decades, meanwhile, has

witnessed a growing interest among American sociologists in the sociological research program pioneered by the late Pierre Bourdieu (Emirbayer &

Johnson, 2008). Although surprising in the sense that American sociology

has historically eschewed continental theory, Bourdieus theory represents a

powerful synthesis of the sociologies of Karl Marx (in its emphasis on power

and domination), Emile Durkheim (in its attention to the interplay between

cultural categories and social structure), and Max Weber (in its theorization

of legitimacy as an institutional process). Bourdieu is now one of the most

cited theorists in top American sociology journals (Sallaz & Zavisca, 2008).

Given these trends, it would be fair to say that the ground is ripe for dialogue

between these two emergent fields. In fact, sociologists of work have thoroughly explored at least one of Bourdieus key ideas: that of the habitus, the

embodied sens of reality through which social agents perceive and act on the

world. Desmond (2007), for instance, documented how the U.S. Forest Service

manages its labor supply by manipulating young mens rural-masucline habitus. Scholars of service and culture industries have in turn examined how

employers, to ensure the performance of aesthetic labor, actively encourage

(especially female) workers to cultivate particular embodied dispositions

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

297

Sallaz

(Dean, 2005; Hanser, 2008; Pettinger, 2005; Warhurst & Nickson, 2007;

Williams & Connell, in press; Wissinger, 2009; Witz, Warhurst, & Nickson,

2003). As illustrated by these studies, the value of the habitus concept is that

it expands our purview beyond the labor process, on to the larger field of

experiences and meanings that workers bring with them into the workplace.

What though of the other key elements of Bourdieus theory? Do they also

hold potential for advancing our understanding of the dynamics of contemporary service work? This article considers the relevance of Bourdieus political sociology for elucidating new objects of inquiry at the point of production.

It commences, in a section called Labor and Representation, by reviewing

the corpus of Bourdieus writings to see how he analyzed the subject of labor.

Over the course of his career, I conclude, Bourdieu moved away from arguments about the habitus and work organization to establish the principles of

a general sociology of symbolic power. At this point, the article critically

interrogates three key assumptions of the sociology of service work through

the lens of Bourdieus political-cultural sociology. Doing so provides a

framework for analyzing the actors and strategies involved with the symbolic

struggles that undergird even the most basic bread-and-butter issues at

work.

The second half of the article shows how Bourdieus political sociology

may be put to work. It presents qualitative data drawn from my own ethnographic study of labor inside a large entertainment complex in contemporary

South Africa. It was during such fieldwork that I discovered a puzzle. Rather

than seeking to encourage emotional labor, managers in this competitive

tourism industry refused to label employees interactive work as service.

In turn, workers actively advocated for such a designation. Such struggles

over the definition of workers labor were not peripheral to, but rather were

key elements of, the larger production regime. We thus conclude by elaborating on the relevance for the sociology of work of one of Bourdieus key

ideas: that of the nomination struggle in situ.

Labor and Representation

From Earthly Labor to Symbolic Power: The

Trajectory of Pierre Bourdieu

How can the theory of Pierre Bourdieu be used to advance our understanding

of service labor? Insofar as Bourdieu himself never explicitly addressed the

subject, we are required to do a brief excavation of his overall body of work.

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

298

Work and Occupations 37(3)

What follows here is my own interpretation of this corpus, based on close

reading of all available English translations of his books and articles. I argue

that, for our purposes, this body of work can be divided into three phases:

first, early ethnological studies of work in the colonial context (especially

Travail et Travailleurs en Algrie, published in English as Algeria 1960 in

1979); second, a series of monographs on culture and fields in modern France

(Distinction in 1984, representing the crowning achievement); and third, a

public sociological critique of globalization and neoliberalism (works such

as Firing Back in 2003). The overall picture to emerge is of a shift from

analysis of work in its local context to that of culture in a global context.

Bourdieus first major research project was an ethnological study of the

rural Algerian people known as the Kabyle. They lived, Bourdieu argued, in

an undifferentiated social space without autonomous fields such as universities and labor markets (Bourdieu, 1977). As a consequence, their schemes of

perception, or habitus, were traditional; they were attuned to the past and

generated in the Kabyle people a desire to conform to inherited models

(Bourdieu, 1979, p. 9). On a day-to-day basis, this meant that labor (of which

the tasks of farming were primary) was performed as it had been for centuries

before. But this system was disrupted by French colonization. Forced off the

land, the peasant migrated to the city where his traditional habitus proved to

be ill equipped for a modern economy. He was unable to imagine his labor

power as a commodity to be sold at market nor could he accumulate savings

to plan for periods of unemployment. Like the proverbial fish out of water,

the newly urbanized peasant fell into a traditionalism of despair.

After returning from Algeria, Bourdieu began a series of studies of modern France as an example of what he called a differentiated society, that is,

a social world characterized by multiple fields and species of capital (cultural, economic, etc.). Dispositions still mattered. For instance, in Distinction

(Bourdieu, 1984), his monumental study of consumption and taste, Bourdieu

depicted modern France not as a static social order oriented toward fidelity to

the past but as a dynamic game of culture. Artists continually vie to outdo one

another with formal innovations, resulting in a permanent revolution of

cultural forms. But to enter this game in the first place, one must have experienced a particular form of socialization: a childhood in which one was

assured of having ones basic material needs met. Working-class children, in

contrast, endure scarcity and hardship, resulting in a taste for necessity that

hinders their ability to play the games of culture found in the various elite

fields.

In general, however, fields are autonomous spaces, such that the cultural

games played within them are rarely overdetermined by material constraints.

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

299

Sallaz

In fact, the work of artists, politicians, and other professionals is characterized by nuanced strategies of framing, categorizing, and classifying symbols.

It was one of Bourdieus enduring contributions to elucidate these strategies

and the principles underling themto expose, that is, a modern economy of

symbolic power. Curiously though, the world of work for the most part

escaped his gaze. His empirical studies focused on the education system

(Bourdieu & Passeron, 1979), the political field (Bourdieu, 1996), the art

world (Bourdieu, 1993), and housing markets (Bourdieu, 2005). It was not

until the end of his career that he would return, if but briefly, to the subject of

work.

In what I label Bourdieus third phase, he assumed the role of public intellectual to critique the global spread of neoliberal ideology. Emanating from

the United States, this ideology demands the simultaneous withdrawal of the

state from the realm of the social and the ascendency of market forces as the

ultimate arbitrator of value and exchange (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1999). In

works such as The Weight of the World (Bourdieu, 1999b), Bourdieu speculated as to how neoliberalism affects workers, trade unions, and the working

class as whole. Once more he invoked his dispositional theory, now to explain

how workers respond to the economic precariousness produced by

neoliberalism:

Insecurity acts directly on those it touches (and whom it renders incapable of mobilizing themselves) and indirectly on all the others,

through the fear it arouses . . . [These are] the prerequisites for an

increasingly successful exploitation of these submissive dispositions

produced by insecurity. (Bourdieu, 1998b, pp. 82-83)

As this summary shows, Bourdieus work, although it neglects to consider

explicitly the structuring of service labor, is replete with possible lines of

inquiry.

A Sociology of Representation: Nomination Struggles at Work

This article expounds on one of Bourdieus key theoretical contributions: his

analysis of the symbolic politics of nomination struggles. There is of course

an excellent branch of research examining how workplaces can be sites of

contention over meanings, identity, and dignity (Hodson, 2001; Lopez, 2006;

Sherman, 2010; Vallas, 2006). Room exists, however, to flesh out in full how

Bourdieus work on symbolic representation allows us to analyze the workplace as a site of micro-political contestation over the existence and meaning

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

300

Work and Occupations 37(3)

of service work. In brief, I argue that scholars too readily take for granted

the existence of service work as a category of analysis. They prematurely

black box the notion, thereby neglecting to consider that the very concept

can be a stake of contestation on the shop floor.

To elaborate, the emergent sociology of service work makes three assumptions that are problematic from a Bourdieuian perspective. First, that service

work (or some similar term) is a self-evident concept that can be defined a

priori by the analyst. The typical work in the field begins by offering a new

label and definition for the phenomenon under consideration. Hochschild

(1985), for instance, introduces the term emotional labor and defines it as

work in which management attempts to control a customers feelings by controlling a workers emotional displays. Leidner (1993) in turn uses the term

interactive labor to denote all employment in which workers have face-toface or voice-to-voice contact with clients. Each then proceeds from their

initial definition, through a series of modalities (i.e., logical operators that

assume the validity of the initial premise or concept; see Latour, 1987), and

onto a set of empirical conclusions.

Bourdieu, in contrast, argued that there may occur definitional struggles to

establish wherein lie the boundaries between formal work and other forms of

labor. The task of the sociologist is hence to objectify objectification: to

take as ones data the history behind any given system of classifications

(Bourdieu, 1984, p. 7). In Practical Reason (1998b), he gives the example of

an attempt by altar boys in the Catholic Church to form a union. The courts

denied their claim, arguing that a church is not to be considered a business

entity nor are those who labor inside it to be thought of as employees. And in

the United States, there is ongoing debate as to the legal status of home health

care aides. Currently they are classified as companions, not employees,

and so are eligible for neither protections such as those provided by minimum wage legislation nor benefits such as overtime pay. As these examples

demonstrate, work can be a stake in struggles to mobilize symbolic power.

Actors will seek to grant or deny to a particular activity the title of work:

a being-perceived guaranteed as a right (Bourdieu, 1999a, p. 239). By

implication, just as the work/nonwork boundary can constitute a site of struggle so too may the work/service work boundary (Sherman, 2005). When does

a form of labor constitute service? When will key actors (especially workers and management) seek to advance, challenge, or defend such claims?

Such questions lead to our next extension.

A second common claim made by sociologists of work is that service will

represent an additional demand imposed by management on workers. All

forms of labor, this reasoning goes, will involve some noninteractive

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

301

Sallaz

duties. Both forklift drivers and flight attendants transport heavy carts up and

down aisles. Both chemists and barristas pour hot liquid from one flask into

another. Service workers, however, face an additional layer of responsibility:

that of managing their emotional expressions so as to generate in customers

an appropriate feeling state. The classic example is Hochschilds (1985)

comparison of an 18th-century child factory laborer with a modern flight

attendant. The former was likely estranged from his body insofar as his muscles and tendons were gradually worn down to produce profit for someone

else. The boys emotions, however, were safely his own. The flight attendant,

in contrast, sells not only her physical labor power but also her capacity to

engage in emotional labor. As capitalism steadily pulls emotions into the

realm of commodity production and circulation (what Hochschild calls a

transmutation of emotion systems), service workers are at hazard for not

simply physical alienation but emotional alienation as well (Grant, Morales,

& Sallaz, 2009).

When viewing work through a Bourdieuian lens, service appears not as

an additional claim placed on workers but as a potential counterclaim to be

made by workers. Symbolic acts of nominationthat is, moves to classify an

object as a certain sort of thingare also always acts of claim making

(Bowker & Star, 2000). By lobbying the government to label the labor of

home health care workers as formal employment, advocates seek to guarantee these workers an array of rights and material benefits, ranging from

protection against discrimination to social security eligibility. But can the

same hold for achieving the official label of a service worker? Although

state agencies such as the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics use a variety of

schemata for classifying different forms of work, regulatory systems rarely

draw a significant distinction between manufacturing and service jobs for the

purpose of determining rights and benefits. Nonetheless, this does not rule

out the possibility that at the level of the individual enterprise or workplace,

symbolic struggles (with very real stakes) may take place over the service

work label. But to analyze such micro-political struggles requires that we

consider as well the issue of managerial action within economic fields.

This brings us to a third extension that can be brought about by a

Bourdieuian perspective. This one problematizes the assumption that decision makers within a firm, when planning work routines and requirements

regarding service, operate in line with a basic economic logic of product

differentiation. The various strands of scholarship on service work are here in

agreement that competition will beget a demand for high-quality customer

service. Industries in which some entity possesses a monopoly on the goods

or service will provide managers with little incentive to induce a service

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

302

Work and Occupations 37(3)

orientation in workers. Consumers are a captive market, whereas training and

monitoring costs for emotional labor are not negligible. The paradigmatic

example is the government post office, universally reviled for its long lines

and its workers surly demeanors. In contrast, competitive industries should

use quality service as a means of product differentiation. If consumers have

a choice as to where to purchase an item or service, all else (especially price)

being equal, they will choose the firm that offers them the most pleasant

experience.

But Bourdieus (2005) own work on the contemporary economy argues

that industries resemble less competitive free markets than complementary

fields of production. Dovetailing with recent approaches in economic sociology (Fligstein, 2002; Podolny, 2008), Bourdieu (2005) depicted economic

fields as stable structures wherein dominant firms establish the rules of the

game, whereas smaller firms must be content to occupy peripheral niches.

Producers share a common understanding of how firms will compete with

one anotherconcerning, that is, those aspects of the production process that

will be standardized versus those that can be manipulated by managers. And

what are the implications of these arguments for the study of service work?

In brief, rather than viewing service as an abstract commodity, we should

seek to delineate the specific meaning it has for managers, workers, and consumers. Such meanings, furthermore, must be situated in relation to the history and structure of the particular field under consideration.

Service Struggles in South Africa

To illustrate the utility of a Bourdieuian approach to studying service work, I

present evidence from one of my field studies. It was a case in which ongoing

conflict occurred between workers and management over the status of the

tasks performed. Each side advanced claims as to whether or not it was

appropriate to label such tasks as customer service. But there was no final

recourse to an outside entity (such as the state or an appropriate labor bureau)

nor could either side mobilize sufficient symbolic power to settle the issue

once and for all. The result was a stalemate and ongoing hostility between the

two sides.

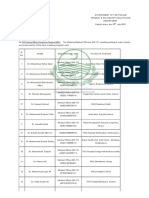

The field site was a large entertainment complex in the city of Johannesburg, South Africa. It contained a hotel, shopping mall, casino, and several

food courts. Fieldwork was conducted over the course of two ethnographic

stints, one in 2001-2002 (a 9-month research project) and the other in 2006

(a 3-month site revisit). As these dates indicate, all fieldwork was performed

during South Africas post-apartheid period (White rule ended with the 1994

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

303

Sallaz

electoral victory of the African National Congress, or ANC, over the incumbent National Party). The author was granted access to the field site as an

official intern of the company, called herein Empowerment Inc., that

owned the complex, called herein Rainbow City. (Because operation of

several of the retail outlets and restaurants in the complex was outsourced to

other firms, the analysis herein is restricted to employees of Empowerment

Inc.; these workers constituted 80% of the workers on-site at any given time.)

Several characteristics of the site, firm, and workforce are relevant for

understanding the subsequent struggles that emerged around the classification

of workers labor as a service job. The firm, Empowerment Inc., had been in

operation since the late 1970s. It had operated resorts throughout rural South

Africa during the apartheid era, and most of the current managerial employees

were Whites who had been with the company for 10-plus years. (Blacks had

been informally barred from managerial positions during apartheid, in line

with what was known as the color bar.) Following the end of White rule, the

firm had been permitted to continue operations in South Africa but only on

condition that it adhere to a strict plan for Black economic empowerment

specifically, a nationwide system of numerical quotas for hiring previously

disadvantaged individuals into low-level positions throughout the organization (Webster & Omar, 2003). This category included all those typically considered service workers in the literature, such as food servers (Paules, 1991),

casino dealers (Goffman, 1982), and cashiers (Smith, 1992).

The work performed by these employees certainly seemed to meet all the

scope conditions for an emotionally demanding service job as specified in the

literature. Workers engaged in face-to-face encounters (i.e., interactive labor)

with clients, and the emotional state of these clients was considered by management to be important. Diners, for instance, were to leave the restaurants

content, losing gamblers consoled, and so on. And as a firm operating in a

competitive urban marketplace, Empowerment Inc. actively promoted in its

marketing material the idea that guests would have an unparalleled, worldclass leisure experience. Given such conditions, we would be justified to say

that the sociology of service work would predict managers to require workers

to perform customer service for clients.

But allow me to report the following empirical puzzle: This prediction did

not hold true. Managers did not ask workers to perform service for clients. On

the contrary, managers vehemently denied that workers should play any sort of

role in the process of creating for clients an enjoyable experience, whereas

workers actively sought to claim an identity as a service worker. What is

interesting is the issue of what sort of stakes each side saw as up-for-grabs in

such symbolic struggles over the nature of service as well as the strategies they

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

304

Work and Occupations 37(3)

used to pursue these stakes. In short, the very definition and relevant properties

of service constituted an active battleground at Rainbow City.

Service Is Shit in South Africa: Managerial Mythology Laid Bare

Let us start by considering managers. All top executives with Empowerment

Inc. were veteran White employees of the company and thus had decades

worth of experience running leisure resorts in southern Africa during apartheid. Many looked back at this time as a golden age in which the oversight of

a leisure resort was relatively easy. On one hand, the lack of state regulation

allowed the firm to routinely discriminate against Black staffa service sector counterpart to the racial Fordism that characterized South African

industry generally (Webster, 2002). On the other hand, the firm regularly

recruited experienced professionals from Europe to manage its properties. In

a given resort, a renowned chef from Germany might head the kitchen,

whereas an experienced croupier from London would direct the action on the

casino floor. Corporate executives trusted that these expats would ensure the

quality of goods and services. The firm, in short, had no explicit service philosophy or policies; it decentralized customer service routines to propertylevel managers.

Following the fall of apartheid, new labor legislation specified that the

general workforce and property-level management must be diversified in line

with a larger Black Economic Empowerment plan (Buhlungu, 2009). As for

incumbent White staff, a few were promoted into the ranks of corporate management, a few were able to retain their positions, but most resigned. At this

same time (the mid-1990s), Empowerment Inc. executives began a thorough

review of corporate policy and procedures regarding marketing issues. It was

decided that the company needed a new brand identity, and after several days

of brainstorming, executives came up with a new motif emphasizing fun,

excitement, and festivities. A corporate mission statement was drafted, containing a series of principles putting the guest at the center of everything

the organization does. At the Rainbow City Resort, posters were placed

throughout the back of the house areas (such as the cafeteria, near the

employee time clock, and in the break-room) extolling the virtues of giving

world-class service to guests.

The executive managers I interviewed and observed during my fieldwork

appeared to have completely bought into this new idea that customers emotions were now something to be managed by the firm. They spoke of those

who came to the resort to gamble as depressed individuals who needed to

be distracted and cheered up. They spoke matter-of-factly about the new

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

305

Sallaz

imperative to provide the hotels guests with a world-class leisure experience. And they proudly displayed on their desks bronze plaques bearing

phrases such as The customer is always right.

But beneath this general rhetoric, there was something curious about how

managers went about creating a positive experience for guests: They believed

that customer service on the part of the firms frontline employees was to

play no part in it. Consider the following quote from the manager of Rainbow

Citys slot machine division. He is describing a new plan to generate enthusiasm among gamblers at the casino:

MGR: We got this new promotion event planned, we call it Lucky Slot

Madness. Everyone will be sitting there playing their machines,

when at some point in the night there will be a great commotion and

all the lights on all the machines will start flashing. One by one, the

lights will go off until theres only one left on, and this will be the

winner. The lucky slot.

JS: So whats the point of that? What do they win?

MGR: Oh something small, just a bottle of wine or something. The

important thing is that it will create a sense of excitement.

As this manager narrates an upcoming event, he illustrates that the firm has

dedicated significant energy to planning how to manipulate the consumers

emotions and overall experience. But notice too what is absent from this narrative: workers. All the operators intended to manipulate consumers (lights,

music, wine) are objects, not persons. This is puzzling given that workers

saturate the complex and are an obvious conduit for facilitating firmclient

contact. Here though lies the rub: managers explicitly removed customer service from the overall formula of experience-production. The words, demeanor,

and appearance of workers were all to be neutralized, not accentuated.

Managers explained their denial of employees service potential in several

ways. Most were essentialist arguments concerning the inability of Black

workers to provide quality customer service. For instance, and as the companys operations director explained to me in an informal conversation:

The African mentality is that they deserve something for nothing.

Theyve been a bartender for two years and expect to be promoted to

food and beverage manager. Back in the U.K., youll find an old man

who has been tending bar for 20 years and can give good service to

400 people. Here you can assign 400 Blacks to work a bar serving one

person, and theyll still find a way to muck it up.

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

306

Work and Occupations 37(3)

Another executive stated,

If youre a Black guy doing a service job, youre dreaming of being a

manager in a big office with nice carpet. Youre not thinking about the

job at hand, and youre definitely not thinking about the needs of the

customer standing there in front of you.

The general accusation conveyed by these quotes is one of a cultural incompetence, induced by a lack of patience and undue expectations. Several managers specifically mentioned culture when I asked them directly why they

dont ask workers to perform customer service. Its culture, all the obstacles,

they just dont have the tools. Consider as well the following statement, in

which workers standards of cleanliness are mocked:

Well weve met our equity quotas, exceeded them actually. The [provincial regulators] are happy, as weve even got 30% of our workers

from a nearby squatter camp. You cant even imagine how tough this

has been. We give them brand new white tuxedo shirts, and they go

home and wash them in the dirty little river. Now everyone is wearing

brown shirts! Just bloody brilliant.

Another line of argumentation specified that workers, even if they were

capable of providing quality service, would not want to. Black workers

resent having to do the service thing, one hotel executive stated, Especially

if the customer is White and wealthy. All sort of bad associations are brought

up. Here, the executive is referencing the status order of apartheid, wherein

those classified as Black were expected to exhibit deference to Whites in

everyday interaction. It is important to note too that managers claims regarding service expectations did not extend down to customers themselves. It is

true that clients of the Rainbow City entertainment complex (the majority of

whom were White) could no longer expect Black workers to be completely

servile in their demeanors. But, on the other hand, many expressed frustration that workers were not encouraged to provide any sort of service at all.

The final result of managers myriad truth-claims regarding workers service abilities was an adamant denial that customer service can or should

function as a means of product differentiation in the industry. For instance, in

an interview with the CEO of one of Empowerment Inc.s rival companies, I

had the following exchange:

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

307

Sallaz

JS: So what steps does your company take to get workers to provide

good customer service?

CEO: [chuckling] Look, service in South Africa is shit. Its as simple

as that. Of course we all have an imagination that there would be

ideal service like there is in New York or Las Vegas.

JS: And what does that mean, ideal service?

CEO: Where you sit down at say a blackjack table, and within a minute, a waitress has come over to you, she smiles, and takes your

order for a drink. Or when you get to the hotel reservation desk, and

the clerk greets you and makes conversation.

AU: But those sort of things, they dont happen here?

CEO: No, and I cant see them ever.

To summarize the argument thus far: sociologists of work predict that, in

competitive industries, a positive consumer experience will become a means

of product differentiation, whereas workers service will be a part of such

differentiation strategies. This is a straightforward and logical hypothesis,

one in accordance with basic economic principles. But my findings from the

leisure industry in contemporary South Africa present an anomaly: They

validate the first part of this argument but not the second. The leisure industry

in Johannesburg is undoubtedly competitive. And executives within the firm

I studied have recently come to see a positive guest experience as an essential part of their marketing plan. Today, they actively strategize ways to control and manipulate clients emotions. But managers refuse to acknowledge

worker service as a possible means for doing so. Interviewee and interviewee

voiced a fatalistic resignation to the fact that service in South Africa is shit,

to invoke the fecal metaphor mentioned above. When pressed to justify this

argument, they referenced the abilities and desires of workers. Blacks,

their argument went, were unable and/or unwilling to perform service for

clients.

Workers themselves, however, had a different take.

But We Are Service Professionals! Workers Counterclaims

Did managers arguments accurately reflect the capacities and desires of

workers? Based on my cumulative fieldwork observations, I argue not. On

repeated occasions, and in various forums throughout the leisure resort, I

witnessed workers challenge managerial claims. Nor were these isolated and

idiosyncratic events, as these counterclaims were patterned and displayed a

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

308

Work and Occupations 37(3)

definite logic. The goal of this section is to use Bourdieus political sociology

to illuminate and interpret these patterns. The overall picture to emerge is of

Rainbow City as a veritable battleground for symbolic claims over the meaning of seemingly commonplace notions such as customer satisfaction, service work, and professionalism.

Management depicted workers as constrained by various elements of their

culture. The three tropes most commonly used were that of the uppity

Black who was too busy dreaming of an office job to concentrate on service,

the incompetent Black who lacked the tools to relate to the firms respectable clientele, and the angry Black who would be offended if asked to

prove service. In reality, though, most workers fit none of these stereotypes.

The 2,000-plus employees of Rainbow city were primarily Black South Africans, and they were diverse in terms of gender, age, and prior work experiences. For many, it was their first job, and some surely did lack the skills that

would be necessary for world-class service (such as the new restaurant

server who was only partially fluent in English or the cocktail waitress whose

body type failed to meet managers expectations concerning ideal standards

of beauty). But few workers viewed service as inherently difficult or

demeaning. On the contrary, the typical worker with whom I interacted was

open to the idea of providing service and to a more general conception of

service professionalism.

Workers claims to a service identity had both material and ideal bases.

For instance, one issue around which service disputes often crystallized was

the companys tipping policy. In the late 1990s, Empowerment Inc. decided

to ban tipping throughout all of its South African properties. Signs were

posted notifying customers that they were not to offer gratuities to workers.

Today, if a worker does receive a tip, he or she is required to hand it over to

a supervisor, with the money then going into the propertys general revenue

account. Cameras and security guards monitor workers to insure that they do

not surreptitiously keep a tip; workers found guilty of doing so are considered guilty of theft and could be dismissed.

Not surprisingly, the no-tipping policy was unpopular with workersand

customers too. It would not be an understatement to say that both groups

thoroughly despised it. For example, I attended a monthly staff meeting held

in the large arena usually reserved for concerts and boxing matches. During

the question-and-answer period, a female casino dealer stood up and asked

the property manager: I just want to know one thing. Where do our tips go?

They should be mine! From the staff came sounds of clapping and shouts of

support: You go girl, Uh-huh, you tell them. The manager responded by

taking the microphone and explaining to the room that tip income is quite

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

309

Sallaz

volatile, whereas the companys flat wage provides a stable income. Some

days, workers make lots of tips but some days they make hardly any. Nor,

he explained, do workers now have to worry about kissing up to people.

For these reasons, the no-tip policy was actually in workers best interest. The

young woman was not satisfied, however. She stepped back up to the microphone and declared, But I am here to be a service professional. This policy

makes me unhappy, and if I am not happy then the guest is not happy!

This interaction, reported verbatim, illustrates well how conflicts between

management and workers over bread-and-butter issues played out in relation

to the issue of service. It may also be considered a classic example of a nomination struggle in situthat is, an interpersonal joust to impose a binding

definition on an otherwise unnamed phenomenon. To start, the worker is

making a claim in which are linked a series of items. First, she has expropriated and endorsed the official company rhetoric (expressed throughout the

workplace) concerning the importance of customer satisfaction. Clients are

guests whose emotional happiness is integral to the organizations success. In direct contrast to managerial thought, which considers its own actions

as the sole instrument for affecting clients (through means such as music,

contests, and alcohol), Suzanne is inserting into the equation a new (independent) variable: the service provided by employees such as herself. In this

context, good service can be said to possess a positive or downstream

modality (Latour, 1987, p. 23) insofar as it is rhetorically framed as a necessary prerequisite for the subsequent production of customer satisfaction (If

I am not happy, then the guest is not happy).

But Suzannes truth-claim concerning customer service can also be said to

possess an upstream modality. To take the claim seriously on its own terms

requires moving back in time, to reconsider the origins of a corporate policy

already in place. The companys practice of prohibiting and confiscating tips

makes her unhappy because it is an unfair theft of what is rightfully hers. Her

anger and unhappiness are thus justified through reference to a series of more

general principles of equity (Boltanski & Theverot, 2006). Who could be

cheerful and give good service when one is the victim of an ongoing crime?

As logically sound as Suzannes argument was, it could not but fail to

prevail insofar as it rested on an assumption to which managerial thought was

hostile. This assumption was precisely that workers emotional labor could

influence customer satisfaction. Managers practical logic assumed that no

matter how hard a Black tried (if he or she tried at all), the service provided

would be of an inferior, ineffectual, and sullied sort. But it is important to

examine precisely how the property manager attempted to counter Suzannes

claim. It would have been entirely inappropriate to articulate this racialized,

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

310

Work and Occupations 37(3)

stereotypical assumption publicly (thereby risking a discrimination claim or

lawsuit). Instead, he sought to counter the truth of the upstream claim, the

one equating the no-tipping policy with theft. Far from being an unwarranted

act of larceny, the manager argued, the policy is actually an act of benevolence. Because tip income fluctuates, the company wants to make sure that

workers are able to rely on a guaranteed income source. Hence, they should

not be unhappy or upset about the policy. (Of course, workers were not consulted about this policy change nor is it apparent why they could not both

receive a stable salary and accept tips.) It should also be pointed out that the

no-tipping policy was highly unpopular among clients. On several occasions,

I witnessed a gambler, on winning a large bet at a roulette table, tell the dealing staff that he or she would be happy to meet them down the road, at the

petrol station, after work. The underlying message was that a tip would be

handed off in a clandestine location, so that workers could be rewarded for

the good dealing service they had provided the bettor.

In addition to tipping, a second common point of contention between

managers and workers centered on what I came to label managements Disney hypocrisy. Ill provide some background. During the period in which

top management decided to implement a consistent, company-wide service

philosophy, Empowerment Inc. established a multiyear contract with the

Walt Disney Company. Disney advisors traveled to South Africa and assisted

with planning and theming the companys properties. They also gave several

presentations to the workforce at Rainbow City about the importance of customer service. Although employees may often view such seminars with cynicism (Kunda, 2006), workers at Rainbow City seemed not to have viewed

them as corny or just company speak. On the contrary, they were enthusiastic to hear about the Disney service philosophy, and many appeared to

have imbued it with an emancipatory meaning. They appreciated how it

framed employees as the companys most valuable asset as well as its emphasis on empowering frontline workers to take responsibility, make independent decisions, and engage in positive, respectful interactions with clients.

For many workers, it was the first time they had ever heard such rhetoric. It

certainly had not been found in any workplaces (service or otherwise) during

apartheid.

At the time of my fieldwork, a full 2 years after the contract had ended,

Rainbow City employees still regularly referenced the Disney experience.

It represented a powerful symbol of the inconsistency between the official

rhetoric of service and the reality of managerial practice at Rainbow City.

Although many current workers had not been present at the original presentations by Disney consultants, there was another vehicle through which Disney

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

311

Sallaz

memories were kept alive among the workforce. For, as part of the contract

with Disney, Empowerment Inc. had allowed a group of around 20 Rainbow

City workers to perform internships with Disney at the companys entertainment empire in southern Florida. These entailed spending a year in the United

States and working at a variety of service jobs at the Magic Kingdom. The

idea at the time, as internees understood it, was that they would acquire

hands-on experience with the Disney service philosophy and then return to

South Africa to assist with implementing it at Rainbow City. And although

this may even have been the original intention of the company executives

who inked the deal, workers were disappointed to find on their return that

property-level managers were not too interested to hear about the Disney

Way let alone make major alterations in how they ran their facility.

Though disappointed, the former interns experienced a new role and newfound status among their coworkers. For they constituted living proof that

there was no inherent flaw in the Disney service programit did exist in

concrete reality, in the United States. The fact that workers were not treated

as service professionals in South Africa could thus be attributed to ulterior

motives on the part of entrenched managers. In effect, the Disney interns

became powerful spokespersons for the workforce as a whole. Their individual stories and complaints came to represent the hopes and frustrations of

all employees. For instance, when I first began fieldwork in Rainbow Citys

marketing department, workers repeatedly referenced Disney as evidence

of the companys hypocrisy. When I would inquire further, they would tell

me that I should go and talk to Nombuso, a current employee in the hotels

call center, because, as one worker stated, she has been there and seen it

with her own eyes. I was eventually able to make my way down to the call

center, and arranged to have lunch with Nombuso later that day. Over our

meal, she told me her tale.

They All Need to Go to Disney: Nombusos Story

Nombuso (a pseudonym) is 26 years old. She is from Soweto (short for

southwest township), a large Black settlement of more than one million people, not too far from the Rainbow City complex. Her father had been a taxi

driver before passing away in 1998. Her mother still lives in Soweto and

makes a decent living as a dressmaker. Nombuso has obtained a fairly high

degree of education. Because her parents had both kept steady work during

her childhood, they had been able to send her to a private secondary school.

She graduated in 1995 and was accepted into a 1-year hotel management

course in 1996 (as part of the first class that accepted Black students). She

completed the course with honors and in 1997 was hired to be the assistant

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

312

Work and Occupations 37(3)

chef at a Japanese restaurant in a suburban Johannesburg mall. After 6 months

of trying unsuccessfully to learn how to slice sushi, Nombusa received a job

offer from a large hotel chain based in Pretoria. She took the job but soon

grew bored and dissatisfied, as she spent the majority of her time doing routine labor as a switchboard operator. This, she says, was not what I went

to school for.

It was at this time that Nombuso registered with a staffing agency. It

arranged for her an interview at the Rainbow City resort, and she was offered

a job in the marketing department in the spring of 1999. I was so excited

yippee!that when they called me on Friday to offer me the job, I said I

wanted to start that very next Monday. At first, she was put on the switchboard again, receiving and directing calls, but soon her portfolio of tasks was

expanded. She helped to design organizational flowcharts for the human

resources department and received some basic photography lessons while

assisting with the design of marketing material. Then came the day she saw a

notice on the employee bulletin board advertising available internships at

Disneyworld in Florida. She submitted her resume to the HR coordinator and

was one of four Rainbow City staff to be selected for that round (she is not

sure how many had applied total). They left in early 2001 on 1-year

contracts.

I asked Nombuso why she thought that the company had been willing to

release her to do the Disney internship. She replied that the HR coordinator

here at Rainbow City had told her that the program was being run through

corporate and that they were sincere about sending some promising staff persons over to the United States, to learn Disneys techniques and philosophy

of customer service. They really did want to become known as a global,

world-class service company.

Nombuso recounted for me her first reaction to the Disney system as well

as her impression as to how it compared with the companies shed worked

for in South Africa. First off, she answered, I have nothing negative to say

about my experience at Disneyworld. She spent her first 3 months learning

how to do event planning on a Disney cruise ship. She performed so well at

this job that her next assignment was as a bussing coordinator at the Epcot

Center theme park. Nombuso is charismatic and gregarious, and 6 months

into her internship, she received an award for her customer service skills

(cast member recognition, as its called). By the time her internship in Florida ended, she was herself training new interns in the Disney principles of

good service.

The Disney style of management had been entirely new to her. They

actually encourage you to take initiative, to think independently. Most of her

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

313

Sallaz

supervisors had been young, like her, and not as concerned with power or

status. Furthermore, an open-door policy was the norm, which you would

never find here. And of course there were rules, but they were more like

guidance. I mean, this was a place where you could be free! As a tour operator, shed often had peoples lives in her hands. This proved how much trust

management placed in her and gave her a great sense of responsibility and

confidence. At Rainbow City, in contrast, she had to run to management

for clearance to do anything. This difference, Nombusa says, was puzzling,

because most of her managers at Disney were White, but they didnt act as

did the managerial staff at Rainbow City, that is, very formally. In general,

she labels the latter as insecure and too concerned with discipline.

It was like I was living in a dream, because I had to wake up. So Nombuso described her return to South Africa. Even though she had been assured

that leaving to do the internship would not negatively affect her employment

with Empowerment Inc., she discovered that her old job had been filled, and

the company had not arranged a new position for her. She talked to the marketing department head, who explained to her that because of financial pressures they could not create for her a new spot nor could they credit her work

history so as to grant her the small annual wage increase that other employees

had received. For the year prior to our interview, she had been floating

around the resort, filling in for sick employees or on busy days. Even worse

than this lack of a clear role, nobody [in management] wanted to talk to me

[about the Disney experience]. Nombuso requested meetings with the various department heads to describe in detail how the service philosophy worked

in practice at Disneyworld. More important, she wanted to show them the

formal assessments she had brought back with her from Disney, attesting to

her excellent service skills. But no one would commit to a time to meet with

her, and to this day the assessments sit on a shelf in her kitchen. This all has

left Nombuso quite disenchanted: It is the opposite of the open-door policy.

They all need to go to Disney.

Unable to talk to her managers, Nombuso shared the story of her experience overseas with her coworkers. They were anxious to hear any news at all

about life outside of South Africa and listened intensely to her tales about the

culture of service professionalism at Disney. Later, I spoke to other former

Disney interns at Rainbow City, all of whom reported both a lack of interest

from managers and high levels of interest from their colleagues on returning

from the United States. In the marketing department today, Nombuso enjoys

a special status as one who could speak to managers with a degree of authority concerning their hypocrisy in regard to service. And she readily accepts

the role of spokesperson, a representative who embodies and gives voice to

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

314

Work and Occupations 37(3)

the discontent latent in the workforce as a whole. Hence I, as were many new

employees at the resort, was advised to go see Nombuso to learn about

Rainbow Citys hypocrisy.

Analysis and Implications

This article commenced with broad and all-too-brief overviews of both Pierre

Bourdieus theory and the emergent sociology of service work. We divided

Bourdieus work into broad phases: an initial ethnology of the intransigence

of habitus in the colonial labor market, a series of empirical monographs on

culture and stratification in France, and finally, a public sociology in opposition to global neoliberalism. We then laid bare several key assumptions of the

service work literature: notably, that good service is an unproblematic,

even a priori, category of thing and that managers in competitive industries

will have an interest in asking workers to provide it. Admittedly, both of

these summaries are guilty of oversimplification. Exceptions and counterreadings could easily be found for every component of each. Nonetheless, I

judged it worthwhile to make such generalizations to expose fruitful points

of dialogue between the two theory/research programs.

The two theories were then taken into the field, as I reported on a major

ethnographic project within a leisure resort in postcolonial South Africa.

Somewhat surprisingly, it was not Bourdieus well-worn concept of habitus

that proved most relevant for understanding the labor regime found therein

nor was it the service work literatures overarching concern with emotional labor

management. Rather, it was Bourdieus theory of political representation

and in particular the notion of nomination struggles. For this was a workplace

ripe with ongoing struggles to define the very nature of service. During a year

of fieldwork at Rainbow City resort, I found that there was no consensus that

the labor performed by employees was service work (and even though it met

the basic definitional standards found in the literature, such as face-to-face

contact with clients). Workers sought the label service professional and,

following a presentation by Disney consultants, actively promoted the idea of

a customer-centric organizational philosophy. Management, however, sought

to remove workers from the customer service equation. They defined workers as background equipment, more akin to manual laborers than to qualified

service professionals.

Symbolic struggles such as these are not exceptional and inconsequential;

they can have important material effects. For instance, workers at Rainbow

City strove to constitute themselves as service workers in order to reform the

companys tipping policy. But they also, as Nombusos story illustrated,

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

315

Sallaz

recognize that service worker is a title that carries at least some connotations

of honor and responsibility. To name an activity a service is to attach to it a

series of other claims, such as respectful treatment of the workers providing it,

professionalism, autonomy, and a concern for the emotional well-being of both

worker and client. And to deny that a form of work is service is to repudiate

such claims. As a principle, we as researchers should be on guard against preestablishing a definition of service work. Such premature naturalization may

be warranted but never at the risk of being blind to the very real symbolic battles that may occur over how work and service are defined and

categorized.

Such classification struggles can themselves by classified. At one extreme

are informal, interpersonal disputes over character and identity, the paradigmatic example being that of an insult shouted in the heat of the moment

(Youre an idiot!). At the other extreme is the power of the modern state to

confer legitimate titles. The current debate in the United States about the

status of home health care workers illustrates well this fact, as it features

social movements, employers, unions, and other groups lobbying to have this

form of labor classified (or not) as formal employment. The state, as the

holder of a monopoly of symbolic power, represents the ultimate arbiter of

struggles to name and classify.

The conflict at Rainbow City over whether or not employees could claim

the title of service workers did not fit either of these extreme positions.

Workers claims were not spontaneous or individual outbursts. By the time of

my arrival, they had been somewhat institutionalized, with workers regularly

using phrases such as I am a service professional during conflicts with

management and with the emergence of particular spokespersons (such as

Nombuso) representing the widespread discontent among workers. But on

the other hand, there was no obvious authority beyond the workplace to

which one side or the other could turn for final resolution of the dispute. The

state in South Africa does make a distinction between manufacturing and

service workers but only for the purpose of collecting statistical information

on the economy. No worker I encountered was aware of these governmental

statistics nor does the state use this classificatory system to confer special

rights on certain categories of workers (Seidman, 2008). Institutionalized yet

lacking a final arbiter, symbolic struggles over service were at a stalemate.

Although neither side could declare a final victory, the balance of forces

undoubtedly favored management, which resolutely refused to label or treat

the work of workers as customer service. Rainbow City employees were part

of the Congress of South African Trade Unions, the countrys labor union

federation, but none of the micro-political contestations documented herein

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

316

Work and Occupations 37(3)

fell within the ambit of the formal process of contract negotiations

and grievance procedures (Wood & Psoulis, 2001). Informally, workers

could and did protest, but they were unable to change any of the policies that

would have afforded them treatment as service professionals. As sociologists, we cannot overlook such symbolic struggles nor dismiss them as

secondary to more material issues. Definitional disputes over service provide

a window into the larger political economy of post-apartheid South Africa.

By treating them as a worthwhile analytical object, we may observe linkages

between macro-level processes (such as new employment equity laws) and

micro-level ones (such as the everyday experience of employees). In short, a

Bourdieuian approach to service work requires that we move from unreflective representations of labor to careful study of labors of representation.

Acknowledgments

For taking the time to provide valuable comments and ideas on this articleand for

inspiring him to finally finish itthe author thanks Katherine Chen, Marek

Korczynski, Robin Leidner, Steve Lopez, Sean ORiain, and Steven Vallas.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship

and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The research on which this article is based was supported by grants from the National

Science Foundation and the Social Science Research Council.

References

Boltanski, L., & Theverot, L. (2006). On justification: Economies of worth. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice. Cambridge, England: Cambridge

University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1979). Algeria 1960. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1990). Homo academicus. Cambridge, England: Polity.

Bourdieu, P. (1993). The field of cultural production: Essays on art and literature.

New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1996). The state nobility: Elite schools in the field of power. Palo Alto,

CA: Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1998a). Acts of resistance: Against the tyranny of the market. New York,

NY: New Press.

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

317

Sallaz

Bourdieu, P. (1998b). Practical reason: On the Theory of Action. Malden, MA: Polity

Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1999a). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1999b). The weight of the world: Social suffering in contemporary society. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2005). The social structures of the economy. Malden, MA: Polity.

Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J.-C. (1979). Reproduction in society, education and culture. London, England: Sage.

Bourdieu, P., & Wacquant, L. (1999). On the cunning of imperialist reason. Theory,

Culture & Society, 16(1), 41-58.

Bowker, G. C., & Star, S. L. (2000). Sorting things out: Classification and its consequences. Boston: MIT Press.

Buhlungu, S. (2009). South Africa: The decline of labor studies and the democratic

transition. Work and Occupations, 36, 145-161.

Dean, D. (2005). Recruiting a self: Women performers and aesthetic labour. Work,

Employment & Society, 19, 761-774.

Desmond, M. (2007). On the fireline: Living and dying with wildland firefighters.

Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Emirbayer, M., & Johnson, V. (2008). Bourdieu and organizational analysis. Theory

and Society, 37(1), 1-44.

Fantasia, R., & Voss, K. (2004). Hard work: Remaking the American Labor Movement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Fligstein, N. (2002). The architecture of markets: An economic sociology of twentyfirst century capitalist societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Goffman, E. (1982). Interaction ritual: Essays on face-to-face behavior. New York,

NY: Pantheon.

Gouldner, A. (1970). The coming crisis of Western sociology. Berkeley: University

of California Press.

Grant, D., Morales, A., & Sallaz, J. J. (2009). Pathways to meaning: A new approach

to studying emotions at work. American Journal of Sociology, 115, 327-364.

Hanser, A. (2008). Service encounters: Class, gender, and the market for social distinction in urban China. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

Hochschild, A. R. (1985). The managed heart: Commercialization of human feeling.

Berkeley: University of California Press.

Hodson, R. (2001). Dignity at work. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Kunda, G. (2006). Engineering culture: Control and commitment in a high-tech corporation. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through

society. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

318

Work and Occupations 37(3)

Leidner, R. (1993). Fast food, fast talk: Service work and the routinization of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lopez, S. H. (2004). Reorganizing the rust belt: An inside study of the American

Labor Movement. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lopez, S. H. (2006). Emotional labor and organized emotional care. Work and Occupations, 33, 133-160.

Macdonald, C. L., & Korczynski, M. (Eds.). (2009). Service work: Critical perspectives. New York, NY: Routledge.

Milkman, R. (2006). L.A. story: Immigrant workers and the future of the U.S. Labor

Movement. New York, NY: Russell Sage Foundation.

Paules, G. (1991). Dishing it out: Power and resistance among waitresses in a New

Jersey restaurant. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

Pettinger, L. (2005). Gendered work meets gendered goods: Selling and service in

clothing retail. Gender, Work & Organization, 12, 460-478.

Podolny, J. M. (2008). Status signals: A sociological study of market signals. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Sallaz, J. J., & Zavisca, J. (2008). From the margins to the mainstream: The unlikely

meeting of Pierre Bourdieu and US sociology. Sociologica, 2, 1-21.

Seidman, G. (2008). Transnational labour campaigns: Can the logic of the market be

turned against itself? Development and Change, 39, 991-1003.

Sherman, R. (2005). Producing the superior self: Strategic comparison and symbolic

boundaries among luxury hotel workers. Ethnography, 6, 131-158.

Sherman, R. (2010). Time is our commodity: Gender and the struggle for occupational legitimacy among personal concierges. Work and Occupations, 37, 81-114.

Smith, V. (1992). Managing in the corporate interest: Control and resistance in an

American bank. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Vallas, S. (2006). Empowerment redux: Structure, agency, and the re-making of managerial authority. American Journal of Sociology, 111, 1677-1717.

Warhurst, C., & Nickson, D. (2007). Employee experience of aesthetic labour in retail

and hospitality. Work, Employment & Society, 21, 103-120.

Webster, E. C. (2002). South Africa. In D. B. Cornfield & R. Hodson (Eds.), Worlds

of work: Building an international sociology of labor (pp. 177-200). New York,

NY: Kluwer Academic.

Webster, E. C., & Omar, R. (2003). Work restructuring in post-apartheid South Africa.

Work and Occupations, 30, 194-213.

Williams, C., & Connell, C. (in press). Looking good and sounding right: Aesthetic

labor and social inequality in the retail industry. Work and Occupations.

Wissinger, E. (2009). Modeling consumption: Fashion modeling work in contemporary society. Journal of Consumer Culture, 9, 273-296.

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

319

Sallaz

Witz, A., Warhurst, C., & Nickson, D. (2003). The labour of aesthetics and the aesthetics of organization. Organization, 10, 33-54.

Wood, G., & Psoulis, C. (2001). Mobilization, internal cohesion, and organized labor:

The case of the Congress of South African Trade Unions. Work and Occupations,

28, 293-314.

Bio

Jeffrey J. Sallaz is an assistant professor of sociology at the University of Arizona.

He is the author of The Labor of Luck: Casino Capitalism in the United States and

South Africa (2009) and is currently researching politics and labor in the global outsourcing field.

Downloaded from wox.sagepub.com by Nicolas Diana on October 25, 2012

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Hollywood Game Plan 20 Page Sample PDFDocument20 pagesHollywood Game Plan 20 Page Sample PDFMichael Wiese Productions0% (1)

- American Woodworker No 171 April-May 2014Document76 pagesAmerican Woodworker No 171 April-May 2014Darius White75% (4)

- Solution of Introduction To Many-Body Quantum Theory in Condensed Matter Physics (H.Bruus & K. Flensberg)Document54 pagesSolution of Introduction To Many-Body Quantum Theory in Condensed Matter Physics (H.Bruus & K. Flensberg)Calamanciuc Mihai MadalinNo ratings yet

- John PFTDocument231 pagesJohn PFTAlexander Santiago ParelNo ratings yet

- The Public Turn - From Labor Process To Labor Movement - BurawoyDocument18 pagesThe Public Turn - From Labor Process To Labor Movement - BurawoyAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Agency Time' - A Case Study of The Postindustrial Timescape and Its Impact On The Domestic SphereDocument23 pagesAgency Time' - A Case Study of The Postindustrial Timescape and Its Impact On The Domestic SphereNicolás DianaNo ratings yet

- Perceptions, Conceptions and Misconceptions of Organized EmploymentDocument7 pagesPerceptions, Conceptions and Misconceptions of Organized EmploymentAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Union presence, class, individual earnings inequalityDocument24 pagesUnion presence, class, individual earnings inequalityAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Youth Representatives' Opinions On Recruiting and Representing Young Workers - A Twofold Unsatisfied DemandDocument17 pagesYouth Representatives' Opinions On Recruiting and Representing Young Workers - A Twofold Unsatisfied DemandAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Cainzos Clase SjuetoDocument19 pagesCainzos Clase SjuetoAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Labor and Climate Policy - A Curriculum For Union Leaders and MembersDocument10 pagesLabor and Climate Policy - A Curriculum For Union Leaders and MembersAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Free-Riding in AustraliaDocument29 pagesFree-Riding in AustraliaAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- How Do Shop Stewards Perceive Their Situation and Tasks - Preconditions For Support of Union WorkDocument32 pagesHow Do Shop Stewards Perceive Their Situation and Tasks - Preconditions For Support of Union WorkAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Brazil - The Swinging Pendulum Between Labor Sociology and Labor MovementDocument15 pagesBrazil - The Swinging Pendulum Between Labor Sociology and Labor MovementAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Global Unions As Imperfect Multilateral Organizations - An International Relations PerspectiveDocument23 pagesGlobal Unions As Imperfect Multilateral Organizations - An International Relations PerspectiveAna MaceoNo ratings yet

- Blue-Collar Public Servants - How Union Membership Influences Public Service MotivationDocument20 pagesBlue-Collar Public Servants - How Union Membership Influences Public Service MotivationAna MaceoNo ratings yet