Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Journal of Technical Writing and Communication-2007-Hartley-95-101

Uploaded by

jana_gavriliuCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Technical Writing and Communication-2007-Hartley-95-101

Uploaded by

jana_gavriliuCopyright:

Available Formats

J. TECHNICAL WRITING AND COMMUNICATION, Vol.

37(1) 95-101, 2007

THERES MORE TO THE TITLE THAN MEETS

THE EYE: EXPLORING THE POSSIBILITIES

JAMES HARTLEY

Keele University, Staffordshire, United Kingdom

ABSTRACT

There is little research on the use of titles in academic articles, and even less

on different types of titles. In this article Crosbys taxonomy of titles [1] is

brought up-to date and extended. Twelve types of titles are distinguished.

The author argues that it would be helpful to discuss these different types

with student writers.

INTRODUCTION

Thirty years ago, Harry Crosby published a treatise on titles [1]. In that paper

he wrote:

I have long believed that the shuttlecock process of finding an appropriate

title stimulates creativity, unity, and significance. The writer starts out with

a working title, writes a few pages, and then pauses to tinker with the title

to make it fit what he has written. This helps him go back to writing with a

sharper focus on what he is really trying to say. This back-and-forth process

continues. If a good title emerges, the writer has evidence that he or she is

developing a significant message expressed in a unified manner. If no title

is possible, something is wrong [1, p. 387].

He continued:

In view of this importance, I have been puzzled by the lack of instruction

available on the subject. Our department library has about 150 feet of shelving

filled with sample writing texts, but the total information comes to something

like this: Center your title on the first page three spaces above your theme.

Capitalize initial letter except for short prepositions. Your title should

announce your subject matter and catch attention [1, p. 387].

95

2007, Baywood Publishing Co., Inc.

96 / HARTLEY

This picture has not changed much since 1976, although some modern texts do

contain more advice on writing titles (e.g., [2-4]). There are also more research

papers available on the topic (e.g., [5-10]). Nonetheless, most texts on academic

writing scarcely mention writing the title, which is surprising given that it is the

title that: i) attracts a reader to a paper in the first place; and ii) is of considerable

importance in computer-based literature searches (see [11, 12]).

In his paper, Crosby analyzed the forms and function of over 300 titles (in

the humanities) with a view to seeing if he could create a taxonomy of titles.

His aim was to let his students see and judge for themselves the effectiveness

of different types of titles so that they would be better informed when they came

to writing their own.

Crosby distinguished between four main types of titles and several subtypesand gave examples of each kind. In this article, I distinguish between

12 kinds of titles, eight of which appeared in Crosbys paper. My examples for

each kind are drawn mainly from papers in the field of educational psychology.

TWELVE TYPES OF TITLE

The twelve types of titles that I find it useful to distinguish between are as

follows:

1. Titles that announce the general subject: for example:

The age of adolescence

Designing instructional and informational text

On writing scientific articles in English

Crosby noted that such titles were sufficient when they were used by wellknown authors, but that novices using such titles had not yet learned that

they needed informative and provocative titles [1, p. 387].

2. Titles that particularize a specific theme following a general heading:

for example:

Pre-writing: The relation between thinking and feeling

The achievement of black Caribbean girls: Good practice in Lambeth schools

The role of values in educational research: The case for reflexivity

Here these examples all use a colon to facilitate the particularization, but this

is not always necessary. However, as Crosby acknowledges, colons are helpful in

this respect. (For a further discussion of colons, see [7].)

3. Titles that indicate the controlling question: for example:

Is academic writing masculine?

What is evidence-based practiceand do we want it too?

What price presentation? The effects of typographic variables on essay grades

These titles indicate what the argument of the paper is about, but they do

not provide a clear answer to this question at this stagealthough this might be

implied from the way that the question is framed. The next set of titles is clearer

in this respect.

THE USE OF TITLES IN ACADEMIA /

97

4. Titles than indicate that the answer to a question will be revealed: for

example:

Abstracts, introductions, and discussions: How far do they differ in style?

The effects of summaries on the recall of information

Current findings from research on structured abstracts

Curiously enough there are disciplinary differences in the use of questions in the

titles of research articles. According to Hyland [13], scientists hardly ever use

them, whereas, in my experience, they are slightly more common in educational

and social science research journals and conference papersup to 10% [7].

According to Crosby, the next set of titles announce the thesiswhich I take

to mean the authorsposition on the topic in question. These are:

5. Titles that indicate the direction of the authors argument: for example:

The lost art of conversation

Plus ca change . . . Gender preferences for academic disciplines

Down with op. cit.

The sixth type of title does not appear in Crosbys list. This may be a function of

different disciplines. In this set of titles, the research methods used are given

particular salience.

6. Titles that emphasize the methodology used in the research: for example:

Using colons in titles: A meta-analytic review

Reading and writing book reviews across the disciplines: A survey of authors

Is judging text on screen different from judging text in print? A naturalistic

e-mail study

This feature most commonly occurs in medical research journals. Since

2003, for example, the British Medical Journal has required all of the titles of

their published research papers to end (after a colon) with a statement about the

method used.

Other sets of titles that also seem quite common, not mentioned by Crosby, are

titles that suggest guidelines, or comparisons.

7. Titles that suggest guidelines and/or comparisons: for example:

Seven types of ambiguity

Nineteen ways to have a viva

Eighty ways of improving instructional text

Finally, Crosby distinguishes between various forms of title under the umbrella

heading of titles that bid for attention. Here I have subdivided these into separate

groupsalthough there are overlaps and combinationsas follows:

8. Titles that bid for attention by using startling or effective openings: for

example:

Do you ride an elephant and never tell them youre German: The experiences of British Asian, black, and overseas student teachers in the UK

98 / HARTLEY

Something more to tell you: Gay, lesbian, and bisexual young peoples

experiences of secondary schooling

Making a difference: An exploration of leadership roles in sixth form colleges

9. Titles that attract by alliteration: for example:

A taxonomy of titles

Legal ease and legalese

Referees are not always right: The case of the 3-D graph

10. Titles that attract by using literary or biblical allusions: for example:

From structured abstracts to structured articles: A modest proposal

Low! They came to pass. The motivations of failing students.

Lifting the veil on the viva: The experiences of postgraduate students

11. Titles that attract by using puns: for example:

Now take this PIL (Patient Information Leaflet)

A thorn in the Flesch: Observations on the unreliability of computer-based

readability formulae (Rudolph Flesch devised a method of computing the

readability of text)

Unjustified experiments in typographical research and instructional design

(text set with equal word-spacing and a ragged right-hand edge is said to be set

unjustified: text set with variable word-spacing and a straight right-hand

edge is set justified).

Crosby warned his readers about using literary or biblical allusions. As he

put it, In a time when students have read so little, a literary allusion is often an

illusion [1, p. 390]. We might possibly say the same about puns, since I have

had to explain the ones above.

And finally:

12. Titles that mystify: for example:

Outside the whale

How do you know youve alternated?

Is October Brown Chinese?

Titles that mystify may attract the indulgent reader but they are hardly likely

to help busy ones [14]. Outside the whale refers to the fact that the author

is describing a typographic design course that was run for over 20 years

independently of, and not swallowed up by, the requirements of Fine Arts

schools in the United Kingdom. How do you know youve alternated? is about

problems that sociologists have when alternating between presenting an accurate

description of the groups they study and presenting their interpretation to the

readers. October Brown turns out to be the name of a teacher.

Irony, humor, and cultural references are difficult for non-native speakers of

the language to understand. They should probably be avoided in the titles of

academic articles.

THE USE OF TITLES IN ACADEMIA /

99

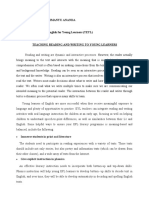

Table 1. Titles Used by Students (Left Column) for Their Projects

and the Authors Revised Versions (Right Column)

Approach to study. (Chinese

student)

Gender and nationality differences in

approaches to study: Findings from

English and Chinese Business Studies

students.

Perceptions of psychology

university students.

Do psychology students perceptions of

Psychology change over time?

An investigation into mature

students, revision styles, and

examination performance.

Revision styles and examination

performance in mature and

traditional-entry students.

Possible gender and year of study

differences in the orientation of

students learning strategies.

Students learning strategies: the effects of

gender and year of study.

Parenting styles and academic

achievement.

Do differences in early parenting styles

affect the academic achievement of men

and women undergraduates?

University students estimations

of occupational intelligence

versus gender.

How intelligent do you need to be to be

a surgeon? Male and female students

estimates of the intelligence required to

carry out male, female, and gender-neutral

occupations.

The effect of term-time employment on final year university

students.

The effects of term-time employment upon

the academic performance of final-year

university students.

Student preferences of class

size in higher education.

Class size matters! The preferences of

undergraduates.

Students experiences of studying

Psychology at degree level: Is

there a difference between those

that have previously studied the

subject at A-level and those who

have not.

How far does studying Psychology at

A-level impact upon the experiences and

performance of Psychology students at

university?

100 / HARTLEY

CONCLUDING COMMENTS

In this article I have tried to bring Crosbys treatise on titles up-to-date, and to

cast it in a social science context. I want suggest, like Crosby, that tutors could

profitably discuss such a list with their students to help them to reflect on what

kind of title is appropriate for their particular texts. This article moves, therefore,

beyond a detailed discussion of the use of features like colons or question marks

in titles to focus more on the particular functions of different types of title.

Table 1 illustrates why I think that it would be helpful to discuss such functions

with undergraduate (and postgraduate) students. This table shows, for example,

the original titles proposed by eight of my recent final-year psychology students

for their projects, followed by what I hope are more informative titles based on my

suggestions. Most of these changes expand and clarify the originals. Readers

may judge for themselves whether or not they think there is an improvement.

REFERENCES

1. H. H. Crosby, Titles, A Treatise On . . . , College Composition & Communication, 27:4,

pp. 387-391, 1976.

2. R. Day and B. Gastel, How to Write and Publish a Scientific Paper (6th Edition),

Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2006.

3. M. Forshaw, Your Undergraduate Psychology Project: A BPS Guide, Blackwell,

London, 2004.

4. J. M. Swales and C. B. Feak, Academic Writing for Graduate Students (2nd Edition),

University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, 2006.

5. L. Anthony, Characteristic Features of Research Article Titles in Computer Science,

I.E.E.E. Transactions on Professional Communication, 44:3, pp. 187-194, 2001.

6. M. Haggan, Research Paper Titles in Literature, Linguistics and Science: Dimensions

of Attraction, Journal of Pragmatics, 36, pp. 293-317, 2004.

7. J. Hartley, Planning that Title: Practices and Preferences for Titles with Colons. (Paper

submitted for publication: copies available from the author.)

8. T. D. C. Kutch, Relation of Title Length to Numbers of Authors in Journal Articles,

Journal of the American Society for Information Science, 19:4, pp. 200-202, 1978.

9. C. Whissell, Titles of Articles Published in the Journal of Psychological Reports:

Changes in Language, Emotion and Imagery Over Time, Psychological Reports, 94,

pp. 807-813, 2004.

10. M. Yitzhaki, Relation of Title Length of Journal Articles to Number of Authors,

Scientometrics, 30, pp. 321-332, 1994.

11. M. A. Mabe and M. Amin, Dr. Jeckyll and Dr. Hyde: Author-Related Assymetries

in Scholarly Publishing, Aslib Proceedings, 54:3, pp. 149-157, 2002.

12. A. Tombros, l. Ruthven, and J. M. Jose, How Users Assess Web Pages For Information

Seeking, Journal the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 56:4,

pp. 327-344, 2005.

13. K. Hyland, What Do They Mean? Questions in Academic Writing, Text, 22:4,

pp. 529-557, 2002.

THE USE OF TITLES IN ACADEMIA /

101

14. J. Hartley, To Attract or To Inform: What Are Titles For? Journal of Technical Writing

and Communication, 32:2, pp. 203-213, 2005.

Other Articles On Communication By This Author

Hartley, J., Reading and Writing Book Reviews Across the Disciplines, Journal of the

American Society for Information Science and Technology, 57:9, pp. 1194-1207.

Hartley, J., Is Academic Writing Masculine? Higher Education Review, 37:2, pp. 53-62,

2005.

Hartley, J., Designing Instructional and Informational Text, in Handbook of Research in

Educational Communications and Technology (2nd Edition), D. H. Jonassen (ed.),

Erlbaum, Mahwah, New Jersey, pp. 917-947, 2004.

Hartley, J., Current Findings from Research on Structured Abstracts, Journal of the

Medical Library Association, 92:3, pp. 368-371, 2004.

Hartley, J., E. Sotto, and C. Fox, Clarity Across the Disciplines: An Analysis of Texts in the

Sciences, Social Sciences, and Arts and Humanities, Science Communication, 26:2,

pp. 188-210, 2004.

Hartley, J. and R. N. Kostoff, How Useful Are Key Words in Scientific Journals? Journal

of Information Science, 29:5, pp. 433-438, 2003.

Hartley, J., J. W. Pennebaker, and C. Fox, Abstracts, Introductions and Discussions:

How Far Do They Differ in Style? Scientometrics, 57:3, pp. 389-398, 2003.

Hartley, J., E. Sotto, and J. W. Pennebaker, Style and Substance in Psychology: Are

Influential Articles More Readable Than Less Influential Ones? Social Studies of

Science, 32:2, pp. 321-334, 2002.

Hartley, J., M. J. A. Howe, and W. J. McKeachie, Writing Through Time: Longitudinal

Studies of the Effects of New Technology on Writing, British Journal of Educational

Technology, 32:2, pp. 141-151, 2001.

Hartley, J., What Do We Know About Footnotes? Opinions and Data, Journal of

Information Science, 25:3, pp. 205-212, 1999.

Direct reprint requests to:

Prof. James Hartley

School of Psychology

Keele University

Staffordshire

ST5 5BG

UK

e-mail: j.hartley@psy.keele.ac.uk

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Chapter 21 - Pitched RoofingDocument69 pagesChapter 21 - Pitched Roofingsharma SoniaNo ratings yet

- David Edmonds, Nigel Warburton-Philosophy Bites-Oxford University Press, USA (2010) PDFDocument269 pagesDavid Edmonds, Nigel Warburton-Philosophy Bites-Oxford University Press, USA (2010) PDFcarlos cammarano diaz sanz100% (5)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- 2019 Brief History and Nature of DanceDocument21 pages2019 Brief History and Nature of DanceJovi Parani75% (4)

- Bicol Merchant Marine College Inc. Rizal Ave. Piot, Sorsogon City EmailDocument2 pagesBicol Merchant Marine College Inc. Rizal Ave. Piot, Sorsogon City EmailPaulo Generalo100% (1)

- Cartooning Unit Plan Grade 9Document12 pagesCartooning Unit Plan Grade 9api-242221534No ratings yet

- Acr Portfolio DayDocument4 pagesAcr Portfolio DayNica Salentes100% (2)

- Director Capital Project Management in Atlanta GA Resume Samuel DonovanDocument3 pagesDirector Capital Project Management in Atlanta GA Resume Samuel DonovanSamuelDonovanNo ratings yet

- Letter Re OrientationDocument7 pagesLetter Re OrientationJona Addatu0% (1)

- Nine Steps From Idea To Story 5Document43 pagesNine Steps From Idea To Story 5Jom Jean100% (1)

- ABM - AOM11 Ia B 1Document3 pagesABM - AOM11 Ia B 1Jarven Saguin50% (6)

- Jamali TitleDocument10 pagesJamali Titlejana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- IBRAHIM TAHA The Power of The TitleDocument18 pagesIBRAHIM TAHA The Power of The Titlejana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- Naghib Lahlou The Poetics of TitleDocument18 pagesNaghib Lahlou The Poetics of Titlejana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- Salager - Angeles Titles Are Serious StuffDocument15 pagesSalager - Angeles Titles Are Serious Stuffjana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- Soler Writing Titles in Science2007Document13 pagesSoler Writing Titles in Science2007jana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- Goodman What S in A TitleDocument4 pagesGoodman What S in A Titlejana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- Exploring the Multiple Voices and Identities of Mature Multilingual WritersDocument24 pagesExploring the Multiple Voices and Identities of Mature Multilingual Writersjana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- Haggan Research Paper Titles in Lit 2004Document25 pagesHaggan Research Paper Titles in Lit 2004jana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- Buxton The Variation of Information in Titles1977Document7 pagesBuxton The Variation of Information in Titles1977jana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- Gesuato Encoding of Information in TitlesDocument31 pagesGesuato Encoding of Information in Titlesjana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- On Alternative ModernitiesDocument18 pagesOn Alternative Modernitiesjana_gavriliuNo ratings yet

- RESUMEDocument2 pagesRESUMERyan Jay MaataNo ratings yet

- Grade Sheet For Grade 10-ADocument2 pagesGrade Sheet For Grade 10-AEarl Bryant AbonitallaNo ratings yet

- Geotechnical Engineering 465Document9 pagesGeotechnical Engineering 465Suman SahaNo ratings yet

- Name: Fajar Abimanyu Ananda NIM: I2J022009 Class: Teaching English For Young Learners (TEYL)Document3 pagesName: Fajar Abimanyu Ananda NIM: I2J022009 Class: Teaching English For Young Learners (TEYL)Fajar Abimanyu ANo ratings yet

- Acharya Institute Study Tour ReportDocument5 pagesAcharya Institute Study Tour ReportJoel PhilipNo ratings yet

- Indian Rupee SymbolDocument9 pagesIndian Rupee SymboljaihanumaninfotechNo ratings yet

- GA2-W8-S12-R2 RevisedDocument4 pagesGA2-W8-S12-R2 RevisedBina IzzatiyaNo ratings yet

- Activity.2 21st Century EducationDocument7 pagesActivity.2 21st Century EducationGARCIA EmilyNo ratings yet

- What Does Rhythm Do in Music?: Seth Hampton Learning-Focused Toolbox Seth Hampton February 16, 2011 ETDocument2 pagesWhat Does Rhythm Do in Music?: Seth Hampton Learning-Focused Toolbox Seth Hampton February 16, 2011 ETsethhamptonNo ratings yet

- Movements of Thought in The Nineteenth Century - George Herbert Mead (1936)Document572 pagesMovements of Thought in The Nineteenth Century - George Herbert Mead (1936)WaterwindNo ratings yet

- Emmanuel 101Document7 pagesEmmanuel 101Khen FelicidarioNo ratings yet

- CV Julian Cardenas 170612 EnglishDocument21 pagesCV Julian Cardenas 170612 Englishjulian.cardenasNo ratings yet

- Review Yasheng-Huang Capitalism With Chinese Characteristics Reply NLRDocument5 pagesReview Yasheng-Huang Capitalism With Chinese Characteristics Reply NLRVaishnaviNo ratings yet

- 5 Point Rubric Condensed-2Document2 pages5 Point Rubric Condensed-2api-217136609No ratings yet

- Integrated Speaking Section Question 3Document14 pagesIntegrated Speaking Section Question 3manojNo ratings yet

- Ghotki Matric Result 2012 Sukkur BoardDocument25 pagesGhotki Matric Result 2012 Sukkur BoardShahbaz AliNo ratings yet

- NORMAL DISTRIBUTION (Word Problem)Document9 pagesNORMAL DISTRIBUTION (Word Problem)Carl Jeremie LingatNo ratings yet

- NAVMC 3500.89B Ammunition Technician Officer T-R ManualDocument48 pagesNAVMC 3500.89B Ammunition Technician Officer T-R ManualtaylorNo ratings yet

- The National Law Institute University: Kerwa Dam Road, BhopalDocument2 pagesThe National Law Institute University: Kerwa Dam Road, Bhopaladarsh singhNo ratings yet

- Zambia Weekly - Week 38, Volume 1, 24 September 2010Document7 pagesZambia Weekly - Week 38, Volume 1, 24 September 2010Chola MukangaNo ratings yet