Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1.jet Airways Case

Uploaded by

Monish AgrawalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1.jet Airways Case

Uploaded by

Monish AgrawalCopyright:

Available Formats

1

CASE 1

Jet Airways (I) Ltd. (plaintiff)

vs

Mr. Jan Peter Ravi Karnik (defendant)

This case is being discussed in the back drop of legality of object of a contract. Even though the

contract law proposes freedom of parties to enter into a contract, still it is subject to certain

rules especially with regards to the subject matter of the contract. The case describes the

different aspects of an employment contract, especially the validity and enforceability of a noncompete clause which is often used by companies.

Reference: The given concepts have been discussed from page 67 74 of the prescribed text.

(Certain irrelevant parts of the case have been deleted for ease of understanding)

The Plaintiffs prayer before the court

The plaintiff seeks an order of permanent injunction 1 restraining the defendant from taking;

up or continuing any employment until 11th October, 2005 with any other Airline, including

Sahara Airlines for the purpose of operating aircraft on the basis of the endorsement of the

licence obtained as a result of the training provided by the plaintiff, that is to say, for

operating B 737 Series 300/400/500.

The plaintiff also seeks money, decree against the defendants for the return of the training

cost incurred together with interest at the rate of 24 per cent per annum.

Facts of the case

The plaintiff carries on the business of Air transport carrier within India and operates a fleet of

modern Aircraft. The plaintiff commenced operation in May, 1993. It decided to operate and

expand its fleet based on the latest series of Boeing 737 aircraft in India only the Aircraft 737200 was operated. The plaintiff, however, introduced the series B 737-300/400. The plaintiff was

the first Airline to induct these two series of aircrafts in India. When the plaintiff commenced

1 A final order of a court that a person or entity refrain from certain activities

permanently or take certain action (usually to correct a nuisance). A permanent

injunction is distinguished from a "preliminary" injunction which the court issues

pending the outcome of a lawsuit or petition asking for the "permanent" injunction.

operations, there were no pilots in India who were rated for this type of aircraft i.e. who were

valid licences endorsed by the Director General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) to fly this type of

aircraft. The plaintiff, therefore, embarked on a manpower plan of recruiting Indian pilots and

training in the First Officers and Commanders. In the initial year of the Airlines operation, the

Aircraft were commanded by foreign instructors who were training the plaintiff Indian Pilots.

The defendant was employed by the Plaintiff after an interview on 30th April, 1998. Prior to

joining the plaintiff, the defendant was employed by the Indian Navy and thereafter by Span Air.

When the defendant joined the plaintiff, he had been flying Super King Air 8 200". In order to

equip the pilots for operating B-737/300/400 series an intensive training has to be undertaken.

The plaintiff organised the necessary training for the defendant and the other pilots. In the letter

of appointment dated 30th April, 1998 the defendant was offered the post of Trainee First Officer

on certain terms and conditions. In consideration of the plaintiff making the arrangement for the

training of the defendant, the defendant agreed and undertook that during a period of 7 years

from the date of completion of training in India and abroad and on resuming actual services with

the plaintiff as First Officer, he would not accept employment, similar in nature, either in full

time or part time with any other employer. In the event of the defendant resigning from the

services, he would make good to the plaintiff entire cost in respect of training and/or damage, if

any.

The defendant joined the services of the plaintiff w.e.f. 4th May, 1998. The total cost of training

is approximately Rs. 15 lakhs. All the conditions were satisfied by the defendant and he was sent

for training to Malaysia between 11th May, 1998 and 11th June, 1998 and between 15th August,

1998 and 5th September, 1998. The plaintiff incurred an amount of Rs. 11,31,400 on the training

of the defendant. On the basis of the training, the defendant obtained B-737-300/400/500, P2

endorsement with effect from 12th October, 1998. The defendant was confirmed in service of the

plaintiff on 6th February, 1999. By letter dated 4th December, 1999, the defendant resigned from

the services of the plaintiff with immediate effect. The reason stated for resignation was the

adverse changes to the rule of seniority. On 27th December, 1999 the defendant was informed

that he had wrongfully abandoned the services of the plaintiff in breach of the terms of

employment and, therefore, necessary legal steps will be instituted against him.

The relevant terms and conditions of the appointment as given in the letter dated 30th April,

1998 are as under.

Clause 1. You shall be in possession of valid Indian ALTP/IR/FRTQ/RTR/Licence.

Clause 3. You will be initially on training for which the company will make necessary

arrangements. You will have to pass the company's technical/performance examination

and the DGCA Technical Examination for B-737-300/400 endorsement within two

attempts, failing which your training will stand automatically terminated.

You will have to complete successfully simulator and flying training and obtain B- 737300/400 endorsement, should you fail to obtain the same within company's stipulated

time, your training shall stand terminated.

Details of the training will be intimated to-you separately. On successful completion of

your training including Simulator and Flying training and on obtaining B-737-300/400

endorsement you shall be on probation.

Clause 6.

The total cost of your training is estimated at approximately Rs. 15.0 lakhs

(Rupees Fifteen Lakhs only) which you are required to pay back to the company.

Refundable Demand Draft- to be retained for 7 years without interest 2.5 Lakhs

EMI of minimum of 33,000/- to be payable at Rs. 1,500/- per day to be recovered

from salary over 24 months (This amount will not be refunded in the event of

failure to complete simulator/ground classes and the company finds performance

during the training to be below acceptable standards). 33,000/- is based on 22

days of minimum flying and on and additional flying done Company will adjust a

further sum @ Rs. 1,500/- per flight day

Indemnity bond with 2 sureties for Rs 7.5 lakhs for a period of 7 years during

which he shall not leave or terminate his services

Clause 21. You will be required to serve the company for a minimum period of 7 years

from the date of your obtaining B-737-300/400 endorsement on your flying licence. In the

event of your resigning/leaving the service before the completion of the period aforesaid

for any reason whatsoever, you shall make good and pay to the company the entire cost

in respect of training and/or damages, if any.

Clause 22. During this period of seven years, you shall be exclusively employed by Jet

Airways and perform your duties towards Jet Airways. You shall agree that during the

said period of seven years you shall not take up employment with any other

persons/organisations/companies requiring you to perform similar duties as required to

be performed by Jet Airways and shall not engage in any similar business or vocation

requiring you to fly any other Aircraft.

Clause 23. After confirmation, the company would be entitled to terminate your services

without assigning any reason, by giving you three months notice in writing or by payment

of three months salary in lieu of such notice. In the event of your desiring to leave the

services of the company at any time after confirmation, you shall give to the company

three months notice in writing provided that the company may, at its sole discretion,

waive such notice. This is subject to provisions of para No. 20."

During this period of 7 years you shall not accept employment, similar in nature, either

full time or part time with any other employer. This period of 7 years shall be computed

from the period of the completion of the above said training in India and abroad and on

resuming actual services with the employer company as a First Officer."

Arguments on behalf of the Plaintiff

Mr. Vahanavati, learned Counsel for the plaintiff, submits that on reading of Clause 6 it clearly

show that the defendant had agreed to serve the company for a period of 7 years and not to leave

or terminate his services till the expiration of the period of 7 years. The defendant had also

agreed not to accept employment similar in nature either full time or part time with any other

employer during the period of 7 years. This negative covenant is reiterated by the defendant on

23rd September, 1998 whilst executing the bond. Apart from this, there is a complete negative

covenant contained in Clause 22. There is no option given to the defendant to cut short the period

of 7 years. It is submitted that the plaintiff has spent large amounts of money on training the

defendant. He cannot now be permitted to facilitate the competitor in getting unfair and

dishonest advantage against the plaintiff. It is, therefore, absolutely necessary that the injunction

be granted. Learned Counsel submitted that grave and irreparable loss and damage will be

caused to the plaintiff and the breach cannot be compensated in terms of money. He submitted

since 8 pilots have left the services of the plaintiff one after the other and joined Sahara Airlines,

it has led to disruption of the plaintiffs schedule. The difficulties experienced by the plaintiff

cannot be compensated in terms of money.

Learned Counsel has relied on two judgments of the Supreme Court to submit that in the

case of a clear negative covenant the relief of injunction can be granted, restricted of course to

the period of contract. Indeed all the learned Counsel on both the sides have relied on the same

judgments. These are (i) M/s. Gujarat Bottling Co. Ltd. v. Coca Cola Company and others, ,

hereinafter referred to as "the Coca Cola case" and (II) Niranjan Shankar Golikari v. Century

Spinning and Mfq. Com. Ltd., , hereinafter referred to as "the Golikari" case.

Mr. Chagla, learned Counsel also appearing for the Plaintiff has submitted that the negative

covenant contained in Clauses 6 and 22 are not in restraint of trade. The breach of the contract is

clear. In terms of Clause 6, an enormous amount of money has been spent on the training of the

defendant. The covenant contained in Clauses 6, 21 and 22 are affirmative as well as negative in

nature. He submits that the excuse given for leaving the company is an afterthought. This is a

clear case of illegal inducement being offered by Sahara Airlines. The plaintiffs are perfectly

within their right in accordance with the contract to rationalise the criteria for fixation of

seniority. The excuse put forward by the defendant is baseless and misconceived and has been

made only as a prelude to justify the breach of the contract. The seniority list was in fact duly

published in July, 1999. The objections were invited and they have been dealt with. He submitted

that if in a matter of this nature, the defendants are successful in resisting an injunction, it would

mean that there is no sanctity of contract. Learned Counsel submits that the sanctity of contract

must be enforced by the courts on the principles of equity and good conscience. Otherwise it

would lead to inducements being offered by the competitors. This has happened quite blatantly in

the present case. Eight pilots of the plaintiff have left and joined the competitor giving only lame

excuses for the breach of the contract.

Learned Counsel submits that it will be in the public interest to enforce the contract by way of

injunction. If this is not done, it would send a totally wrong signal in the Airline industry. The

Airlines will cut corners in training the pilots. This may lead the Airlines to curtailing the extent

of training as the Airlines would not know as to how long the pilot that has been trained by them

is likely to serve them.

Learned Counsel readily agrees that so far as law in India is concerned, there can be no

injunction on the basis of a negative covenant in the post contract period. This would be void

under section 27 of the Contract Act. However, during the period of contract injunction can and

should be granted. He submits that balance of convenience is clearly in favour of the plaintiff. If

these pilots are permitted to join Sahara Airlines it would cause irreparable loss. On the other

hand, if the injunction is issued, the defendant would not remain idle. He would still be entitled

to fly other kinds of planes. It may be that he would get a lesser salary but this would not be

sufficient to prevent the Court from granting the injunction sought. The learned Counsel had very

fairly stated that there is a judgment of this Court given by Lodha, J., in the case of Harjit Singh

Kang v. Jet Airways (India) Put. Ltd., decided on 24th July, 1996 which would need to be

distinguished. In that case the plaintiffs had filed a suit in the City Civil Court seeking an

injunction on the basis of an implied negative covenant. There was no express negative covenant

like in the present case. The City Civil Court had granted an injunction. According to the learned

Counsel, in the present case the injunction is restricted only to B-737-300/400 series. Therefore,

the observation made by Lodha, J., would not be applicable to the facts and circumstances of this

case. Furthermore, Lodha, J., has refused to grant the injunction on the basis of the finding that

there is no implied negative covenant. The negative covenant has been specifically provided in

all the letters of appointment and in the indemnity bonds in view of the judgment of Lodha, J.

The defendant in this case has agreed to exclusively work for the plaintiff for a period of 7 years.

Thus he cannot now be permitted to work with any other Airline in India on B-737-300/400

series Aeroplanes.

Mr. Dwarkadas, learned Counsel appearing in Notice of Motion Nos. 633 and 634 of 2000 has

made some additional submissions. In Suit No. 712 of 2000 the defendant had been appointed on

9th May, 1996; According to the learned Counsel, after the judgment of Lodha, J., the defendant

executed a bond sometime in the year 1997 which contain an express negative covenant. This,

according to the learned Counsel, was a complete negative covenant and there is no option left

with the employee. The resignation of the defendant was given on 6th December, 1999, only one

day before joining the Sahara Airlines. Distinguishing the judgment of Lodha, J., the learned

Counsel submitted that a perusal of the judgment would show that if the Court had come to the

conclusion that there was an implied negative covenant then the injunction would have followed.

It is only because the Court came to the conclusion that no negative covenant can be implied that

the injunction was refused.

Furthermore, the learned Counsel submitted that injunction in similar circumstances had been

given by the Supreme Court in Golikari's case (supra). In that case there was a similar

affirmative covenant as well as the negative covenant. In that case negative covenant had

provided for an obligation to serve the company. Liquidated damages were provided in case of

breach of contract and the negative covenant not to engage or carry on the business being carried

on by the company. He was also not to serve in any capacity for any other company carrying on

similar business. Learned Counsel has reiterated that the plaintiffs are not seeking any restraint

against the defendant in the post contract period.

The plaintiff is only seeking an injunction during the period of the contract. Learned Counsel has

also relied on the observations of the Supreme Court in para 34 of the Coca Cola case. In this it

is reiterated that except in cases where the contract is wholly one sided, normally the doctrine of

restraint of trade is not attracted in cases where the restriction is to operate during the period the

contract is subsisting and it applies in respect of a restriction which operates after the termination

of the contract.

Arguments on behalf of the Defendant

Mr. Tulzapurkar, learned Counsel appearing for the defendant has argued that the negative

covenant is too wide. It is not restricted in any manner. The Supreme Court in Golikari's case has

clearly held that merely because there is a negative covenant does not necessarily mean that the

Court has to grant the injunction.

Independently of this, Mr. Tulzapurkar submits that in view of the parties having themselves

contemplated either the plaintiff dismissing the defendant or the defendant leaving the services of

the plaintiff, under section 41(h) of the Specific Relief Act 2, no injunction should be granted. The

plaintiffs have themselves provided an equally efficacious remedy by way of liquidated damages.

He further submits that the negative covenant cannot be enforced after the contract has been

terminated. He further submits that no public interest whatsoever is involved for granting the

injunction to the plaintiff. In fact, it would be positively against the public interest to compel a

disgruntled pilot to work for an employer for whom he does not wish to work. The defendant has

left the plaintiff because of the change in the conditions of service of the defendant. Promotions

have been denied to the defendant. His seniority has been adversely affected. He submitted that

in para 12 of the affidavit in reply, detailed reasons as to why the defendant was compelled to

leave the services of the plaintiff has been' set out. One of the reasons was that the defendant was

entitled to Rs. 1,500/- per day as flight duty allowance. This was unceremoniously reduced by

the plaintiff to Rs. 500/- per day. Thus the defendant was caused a loss of Rs. 2,20,000/-. On the

2 Section 41: Injunction when refused.An injunction cannot be granted(h) when equally

efficacious relief can certainly be obtained by any other usual mode of proceeding except in

case of breach of trust;

representation of the defendant, the V.P. operations has ruled for the payment of the allowance to

the defendant and had directed the personal section to pay the arrears at the rate of Rs. 1,500/per day. According to the learned Counsel, this point is deliberately not dealt with by the

plaintiff. This itself is sufficient to reject the claim of the plaintiff for any discretionary relief.

The plaintiffs themselves having committed wrongs cannot rely on the same to seek an

injunction.

Learned Counsel further submitted that granting of injunction in these circumstances would

render the defendant wholly idle. He is specially trained to fly the B-737/300/400 series

Aeroplane. There is only one other scheduled Airline in India viz. Sahara Airlines in which these

planes are available. Thus if the defendant is not permitted to work with Sahara Airlines, the

injunction would amount to forcing the defendant to work again with the plaintiff. This would be

specific performance of a contract of personal service which relief cannot be granted by virtue of

section 14 of the Specific Relief Act.

Mr. Naphade, learned Counsel has adopted the argument of Mr. Tulzapurkar. He has, however,

made certain additional points which may be noticed. Learned Counsel submits that a perusal of

Clause 6 of the letter of appointment shows that the training is only financed by the defendant as

a loan transaction. Therefore, the training has been received by the defendant at his own expense.

Thus the plaintiff has no proprietary rights in the intellectual property rights which flow from the

training. These intellectual property rights are vested in the defendant. Therefore no injunction

can be granted which would prevent the defendant from exercising his proprietary rights. The

plaintiff has only advanced a loan. To secure the repayment of the loan the plaintiff has taken a

guarantee in the amount of Rs. 7.5 lakhs for 7 years. Rest of the amount was being deducted

from the salary of the defendant as provided in Clause 7. Learned Counsel further submits that

Clause 6 if read in conjunction with Clauses 21 and 22 would show that there is no negative

covenant. Clause 21 is equivalent to Clauses 1 and 13 which had been construed by Lodha, J.

Therefore, the plaintiff has now added Clause 22. Clause 22 is clearly in conflict with Clauses 6

and 21. The whole document has to be construed harmoniously. Clause 22 cannot be construed in

isolation to cull out a negative covenant. Learned Counsel further submits that 7 years mentioned

in Clauses 6, 21 and 22 would mean 7 years during the employment of the defendant with the

plaintiff. This Clause cannot mean that even if there is a breach of contract by the plaintiff which

compels the defendant to leave the services of the plaintiff, the defendant would be bound not to

accept any other assignment till the expiry of 7 years. The plaintiffs cannot be permitted to take

advantage of their own wrong. Once the employment is terminated either by the plaintiff or by

the defendant, then any further restriction would be violative of section 27 of the Contract Act.

Learned Counsel submits that Clause 22 has to be read down to mean that there would be no

restriction of 7 years if the contract comes to an end before the period of 7 years. Learned

Counsel also relies on sections 73 and 74 of the Contract Act to submit that liquidated damages

having been stipulated in Clause 6 would disentitle the plaintiff from the relief of injunction.

Learned Counsel further submits that there is no public interest involved. In fact pleadings

categorically show that the suit is filed merely for recovery of damages. Learned Counsel has

referred to page 26 of the plaint wherein it is categorically stated as follows:

"..... The whole purpose of the said negative covenant is to ensure that such pilots in whom the

plaintiff made such tremendous investment are not lured away by a competitor in breach of their

contracts. The plaintiff was the first airline in the country to conceive and implement the policy

of modernising its fleet inducted the latest version of the 737 Boeing aircraft in the country.

Sahara Airlines followed suit much later and is now trying to take dishonest advantage with the

plaintiffs trained pilots. The effect of the pilots leaving the plaintiff not only disrupts the

plaintiffs programming but also represents a considerable set back to the plaintiff in its

operation."

A perusal of the above, according to the learned Counsel shows that the plaintiff is only

interested in protecting the tremendous investment made by the plaintiff in the training of the

defendant. This, according to the learned Counsel, can be sufficiently compensated by damages.

Thus, there is no public interest but only commercial interest. Learned Counsel further submits

that injunction cannot be granted in view of section 41(e) and section 42 of the Specific Relief

Act. Section 41(e) provides that there can be no injunction in cases where specific performance

of the contract cannot be ordered- Section 42 provides that in order to get the relief of injunction

the plaintiff must perform the obligations under the contract. In the present case, if the injunction

is granted it would be in violation of section 41(e) of the Specific Relief Act. Learned Counsel

submits that if an injunction is granted not only the defendant will be left idle but his career

would be ruined. After six months of no flying the licence of the defendant is liable to be

cancelled. Thereafter the fresh training would have to be undergone. Therefore, this is a pressure

tactic to compel the defendant to specifically perform the contract of personal service.

As far as balance of convenience is concerned, learned Counsel submits that the defendant will

lose his job in Sahara. He will sit idle and he will lose his licence. The object of the injunction is

to protect the plaintiff against any possible injury which cannot be compensated by way of

damages. Thus the balance of convenience clearly lies in favour of the defendant. The question

10

as to how the discretion is to be used has been clearly laid down by Lodha, J. If the injunction is

granted it would amount to granting an order of mandatory injunction3. This kind of an order can

only be made after the trial of the suit. In Golikari's case (supra) the injunction was granted after

the trial.

Learned Counsel further submits that the plaintiff has not come to Court with clean hands. There

is a unilateral change in the service conditions of the defendant. Furthermore, the conditions of

repayment of the loan amount given by the plaintiff to the defendant for the training have been

altered without the consent of the defendant. There was a change in the seniority rules. The

defendants increments were not paid. Promotion has not been given. Thus the plaintiffs literally

compelled the defendants to leave the services. These are circumstances of their own making.

Therefore, it cannot be said that defendant has acted in breach of contract. Even otherwise, the

negative covenant conditions are onerous, unreasonable and unconscionable.

The contract has been signed under coercion and undue influence of the plaintiff as the plaintiff

had a dominant bargaining power. A perusal of Clause 23 shows that it gives the power to the

plaintiff to change all conditions of service without consent of the defendant or other employees.

It is submitted that the restraint of 7 years in any event is far too long. Last but not the last, it is

submitted that pilots are "workman" under Clause 9-A of the Industrial Disputes Act. Therefore,

the changes in seniority could only be made after giving a notice of change as required under the

Industrial Disputes Act.

Judgement

I (the Judge) have considered the arguments put forward by the learned Counsel. A perusal of the

submissions noted above would show that the learned Counsel have reiterated the arguments one

after the other, on both the sides. A perusal of Clauses 6 and 22 would clearly show that there is

an affirmative covenant followed by the negative covenant. On the basis of these covenants, the

defendants have agreed to serve the plaintiffs for a period of 7 years exclusively. They have

3 Mandatory injunction is an injunction which orders a party or requires them to do an

affirmative act or mandates a specified course of conduct. It is an extraordinary remedial

process which is granted not as a matter of right, but in the exercise of sound judicial

discretion. The court will normally grant a mandatory injunction in the following

circumstances; 1.The applicant will suffer serious harm if the same is not granted,

2. The applicant will most likely succeed at trial;

3.The respondent will not incur expenditure which would be disproportionate to the

applicants harm.

11

agreed that during the period of 7 years they will not take up employment with any other person,

organisation, company requiring them to perform similar duties as required to be performed by

the plaintiffs. They have also agreed not to engage in any similar business or vocation requiring

them to fly any other Airlines. In Golikari's case (supra) the Supreme Court was considering a

similar negative covenant. Therein the Clauses were as follows :

Clause 6 of the agreement provided :- "The employee shall, during the period of his employment

and any renewal thereof, honestly, faithfully, diligently and efficiently to the utmost of his power

and skill

(a) xxx xxx xxx

(b) devote the whole of his time and energy exclusively to the business and affairs of the

company and shall not engage directly or indirectly in any business or serve whether as principal,

agent, partner or employee or in any other capacity either full time or part time in any business

whatsoever other than that of the company."

Clause 9 provided that during the continuance of his employment as well as thereafter the

employee shall keep confidential and prevent divulgence of any and all information, instruments,

documents, etc. of the company that might come to his knowledge. Clause 14 provided that if the

company were to close its business or curtail its activities due to circumstances beyond its

control and if it found that it was no longer possible to employ the employee any further it should

have option to terminate his services by giving him three months notice or three months salary in

lieu thereof.

Clause 17 provided as follows :- "In the event of the employee leaving, abandoning or resigning

the service of the company in breach of the terms of the agreement before the expiry of the said

period of five years he shall not directly or indirectly engage in or carry on of his own accord or

in partnership with others the business at present being carried on by the company and he shall

not serve in any capacity, whatsoever or be associated with any person, firm or company

carrying on such business for the remainder of the said period and in addition pay to the

company as liquidated damages an amount equal to the salaries the employee would have

received during the period of six months thereafter and shall further reimburse to the company

any amount that the company may have spent on the employees training."

12

Interpreting the aforesaid Clause, the Supreme Court has held that negative covenants during the

period of contract of employment when the employee is bound to serve his employer exclusively

are generally not regarded as in restraint of trade and, therefore, do not fall under section 27 of

the Contract Act. In that case the defendant had been trained by the plaintiffs on the post of Shift

Supervisor. In this training the defendant acquired knowledge of the technique, process and the

machinery involved and certain other confidential documents. This confidentiality was sought to,

be breached by the defendant by seeking employment with the rivals of the plaintiffs. Thus, the

injunction is granted to protect the interest of the plaintiff. It was held that the negative covenant

was not unconscionable, oppressive or unreasonable. It was also held to be not against the public

policy.

The main question to be decided in these cases is whether the negative covenant is in restraint of

trade. Section 27 reads as under:

Agreement in restraint of trade void: Every agreement by which anyone is restrained from

exercising a lawful profession, trade or business of any kind, is to that extent void."

Whether or not the contract is in restraint of trade would depend upon whether the contract was

unreasonable, unfair or unconscionable. A contract imposing a general restraint would, in all

probability, be void. Partial restraint would prima facie be valid and, therefore, enforceable. In

order for the negative covenant to be valid, even the partial restraint would have to be reasonable

in the interest of the parties and of the public. In the case of covenants of restraint between

master and servant two question necessarily arise.

First what are the interests of the employer that are to be protected.

Second what is the remedy available to the employer to protect the interest.

In Golikari's case the Supreme Court was dealing with the weaving process which the plaintiff

was obliged under an agreement with the foreign collaborator to keep secret. The German

Company had agreed to transfer the technical know how to the plaintiff company to be used

exclusively, for the plaintiff company's Tyre Cord Yarn Plant at Kalyan. Therefore, the plaintiff

was obliged to enter into secrecy agreements with its employees. It was in these circumstances

that the defendant in that case was required to give a negative covenant of secrecy. Clause 9 of

the agreement specifically provided that the defendant shall keep confidential and prevent

divulgence of any of the information and documents etc. which may have come to his

13

knowledge. In such circumstances, the Supreme Court held that the plaintiff was entitled to be

protected in regard to their interest in the trade secret and secret process of manufacturing. This

protection was secured by restraining the defendant from divulging those trade secrets or by

putting into the use of the competitor.

In my view, the ratio of the judgment in Golikari's case is not applicable to the facts and

circumstances of the present case. It has been noticed above that all the defendants have been

sent on an advanced training course to enable them to fly new generation aeroplanes. It is

nobody's case that this training is a well guarded secret of the plaintiffs. In fact the training can

be obtained by any pilot by paying the requisite training charges. Even the pilots in Sahara

Airlines have to undergo the same training. The plaintiffs also cannot claim to have any interest

in the training acquired by the defendants as this is a skill which belongs exclusively to the

defendants. The defendants had received no special knowledge of any trade secret which

belonged exclusively to the plaintiffs. Thus the ratio in Golikari's case would not be applicable in

this case.

Mr. Chagla had submitted that breach of contract is clear. An enormous amount of money has

been spent on the training of the defendants. The Court would be failing in its duty if the

injunction is not granted as it would lead to inducements being offered by competitors to lure

away the employees of the plaintiffs. There would be no sanctity of contract. In fact, learned

Counsel submitted that this was a blatant case of poaching by the competitors. The same

arguments have been reiterated by Mr. Vahanvati and Mr. Dwarkadas. These arguments, in my

view, rather than helping the plaintiffs, are the very reasons for which the relief of injunction

ought not to be granted. In my view, the covenant is designed merely to prevent the defendants

from taking up employment with the competitors. This kind of a restraint, in my opinion, which

is in gross is not entitled to any protection. All the learned Counsel from the plaintiffs have

submitted that 8 pilots have left and joined Sahara Airlines. They have been offered higher

salary. Sahara Airlines would now reap the rewards of the training which has been made possible

by the plaintiffs. What has been submitted by the learned Counsel has in fact also been pleaded

in the plaint in paragraph 26, which has been reproduced in para 11 hereinabove. A perusal of the

same clearly shows that the plaintiff is only interested that the defendants should not accept

employment with Sahara Airlines. This becomes evident from the fact that there are only two

scheduled Airlines viz. Jet Airways and Sahara Airlines in which the Aircraft B-737-300/400/500

are being operated. It is also a matter of fact that there are large number of pilots who are

unemployed and would be ready and willing to take up employment with the plaintiffs in place

14

of the defendants. Since the plaintiffs has no property/proprietary right in the skill acquired by

the defendants, no protection can be granted on the basis of the negative covenant. The

apprehension expressed by the learned Counsel for the plaintiffs that if an injunction is not

granted, then the pilots are likely to leave and join the competitor is no ground for granting the

drastic relief of injunction against the defendants. It is common ground between the parties that

earlier sixteen pilots had left Sahara Airlines and joined Jet Airways. The plaintiffs did not see

anything wrong in poaching the pilots from Sahara Airlines. It is settled law that the relief of

injunction can only be granted to protect the proprietary interest of the plaintiffs. To prevent the

pilots from leaving the plaintiffs and joining the competitor would not be protection of any

proprietary interest of the plaintiffs. Such a protection could have been provided by the plaintiffs

themselves by offering better condition of service than the competitor. It would clearly be against

public policy to compel the defendants to be forced to work with the plaintiffs merely because of

the covenant. It would amount to compelling disgruntled employees to work for an equally

disgruntled employer. This would not be in the interest of anyone. I am unable to agree with the

submissions of Mr. Chagla to the effect that if injunction is not granted, then there would be no

sanctity of contract. I am also unable to agree that public interest would be adversely affected as

the Airlines might cut corners in the training of the pilots if the negative covenant is not enforced

by way of injunction. Sanctity of contract has to be maintained by all parties to the contract. It

cannot be that the contract is sacrosanct for the defendants and not so for the plaintiffs. Thus the

conduct of the plaintiffs is also relevant. The conduct of the plaintiffs makes it abundantly clear

that it is following purely laissez-faire policy of business. Its primary aim is to capture the

maximum amount of domestic Air Traffic. It is not in business for any altruistic or philanthropic

reasons. It is, therefore, a little difficult to accept the submission of the learned Counsel that the

Airline would cut corners in the training which would directly affect its share of traffic which in

turn would affect its economic viability. I, therefore, hold that no public interest will be subserved by the grant of injunction. Further, this would be clearly against section 41(e) of the

Specific Relief Act which provides that no injunction ought to be granted to prevent the breach

of a contract the performance of which would not be specifically enforced. In my opinion, Mr.

Naphade is correct in his submission that the only anxiety of the plaintiffs is to protect

themselves from competition of Sahara Airlines. The negative covenant is not to protect any

proprietary interest of the plaintiffs, for they have none. It has already been narrated in the facts

above that the defendants have in fact financed their own training. The plaintiffs have merely

advanced a loan which was being recovered from the defendants in installments. Therefore, even

factually the position would not be the same as in Golikari's case. In that case the defendant had

been trained at the expense of the plaintiffs therein. I am of the considered opinion that the

15

negative covenant is unconscionable, one sided, unreasonable and not for the protection of any

proprietary interest of the plaintiff. Thus the negative covenant cannot be enforced by way of

injunction.

I am unable to agree with the submission of Mr. Dwarkadas that Lodha, J., would have granted

the injunction if the Court had come to the conclusion that there was an implied negative

covenant. There is no indication to this effect in the judgment of Lodha, J. On the contrary

Lodha, J., has come to the conclusion that even if it is assumed that there is an implied negative

covenant, still the relief of injunction cannot be granted to the plaintiffs. Even in the Coca Cola

case, the Supreme Court has categorically held that the Court is not bound to grant an

injunction in every case and an injunction to enforce a negative covenant would be refused if it

would indirectly compel the employees either to idleness or to serve the employer. Lodha, J., has

followed the law laid down by the Supreme Court and has also come to the conclusion that grant

of injunction would render the defendant, in that case, either idle or compel him to serve the

plaintiff. It is a settled principle of law that the relief of injunction should not be granted if it

would compel the employee to serve the employer or when the grant of injunction will lead to

the employee remaining idle. Grant of an injunction which would lead to either of these two

results would not be in public interest. The plaintiffs had relied on the observations of the

Supreme Court in Golikari's case that merely because the employees may be compelled to work

on a lesser remuneration is no consideration against enforcing the covenant. These observations

are of no avail to the plaintiffs in the present case. The defendants have at their own expense

acquired the training for flying new generation Aeroplanes. There are only two scheduled

Airlines, plaintiff and Sahara Airlines in which these Aeroplanes are operational. An injunction

restraining the defendants from flying B-737-300/400/500 is bound to render them idle. It would

clearly also amount to specific performance of the contract in that the defendants would either

have to remain idle or will be compelled to serve the plaintiff alone. Lodha, J., has refused to

grant the injunction even after assuming that a negative covenant can be implied from the

agreement. In paragraph 21 of the judgment, Lodha, J., has observed as follows;

"21. In view of the aforesaid ratio of the Supreme Court in M/s. Gujarat Bottling Co. Ltd.

(supra) it is clear that Court is not bound to grant an injunction in every case and an injunction

to enforce a negative covenant would be refused if it would indirectly compel the employee to

idleness or to serve the employer. In the present case, in my considered opinion, the negative

covenant cannot be implied and, therefore, question of grant of injunction to enforce the negative

covenant would not arise. Even if for the arguments sake it is assumed that the parties had

16

presumed intention that the defendant shall serve the plaintiff alone exclusively and shall not

serve anybody else during the period of the contract, grant of the injunction in the facts and

circumstances of the case would definitely lead either the defendant to remain idle or he shall be

compelled to serve the plaintiff and if that be the reason, in my view the plaintiff was not entitled

to injunction and the temporary injunction granted by the trial Court cannot be sustained. The

defendant is admittedly a Pilot having experience in flying aircrafts. There is no dispute that the

defendant has acquired the training for flying the sophisticated Boeings i.e. 737-400 and such

other aircrafts. The job of a pilot and that too of pilot in command for which the defendant has

been engaged by the plaintiff is not an ordinary job nor having acquired such training and spent

so many years in flying, he can be expected to serve as member of the ground staff in any other

airline as suggested by the learned Counsel for the plaintiff-respondent, a qualified and trained

pilot having acquired that skill can either do that job or no job at all and, therefore, if injunction

granted by the trial Court is allowed to sustain or the plaintiff is granted such injunction against

the defendant either the defendant would remain idle because he cannot work on any other job

or that he will be compelled to serve the plaintiff alone. It is not the matter of remuneration but it

is the matter of job for which man is equipped, trained and skilled and a person having acquired

training and still as pilot of flying sophisticated Boeings, he cannot be expected to do a job of

ground staff. Obviously therefore, injunction granted by the trial Court would either compel the

defendant to remain idle or would force him by circumstances to serve the plaintiff and I am

afraid if injunction granted to the plaintiff would result in such consequence, the injunction

cannot be justified. Therefore, in my view, the trial Court cannot be said to have exercised its

discretion while granting injunction in accordance with law and well settled principles."

I am in respectful agreement with the observations made by Lodha, J., and would decline the

claim for injunction. Another reason for refusing the relief of injunction is that prima facie I am

of the view that the plaintiffs have failed to perform the contract so far as it was binding on them

and cannot be permitted to take advantage of its own wrong. Proviso to section 42 of the Specific

Relief Act clearly requires the plaintiffs to perform its part of the obligations in order to seek the

relief of injunction which is otherwise prohibited by virtue of section 41(e) of the Specific Relief

Act.

Looking at the facts and circumstances of these cases it cannot be held that the restriction is

reasonable and fair and not one sided. Inspite of the fact that the defendants have not divulged

any trade secret or information which is not available to the general public, they are sought to be

restrained from exercising their profession. The defendants have undergone extensive specialised

17

training and spent huge sums of money. Now they are sought to be prevented from making any

use of this training merely because the training would be used whilst they are in the employment

of the competitor of the plaintiffs. A negative covenant, the sole purpose of which is to avoid

competition, cannot be treated to be a covenant by which the covenantee seeks to protect its

proprietary interest. Whether or not a contract is reasonable has to be seen by examining as to

what is the purpose of the restraint and as to whether it is justified. These principles have been

clearly stated in the case of (Shree Gopal Paper Mills Ltd. v. Surendra K. Ganeshdas Malhotro Y,

, Justice A.N. Ray has observed as follows:

"21. In contracts of service it is the proprietary interest owned by the master that requires

protection. As Lord Parkar said in 1961-1 AC 688.

"The reason, and the only reason for upholding such a restraint on the part of an employee is that

the employer has some proprietary right whether in the nature of trade connection or in the

nature of trade secrets, for the protection of which such a restraint is - having regard to the duties

of the employee - reasonably necessary. Such a restraint has, so far as I know, never been upheld

if directed only to the prevention of competition or against the use of a personal skill and

knowledge acquired by the employee in his employer's business."

In master and servant contracts restraint can be imposed upon a servant in respect of trade secrets

and business connection of the master. In the case of Forster and Sons Ltd. v. Suggett, the works

manager of the plaintiff who were chiefly engaged in making glass and glass bottles was

instructed in certain confidential methods concerning inter alia the correct mixture of gas and air

in the furnaces. He agreed that during the five years following the determination of his

employment he would not carry on in the United Kingdom or be interested in glass bottle

manufacture or in any other business connected with glass making as conducted by the plaintiffs.

The restraint for protection of trade secrets was held to be reasonable. It is indispensable that the

employer must prove definitely that the servant has acquired substantial knowledge of some

secret process or mode of manufacture used in the course of his business. In our country the

restriction beyond the period of employment would not however be valid. Similarly, an employer

is entitled to protect his trade connection. The nature of the business and the nature of the

employment are important considerations justifying a restraint. It may appear that the servant had

no access to the trade secrets of his master or to his customers. If that is so, the covenant is in

gross and unenforceable. As Farwell, J., said in Town End v. Jaran,

18

"Now, if one man apart from any business takes a covenant in gross from another man, that he

will not trade at all, that is simply oppressive. He does not require it to protect his own interest,

because he has no interest to protect."

In the Herbert Morris case, Lord Atkinson said that an oppressive agreement meant that it

would, if enforced, deprive a person for lengthened period of the power of employing that

mechanical and technical skill and knowledge which his own industry, observation and

intelligence have enabled him to acquire in the very specialised manufacturing business, thus

forcing him to begin life afresh as it were, depriving him of the means of supporting himself and

his family. Lord Atkinson further said that the general public suffer with him for it is in the

public interest that a man should be free to exercise his skill and experience to the best advantage

for the benefit of himself and of all those who desire to employ him.

In all cases of covenants of restraint between master and servant the two questions are first what

are the interest of the employer that are to be protected and secondly, against what is he entitled

to have them protected. The master is entitled to be protected in regard to his interests in trade

secrets and secret process of manufacture. That protection is secured by restraining the employee

from divulging those trade secrets or putting them to the use of the servant, the master is also

entitled to be protected against invasion of his customers or clientele but the master is not

entitled to be protected against competition...

The aforesaid observations in my view are sufficient to negative the submissions of the learned

Counsel for the plaintiffs to the effect that Jet Airways are entitled to be protected on the basis of

the negative covenant.

All the learned Counsel for the defendants had submitted that in view of Clauses 20, 21 and 23,

there is no negative covenant. I am unable to agree with the submission made by the learned

Counsel. Firstly merely providing for liquidated damages will not cut into the scope of the

negative covenant. In Golikaris case there was a provision for liquidated damages. Even then the

injunction was granted. Similarly the provision for probation or for termination of service prior

to the period of 7 years would not mean that there is no negative covenant. A bare perusal of

these provisions would show that Clause 21 is similar to Clause 17 in Golikaris case. In that

clause it is provided that in the event of the employee resigning or abandoning the services, the

employee would pay to the Company liquidated damages as stipulated therein. In Clause 21 it is

stipulated that in case of resignation or leaving the services, the employee shall make good and

pay to the company the pro rata cost in respect of training. This kind of a provision has been

19

held by the Supreme Court in Golikari's case not to be any hindrance for the grant of the relief of

injunction. In the present case Clause 21 provides for liquidated damages. Clause 23 gives an

option to the plaintiffs to terminate the services of the employee even after confirmation by

giving three months notice in writing or payment of three months salary in lieu of the notice. The

employee also has the option to leave the services of the plaintiffs by giving 3 months notice in

writing. The company can even waive the notice. All these clauses read together leave no manner

of doubt that the period of employment can be cut short either by the employer or by the

employee. This has no effect on the 7 year period for which the restrictive covenant is to run.

Even if the employee leaves the employer on the basis of exercise of his option under Clause 23

he would still be bound to perform the negative covenant provided the covenant is not in restraint

of trade, being unreasonable and unconscionable. I am unable to agree with the submission of

Mr. Tulzapurkar that merely because liquidated damages have been provided no order of

injunction can be issued in view of section 42(h) of the Specific Relief Act. This point has been

specifically negatived by the Supreme Court in Golikari's case. Therefore, it is not necessary to

give any further reasons for rejecting the submission. To avoid any confusion it is, however made

clear that the negative covenant in the present case does not satisfy the test to qualify for any

protection by way of injunction.

Mr. Tulzapurkar had rightly relied on the observations of the Supreme Court in paragraph 50 of

the Coca Cola case which are as under :

"50. In this context, it would be relevant to mention that in the instant case GBC had approached

the High Court for the injunction order, granted earlier, to be vacated. Under Order 39 of the

Code of Civil Procedure, jurisdiction of the Court to interfere with an order of interlocutory or

temporary injunction is purely equitable and, therefore, the Court, on being approached, will

apart from other considerations, also look to the conduct of the party invoking the jurisdiction of

the Court, and may refuse to interfere unless his conduct was free from blame. Since the relief is

wholly equitable in nature, the party invoking the jurisdiction of the Court has to show that he

himself was not at fault and that he himself was not responsible for bringing about the state of

things complained of and that he was not unfair or inequitable in his dealings with the party

against whom he was seeking relief. His conduct should be fair and honest. These considerations

will arise not only in respect of the person who seeks an order of injunction under Order 39,

Rule 1 or Rule 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure but also in respect of the party approaching the

Court for vacating the ad interim or temporary injunction order already granted in the pending

suit or proceedings."

20

In view of the above, it is not only the conduct of the defendants but also the conduct of the

plaintiffs which has to be scrutinised. It is an accepted fact that the terms and conditions of

service of the defendants have been unilaterally altered by the plaintiffs. It has been emphatically

argued by all the learned Counsel for the plaintiffs that the plaintiffs were entitled to do so. It has

been submitted that the grievances put forward by the plaintiffs were imaginary. I am unable to

accept the submissions. Firstly the defendants were made to pay for the training. Large sums of

money were being deduced from the salary of the defendants in order to repay the loan amount.

Seniority of the defendants have been affected in such a manner that their chances of promotion

have been adversely affected. The terms and conditions of the service as contained in the

appointment orders have been altered to the detriment of the defendants with retrospective effect.

The installments for repayment of the loan have been enhanced contrary to the provisions

contained in the initial letter of appointment dated 30th April, 1998. From this it becomes

obvious that the accrued rights of the defendants are sought to be taken away by amendments in

the policy decisions retrospectively.

Prima facie, I am of the view that this is sufficient breach of contract to disentitle the plaintiffs

from the relief of injunction which is to be granted on the basis of equity and good conscience. I

am also of the considered opinion that irreparable loss would be caused to the defendants, if they

are compelled to remain idle. All these defendants are experienced pilots having served in the

Navy and other organisations. They are all persons having family responsibilities. Thus

compelling them to remain idle would certainly tantamount to ruining their career as well as

family life. The Court cannot be oblivious to the human consequences which an order of

injunction would cause. On the other hand non-grant of injunction would not cause any

irreparable loss to the plaintiffs. Earlier the plaintiffs had quite merrily and successfully poached

16 pilots from Sahara Airlines. Now 8 pilots left Jet Airways and joined Sahara Airlines. Prima

facie, it appears that the conduct of the plaintiffs was such that the defendants had little choice

but to seek employment elsewhere. It is a hallowed principle of law, that those who seek equity

must do equity. Conduct of the plaintiffs can hardly be described as clean or commendable. I am

also of the considered opinion that any inconvenience which had been caused by the resignation

of the defendants was merely temporary. Thus the balance of convenience also lies in favour of

the defendants. Furthermore, the plaintiffs can be suitably compensated by award of damages in

the event the suit is finally decreed against the defendants and in favour of the plaintiffs. In my

view, the plaintiffs have failed to show prima facie any legal or equitable right for the grant of

injunction.

21

The case dismissed with costs.

+++++++++++++++

You might also like

- Scourge of The Sword Coast BookDocument85 pagesScourge of The Sword Coast BookDaniel Yasar86% (7)

- Title Pages 1. 2: 22167 Sexuality, Gender and The Law STUDENT ID: 201604269Document21 pagesTitle Pages 1. 2: 22167 Sexuality, Gender and The Law STUDENT ID: 201604269Joey WongNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Delta Air Lines - Based OnDocument5 pagesAn Analysis of Delta Air Lines - Based OnYan FengNo ratings yet

- State Secret Chapter 2Document17 pagesState Secret Chapter 2bsimpichNo ratings yet

- Aviation Industry and Its ChallengesDocument19 pagesAviation Industry and Its ChallengesDinesh PalNo ratings yet

- 10-Cisa It Audit - BCP and DRPDocument27 pages10-Cisa It Audit - BCP and DRPHamza NaeemNo ratings yet

- JetBlue Study ProjectDocument36 pagesJetBlue Study ProjectIrna Azzadina100% (1)

- BSNL Payslip February 2019Document1 pageBSNL Payslip February 2019pankajNo ratings yet

- History of Freemasonry Throughout The World Vol 6 R GouldDocument630 pagesHistory of Freemasonry Throughout The World Vol 6 R GouldVak AmrtaNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Merchant Shipping Act 2020Document249 pagesBangladesh Merchant Shipping Act 2020Sundar SundaramNo ratings yet

- Strengths in The SWOT Analysis of IndigoDocument2 pagesStrengths in The SWOT Analysis of IndigoJyoti joshiNo ratings yet

- Jet AirwaysDocument11 pagesJet AirwaysAnonymous tgYyno0w6No ratings yet

- Separation, Delegation, and The LegislativeDocument30 pagesSeparation, Delegation, and The LegislativeYosef_d100% (1)

- RFP For Jet Airways v2Document17 pagesRFP For Jet Airways v2rahulalwayzzNo ratings yet

- RA 7160 Local Government CodeDocument195 pagesRA 7160 Local Government CodeStewart Paul Tolosa Torre100% (1)

- Jet Blue Case of Service MarketingDocument4 pagesJet Blue Case of Service MarketingtsopuewuNo ratings yet

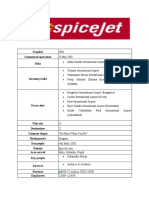

- Spicejet AirlinesDocument15 pagesSpicejet Airlinesshekhar_navNo ratings yet

- Jet Airways SWOT and Strategy AnalysisDocument31 pagesJet Airways SWOT and Strategy AnalysisVipul ShettyNo ratings yet

- Jet Airways - Strategy MGMTDocument93 pagesJet Airways - Strategy MGMTShubha Brota Raha100% (2)

- Case Study of Jet AirwaysDocument2 pagesCase Study of Jet AirwaysrishitkhakharNo ratings yet

- Case Study - IR Problems at Jet AirwaysDocument4 pagesCase Study - IR Problems at Jet Airwayskadam.sandip2865No ratings yet

- Jet Airways Organizational Structure and HistoryDocument25 pagesJet Airways Organizational Structure and HistoryTriptiNo ratings yet

- Jet AirwaysDocument4 pagesJet AirwaysKumar SachinNo ratings yet

- Normal Operations Report: Insourcing vs Outsourcing AnalysisDocument2 pagesNormal Operations Report: Insourcing vs Outsourcing Analysisnikitajain021No ratings yet

- Service Marketing Assignment: Indigo AirlinesDocument16 pagesService Marketing Assignment: Indigo AirlinesSammyNo ratings yet

- Jet Airways: Buyout and IssuesDocument9 pagesJet Airways: Buyout and IssuesShubhangi DhokaneNo ratings yet

- Strategy Indigo Report Group 7Document26 pagesStrategy Indigo Report Group 7Vvb SatyanarayanaNo ratings yet

- A Presentation On Merger of Air India & Indian Airlines: by D.Pradeep Kumar Exe-Mba, Iipm, HydDocument41 pagesA Presentation On Merger of Air India & Indian Airlines: by D.Pradeep Kumar Exe-Mba, Iipm, Hydpradeep3673100% (1)

- Presentation On Aviation IndustryDocument20 pagesPresentation On Aviation Industryaashna171No ratings yet

- Branding Strategy and Market Share: A Case Study of Jet AirwaysDocument8 pagesBranding Strategy and Market Share: A Case Study of Jet Airwaysakshat mathurNo ratings yet

- Crisis and Debt Restructuring at Kingfisher AirlinesDocument5 pagesCrisis and Debt Restructuring at Kingfisher AirlinesAnk's SinghNo ratings yet

- Indian Airlines HR WoesDocument5 pagesIndian Airlines HR WoesPraveen Sah100% (2)

- Jet AirwaysDocument3 pagesJet AirwaysYogesh Gilly0% (1)

- 2G Robotics Casesummary Group7Document2 pages2G Robotics Casesummary Group7Ishika RatnamNo ratings yet

- Jet Airways Crisis: Reasons and Way ForwardDocument9 pagesJet Airways Crisis: Reasons and Way Forwardshraddha tiwariNo ratings yet

- Commercial Aviation Industry Suppliers Conference: Speednews 28Th AnnualDocument1 pageCommercial Aviation Industry Suppliers Conference: Speednews 28Th Annuala_sharafiehNo ratings yet

- Nov 2019Document39 pagesNov 2019amitha g.sNo ratings yet

- Jet Airways Case StudyDocument5 pagesJet Airways Case StudyVaibhav golaniNo ratings yet

- Jet AirwaysDocument25 pagesJet AirwaysNaman AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Indian Airlines HR Woes Lead to LossesDocument6 pagesIndian Airlines HR Woes Lead to LossesNihaal Hussain100% (1)

- Competitor Analysis Indigo AirlinesDocument1 pageCompetitor Analysis Indigo AirlinesBen Jais0% (1)

- AirlinesDocument14 pagesAirlinespriyanka1608No ratings yet

- Jet Airways-Research MethodologyDocument36 pagesJet Airways-Research MethodologyNiket DattaniNo ratings yet

- Case External Analysis The Us Airline IndustryDocument2 pagesCase External Analysis The Us Airline IndustryPenujakIPJB0% (1)

- Air IndiaDocument12 pagesAir IndiaSathriya Sudhan MNo ratings yet

- Indigo AirlineDocument23 pagesIndigo AirlineSayali DiwateNo ratings yet

- Air IndiaDocument32 pagesAir IndiaPiyush KamraNo ratings yet

- 07c Low-Cost Carriers in India SpiceJets PerspectiveDocument4 pages07c Low-Cost Carriers in India SpiceJets PerspectiveSubhadra Haribabu100% (1)

- Instructor Manual Flying Too Low Air India 2009 & BeyondDocument7 pagesInstructor Manual Flying Too Low Air India 2009 & BeyondArunkumarNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Air IndiaDocument6 pagesCase Study On Air IndiaHimanshuRajNo ratings yet

- AI-IA Merger: What Went WrongDocument10 pagesAI-IA Merger: What Went WrongShankar VasuNo ratings yet

- Voltas GrowthDocument30 pagesVoltas Growthachaluec100% (1)

- Jet Airways ProjectDocument28 pagesJet Airways ProjectAmit SinghNo ratings yet

- STP Spice JetDocument6 pagesSTP Spice JetPranky PanchalNo ratings yet

- AI-Official Name, Headquarters & OwnersDocument3 pagesAI-Official Name, Headquarters & OwnersZamora Enguerra EmmalyneNo ratings yet

- A Report On Corporate Governance of Jet Airways: Submitted To: Submitted By: Prof. S. Bidwai Samir Kumar Singh 10BSP1291Document5 pagesA Report On Corporate Governance of Jet Airways: Submitted To: Submitted By: Prof. S. Bidwai Samir Kumar Singh 10BSP1291hell220587No ratings yet

- Jet AirwaysDocument32 pagesJet AirwaysPradeep100% (7)

- Indian Airline HR ProbsDocument25 pagesIndian Airline HR Probsraunak3d9100% (3)

- Neil Majumder - Aviation Industry - IndiGo AirlinesDocument19 pagesNeil Majumder - Aviation Industry - IndiGo AirlinesNeil MajumderNo ratings yet

- Case #7 FinalDocument4 pagesCase #7 Finalzatlas1No ratings yet

- Air India ProjectDocument47 pagesAir India ProjectPulkit jangirNo ratings yet

- Kingfisher AirlinesDocument10 pagesKingfisher Airlinesswetha padmanaabanNo ratings yet

- This Study Resource Was: Chotukool Case Study Answer OneDocument2 pagesThis Study Resource Was: Chotukool Case Study Answer OneMelvin ShajiNo ratings yet

- Creating an Effective Airline Configuration for the Indian MarketDocument21 pagesCreating an Effective Airline Configuration for the Indian MarketManoj JosephNo ratings yet

- Sathiyaselan A L Krishnan Ors V Flyfirefly SDN BHDDocument12 pagesSathiyaselan A L Krishnan Ors V Flyfirefly SDN BHDZaki ShukorNo ratings yet

- The Advantaged Crew Employment-Contract-Agreement (Jackson George Pereira)Document5 pagesThe Advantaged Crew Employment-Contract-Agreement (Jackson George Pereira)Sylvanus JajaNo ratings yet

- 27 LWV Construction v. DupoDocument5 pages27 LWV Construction v. DupoMarianne Hope VillasNo ratings yet

- VFS Global Services Private Limited Vs Suprit RoyM071022COM411842Document7 pagesVFS Global Services Private Limited Vs Suprit RoyM071022COM411842RATHLOGICNo ratings yet

- 12 Singapore AL Vs Paño 1983 AbandonmentDocument12 pages12 Singapore AL Vs Paño 1983 AbandonmentJan Igor GalinatoNo ratings yet

- AFN 132 Homework 1Document3 pagesAFN 132 Homework 1devhan12No ratings yet

- 2020.11.30-Notice of 14th Annual General Meeting-MDLDocument13 pages2020.11.30-Notice of 14th Annual General Meeting-MDLMegha NandiwalNo ratings yet

- Uyguangco v. CADocument7 pagesUyguangco v. CAAbigail TolabingNo ratings yet

- HSG University of St. Gallen MBA Program Employment ReportDocument6 pagesHSG University of St. Gallen MBA Program Employment ReportSam SinhatalNo ratings yet

- Thomas T. Scambos, Jr. v. Jack G. Petrie Robert Watson, 83 F.3d 416, 4th Cir. (1996)Document2 pagesThomas T. Scambos, Jr. v. Jack G. Petrie Robert Watson, 83 F.3d 416, 4th Cir. (1996)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Duterte's 1st 100 Days: Drug War, Turning from US to ChinaDocument2 pagesDuterte's 1st 100 Days: Drug War, Turning from US to ChinaALISON RANIELLE MARCONo ratings yet

- Millionaire EdgarDocument20 pagesMillionaire EdgarEdgar CemîrtanNo ratings yet

- MC 09-09-2003Document5 pagesMC 09-09-2003Francis Nicole V. QuirozNo ratings yet

- USA Vs AnthemDocument112 pagesUSA Vs AnthemAshleeNo ratings yet

- B.Tech in Civil Engineering FIRST YEAR 2014-2015: I Semester Ii SemesterDocument1 pageB.Tech in Civil Engineering FIRST YEAR 2014-2015: I Semester Ii Semesterabhi bhelNo ratings yet

- Book 1Document9 pagesBook 1Samina HaiderNo ratings yet

- Appointment ConfirmationDocument5 pagesAppointment Confirmationrafi.ortega.perezNo ratings yet

- Accounting Voucher DisplayDocument2 pagesAccounting Voucher DisplayRajesh MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Feleccia vs. Lackawanna College PresentationDocument8 pagesFeleccia vs. Lackawanna College PresentationMadelon AllenNo ratings yet

- 1981 MIG-23 The Mystery in Soviet Skies WPAFB FTD PDFDocument18 pages1981 MIG-23 The Mystery in Soviet Skies WPAFB FTD PDFapakuniNo ratings yet

- Abhivyakti Yearbook 2019 20Document316 pagesAbhivyakti Yearbook 2019 20desaisarkarrajvardhanNo ratings yet

- Concessionaire Agreeement Between Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) and Maverick Holdings & Investments Pvt. Ltd. For EWS Quarters, EjipuraDocument113 pagesConcessionaire Agreeement Between Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) and Maverick Holdings & Investments Pvt. Ltd. For EWS Quarters, EjipurapelicanbriefcaseNo ratings yet

- Corporate Finance - Ahuja - Chauhan PDFDocument177 pagesCorporate Finance - Ahuja - Chauhan PDFSiddharth BirjeNo ratings yet

- Long Questions & Answers: Law of PropertyDocument29 pagesLong Questions & Answers: Law of PropertyPNR AdminNo ratings yet

- Islamic Studies Ss 1 2nd Term Week 2Document6 pagesIslamic Studies Ss 1 2nd Term Week 2omo.alaze99No ratings yet

- APPLICATION FORM FOR Short Service Commission ExecutiveDocument1 pageAPPLICATION FORM FOR Short Service Commission Executivemandhotra87No ratings yet