Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Chapter 1

Uploaded by

NicoletaAronCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 1

Uploaded by

NicoletaAronCopyright:

Available Formats

Chapter 1.

The Verb as a Lexical Class

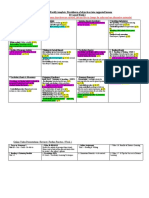

THE VERB AS A LEXICAL CLASS

Main issues:

1. Introduction and definition;

2. Verb classification criteria:

the criterion of lexical interpretation;

the criterion of formal interpretation;

the criterion of functional interpretation;

the criterion of structural interpretation;

the criterion of semantic interpretation.

Learning objectives

When you have studied this presentation you will be able:

- to distinguish between various kinds of verbs (applying various criteria)

- to analyze English verbs and characterize them from various perspectives

1. Introduction and definition

This approach consists of two major directions, (a) a modest inquiry regarding the types

of definitions provided for the English verb, and (b) the criteria according to which verbs are

more easily described in terms of common features (be they formal or semantic).

The definitions given to the verb as a lexical class vary not only from one school of

grammar to another but very often from one linguist to another also. Starting from didactical

purposes, if some definitions given to the verb are interpreted in point of the criterion they are

based on, one could distinguish the ontology, the form or the function to have been used as

primary criteria.

Grammarians very often say that it is practically impossible to give the exact and

exhaustive definitions of the parts of speech (Jespersen 1966: 66). In an attempt to exemplify

several types of definitions, we shall begin with a special version provided by Jespersen

(1966:67), who does not explicitly define verbs, but exemplifies them using the terms activity,

state and process:

[I] go, take, fight, surprise, eat, breathe, speak, walk, clean, play, call

([I am in] activity)

[I] sleep, remain, wait, live, suffer ([I am in] a state)

[I] become, grow, lose, die, dry, rise, turn ([I am in] a process)

Palmer (1971:59) critically quotes Nesfields definition of the verb which is even worse

[than that of the noun] because it is utterly uninformative A verb is a word used for saying

something about something else.1

Considering simplicity as a feature of the definitions given to the English verb, we shall

quote Alexanders version (1988:159) A verb is a word (run) or a phrase (run out of) which

expresses the existence of a state (love, seem) or the doing of an action (take, play). This is a late

20th century example of how simply a verb could be defined.

Nevertheless, there also exist complex definitions to combine two criteria, which is the

case of the following one which is based on a contrast between the noun group and the verb

group: a clause which is used to make a statement contains a noun group, which refers to the

person or thing that you are talking about, and a verb group, which indicates what sort of

action, process, or state you are talking about. (CollinsCobuild 1994:137)

Schibsbye (1970:1) defined the English verb taking into consideration the function and

the content of the verb. In his system of reference the verb is functionally defined as the

sentence-forming element of a word-group. Semantically, a definition of the verb in terms of its

1

J.C. Nesfields Manual of English Grammar and Composition was published in 1898.

1

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

content is the most comprehensive, but also the vaguest. Although defining the English verb is

a complex task, we suggest a simple version: the verb is the lexical class which includes words

expressing actions, events, states, and processes.

2. Verb Classification Criteria

The classification of English verbs may prove difficult because of the numerous criteria

to consider.

a) The criterion of lexical interpretation

Lexicologically, the English verbs may be the result of affixation, conversion,

contraction and back-formation. Affixation is carried out either by means of prefixes, suffixes

or both, when a prefix and a suffix added to one and the same word results in parasynthetic

formations. Most frequently used verb-forming suffixes are those of O.E., Latin or Greek origin.

The prefixes of O.E. origin include fore- (foresee, forego), out- (outlive, outnumber), and un-(uncover,

undo), while those of Latin origin could be exemplified by ante- (antedate), con- (concentrate) or

col- (collaborate, collocate). The verb/forming prefixes of Greek origin are usually exemplified by

anti- (anticipate) and en- (enlarge, enrich, encourage). The most frequently used verb forming

suffixes are en (strengthen, shorten), -ify (purify, humidify), -ise / -ize (oxidize, vaporize, civilise,

modernise. organise). The combination of the above mentioned affixes may act to produce

parasynthetic formations, such as simple simplify, oversimplify.

Since English is known to be a very flexible language, this flexibility may account for the

use of various parts of speech as verbs. Thus, as a result of conversion not only nouns may be

used as verbs (hand to hand, face to face, paper to paper, iron to iron) but adjectives and

adverbs, too (, black to black and slow to slow, out to out, respectively).

Very frequently used in pop music, especially American pop music, are the contracted

forms of verbs, such as aint (isnt or hasnt), lemme (let me), etc.

A very small number of verbs result from back-formation, where nouns are reduced to

verbs, as in the following examples baby-sitter to baby-sit, blood-transfusion to blood-transfuse,

or electrocution to electrocute.

b) The criterion of formal interpretation

Formally, the English verbs are regular (i.e. they form the past tense, the past participle

and the indefinite participle according to several spelling and pronunciation rules) or irregular

(where such rules are not applicable). The spelling rules for the basic forms of the regular verbs

are included in the great majority of the volumes dedicated to the English verb and that is why

we encourage the possible readers of this volume to look for further information in more

popular grammars.

c) The criterion of functional interpretation

If the function verbs play at sentence level represents the criterion of interpretation,

English verbs divide into: full meaning (main or notional) verbs and (semi-)auxiliary verbs.

c.1. Main verbs

The English verbs are defined in terms of form and function. Thus, verbs may have a full

meaning and play the key role to the whole sentence, which is the case with the lexical, main,

principal or full verbs. Very numerous, they represent the larger group of verbs in English and

they were denominated differently by the authors dealing with them. These notional (main,

lexical, principal or full verbs) have an independent meaning and function in the sentence. They

are used to form the simple verbal predicate and express an action, a state, an event of or about

the person or the thing denoted by the subject.

Palmer (1979:24) asserts that both modals and main verbs are basically verbs and both

2

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

can, in theory, share the same grammatical features. Nevertheless, things are different with the

two groups of verbs. The main verbs are thoroughly described in various grammars and

because of this reason they will not be insisted on in what follows. Our purpose is that of

spotlighting those features or details not very frequently presented in the specialist literature.

c.2. Auxiliary verbs

AUXILIARITY is a grammatical function which complements the verb phrase in various

ways (to suggest tense/aspect/interrogative/negative/imperative/modal) meanings. It is

expressed by the auxiliary or helping verbs. This group of verbs is mostly subdivided into

primary auxiliaries (BE, HAVE, DO) and modal auxiliaries (CAN, MAY, WILL, SHALL,

COULD, MIGHT, SHOULD, WOULD and MUST). Despite this classification, the auxiliary

verbs share one common syntactic feature: they may act as operators when holding the first

position within a verbal phrase. Thus, no matter whether expressed by primary or secondary or

modal auxiliaries, operators will help building the interrogative and negative verb forms, as

below:

Is she working on our project or on her paper?

Have they been building houses or blocks of flats?

They wont do that job.

She cannot play computer games.

Does she not know the answer?

Had they not finished that job before noon?

Auxiliarity may join together up to four components, as exemplified by Quirk et al.

(1985:120, figure 3.21):

He

might

Subject

aux1

have

been

being questioned

Verb phrase

aux2 aux3

aux4

main verb

by the police.

by-phrase

Auxiliary verbs reveal these basic features:

- they may be used in different positions within tense and aspect patterns,

- they are basically used as marks of grammatical categories, and quite often as modals,

link verbs, catenative verbs or as parts of compound predicates.

As marks of grammatical categories they:

- underlie the chronological order of events in a narration,

- describe the phase of a process/activity or even a state,

- underline who is doing something for someone else,

- ask questions or to give negative answers.

As link verbs (to be, to become, to get, to remain, to appear, and to grow) auxiliaries may be:

- followed by a predicative to make up the nominal predicate.

- a syntactical category which connects the subject with the predicative.

- a morphological category similar to but not identical with that of the auxiliary verbs.

Unlike the primary auxiliaries, link verbs actually represent the tense and they preserve some of

their lexical value.

A special category of verbs which partially play the part of an auxiliary are the catenative

verbs which may be either main or auxiliary verbs, depending on their grammatical context.

c.2.1. Primary Auxiliaries

Most of the auxiliaries have no lexical meaning, they are simply instruments by means

of which grammatical or stylistic shades of meaning are implied. They build up the analytical

forms of the English verb and may be marks of grammatical specifications, such as: tense

(perfect tenses), aspect (the progressive), tempo-aspectuality (perfective and imperfective

progressivity), mood (subjunctive, conditional and imperative), voice (active, passive or

3

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

causative patterns) and verbal forms (interrogative, negative and interrogative negative).

The auxiliary carrying out a stylistic function is TO DO, when it is emphatically used.

Even if mainly described for their use as labels for the grammatical categories of tense, aspect

and voice, they may frequently play the part of the verbal predicate of any sentence.

TO BE

This is the first of a long list of verbs, which may carry different meanings and may play

different roles. It is intended to facilitate the understanding of the flexibility, which

characterizes the English language.

As a main verb, BE expresses existence, and displays a copular function:

Jimmy is in his room.

That is the Empire State Building.

Mary is a beautiful girl.

As an auxiliary it can occur in two different patterns:

with the present participle of the full verbs to express aspectuality, i.e. progressivity

or perfective progressivity:

Miriam is learning Arabian.

Her behaviour has been improving lately.

or to express agentivity, with a main verb in the past participle:

Madonna has been awarded lots and lots of prizes.

Unlike the rest of the auxiliaries BE has a very high frequency of occurrence due to its flexibility

in being both a mark of aspectual forms as well as an auxiliary for passive constructions.

TO HAVE

Have displays two different functions in the grammar of the English language, acting

either as a main/full verb or as an auxiliary. In its full meaning value, have may be:

statively used it expresses possession and may be replaced by the verbs to own and to

possess or by the informal construction to have got:

They have (got)/possess an impressive house.

He does not have (own/possess) a ship but a fleet.

I have (got) a splitting headache.

dynamically used to subsume the senses of the verbs to receive, to take, to experience

and of many other verbs, which may result from the combination have + eventive object

as in to have a shower/dream/walk/talk/chat, etc..

Dynamically used the verb to HAVE normally expresses the interrogative and the

negative with the help of the verb to DO:

Does she have eggs with her breakfast?

Did you have a good time on your holidays?

With the same meaning, the verb may be followed by an object and a past participle in

order to express the fact that the grammatical subject of a sentence causes someone else to carry

out an action for him/her.

The causal meaning of the verb to have is obvious in a context as:

They

had

their house

redecorated

last year.

subject

causal have

object

past participle

time adverbial

Quirk et al. (1985:132) include this pattern among the uses of the verb to HAVE as a

main verb.

4

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

As an auxiliary the verb to HAVE is the mark of perfectivity (either simply used or in

combination with progressivity or modality):

She has just finished the translation.

Tim had already translated the poem when the teacher came in the lab.

He will have been working in this shop for two years by tomorrow.

You must have been working very long hours; you look exhausted.

She may have said the truth but I doubt it.

TO DO

As a main verb DO may be used:

transitively

She has done her homework and now she will go out for a walk.

intransitively, as a verbal predicate:

What have you been doing lately?

Nothing of importance, Im afraid.

as a pro-predication:

I cannot work as hard as I did when I was younger.

DO may also acquire various meanings depending on the object following it:

The boys will have to do the dishes: Mike will wash and Fred will dry them.

Ben has always done my old alarm clock. (to repair)

Bernadette has done really good essays this term. (to write)

Have you done the silver, Maureen? (to polish)

Betsy, do these potatoes, will you? (to peel or to cook)

As an auxiliary, DO is the mark of the interrogative and in association with the negation

not, the mark of the negative. Thus, with its auxiliary role it is used in:

yes/no questions:

Do they work hard?

special questions (in the present or past tense simple):

How did they start their business?

When do they usually meet to discuss the further steps of their business?

in negations (in the present or past tense simple):

They dont earn as much as they dreamt they would.

You didnt meet John yesterday.

in question tags (when the verb in the assertive is in the present or past tense simple):

They know the poem, dont they?

Thomas does not understand Italian, does he?

He stole his parents savings, didnt he?

in reduced clauses where DO is the dummy operator preceding the ellipsis of a

predication:

Emily runs faster than I do.

I did not watch TV but my sister did.

unlike the other verbs DO is used emphatically (when the verb to be emphasized is in

the present or past tense simple):

In emphatic positive constructions:

I do love my children.

Miriam did say she would help you, didnt she?

in persuasive imperative:

Do come and have a coffee with us tomorrow!

May I use your phone?

Yes, by all means, do.

5

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

The dual character of some verbs should be well remembered. It particularizes one

feature of the English verbs which arises from their flexibility in usage and which will be

mentioned again in the case of other verbs (catenatives or marginal modals).

c.2.2. MODAL AUXILIARIES

The last group of verbs is represented by the modals or semi-auxiliaries (the pseudoauxiliaries, or the quasi-auxiliaries) which have no independent meaning and consequently no

independent function in the sentence.

They are used as part of a (verbal or nominal) predicate. The main lexical meaning is

comprised in the second element of the predicate which is expressed by a noun, an adjective or

verbal. Syntactically, they are used in a finite form and express the predicative categories of

person, and the rest of them already mentioned in the foregoing.

As part of compound predicates these auxiliaries may equally accompany verbal and

nominal predicates:

They can go immediately. (compound verbal predicate)

They must be working very hard now. (compound verbal predicate)

They may be happy with Lucys success. (compound nominal predicate)

Modal verbs with a double status

The modal verbs which may display the two functions are shall, should, will and would.

SHALL

Shall behaves as an auxiliary in declarative sentences, in combination with the first

person subject (both in the singular and in the plural) to express futurity related to a present

reference:

I/we shall go on a packing tour on 1 July.

SHOULD

This is considered an auxiliary by those authors who admit the existence of the

conditional mood in English. According to them, SHOULD combines with a first person subject

and the bare infinitive of a main verb to suggest condition either seen from a present or past

perspective.

The combination I/we + should + present infinitive suggests present conditional:

I should go to the theatre on condition we went Dutch.

A merge cu tine la teatru cu condiia ca fiecare s-i plteasc biletul.

The pattern I/we + should + have + past participle suggests the idea of past conditional:

I should have gone to the theatre on condition we had gone Dutch.

Should is also considered as an auxiliary to express (perfect) futurity related to a past

reference:

I/we admitted I/we should go on a packing tour the next week.

I promised I should have copied the text in less than an hour.

WILL

This verb behaves as an auxiliary in declarative sentences having a second or third

person subject to suggest (perfect) futurity related to present reference:

You/She/They will go on a packing tour next month.

You/She/They will have made up their minds by this time tomorrow.

WOULD

As an auxiliary it is always preceded by a second or third person subject (singular or plural)

6

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

and followed by an infinitive to suggest condition:

the pattern You /she/ they + would + infinitive suggests

a) a present conditional (in subordinate clauses expressing a condition):

She would join him to the theatre on condition they went Dutch.

b) simple futurity related to a past reference:

They told us they would set out on a cruise on the Mediterranean next year.

the pattern you / she / they + would + have + past participle suggests:

a) a past conditional:

She would have accepted his invitation on condition they had gone Dutch.

b) perfect futurity related to a past reference:

The children promised their parents they would have done their homework before

5 p.m.

c.2.3. LINK/COPULATIVE VERBS

The link(ing) verbs link together the subject and the complement of one sentence to

express qualities or features regarding the subject. They may be used to convey two different

meanings: (1) to indicate a state or (2) to indicate a result. The former group of link verbs

represents the current linking verbs whose purpose is that of indicating a state and they

include to appear (happy), to lie (scattered), to remain (uncertain, perplexed, a bachelor), to seem

(restless, a mindful/thoughtful person, an efficient secretary, successful businessman), to stay

(young), to smell (sweet), to sound (surprised), to taste (bitter).

They seem supportive and trustworthy, but facts will prove what they are like.

The latter group i.e., the linking verbs expressing result indicate that the role of the

verb complement is a result of the event or process described in the verb. This group includes

examples as to grow (tired), to fall (sick), to run (wild), to turn (sour), to become (old-fashioned), to

get (nervous).

She is getting mad by the minute.

c.2.4. CATENATIVES

They represent a special group of verbs, which also have a dual character sharing the

position of auxiliaries but the morpho-syntactical patterns of the main verbs. Some

grammarians include among the catenatives to appear, to carry (on), to come, to fail, to get, to

happen, to manage, to seem, to start out, to tend, to turn out and to keep (on). As catenatives, their

main feature is that they are always followed by the infinitive.

Your brother wishes to marry my daughter, and I wish to find out what sort of a

young man he is. A good way to do so seemed to be to come and ask you, which I

have proceeded to do. ( H. James. W.S. 69-70)

Why, indeed, he does seem to have had some filial scruples on that head, as you

will hear. (J. Austen, 1970: 97)

Used as catenatives, to carry on, to go on, to keep (on) and to start out may be followed by

the present participle (in progressive constructions) or by the past participle (in passive

constructions):

The gardener started out / kept (on) /went on working in the garden.

Our team got beaten by the visitors. (Quirk et al. 1985: 147)

Auxiliaries represent a special class of verbs whose main purpose is that of helping the

full meaning verbs to express tenses, aspectual meanings, agentivity, as well as interrogative

and negative patterns.

Auxiliaries may be further subclassified into:

primary auxiliaries (BE, HAVE, DO) which are marks of progressivity, perfectivity,

7

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

i.e. of tempo-aspectuality, and interrogation and negation constructing patterns;

secondary (modal) auxiliaries which are, in turn, grouped into:

- central modals (which share a set of morpho-syntactic features) ;

- marginal modals (which share only some of the generally accepted morphosyntactic features of the modals)

In spite of various particular features, they still share one common trait: they behave as

operators (to switch their position with the subject to build the interrogative or to accept the

enclitic negation NOT to build the negative).

Unlike the primary auxiliaries, which are marks of grammatical categories, the

secondary/modal auxiliaries add various shades of meaning to the verb they accompany. They

are part of the compound verbal predicates and express the speakers personal opinion or

attitude.

Some English verbs may have a double status:

(1) they overlap meanings of full verbs and auxiliary verbs (BE, HAVE, DO);

(2) they develop characteristics of both primary and modal auxiliaries (SHALL,

SHOULD, WILL, WOULD)

(3) they display meanings and characteristics of both full verbs and modal auxiliaries

(NEED and DARE)

d) The criterion of structural interpretation

Structurally, verbs are divided into single-word verbs and multi-word verbs. The

considerable majority of the English verbs is represented by this first category.

1. The single-word verbs are simple (do, go, ask, look, take, etc.) and compound. The

compounding elements are parts of speech belonging to the same or to different sets:

adjective + verb:

to whitewash

noun+ noun/verb:

to pinpoint, to spotlight

adjective + noun/verb:

to highlight, to lowrate

preposition + verb:

to understand, to undertake, to undergo, to overestimate.

adverb + verb:

to broadcast, to outcast.

2. The multi-word verbs are not so numerous but they are very frequently used due to

their simple structure which makes them more practical for the economic, pragmatic and wellcalculated native speaker of English.

This label accounts for the so-called complex verbs, which like the simple-word verbs

may be further classified into four different subgroups, as follows:

type A combinations, also called the completive intensives are those complex verbs

where the particle does not change the meaning of the verb but it is used to suggest that the

action described by the verb is performed thoroughly, completely or continuously. For example,

in the case of spread out to the basic meaning of the verb to spread the ideas of direction and

thoroughness are added; in the case of to link up, the particle up adds the suggestion of

completeness to the initial meaning of connection and finally, in the case of to slave away and to

slog away, the element which is common to the two examples adds an idea of continuousness to

the idea of hard work.

type B combinations, also known as literal phrasal verbs are the combinations where

the verb and the particle both have meanings which may be found in other combinations and

uses, but there is overwhelming evidence that they (may) occur together: to fight back, to sing

8

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

back, to phone back, to strike back.

type C combinations, traditionally these are the verbs with compulsory preposition

these are the combinations where the verbs are always accompanied by a particular preposition

and they are not normally found without it. Some of the verbs with compulsory preposition are

to allude to, to aim at, to debate on/upon, to decide on/upon, to interfere with but their more

comprehensive list may be found in Annex 1.

type D combinations or phrasal verbs are more common in spoken or informal

English, but rarely used in formal or technical contexts.

Unlike the verbs with compulsory preposition, phrasal verbs share the following features:

- they may produce derived forms, i.e. nouns or adjectives:

If someone makes a getaway, they get away from a place in a hurry, perhaps after

committing a crime.

An off-putting person is s/he who puts you off or causes you to dislike him.

The two examples illustrate individual situations where the derived form may or may

not reverse the order of the compounding elements; there are cases where one combination may

produce these two derived forms, the identical pattern is turned into the derived nouns or

adjective but the newly formed derivative may also have the reversed order. This case may be

exemplified by the phrasal to break out, that is to begin suddenly:

A fire broke out on the 4th floor.

War broke out in Europe on 4th of August.

An outbreak is a sudden occurrence of something unpleasant: a severe outbreak of

food poisoning.

A break-out is an act of escaping from a place: we debated whether to make our

break-out on Christmas Eve.

- they accept a direct object between the verb proper and the particle:

To take off ones hat may also be expressed as

a) Take your hat off! and

b) Take it off!

- they may consist of more than two elements, as to look forward to, to look down on, to

put up with, etc.

Complex verbs may be made up of:

verb + preposition this structure accounts both for verbs with compulsory preposition

and for the phrasal verbs. We shall sustain the preceding statement with the example of the

verbs to look after and to fall:

A verb with compulsory

preposition

B phrasal verb

TO LOOK AFTER

Im looking after the dog chasing the They look after their sons children. (ei au

cat. (m uit dup...)

grij de)

TO FALL ON

to be/set on:

to attack suddenly:

My birthday falls on a Thursday this Terrorist groups were falling indiscriminately

year. ( cade pe)

on men and women in the street. (atacau

fr discriminare)

to hug eagerly with happiness and excitement:

People were falling on each other in delight

and tears. (se mbriau)

verb + adverb the meaning of the phrasal verbs cannot be inferred from its compounding

9

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

elements. Thus, there are some verbs which are accompanied by meaningfully opposite

particles but their new patterns do not convey the sum of the meanings of the compounding

elements. This is the case of the verb to lead: to lead in means to start a formal discussion or

meeting by making a short speech and to lead out means to connect directly (used about

buildings/ rooms, etc)

Two tiny rooms led off the living room.

Some other examples of patterns of this kind are included in Annex 2.

verb + adjective this structure is not so very actively used; for instance.

- to fall flat (to produce/have no response/result):

His joke fell flat, so he felt a bit embarrassed.

verb + adverb + preposition this pattern will be exemplified with:

- to lead up to to gradually guide the conversation to a point when they can

introduce the subject

- to hedge around with: to cause something to be very difficult or complicated : Her

freedom was hedged around with duties and restrictions.

- to fall in wih: to accept (a plan, idea, system) and not to try to change it:

I didnt know whether to fall in with this management

- to live up to/ match up to = to be as (good as ) the subject expects you to be.

The film didnt live up to my expectations. She succeeded in living up to her

extraordinary reputation.

e) The criterion of semantic interpretation

Although most of the English verbs bear more than one meaning, it is convenient for the

Romanian learner to have them classified into seven major semantic domains: activity,

communication, mental, causative, aspectual, of simple occurrence and of existence or

relationship. Biber et al. (1999) distinguish two kinds of meanings, the core meaning (the

meaning the speakers tend to think of when they first hear the word as a part of the

communication process) and the non-core meanings. Many verbs have multiple meanings

which derive from different semantic domains. A verb is most coming with a non-core

meaning.

1. Activity verbs: denote actions and events that could be associated with choice: bring,

buy, carry, come, give, go, leave, move, open, run, take, work.

The airline had opened the route on the basis that it would be the first of many.

They can be used transitively (for example: Even the smallest boys bought little pieces of wood

and threw them in) or intransitively (From Haworth they went to Holyhead and to Dublin)

2. Communication verbs: they are a special category of activity verbs that involve

communication activities: ask, announce, call, discuss, explain, say, shout, speak, state, suggest, talk,

tell, write.

You said you didnt have it.

I would shout my love to you.

3. Mental verbs denote a wide range of activities and states experienced by humans;

they do not involve physical action and do not necessarily entail volition. This category

includes: cognitive meanings (think, know), and emotional meanings expressing attitudes or

desires (love, want), perception (see, taste), receipt of communication (read, hear).

Many mental verbs describe cognitive activities that are relatively dynamic in meaning,

for example calculate, consider, decide, discover, examine, learn, solve, study. More stative in

meaning (describing cognitive states) believe, doubt, know, remember, understand and emotional

and attitudinal states (enjoy, fear, feel, hate, like, love, prefer, suspect, want).

The cognitive states:

We all believe that.

10

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

I somehow doubt it.

Emotional or attitudinal states:

I feel very sorry for you.

As a child he hated his weekly ritual of bathing.

4. Verbs of facilitation/causation are exemplified by allow, cause, enable, force, help, let,

require, permit. They indicate that some person or inanimate entity brings about a new state of

affairs.

He was permitted to leave the country.

Distributionally, these verbs often occur together with a nominalized direct object or

complement clause which reports the action that was facilitated. From a distributional point of

view, the causatives are followed by

a nominalized direct object:

Still other rules cause the deletion of elements from the structure.

This information enables the formulation of precise questions.

or by complement clauses:

Police and council leaders agreed to let a court decide the fate of the trees.

This law enables the volume of gas to be calculated.

5. Verbs of simple occurrence primarily report events (typically physical events) that

occur apart from any volitional activity; they are also called occurrence verbs and are

exemplified through become, change, happen, develop, grow, increase, occur.

The word of adults has once again became law.

The lights changed.

6. Verbs of existence/relationship report a state that exists between entities (most of

these verbs are link or copular verbs), which is the case of be, seem and appear. Some of them

report a particular state of existence (exist, live, stay) or a particular relationship between entities

(contain, include, involve, represent).

The state of existence is illustrated by:

I go and stay with them.

She had gone to live there during this summer holiday.

Relationship will be expressed by:

The exercise will include random stop checks by police, and involve special

constables and traffic wardens.

7. Aspectual verbs characterize the aspectual features related to an activity, event or

process, namely stage, duration, attitude of the subject, the (non)repeated character of an activity or

event and, last but not least the natural end or limit of a process or an activity. The stage of

progress of some other event or activity, typically reported in a complement clause following

the verb phrase. Examples of aspectual verbs should include: begin, continue, finish, keep, etc.

She kept running out of the garden.

He couldnt stop talking about me.

After another day he began to recover.

The duration of an activity or a process or even a state is the feature according to which

verbs may be considered durative and time-point verbs. The durative verbs which express

actions, processes and states which last in time may be illustrated by examples as to work, to

exist, to fly, to run, to sleep, to read, to study. The time-point or momentary verbs, expressing

actions and states spanning a very short interval of time): to come across, to run into, to start, to

enter, to get out, to win.

The attitude of the subject group of aspectual verbs denominate in/voluntary actions,

volition thus becoming a selecting feature for these aspectual verbs. Voluntary actions are

expressed by verbs of active perception as to watch, to look at, to contemplate, to listen to. The verbs

expressing involuntary actions/inert perception are to see and to hear.

11

Chapter 1. The Verb as a Lexical Class

The iteration/frequency divides the aspectual verbs of this group into semelfactives,

i.e. those verbs expressing an event or activity which lasts an extremely short time interval, such

as to hit, to knock, to cough, to jump, and iteratives whose meaning is that of underlying the fact

that the activity expressed by any of the semelfactives and many other verbs keeps repeating for

a specified moment or interval.

Telicity (or the reaching of a natural end, or limit/boundary) distinguishes between telic

and atelic verbs. The former group is represented by the verbs whose activity or process reaches

a natural end:

She is smoking a cigarette.

He is making a chair.

The latter group of verbs is outlined by those verbs whose contextual meaning shows

that no end will ever be reached:

She smokes (implicature she belongs to the category of smokers)

They make chairs (possible meaning to earn their living)

This is a controversial criterion because there may also exist situations where the

sentence subject is an inanimate entity which cannot be said to intervene and produce a natural

end to the action expressed by the verb:

The stone was rolling to the river bank.

Telicity, therefore, distinguishes between the uses of progressive or common verb forms

in the correct production of an English sentence.

Conclusions

This course aimed at offering a wide range of criteria useful in the understanding of the

English verb system. By and large, features of English verbs indicate that:

- main and auxiliary verbs behave differently in statements, interrogations and negations;

- regular and irregular verbs show different grammatical patterns in statements,

interrogations and negations;

- modality, as an issue peculiar to the English language, requires not only grammatical

knowledge and experience but a clear understanding of its concepts and implicatures,

also;

- modals verbs represent a high degree of difficulty verbal class, due to both their

morphological features and to their semantics which relies mainly on the context they

are part of;

- the semantic classification of verbs is helpful in the learning of aspectual distinctions,

which are difficult to understand for Romanian learners since aspect is not a fullyrepresented grammatical category in the Romanian verb system.

12

You might also like

- Actor - Fisa 3Document3 pagesActor - Fisa 3NicoletaAronNo ratings yet

- Modality in English ProverbsDocument12 pagesModality in English ProverbsNicoletaAron100% (1)

- New Microsoft Office Word DocumentDocument12 pagesNew Microsoft Office Word DocumentNicoletaAronNo ratings yet

- Raei 11 11Document17 pagesRaei 11 11Ana JovanovicNo ratings yet

- DocumenteDocument11 pagesDocumenteNicoletaAronNo ratings yet

- Rhetorical QuestionsDocument2 pagesRhetorical QuestionsNicoletaAronNo ratings yet

- Last ConversDocument21 pagesLast ConversNicoletaAronNo ratings yet

- ListaDocument4 pagesListaNicoletaAronNo ratings yet

- Linking Verb: Lungu Oana - Lorelei, EF Linking VerbsDocument3 pagesLinking Verb: Lungu Oana - Lorelei, EF Linking VerbsNicoletaAronNo ratings yet

- Mecanica InimiiDocument182 pagesMecanica InimiiIulia Bi100% (5)

- Masterplan Turism BalnearDocument55 pagesMasterplan Turism BalnearMiha DmdNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Irregular VerbsDocument3 pagesIrregular Verbsemece7No ratings yet

- Adjective ClauseDocument8 pagesAdjective ClausePutri SaskiaNo ratings yet

- Kunci Jawaban Bahasa Inggris IdiomDocument2 pagesKunci Jawaban Bahasa Inggris IdiomTeguh RomdaniNo ratings yet

- #English 1 - #Welcome + #1 - Grammar BookDocument22 pages#English 1 - #Welcome + #1 - Grammar BookNatalia FligielNo ratings yet

- English Grammar: Unit 2: The Skeleton of The MessageDocument12 pagesEnglish Grammar: Unit 2: The Skeleton of The MessageAmeliaNo ratings yet

- 1.4 Adjectives: NounsDocument16 pages1.4 Adjectives: NounsLilibeth MalayaoNo ratings yet

- (Studies in Language Companion Series) Isabelle Bril-Clause Linking and Clause Hierarchy - Syntax and Pragmatics-John Benjamins Pub. Co (2010) PDFDocument644 pages(Studies in Language Companion Series) Isabelle Bril-Clause Linking and Clause Hierarchy - Syntax and Pragmatics-John Benjamins Pub. Co (2010) PDFankhwNo ratings yet

- Makalah Academic VocabularyDocument6 pagesMakalah Academic VocabularyAyu DiyasefiaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 26: ~는 것 Describing Nouns with VerbsDocument22 pagesLesson 26: ~는 것 Describing Nouns with VerbsBonaJSN [보나주소녀]No ratings yet

- Conditional-Sentences - Wish Time Clauses ADVANCEDDocument32 pagesConditional-Sentences - Wish Time Clauses ADVANCEDMiriam ChiovettaNo ratings yet

- How To Form Relative Clauses: A Girl Is Talking To Tom. Do You Know The Girl?Document4 pagesHow To Form Relative Clauses: A Girl Is Talking To Tom. Do You Know The Girl?WK LamNo ratings yet

- Table of Pronoun (Advanced)Document2 pagesTable of Pronoun (Advanced)Younus MasoodNo ratings yet

- B+ Revised SyllabusDocument14 pagesB+ Revised SyllabusB pNo ratings yet

- Voice Active PassiveDocument16 pagesVoice Active Passivevansh aggarwalNo ratings yet

- What Is PunctuationDocument14 pagesWhat Is PunctuationpriyaNo ratings yet

- Oblique Case-Marking in Indo-Aryan Experiencer ConstructionsDocument17 pagesOblique Case-Marking in Indo-Aryan Experiencer Constructionsss SNo ratings yet

- English AssignmentDocument7 pagesEnglish AssignmentAwais aliNo ratings yet

- Ingles Nivel 1Document58 pagesIngles Nivel 1Alejandra Verónica Mac garryNo ratings yet

- Nepravilni Glagoli Engleski JezikDocument6 pagesNepravilni Glagoli Engleski JezikAlien Elf100% (1)

- Unit 11 - Parallel StructureDocument20 pagesUnit 11 - Parallel StructureMelissa LissaNo ratings yet

- New Close Up B2 Plus Teachers BookDocument176 pagesNew Close Up B2 Plus Teachers BookNatalia DosantosNo ratings yet

- Adjective Clause ExplanationDocument24 pagesAdjective Clause ExplanationRayhan Rosihan ArsyadNo ratings yet

- Persian Self-Taught (In Roman Characters)Document192 pagesPersian Self-Taught (In Roman Characters)Франк Ким100% (3)

- Relative Clause TestDocument2 pagesRelative Clause TestArif İsmailNo ratings yet

- Causative PassiveDocument2 pagesCausative PassiveKateryna TaylorNo ratings yet

- Advanced English Grammar On Verbals (Infinitive-Participle-Gerund)Document10 pagesAdvanced English Grammar On Verbals (Infinitive-Participle-Gerund)English Teacher ESL 영어교사, 英語教師, 英语教师, 英語の先生, Преподаватель английского языка, مدرس اللغة الإنجليزيةقوتابخانه ي زماني ئينكليزيNo ratings yet

- Irreg Vbs ListDocument6 pagesIrreg Vbs ListEnrique GautierNo ratings yet

- VERBOSDocument2 pagesVERBOSMarce VillalpandoNo ratings yet

- Examination Syllabus B1Document3 pagesExamination Syllabus B1Jason TehNo ratings yet

- Interface Between Syntax and MorphologyDocument5 pagesInterface Between Syntax and Morphologydesertfox27No ratings yet