Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Curious Case of Baby Manji

Uploaded by

Jonathan HardinCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Curious Case of Baby Manji

Uploaded by

Jonathan HardinCopyright:

Available Formats

The Curious Case of Baby Manji

When does a baby cease to be a bundle of joy and becomes a diplomatic nightmare, with

the Supreme Court having to intervene? Baby Manji's birth in July 2008 made headlines

and is possibly responsible for at least some of the amendments made in 2010 to the

India's Assisted Reproductive Technology (ART) (Regulation) Bill. As this issue's cover

story, IVF in India: The Story So Far... revisits this contentious debate, Baby Manji's

case is an epitome of what can go wrong.

Baby Manji's story starts out innocuously enough with a Japanese couple, both doctors

themselves, getting into a surrogacy contract with a young married woman in a small

town in Gujarat, through a gynecologist. In hindsight, a clause in the contract stating

that the husband would care for the child if the couple separated should have raised

concerns but went unnoticed at the time.

These facts of the case are common knowledge by now: created from the sperm of

orthopaedic surgeon Ikufumi Yamada, and an egg from an unknown (reportedly an

Indian or Nepali) woman, the embryo was implanted into the surrogate's womb who

carried the pregnancy to full term and gave birth to a healthy baby girl. But, by then, the

couple had separated and Baby Manji was both parentless and stateless, caught between

the legal systems of two countries!

The surrogacy contract itself was silent on parental responsibilities: of the two

contracting parents, the surrogate as well as the anonymous egg donor. While the

biological father wanted to claim the baby, he was prevented by a legal system which

had no provision for children born via surrogacy. After a prolonged legal battle, Ikufumi

Yamada's mother, (who had come to India to look after the child she considered her

grandchild, after her son's Indian visa expired,) left for Japan with Baby Manji, but not

before an NGO had accused the father of child trafficking.

Baby Manji was born well after the Indian Council for Medical Research had released

guidelines for ART clinics but since they were voluntary, they had no standing. Three

years after Baby Manji was born, there are still more questions than answers. The draft

ART Bill which is being examined by the Union Cabinet with the view of making it a law,

has made landmark suggestions with a view to streamlining the process.

But concerns do arise on the Indian government's thrust to 'streamline' assisted

reproduction. India's image as the 'surrogacy capital of the world' has spawned a

thriving industry, and the law of the market is that when demand is more, supply will

increase. Once it is made law, will the ART Bill simply be legalising what has been

dubbed as 'rent-a-womb' industry?

Of course, not having any law on this issue today seems to be the greater evil. Most

importantly, the law should protect the rights of children born via surrogacy by clearly

defining parental responsibilities as well as providing monetary support to the surrogate

child, should the parents back away from claiming the child due to divorce or any other

reasons. India has proved that we have the logistic and medical capacity to be a

preferred surrogacy destination, but now we have to prove our ethical and humane

capacity to protect the rights of future generations of the likes of Baby Manjis.

You might also like

- Wealth TaxDocument54 pagesWealth TaxJerin GeorgeNo ratings yet

- Baby Farming in IndiaDocument25 pagesBaby Farming in IndiaApoorva MishraNo ratings yet

- Advances in Extraction TechniquesDocument13 pagesAdvances in Extraction TechniquesashajangamNo ratings yet

- Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: Florian Daniel Zepf, Caroline Sarah Biskup, Martin Holtmann, & Kevin RunionsDocument17 pagesDisruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: Florian Daniel Zepf, Caroline Sarah Biskup, Martin Holtmann, & Kevin RunionsPtrc Lbr LpNo ratings yet

- Lab Test Results 7 2015Document3 pagesLab Test Results 7 2015Antzee Dancee0% (1)

- Abdominal UltrasoundDocument6 pagesAbdominal Ultrasounds0800841739100% (1)

- CS HF Directory 2018 Print PDFDocument80 pagesCS HF Directory 2018 Print PDFAt Day's WardNo ratings yet

- Ozone Therapy in DentistryDocument16 pagesOzone Therapy in Dentistryshreya das100% (1)

- Ifrs Issues Solutions For PharmaDocument109 pagesIfrs Issues Solutions For PharmaSrinivasa Rao100% (1)

- Practical MCQ Question For 4-YearDocument39 pagesPractical MCQ Question For 4-Yearkhuzaima9100% (2)

- Delegated LegislationDocument20 pagesDelegated LegislationAmit Singh100% (5)

- 400 - Baby Manji Yamada Case Analysis - Krutika DudharejiyaDocument12 pages400 - Baby Manji Yamada Case Analysis - Krutika DudharejiyaSatish PatelNo ratings yet

- Bio-Medical Waste ManagementDocument36 pagesBio-Medical Waste Managementlyfzcool892097100% (6)

- Manage Odontogenic Infections Stages Severity AntibioticsDocument50 pagesManage Odontogenic Infections Stages Severity AntibioticsBunga Erlita RosaliaNo ratings yet

- Embryology GenitalDocument53 pagesEmbryology GenitalDhonat Flash100% (1)

- Surrogate Mother-A Commodity For Infertile Parents-Manu GuptaDocument11 pagesSurrogate Mother-A Commodity For Infertile Parents-Manu GuptaManu GuptaNo ratings yet

- Baby Manjhi Case StudyDocument1 pageBaby Manjhi Case StudyLaksh Arora100% (2)

- Commercial Surrogacy Case Sparks Legal CrisisDocument11 pagesCommercial Surrogacy Case Sparks Legal Crisissonam1992No ratings yet

- Commercialization of Surrogacy in India & Its Legal Context: A Critical Study With Regard To Baby Manji Yamda'S Case Shabeer Ali.H DR - Asha SundaramDocument20 pagesCommercialization of Surrogacy in India & Its Legal Context: A Critical Study With Regard To Baby Manji Yamda'S Case Shabeer Ali.H DR - Asha SundaramShabeer AliNo ratings yet

- MLC Right To PrivacyDocument8 pagesMLC Right To PrivacySweta MishraNo ratings yet

- Commercial Surrogacy: Is It Morally and Ethically Acceptable in India?Document4 pagesCommercial Surrogacy: Is It Morally and Ethically Acceptable in India?arun bhattaNo ratings yet

- Surrogarcy in IndiaDocument3 pagesSurrogarcy in IndiaPp SsNo ratings yet

- Regulations needed for surrogacy in IndiaDocument5 pagesRegulations needed for surrogacy in IndiaNarendra MetreNo ratings yet

- 15d72016 AIJJS - 77-88Document12 pages15d72016 AIJJS - 77-88Amogh SanikopNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy BillDocument2 pagesSurrogacy BillVasundhara SaxenaNo ratings yet

- The First Chart Depicts The Success Rate With Fresh Surrogacy Cycles Where Donor Eggs Were UsedDocument7 pagesThe First Chart Depicts The Success Rate With Fresh Surrogacy Cycles Where Donor Eggs Were Usedswam_rajNo ratings yet

- Submitted By: Prieya Ahluwalia 3-A, 35417703819 Submitted To: Prof. Neeru NakraDocument25 pagesSubmitted By: Prieya Ahluwalia 3-A, 35417703819 Submitted To: Prof. Neeru NakraPRIEYA AHLUWALIA100% (1)

- Surrogacy BillDocument16 pagesSurrogacy Billayushi pandeyNo ratings yet

- Legal Aspect For Surrogacy IndiaDocument11 pagesLegal Aspect For Surrogacy IndiaIvfSurrogacyNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy Laws in IndiaDocument20 pagesSurrogacy Laws in IndiaSUDHIR'S PHOTOGRAPHYNo ratings yet

- MumalDocument17 pagesMumalNidhi PiousNo ratings yet

- July 2015 1436858446 53 PDFDocument2 pagesJuly 2015 1436858446 53 PDFAnkit Sourav SahooNo ratings yet

- Baby Ramji PDFDocument130 pagesBaby Ramji PDFMadhumitaNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal On Evolution of Surrogacy LawsDocument11 pagesResearch Proposal On Evolution of Surrogacy LawsAbhay GuptaNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy: Presented By: Neha IslamDocument27 pagesSurrogacy: Presented By: Neha IslamShaaz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Varun Goswami & Sanjana Shrivastav - TNNLU National Essay Writing CompetitionDocument15 pagesVarun Goswami & Sanjana Shrivastav - TNNLU National Essay Writing Competitiontanish aminNo ratings yet

- SurrogacyDocument7 pagesSurrogacyaditiNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy Under Indian LawDocument9 pagesSurrogacy Under Indian LawshinchanNo ratings yet

- A Critical Insights Regarding Laws of Surrogacy in IndiaDocument9 pagesA Critical Insights Regarding Laws of Surrogacy in Indiakhyathi priyaNo ratings yet

- Rights of Children and Need for Surrogacy LawsDocument6 pagesRights of Children and Need for Surrogacy LawsPranzalNo ratings yet

- The-Issues-Surrounding-It/: Constitutional ProvisionDocument3 pagesThe-Issues-Surrounding-It/: Constitutional ProvisionRajat KashyapNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy in India: A Critical Appraisal: BackgroundDocument3 pagesSurrogacy in India: A Critical Appraisal: BackgroundSmriti SharmaNo ratings yet

- Indian Surrogacy Bill Bans Commercial SurrogacyDocument11 pagesIndian Surrogacy Bill Bans Commercial SurrogacyIshita AgarwalNo ratings yet

- Case Law On SurrogacyDocument6 pagesCase Law On SurrogacyYash JainNo ratings yet

- Case Law On SurrogacyDocument6 pagesCase Law On SurrogacyYash JainNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy in IndiaDocument14 pagesSurrogacy in IndiaIshita RaiNo ratings yet

- Case Analysis Comparision - Baby M Manji-1Document26 pagesCase Analysis Comparision - Baby M Manji-1api-372898116No ratings yet

- Commercial Surrogacy in IndiaDocument1 pageCommercial Surrogacy in IndiaJuhi bohraNo ratings yet

- Pros and Cons of Surrogacy in IndiaDocument4 pagesPros and Cons of Surrogacy in IndiaAnkita ThakurNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Surrogacy Bill 2016: Constitutional Boundaries and ParametersDocument12 pagesAn Analysis of Surrogacy Bill 2016: Constitutional Boundaries and ParametersRajat KashyapNo ratings yet

- India SurrogacyDocument5 pagesIndia Surrogacystyzox.comNo ratings yet

- Submitted By: Raman Deep (M.Phil. Sociology) Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University, Delhi (India)Document7 pagesSubmitted By: Raman Deep (M.Phil. Sociology) Delhi School of Economics, Delhi University, Delhi (India)Jaya PriyaNo ratings yet

- Socio-Legal Challenges of Surrogacy in IndiaDocument5 pagesSocio-Legal Challenges of Surrogacy in IndiaSatyam PathakNo ratings yet

- SurrogasyDocument29 pagesSurrogasyArshi KhanNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy and Conflicting Interests of Parties of Surrogacy Arrangements in India: An InsightDocument20 pagesSurrogacy and Conflicting Interests of Parties of Surrogacy Arrangements in India: An InsightSneha SolankiNo ratings yet

- Critical analysis of India's Surrogacy BillDocument17 pagesCritical analysis of India's Surrogacy BillMRINMAY KUSHALNo ratings yet

- Regulated Re-Instatement of Commercial Surrogacy in IndiaDocument11 pagesRegulated Re-Instatement of Commercial Surrogacy in IndiaAmogh SanikopNo ratings yet

- Health Law AssignmentDocument3 pagesHealth Law Assignmentkhushbu guptaNo ratings yet

- CVVVVV VVVVV VV VVVVDocument4 pagesCVVVVV VVVVV VV VVVVKrizzle ApostolNo ratings yet

- Manji Yamada V/s Union of India (UOI) and Anr.Document6 pagesManji Yamada V/s Union of India (UOI) and Anr.DimpleChainaniNo ratings yet

- Submission of Assignment Towards Fulfilment For Assessment of CA-III in The Subject of Family Law - IDocument11 pagesSubmission of Assignment Towards Fulfilment For Assessment of CA-III in The Subject of Family Law - IDhruv ThakurNo ratings yet

- Serrogate Mother - Id.enDocument7 pagesSerrogate Mother - Id.enAndikNo ratings yet

- LRW Sem 1 Asg 2Document10 pagesLRW Sem 1 Asg 2Krishna devineNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy and Indian LawDocument4 pagesSurrogacy and Indian LawShreyNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy in IndiaDocument15 pagesSurrogacy in Indiaamritam yadavNo ratings yet

- Critical Study of The Surrogacy Bill 2016Document5 pagesCritical Study of The Surrogacy Bill 2016Srijesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Piyali Mitra - CONTENT SUBMISSION (Looking at Female Foeticide Through The Lens of Human Rights, Society and Law)Document4 pagesPiyali Mitra - CONTENT SUBMISSION (Looking at Female Foeticide Through The Lens of Human Rights, Society and Law)Piyali MitraNo ratings yet

- Requisite Fitter Regulations for India's Commercial SurrogacyDocument1 pageRequisite Fitter Regulations for India's Commercial SurrogacyTannya BrahmeNo ratings yet

- Rajiv Gandhi National University of Law: Final Draft Concept of SurrogacyDocument19 pagesRajiv Gandhi National University of Law: Final Draft Concept of Surrogacy19140 VATSAL DHARNo ratings yet

- Assignment - 2 Family Law - 1 Surrogacy: Submitted By: Mayank Kashyap Roll No. - 04013403820 Class - 2nd Year (A) BA LLBDocument9 pagesAssignment - 2 Family Law - 1 Surrogacy: Submitted By: Mayank Kashyap Roll No. - 04013403820 Class - 2nd Year (A) BA LLBMayank KashyapNo ratings yet

- Name SID Charanjit Singh Arshpreet Singh Akshdeep Singh Sanket Hatinderpal Singh Ghotra Parampreet SinghDocument35 pagesName SID Charanjit Singh Arshpreet Singh Akshdeep Singh Sanket Hatinderpal Singh Ghotra Parampreet SinghVarunKantNo ratings yet

- Comparative laws on surrogacyDocument3 pagesComparative laws on surrogacyShaikh ZeeshanNo ratings yet

- CandidateHandbook2014 19032014Document377 pagesCandidateHandbook2014 19032014Jonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Kaliyaperumal and AnrDocument7 pagesKaliyaperumal and AnrJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Nuisance 2Document13 pagesNuisance 2Jonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Archaelogical SourcesDocument22 pagesArchaelogical SourcesJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- BMWDocument6 pagesBMWJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Syllabus History TybaDocument4 pagesSyllabus History TybaJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- ChapterDocument12 pagesChapterJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy India For AllDocument9 pagesSurrogacy India For All24x7emarketingNo ratings yet

- Legal Aid Scheme Was First Introduced by Justice PDocument19 pagesLegal Aid Scheme Was First Introduced by Justice PJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Indian Economy - From EgyankoshDocument15 pagesIndian Economy - From Egyankoshrajender100No ratings yet

- Admin ReformDocument47 pagesAdmin ReformJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1917290Document16 pagesSSRN Id1917290Jonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- New Text DocumentDocument1 pageNew Text DocumentJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Service TaxDocument21 pagesService TaxJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Kaliyaperumal and AnrDocument7 pagesKaliyaperumal and AnrJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Syllabus History TybaDocument4 pagesSyllabus History TybaJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- New Text DocumentDocument1 pageNew Text DocumentJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Radiological & Imaging Association vs. UoI & OrsDocument32 pagesRadiological & Imaging Association vs. UoI & OrsJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- R To DevelopmentDocument23 pagesR To DevelopmentJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Curb Female FoeticideDocument12 pagesCurb Female FoeticideLive LawNo ratings yet

- 498ADocument24 pages498AJonathan Hardin100% (1)

- DrowningDocument10 pagesDrowningadesamboraNo ratings yet

- Bonded LaborDocument19 pagesBonded LaborVijay Kumar SodadasNo ratings yet

- IntoxicationDocument5 pagesIntoxicationJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- 321c4financial Marketing SyllabusDocument3 pages321c4financial Marketing SyllabusJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- Cehat Vs Union of IndiaDocument11 pagesCehat Vs Union of IndiaJonathan HardinNo ratings yet

- A Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen PlanusDocument1 pageA Novel Visual Clue For The Diagnosis of Hypertrophic Lichen Planus600WPMPONo ratings yet

- Low Back Pain in Elderly AgeingDocument29 pagesLow Back Pain in Elderly AgeingJane ChaterineNo ratings yet

- MYMAN Chanchinbu Issue No. 5Document6 pagesMYMAN Chanchinbu Issue No. 5Langa1971No ratings yet

- 2017-18 Undergraduate Catalog PDFDocument843 pages2017-18 Undergraduate Catalog PDFguruyasNo ratings yet

- Local Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity AlgorithmDocument1 pageLocal Anesthetic Systemic Toxicity AlgorithmSydney JenningsNo ratings yet

- Endocrine Exam ReviewDocument2 pagesEndocrine Exam Reviewrockforj3susNo ratings yet

- Arichuvadi Maruthuva Malar 2nd IssueDocument52 pagesArichuvadi Maruthuva Malar 2nd IssueVetrivel.K.BNo ratings yet

- 4 Levels of Perio DZDocument2 pages4 Levels of Perio DZKIH 20162017No ratings yet

- TEMPLATE-B-Master-list-of-Learners-for-the-Pilot-Implementation-of-F2F-Classes-for-S.Y.-2021-2022Document7 pagesTEMPLATE-B-Master-list-of-Learners-for-the-Pilot-Implementation-of-F2F-Classes-for-S.Y.-2021-2022Resa Consigna MagusaraNo ratings yet

- Effects of Pulmonary Rehabilitation On Physiologic and Psychosocial Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument10 pagesEffects of Pulmonary Rehabilitation On Physiologic and Psychosocial Outcomes in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseElita Urrutia CarrilloNo ratings yet

- LSM RepairDocument4 pagesLSM RepairDanily Faith VillarNo ratings yet

- Who Trs 999 FinalDocument292 pagesWho Trs 999 FinalfmeketeNo ratings yet

- Material Safety Data Sheet: Tert-Amyl Alcohol MSDSDocument6 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet: Tert-Amyl Alcohol MSDSmicaziv4786No ratings yet

- Mental Health Personal Statement - Docx'Document2 pagesMental Health Personal Statement - Docx'delson2206No ratings yet

- Tilapia 4Document69 pagesTilapia 4Annisa MeilaniNo ratings yet

- JC Oncology55211005Document32 pagesJC Oncology55211005Neenuch ManeenuchNo ratings yet

- The Functions and Types of AntibioticsDocument3 pagesThe Functions and Types of AntibioticsFida TsabitaNo ratings yet

- The Ethics of Medical Marijuana Government Restrictions vs. Medical Necessity - An UpdateDocument12 pagesThe Ethics of Medical Marijuana Government Restrictions vs. Medical Necessity - An UpdateAle PicadoNo ratings yet

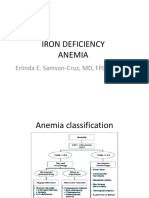

- Iron Deficiency Anemia and Megaloblastic Anemia - Samson-Cruz MDDocument47 pagesIron Deficiency Anemia and Megaloblastic Anemia - Samson-Cruz MDMiguel Cuevas DolotNo ratings yet