Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Hpylori

Uploaded by

carlosvalxOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Hpylori

Uploaded by

carlosvalxCopyright:

Available Formats

Articles

14-day triple, 5-day concomitant, and 10-day sequential

therapies for Helicobacter pylori infection in seven Latin

American sites: a randomised trial

E Robert Greenberg, Garnet L Anderson, Douglas R Morgan, Javier Torres, William D Chey, Luis Eduardo Bravo, Ricardo L Dominguez,

Catterina Ferreccio, Rolando Herrero, Eduardo C Lazcano-Ponce, Mara Mercedes Meza-Montenegro, Rodolfo Pea, Edgar M Pea,

Eduardo Salazar-Martnez, Pelayo Correa, Mara Elena Martnez, Manuel Valdivieso, Gary E Goodman, John J Crowley, Laurence H Baker

Summary

Background Evidence from Europe, Asia, and North America suggests that standard three-drug regimens of a protonpump inhibitor plus amoxicillin and clarithromycin are significantly less effective for eradication of Helicobacter pylori

infection than are 5-day concomitant and 10-day sequential four-drug regimens that include a nitroimidazole. These

four-drug regimens also entail fewer antibiotic doses than do three-drug regimens and thus could be suitable for

eradication programmes in low-resource settings. Few studies in Latin America have been done, where the burden of

H pylori-associated diseases is high. We therefore did a randomised trial in Latin America comparing the effectiveness

of four-drug regimens given concomitantly or sequentially with that of a standard 14-day regimen of triple therapy.

Methods Between September, 2009, and June, 2010, we did a randomised trial of empiric 14-day triple, 5-day

concomitant, and 10-day sequential therapies for H pylori in seven Latin American sites: Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica,

Honduras, Nicaragua, and Mexico (two sites). Participants aged 2165 years who tested positive for H pylori by a urea

breath test were randomly assigned by a central computer using a dynamic balancing procedure to: 14 days of

lansoprazole, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin (standard therapy); 5 days of lansoprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin,

and metronidazole (concomitant therapy); or 5 days of lansoprazole and amoxicillin followed by 5 days of lansoprazole,

clarithromycin, and metronidazole (sequential therapy). Eradication was assessed by urea breath test 68 weeks after

randomisation. The trial was not masked. Our primary outcome was probablity of H pylori eradication. Our analysis

was by intention to treat. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, registration number NCT01061437.

Findings 1463 participants aged 2165 years were randomly allocated a treatment: 488 were treated with 14-day

standard therapy, 489 with 5-day concomitant therapy, and 486 with 10-day sequential therapy. The probability of

eradication with standard therapy was 822% (401 of 488), which was 86% higher (95% adjusted CI 26145) than

with concomitant therapy (736% [360 of 489]) and 56% higher (004% to 116) than with sequential therapy

(765% [372 of 486]). Neither four-drug regimen was significantly better than standard triple therapy in any of the

seven sites.

Interpretation Standard 14-day triple-drug therapy is preferable to 5-day concomitant or 10-day sequential four-drug

regimens as empiric therapy for H pylori infection in diverse Latin American populations.

Funding Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, US National Institutes of Health.

Introduction

Helicobacter pylori infects most of the worlds adult

population and is the principal cause of gastric cancer,

accounting for an estimated 60% of all cases.13 Gastric

cancer is second only to lung cancer as a cause of cancer

death worldwide, and almost all of the nearly 1 million

cases and 075 million deaths each year occur in east

Asia and Latin America.4 Although gastric cancer death

rates have fallen in recent decades, the number of deaths

has actually increased as a consequence of ageing

populations, and gastric cancer is projected to rank

among the ten leading global causes of death by 2030.5,6

H pylori is also the main cause of peptic ulcer disease,

which accounts for the loss of about 46 million disabilityadjusted life-years every year worldwide, with most

of the burden borne by populations in low-income and

middle-income countries.7 Population-wide eradication

programmes seem to offer the most direct approach to

reducing the enormous human and economic con

sequences of H pylori infection; however, none has been

implemented to date.8

Large programmes for H pylori eradication require a

practical and inexpensive antibiotic regimen that is

effective in the specific locale where it will be used.

Standard antibiotic regimens for H pylori usually entail a

proton-pump inhibitor, amoxicillin, and clarithromycin,

taken together over 714 days.911 However, the effective

ness of these triple-therapy regimens seems to have

diminished over time, largely as a result of emerging

resistance of the organism to clarithromycin.12,13 Recent

meta-analyses have shown that regimens that add a

nitroimidazole (metronidazole or tinidazole) to triple

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8

Published Online

July 20, 2011

DOI:10.1016/S01406736(11)60825-8

See Online/Comment

DOI:10.1016/S01406736(11)61099-4

SWOG Statistical Center, Cancer

Research and Biostatistics,

Seattle, WA, USA

(E R Greenberg MD,

G L Anderson PhD,

J J Crowley PhD); Division of

Public Health Sciences, Fred

Hutchinson Cancer Research

Center, Seattle, WA, USA

(E R Greenberg, G L Anderson,

G E Goodman MD); Division of

Gastroenterology, University

of North Carolina, Chapel Hill,

NC, USA (D R Morgan MD);

Unidad de Investigacin en

Enfermedades Infecciosas,

Instituto Mexicano del Seguro

Social, Mexico City, Mexico

(J Torres PhD); Division of

Gastroenterology, University

of Michigan Medical School,

Ann Arbor, MI, USA

(W D Chey MD); Departamento

de Patologa, Universidad

del Valle, Cali, Colombia

(L E Bravo MD); Hospital

Regional de Occidente, Santa

Rosa de Copn, Honduras

(R L Dominguez MD);

Departamento de Salud

Pblica, Pontificia Universidad

Catlica de Chile, Santiago,

Chile (C Ferreccio MD);

Fundacin INCIENSA, San Jos,

Costa Rica (R Herrero MD);

Screening and Prevention

Group, International Agency

for Research on Cancer, World

Health Organization, Lyon,

France (R Herrero); Instituto

Nacional de Salud Pblica,

Cuernavaca, Mexico

(E C Lazcano-Ponce MD,

E Salazar-Martnez PhD);

Instituto Tecnolgico de

Sonora, Ciudad Obregn,

Mexico

(M M Meza-Montenegro PhD);

Centro de Investigacin en

Demografa y Salud, Len,

Articles

Nicaragua (R Pea PhD,

E M Pea MD); Division of

Gastroenterology, Vanderbilt

Medical Center, Nashville, TN,

USA (P Correa MD); Cancer

Prevention and Control,

University of Arizona Cancer

Center, Tuscon, AZ, USA

(M E Martnez PhD); Division of

Hematology/Oncology,

University of Michigan Medical

School, Ann Arbor, MI, USA

(M Valdivieso MD, L H Baker DO);

and Swedish Cancer Institute,

Seattle, WA, USA

(G E Goodman)

Correspondence to:

Dr E Robert Greenberg, Cancer

Research and Biostatistics,

1730 Minor Ave, Suite 1900,

Seattle, WA, USA 981011468

e.r.greenberg@dartmouth.edu

For more on the

Rome III diagnostic

questionnaire see http://

www.theromefoundation.org

therapy and are given either sequentially for 10 days or

concomitantly for 5 days are significantly more successful

at eradication of H pylori infection than are triple-therapy

regimens.1416 These regimens also require fewer doses of

antibiotics and thus might be more affordable in lowresource settings. Almost all the evidence supporting

these four-drug regimens comes from Europe and Asia;

few data are available from Latin America, a region with

some of the worlds highest rates of gastric cancer

mortality.17 We therefore undertook a randomised trial in

Latin America comparing the effectiveness of four-drug

regimens given concomitantly or sequentially with that

of a standard 14-day regimen of triple therapy. The trial

also provided insights into the feasibility of communitybased programmes of H pylori eradication.

Methods

Study design and patients

The trial (SWOG S0701) was a randomised trial of empiric

14-day triple, 5-day concomitant, and 10-day sequential

therapies for H pylori infection in seven Latin American

sites: Chile (Santiago), Colombia (Tquerres), Costa Rica

(Guanacaste), Honduras (Santa Rosa de Copn), Mexico

(Ciudad Obregn and Tapachula), and Nicaragua (Len).

Between September, 2009, and June, 2010, study research

staff recruited potential participants from the general

population of adult men and women aged 2165 years

and explained the purpose and eligibility requirements

of the study to them. Staff in Colombia, Costa Rica, and

Nicaragua selected individuals from a census of

households, in Chile they selected potential participants

from a list of individuals served by a large public primary

1859 assessed for eligibility

390 excluded

375 UBT negative

8 UBT positive, ineligible

7 withdrew consent

before UBT

1469 randomised

6 excluded because of data

entry errors

488 allocated to standard therapy

489 allocated to concomitant therapy

486 allocated to sequential therapy

488 analysed

475 valid follow-up UBTs

13 missing or invalid

follow-up UBTs

11 withdrew consent or

refused treatment

2 unable to contact

489 analysed

471 valid follow-up UBTs

18 missing or invalid

follow-up UBTs

12 withdrew consent or

refused treatment

5 unable to contact

1 too ill to return

486 analysed

468 valid follow-up UBTs

18 missing or invalid

follow-up UBTs

13 withdrew consent or

refused treatment

2 inconclusive UBTs

3 unable to contact

Figure: Trial profile

UBT=urea breath test.

care clinic, and in Honduras and Mexico (two sites) they

recruited participants by walking house-to-house within

the local community or through announcements at

primary care clinics.

Study participants in Tapachula (Mexico), Nicaragua,

and Chile were predominantly urban, and those in the

other sites were from small, rural communities.

Potential participants were deemed ineligible if they

had been treated in the past for H pylori infection, had

serious illnesses that might end their lives before

completing the study, or had other disorders that

required or precluded treatment with antibiotics or

proton-pump inhibitors. They also had to agree to

abstain from alcohol use for at least 2 weeks. Those

who expressed an interest in participating and gave

signed, informed consent then completed an interview

regarding socioeconomic characteristics and health

history and a detailed gastrointestinal-symptom-history

assessment with the validated Spanish language version

of the Rome III diagnostic questionnaire for the adult

functional gastrointestinal disorders.18,19 The institu

tional review boards for each clinical centre and for the

SWOG Statistical Center, Seattle, WA, USA approved

the study protocol.

Procedures

Participants provided a urea breath test for H pylori

infection by exhaling into foil balloons before, and 30 min

after, consuming a 75 mg dose of C-labelled urea with

water. Staff at each centre analysed the breath samples

using an infrared mass spectrometry device (IRIS,

Wagner Analysen Technik, Bremen, Germany) that

produced a computer-generated result of positive (change

relative to baseline 40%) or negative (change relative to

baseline <25%); intermediate values were classified as

inconclusive. If a participant reported use of an antibiotic

or proton-pump inhibitor within the past 15 days, or if

the result from the urea breath test was inconclusive, the

test was rescheduled for a later date.

Study staff contacted participants at least once during

treatment to encourage adherence and to remind them

to return any unused doses at their follow-up visit, which

was scheduled to occur 68 weeks after randomisation.

During follow-up visits, participants completed another

interview assessing adherence to therapy, their reasons

for missing any doses of the regimens, and the occurrence

of any new or worsened medical disorders that led them

to seek medical attention. Study staff counted the number

of drug doses returned and administered the follow-up

urea breath test.

Randomisation and masking

Participants who had a positive urea breath test and met

all other eligibility criteria were randomly assigned, in

equal proportions, to one of three treatment groups:

standard triple therapy of lansoprazole 30 mg, amoxicillin

1000 mg, and clarithromycin 500 mg taken twice a day for

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8

Articles

14 days; concomitant therapy of lansoprazole 30 mg,

amoxicillin 1000 mg, clarithromycin 500 mg, and

metronidazole 500 mg taken twice a day for 5 days; or

sequential therapy of lansoprazole 30 mg and amoxicillin

1000 mg taken twice a day for 5 days followed by

lansoprazole 30 mg, clarithromycin 500 mg, and

metronidazole 500 mg taken twice a day for 5 days. Each

clinical centre purchased its own supply of the drugs, as

generic (off-patent) preparations, from suppliers in

country, except the centres in Honduras and Nicaragua,

which both used the same supplier in Honduras. The

drug suppliers provided quality-control data for the

content and dissolution of each drug. Randomisation was

implemented centrally through a dynamic balancing

procedure at the SWOG Statistical Center to ensure

balance within centre by age and sex across the three

regimens. Staff at the clinical centres entered data for

potentially-eligible, consented individuals into the SWOG

Statistical Center computer using a web-based data entry

system. If the participants met all eligibility requirements,

the computer assigned them to a treatment group and

immediately transmitted the treatment assignment to the

clinical centre. All participants were randomly assigned in

a 1:1:1 ratio within 2 weeks after a positive urea-breath-test

result. The trial was not masked.

Statistical analysis

We designed the study to address two primary hypotheses.

The first hypothesis was that 5-day concomitant therapy

was not inferior to 14-day standard therapy, whereby

inferiority was defined as a difference in eradication

probability of 5% or greater in favour of standard therapy.

We reasoned that the shorter duration and lower cost

associated with concomitant therapy would make it

preferable to standard therapy if it were not appreciably

less effective in eradication of H pylori infection. Our

second hypothesis was that 10-day sequential therapy

would be more effective than 14-day standard therapy,

because a four-drug sequential regimen would be

preferred over standard three-drug therapy only if it were

clearly superior in eradication of H pylori infection.

Assuming an eradication rate of 80% for standard

therapy, 10% missing follow-up urea-breath-test results,

and 210 randomised participants per centre (1470 total),

each treatment group comparison would have 82% power

to detect a difference of 8% or greater, based on a twosided, 0025-level test. Although a meta-analysis by Essa

and colleagues16 suggested that concomitant therapy was

about 10% better than sequential therapy, if the therapies

were actually equivalent the trial would have 46% power

to reject the inferiority of concomitant therapy, based on

a one-sided, 0025-level test.

Our primary statistical analyses adhered to the

intention-to-treat principle and included all randomised

eligible participants, with those without a definitive

follow-up urea breath test judged to be treatment failures

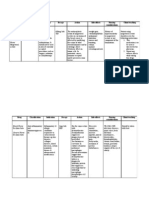

(urea-breath-test positive). To compare concomitant

5-day

14-day

concomitant

standard

therapy (N=488) therapy (N=489)

10-day

sequential

therapy (N=486)

Total

(N=1463)

Centre

Santiago (Chile)

69 (14%)

70 (14%)

70 (14%)

Tquerres (Colombia)

71 (15%)

72 (15%)

69 (14%)

209 (14%)

212 (15%)

Guanacaste (Costa Rica)

70 (14%)

70 (14%)

70 (14%)

210 (14%)

Copn (Honduras)

70 (14%)

72 (15%)

71 (15%)

213 (15%)

Tapachula (Mxico)

71 (15%)

69 (14%)

70 (14%)

210 (14%)

Obregn (Mxico)

70 (14%)

69 (14%)

71 (15%)

210 (14%)

Len (Nicaragua)

67 (14%)

67 (14%)

65 (13%)

199 (14%)

Women

287 (59%)

288 (60%)

286 (59%)

861 (59%)

Men

201 (41%)

201 (41%)

200 (41%)

602 (41%)

Sex

Age (years)

2029

66 (14%)

66 (14%)

91 (19%)

223 (15%)

3039

137 (28%)

139 (28%)

117 (24%)

393 (27%)

4049

142 (29%)

117 (24%)

127 (26%)

386 (26%)

50

143 (29%)

167 (34%)

151 (31%)

461 (32%)

Years of education

4

88 (18%)

77 (16%)

80 (17%)

245 (17%)

58

135 (28%)

166 (34%)

143 (29%)

444 (30%)

912

146 (30%)

135 (28%)

136 (28%)

417 (29%)

13

71 (15%)

71 (15%)

70 (14%)

212 (14%)

Not reported

48 (10%)

40 (8%)

57 (12%)

145 (10%)

Chronic dyspeptic symptoms

Present

125 (26%)

121 (25%)

127 (26%)

373 (26%)

Absent

363 (74%)

368 (75%)

359 (74%)

1090 (75%)

Data are n (%).

Table 1: Participant characteristics by treatment group

Standard

therapy (N=475)

Concomitant

therapy (N=471)

Sequential

therapy (N=470)

Total

(N=1416*)

427 (90%)

442 (94%)

437 (93%)

1306 (92%)

7 (2%)

0 (0)

Most (5080%)

24 (5%)

14 (3%)

Less than half (<50%)

Amount of drugs taken

All (100%)

Nearly all (>80%)

2 (<1%)

21 (4%)

9 (<1%)

59 (4%)

10 (2%)

8 (2%)

5 (11%)

23 (2%)

Undetermined (but not all)

7 (2%)

5 (1%)

5 (1%)

17 (1%)

None

0 (0)

2 (<1%)

0 (0)

2 (<1%)

Reasons for not taking all drugs

Concern about having or

developing side-effects

Unrelated illness or injury

Forgot or inconvenient

Reason not given

41 (9%)

3 (1%)

36 (8%)

0 (0)

28 (6%)

1 (<1%)

25 (5%)

3 (<1%)

33 (7%)

5 (1%)

37 (8%)

2 (<1%)

102 (7%)

9 (<1%)

98 (7%)

5 (<1%)

Data are n (%). *Includes 1414 participants with a valid follow-up urea breath test and two (from the sequential

therapy group) whose urea breath test results were inconclusive. Based on count of returned drugs and self-report

among participants who returned for a follow-up urea breath test. Multiple responses allowed.

Table 2: Adherence to treatment of patients that returned for 6-week follow-up, by treatment group

versus standard therapy, we used a two-sample Z test of

the null hypothesis, in which the difference in the

estimated probabilities of eradication was 5% or greater

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8

Articles

in favour of the standard regimen, based on a one-sided

test of non-inferiority. Comparison of sequential versus

standard therapies was based on a two-sample Z test for

no difference between eradication probabilities. Sensi

tivity to missing data assumptions was examined by

N

Helicobacter pylori

eradication

Difference from standard group

(adjusted 95% CI for difference)

14-day standard therapy

488

401 (822% [785 to 855])

5-day concomitant therapy

489

360 (736% [695 to 775])

86% (26 to 145)

10-day sequential therapy

486

372 (765% [725 to 802])

56% (04 to 116)

Intention to treat (N= 1463)

Definitive 6-week UBT (N=1414)

14-day standard therapy

475

401 (844% [808 to 876])

5-day concomitant therapy

471

360 (764% [723 to 802])

80% (22 to 137)

10-day sequential therapy

468

372 (794% [755 to 831])

49% (09 to 108)

Adherent to therapy (N=1314)

14-day standard therapy

434

378 (871% [836 to 901])

5-day concomitant therapy

442

348 (787% [746 to 825])

84% (27 to 140)

10-day sequential therapy

438

355 (811% [771 to 846])

60% (03 to 118)

Data are number (% [95% CI]) unless otherwise indicated. UBT=urea breath test.

Table 3: Helicobacter pylori eradication by treatment group for three definitions of analysis population

N

Sex

Women

14-day standard

Helicobacter pylori

eradication

Difference from standard p value for

group (adjusted 95% CI) interaction*

861

287

234 (815%)

091

5-day concomitant

288

207 (719%)

97% (18 to 175)

10-day sequential

286

214 (748%)

67% (14 to 148)

Men

602

14-day standard

201

167 (831%)

201

153 (761%)

70% (20 to 159)

10-day sequential

200

158 (790%)

41% (52 to 133)

Age

2140 years

663

021

14-day standard

222

5-day concomitant

220

164 (745%)

74% (13 to 162)

10-day sequential

221

160 (724%)

96% (03 to 189)

4165 years

800

182 (820%)

14-day standard

266

219 (823%)

5-day concomitant

269

196 (729%)

95% (14 to 175)

10-day sequential

265

212 (800%)

23% (56 to 103)

Chronic dyspeptic symptoms

Absent

1090

363

5-day concomitant

368

277 (753%)

65% (02 to 133)

10-day sequential

359

281 (783%)

35% (34 to 105)

Present

14-day standard

373

297 (818%)

038

14-day standard

125

104 (832%)

5-day concomitant

121

83 (686%)

146% (25 to 267)

10-day sequential

127

91 (717%)

115% (09 to 240)

(Continues on next page)

Role of the funding source

The sponsors of the study had no role in study design,

data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or

writing of the report. All authors had full access to the

data in the study and participated in the decision to

submit for publication.

Results

5-day concomitant

excluding data from participants without a conclusive

follow-up urea breath test. To establish how poor

adherence could have affected our conclusions, we

further restricted the analyses to participants with a

definitive urea breath test who had taken at least 80% of

their assigned study drugs.

Secondary analyses assessed variability in treatment

outcome by sex, age, presence of chronic dyspeptic

symptoms, and clinical centre. Tests of interaction were

calculated as deviance tests comparing logistic regression

models with the treatment group indicators, the

designated covariate, and their interaction terms, with

those without the interaction terms.

All analyses were done with SAS version 9.2 and

R version 2.12.2 statistical software. Bonferroni-adjusted

95% CIs were used to account for the two primary

comparisons, and p values less than 0025 were classed

as statistically significant. No corrections for multiplicity

were applied to secondary analyses, because they were

considered to be exploratory. All p values were twosided except the test of non-inferiority.

This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, regis

tration number NCT01061437.

1859 potentially-eligible adults agreed to participate in the

study and completed the screening interview and intake

questionnaire, but seven withdrew before the urea breath

test (figure). The test was positive for 1471 (79%) of

1852 tested participants. Eight patients with a positive test

were not randomly assigned because they opted not to be

treated, could not be randomly assigned within 2 weeks of

their urea breath test, or had a disqualifying factor

(eg, pregnancy). Six participants with a negative urea

breath test, who were randomly assigned incorrectly

because of data entry errors, were withdrawn from the

study before receiving treatment, and their data were not

included in any of the following analyses. Of the eligible

participants who were randomised, 861 (59%) of 1463 were

women, 847 (58%) of 1463 were age 40 years or older, and

373 (25%) of 1463 had chronic dyspeptic symptoms as

classified by the Rome III criteria. Participant characteristics

were balanced between the three treatment groups (table 1).

47 participants did not return for their follow-up urea

breath test, and two participants had follow-up tests that

were inconclusive after two repeat tests. Thus, we obtained

definitive follow-up urea-breath-test results for 1414 (97%)

of 1463 of the randomised eligible participants (figure).

Table 2 shows adherence to treatment of patients

that returned for 6-week follow-up. 1313 (92%) of

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8

Articles

1416 participants who returned for their follow-up visit

had taken at least 80% of their assigned drugs, as

assessed by pill count and self-report (table 2). Five

participants had new, therapy-related symptoms

(stomach discomfort, nausea or vomiting, or fatigue or

weakness) that led them to seek medical attention; one

in the standard treatment group and two each in the

concomitant and sequential treatment groups.

In intention-to-treat analyses, the estimated probability

of H pylori eradication was higher with 14-day standard

triple therapy than with 5-day concomitant therapy and

10-day sequential therapy (table 3). The null hypothesis

of inferiority of concomitant therapy to standard therapy

could not be rejected (one-sided p=091); thus, the data

are consistent with 5-day concomitant therapy being

inferior to 14-day standard therapy. The difference

between 10-day sequential therapy and standard therapy

was not significant (p=004) at the p=0025 level, but the

near statistical significance of this two-sided test suggests

that sequential therapy was not as effective as standard

therapy. Sensitivity analyses that excluded participants

without a definitive follow-up urea breath test and those

that were confined to participants who had adhered to

the prescribed regimens showed similar patterns of

treatment contrasts as the intention-to-treat analysis, but

with somewhat higher estimated eradication probabilities

(table 3). Secondary analyses examining potential inter

actions showed no significant interactions between

treatment and sex, age, presence of chronic dyspeptic

symptoms at baseline, or study centre (table 4).

Differences between study sites occurred in the overall

probability of eradication in both the intention-to-treat

populations (table 4) and the adherent-to-therapy popu

lation (webappendix), but nowhere was either four-drug

regimen clearly better than standard triple therapy.

Discussion

Our principal outcome measure, the probability of

H pylori eradication, was higher for 14-day standard triple

therapy than for both four-drug regimens, and these

results did not vary significantly by age, sex, study site, or

history of chronic dyspeptic symptoms. The prevalence

of H pylori infection in screened participants was high,

and nearly all individuals who had a positive urea breath

test were randomly assigned into the trial. Participants

tended to adhere closely to the protocol by returning for

their follow-up urea breath test and taking their prescribed

tablets. In the three treatment groups, the difference in

adherence and serious side-effects was small.

H pylori presents a major global health challenge,

which can probably best be addressed through practical,

inexpensive, and population-based interventions in the

resource-limited countries where it is most prevalent.

From this perspective the size of our trial, technical

simplicity, broad geographic coverage within Latin

America, community-based population, use of locally

sourced generic drugs, and statistically robust findings

Helicobacter pylori

eradication

Difference from standard p value for

group (adjusted 95% CI) interaction*

(Continued from previous page)

Study site

Santiago (Chile)

14-day standard

209

69

59 (855%)

028

5-day concomitant

70

46 (657%)

10-day sequential

70

59 (843%)

Tquerres (Colombia)

212

14-day standard

71

58 (817%)

5-day concomitant

72

58 (806%)

11% (135 to 158)

10-day sequential

69

54 (783%)

34% (132 to 200)

Guanacaste (Costa Rica)

14-day standard

210

70

61 (871%)

198% (39 to 357)

12% (136 to 161)

5-day concomitant

70

54 (771%)

100% (44 to 244)

10-day sequential

70

63 (900%)

29% (163 to 106)

Copn (Honduras)

213

14-day standard

70

66 (943%)

5-day concomitant

72

62 (861%)

10-day sequential

71

58 (817%)

Tapachula (Mxico)

210

14-day standard

71

55 (775%)

5-day concomitant

69

50 (725%)

10-day sequential

70

47 (671%)

Ciudad Obregn (Mxico)

210

82% (29 to 192)

126% (08 to 26)

50% (114 to 214)

104% (79 to 285)

14-day standard

70

5-day concomitant

69

47 (681%)

90% (78 to 259)

10-day sequential

71

47 (662%)

109% (74 to 292)

Len (Nicaragua)

14-day standard

199

67

54 (771%)

48 (716%)

5-day concomitant

67

43 (642%)

74% (106 to 255)

10-day sequential

65

44 (677%)

39% (155 to 234)

Subgroup analyses for age, sex, and study site were prespecified; subgroup analyses for chronic dyspeptic symptoms

were not. *p value for drop-in-deviance test for significance of interaction with treatment regimen in a logistic

regression model controlling for main effects of treatment and baseline covariate.

Table 4: Summary of Helicobacter pylori eradication by treatment group and selected baseline

characteristics for intention-to-treat population

across important subgroups reflect the realities of a

region where diseases associated with H pylori are

especially burdensome. Our results are important

because they challenge those of meta-analyses showing

that four-drug regimens (triple therapy plus a

nitroimidazole) given concomitantly or sequentially

were clearly better than triple therapy,1416 and they

suggest that findings based primarily on data from

Europe and other high-income regions might not be

readily generalisable to lower-income countries (panel).

We reported probabilities of H pylori eradication of less

than 80% with 5-day concomitant and 10-day sequential

regimens by the intention-to-treat analysis, whereas

meta-analyses had reported probabilities greater than

90% for both.1416 Investigators of a trial from Taiwan

comparing 10-day regimens of concomitant versus

sequential four-drug therapies also reported that both

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8

See Online for webappendix

Articles

regimens were more than 90% successful.20 The

estimated effectiveness of our three-drug regimen (82%)

in the intention-to-treat analysis was only modestly

greater than that reported in the meta-analyses

(7779%).1416 Thus, the divergence between our findings

and those of the meta-analyses represents the substantially

worse performance of the four-drug regimens.

Geographical variations in the pattern of H pylori

resistance to antibiotics might account for some of the

discrepancies between the results. In clinical series from

several countries included in our trial, clarithromycin

resistance in H pylori isolates has been reported to be less

prevalent than in Europe, and metronidazole resistance

substantially more prevalent (as high as 80%).2124

Clarithromycin resistance strongly diminishes the

effectiveness of triple therapy, so a better outcome with

triple therapy would be expected if the prevalence of

resistance in our trial population was actually low.13,21,25 A

high prevalence of resistance to metronidazole in our

study population is a plausible, but less certain,

explanation for the worse-than-expected success of the

four-drug regimens.25 Results according to antibiotic

resistance are available from only two trials of sequential

therapy versus triple therapy; the combined data showed

that 68 of 71 (96%) patients with metronidazole-resistant

Panel: Research in context

Systematic review

Consensus groups that represent both global and Latin

American perspectives have designated triple-drug regimens

of a proton-pump inhibitor plus amoxicillin and clarithromycin

taken for 714 days as a standard approach for eradicating

Helicobacter pylori.10,11 However, the effectiveness of these

regimens seems to have diminished to unacceptably low levels

over time,12,13 and recent meta-analyses of clinical trials from

Europe and Asia show that four-drug regimens that add

metronidazole or tinidazole to triple therapy achieve superior

results.1416 The reported meta-analyses have not included any

trials that were undertaken in Latin America, an area where

H pylori-associated diseases are common and where wide-scale

eradication programmes might be needed. We did a Medline

search of all publications up to 2010, with no language

restrictions, using the search terms Helicobacter in

combination with the term for each country in Latin America.

No publications of clinical trials that compared 14-day triple,

5-day concomitant, and 10-day sequential therapies for

Helicobacter pylori infection were identified.

Interpretation

Our findings showed that in the Latin American populations

we studied, by contrast with those for European and some

Asian populations, 14-day standard triple therapy is more

effective than 5-day concomitant or 10-day sequential

four-drug regimens that include metronidazole for eradication

of H pylori. Thus, effectiveness of H pylori eradication regimens

in one area might not be as equally effective elsewhere.

organisms were treated successfully with sequential

therapy compared with 46 of 59 (78%) treated with triple

therapy.16,26 No comparable data from trials of concomitant

versus triple therapy are available. The presence of

organisms resistant to both antibiotics would likely cause

treatment to fail for all three studied regimens, but data

for this topic from Latin America are scarce.

We used a 14-day regimen of triple therapy in our trial,

whereas previous trials of the four-drug regimens

generally compared them to 7 days or 10 days of triple

therapy. In one meta-analysis 14-day triple therapy

regimens were slightly, but significantly, superior to

those of 7 days or 10 days; thus, longer duration

conceivably enhanced the performance of triple therapy

in our trial.27 Success with the four-drug regimens

perhaps would also improve with longer duration;13,20,28

however, this would increase their cost.

We recruited our participants from the general adult

population in the community, whereas previous trials

studied patients with gastrointestinal symptoms.1416 The

success of H pylori treatment with triple therapy or

sequential therapy has not been shown to be affected by a

diagnosis of peptic-ulcer disease or dyspepsia, and the

superiority of triple therapy over the four-drug regimens

in our trial did not vary significantly according to history

of chronic dyspeptic symptoms.14

Our trial was undertaken in the general population in

community settings where it was not feasible to mask

the study or to obtain bacterial specimens for antibiotic

sensitivity testing. We also obtained generic drugs from a

variety of sources and did not have a completely objective

way of determining adherence to therapy. Each of these

factors is a potential limitation of the trial, but we doubt

that any of them represents a serious threat to the validity

of our results. Despite the absence of masking, our

principal outcome measure (urea breath test) was

objectively measured and seems unlikely to be biased.

The absence of antibiotic sensitivity data also should not

affect study validity, but it does make it more difficult to

generalise our results to other regions where sensitivity

patterns could be different. Inaccuracies in patient

reports of adherence to therapy could have lowered our

estimates of treatment effectiveness in the subgroup of

participants classified as adherent, but these inaccuracies

would not compromise the validity of the main results

from our intention-to-treat analyses comparing the

relative effectiveness of the three regimens. Lastly,

although we cannot guarantee that the locally available

generic drugs were of uniform efficacy, differences in

treatment response between centres cannot be easily

attributed to variable drug quality, since some of the

greatest differences were seen between Nicaragua and

Honduras, where investigators obtained drugs from the

same source.

For individuals with H pylori infection in much of Latin

America, 14 days of triple therapy is probably the preferred

empiric treatment. Nevertheless, the 87% eradication

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8

Articles

success in participants who adhered to the regimen is

suboptimum in the clinical setting, and its effectiveness

might decrease over time as clarithromycin resistance

increases. Improved H pylori treatment regimens for

Latin American populations could conceivably be

designed on the basis of local antibiotic resistance data.

However, the small number of published reports of

antibiotic resistance in this region generally pertain to

H pylori isolates obtained from symptomatic patients

undergoing endoscopy in urban academic centres, and

thus the results might not be applicable to broader

populations.21 In view of the paucity of representative

data for resistance, and the daunting technical and

financial challenges of obtaining these data, treatment

guidelines for Latin America and other regions with

limited resources might have to rely primarily on the

results of large, simple clinical trials of empiric therapies

in the specific populations to which the guidelines would

apply. These data could be supplemented by subsequent

monitoring of effectiveness in practice over time and by

the results of antibiotic-resistance testing in selected

patients, when feasible.

We designed our study as a preliminary step towards

implementation of programmes of gastric cancer

prevention in Latin America. H pylori-associated gastric

cancer results from a long progression from normal

mucosa to invasive cancer.3,29 The most promising

preventive approach seems to be eradication of H pylori

infection before cancer develops, and several randomised

trials have assessed this strategy. The results show that

eradication of this infection slows or reverses progression

of premalignant histological lesions, but no trial has been

large enough to show a definitive cancer-preventive

effect.30,31 Nevertheless, analyses have suggested that

H pylori eradication programmes would be cost effective

over the long term if they prevented only 10% of gastriccancer deaths; over the short term they would reduce

costs of care for peptic ulcers and dyspepsia symptoms.3234

Eradication programmes are potentially even more cost

effective in regions such as Latin America, where the

burden of H pylori-associated diseases is high.

Our results suggest that population-wide clinical trials

or public health programmes of H pylori eradication are

feasible in Latin America. Individuals with a positive

urea breath test readily agreed to be randomly assigned

to antibiotic treatment, and all three regimens of generic

drugs resulted in probabilities of eradication comparable

to those reported in previous prevention programmes.31

The 14-day triple-drug regimen had superior results, but

the lower cost of the shorter duration regimens might

make them acceptable for use in prevention programmes,

where resources are particularly scarce. Other consider

ations, including risks of recrudescence and reinfection

after eradication, will also be important.

Contributors

All the authors participated in the design and oversight of the trial and

in the interpretation and reporting of results, and have seen and

approved the final report. LEB, RLD, CF, RH, MMM-M, RP, and ES-M

directed the clinical activities at the study centres. GLA had principal

responsibility for the statistical analyses of the data.

Conflicts of interest

DRM has submitted a patent application through the University of

North Carolina for a technique using molecular endoscopy to detect

cancer in the gastrointestinal tract, and has received funding from Axcan

for his participation in a speakers bureau; he has also received a

research grant from AstraZeneca, for a proton-pump inhibitor study in

Hispanic populations in the USA, and from Given Imaging, for ongoing

efficacy studies of colon endocapsule efficacy. All other authors declare

that they have no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided financial support for the

trial, and the National Institutes of Health (Grant number CA037429)

supported the SWOG administrative and statistical infrastructure. We

thank the trial participants for making this study possible and recognise

the many contributions of the investigative team members: SWOG

Statistical Center, Seattle, WA, USAVanessa Bolejack, Susie Carlin,

Dacia Christin, Evonne Lackey, and Rachael Sexton; Division of

Gastroenterology, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, CA, USA

Paris Heidt; Universidad del Valle, Cali, ColombiaLuz Stella Garca,

Yolanda Mora; Hospital Regional de Occidente, Santa Rosa de Copn,

HondurasJean Paul Higuero, Glenda Jeanette Euceda Wood,

Lesby Maritza Castellanos; Pontificia Universidad Catlica de Chile,

Santiago, ChileMara Paz Cook, Paul Harris, Antonio Rolln; Fundacin

INCIENSA, San Jos, Costa RicaSilvia Jimnez, Paula Gonzlez,

Ana Cecilia Rodrguez, Lidiana Morera, Blanca Cruz Reyes; Instituto

Nacional de Salud Pblica, Cuernavaca, MexicoRogelio Danis,

Erika Marlen Hurtado Salgado, Maria del Pilar Hernndez Nevres;

Instituto Tecnolgico de Sonora, Ciudad Obregn, MexicoMyriam Bringas,

Araceli Molina, Claudia Osorio, Mara de Jess Lpez Valenzuela;

Centro de Investigacin en Demografa y Salud, Len, Nicaragua

Yesenia Zapata; and also Charles A Coltman, David S Alberts, and

Jesse Nodora for their help during the course of the study.

References

1 Infection with Helicobacter pylori. IARC working group on the

evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. IARC monographs

on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Vol 61.

Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. Lyon, France:

International Agency for Research on Cancer, 1994: 177240.

2 Lochhead P, El-Omar EM. Gastric cancer. Br Med Bull 2008;

85: 87100.

3 Parkin, DM. The global health burden of infection-associated

cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer 2006; 118: 303044.

4 Ferlay J, Shin HR, Bray F, Forman D, Mathers C, Parkin DM.

Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN

2008. Int J Cancer 2010; 127: 2893917.

5 Marugame T, Dongmei Q. Comparison of time trends in stomach

cancer incidence (19731997) in East Asia, Europe and USA, from

cancer incidence in five continents Vol IVVIII. Jpn J Clin Oncol

2007; 37: 24243.

6 Mathers CD, Loncar D. Projections of global mortality and burden

of disease from 2002 to 2030. PLoS Med 2006; 3: e442.

7 WHO. World Health Report 2003, statistical annex, table 3: sex and

mortality stratum in WHO regions, estimates. http://www.who.int/

whr/2003/en/Annex3-en.pdf (accessed June 28, 2011).

8 Graham DY, Shiotani A. The time to eradicate gastric cancer is now.

Gut 2005; 54: 73538.

9 Malfertheiner P, Mgraud F, OMorain C, et al. Current concepts

in the management of Helicobacter pylori infectionThe

Maastricht III Consensus Report. Gut 2007; 56: 77278.

10 Coelho LG, Len-Bara R, Quigley EM. Latin-American Consensus

Conference on Helicobacter pylori infection. Latin-American

National Gastroenterological Societies affiliated with the

Inter-American Association of Gastroenterology (AIGE).

Am J Gastroenterol 2000; 95: 268891.

11 Chey WD, Wong BCY, Practice parameters committee of the

American College of Gastroenterology. American College

of Gastroenterology practice guidelines on the management of the

Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102: 180825.

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8

Articles

12 Malfertheiner P, Selgrad M. Helicobacter pylori infection and current

clinical areas of contention. Curr Opin Gastroenterol 2010; 26: 61823.

13 Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era

of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut 2010; 59: 114353.

14 Jafri NS, Hornung CA, Howden CW. Meta-analysis: sequential

therapy appears superior to standard therapy for Helicobacter pylori

infection in patients naive to treatment. Ann Intern Med 2008;

148: 92331.

15 Gatta L, Vakil N, Leandro G, Di Mario F, Vaira D. Sequential

therapy or triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori infection: systematic

review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in adults

and children. Am J Gastroenterol 2009; 104: 306979.

16 Essa AS, Kramer JR, Graham DY, Treiber G. Meta-analysis:

four-drug, three-antibiotic, non-bismuth-containing concomitant

therapy versus triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication.

Helicobacter 2009; 14: 10918.

17 Bertuccio P, Chatenoud L, Levi F, et al. Recent patterns in gastric

cancer: a global overview. Int J Cancer 2009; 125: 66673.

18 Morgan DR, Squella FE, Pena E, et al. Multinational validation of

the Spanish Rome III questionnaire: comparable sensitivity and

specificity to the English instrument. Gastroenterology 2010;

138: S-386.

19 Tack J, Talley NJ, Camilleri M, et al. Functional gastroduodenal

disorders. Gastroenterology 2006; 130: 146679.

20 Wu DC, Hsu PI, Wu JY, et al. Sequential and concomitant therapy

with four drugs is equally effective for eradication of H pylori

infection. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 8: 3641.

21 Mgraud F. H pylori antibiotic resistance: prevalence, importance,

and advances in testing. Gut 2004; 53: 137484.

22 Torres J, Camorlinga-Ponce M, Prez-Prez G, et al. Increasing

multidrug resistance in Helicobacter pylori strains isolated from

children and adults in Mexico. J Clin Microbiol 2001; 39: 267780.

23 Alvarez A, Moncayo JI, Santacruz JJ, Santacoloma M, Corredor LF,

Reinosa E. Antimicrobial susceptibility and mutations involved in

clarithromycin resistance in Helicobacter pylori isolates from

patients in the western central region of Colombia.

Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 402224.

24 Vallejos C, Garrido L, Cceres D, et al. Prevalencia de la resistencia

a metrodinazol, claritromicina y tetraciclina en Helicobacter pylori

aislado de pacientes de la Regin Metropolitana. Rev Med Chil 2007;

135: 28793.

25 Fischbach L, Evans EL. Meta-analysis: the effect of antibiotic

resistance status on the efficacy of triple and quadruple first-line

therapies for Helicobacter pylori. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2007;

26: 34357.

26 Zullo A, De Francesco V, Hassan C, Morini S, Vaira D. The

sequential therapy regimen for Helicobacter pylori eradication:

a pooled-data analysis. Gut 2007; 56: 135357.

27 Fuccio L, Minardi ME, Zagari RM, Grilli D, Magrini N, Bazzoli F.

Meta-analysis: duration of first-line proton-pump inhibitor based

triple therapy for Helicobacter pylori eradication. Ann Intern Med

2007; 147: 55362.

28 Graham DY, Shiotani A. New concepts of resistance

in the treatment of Helicobacter pylori infections.

Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 5: 32131.

29 Correa P, Houghton J. Carcinogenesis of Helicobacter pylori.

Gastroenterology 2007; 133: 65972.

30 Parsonnet J, Forman D. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric

cancerfor want of more outcomes. JAMA 2004; 291: 24445.

31 Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, et al. Meta-analysis: can

Helicobacter pylori eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric

cancer? Ann Intern Med 2009; 151: 12128.

32 Parsonnet J, Harris RA, Hack HM, Owens DK. Modelling

cost-effectiveness of Helicobacter pylori screening to prevent gastric

cancer: a mandate for clinical trials. Lancet 1996; 348: 15054.

33 Mason J, Axon AT, Forman D, Leeds HELP Study Group.

The cost-effectiveness of population Helicobacter pylori screening

and treatment: a Markov model using economic data from

a randomized controlled trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2002;

16: 55968.

34 Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, Axon AT, Moayyedi P.

A community screening program for Helicobacter pylori saves

money: 10-year follow-up of a randomized controlled trial.

Gastroenterology 2005; 129: 191017.

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8

Comment

Mass eradication of Helicobacter pylori: feasible and advisable?

In The Lancet, E Robert Greenberg and colleagues1 present

an Article about the efficacy of three different therapeutic

regimens for the eradication of Helicobacter pylori in

several Latin American countries. A large sample of

adults with symptomatic and asymptomatic disease was

studied. Besides aiming to identify the best therapeutic

regimen, the study also served as a preliminary step to

support future programmes of gastric cancer prevention

in the Latin American population. Gastric cancer is the

fifth most common cause of cancer in this region (figure)

and is the leading cause of cancer mortality among males

in many Latin American countries. The study showed

that the 14-day standard therapy with lansoprazole,

amoxicillin, and clarithromycin was superior to both

the 5-day concomitant and sequential four-drug

regimens (lansoprazole, amoxicillin, clarithromycin,

and metronidazole).

Generic (off-patent) preparations of the study drugs

were used in this trial. The use of low-cost generic drugs

is an important factor for public health strategies in

Latin America. These preparations were validated in the

USA2 and the results from the study done by Greenberg

and colleagues show that good quality generic drugs

were used. However, if these drugs are used in large

populations for H pylori eradication, quality control of

these drugs will be crucial. Recent reports have brought

attention to problems related to the quality of generic

drugs, including antibiotics.3,4

Importantly, Greenberg and colleagues study confirms

that the standard therapy, which includes generic drugs,

remains effective in Latin America, by contrast with

developed countries where resistance to clarithromycin

has been identified.5 We believe however, that costs

could be reduced and the potential for development

of resistant bacterial strains could be decreased, if the

standard therapy could be prescribed over a short period

of time. Findings from two studies done 10 years apart

in Brazil using standard therapy over a 10-day period

showed H pylori eradication rates of about 90%.6,7

H pylori affects around 50% of men, with prevalence

much higher in developing countries than in developed

countries (ie, prevalence in North America is 30%,

in Central America 7090%, and in South America

7090%).8 In 1994, the International Agency for Research

on Cancer defined H pylori as a human carcinogen for

gastric adenocarcinoma, raising concerns about how to

treat people with asymptomatic infection.9

A disturbing issue presented by Greenberg and

colleagues is the suggestion of developing a mass

eradication programme for H pylori in Latin America,

aimed at long-term prevention of at least 10% of gastric

cancer cases, and short-term gain of saving money by

reducing care costs associated with peptic ulcer and

dyspepsia symptoms.

Although the role of H pylori in gastric carcinogenesis

is well defined, no definitive evidence shows that mass

eradication could reduce incidence of gastric cancer.10

Wong and colleagues11 showed no benefit in the

prevention of gastric cancer with the eradication of

H pylori. By contrast, a recent meta-analysis suggested that

eradication could indeed reduce the risk of gastric cancer.12

Policies aimed at population-wide H pylori eradication

could have individual and social repercussions.

Amoxicillin could cause fatal anaphylactic reactions,

while clarithromycin has been associated with

increased mortality in patients with ischaemic heart

disease.13 Furthermore, almost all antibiotics can

cause Clostridium difficile infection, which could

eventually become life threatening. Even if infrequent,

these complications could become important when

eradicating H pylori at a population level. Another

Published Online

July 20, 2011

DOI:10.1016/S01406736(11)61099-4

See Online/Articles

DOI:10.1016/S01406736(11)60825-8

Age-standardised mortality

rates per 100 000

Age-standardised mortality

rates per 100 000

0 29 52 85 138 37

0 17 33 49

73

23

Figure: Mortality of gastric cancer in men and women in Latin America (2008)

(A) Number of deaths in men per 100000 people=128. (B) Number of deaths in women per 100000 people=69.

Modified from GLOBOCAN 2008, International Agency for Research on Cancer.

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61099-4

Comment

key point to address is the probability of reinfection.

Annual recurrence of H pylori infection is about 12% in

developing countries.14 However, the most serious issue

relates to development of bacterial resistance for not

only H pylori but potentially many other bacteria.

Thus, we believe that although any public policy aimed

at decreasing the prevalence of H pylori infection could

lead to reductions in gastric cancer and peptic ulcer, the

risks associated with antibiotic use might represent an

important limitation to such a strategy. Furthermore,

restricted financial resources in Latin America represent

a major public health challenge. Therefore, appropriate

studies are needed that compare the effect of investment

in sanitation, hygiene, and education with the effect of

mass eradication of H pylori, to assess which options will

be most beneficial to the Latin American population.

Another possible approach is the development of

effective immunisation as a safer method of decreasing

rate of H pylori infection.15 On the one hand, we are aware

that sanitation and immunisation will not reduce the

risk of H pylori-associated disease for people who are

already infected. On the other hand, doubts exist about

the reversibility of already established precursor lesions

in the carcinogenesis cascade in infected patients. Wong

and colleagues11 showed that eradication significantly

decreased the development of gastric cancer only in the

subgroup of H pylori carriers without precancerous lesions.

Mass eradication is a major issue requiring further

investigation. We agree with Greenberg and colleagues

that future properly designed studies addressing

this issue are essential to assess the balance between

positive and negative effects of each strategy. Local

epidemiological data, among other factors, will dictate

allocation of public health resources: countries with

high mortality rates secondary to gastric cancer, such as

Colombia, Chile, and Guatemala, should discuss whether

development of a programme for mass eradication of

H pylori is worthwhile.

In conclusion, mass eradication of H pylori is potentially

feasible but in view of the differing socioeconomic

realities of Latin American countries, doubts remain

about the advisability of such a policy.

*Luiz Edmundo Mazzoleni, Carlos Fernando Francesconi,

Guilherme Becker Sander

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, School of Medicine,

Porto Alegre, Brazil (LEM, CFF); Hospital de Clnicas de Porto

Alegre, Department of Gastroenterology, Ramiro Barcelos 2350,

Porto Alegre, Brazil 90035903 (LEM, CFF, GBS); and Post

Graduation Program: Gastroenterology and Hepatology,

Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

(LEM, CFF)

lemazzoleni@yahoo.com.br

We declare that we have no conflicts of interest.

1

2

3

4

5

6

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Greenberg ER, Anderson GL, Morgan DR, et al. 14-day triple, 5-day

concomitant, and 10-day sequential therapies for Helicobacter pylori

infection in seven Latin American sites: a randomised trial. Lancet 2011;

published online July 20. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60825-8.

Davit BM, Nwakama PE, Buehler GJ, et al. Comparing generic and innovator

drugs: a review of 12 years of bioequivalence data from the United States

Food and Drug Administration. Ann Pharmacother 2009; 43: 158397.

Zuluaga AF, Agudelo M, Cardeo JJ, et al. Determination of therapeutic

equivalence of generic products of gentamicin in the neutropenic mouse

thigh infection model. PLoS One 2010; 5: e10744.

Nightingale CH. A survey of the quality of generic clarithromycin products

from 18 countries. Clin Drug Investig 2005; 25: 13552.

Graham DY, Fischbach L. Helicobacter pylori treatment in the era

of increasing antibiotic resistance. Gut 2010; 59: 114353.

Mazzoleni LE, Sander GB, Ott EA, et al. Clinical outcomes of eradication

of Helicobacter pylori in nonulcer dyspepsia in a population with a high

prevalence of infection: results of a 12-month randomized, double blind,

placebo-controlled study. Dig Dis Sci 2006; 51: 8998.

Mazzoleni LE, Sander GB, Francesconi CF. Dyspeptic symptoms after

eradication of Helicobacter pylori in patients with functional dyspepsia.

Heroes-12 Trial (Helicobacter Eradication Relief Of Dyspeptic Symptoms).

Gastroenterology 2010; 138 (suppl 1): S-719.

Everhart JE. Recent developments in the epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori.

Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2000; 29: 55978.

International Agency for Research on Cancer Working Group on the

evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Schistosomes, liver flukes, and

Helicobacter pylori: views and expert opinions of an IARC working group on

the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans. Lyon, France: IARC Press,

1994: 177240.

Parsonnet J, Forman D. Helicobacter pylori infection and gastric cancer

for want of more outcomes. JAMA 2004; 291: 24445.

Wong BC, Lam SK, Wong WM, et al. Helicobacter pylori eradication to

prevent gastric cancer in a high-risk region of China: a randomized

controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 291: 18794.

Fuccio L, Zagari RM, Eusebi LH, et al. Meta-analysis: can Helicobacter pylori

eradication treatment reduce the risk for gastric cancer? Ann Intern Med

2009; 151: 12128.

Winkel P, Hilden J, Fischer Hansen J, et al. Excess sudden cardiac deaths after

short-term clarithromycin administration in the CLARICOR trial: why is this

so, and why are statins protective? Cardiology 2011; 118: 6367.

Niv Y. H pylori recurrence after successful eradication. World J Gastroenterol

2008; 14: 147778.

Del Giudice G, Malfertheiner P, Rappuoli R. Development of vaccines

against Helicobacter pylori. Expert Rev Vaccines 2009; 8: 103749.

www.thelancet.com Published online July 20, 2011 DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61099-4

You might also like

- Health Policy in Portugal July 2016Document2 pagesHealth Policy in Portugal July 2016carlosvalxNo ratings yet

- Health Policy in Slovak Republic March 2017Document2 pagesHealth Policy in Slovak Republic March 2017carlosvalxNo ratings yet

- Health Policy in United Kingdom July 2016Document2 pagesHealth Policy in United Kingdom July 2016carlosvalxNo ratings yet

- Health Policy in Germany July 2016Document2 pagesHealth Policy in Germany July 2016carlosvalxNo ratings yet

- (Vladimir LolitaDocument216 pages(Vladimir Lolitacarlosvalx75% (4)

- 1407 AustraliaDocument46 pages1407 AustraliacarlosvalxNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Pranic Healing PrincipleDocument6 pagesPranic Healing Principleapi-26172340100% (2)

- Main Idea and Text Structure 3Document1 pageMain Idea and Text Structure 3Anjo Gianan TugayNo ratings yet

- .0. Cognitive Behavioral ManagementDocument2 pages.0. Cognitive Behavioral ManagementMarcela PrettoNo ratings yet

- Mental Health of GNM PDFDocument133 pagesMental Health of GNM PDFSuraj Solanki0% (1)

- Basic Principle of Electrotherapy1Document61 pagesBasic Principle of Electrotherapy1drng480% (1)

- What Is Aquatic TherapyDocument5 pagesWhat Is Aquatic TherapyHaslindaNo ratings yet

- NCP For Chronic PainDocument11 pagesNCP For Chronic PainRYAN SAPLADNo ratings yet

- Malignant 2021 480p WEB-DL x264 400MB-Pahe inDocument59 pagesMalignant 2021 480p WEB-DL x264 400MB-Pahe inBranislav IvanovicNo ratings yet

- Templates AnaDocument16 pagesTemplates AnaWilfredo DecasaNo ratings yet

- Endocrinology: Diabetes: Courses in Therapeutics and Disease State ManagementDocument59 pagesEndocrinology: Diabetes: Courses in Therapeutics and Disease State Managementnuttiya_w3294No ratings yet

- SyncopeDocument105 pagesSyncopeJohn DasNo ratings yet

- A Topical Approach To Life-Span Development Chapter 1Document51 pagesA Topical Approach To Life-Span Development Chapter 1randy100% (5)

- Sigmund Freud Essay - WordDocument9 pagesSigmund Freud Essay - Wordapi-2493113410% (1)

- HERNIIDocument4 pagesHERNIISeceleanu MarianNo ratings yet

- RobynneChutkan MicrobiomeSolutionDocument20 pagesRobynneChutkan MicrobiomeSolutionAdarsh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Drugs: What Is A Drug??Document9 pagesDrugs: What Is A Drug??Alyzza BorrasNo ratings yet

- Hall Adolescent Assessment ReportDocument3 pagesHall Adolescent Assessment Reportapi-404536886No ratings yet

- Isolation 1Document16 pagesIsolation 1Surabhi RairamNo ratings yet

- 21 Nursing ProblemDocument32 pages21 Nursing Problemjessell bonifacioNo ratings yet

- Drug Study - CaDocument3 pagesDrug Study - Casaint_ronald8No ratings yet

- New Problem StatementDocument2 pagesNew Problem Statementrenuka rathore100% (2)

- Drug Study FormatDocument2 pagesDrug Study FormatEmilie CajaNo ratings yet

- Risedronate SodiumDocument3 pagesRisedronate Sodiumapi-3797941No ratings yet

- Manajemen NyeriDocument8 pagesManajemen Nyeriagung yulisaputraNo ratings yet

- The Mental Health Review GameDocument134 pagesThe Mental Health Review Gamemeanne073No ratings yet

- Proofed - Nurs 3021 Final EvaulDocument20 pagesProofed - Nurs 3021 Final Evaulapi-313199824No ratings yet

- Neurosurgical Emergencies: Craig Goldberg, MD Chief, Division of Neurosurgery Bassett HealthcareDocument44 pagesNeurosurgical Emergencies: Craig Goldberg, MD Chief, Division of Neurosurgery Bassett HealthcareTolaniNo ratings yet

- @medicalbookpdf Preeclampsia PDFDocument286 pages@medicalbookpdf Preeclampsia PDFgalihsupanji111_2230No ratings yet

- Initial Management of Blood Glucose in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - UpToDateDocument24 pagesInitial Management of Blood Glucose in Adults With Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus - UpToDateJessica ArciniegasNo ratings yet

- TTSH Nursing Survival GuideDocument96 pagesTTSH Nursing Survival GuideSarip Dol100% (2)