Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Expressive Collective Action Phillip Jones

Uploaded by

Tias BradburyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Expressive Collective Action Phillip Jones

Uploaded by

Tias BradburyCopyright:

Available Formats

doi: 10.1111/j.1467-856x.2006.00262.

BJPIR: 2007 VOL 9, 564581

The Logic of Expressive Collective

Action: When will Individuals

Nail their Colours to the Mast?

Philip Jones

Individuals do not act collectively simply because they recognise common interests; collective interests

can be defined as collective goods and collective goods are non-excludable. In large groups

instrumental individuals have no incentive to act because individual action is imperceptible. But

are individuals always this instrumental? If it is a mistake to assume that collective action occurs

naturally when common interests are recognised, it is a mistake to ignore awareness of common

interests. Individuals derive satisfaction from expressing identity with common interests but when

will individuals choose to nail their colours to the mast?

Keywords: expressive; instrumental; collective action

Mancur Olson (1965) rejected the supposition that awareness of common interests

is sufficient to explain collective action. He predicted that a member of a large

group would not voluntarily support an association even if the association had the

potential to advance a groups common interests (e.g. by lobbying for legislative

change). Each member of the group would recognise that a common goal is freely

available; benefits derived from collective action are not contingent on providing

support. Contribution to an association is tantamount to revealing demand for a

collective good. A collective good is non-rival in consumption and non-excludable;

consumption by one individual does not reduce availability to others. If it is

irrational to reveal demand for a non-excludable good, why incur costs to support

an association? The dominant strategy is to free-ride but if all behave rationally

nothing is achieved (there is no free ride).

Olsons analysis does not rely on the assumption that individuals are self-interested.

Even if the member of a large group were to neglect his own interests entirely, he

still would not rationally contribute toward the provision of any collective or public

good since his own contribution would not be perceptible (Olson 1965, 64). The

critical assumption is that behaviour is instrumental (to change outcome). Why act

if action would not be perceptible? Olsons distinction between small and large

groups is premised on this consideration. In large groups individual action is

imperceptible; in small groups individual action can exert an impact on outcome

(Buchanan 1968). Members of a small group might act collectively but large groups

remain latent (Olson 1965).

While Olson distinguished between market groups and non-market groups (e.g.

between firms acting as cartels and groups pressing for legislative change to advan 2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

565

tage the community as a whole), the focus was on instrumental motivation. Patrick

Dunleavy (1991, 77) suggests that associations can be structured to increase perceptions that individual action might be significant. Size manipulation is possible

if influence exerted in a small subset of the association would imply influence in the

association as a whole. Again the emphasis is on action to change outcome. But

surely motivation depends on more than ability to influence outcome? The architects of utility theory identified many sources of utility but the evolution of the

utility concept during our century has been characterised by a progressive stripping

away of psychology (Lowenstein 1999, 315). Bentham (1948 [1789]) argued that

utility is derived from action, quite apart from outcome contingent on action. Is it

really sufficient to assume that the only motivation to act is to change outcome?

There is already more than a hint of another dimension. Collective action is far

more prevalent than predicted (Johansen 1977; Ledyard 1995); empirical studies

insist that perceptions of the intrinsic value of action are relevant (e.g. Andreoni

1988 and 2001; Frey 1997). An individual is intrinsically motivated to perform an

activity when one receives no apparent reward except the activity itself (Deci 1971,

105). Olson focused on action as an investment (to change outcome). What if

individuals also derive consumption from action (Lee 1988)?

Intrinsic value is derived in different ways. Individuals may feel better about

themselves if they act with dignity. Self-esteem might depend on the signal emitted

(to oneself and to others). In behavioural experiments, individuals derive a warm

glow from philanthropic action (Andreoni 1988 and 2001). Action can also yield

intrinsic interest; the difference between liking and disliking work may well be

more important than remuneration (Scitovsky 1976, 103). While all sources of

intrinsic value are relevant the focus in this article falls on action to express identity.

The term identity is used to describe a persons social category (Akerlof and

Kranton 2005, 12, emphasis original). Individuals choose action that creates identity; John Wallis (2003, 227) notes that people define who they are in terms of the

people they interact with and how they interact. Even when identity is preordained (e.g. by race, nationality, etc.) individuals still choose whether to emphasise

identity. George Akerlof and Rachel Kranton (2005, 12) argue that [i]n a model of

utility ... a persons identity describes gains and losses in utility from behaviour that

conforms or departs from the norms for particular social categories in particular

situations.

To explain collective action as a predilection to act collectively explains everything

merely by re-describing it (Barry 1970, 33). Olsons lesson is well taken; his

critique of existing explanations (e.g. by Bentley 1908; Truman 1951) reveals that

individuals do not act collectively just because they [have] similar feelings and

ideals (Dougherty 2003, 29). There is a distinction between common interests and

individual interests. Individuals might be aware of common interests but have no

incentive to act to express identity with common interests. Individuals might derive

utility from action that signals identity with common interests but remain unwilling

to incur the costs. But, does this imply that awareness of common interests should

simply be ignored? If it is a mistake to explain action as recognition of common

interests, it is a mistake to ignore awareness of common interests. Individuals derive

intrinsic value from expressing identity with common interests. The challenge is to

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

566

PHILIP JONES

predict when the perceived intrinsic value of this action exceeds the costs that must

be incurred. Recent empirical studies offer insight; behaviour can be explained with

reference to systematic changes in the perceived intrinsic value of action (e.g. Frey

1997; Gneezy and Rustichini 2000).

The following section revisits the by-product theory of action by large groups.

Analysis premised only on instrumental motivation leaves many questions unanswered, so much so that, in later sections of the article, the question is not whether

to embrace analysis of willingness to express identity but how to embrace analysis

of willingness to express identity.

1. The Logic of Expressive Collective Action

Olson (1965) analysed collective action as a by-product. In the absence of coercion

(closed shop arrangements) associations mobilise large groups by offering selective incentives (e.g. cheap insurance, a journal, an invitation to a social or gala

occasion, etc.all contingent on membership). When individuals are instrumental,

the larger the group the farther it will fall short of providing an optimal supply of

a collective good and very large groups normally will not, in the absence of coercion

or separate outside incentives, provide themselves with even minimal amounts of

a collective good (Olson 1965, 48).

The by-product theory is now common currency.1 The following examples illustrate the inducement of a private good. An instrumental individual is asked to

contribute 5 to finance pursuit of a collective goal. Achievement of the common

objective is worth the equivalent of 10 to the individual. In Table 1 net payoff is 5

if the individual contributes and others contribute. If others do not contribute, a

single contribution will not matter; there is a loss of 5. If the individual makes no

contribution and others contribute, the individual gains the equivalent of 10 (by

free-riding on provision by others); if others also refuse to contribute the payoff is

zero. Payoffs from not contributing dominate those from contributing.

The association might induce action by offering each contributor a private good

worth the equivalent of 6. The cost of contribution is now 5.5 (the additional

0.5 is required to cover the cost of the private good). Payoffs in Table 2 reveal that

the individuals dominant strategy is now to contribute.

It appears a simple matter to demonstrate that a private-good inducement will alter

the balance of payoffs and create an incentive to act. However, this refinement begs

Table 1: Collective Action: The Free-Rider Problem

Contribution

No contribution

Others contribute

Others do not

contribute

10 - 5 = 5

10

-5

0

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

567

Table 2: Collective Action and Selective Incentives

Contribution

No contribution

Others contribute

Others do not

contribute

10 - 5.5 + 6 = 10.5

10

-5.5 + 6 = 0.5

0

so many questions. If the selective incentive is to prove successful, private benefits

must be cheap enough to produce for the surplus generated from contributions to

be large enough to provide both the collective consumption good and the private

benefits (Laver 1997, 40). The inducement must generate sufficient financial

surplus (in this case a minimum of 5 per member for the collective consumption

good). But:

(1) If a financial surplus must be generated there is a profit. If there is a profit

there is an incentive to private firms to produce this private good (Stigler

1974). Surely, private goods (selective incentives) will be supplied by private

firms in the market?

(2) If private firms have an incentive to produce the private good, private firms

are at a competitive advantage. Private firms are able to offer private goods and

services at a lower price (because private firms are not committed to incur

costs to provide a collective good). How are associations to survive?

(3) Even if the association survives, where is the motivation to invest any part of

the financial surplus to provide a common goal? If members are not motivated

by pursuit of the collective goal, political entrepreneurs have no incentive to

devote funds to provide the collective good (this will have no effect on

subscription to associations). Why do associations supply collective goods

(Stigler 1974; Fireman and Gamson 1979; Udehn 1996)? Even if some

members did join the union as a result of the selective benefits on offer,

yielding a surplus for the union that could be deployed in the production of

collective benefits, why would union officials deploy their surplus in this

way? (Laver 1997, 41).

Laver emphasises that political entrepreneurs must be secular saints for the

theory to hold (they must forgo pecuniary gain to devote profit to a common

cause). Of course philanthropy is possible (Glaeser and Schleifer 1998) but the

by-product theory is far from robust (if it appears to rely on a contrived

asymmetry between entrepreneurial aspirations in market and non-market

structures).

(4) Although so many key theoretical questions remain unanswered, critics

usually focus on empirical investigation. If private-good inducements really

provide the motivation, why do empirical studies insist that private goods and

services (selective incentives) are of little concern to members? Questionnaire

studies report that members have little interest in selective incentives. Respondents insist that their motivation is pursuit of common interests (Jordan and

Maloney (1996 and 1998) review this literature).

Some argue that respondents may have misunderstood questions or answered

dishonestly. But such concern is endemic to questionnaire analysis. With

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

568

PHILIP JONES

Table 3: Collective Action: Signalling Identity

Contribution

No contribution

Others contribute

Others do not contribute

10 - 5.5 + 5.8 + 0.2 = 10.5

10

-5.5 + 5.8 + 0.2 = 0.5

0

consensus across questionnaire studies (and the absence of competition from

private firms), perhaps individuals are answering honestly?

Surely something is missing? The analytical importance of selective incentives is

that they explain how a group might be mobilised. They do not explain why a

group exists (the presumption is that individuals are already aware of group

interests). Consider the difference if analysis also embraces individuals choice to

express identity with group interests. In this case selective incentives play a more

complex role. Acquisition of selective incentives also signals identity with common

interests. Selective incentives are invariably distinguishable by design. They take

the form of flags, badges, bumper stickers, sweatshirts with associated logos and

attendance at symbolic events. Selective incentives offer an intrinsic, expressive

gain (SE) as well as a gain derived from the enjoyment of a private good in its own

right (SP).

In Table 3 the expressive gain from acquisition of a selective incentive (as a signal)

is 5.8; the value of a private good (in its own right) is only 0.2. In each cell of

Table 3 there are the same net payoffs as in Table 2. Once again the individual will

contribute but now the analysis is quite different.

Even though net payoffs are identical in Tables 2 and 3, the configuration of gains

in Table 3 matters:

(1) It is no longer necessary that the value of the private goodin its own

rightexceeds the cost of producing the private good. In Table 3 the cost of

the private good is 0.5 and the value of the good, in its own right, is 0.2. If

the value of the private good (as a private good) is less than the cost of

production, there is no incentive for private firms to supply these goods.

(2) The expressive value of signalling identity with common interests depends on

perceptions of the esteem in which common interests are held. Private goods

supplied by private firms yield SP but not SE. Purchase of a symbolic selective

incentive from a private firm lacks credibility as a symbol of identity. Receipt

of a symbolic selective incentive from an association yields SP + SE because the

association also commits resources in pursuit of a common goal. Associations

now have an advantage.

(3) As selective incentives signal identity with common interests there is a rationale to devote resources to a common cause. The expressive gain from acquisition of symbolic selective incentives (SE) depends on pursuit of a collective

goal.

(4) If private goods also signal identity with common interests, questionnaire

responses resonate with theoretical predictions. Even if the value of the

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

569

private good, in and of itself, is negligible (as in Table 3), selective incentives

induce action (to express identity). There is no inconsistency if respondents

insist their main concern is the common goal.

There is evidence that selective incentives play a dual role. Charles Cell (1980)

analysed associations in the USA and reported that private-good inducements (as

private goodsdelivering SP) increased when associations concern with ideological

objectives decreased (and the capacity to deliver SE diminished). One more direct

test is possible. If Olsons analysis (premised only on instrumental rationality) is

apposite, selective incentives furnish revenue to pursue the collective goal (a

one-way relationship). If willingness to pay to express identity is also relevant,

selective incentives finance pursuit of a collective goal but now they are more

attractive (as signals of identity) the more the association spends on pursuit of

common interests (a two-way relationship). Statistical analysis of associations

finances reveals a two-way relationship: Revenues generated on selective incentives ... are contingent on the level of spending on public goods (Lowry 1997,

308).2

2. Willingness to Express Identity

A plethora of criticisms of the by-product theory suggest that behaviour depends

on more than instrumental rationality. A consistent response to criticisms expressed

independently emerges when analysis embraces willingness to express identity.

There is scope for analysis of willingness to express identity, but can predictions be

formed?3

(a) Determinants of the Intrinsic Value of Identity

For Akerlof and Kranton (2005, 12) the term identity is used to describe a persons

social category. It captures how people feel about themselves as well as how those

feelings depend upon their actions. In the military sector and the civilian sector,

output is higher when individuals bond with common goals; effort is not simply a

function of remuneration. The question is what determines perceptions of the

intrinsic value of expressive action. Analysts report that intrinsic value depends on

moral considerations and also on extrinsic signals (e.g. Deci and Ryan 1980 and

1985; Frey 1997); signals that acknowledge action enhance perceptions of intrinsic

value.

A first signal is political rhetoric. Like Hamlet without the Prince, the script fails to

do justice to the role played by political leadership when it is premised only on

instrumental rationality (McLean 2001). If, in Table 1, political rhetoric were to

magnify perceptions of the value of achieving a common goal (say from 10 to

100or to 10,000), the decision is still to attempt to free-ride. If rhetoric minimises perceptions of the value of costs (from 5 to say 0.05), free-riding remains

the dominant strategy. The contrast is stark when comparing the impact of rhetoric

on perceptions of the intrinsic value of action. Returning to Table 3, rhetoric has

only to raise perceptions of the intrinsic value of signalling identity from 5.2 to

5.8 for the decision to change from apathy to participation. Political rhetoric extols

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

570

PHILIP JONES

the virtues of doing the right thing. Producers of mass participation (Schuessler

2000, 91) are often successful when relying on a symbol-intensive, expressiveattachment-inviting approach (ibid., 87). Empiricists estimate the impact that

leaders ethical posture exerts on followers (Vitell and Davis 1990).

A second signal capable of informing perceptions of intrinsic value is the status of

the association. Henry Hansmann (1980) argues that charitable status helps to

reassure instrumental donors that donations are unlikely to be misappropriated

(because administrators have no legal entitlement to any financial surplus). But this

status also acknowledges the importance of action.

Turning to empirical studies of private giving, consider the importance of signals

emitted by government. If only instrumental rationality were relevant, private

giving to charities would decrease on a one-for-one basis when government assists

beneficiaries of private charities (Warr 1982). Altruism is a public good (e.g. Collard

1978) and altruists would free-ride. But, in practice crowd-out parameters are far

less than one (usually 0.1 and very rarely as high as 0.6Schiff 1989 and Jones and

Posnett 1993 survey empirical work). There is also evidence of crowd-in (for a

survey see Jones 2005). Crowd-in is possible because the actions of others seem to

serve as cues to guide behaviour rather than ... as strategies to be counteracted

(Roy 1998, 417). Jones et al. (1998) report this demonstration effect when analysing private giving in the UK. Signals that acknowledge the status of action inform

perceptions of the value of action.

A third determinant of perceptions of intrinsic value is the nature of common

interests. If common interests are collective goods, collective goods have two characteristics. Collective goods are non-excludable and non-rival in consumption.

Non-rivalness in consumption means that consumption by one individual does not

reduce availability to others (McLean 1987). Goods can be classified with reference

to the rate at which availability atrophies when access broadens (e.g. Head 1962;

Buchanan 1968; Musgrave 1969; Craig 1987).4 There is a considerable difference

(for example) between collective action that provides a swimming pool (rival in

consumption above capacity limits) and collective action that provides medical

research (to produce information capable of reducing everyones probability of

contracting a disease).5

Olson focused almost exclusively on the first characteristic, non-excludability

(Olstrom 2003). Implicitly, many of his examples considered the incentive to

contribute to goals that are more rival in consumption.6 Instrumental willingness to

take action is greater the more rival the good. Action matters because it is important

to secure a share of the (rival) output that will be produced. The greater the

incentive to secure a share of output the greater the instrumental incentive to act.

In Figure 1 willingness to pay is reported on the vertical axis and degree of nonrivalness (between 0 and 1) on the horizontal axis. Instrumental motivation (I)

decreases as the degree of non-rivalness increases.

By contrast, the more that common interest is non-rival in consumption, the

greater the intrinsic value of action from expressing identity because it is more

obvious that such action is not simply self-serving. Share of output is no longer

pertinent if one individuals consumption does not reduce availability to others

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

571

Figure 1: Instrumental and Expressive Motivation

I+E

Instrumental

motivation

Expressive

motivation

Degree of non-rivalness

(Jones 2004). Expressive motivation (E) increases with the degree to which

common interests are non-rival in consumption. Robert Putnam (1993, 89) refers

to the relevance of the degree to which common goals are encompassing. Hudson

and Jones (2005) present empirical evidence that individuals are more willing to act

collectively (as altruists) when consumption by others does not reduce availability

of a collective good. E is not a mirror image of I in Figure 1; the position and slope

of E also depend on political rhetoric, charitable status, etc.

Predictions resonate in empirical studies:

(1) Motivation to act collectively depends on the degree to which common interests are non-rival in consumption. David Knoke (1990) analysed 35 associations in the National Association Survey in the USA. Of 35 associations, 15

were classified as political. Classification was based on responses by leaders of

associations. Leaders of the 15 more frequently asserted that lobbying was an

important task (a far greater percentage of the 15 reported that they made

frequent representation to federal government). The motivation of members

was assessed with reference to members questionnaire responses. For the 15,

political activity was cited as the main reason to join by 35 per cent of

members (compared to only 6 per cent of the 4,347 sample members of the 20

non-political organisations). By contrast, 53 per cent of the membership of

non-political organisations gave job-related concerns as the motive for membership (compared to 35 per cent of the membership of 15 political organisations). Members motivations for joining were not distributed randomly

across types of collective action organisations. An associations purpose may

shape its members motivations for involvement (Knoke 1990, 125).

(2) As suggested by the dashed U-shaped function (I + E) in Figure 1, there is a

very clear distinction between groups motivated primarily by instrumental

concerns and groups motivated primarily by willingness to express identity.

Kenneth Shepsle and Mark Bonchek (1997) review empirical studies. They

highlight the distinction between economic associations (trade associations,

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

572

PHILIP JONES

trade unions) focused on more rival goals (higher profits, higher wages) and

expressive associations in pursuit of goals that are less rival. Members of

economic groups join primarily for the selective benefits ... while members of

non-economic groups join primarily for the collective benefits (Shepsle and

Bonchek 1997, 249).

The nature of common interests matters when analysing willingness to act to

express identity. It also matters when considering the way that organisations are

classified. Private firms supply excludable and rival goods (they operate in an

environment in which individuals acquire property rights). Clubs supply excludable

and (below capacity levels) non-rival services (Buchanan 1965). Common pool provision supplies non-excludable but rival services (Olstrom 2003); cartels provide

non-excludable but rival goals when they strive to maximise profit that is rival

between member firms. Representative associations pursue non-excludable and nonrival goals.

(b) The Price of Expressive Action

Perceptions of intrinsic value change systematically but individuals are only willing

to act if perceived intrinsic value exceeds the price that must be paid. Constraints

play a more prominent role than when analysis is premised only on instrumental

motivation. If analysis is premised only on instrumental motivation (as in Table 1),

free-riding remains the individuals optimal strategy whether income is high or

low. But, in practice income matters; income is a strong predictor of giving to

political campaigns (e.g. Ansolabehere et al. 2003) and donations to charities (e.g.

Schiff 1989). What about price?

One way to test the relevance of price is to compare behaviour in different fora. In

the following examples all of the variables remain the same, i.e. the instrumental

gain from achieving a common goal (B), the probability that action might affect

outcome (p), costs of action (C) and the consumption gain from expressive action

(E) are the same. Net expected utility of action is:

pB + E C > 0

(1)

and expressive action is worthwhile if:

E > C pB

(2)

It follows that the price of expressive action is C-pB (price is equal to the cost of

contribution net of any prospective instrumental gain). The price of expressive

action may vary in different fora because price depends on the way costs and

benefits are framed (Tversky and Kahneman 1981; McDermott 2001).

In the first forum an altruist is asked to donate 5 to finance a home for the elderly.

The altruist feels the equivalent of 10 better off if the home is provided and derives

intrinsic value equivalent to 4 by expressing identity with this cause. Table 4

illustrates payoffs. While the individual is aware of common interests there is no

willingness to express identity by contributing (payoffs from not contributing

dominate).

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

573

Table 4: Collective Action: Identity by Donation

Contribution

No contribution

Others

contribute

Others do not

contribute

10 - 5 + 4 = 9

10

-5 + 4 = -1

0

Table 5: Collective Action: At the Ballot Box

Vote for

Vote against

Others vote for

Others vote

against

10 - 5 + 4 = 9

10 - 5 = 5

0 + 4 = +4

0

In the second example the same individual decides whether to vote for publicsector provision of the home for the elderly. The tax cost is 5 per person. The

gain from identity at the ballot box (self-signalling) by voting for is equivalent to

4. In this forum the price of expressive action is systematically lower. The individual is aware that their vote has virtually no impact on electoral outcome and

the tax-cost is only relevant if a majority votes in favour. The individual can vote

for (and identify with the goal) knowing that this will have a negligible impact

on the electoral outcome (and on incurring a tax-cost). The price of expressive

action is lower even though p, B, C and E are identical (in this forum price

is equal to p(C-B) because the cost to the individual of expressing identity with

common interests is only relevant if there is a probability, p, that a single vote will

lead to a tax-cost). In Table 5 payoffs from action to express identity are now

dominant.

Evidence again proves consistent with predictions premised on analysis of expressive collective action; individuals vote charitably and act selfishly (Tullock 1973,

27). For reviews of empirical studies, see Brennan and Lomasky (1993); Hudson

and Jones (1994); Udehn (1996); and Mueller (2003). Even if expressive gain were

greater by donating than voting, the principle remains robust. Price of expressive

action varies in different fora and willingness to act collectively is greater when

price is lower.

3. Willingness to Express Identity: Implications when

Analysing Political Participation

Recent empirical studies shed insight on the determinants of perceptions of willingness to express identity and on the importance of the price of expressive action.

Empirical studies highlight the significance of expressive action (e.g. Akerlof and

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

574

PHILIP JONES

Kranton 2005); individuals behave as if they derive a consumption gain from

action to signal self-image (to themselves and to others). Individuals derive utility

from outcomes contingent on action and from action to express identity. The

individual may be conceived as having a perfectly standard utility function which

includes reference to both the value of various consequential outcomes, and the

value of various expressions or acts (Brennan and Hamlin 2002, 302). While the

instrumental account ... is sometimes taken to be a defining feature of the rational

actor approach to politics (Brennan and Hamlin 1998, 149), the authors emphasise

the importance of expressive action in large number situations. Collective action

can be predicted with reference to systematic response to determinants of perceptions of the intrinsic value of expressive action and with reference to changes in the

price of expressive action.7

In this section the focus falls on the implications when analysing interest group

activity and when analysing other forms of political participation. The first insight

is with respect to alternative assessments of interest group competition. The second

is with respect to apparently anomalous alignments of interest groups. In both cases

analysis that encompasses expressive action provides value added. In the third

example the value added is in terms of new issues that would otherwise be ignored;

the approach raises questions that would not be asked if behaviour were motivated

only by action to change outcome.

(1) Different assessments of interest group activity. Some analysts (Olson 1965 and

1982; Tullock 1965) emphasise the waste (e.g. lower economic growth) that

occurs when instrumental groups compete for rents (e.g. for legislation that

will deliver remuneration above payment received in competitive environments). Others applaud collective action, arguing that it can instil ... habits of

co-operation, solidarity and public spiritness and a sense of shared responsibility (Putnam 1993, 8990; Knack 2003). Different assessments can be

explained with reference to Figure 1. More instrumental groups (e.g. economic associations) frequently waste resources (competing for transfers from

one section of the community to anothergoals that are rival in consumption). Expressive groups are more likely to inculcate a sense of shared responsibility, by focusing on goals that are non-rival in consumption (and have the

potential to benefit one and all).

(2) Anomalous alignments of interest groups. With reference to wastes incurred competing for transfers, Gordon Tullock (1997 and 1998) asks repeatedly why

they are so much lower than anticipated (e.g. the empirical analysis of Ansolabehere et al. 2003 reports lower than anticipated costs). At the same time,

another set of studies expresses surprise that apparently disparate groups align

to press for legislative change. Bruce Yandle (1989, 34) is surprised that

regulation of the Sunday sale of booze ties together bootleggers, Baptists and

the legal operators of liquor stores. Achim Krber (1998) notes the curious

alignment between environmentalists and producers of canned tuna lobbying

for legislation in the USA to protect dolphins (in the 1980s US producers were

supplied with tuna from dolphin friendly waters).

If wastes are lower and harmony greater than anticipated it is because politicians more easily accommodate pressures when individuals, motivated prima 2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

575

rily by the immediacy of a consumption gain derived from expressive action,

have little incentive to monitor outcomes (Jones 2006). When civil and

religious groups press for international aid (Kaul and Conceio 2006), governments offer tied aid that proves inefficient because it also delivers

higher profits to domestic producers (Jones 2006). When there is pressure for

trade sanctions against oppressive regimes, governments design sanctions to

serve the interests of import-competing domestic producers (Kaempfer and

Lowenbourg 1988), even though the design means that trade sanctions

seldom achieve their goals (van Bergeijk 1994) in terms of the goals set by

expressive groups.

(3) New issues when individuals act to express identity. If the contest between different

groups is less fierce than anticipated (because those motivated by an expressive gain have little incentive to monitor outcome) there are new concerns.

Analysis of group activity premised only on instrumental motivation indicates

that small groups might exploit large groups if small groups are able to

free-ride on the contribution made by large groups (Olson 1965; Olson and

Zeckhauser 1966). But, when contributions to groups are also motivated by

expressive identity there are new concerns, that those who contribute to

express identity (contributors who have no incentive to monitor outcomes)

might be exploited by those who contribute more instrumentally. Exploitation occurs if expressive groups can be manipulated.8

While these examples focus on interest group activity, there are implications when

analysing political participation more generally. If individuals only motivation

were instrumental (to change outcome) there would be no incentive to turn out to

vote because the probability that an individual vote will change an electoral

outcome is minuscule. But, in practice, turnout rates are high even in national

elections (Aldrich 1993); Grofman (1993) refers to the paradox that ate public

choice.

Electoral turnout might be explained with reference to the importance of action

that expresses identity with the community, i.e. with reference to action that fulfils

civic duty. Jones and Hudson (2000) report evidence that turnout in the 1997 UK

general election fell because the election had been preceded by a plethora of

allegations of political sleaze, allegations that demeaned the intrinsic value of

expressions of civic duty. Some argue that more than one motivation is also

relevant when explaining other forms of participation. Paul Whiteley and Patrick

Seyd (1996) analyse the motives of party activists. They examine the motivation of

activists in the UK Labour Party and conclude that activists are more expressively

attached to the party than inactive members, despite the fact that the incentives to

free ride are the same for strongly attached individuals as they are for weakly

attached individuals (ibid., 227). Justin Fisher and Paul Webb (2003) analyse the

motivation of those employed by political parties. While employees are instrumentally responsive to the terms of their contract, motivation is not purely instrumental. After interview analysis, the authors report the following comment by an

employee of the Labour Party: the first reason, nine times out of ten, is the feeling

that you work for something that you believe in (ibid., 179).

If expressive motivation is important when explaining why individuals participate,

expressive motivation is also relevant when explaining how individuals participate.

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

576

PHILIP JONES

Jones and Dawson (forthcoming) consider the relevance of instrumental evaluation

of policies presented by political parties and the intrinsic value of expressing identity

with a preferred political party. The intrinsic value of expressing party identity

proved significant when explaining choice at the 2002 UK general election. Geoffrey Brennan and Alan Hamlin (1998) argue that this motivation is relevant when

explaining why political parties divert from anticipated policy manifestos and adopt

preferred symbolic policy options. Alexander Schuessler (2000) emphasises this

motivation when explaining how politicians set out to win support; they rely on

inclusive statements rather than instrumental discussion of policy options.

The issue of how individuals express choice is also important when analysing

preference for constitutional rules. If analysis is premised only on instrumental

motivation, the value of ... institutions is to be assessed in terms of the outcomes

producedin a manner analogous to that in which market institutions are judged

by reference to the allocation of resources that they induce (Brennan and Hamlin

2002, 310). But, if expressive motivation is important, democratic institutions are

assessed in terms of what those institutions stand for. If these democratic values

might be among expressive concerns of individuals, then in many settings ... these

expressive preferences for particular aspects of democratic institutions per se will be

systematically over-emphasised to the detriment of more instrumental concerns

(Brennan and Hamlin 2002, 310).

The impact of expressive action on well-being is the remit for another paper. There

are instances in which willingness to express identity mobilises collective action to

produce outcomes that would be under-supplied. In Table 3 it is the private consumption gain from expressive action [5.8 - 5.5] that explains willingness to act

collectively and it is the same private consumption gain that explains why the

common goal is achieved. In Table 3 the individual is ultimately better off by

[10 + 5.8 - 5.5 + 0.2] because, if the individual is representative, all act collectively and the common goal is achieved. However, there are also instances in which

willingness to express identity can reduce well-being.9 In this article the proposition

is simply that willingness to express identity cannot be dismissed when explaining

collective action. Signals that inform perceptions of the intrinsic value of action can

prove more potent than instrumental evaluation of outcome (Jones 2003).

Conclusions

As Olson (1965) argued, provision of a private good by an association will change

payoffs and induce instrumental individuals to act collectively. But, as an explanation of collective action this analytical refinement brings in its wake many questions. If the private good were the individuals only concern, the individual would

purchase the good from a private firm. If an association managed to survive

competition from private firms there would be no rationale to devote a financial

surplus to a collective goal. Questionnaire analysis insists that the private good is a

minor concern. When analysis embraces willingness to express identity individuals

also derive satisfaction from expressing self-image. Selective incentives now play a

dual role. They serve as private goods and they also serve to signal identity. If their

relevance as a symbol is greater when they signal identity with an association that

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

577

pursues a common goal, private firms are unable to compete. There is a rationale to

devote a financial surplus to a common goal. Questionnaire responses prove consistent with theoretical predictions.

Collective action can be analysed with reference to the determinants of perceptions

of the intrinsic value of expressing identity with an association. Empirical studies

report systematic behavioural responses. Perceptions of the intrinsic value of action

depend on: ethical posture by political leaders; the status afforded to associations;

and the degree to which common interests are non-rival in consumption. The

degree to which common goals are non-rival in consumption can prove as important as the extent to which common goals are non-excludable.

It has not been argued that collective action is simply a reflection of awareness of

common interests. A distinction must be drawn between the intrinsic value of

expressing identity and the price that must be paid. Individuals might recognise

common interests but have no inclination to express identity with common interests. Willingness to act depends on both perceptions of the intrinsic value of action

and on the price that must be paid. Willingness to act collectively increases if the

perceived intrinsic value of expressive action increases and if the price of expressive

action falls.

Analysis of a private consumption gain derived by expression of identity explains

existing anomalies when analysing interest group competition and raises new

questions (questions that would not be asked if analysis were narrowly premised on

instrumental motivation). It offers insight on the different alignments that exist

between different groups but, in so doing, it also calls in question the possibility that

action by expressive groups might be exploited by those who act more instrumentally. The question of why and how individuals choose to signal self-image (to

themselves and to others) is important when analysing political participation. The

smaller the likelihood that individual action will affect outcome, the greater the

relevance of analysis of willingness to pay to express identity.

Olsons lesson has been well taken, but perhaps too well taken? Awareness of

common interests will not lead naturally to collective action but awareness of

common interests should not be ignored. Too many pieces of the jigsaw are missing

when analysis studiously ignores individuals willingness to nail their colours to

the mast.

About the Author

Philip Jones, Professor of Economics, Department of Economics and International Development,

University of Bath, Bath, BA2 7AY, UK, email: P.R.Jones@bath.ac.uk

Notes

1. It is applied generally. For example, political revolution has been analysed as a career-enhancing

opportunity to secure a better position in a post-revolution government (Tullock 1971; Silver 1974;

Jennings 1998).

2. Hansen (1985) argues that expenditure on a collective good advertises an associations selective

incentives. This explanation implies that private goods are more attractive the more is spent on

pursuit of a common goal.

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

578

PHILIP JONES

Table 6: Collective Action and Frames of Reference

Acquire a symbol

Not acquire a symbol

Others acquire a symbol

Others do not acquire a

symbol

-5 + 5 - 4 = -4

-5

+5 - 4 = 1

0

3. It is not necessary here to consider why utility is derived from identity; this is the remit for another

paper. Some suggest that signalling identity with a common goal enhances reputation for trustworthiness. Frank (1988) analyses the role played by conscience. He suggests that this generates an aura

that others can detect and that expression of identity is relevant for the instrumental pursuit of long

run objectives. All of this is freely acknowledged. Here the focus is narrower; the proposition is that

analysis of collective action is incomplete if willingness to pay to express identity is ignored.

4. If output of an association is defined as X and the number in the group is N, the extent to which a

goal is non-rival is gauged by the exponent h when the amount available for any individual (i) is

qi = X/Nh. When h = 0 the good is non-rival in consumption; when h = 1 the good is rival in

consumption.

5. McLean (1987, 11) notes that Non-rival means that it is not subject to crowding. If G is non-rival

the relationship of the total provision to consumption by individuals A, B and C is G = GA = GB = GC;

if X were rival the relationship is X = XA + XB + XC.

6. Chamberlin (1974) illustrates how the theoretical force of Olsons examples is heightened by choosing collective goods more rival in consumption; Esteban and Ray (2001) offer further analysis of the

relevance of this characteristic.

7. In this journal Dowding (2005 and 2006) and Parsons (2006) have explored the implications that

arise if individuals are motivated to take action because they perceive that they have a duty to act.

Analysis in this article assumes that individuals act because they derive utility from action and, as

Brennan and Hamlin note, in making choices of all sorts, the individuals will behave in a manner that

is consistent with the standard axioms of rationality given such a utility function. Individuals

willingness to give greater emphasis to expressive action depends on (i) perceptions of the intrinsic

value of such action; (ii) institutional structures [that] change the terms of trade between instrumental and expressive elements (Brennan and Hamlin 2002, 302). Both instrumental and expressive

action might prove commensurate but if (in large group situations) there is no motivation to act to

change outcome, the individual might still be motivated to act to express identity.

8. Ethical investing (in the UK and USA) can be explained in terms of willingness to identify with a cause

deemed worthy but there are increasing calls for codes of conduct to restrain instrumental fund

management and ensure that outcomes better match aspirations expressed (see e.g. Cullis et al.

2006).

9. Table 6 reports payoffs when an individual acts to acquire a good simply to signal status. The cost is

4. If others are unable to acquire the good, the payoff is (5 - 4). If others purchase the good, the

status gain of 5 is cancelled. If the individual does not acquire the good, the individual is 5 worse

off when others purchase the good. But if no one purchases the good there is no effect on welfare.

Each individual is motivated to acquire the good to express identity, but if all behave this way, each

person is worse off (by -5 + 5 - 4 in Table 6). There is collective action, albeit informal, but

expression of identity by conspicuous consumption can reduce well-being.

Bibliography

Akerlof, G. and Kranton, R. E. (2005) Identity and the economics of organizations, Journal of Economic

Perspectives, 19:1, 932.

Aldrich, J. (1993) Rational choice and turnout, American Journal of Political Science, 37:1, 246278.

Andreoni, J. (1988) Privately provided goods in a large economy: The limits of altruism, Journal of Public

Economics, 35:1, 5773.

Andreoni, J. (2001) The economics of philanthropy, in N. J. Smelser and P. B. Bates (eds), International

Encyclopaedia of the Social and Behavioural Sciences (London: Elsevier), 1136911376.

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

579

Ansolabehere, S., de Figueiredo, J. M. and Snyder J. Jr (2003) Why is there so little money in US

Politics?, Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17:1, 105130.

Barry, B. (1970) Sociologists, Economists and Democracy (London: Collier-Macmillan).

Bentham, J. (1948 [1789]) The Principles of Morals and Legislation (New York: Macmillan).

Bentley, A. (1908) The Process of Government (Evanston IL: Principia Press).

Brennan, G. and Hamlin, A. (1998) Expressive voting and electoral equilibrium, Public Choice, 95:12,

149175.

Brennan, G. and Hamlin, A. (2002) Expressive constitutionalism, Constitutional Political Economy, 13:4,

299311.

Brennan, G. and Lomasky, L. (1993) Democracy and Decision: The Pure Theory of Electoral Preference (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Buchanan, J. M. (1965) An economic theory of clubs, Economica, 32:125, 114.

Buchanan, J. M. (1968) The Demand and Supply of Public Goods (Chicago IL: Rand McNally).

Cell, C. P. (1980) Selective incentives versus ideological commitment: The motivation for membership in

Wisconsin farm organizations, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 62:2, 517524.

Chamberlin, J. R. (1974) Provision of collective goods as a function of group size, American Political Science

Review, 68:2, 707716.

Collard, D. (1978) Altruism and Economy (Oxford: Martin Robertson).

Craig, S. C. (1987) The impact of congestion on local public good production, Journal of Public Economics,

33:3, 331353.

Cullis, J., Jones, P. and Lewis, A. (2006) Ethical investing: Where are we now?, in M. Altman (ed.),

Handbook of Economic Psychology (London: M. E. Sharpe), 602605.

Deci, E. L. (1971) Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation, Journal of Personality and

Social Psychology, 18:1, 105115.

Deci, E. L. and Ryan, R. M. (1980) The empirical exploration of intrinsic motivational processes, in L.

Berkowitz (ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 13 (New York: Academic Press).

Deci, E. L. and Ryan, R. M. (1985) Intrinsic Motivation and Self Determination in Human Behavior (New York:

Plenium Press).

Dougherty, K. L. (2003) Precursors of Mancur Olson, in J. Heckelman and D. Coates (eds), Collective

Choice Essays in Honor of Mancur Olson (New York: Springer-Verlag), 1732.

Dowding, K. (2005) Is it rational to vote? Five types of answers and a suggestion, British Journal of Politics

& International Relations, 7:3, 442459.

Dowding, K. (2006) The D-Term: A reply to Stephen Parsons, British Journal of Politics & International

Relations, 8:2, 299302.

Dunleavy, P. (1991) Democracy, Bureaucracy, Public Choice: Economic Explanations in Political Science (London:

Harvester).

Esteban, J. and Ray, D. (2001) Collective action and the group size paradox, American Political Science

Review, 95:3, 663672.

Fireman, B. and Gamson, W. D. (1979) Utilitarian logic in the resource mobilization perspective, in M.

N. Zald and J. D. McCarthy (eds), The Dynamics of Social Movements (Cambridge MA: Winthrop

Publishers), 844.

Fisher, J. and Webb, P. (2003) Political participation: The vocational motivations of Labour party

employees, British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 5:2, 166187.

Frank, R. (1988) Passions within Reason (New York: Norton).

Frey, B. S. (1997) Not Just for the Money: An Economic Theory of Personal Motivation (Cheltenham: Edward

Elgar).

Glaeser, E. L. and Schleifer, A. (1998) Not-for-Profit Entrepreneurs (Working Paper 6810) (Cambridge MA:

National Bureau of Economic Research).

Gneezy, U. and Rustichini, A. (2000) Pay enough or dont pay at all, Quarterly Journal of Economics,

115:13, 791810.

Grofman, B. (1993) Is turnout the paradox that ate rational choice theory?, in B. Grofman (ed.),

Information, Participation and Choice (Ann Arbor MI: University of Michigan Press), 93103.

Hansen, J. M. (1985) The political economy of group membership, American Political Science Review, 79:1,

7996.

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

580

PHILIP JONES

Hansmann, H. B. (1980) The role of nonprofit enterprise, Yale Law Journal, 89, 835898. Reprinted in S.

Rose-Ackerman, The Economics of Nonprofit Institutions (New York: Oxford University Press), 5784.

Head, J. G. (1962) Public goods and public policy, Public Finance/Finances Publiques, 17:3, 197219.

Hudson, J. and Jones, P. (1994) The importance of the ethical voter: An estimate of altruism,

European Journal of Political Economy, 10:3, 499509.

Hudson, J. and Jones, P. (2005) Public goods: An exercise in calibration, Public Choice, 124:34,

267282.

Jennings, C. C. (1998) An economistic interpretation of the Northern Ireland conflict, Scottish Journal of

Political Economy, 45:3, 294308.

Johansen, L. (1977) The theory of public goods: Misplaced emphasis, Journal of Public Economics, 7:1,

147152.

Jones, P. (2003) Public choice in political markets: The absence of quid pro quo, European Journal of

Political Research, 42:1, 7793.

Jones, P. (2004) All for one and one for all: Transactions cost and collective action, Political Studies, 52:3,

450468.

Jones, P. (2005) Consumers of social policy: Policy design, policy response, policy approval. Social Policy

and Society, 4:3, 237249.

Jones, P. (2006) A public choice analysis of international co-operation, in I. Kaul and P. Conceio (eds),

The New Public Finance (New York: Oxford University Press), 304324.

Jones, P. R., Cullis, J. G. and Lewis, A. (1998) Public versus private provision of altruism: Can fiscal policy

make individuals better people?, Kyklos, 51:1, 324.

Jones, P. and Dawson, P. (forthcoming) Choice in collective decision-making processes: Instrumental or

expressive approval?, Journal of Socio-Economics.

Jones, P. and Hudson, J. (2000) Civic duty and expressive voting: Is virtue its own reward?, Kyklos, 53:1,

316.

Jones, A. M. and Posnett, J. W. (1993) The economics of charity, in N. Barr and D. Whynes (eds), Current

Issues In the Economics of Welfare (London: Macmillan), 130152.

Jordan, G. and Maloney, W. A. (1996) How bumble bees fly: Accounting for public interest participation,

Political Studies, 44:4, 668685.

Jordan, G. and Maloney, W. A. (1998) Manipulating membership: Supply-side influences on group size,

British Journal of Political Science, 28:2, 389409.

Kaempfer, W. H. and Lowenburg, A. D. (1988) The theory of international economic sanctions: A public

choice approach, American Economic Review, 78:4, 786793.

Kaul, I. and Conceio, P. (2006) The New Public Finance: Responding to Global Challenges (New York: Oxford

University Press).

Knack, S. (2003) Groups, growth and trust: Cross-country evidence on the Olson and Putnam hypotheses, Public Choice, 117:34, 341355.

Knoke, D. (1990) Organizing for Collective Action: The Political Economies of Associations (New York: Aldine De

Gruyter).

Krber, A. (1998) Why everybody loves Flipper: The political economy of the US dolphin safe laws,

European Journal of Political Economy, 14:3, 475509.

Laver, M. (1997) Private Desires, Political Action (London: Sage).

Ledyard, J. O. (1995) Public goods: A survey of experimental research, in J. H. Kagel and A. E. Roth

(eds), The Handbook of Experimental Economics (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press), 111181.

Lee, D. R. (1988) Politics, ideology and the power of public choice, Virginia Law Review, 74:2, 191199.

Lowenstein, G. (1999) Because it is there: The challenge of mountaineering for utility theory, Kyklos,

52:3, 315344.

Lowry, R. C. (1997) The private production of public goods: Organizational maintenance, managers

objectives and collective goals, American Political Science Review, 91:2, 308323.

McDermott, R. (2001) The psychological ideas of Amos Tversky and their relevance for political science,

Journal of Theoretical Politics, 13:1, 533.

McLean, I. (1987) Public Choice: An Introduction (Oxford: Basil Blackwell).

McLean, I. (2001) Rational Choice and British Politics: An Analysis of Rhetoric and Manipulation from Peel to Blair

(Oxford: Oxford University Press).

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

EXPRESSIVE COLLECTIVE ACTION

581

Mueller, D. (2003) Public Choice III (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Musgrave, R. A. (1969) Provision for social goods, in J. Margolis and M. Guitton (eds), Public Economics

(New York: St Martins Press), 124144.

Olson, M. Jr (1965) The Logic of Collective Action: Public Goods and the Theory of Groups (Cambridge MA:

Harvard University Press).

Olson, M. Jr (1982) The Rise and Decline of Nations (New Haven CT: Yale University Press).

Olson, M. and Zeckhauser, R. (1966) An economic theory of alliances, Review of Economics and Statistics,

48:3, 266279.

Olstrom, E. (2003) How types of goods and property rights jointly affect collective action, Journal of

Theoretical Politics, 15:3, 239270.

Parsons, S. (2006) The rationality of voting: A response to Dowding, British Journal of Politics & International Relations, 8:2, 295298.

Putnam, R. D. (1993) Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy (Princeton NJ: Princeton

University Press).

Roy, L. (1998) Why we give: Testing economic and social psychology accounts of altruism, Polity, 30:3,

383415.

Schiff, J. (1989) Tax policy, charitable giving and the non-profit sector: What do we really know? in R.

Magat (ed.), Philanthropic Giving (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 128142.

Schuessler, A. A. (2000) A Logic of Expressive Choice (Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press).

Scitovsky, T. (1976) The Joyless Economy: An Inquiry into Human Satisfaction and Consumer Satisfaction (Oxford:

Oxford University Press).

Shepsle, K. A. and Bonchek, M. S. (1997) Analyzing Politics: Rationality, Behaviors and Institutions (New York:

Norton).

Silver, M. (1974) Political revolution and repression: An economic approach, Public Choice, 17:1, 6371.

Stigler, G. J. (1974) The free riders and collective action: An approach to the theories of economic

regulation, The Bell Journal of Economics and Management Science, 5:2, 360372.

Truman, D. (1951) The Governmental Process: Political Interests and Public Opinion (New York: Adolph Knopf).

Tullock, G. (1965) The welfare costs of tariffs, monopolies and theft, Western Economic Journal, 5:3,

224232.

Tullock, G. (1971) The paradox of revolution, Public Choice, 11:1, 8999.

Tullock, G. (1973) The Economics of Charity (London: Institute of Economic Affairs).

Tullock, G. (1997) Where is the rectangle?, Public Choice, 91:2, 149159.

Tullock, G. (1998) Which rectangle?, Public choice, 96:34, 405410.

Tversky, A. and Kahneman, D. (1981) The framing of decisions and the psychology of choice, Science,

211:4481, 453458.

Udehn, L. (1996) The Limits of Public Choice (London and New York: Routledge).

Van Bergeijk, P. A. G. (1994) Economic Diplomacy, Trade and Commercial Policy (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar).

Vitell, S. J. and Davis, D. L. (1990) The relationship between ethics and job satisfaction: An empirical

investigation, Journal of Business Ethics, 9:6, 489494.

Wallis, J. J. (2003) The public promotion of private interest (groups), in J. Heckelman and D. Coates

(eds), Collective Choice Essays in Honor of Mancur Olson (New York: Springer-Verlag), 219246.

Warr, P. G. (1982) Pareto optimal redistribution and private charity, Journal of Public Economics, 19:1,

2141.

Whiteley, P. F. and Seyd, P. (1996) Rationality and party activism: Encompassing tests of alternative

models of political participation, European Journal of Political Research, 29:2, 215234.

Yandle, B. (1989) Bootleggers and Baptists in the market for regulation, in J. S. Shogren (ed.), The

Political Economy of Government Regulation (London: Kluwer), 2954.

2007 The Author. Journal compilation 2007 Political Studies Association

BJPIR, 2007, 9(4)

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Marxist Analysis by Christians: Pedro Arrupe, S. JDocument7 pagesMarxist Analysis by Christians: Pedro Arrupe, S. JTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- JM Bonino, Towards A Christian Political EthicsDocument4 pagesJM Bonino, Towards A Christian Political EthicsTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- Camille Paglia FeminismDocument14 pagesCamille Paglia FeminismTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- Gustavo Morello, Catholic Church and The Dirty WarDocument8 pagesGustavo Morello, Catholic Church and The Dirty WarTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- Rolando Concatti, Testimonio CristianoDocument2 pagesRolando Concatti, Testimonio CristianoTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- Peronismo y CristianismoDocument67 pagesPeronismo y CristianismoTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- Pastore, MAría - Utopía Revolucionario de Los '60Document1 pagePastore, MAría - Utopía Revolucionario de Los '60Tias BradburyNo ratings yet

- Paula Canelo, El Proceso en Su LaberintoDocument2 pagesPaula Canelo, El Proceso en Su LaberintoTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- GESE Guide For Teachers - Advanced Stage - Grades 10-12Document36 pagesGESE Guide For Teachers - Advanced Stage - Grades 10-12Tias Bradbury100% (1)

- Marcelo Gabriel Magne, MSTMDocument3 pagesMarcelo Gabriel Magne, MSTMTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- JM Bonino, Revolutionary Theology Comes of AgeDocument3 pagesJM Bonino, Revolutionary Theology Comes of AgeTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- Grossberg Identity Cultural Studies Is That All There Is PDFDocument11 pagesGrossberg Identity Cultural Studies Is That All There Is PDFTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- Unexplained Phenomena and Events - TrinityDocument4 pagesUnexplained Phenomena and Events - TrinityTias Bradbury0% (1)

- Hombre Nuevo - Monseñor Eduardo F. PironioDocument3 pagesHombre Nuevo - Monseñor Eduardo F. PironioTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- SW, Which FeminismsDocument72 pagesSW, Which FeminismsTias BradburyNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Notes Managerial EconomicsDocument34 pagesNotes Managerial EconomicsFaisal ArifNo ratings yet

- IFS - Chapter 2Document17 pagesIFS - Chapter 2riashahNo ratings yet

- Agriculture: Agritourism in The Era of The Coronavirus (COVID-19) : A Rapid Assessment From PolandDocument19 pagesAgriculture: Agritourism in The Era of The Coronavirus (COVID-19) : A Rapid Assessment From Polandapril_jingcoNo ratings yet

- Establishing Room RatesDocument11 pagesEstablishing Room RatesSumit PratapNo ratings yet

- Economic Survey 2017 18Document399 pagesEconomic Survey 2017 18Aman singhNo ratings yet

- Chapter - 5: Risk and Return: Portfolio Theory and Assets Pricing ModelsDocument23 pagesChapter - 5: Risk and Return: Portfolio Theory and Assets Pricing Modelswindsor260No ratings yet

- Impact of Dowry System On Indian SocietyDocument24 pagesImpact of Dowry System On Indian SocietyTanushka shuklaNo ratings yet

- Someone Said Comparing Real and Nominal GDPDocument6 pagesSomeone Said Comparing Real and Nominal GDPbachir awaydaNo ratings yet

- Ce40 Lecture1Document79 pagesCe40 Lecture1Louie AnchetaNo ratings yet

- NPTELOnline CertificationDocument66 pagesNPTELOnline CertificationAkash GuruNo ratings yet

- PpeDocument5 pagesPpeXairah Kriselle de OcampoNo ratings yet

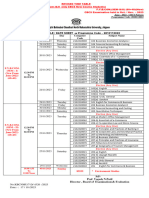

- Revised Time Table of FY-SY-TYBCom Sem I To VI New Old CBCS-CGPA Exam - To Be Held in Oct Nov-2023Document5 pagesRevised Time Table of FY-SY-TYBCom Sem I To VI New Old CBCS-CGPA Exam - To Be Held in Oct Nov-2023Viraj SharmaNo ratings yet

- Answer CH 7 Costs of ProductionDocument11 pagesAnswer CH 7 Costs of ProductionAurik IshNo ratings yet

- Economic Issue - Concentration of Economic PowerDocument8 pagesEconomic Issue - Concentration of Economic PowerAmandeep KaurNo ratings yet

- SMATH311LC InventoryPart1Document8 pagesSMATH311LC InventoryPart1Ping Ping0% (1)

- Soil and Land Management in A Circular Economy PDFDocument6 pagesSoil and Land Management in A Circular Economy PDFAdelina96No ratings yet

- PPT7-Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply As A Model To Describe The EconomyDocument29 pagesPPT7-Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply As A Model To Describe The EconomyRekha Adji PratamaNo ratings yet

- DerivativesDocument125 pagesDerivativesLouella Liparanon100% (1)

- Mtu Global Issues Exam 2 KeyDocument18 pagesMtu Global Issues Exam 2 Keycudahadav8No ratings yet

- Capital MarketDocument5 pagesCapital MarketBalamanichalaBmcNo ratings yet

- CVP Analysis Theory QuizDocument3 pagesCVP Analysis Theory QuizHazel Ann PelareNo ratings yet

- Itc Case Study - September5Document21 pagesItc Case Study - September5Sagar PatelNo ratings yet

- Module 1 DBA Econ HonorsDocument3 pagesModule 1 DBA Econ HonorsREESE ABRAHAMOFFNo ratings yet

- Ryerson Finance 601 Test BankDocument4 pagesRyerson Finance 601 Test BankKaushal BasnetNo ratings yet

- JPM Global Data Watch Money-MultiplierDocument2 pagesJPM Global Data Watch Money-MultiplierthjamesNo ratings yet

- Quiz 3 - Answers PDFDocument2 pagesQuiz 3 - Answers PDFShiying ZhangNo ratings yet

- Hispanics and Latinos in TorontoDocument32 pagesHispanics and Latinos in TorontoHispanicMarketAdvisorsNo ratings yet

- Ch. Charan Singh University Meerut: Regular & Self-Financed CoursesDocument88 pagesCh. Charan Singh University Meerut: Regular & Self-Financed CoursesAmit KumarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3Document5 pagesChapter 3Anh Thu VuNo ratings yet

- Business Plan PresentationDocument17 pagesBusiness Plan Presentationbsmskr0% (1)