Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Computers & Education: Monica Johannesen, Ola Erstad, Laurence Habib

Uploaded by

Claudia Jaramillo MartínezOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Computers & Education: Monica Johannesen, Ola Erstad, Laurence Habib

Uploaded by

Claudia Jaramillo MartínezCopyright:

Available Formats

Computers & Education 59 (2012) 785792

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Computers & Education

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/compedu

Virtual learning environments as sociomaterial agents in the network of teaching

practice

Monica Johannesen a, *, Ola Erstad b, Laurence Habib c

a

Faculty of Education, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences, P.O. Box 4, St Olavsplass, 0130 Oslo, Norway

Institute of Educational Research, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1161, Blindern, 0318 Oslo, Norway

c

Faculty of Technology, Art and Design, Oslo and Akershus University College of Applied Sciences P.O. Box 4, St Olavsplass, 0130 Oslo, Norway

b

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 20 October 2011

Received in revised form

29 February 2012

Accepted 27 March 2012

This article presents ndings related to the sociomaterial agency of educators and their practice in

Norwegian education. Using actor-network theory, we ask how Virtual Learning Environments (VLEs)

negotiate the agency of educators and how they shape their teaching practice. Since the same kinds of

VLE tools have been widely implemented throughout Norwegian education, it is interesting to study how

practices are formed in different parts of the educational system. This research is therefore designed as

a case study of two different teaching contexts representing lecturers from a higher education institution

and teachers from primary schools. Data are collected by means of interviews, online logging of VLE

activities and self-reported personal logs. From the analysis of the data, three main networks of aligned

interests can be identied. In each of those, the sociomaterial agency of the teaching practice with VLE is

crucial in shaping and consolidating the network.

2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Virtual learning environment

Agency

Actor-network theory

Sociomaterial

1. Introduction

To what extent digital technologies have an impact on the social practice of teaching is still an evolving eld of research (Sutherland,

Robertson, & John, 2008). A key issue is how educators dene their teaching practice, what Schn (1983) describes as knowledge-inaction, the knowledge that is embedded in the skilled action of the professional. In many ways, educators may be described as the

archetype of an autonomous professional, exercising professional agency (Turnbull, 2005) based on the heuristics of the professional code of

practice. Such a code seems to be more important than the rules and regulations implemented in their institutions formal systems

(Johannesen & Habib, 2010).

A sociomaterial perspective, as argued for in this article, places a special focus on the interrelationship between technologies as material

tools and their social framings (Latour, 2005). In particular, the literature on sociomateriality highlights the importance of recognizing the

constitutive entanglement of the social and the material in everyday life (Orlikowski, 2007, p. 1435). Westergren (2011), using an example

from Coyne (2010), explicates how technologies can be seen as: outcome of a tuning process (as in tuning a radio), where technology is

positioned within a ow of material agency that is harnessed, directed and domesticated, this interactively stabilizing both material and

human agency toward a human goal (p. 27).

Our focus is on teaching practices, which are normally strongly inscribed with a denite pattern of action, i.e. a specic idea of what needs

it addresses, whose needs those are, and what the end-result of the teaching process is meant to be. At the same time, educators have

preconceptions, norms and values that come into play when they use learning technologies, which have an impact on their interpretations

and translations of those technologies into practice. We narrow down our analysis to the use of virtual learning environments (VLE) within

teaching practices. The existing literature on VLEs in educational settings gives relatively little attention to sociomaterial power relations in

general, and to the agency of educators in particular, i.e. to their ability to act according to their pedagogical beliefs. Analysis of sociomaterial

agency (Suchman, 2007, p. 261) implies an interest in studying the autonomy or boundedness of educators when using VLE as part of their

teaching practices.

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 4722452881, 4790528162 (mobile).

E-mail addresses: monica.johannesen@hioa.no (M. Johannesen), ola.erstad@ped.uio.no (O. Erstad), laurence.habib@hioa.no (L. Habib).

0360-1315/$ see front matter 2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2012.03.023

786

M. Johannesen et al. / Computers & Education 59 (2012) 785792

In this article we aim to investigate the negotiation processes that occur between VLE technologies and the agency of teaching staff

members, with a particular focus on how VLEs may contribute to shaping teaching practices. We rst attempt to provide a denition of the

concept of VLE based on existing research. We then outline our conceptual framework grounded in Actor-Network Theory (ANT). We

subsequently present the methods and data from a study that spans across different educational levels in the Norwegian education system.

Finally, we describe three network constructions that may be delineated within the data presented.

2. Virtual learning environment

Technology development has spawned a signicant interest in what virtual learning environments are and their implications for

teaching and learning. Scholars in the eld of education, in addition to those in e.g. anthropology, media, and computer science have made

contributions to the notion of virtual worlds. However, Weiss (2006) considers that the notion of virtual learning environment is still

unclear and requires further investigation. As learning technologies are becoming more mainstream, he argues, there is a real concern that

the expectations of what they can do to support learning are speculative, as the existence of an application does not necessarily guarantee

success as intended (Weiss, 2006, p. 4). Furthermore, he assumes a broad understanding of the notion of VLEs and makes a distinction

between virtual learning and learning virtually: virtual learning is reserved for computer-based learning environments, while learning

virtually can be done without technology, with analogue artefacts such as paintings, music, theatre, etc. The two terms do merge in contexts

where the digital representation of learning environments uses procedures that existed prior to computer age, such as sending mails and

writing essays.

However, the term virtual learning environments has evolved over the last couple of decades (Mueller & Strohmeier, 2011) and is now

used to refer to software packages that include a number of applications aiming to support course administration (for example student

statistics and information dissemination through news and bulletin boards), communication (for example online discussion fora), online

publishing (for example uploading documents) and assessment (for example student portfolios) (Becta ICT Research, 2004; Britain & Liber,

1999).

Most research in the eld of virtual learning environments concerns the benets of using VLE tools in teaching and learning (see for

example Lazakidou & Retalis, 2010; Limniou & Smith, 2010; Weiss, Nolan, Hunsinger, & Trifonas, 2006). However, less is known about the

processes that take place in the daily practice of teaching staff when using VLEs, with a few notable exceptions. Alvarez, Guasch, and Espasa

(2009) present a theoretical analysis of the roles and competences of teaching staff when online learning environments are used in higher

education. On the basis of an extensive review of the literature, they suggest that teaching staff in universities hold at least ve different

roles, which can be referred to as 1) the designer/planning role, 2) the social role, 3) the cognitive role, 4) a role in operating the technological domain and 5) one in handling the managerial domain. Lonn and Teasley (2009) have investigated how the use of VLE supports

traditional classroom teaching by examining user log data and survey data reported by instructors and students. The data from their

research suggest that the main added value of VLEs as educational tools seems to be their power in making teaching more efcient. One

possible contribution to understanding teaching practice is to investigate them through the lens of sociomaterial agency, i.e. the mutual

shaping of human action and technological constraints and affordances.

3. Conceptual framework

The notion of agency is described by Castor and Cooren (2006) as the capacity to make a difference (p. 573). Human capacity for selfobjectication and self-direction is shaped by both social relations of power and their possibilities for liberation from these forces (Holland,

Lachicotte Jr., Skinner, & Cain, 1998). Hence, in a study of pedagogical practice, it is necessary to understand the processes of negotiation,

conguration and reconguration that are a part of teaching practice, and in particular the capacity for undertaking these negotiations in

relation to the use of technological artefacts.

Nespor (1994) suggests that in order to achieve an understanding of knowledge acquisition processes, it is necessary to study practice in

specic pedagogical settings as well as the networks that are formed together with the artefacts in use. Several theoretical positions,

including situated learning, activity theory and actor-network theory, have been used to explore learning contexts as practically and

discursively performative, emerging from and shaped by actions in networks (Edwards, 2009).

When technology is implemented to support pedagogical processes, it affects and is affected by a number of stakeholders that are linked

with each other either in the form of a network of aligned interests or, in some cases, a number of divergent networks. Actor-network

theory (ANT) has been described as being a theory of knowledge, agency and machines (Law, 1992), originally emerging from the eld

of science and technology studies. Although ANT has been used as an epistemological basis for research studies in a large spectre of

disciplines, including epidemiology (e.g. Young, Borland, & Coghill, 2010), management (e.g. Mulcahy & Perillo, 2011), human geography

(e.g. Hitchings, 2003; Ruming, 2009), environment studies (e.g. Holield, 2009; Murdoch, 2001) and design studies (Yaneva, 2009), it has

not traditionally been a central approach within the eld of education (Fenwick & Edwards, 2010). The few ANT-informed scholarly works

within the realm of education studies (among which gure Nespor (1994) and Fox (2009)) are typically wide-ranging investigations of

teaching and learning processes. The topic of VLE use in higher education has rarely been investigated from an ANT perspective with the

notable exception of Samarawickrema and Stacey (2007).

From an ANT perspective, agency is equally distributed between humans and non-humans (Fox, 2009). Although the concept of power

relations, in particular as the capacity to inscribe, negotiate and translate knowledge in a network is central in the ANT literature, there does

not seem to be a signicant focus on agency in the early literature on ANT. Nevertheless, as early as 1992, Law (1992) presented agency as

network and insisted that social agents are never located in bodies and bodies alone,. but rather as a patterned network of heterogeneous

relations, or an effect produced by such a network (p. 4).

One of the distinctive elements of ANT is that it questions the dominant position of the social in the theorisation of the social systems,

and proposes the principle of generalized symmetry, i.e. that human and non-human actors ought to be treated symmetrically (Callon,

1986a; Callon, Law, & Rip, 1986; Latour, 1993), with similar analytical devices. The use of a single concept, that of actant (Callon, 1986b;

Latour, 1988), to describe both human and non-human actors, epitomizes the principle of generalized symmetry. Actants can be dened

M. Johannesen et al. / Computers & Education 59 (2012) 785792

787

simply as entities that do things (Latour, 1992, p. 241) or entities that bring about action. In that sense, human and non-human actants are

assigned agency of similar importance.

A brief survey on more recent ANT literature (Edwards, 2009; Fenwick, 2010; Fenwick & Edwards, 2010; Latour, 2005) reveals a greater

attention towards the notion of agency. Two distinct conceptions of agency emerge from those works. The rst conception of agency focuses

on the existence of agency among non-humans, and thereby the necessity of treating humans and non-humans with the same analytical

framework. The second conception of agency is centred on a network effect, i.e. an effect of different forces interconnected within

a network (Fenwick, 2010; Fenwick & Edwards, 2010). Framing ANT as a learning theory assumes that learning takes place between people

and materials as part of social practices, which are networked together, acting as one. When a tool or another type of artefact is designed, its

properties play an active role in the negotiation of practice.

We therefore propose to use some concepts from ANT to describe the complex constellation of associations between humans and nonhumans that underlie teaching and learning processes. ANT offers a framework that allows us to look at identity and practice as functions of

on-going interaction with distant elements (animate and inanimate) of networks that have been mobilized along intersecting trajectories

(Nespor, 1994, p. 13). The theory thereby puts a special emphasis on drawing a picture of the processes of creation, development and

sometimes dissolution of hybrid networks, i.e. networks consisting of human and non-human actors.

Our discussion will be based on a number of core ANT concepts, such as negotiation, enrolment, alignment, black boxing and obligatory

point of passage. We see networks as created and sustained through inter-relational processes where various actants discuss, bargain and

negotiate to resolve matters of dispute and come to a mutual agreement (Callon, 1986a). From this perspective, we propose to shed light

on how actants that are already in a network enrol i.e. recruit, or co-opt new actants that will help them consolidate their network.

Successful networks of aligned interests are created through the enrolment of a sufcient body of allies, and the translation of their

interests so that they are willing to participate in particular ways of thinking and acting which maintain the network (Walsham, 1997).

Actants that are part of the same network are said to be aligned, i.e. to have aligned their interests with that of the rest of the network

(Callon, 1986a). A black box is an actant (that may be, e.g. a physical artefact, a computer system, a human grouping or a concept), which

other actants relate to without needing to understand or even be aware of its internal workings. Actants are typically being blackboxed

when they are considered to be overly complex, or when they have become so essential to the running of the network that they are taken

for granted (Callon & Latour, 1981). Obligatory points of passage are typically actants that have become indispensable to the smooth

functioning or the very existence of the network. They may act as intermediaries between networks or mediating elements between

network components (Law & Callon, 1992).

While the notion of agency usually is associated with human agency (Giddens, 1984), ANT and other post-humanist approaches call

attention to the sociomaterial nature of agency (Latour, 1987, 2005). Agency is not an inherent human quality, but a capacity realized

through the associations of actors (whether human or non-human), and thus relational, emergent and shifting (Orlikowski, 2007, p. 1438).

Suchman (2007, p. 267) goes one step further and proposes to respecify sociomaterial agency from a capacity intrinsic to singular actors to

an effect of practices that are multiply distributed and contingently enacted. In that sense, the core notions of ANT as outlined above are

supporting a sociomaterial investigation of agency. Enrolment and alignment take place between humans and non-humans when they

negotiate the purposes of networks of practice, and collaborate in creating, designing and developing those networks. Black-boxing and

obligatory points of passage encapsulate those elements in agency that relate to making artefacts and processes that have become so

established that they are perceived as immutable.

4. Method and sampling

In this study, we use an interpretive ethno-methodological approach, framing studies of work as a social activity (Maynard & Clayman,

1991; Psathas, 1995). The study has been designed as an explorative case study, i.e. a detailed examination of a particular context for

teaching practices (Yin, 1989). It is to be noted that commercial VLEs in Norway have been widely implemented all through the Norwegian

educational system and thereby becoming a ubiquitous tool (ITU monitor, 2009; Norway Opening Universities, 2009). We have therefore

included two sets of data, collected in the contexts of, respectively, primary schools and higher education, looking both at similarities and

differences when using the same kind of VLE (Fronter).

The rst dataset includes teaching staff in higher education, referred to as lecturers. The second dataset represents teaching staff in

primary schools, referred to as teachers. Interviews were conducted with teachers at three primary schools and lecturers at ve faculties

within an institution of higher education. We chose primary schools and higher education because they represent two widely different user

groups of VLE.

The primary school teachers were purposely selected from a governmental project called Learning networks1 whereby members of staff

at various state schools were given the opportunity to follow courses at a nearby college aiming at enhancing their ICT prociency. All three

schools are located in small municipalities close to a larger city and can be characterized as having limited experience in the didactic use of

ICT in classrooms. The strategy for selection of study participants was based on purposive selection criteria (Miles & Huberman, 1994;

Patton, 1990), by asking representatives of the academic management at each school to suggest teachers of diverse levels of ICT prociency

and engagement in VLE as actual candidates for interviews. A total of eight primary school teachers participated in the study. The eleven

informants from the higher education faculties were selected via recommendation (8 out of 11) or through response to an advert on the

institutions webpage (3 out of 11). The goal was to recruit educators that were involved in core teaching activities within their faculties and

were active VLE users, although some of them had relatively little interest in technology per se. All the teachers and lecturers approached for

this study accepted to participate, but two informants only participated in the rst interview and the log taking due to a heavy workload.

1

The national project Learning Networks was set up in order to strengthen the implementation of ICT in primary schools through communities of practice. The project

brings together teachers, school management, school district management and teacher education institutions.

788

M. Johannesen et al. / Computers & Education 59 (2012) 785792

The study was conducted over a period of one academic year. For each informant, data were gathered in three phases. In a rst phase, an

initial semi-structured interview based on an interview guide2 was conducted. The intention of this interview was to get insights into the

informants thoughts and attitudes with a minimal amount of predened questions. This rst interview lasted on average 1 h and was

followed up by self-reported personal log3 on activities and practices with VLE. The third phase consisted of a follow-up 1-h interview about

the documented experience from the log and the changes that occurred since the rst phase. The two interviews and the logging of teaching

practice were typically collected within a time span of three to six months, depending on the availability of the informants for a second

interview. A total of nineteen informants were interviewed for this study, eight primary school teachers (seven females and one male), and

eleven lecturers in higher education (six females and ve males). In addition, activities on the VLE at the three participating schools and the

ve faculties (Teacher Education, Engineering, Nursing, Social Studies and Health Sciences) were logged. The online logging activities were

performed by two of the three authors of this article. Those consisted of logging in to the VLE in use at the informants institutions, and

recording in detail what was done in terms of pedagogical activities, who participated in them (teachers/lecturers as well as students), how

long they lasted and how they were documented.

The interviews were all transcribed and coded with the computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software HyperRESEARCH

(ResearchWare Inc., Randolph, MA, USA). A list of codes was developed as the analysis went along, based on both the original research

question and the core notions of ANT, i.e. negotiation, enrolment, alignment, black boxing and obligatory point of passage. To retrieve and

categorize data, searches were carried out on the basis of terms that were considered relevant to the research question. The nal list of codes

entailed new, emerging, themes such as governance, efciency, and supporting professional practice, which appeared as recurrent in the

analysis of the data. The extracts from the interviews and the personal logs, that were located through those searches, formed the main basis

of the analysis.

5. Data analysis

In this section, we describe and discuss the ndings emerging from the data analysis. The data collected allowed us to identify a number

of teaching practices that had been developed over time with the use of the VLE. Some of those practices have been introduced deliberately,

while others have emerged unintentionally. With the help of a computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software, we identied a number

of key concepts that appeared to be of signicance to shed light on our research question. We then worked at gathering them in subgroups,

and three general themes emerged from this process: educational governance, teaching efciency and the professional practice.

5.1. The inuence of educational authorities and school management (governance)

In many cases the informants mention that the introduction of the VLE is the result of a managerial decision, both in higher education and

in primary schools. The top-down implementation of new technologies such as VLE seems to generally foster resistance among the staff, as

illustrated in the quote below:

There was much resistance [on my part]. Because I thought: argh!, one more thing one has to learn. And soon its out, and well be introduced to

something else again, and thats how it goes all the time. So I most of all want to postpone it as long as I can, and hope it will be gone before [I

start using it]. because then something else pops up, and then I would have managed to jump over one link in the chain.. [Lecturer 1]

Some informants report that the reason why they accepted to use the VLE is that they were encouraged or coerced by either students,

colleagues or managers, as the following quote exemplies:

I feel a strong pressure here. A strong pressure. [.]. Oh, and Im not one of those who say: yes, this is going to be fun!. No, well, Im not like

that. I have a computer at home, but no, isnt there anything else to do? [Teacher 9]

A story told by the same teacher illustrates how the management at her school expects constant online availability through the VLE.

Yesterday, for example, the principal came to me and said: Oh, didnt you know? One of your students is sick today. But you obviously havent

logged in and checked your mail. No, I hadnt and it was, like, 8:35 a.m. I try to be diligent [with checking my email regularly], but you dont

always [manage]. [Teacher 9]

In this case, we observe that a teacher encounters indirect pressure from a hierarchical superior, which she experiences as unjustied.

However, it is to be noted that some informants report having realized after a while that the VLE was more useful to their work than what

they had rst expected. In this sense the teachers consider the managerial pressure as a useful means to achieving appropriate and efcient

teaching and can see the relevance of the positive pressure to implement systems that bring about new teaching practice.

5.2. Managing students, parents and co-teachers (efciency)

Another key nding was the teachers and lecturers experience of empowerment vis--vis their own teaching tasks as being facilitated

by the VLE. Agency is particularly visible as far as improved communication and collaboration are concerned. Agency is also experienced as

the result of new work processes allowing increased exibility in terms of time and space and a closer follow-up of the students, especially

as far as response speed is concerned.

2

The interview guide covered the following topics: the informants actual use of VLEs, their attitudes towards VLEs, their former experience with VLEs, as well as the

pedagogical beliefs that they consider as fundamental for their teaching.

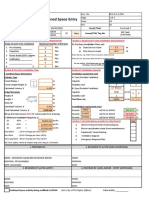

3

The informants were provided a standard form to register their actual use of the VLE as well as their reections on their own use of this technology. In particular, they

were asked to report the date and time of their activities on the VLE, a detailed description of those activities, and their own reections on whether they experienced the VLE

as supporting/encumbering existing teaching practice or inspiring them to implement new work practices.

M. Johannesen et al. / Computers & Education 59 (2012) 785792

789

One lecturer mentions that using the e-mail and news functions of the VLE provides her with a higher level of certainty as to what

information the students have received and when. Another lecturer highlights the systems capacity to follow closely students progress and

react when some appear to be on the verge of not completing their module. One of the lecturer reports that she uses the statistics function

of VLE to gain an overview of who among the students have accessed the online information and when, thereby rapidly getting an overview

of who has not performed the required assignments on time.

In a similar way, teachers at two of the three primary schools also report that they enjoy using multiple-choice questions (MCQs)

assignment tools for getting instant snapshots of students knowledge in a certain subject areas. Some higher education lecturers reports

that MCQs are used among students for efcient learning of a large and time-consuming curriculum as reported in earlier research from the

authors (Johannesen & Habib, 2010).

In the studied primary schools, the VLE is used to ensure that the parents get the information they need from the school at the right time

and to engage them in their childs learning. For example, one primary school teacher expresses that the VLE tool used to create digital

portfolios makes it easier to involve parents in their childrens learning processes:

The digital portfolios, just to give you an example from the class that I have, they go in all directions. Some put in very much and some put in very

little [into the portfolio]. [..] But the portfolio is denitely a source of inspiration, since it inspires the learners to be more active in their

conversations with the parents. [Teacher 5]

Informants from primary schools express that they appreciate the support that VLEs give to collegial collaboration, as stated by one teacher:

It is kind of making the work of the contact teacher easier. Because, earlier we got a sheet from one teacher and one from another, you know, and

then you [as a contact teacher] have to sit down and write it all down, or you have to collect them all [the sheets]. Now you have everything in

one document. And the subject-area teachers have to ll it in themselves. [Teacher 3]

Such VLE use supports independent production and distribution of the written evaluation form thereby reducing the workload of the

contact teacher. These practices all emphasize the ways the VLE support teachers/lecturers in making parts of their teaching more efcient

than they may have done without the VLE.

5.3. Supporting professional practice

The informants describe a range of pedagogical methods that reect their view of the required or preferred teaching philosophy at their

workplace. Issues of exibility and creativity, student collaboration and adaptive teaching are recurring themes in the data.

5.3.1. Flexibility and creative practice

Some lecturers consider the VLE to be a exible tool, which supports a creative approach towards designing and adjusting teaching and

learning tasks:

. half-way [through the lecture], if you take a 15-minute break, you can go in[to the VLE] and modify some of what you have in there, so when

you show it to the class on the whiteboard after the break, something else will appear. [You then can say:] A propos what we talked about

during the rst hour.. This I think is kind of fun. [Lecturer 10]

Another instance of VLE-supported creative practice may be found in the initiative taken at one of the faculties of the studied higher education

institution allow students to create multiple-choice tests for each other, thereby promoting a novel and somewhat entertaining approach to getting

familiar with the curriculum. In addition, some primary school teachers use the VLE to create questionnaires about a subject that is to be covered at

a later date, so as to increase the students awareness of the issues at hand and motivate them to learn more about them.

5.3.2. Student collaboration

The lecturers in higher education attribute several instances of increased student collaboration to the implementation of the VLE. A number of

lecturers express a wish to get their students to discuss online, and describe that they only partly succeed in creating satisfactory VLE-based

discussions. In addition, the VLE is used to support other modes of student collaboration. For example, the students are encouraged to create

and post questions for their co-students that will allow them to get a deeper understanding of curriculum content. Also, several courses are

organized in such a way that students provide written feedback to each others work. This type of peer assessment is popular both among lecturers

and students since it normally reduces the workload of the lecturers without reducing the amount of feedback the students get. Collaborative work

within the VLE is generally seen as increasing the students motivation and thereby the quality of their learning. For example, as described by one of

the lecturer, who introduced compulsory feedback activities that paved the road for new arenas for peer-student learning.

The students get a bit more curious. When they for example have an assignment they very often think thats the way it is, thats the way it

should be. But if they get to read some of the answers produced by some of their co-students, they realize that it doesnt need to be like this, it

can also be like that. The students share more with each other when they in a way are forced to, because otherwise, most people hang on tight to

their work. Theyd rather not give their own products to others. [.] The good thing is that I see that the students can more easily nd use in each

others knowledge and can thus develop further. [Lecturer 10]

5.3.3. Adaptive teaching

Most informants both in primary schools and higher education mention that their VLE allows for a closer student follow-up. In higher

education, this follow-up seems mainly to have administrative purposes. Conversely, primary school informants report that the VLE allows

them to create new, more individualized ways of teaching, that are adapted to the students needs in terms of pace or level. Examples of such

new ways of teaching may be a series of assignments that are meant to be solved in a particular order, where the students only reach

a higher level after having answered correctly all the questions from the previous level.

790

M. Johannesen et al. / Computers & Education 59 (2012) 785792

We design the tests in such a way that you [the learner] can have several attempts at them. We do want them to learn. We dont just give them

one chance, but we give them several chances. [Teacher 5]

Both in higher education and in primary schools, VLEs have been used to support the implementation of digital portfolios. In higher

education, portfolio assessment is one of many methods which aim to increase the quality of learning by promoting continuous feedback

from faculty members and co-students. In primary schools, national regulations on assessment have resulted in an overall implementation

of digital portfolio assessment, as expressed by one teacher;

It is the school that has decided that everyone is going to have a portfolio, a selection of works in the portfolio, which we then use actively when

we have the teacher-student-parent conference. [Teacher 5]

It appears from the interviews that although most primary school teachers take this way of assessment for granted (Johannesen, in press)

they rarely express any deep reection about why it is used. Most informants present the use of digital portfolios as a desirable element, but

say little about why it is benecial to learning. In that sense, it may be suggested that they generally see the implementation of portfolio

assessment as a goal in itself rather than a necessary step to achieve something else.

6. Discussion

Our data analysis has helped us identify a set of core stakeholders and a set of core artefacts, which may all be referred to as actants and

which are interrelated within webs of sociomaterial assemblages. Issues of governance, efciency and supporting professional practices

point towards the importance of studying the dynamic interrelationship between teaching practices and the use of VLEs as new spaces for

teaching and learning. As presented above there are both similarities and differences in the ways VLEs are integrated as part of teaching

practices in primary schools and in higher education, where new practices are more evident among primary school teachers. To understand

how such dynamic interrelationships between technology and human practices evolve, the concept of network is essential. Our analysis

shows that three main actor-networks emerge from the categories presented above, giving a more contextual understanding of the ndings

presented. In each of these networks, the agency of the teachers and lecturers is crucial in shaping and consolidating the network they form

together with other human and non-human actants. A rst actor-network is built around the educational expectations placed on teaching,

embedded in structures ranging from national policies to institutional routines. A second actor-network is assembled around the concern of

teaching and learning strategies. In this network the dominant idea is that pedagogical practice has to optimise the use of time and resources

for both the teachers/lecturers and for the students so as to bring about the best possible learning. A third actor-network can be found

around the pedagogical values and beliefs of educators, in particular those beliefs that are inspired by a socio-cultural perspective on learning.

The rst network nds its main anchor within the national and local expectations of how education is supposed to be organized. As noted

in the above subsection on The inuence of educational authorities and school management, the use of VLEs in primary schools is strongly

encouraged by the school owner (which governs all the state schools in the region). Similarly, as presented in the same subsection, it is the

central administration of the higher education institution that decided to implement the VLE throughout the organisation. In ANT terms, we

can say that a certain amount of negotiation and purposive breakdown of the existing pockets of resistance have accompanied the VLE

implementations. Adaptive teaching and portfolio assessment gure among the national requirements that all primary schools have to full.

The Norwegian Quality Reform of Higher Education aimed at unifying educational procedures, making the educational system more efcient and giving a central place to student learning. Both in primary school and in higher education, the ndings reveal that the VLE acts as

an allied to the governing body as it enrols the teachers and lecturers into adhering to the governing bodys general policies. However, there

are no signs of negotiation in primary schools, uncovering a lack of questioning of the national and local policies in terms of whether they

represent good teaching practices. In particular, the ndings suggest that the idea of digital portfolio assessment as supporting good

teaching practices has somewhat been blackboxed, i.e. none of the informants seem to feel the need to cross-examine its well-foundedness.

In other words, their relational agency is primarily shaped by technological and organisational matters.

As presented in the above subsection on Managing students, parents and co-teachers, efciency has been a key motivation for the

introduction and implementation of VLEs. In one instance, the school management explicitly enrolled the VLE in their quest to build a more

effective parent-teacher dialogue, for example when formalizing constant online availability via the VLE. It can be suggested that such an

expectation is a central element in a process of setting up an obligatory point of passage for the teachers, presumably in such a way that it

becomes blackboxed. However, one of the teachers questions the necessity of such a practice, thereby opening the black box and destabilizing the actor-network, at least to some extent.

In this network the educators act in relation to national and local governance and the VLE emerges as an enrolling sociomaterial agent for

educational authorities. The procedures that are implemented in the VLE, such as time schedules, daily news, e-mail and evaluation forms,

constitute a new sociomaterial network. The educators practice with VLE technology, albeit more or less reluctant, generates a network

effect that can be described as a reication of these procedures. As in the case where a school principal expected the teacher to have read the

e-mail before class, the sociomaterial nature of using the VLE enrols educators into a standardized practice that is set by political and

managerial objectives. There are, however, also indications that this new sociomaterial network brings the educators and the inscribed

features of the VLE into a state of alignment, at least when the educators happen to experience VLE use as benecial. We might say that the

educators practice is materially recongured, and enrolled into a network promoting standardized practice (Murdoch, 1998).

The second network is formed around the idea that VLEs can support good learning and teaching strategies. In particular, VLEs act as

allies in the educators strategies to convey information efciently and accurately to the students. They also full a role as allied in that they

allow the teachers/lecturers to control how much and when their students access the information that they have published online. A VLE is

a crucial actant in enrolling the students into various kinds of study practices that are deemed to be both efcient in terms of resource use

and advantageous to the students, for example when promoting self-supported learning. In addition, in primary schools, the teachers use

VLEs to support behaviouristic-oriented training, for example when using multiple-choice questionnaires to repeat the curriculum. In this

network educators and students experience the VLE as an allied in striving to manage their daily workload. Herein, the educators needs

essentially correspond to what the technology can afford, thereby creating an environment with a largely balanced sociomaterial agency.

M. Johannesen et al. / Computers & Education 59 (2012) 785792

791

The efcacy dimension of the VLE use increases the educators capacity to carry out their teaching duties in a manner that fulls their

overall educational goals. The material structures of the VLE that allow educators to efciently reach students and parents, and that ensure

that the information provided is timely and appropriate are strongly aligned with the daily struggle of tting teaching practice into an

acceptable temporal and nancial framework. The educators statements on how they use MCQs for peer-student training and knowledgemapping indicate an emerging sociomaterial agency. The tools at hand generate new practice that is the effect of specic conguration of

human and non-human entities, striving to improve teaching and learning processes and their outcomes.

Another instance of sociomaterial agency is the teachers capacity to enrol parents into student learning. The VLE as a tool for

communication independent of time and space nds its place in the long-lasting endeavour of engaging parents into their childrens

schooling. This is an example of how agency is supported by non-humans. The VLE as a collaborative tool also meets the new requirements

for assessment (Johannesen, in press). As stated by several informants, the simplication of the process of making and communicating

written evaluations exemplies how the sociomateriality of VLE use is constitutive, shaping the possibilities of everyday organizing.

The third network can be seen as encompassing various actors around the idea of student-oriented teaching and learning and is strongly

inuenced by commonly accepted pedagogical values and beliefs. As indicated in the above subsection on Supporting professional practice,

most higher education informants mention student collaboration as a central teaching and learning strategy. They use the VLE as an allied to

design more engaging teaching practices and thereby enrol the students into a socio-cultural approach to learning. In primary schools, the

focus is not on collaboration but on individualized student-oriented approaches, including portfolio assessment. It is interesting to note that

the idea of portfolio assessment is somewhat blackboxed, as the informants do not mention any particular reason to use this way of

assessment other than it has been decided from higher places. It seems that the agency of educators is strongly negotiated through the

various functionalities of the VLE as a tool, thereby bringing about a sociomaterial network effect dominated by the technology. In this

network of professional practice, the educators and the VLE go through processes of mutual negotiation and those on-going processes

contribute to shaping the underlying pedagogical values and beliefs inscribed in teaching practice.

Another interesting nding from the data is that lecturers report increased student collaboration and improved opportunities to perform

adaptive teaching. The case of students that design their own questions for exams or give each other feedback on written assignments

exemplies how people, in tandem with material objects, are constantly transforming their social world and material environment,

creating and learning new knowledge as they go (Fox, 2009, p. 42). In the case of portfolio use, the higher education data indicate a high

degree of implementation of those educational principles that further collaboration as central to learning. Those principles are inscribed into

the system. Primary school practice reveals a transformation towards another network, namely that of educational governance on

assessment. Among the heterogeneous networks at play the inscribed materiality of digital portfolios as formative assessment tools seems

to be losing in negotiation with networks dominated by educational standards (governance) and efciency of teaching activities. This

indicates that there is a difference between stabilization within a network, and stabilization between networks (Star, 1991).

In this discussion section, we have seen that sociomaterial agency is at the core of the forming and development of actor-networks in

primary schools and higher education, but with various degrees of balance. The ndings support Suchmans (2007, p. 267) claim that [t]he

capacity for action is relational, dynamic and collective rather than inherent in specic network elements is of particular relevance to the

study of learning and teaching practices with VLE.

7. Conclusion

In this article, we have identied three major types of actor-networks that are relevant to processes of agency in the pedagogical practice

of teachers and lecturers using VLEs. Within those networks we can distinguish two recurrent and overlapping themes. The rst theme is

that of the very sociomateriality of teaching practice with VLEs. The second is that of power relations that may be intensied by the use of

VLEs, which are presumably signicantly related to the ubiquitous nature of VLEs as both material and social. Within those two themes, the

concept of agency emerges as a central one, both because VLEs allow teachers and lecturers to enact their pedagogical beliefs into their daily

practice and because they nd themselves in situations that are dictated by VLE use and that have major consequences onto their practice.

Our data suggest that we can describe a wide spectre of practices, ranging from those that are explicitly unwanted and resisted to those that

are explicitly accepted. Between those two extremes, we have identied a large number of nuances, including all the practices that have

been implicitly accepted and those that were simply not resisted when they emerged. As argued for in this article, we also believe that it is

important to compare and contrast practices of using digital technologies on different levels of the education system to better plan future

strategies of implementation and use at national, regional and local levels.

Common to all the identied practices are the more or less explicit sociomaterial network effects. The same tool and, to some extent, the

same functionalities of these tools support and challenge the agency of teaching practice. The inuence on the network of teaching practice

is dependent on the actors capacity to express in ones own language what others say and want, why they act in the way they do and how

they associate with each other; it is to establish oneself as a spokesman (Callon, 1986a, p. 223), whether the actor is human or non-human.

At the end of the process, if it is successful, only voices speaking in unison will be heard (ibid).

Due to the substantial role that VLEs have within the educational systems of a wide range of countries, it is necessary to increase our

understanding of how such tools inuence the pedagogical practices of teachers and lecturers. As discussed in this article the use of VLEs in

Norwegian education is embedded in different ways in educational practices, and interwoven within a complex web of regulations and

more or less explicit expectations from higher education management and school owners. The existence and ubiquitous nature of those

tools in the educational landscape has consequences that, from what the data presented in the article indicates, is often undercommunicated, presumably due to a tradition of tacit acceptance of a certain type of pedagogical philosophy and practices in educational

settings. In particular, many primary school teachers feel ambivalent and insecure in their use of such technological tools (Erstad & Quale,

2009), which can potentially be detrimental to their feeling of ownership of the pedagogical practice developed with and around those tools.

As expressed in this article, we believe sociomaterial approaches to technology-based and technology-supported educational practices are

important in moving this eld of research forward.

This research has been conducted within the realm of a particular national landscape, and in a limited number of institutions. It is also

explorative of qualitative in nature with a focus on trying to make sense of a complex eld with a large number of stakeholders. It has

792

M. Johannesen et al. / Computers & Education 59 (2012) 785792

therefore no intention to provide universal or general claims on the topic of VLE use in teaching practice. The insights it provides into the

research area may be enriched through further research, for example including other types of stakeholders, e.g. students, technical staff,

software developers. Such additional insights will nd their natural place in an ANT-informed approach.

References

Alvarez, I., Guasch, T., & Espasa, A. (2009). University teacher roles and competencies in online learning environments: a theoretical analysis of teaching and learning

practices. European Journal of Teacher Education, 32(3), 321336.

Becta ICT Research. (2004). What the research says about virtual learning environments in teaching and learning. British Educational Communications and Technology Agency.

Britain, S., & Liber, O. (1999). A framework for pedagogical evaluation of virtual learning environments (No. 41). JISC Technology Application Programme.

Callon, M. (1986a). The sociology of an actor-network: the case of the electric vehicle. In M. Callon, J. Law, & A. Rip (Eds.), Mapping the dynamics of science and technology.

Sociology of science in the real world (pp. 1934). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Callon, M. (1986b). Some elements of a sociology of translation: domestication of the scallops and the shermen of St Brieuc Bay. In J. Law (Ed.), Power, action and belief. A new

sociology of knowledge?. Sociological Review Monograph, Vol. 32 (pp. 196233). London: Routledge & Kegan.

Callon, M., & Latour, B. (1981). Unscrewing the big Leviathans: how do actors macrostructure reality. In K. Knorr, & A. Cicourel (Eds.), Advances in social theory and methodology: Toward an integration of micro and macro sociologies (pp. 277303). London: Routledge.

Callon, M., Law, J., & Rip, A. (1986). How to study the force of science. In M. Callon, J. Law, & A. Rip (Eds.), Mapping the dynamics of science and technology. Sociology of science in

the real world (pp. 315). Basingstoke: Macmillan.

Castor, T., & Cooren, F. O. (2006). Organizations as hybrid forms of life. Management Communication Quarterly, 19(4), 570600.

Coyne, R. (2010). The tuning of place: Social spaces and pervasive digital media. Boston: MIT Press.

Edwards, R. (2009). Introduction. Life as a learning context. In R. Edwards, G. J. J. Biesta, & M. Thorpe (Eds.), Rethinking context for learning and teaching. Communities, activities

and networks. New York: Routledge.

Erstad, O., & Quale, A. (2009). National policies and practices on ICT in education: Norway. In T. Plomp, R. E. Anderson, N. Law, & A. Quale (Eds.), Cross-national information and

communication technologyPolicies and practices in education (pp. 551568). Charlotte, North Carolina: Information Age Publishing, Revised Second Edition.

Fenwick, T. (2010). Re-thinking the thing. Sociomaterial approaches to understanding and researching learning in work. Journal of Workplace Learning, 22(1/2), 104116.

Fenwick, T., & Edwards, R. (2010). Actor-network theory in education. London: Routledge.

Fox, S. (2009). Contexts of teaching and learning. An actor-network view of the classroom. In R. Edwards, G. J. J. Biesta, & M. Thorpe (Eds.), Rethinking contexts for learning and

teaching: Communities, activities and networks (pp. 3143). London: Routledge.

Giddens, A. (1984). The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Hitchings, R. (2003). People, plants and performance: on actor network theory and the material pleasures of the private garden. Social & Cultural Geography, 4(1), 99.

Holield, R. (2009). Actor-network theory as a critical approach to environmental justice: a case against synthesis with urban political ecology. Antipode, 41(4), 637658.

Holland, D. C., Lachicotte, W., Jr., Skinner, D., & Cain, C. (1998). Identity and agency in cultural worlds. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press.

ITU monitor. (2009). The digital state of affairs in Norwegian schools 2009 [Skolens digital tilstand]. National Network for IT-Research and Competence in Education (ITU).

Johannesen, M. The role of virtual learning environment in a primary school context. The inscription of assessment practices. British Journal of Educational Technology, in press.

Johannesen, M., & Habib, L. (2010). The role of professional identity in patterns of use of multiple-choice assessment tools. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 19(1), 93109.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. (1988). The pasteurization of France. Cambridge, Mass and London, England: Harvard University Press.

Latour, B. (1992). Where are the missing masses? The sociology of a few mundane artefacts. In W. E. Bijker, & J. Law (Eds.), Shaping technology/building society: Studies in

sociotechnical change (pp. 225258). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Latour, B. (1993). We have never been modern. Hemell Hempstead: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Latour, B. (2005). Reassembling the social. An introduction to actor-network-theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Law, J. (1992). Notes on the theory of actor-network: ordering, strategy, and heterogeneity. Systems Practice, 5, 379393.

Law, J., & Callon, M. (1992). The life and death of an aircraft: a network analysis of technical change. In W. E. Bijker, & J. Law (Eds.), Shaping technology/building society: Studies

in sociotechnical change (pp. 2152). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lazakidou, G., & Retalis, S. (2010). Using computer supported collaborative learning strategies for helping students acquire self-regulated problem-solving skills in mathematics. Computers & Education, 54(1), 313.

Limniou, M., & Smith, M. (2010). Teachers and students perspectives on teaching and learning through virtual learning environments. European Journal of Engineering

Education, 35(6), 645653.

Lonn, S., & Teasley, S. D. (2009). Saving time or innovating practice: investigating perceptions and uses of learning management systems. Computers & Education, 53(3), 686

694.

Maynard, D. W., & Clayman, S. E. (1991). The diversity of ethnomethodology. Annual Review of Sociology, 17(1), 385418.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mueller, D., & Strohmeier, S. (2011). Design characteristics of virtual learning environments: state of research. Computers & Education, 57(4), 25052516.

Mulcahy, D., & Perillo, S. (2011). Thinking management and leadership within colleges and schools somewhat differently: a practice-based, actor-network theory perspective.

Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 39(1), 122145.

Murdoch, J. (1998). The spaces of actor-network theory. Geoforum, 29(4), 357374.

Murdoch, J. (2001). Ecologising sociology: actor-network theory, co-construction and the problem of human exemptionalism. Sociology, 35(1), 111133.

Nespor, J. (1994). Knowledge in motion: Space, time, and curriculum in undergraduate physics and management. London: Falmer Press.

Norway Opening Universities. (2009). ICT monitor in higher education. [Digital utfordringer i hyerer utdanning. Norgesuniversitetets IKT-monitor]. Norway Opening Universities.

Report no 1/2009.

Orlikowski, W. J. (2007). Sociomaterial practices: exploring technology at work. Organization Studies, 28(9), 14351448.

Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods (2nd ed.). Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Psathas, G. (1995). Talk and social structure and studies of work. Human Studies, 18(2/3), 139155.

Ruming, K. (2009). Following the actors: mobilising an actor-network theory methodology in geography. Australian Geographer, 40(4), 451469.

Samarawickrema, G., & Stacey, E. (2007). Adopting web-based learning and teaching: a case study in higher education. Distance Education, 28(3), 313333.

Schn, D. A. (1983). The reective practitioner: How professionals think in action. New York: Basic Books.

Star, S. L. (1991). Power, technologies and the phenomenology of conventions: on being allergic to onions. InLaw, J. (Ed.). (1991). A sociology of monsters? Essays on power,

technology and domination, Vol. 38 (pp. 2646). London: Routledge.

Suchman, L. A. (2007). Human-machine recongurations: Plans and situated actions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sutherland, R., Robertson, S., & John, P. (2008). Improving classroom learning with ICT. London: Routledge.

Turnbull, M. (2005). Student teacher professional agency in the practicum. Asia-Pacic Journal of Teacher Education, 33(2), 195208.

Walsham, G. (1997). Actor-network theory and IS research: Current status and future prospects. London: Chapman and Hall.

Weiss, J. (2006). Introduction: virtual learning and learning virtually. In J. Weiss, J. Nolan, J. Hunsinger, & P. Trifonas (Eds.), The international handbook of virtual learning

environments. Dordrecht: Springer.

Weiss, J., Nolan, J., Hunsinger, J., & Trifonas, P. (Eds.). (2006). The international handbook of virtual learning environments. Dordrecht: Springer.

Westergren, U. H. (2011). Disentangling sociomateriality. An exploration of remote monitoring systems in interorganizational networks. Ume: Ume University.

Yaneva, A. (2009). Making the social hold: towards an actor-network theory of design. Design and Culture, 1(3), 273288.

Yin, R. K. (1989). Case study research: Design and methods. Newbury Park: Sage.

Young, D., Borland, R., & Coghill, K. (2010). An actor-network theory analysis of policy innovation for smoke-free places: understanding change in complex systems. American

Journal of Public Health, 100(7), 12081217.

You might also like

- Service Manual 900 OG Factory 16V M85-M93Document572 pagesService Manual 900 OG Factory 16V M85-M93Sting Eyes100% (1)

- mf8240 160824142620 PDFDocument698 pagesmf8240 160824142620 PDFArgopartsNo ratings yet

- The Crime of Galileo - de Santillana, Giorgio, 1902Document372 pagesThe Crime of Galileo - de Santillana, Giorgio, 1902Ivo da Costa100% (2)

- Doing - Development Research 6NiTY9H5fkDocument337 pagesDoing - Development Research 6NiTY9H5fkClaudia Jaramillo MartínezNo ratings yet

- Scor Overview v2 0Document62 pagesScor Overview v2 0Grace Jane Sinaga100% (1)

- Understanding Educational Technology DefinitionsDocument17 pagesUnderstanding Educational Technology DefinitionsWilz LacidaNo ratings yet

- Ventilation Plan For Confined Space EntryDocument9 pagesVentilation Plan For Confined Space EntryMohamad Nazmi Mohamad Rafian100% (1)

- Module 1-Theories of Educational TechnologyDocument32 pagesModule 1-Theories of Educational TechnologyJoevertVillartaBentulanNo ratings yet

- Theoretical FrameworkDocument12 pagesTheoretical FrameworkJP Ramos Datinguinoo100% (1)

- Viewing Mobile Learning From A Pedagogical Perspective: A, A B ADocument17 pagesViewing Mobile Learning From A Pedagogical Perspective: A, A B AMarco SantosNo ratings yet

- Contextualised Media for Learning: A Technical FrameworkDocument11 pagesContextualised Media for Learning: A Technical FrameworkBilel El MotriNo ratings yet

- Mapping Pedagogy and Tools For Effective by Conole Dyke 2004Document17 pagesMapping Pedagogy and Tools For Effective by Conole Dyke 2004Kangdon LeeNo ratings yet

- Technology, Pedagogy and Education Reflections On The Accomplishment of What Teachers Know, Do and Believe in A Digital Age LovelessDocument17 pagesTechnology, Pedagogy and Education Reflections On The Accomplishment of What Teachers Know, Do and Believe in A Digital Age LovelessTom Waspe Teach100% (1)

- The Potential of Developmental Work Research As A Professional Learning Methodology in Early Childhood EducationDocument11 pagesThe Potential of Developmental Work Research As A Professional Learning Methodology in Early Childhood EducationAini Fazlinda NICCENo ratings yet

- 2006 P.mishra&Koehler - Technological Pedagogical Content KnowledgeDocument38 pages2006 P.mishra&Koehler - Technological Pedagogical Content KnowledgeAnger Phong NguyễnNo ratings yet

- The Socio-Cultural Ecological Approach TDocument2 pagesThe Socio-Cultural Ecological Approach TFaraz MasoodNo ratings yet

- Digital Learning Ecosystem by Nancy Slawski & Nancy ZomerDocument10 pagesDigital Learning Ecosystem by Nancy Slawski & Nancy ZomerNancy SlawskiNo ratings yet

- A Barrier Framework For Open E-Learning in Public AdministrationsDocument3 pagesA Barrier Framework For Open E-Learning in Public AdministrationsMustafamna Al SalamNo ratings yet

- Perspectives on personal learning environments held by vocational studentsDocument8 pagesPerspectives on personal learning environments held by vocational studentsYulong WangNo ratings yet

- PP - Transparency in Cooperative Online Education - IRRODL - 22pgDocument22 pagesPP - Transparency in Cooperative Online Education - IRRODL - 22pgGiancarlo ColomboNo ratings yet

- The Use of Cyper Study 23Document13 pagesThe Use of Cyper Study 23vinhb2013964No ratings yet

- Mobile Learning Conference IADIS 2010 Doctoral PaperDocument4 pagesMobile Learning Conference IADIS 2010 Doctoral PaperNicola Beddall-HillNo ratings yet

- Activity Theory and Qualitative Research in Digital Domains: Cecile SamDocument9 pagesActivity Theory and Qualitative Research in Digital Domains: Cecile SamEmad OmidpourNo ratings yet

- A Framework For Interaction and Cognitive Engagement in Connectivist Learning ContextsDocument21 pagesA Framework For Interaction and Cognitive Engagement in Connectivist Learning ContextsAnonymous XoQ2YTNma3No ratings yet

- TPACK Handbook2 IntroDocument14 pagesTPACK Handbook2 IntroThomas RoumeliotisNo ratings yet

- A Theory For Elearning: Pre-Discussion PaperDocument10 pagesA Theory For Elearning: Pre-Discussion PaperSahar SalahNo ratings yet

- Using Log Variables in A Learning Management System To Evaluate Learning Activity Using The Lens of Activity TheoryDocument18 pagesUsing Log Variables in A Learning Management System To Evaluate Learning Activity Using The Lens of Activity TheoryNaila AshrafNo ratings yet

- Collaboration Levels in Asynchronous Discussion Forums: A Social Network Analysis Approach Cecilia Luhrs & Lewis Mcanally-SalasDocument16 pagesCollaboration Levels in Asynchronous Discussion Forums: A Social Network Analysis Approach Cecilia Luhrs & Lewis Mcanally-SalasLewis McAnallyNo ratings yet

- The Principles of Learning and Teaching PoLT PDFDocument20 pagesThe Principles of Learning and Teaching PoLT PDFMindy Penat PagsuguironNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument10 pages1 PBLevania MirandaNo ratings yet

- Data-Driven Instruction in The Classroom: January 2015Document5 pagesData-Driven Instruction in The Classroom: January 2015Kaberia MberiaNo ratings yet

- (8-12) Developing Teaching Material For E-Learning EnvironmentDocument5 pages(8-12) Developing Teaching Material For E-Learning EnvironmentiisteNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Teacher EducationDocument20 pagesEuropean Journal of Teacher EducationMircea RaduNo ratings yet

- 2012 ManchesDocument15 pages2012 ManchesPsy DaddyNo ratings yet

- Revising The Framework of Knowledge Ecologies HowDocument26 pagesRevising The Framework of Knowledge Ecologies HowazuredianNo ratings yet

- Dron Participatory Orchestration AISpreprintDocument41 pagesDron Participatory Orchestration AISpreprintAkhmada Khasby Ash ShidiqyNo ratings yet

- Estágio Na ComunicaçãoDocument17 pagesEstágio Na ComunicaçãoAline GonçalvesNo ratings yet

- Activate English Learning with AR U-Learning SystemDocument13 pagesActivate English Learning with AR U-Learning Systemsome oneNo ratings yet

- The Principles of Learning and Teaching PoLT PDFDocument20 pagesThe Principles of Learning and Teaching PoLT PDFWedo Nofyan FutraNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Internasional IPA Terpadu - Kelompok 3Document16 pagesJurnal Internasional IPA Terpadu - Kelompok 3Syifa Sadiyah.No ratings yet

- PrePrint EdarxivDocument54 pagesPrePrint EdarxivRoyce Anne Marie LachicaNo ratings yet

- A Brief History of Mobile Seamless Learning: September 2015Document43 pagesA Brief History of Mobile Seamless Learning: September 2015Bilel El MotriNo ratings yet

- Blended Learning With Everyday Technologies To Activate Students' Collaborative LearningDocument12 pagesBlended Learning With Everyday Technologies To Activate Students' Collaborative LearningJanika NiitsooNo ratings yet

- Handbook of Technological. Knowledge For: Pedagogical Content EducatorsDocument14 pagesHandbook of Technological. Knowledge For: Pedagogical Content Educatorsabusroor2008No ratings yet

- Investigating Patterns of Interaction inDocument17 pagesInvestigating Patterns of Interaction inmprietofNo ratings yet

- Network Literature ReviewDocument7 pagesNetwork Literature Reviewafmzahfnjwhaat100% (1)

- Dr. S. Wheeler Personal Technologies in Education - Issues, Theories and DebatesDocument12 pagesDr. S. Wheeler Personal Technologies in Education - Issues, Theories and DebatesKaren TriquetNo ratings yet

- Downes (2007)Document25 pagesDownes (2007)rashid khanNo ratings yet

- Using Systems Thinking To Leverage Technology For School ImprovementDocument24 pagesUsing Systems Thinking To Leverage Technology For School ImprovementCindyVillalbaDiazNo ratings yet

- Student Teachers Socialization Development by Teaching Blog: Reflections and Socialization StrategiesDocument12 pagesStudent Teachers Socialization Development by Teaching Blog: Reflections and Socialization StrategiesRishina DeviNo ratings yet

- Si 2020 100437Document11 pagesSi 2020 100437dianjoshuaNo ratings yet

- Pedagogik Transformatif PDFDocument14 pagesPedagogik Transformatif PDFEga Puji RahayuNo ratings yet

- Designing Learning Environments Improving Social Interactions: Essential Variables For A Virtual Training SpaceDocument5 pagesDesigning Learning Environments Improving Social Interactions: Essential Variables For A Virtual Training SpaceIulia CaileanNo ratings yet

- The Contextualization in The Teaching Physics Through of Instruments of The Educational Robotics: Analysis of Activities by Verisimilar PraxeologyDocument14 pagesThe Contextualization in The Teaching Physics Through of Instruments of The Educational Robotics: Analysis of Activities by Verisimilar PraxeologyschivaniNo ratings yet

- Why Hasn't Technology Disrupted Academics' Teaching Practices? Understanding Resistance To Change Through The Lens of Activity TheoryDocument16 pagesWhy Hasn't Technology Disrupted Academics' Teaching Practices? Understanding Resistance To Change Through The Lens of Activity TheoryMagnun BezerraNo ratings yet

- Making Mobile Learning Work: Student Perceptions and Implementation FactorsDocument24 pagesMaking Mobile Learning Work: Student Perceptions and Implementation FactorsJuan BendeckNo ratings yet

- A Conceptual Framework For Task and Tool Personalisation in IS EducationDocument17 pagesA Conceptual Framework For Task and Tool Personalisation in IS EducationroziahmaNo ratings yet

- Constructivism, Instructional Design, and Technology Implications For Transforming Distance LearningDocument12 pagesConstructivism, Instructional Design, and Technology Implications For Transforming Distance LearningMarcel MaulanaNo ratings yet

- E LearningDocument9 pagesE LearningSalma JanNo ratings yet

- Designing Opportunities Transformation Emerging TechnologiesDocument10 pagesDesigning Opportunities Transformation Emerging Technologiesapi-316863050No ratings yet

- Workshops As A Research MethodologyDocument12 pagesWorkshops As A Research MethodologyReshmi VarmaNo ratings yet

- Wikis A Collective Approach To LanguageDocument20 pagesWikis A Collective Approach To LanguageMourad Diouri100% (1)

- The Analysis of Complex Learning EnvironmentsDocument24 pagesThe Analysis of Complex Learning Environmentspablor127100% (1)

- ArticleDocument12 pagesArticleDalia LeonNo ratings yet

- MOOCs: Expectations and RealityDocument211 pagesMOOCs: Expectations and Realitythe_shoveller100% (1)

- MOOCs: Expectations and RealityDocument211 pagesMOOCs: Expectations and Realitythe_shoveller100% (1)

- Social Post Disaster 1Document11 pagesSocial Post Disaster 1Claudia Jaramillo MartínezNo ratings yet

- The Externalities of Strong Social Capital: Post-Tsunami Recovery in Southeast IndiaDocument20 pagesThe Externalities of Strong Social Capital: Post-Tsunami Recovery in Southeast IndiaClaudia Jaramillo MartínezNo ratings yet

- Communication Systems Engineering John G Proakis Masoud Salehi PDFDocument2 pagesCommunication Systems Engineering John G Proakis Masoud Salehi PDFKatie0% (2)

- Usg Sheetrock® Brand Acoustical SealantDocument3 pagesUsg Sheetrock® Brand Acoustical SealantHoracio PadillaNo ratings yet

- QO™ Load Centers - QO124M200PDocument4 pagesQO™ Load Centers - QO124M200PIsraelNo ratings yet

- IEC 60793-1-30-2001 Fibre Proof TestDocument12 pagesIEC 60793-1-30-2001 Fibre Proof TestAlfian Firdaus DarmawanNo ratings yet

- What Happens To Load at YieldingDocument14 pagesWhat Happens To Load at YieldingWaqas Anjum100% (2)

- Worksheet Chapter 50 Introduction To Ecology The Scope of EcologyDocument2 pagesWorksheet Chapter 50 Introduction To Ecology The Scope of EcologyFernando CastilloNo ratings yet

- 5 & 6 Risk AssessmentDocument23 pages5 & 6 Risk AssessmentAzam HasanNo ratings yet

- Snel White Paper 2020Document18 pagesSnel White Paper 2020Zgodan NezgodanNo ratings yet

- Maths ReportDocument3 pagesMaths ReportShishir BogatiNo ratings yet

- Installation Procedure for Castwel Supercast-II CastableDocument3 pagesInstallation Procedure for Castwel Supercast-II CastableRAJKUMARNo ratings yet

- Troubleshooting Lab 1Document1 pageTroubleshooting Lab 1Lea SbaizNo ratings yet

- Product PlanningDocument23 pagesProduct PlanningGrechen CabusaoNo ratings yet

- 3 To 8 Decoder in NGSPICEDocument14 pages3 To 8 Decoder in NGSPICEJaydip FadaduNo ratings yet

- Functional Molecular Engineering Hierarchical Pore-Interface Based On TD-Kinetic Synergy Strategy For Efficient CO2 Capture and SeparationDocument10 pagesFunctional Molecular Engineering Hierarchical Pore-Interface Based On TD-Kinetic Synergy Strategy For Efficient CO2 Capture and SeparationAnanthakishnanNo ratings yet

- RDSCM HowTo GuideDocument17 pagesRDSCM HowTo GuideEric LandryNo ratings yet

- Starting and Configuring Crontab in CygwinDocument2 pagesStarting and Configuring Crontab in CygwinSamir BenakliNo ratings yet

- Six Sigma MotorolaDocument3 pagesSix Sigma MotorolarafaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6 (Latest) - Value Orientation and Academic AchievementDocument21 pagesChapter 6 (Latest) - Value Orientation and Academic AchievementNur Khairunnisa Nezam IINo ratings yet

- Rexroth HABDocument20 pagesRexroth HABeleceng1979No ratings yet

- Design Prof BlankoDocument11 pagesDesign Prof BlankoAousten AAtenNo ratings yet

- Suggested For You: 15188 5 Years Ago 20:50Document1 pageSuggested For You: 15188 5 Years Ago 20:50DeevenNo ratings yet

- ReedHycalog Tektonic™ Bits Set New RecordsDocument1 pageReedHycalog Tektonic™ Bits Set New RecordsArifinNo ratings yet

- Ethics UNAM IsakDocument74 pagesEthics UNAM IsakIsak Isak IsakNo ratings yet

- Appendix 1c Bridge Profiles Allan TrussesDocument43 pagesAppendix 1c Bridge Profiles Allan TrussesJosue LewandowskiNo ratings yet

- 3D Printing Seminar REPORT-srijanDocument26 pages3D Printing Seminar REPORT-srijanSrijan UpadhyayNo ratings yet