Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Urban Policies On Diversity in Rotterdam

Uploaded by

fer09mataOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Urban Policies On Diversity in Rotterdam

Uploaded by

fer09mataCopyright:

Available Formats

Governing Urban Diversity: Creating Social Cohesion, Social Mobility and Economic Performance in Todays

Hyper-diversified Cities

Urban Policies on Diversity in Rotterdam, The Netherlands

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Work package 4:

Assessment of Urban Policies

Deliverable nr.:

D 4.1

Lead partner:

Partner 6 (UCL)

Authors:

Anouk Tersteeg, Ronald van Kempen, Gideon Bolt

Nature:

Report

Dissemination level: PP

Status:

Final version

Date:

4 August 2014

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

This project is funded by the European Union under the 7th Framework Programme;

Theme: SSH.2012.2.2.2-1; Governance of cohesion and diversity in urban contexts

Grant agreement: 319970

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

To be cited as: Tersteeg, A.K., R. van Kempen & G.S. Bolt (2013), Urban Policies on Diversity in Rotterdam,

The Netherlands. Utrecht: Faculty of Geosciences, Utrecht University.

This report has been put together by the authors, and revised on the basis of the valuable comments, suggestions,

and contributions of all DIVERCITIES partners.

The views expressed in this report are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of

European Commission.

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

Contents

1.

Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 4

2.

Overview of political system and governance structure for diversity in Rotterdam ................ 4

2.1

The political system and governance structure for urban diversity policy ........................................................ 4

2.2

Key shifts in national approaches to policy over migration, citizenship and diversity...................................... 7

3.

Policy strategies on diversity in Rotterdam ................................................................................... 10

3.1 Dominant governmental discourses of urban policy and diversity ................................................................ 12

3.2 Non-governmental views on diversity policy ............................................................................................... 27

4.

Conclusions ........................................................................................................................................ 30

References.................................................................................................................................................... 32

Appendix I. List of policy actors interviewed ........................................................................................ 35

Appendix II. List of policy documents analysed ................................................................................... 36

Appendix III. Analysis of policy documents ......................................................................................... 37

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

1. Introduction

This report examines the current approaches in policies with respect to diversity for the city of

Rotterdam, the Netherlands. As a background, we first provide an overview of the national

political system and the governance structure for diversity in Rotterdam. We examine which

actors - both governmental and non-governmental and at multiple levels of scale - are involved in

the governance of diversity in Rotterdam. In addition, we give a short outline of key shifts in

national policy discourses on diversity, citizenship and in-migration since the 1980s. Second, we

analyse dominant governmental discourses on urban policy and diversity. Therefore, we examine

how diversity is addressed in the most significant documents that deal with diversity in

Rotterdam. On the basis of qualitative interviews, we also examine how governmental policy

actors in the city understand the policies. Third, we also examine non-governmental views on

diversity policy. Amongst others, we identify the importance of diversity as a policy issue, and the

meaning, objectives and targets of the relevant policies, in different important fields, such as

integration, housing, education, and work.

We find that present policy in Rotterdam pays little attention to diversity, that diversity is mostly

understood as a matter of ethnicity, and that it is seen as a problem rather than an asset. Several

policy actors have expressed their concern about the mainstream1 nature of the local policies

pursued by the municipality as they believe that it runs the risk of overlooking the specific needs

of vulnerable social groups. Several examined policies were found to be rooted in an

assimilationalist discourse: the policies are aimed at all Rotterdammers but an extra effort is asked

from newcomers to the city and those belonging to what the municipality calls in its report on

integration (Municipality of Rotterdam, 2011, p. 2) the slow city2 to catch up with the

mainstream which seems to be the existing residents in the fast city. When diversity is discussed

as an asset it is seen as an economic quality. Improving social mobility of residents is often used as a

tool to generate such economic success. Policy pays little attention to social cohesion, let alone to

facilitating encounters between diverse groups. Several policy actors have expressed their

disappointment with the absence of a discussion on how to deal with diversity socially and speak

of a taboo. The findings should be understood in the light of discourse shifts on the matter of

diversity in Rotterdam and in national policies from pluralism and integrationism at the end of

the 1990s to assimilationism today.

2. Overview of political system and governance structure for diversity in

Rotterdam

2.1 The political system and governance structure for urban diversity policy

The Dutch three-tier government structure

The Netherlands is administered by three levels of government: the central government; twelve

provinces; and 408 municipalities. In addition, several municipalities form metropolitan regions.

Rotterdam is part of the province of South Holland and three urban regions in the Netherlands:

the Randstad (a conurbation of urban agglomerations), the Metropolitan region Rotterdam-The

Hague and the Urban Region Rotterdam (comprising 15 municipalities, including Rotterdam).

By mainstream policy we mean that a policy is meant to target all citizens in the city rather than a specific group.

In the policy document Doing More: Rotterdammers in Action. Integration Strategy the fast city is defined as the city of the successful

entrepreneurs, the cultural sector, the high educated, ICT, design, and the advanced harbour industry, while the slow city is the

city of poverty and stagnation, of the beneficiaries, the low educated, and the isolated population groups.

1

2

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

The central government sets out a policy framework that other government bodies abide to. It

also collects and redistributes the state budgets (Korthals Altes, 2002). Through special purpose

grants the central government can control municipal policy strategies (Ta an-Kok, 2010).

Nevertheless, the central government devolves the implementation of significant parts of its

policy agenda to municipalities. Based on the policy agenda of the central government, the

national ministries develop a policy framework for the provinces and municipalities. In the case

of Rotterdam, the provinces and metropolitan region are not significantly involved in the

governance of urban diversity. The latter is a concern of the municipality. Social policy

development, implementation and finance are increasingly being devolved to municipalities

(URBED & Van Hoek, 2008).

Government in the city of Rotterdam

In Dutch cities, and also in Rotterdam, the mayor and vice-mayors form the main executive

body. In the Netherlands, the mayor is not elected, but appointed by the government. The mayor

is chairing the council of mayor and vice-mayors, who are recruited from the parties of the ruling

coalition. This council is complemented and monitored by the city council. The mayor is

responsible for public order and safety. The vice-mayors are accountable for all other policy

matters (URBED & Van Hoek, 2009), including citizenship, citizen participation, education,

housing, urban planning, and work and income. Rotterdam is divided into 14 municipal districts.

Based on the policy agenda of ruling parties, the municipal departments set out a policy

framework for the municipal districts, which in turn gives substance to e.g. policies on urban

diversity.

It should be noted that this governance model in Rotterdam will change as of 2014. At the start

of 2013, a national government bill was passed that abolishes city districts arguing that they have

developed an undesirable level of autonomy (Eerste Kamer, n.d). In response, Rotterdam will

change its districts into area committees as of 2014. Although the latter will cover the same

geographical areas, they differ from the former in at least two significant ways. First, while the

district governments were composed of civil servants, in area committees ordinary citizens can

become members as well. Second, the coordination and implementation of policies at the district

level will be scaled up to the municipal level. While districts are responsible for the

implementation of various policies, area committees will develop policy under the guidance of the

municipal departments. The committees will develop an Area Plan that they call Doelen

Inspanningen Netwerk (Targets Efforts Network). The municipal departments will coordinate

(local) urban policy and will have the final decision-making power.

The role of non-governmental actors in the governance of Rotterdam

The municipality of Rotterdam traditionally maintains warm relationships with non-governmental

actors. At present, governing the city through public-private partnerships is the official policy

strategy of the municipality. For policies on matters of diversity, the elected city government sets out

a general policy agenda on the base of which municipal departments (as of 2014 area committees)

develop policy. During this process the departments can (but are not obliged to) consult nongovernmental stakeholders (e.g. foundations, community organisations, and researchers). The

degree to which policy is developed interactively differs for each department and policy

document. As of 2014, the area committees will be largely responsible for the implementation of

urban policy. Like the districts, the area committees will work in a network of local governmental

and non-governmental actors such as the police, schools, housing associations, and local

businesses.

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

Key actors in Dutch urban diversity policy

Relevant government actors

Diversity is not a theme that is named as such in Dutch national policy. However, it is indirectly

addressed in the policy agendas of various Ministries (see Figure 1). Before 2013, the Ministry of

Internal Affairs was the most important actor regarding migration, citizenship and diversity. It

was responsible for both the social management as well as the spatial planning for diversity. It

developed policy frameworks and funded policy programmes on integration and good

citizenship. Also, it administered the Common Integrated Approach Programme (CIAP), which aimed

to tune the integration approaches of the central government and municipalities. As for the

spatial dimension, the ministry developed policy on access to housing, and the social and

economic wellbeing of neighbourhoods. As of 2013, the social domain has shifted to the Ministry

of Social Affairs. The spatial domain remains the responsibility of Internal Affairs. Since 2010, the

national government is cutting back heavily on subsidies for organisations that represent (ethnic)

minority groups at the national level, and subsidies for integration programmes at the national

and local level (National Government Budget, 2014). A national naturalisation programme

remains, as well as subsidies for municipalities to establish facilities that counter discrimination

and encourage the emancipation of homosexuals and women.

Although Rotterdam has participated in CIAP, diversity is not mentioned frequently in its urban

policy. Diversity is indirectly addressed in the working fields of various municipal departments

(Figure 1). The Department of Social Affairs is an important actor for diversity policy and

discourses in Rotterdam. It develops and coordinates policy on citizenship and integration.

Relevant non-governmental actors

The Netherlands is home to more than 1500 migrant organisations that vary in size, age, target

groups, and activities (Van Heelsum, 2004). An important institution representing the interests of

ethnic minorities is the research and knowledge centre FORUM Institute for Multicultural Issues.

Until 2013, FORUM for instance directed CIAP together with the Ministry of Internal Affairs. At

the regional level, RADAR research, advice and knowledge institute operating against

discrimination is a key player.

Rotterdam is home to multiple organisations that represent the interests of migrants. An

influential one is the Platform Foreigners Rotterdam, an umbrella organisation for 55 migrant

self-organisations. Although, recently, the number and power of these organisations is declining

significantly due to reductions in municipal subsidies. In 2012, the Rotterdam municipality

created four knowledge centres: one with a focus on diversity, the others on emancipation of women,

the emancipation of homosexuals, and the anti-discrimination. These centres act as umbrella

organisations for the multitude of organisations on these topics in the city. The knowledge

centres collaborate with various non-governmental and governmental actors to collect and share

knowledge on these four topics.

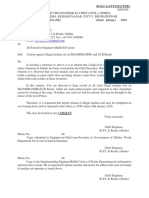

Figure 1 provides an overview of the key governmental and non-governmental actors at multiple

levels of scale and their relations in the governance of diversity in Rotterdam.

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

Figure 1. Map of key actors in the governance of diversity in Rotterdam

GOVERNMENTAL ACTORS

NON-GOVERNMENTAL ACTORS

National government

National level

Ministry of Social Affairs and

Employment:

(Integration, participation,

citizenship & ethnic minorities)

Ministry of Justice and

Security:

(Legal matters diversity &

citizenship)

Ministry of Internal Affairs:

(Housing & Neighbourhoods)

Ministry of Education, Culture

and Science:

(Education & Emancipation)

Consultancy, Knowledge and

Research Centres, Foundations, &

other advirsory organisations

Police

City

level

Municipality of

Rotterdam

City

Council

Mayor & Aldermen

Department of security

Department of Work and

Income (Social services &

economic participation)

Department of research and

business intelligence

Executive Board

Department of Social Affairs

(Citizenship, Integration,

Education, & Health Care)

Consultancy, Knowledge and

Research Centres, Foundations, and

other advirsory organisations

Department

of

Urban

Development

:

(Housing &

Neighbourhoods)

District level

Partnership for

Rotterdam

Zuid:

>

National

Programmae

Rotterdam

South

Districts / Area committees

Neighbourhood

level

Neighbourhood Network: Districts; Neighbourhood Police; Area Director; Area Manager; Special Urban Servant; Cleaning Services

LEGENDA

A

directs/funds

B

A

advises

B

A

and

B

advise

one

another

Housing Associations

Neighbourhood Network: Welfare

Organisations; Housing Associations;

Schools; Resident Organisations and

Platforms; Entrepreneurs; Other

Social Foundations and Institutions

2.2 Key

shifts

in

national

approaches

to

policy

over

migration,

citizenship

and

diversity

In the Dutch national policy context, the concept of diversity is related to matters of citizenship,

in-migration and ethnic minorities. Based on studies of Bruquetas-Callejo et al. (2011); Schinkel,

(2007; 2008); Scholten (2007; 2011); Van der Brug et al. (2009); and Vasta (2007) on the

construction and evolution of Dutch policy discourses on these themes, this chapter gives a brief

overview of key discourse shifts in national diversity and integration policy since the 1980s. To

provide a background, a brief overview is given of the Dutch post-war immigration history first.

Post-war immigration trends in the Netherlands

Just after the Second World War, the Dutch government stated that the Netherlands should not

be a country of immigration. In the 1950s, the government even stimulated emigration.

Nevertheless, between the 1960s and 2004 immigration flows have constantly exceeded

emigration flows in the Netherlands (Nicolaas & Sprangers, 2006). From the Second World War

until well into the 1990s, people from the former colonies - the Dutch-Indies, Moluccan Islands,

Surinam, Aruba, and the Antilles - migrated to the Netherlands. In the 1960s and 1970s, the

7

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

government recruited guest workers from Southern European countries and (later) Turkey and

Morocco. While the Southern Europeans mostly returned to their home countries, the Turks and

Moroccans mostly settled in the Netherlands. From the 1970s onwards, Turkish and Moroccan

migrants arrived in the context of family reunion and formation, albeit the numbers have been

declining somewhat in the last decade. Since the 1980s, the Netherlands has experienced an

inflow of refugees from e.g. Vietnam, the Horn of Africa, and the Middle East. Recently, there

has been an inflow of migrants from Western countries, including Middle- and Eastern European

countries, such as Poland, Rumania and Bulgaria.

National policy discourses on immigration and integration since the 1980s

The construction of the first Dutch integration policy in the late 1970s

Before the 1970s, the Netherlands had no policy for newcomers let alone integration policy.

Migrants were seen as transient and they were not regarded full citizens. A few guest worker policies

facilitated temporary accommodation and return services. The absence of equal rights compared

to native citizens differentiated them from society (Scholten, 2007). Various researchers including

Van der Brug et al. (2009) and Vasta (2007) understand this differentialist model of integration

through the Dutch tradition of Pillarism that entails the formation of separate group identities

Catholic and Protestant - and the emancipation within detached groups.

In the late 1970s, social tensions (e.g. reflected in riots in Rotterdam) as well as appeals of

scientists such as Han Entzinger (1975) raised awareness of the fact that immigration was not as

temporary as until then the state had thought. A report of the Scientific Council for Government

Policy (WRR) Ethnic Minorities (1979) catalysed the first integration policy in the Netherlands: the

Ethnic Minorities Policy of 1983 (Scholten, 2011). This policy called for the recognition of the

permanent stay of migrant groups and more comprehensive measures to accommodate these

groups.

Pluralism in the 1980s

The Ethnic Minorities Policy in the 1980s was pluralist in nature. Its rationale was that cultural

minority groups with a low socio-economic status should receive special attention from the state

to prevent their marginalisation. Thus, individual migrant groups such as the Surinamese, and

Moroccan were first named under the common denominator ethnic minorities (Scholten, 2007).

Ethnic minorities were granted active and passive voting rights (Bruquetas-Callejo et al., 2011).

Ethnic minorities were allowed to maintain their own cultural practices. Developing a distinctive

cultural identity was thought to stimulate socio-economic emancipation.

The Ethnic Minorities Policy initiated a wide range of policy initiatives in multiple domains,

including anti-discrimination law and voting rights for immigrants in the legal domain; policy for

housing and education, and reducing unemployment rates among migrants in the socio-economic

domain; and funding for cultural institutions to preserve migrant cultures, religions, and language

in the cultural domain (e.g. Vasta, 2007). The Ministry of Internal Affairs coordinated the policy.

At the end of the 1980s, the Ethnic Minorities Policy was heavily criticised both in public debates

and by researchers. The 1989 advisory report of the WRR played a key role in facilitating the shift

in Dutch integration policy towards socio-economic integration in the 1990s (Bruquetas-Callejo et

al., 2011). The WRR argued that under the Ethnic Minorities Policy too little progress was made

in labour market participation and educational performances of ethnic minorities. Also, a public

speech of Frits Bolkestein, leader of the Liberal Party, on the dangers of Islam for the integration

of migrants in society is thought to have played an influential role. The Dutch government held

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

on to the idea that immigration was temporary. Laws were developed to prevent further

immigration.

Integration in the 1990s and the rise of area-based policies

In 1994, the integrationist policy Contourennota Integration Policy Ethnic Minorities was launched. It was

different from the previous policy in at least three ways: it no longer focused on groups but on

individuals; it emphasised the individual civic responsibility of migrants to participate in society;

and it no longer focused on socio-cultural but on socio-economic participation (BruquetasCallejo et al., 2011). Ethnic minorities were no longer mentioned as the target of the policy. Still,

general measures, e.g. to enhance labour market participation, were hoped to reach ethnic

minorities. Under this policy framework, the Dutch Integration Law was launched in 1998. Under

this law, civic integration courses (e.g. language courses) first initiated by local governments were introduced to enhance the socio-economic compatibility of newcomers (Scholten, 2007).

In addition, in the 1990s, integration policies first took the form of area-based policies rather

than group-based policies. Precipitated by the four largest cities in the Netherlands (including

Rotterdam) a Big Cities Policy was launched in 1994 that aimed to tackle the complexity of spatial,

social and economic problems that are characteristic for many large cities. These problems

included segregation, poor housing, poverty and unemployment (Van Kempen, 2000). Next to

the Big Cities Policy various policy programmes were launched for deprived neighbourhoods in

the 1990s and 2000s, such as the Powerful Neighbourhoods (Krachtwijken) programme. These

policies share an area-based approach and integrated measures including social, economic and

physical restructuring. Accommodating and reflecting the shift from group-based to area-based

policies in the 1990s, a Minister for Urban Policy was appointed in the Ministry of Internal

Affairs in 1998. As the target neighbourhoods of area-based policy programmes often consist of

high concentrations of groups with a low socio-economic status and ethnic minority groups,

Bruquetas-Callejo et al. (2011) amongst others argue that they are essentially integration policies

as well.

A complex of events at the turn of the millennium, including a publication of a newspaper article

by Paul Scheffer (2000) on the failure of the multicultural society, the growing popularity of the

populist politician Pim Fortuyn, and several violent acts committed by migrants including the

murder of film producer Theo van Gogh, contributed to a sense policy failure with respect to

integration (Bruquetas-Callejo, 2011). In 2004, a parliamentary research committee was installed

to examine this apparent policy failure. It concluded that integration actually had been relatively

successful (Blok Committee, 2004). Policy makers found this unsatisfactory and decided to

develop stricter integration policies anyway.

Assimilation tendencies in the 2000s

The disappointment with integrationist policy evolved into the 2002 policy Integration New Style

that builds on policy in the 1990s in terms of its expectations of self-responsibility and good

citizenship of migrants. Yet, different from the previous policy, Integration New Style moves

away from mere socio-economic integration towards a focus on bridging socio-cultural distances

between migrants and mainstream society. Newcomers were expected to adjust to the

mainstream Dutch culture, reflecting an assimilation discourse. Integration has become a substitute

for being a (good) citizen (Schinkel, 2007). Also, immigration and integration policies have

become stricter. Immigration flows are actively prevented (even more than during the 1990s).

Both Scholten (2007) and Bruquetas-Callejo (2011) discuss how after the turn of the millennium

immigration and integration discourses in policy become more closely linked. For instance,

through a mathematical model Integration New Style aims to adjust the number of immigrants to

9

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

the extent in which immigrants can effectively integrate in society, both socio-economically and

socio-culturally (Scholten, 2007). For this purpose, migrant selection is justified. Furthermore,

since 2004, all migrants are obliged to pass an integration exam in order to apply for Dutch

citizenship. The integration exam is supposed to learn newcomers about socio-economic and

cultural aspects of the Dutch society. The coupling of immigration and integration discourses is

also embedded institutionally, in the change of integration policy coordination from the Ministry

of Internal Affairs to the Ministry of Justice.

According to Schinkel (2007) the recent integration policy Integration Memorandum 2007-2011 by a

new relative left-wing minister has been understood as a shift away from the focus on sociocultural assimilation to a focus on socio-economic assimilation. Still, illustrated by the slogan

Make Sure You Fit In!, the discourse of the Memorandum remains assimilationist in nature.

Active citizenship and own responsibility remain key values in the Memorandum.

Conclusions

Studies on the evolution of policy discourses on immigration and integration in the Netherlands

show a change from a pluralist paradigm in the 1980s, in which cultural differences are appraised,

towards the present assimilationist paradigm in which cultural differences are regarded

problematic. During this shift, immigration has increasingly become regulated. In Table 1, an

overview is provided by Scholten (2011) of the discussed different paradigm shifts in Dutch

immigration and integration policy, as discussed above.

Table 1. The evolution of Dutch integration policy paradigms since the late 1970s

Terminology

Social

classification

Causal stories

Normative

perspective

Guest worker policy

< 1978

Integration with

retention of identity

Pluralist policy

1978-1994

Mutual adaptation in a

multicultural society

Integrationist policy

1994-2003

Integration, Active

citizenship

Immigrant groups

defined by national

origin and framed as

temporary guests

Ethnic or cultural

minorities

characterised by socioeconomic and sociocultural problems

Social-cultural

emancipation as a

condition for socialeconomic

participation

The Netherlands as an

open, multi-cultural

society

Citizens or Foreign,

individual members of

specific minority

groups

Assimilationist

policy >2003

Adaptation,

Common

citizenship

Immigrants defined

as policy targets

because of socialcultural differences

Social-economic

participation as a

condition for socialcultural emancipation

Social-cultural

differences as

obstacle to

integration

Civic participation in a

de-facto multicultural

society

Preservation of

national identity and

social cohesion

Social-economic

participation and

retention of socialcultural identity

The Netherlands

should not be a

country of

immigration

Source: adapted from Scholten (2011)

3. Policy strategies on diversity in Rotterdam

In line with discourse shifts in national policy on citizenship, migration and diversity, Rotterdam

started with the so-called Ethnic Minorities Policy in the 1980s and the Facet Policy in the 1990s. Both

policies targeted specific groups. The latter focused on non-ethnic minority groups as well. The

focus on specific (ethnic) groups changed in the 1990s, when policies started to become more

10

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

mainstreamed. From 1998 to 2002, Rotterdam had a cross-cutting3 diversity policy called The

Multi-coloured City. The policy was based on a pluralist discourse. Diversity was defined along

socio-cultural lines and it was seen as a quality and a matter that concerns all citizens (groups) and

employers in the city. In 2001, Rotterdam openly celebrated cultural diversity as a Cultural Capital

of Europe. In 2002, this approach came to an abrupt end when after decades of rule by the

Labour Party the populist party Liveable Rotterdam (Leefbaar Rotterdam) came to power. In line

with national discourses on diversity at that time, this party aimed to achieve socio-cultural

assimilation of newcomers, particularly Muslims. Ethnic and religious differences were framed as

a safety threat for the city. So-called Islam debates organised by Liveable Rotterdam had a

polarising effect. Liveable Rotterdam gave voice to existing discontent among a significant part of

the population. Yet, by doing so, diversity was framed as a problem and a matter of ethnic and

religious divides. Since 2006, the city is governed by the Labour Party again, but they never (re)introduced the kind of diversity policies which were run prior to 20024. How does the city of

Rotterdam deal with growing diversity today?

Qualitative interviews were held with 10 governmental and 10 non-governmental policy actors on

their experiences with present policy on diversity in Rotterdam (see Appendix I). In this chapter

we first analyse governmental views on diversity policy. We examine 10 policy documents that

interviewees identified as most influential for the governance of diversity in Rotterdam (see

Appendices II and III for an overview). They fall under 7 policy areas (General Urban Policy;

Citizenship and Integration; Housing; Work and Income; Safety; Education). In addition, we

discuss how the interviewed governmental policy actors interpret the ways in which diversity is

governed in the city. Second, we discuss how the interviewed non-governmental policy actors

interpret this. The analysis of the policies and interviews is guided by eight research questions

that are outlined in Box 1. We finish with conclusions and a discussion of the findings.

Box 1. Research questions for the analysis of current policies on diversity

1. Within what legal and policy frameworks does the relevant policy act?

2. Which actors are involved in the policy development and implementation?

3. How important is diversity in comparison with other policy topics in terms of budgets

and human capital?

4. How is diversity defined, and is this a broad or narrow definition?

5. Is diversity understood as a problem, a neutral fact, or a quality?

6. Does the policy aim to foster social cohesion, social mobility, and/or economic

performance?

7. Is the policy aimed at everyone, a specific group, and/or a specific area?

8. Does the policy call for equity or the redistribution of resources; diversity or the

recognition of multiple voices; and/or places of encounter or the democratic liberalisation

of diverse groups?

By cross-cutting policy we mean that the policy applies to all municipal departments rather than to one specific one.

This short history of diversity policy in Rotterdam is e.g. based on interviews with a former vice-mayor on Diversity Policy in

Rotterdam; a municipal Programme Manager; a Policy Advisor at the RKCD; and an analysis of the Multi-Coloured City Policy.

3

4

11

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

3.1 Dominant governmental discourses of urban policy and diversity

Key policy documents

Rotterdam City Policy

At the start of their 4-year government term in 2010, the ruling coalition developed a City Plan

and an associated Implementation Strategy that respectively define what should be done and

how. All policies that we will discuss here have been developed in line with the Rotterdam City

Plan (CP) and Implementation Strategy (IS) 2010-2014.

12

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

City Plan and Implementation Strategy 2010-2014

While social cohesion and safety were central themes in previous City Plans, the main objective of

this coalition is to strengthen the economic performance of Rotterdam. It intends to do so by

encouraging talent development and entrepreneurship; creating an attractive, beautiful and safe

city to live and work; and restructuring the municipal organisation. In the Netherlands, municipal

responsibilities are increasing due to decentralisation processes while their budgets are declining.

The total budget for the municipality of Rotterdam has decreased from 4.4 billion in 2010 to

3.8 billion in 2014. Thus, the City Plan argues: we will have to do more with less [money] (p.7). Most

Rotterdammers will have to rely on their own talents; their abilities and social networks, so the

Implementation Strategy says. The coalition will continue to support the utmost disadvantaged

groups. In return, the coalition will encourage, and, when necessary, force all Rotterdammers to

participate in the economy, paid or unpaid. Newcomers are asked to make extra efforts to

participate in society. In addition, the municipality will cut back on its workforce, and ask

professional and voluntary social partners (e.g. schools, health care institutions, and volunteers)

for financial support, particularly regarding executive activities on (migrant) integration,

participation and citizenship.

The City Strategy and Implementation Strategy both refer to diversity in relation to the intended

diversification of the housing stock and business districts. Diversity is approached broadly, in

terms of age, household composition, ethnic background and lifestyle. Both policies do not

discuss how policy goals will deal with a diverse population. They merely refer to diversity as an

economic asset: We will define the economic power of our city through the diversity of our population (IS, p.4).

Note that it is not explained how policy is going to achieve this and that this is one of two

sentences in both documents that mention diversity. Social mobility and social cohesion are framed as

tools to enhance the citys economic performance in times of a declining municipality as reflected in

the following phrases: Rotterdammers develop their talents [] and hereby help the city make progress. []

Less welfare state means more welfare society5: citizens rely more on one another (IS, p.4).

The City Plan and Implementation Strategy mention a wide variety of specific target groups for

particular policy programmes and initiatives (e.g. people on benefits; elderly; students; families;

drug addicts; women). At the same time, the coalition says it wants to invest in all Rotterdammers

to support not only the economic success of the middle and upper class, but also the success of

lower socio-economic groups. The policy is implemented through an area-based policy approach

in which the wishes and needs in areas are regarded essential. The area-based approach entails an intensive and

productive collaboration with the Districts (CP, p.5). The policies strive to redistribute financial resources,

but do not solely focus on lower-income groups. It is recognised that not all Rotterdammers have

the abilities to participate equally in society. Therefore, the municipality will take care of the

utmost disadvantaged groups as national legislation requires them to do. Yet, the coalition wants

to invest in higher-income groups and successful businesses as well. The policies do not address

the social value of difference, or the right to be different, nor do they aim to generate spaces of

encounter or social cohesion. Economic performance seems to be the major drive.

Citizenship and integration policies

The most specific reference to the governance of diversity in Rotterdam was found in the

following two policy documents that address citizenship and integration. The Citizenship Policy

was referred to most often by most interviewees.

Citizens rely more on one another when the state provides less welfare services. The coalition calls this a welfare society.

13

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

Citizenship Policy. Participation: Selecting Talent

In line with the current City Plan, the main objective of this policy is to stimulate citizens to

participate in the urban economy (paid or unpaid). The policy seeks to enhance the abilities and

opportunities of all Rotterdam citizens, self-reliant and less self-reliant, by stimulating them to

develop their talents, and by reducing barriers to empowerment. The focus is on four fields of

interest: the emancipation of women, gays and lesbians; counteracting discrimination; advocating

diversity as an asset; and improving social competence and language skills through non-formal

education. The second focus area (counteracting discrimination) is subject to the Municipal AntiDiscrimination Facilities Law that obliges municipalities to provide accessible facilities to report and

get support in case of discrimination. The other focus areas are not covered by national law.

The policy follows up on the Participation and Citizenship 2007-2010 policy, is funded from the

citys budget for participation, and has suffered large budget cuts: from an annual 8 million in

2010 to 3.7 million in 2014. Funding is only available for activities that seek to share and

generate knowledge on the four fields of interest mentioned above. The policy identifies three

functions: knowledge development and sharing; volunteers get active; and the citizen in the lift. Four

knowledge centres on the emancipation of women, the emancipation of homosexuals, antidiscrimination and diversity are funded to ensure that existing knowledge on these topics is

safeguarded. Volunteer organisations and citizens can apply for funding for activities in the four

focus areas if the activities ensure social mobility and are accessible to all. The municipality asks

professional institutions for social services to take responsibility for carrying out citizenship

activities. The policy is developed in association with the four knowledge centres.

The policy uses a comprehensive definition of diversity: [] there is a wide variety of values, attitudes,

culture, beliefs, ethnic backgrounds, sexual orientations, knowledge, skills, and life experiences among

Rotterdammers (p.8). Although a key goal of the policy is to generate a more positive

understanding of diversity among citizens, it is acknowledged that diversity sometimes causes

tensions. Also, the measures that the policy suggests to develop focus on tackling negative

understandings of diversity (e.g. discrimination) rather than on extending positive developments.

The policy outcomes seek to achieve the social mobility of individual citizens in order to improve

the economic performance of (neighbourhoods in) the city. The policy wants to use the diversity

optimally to create new ideas, insights and spaces to mobilise the talents of Rotterdammers maximally (p.8). Also

references to social bonding are framed as a token for creating social mobility and economic

performance: it is important that citizens do not only develop their own talents but that through interactions

they can elicit the talents of other citizens and learn to use all existing talents in the city (p.8). The policy

explicitly states to focus on all citizens of Rotterdam and can thus be classified as mainstream

policy. The policy explicitly calls for equal opportunities for all citizens regardless of their

background (e.g. it promotes emancipation and more positive attitudes towards homosexuality6),

for the city-wide recognition of the diversity of the population, and for spaces of encounter

between people with different backgrounds (e.g. through dialogues and work-collaborations).

Specific policies to create spaces of encounter between different population groups are Opzoomer7

Mee and the programme City Initiatives. Opzoomer Mee is focused at stimulating social cohesion by

supporting joint activities in the street. Yearly, almost 1900 streets in Rotterdam participate in this

project. Through municipal grants, City Initiatives enables citizens in Rotterdam to organise city6 In 2013 and 2014 100,000 is spent on more positive attitudes towards homosexuals (half of which is specifically targeted for

acceptance amongst ethnic minority groups). 83,000 is spent on the emancipation of women. In both cases, the funds are

derived from the national government.

7 The term Opzoomeren originates from the Opzoomerstreet in Rotterdam, where in 1989 residents started an initiative to tidy

up their street. It is has become an official verb in the Dutch language.

14

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

wide activities that aim at encouraging social cohesion between residents in Rotterdam. The

yearly budgets for Opzoomer Mee and City Initiatives are 933,000 and 250,000, respectively.

Doing More: Rotterdammers in Action. Integration Strategy

In 2009, the Dutch Minister of Integration, Van der Laan, published a policy letter in which he

pleaded for a two-way integration process between newcomers and native Dutch residents, where

newcomers were asked to make an extra effort, to adapt to Dutch society. The cross-cutting

integration programme that we examine here was developed as a response to the request to the

city board to translate the letter in the context of Rotterdam. With a fairly limited budget of

approximately 150,000 of the citys budget for participation for four years, ending in 2014, the

programme facilitates dialogues and activities on integration, social tensions, culture and language

barriers between Rotterdammers with diverse backgrounds; to contribute to common visions on

Rotterdam society; and to support new networks (e.g. between the cities of Amsterdam and

Rotterdam on integration). It aims to do so in neighbourhoods as well as city-wide. The

programme seeks to support existing activities and measures in the City Plan that contribute to

integration. The content of the programme is partly influenced by the outcomes of consultation

rounds with a variety of stakeholders (e.g. researchers, citizen organisations, and governmental

actors). Although these stakeholders advised the municipality to move beyond the integration debates

(p.3), like the City Plan, the programme shares minister Van der Laans view that newcomers

should assimilate culturally and economically into Dutch Society.

The policy defines diversity relatively narrowly, along two dimensions. First, there is a big diversity

of background and lifestyles of population groups (p.2), which is mainly attributed to the continuing

process of immigration. Second, the programme speaks of the fast and the slow city [] [defined

respectively as] the successful entrepreneurs, the cultural sector, the high educated, ICT, design, the advanced

harbour industry [] [and] the city of the beneficiaries, the low educated, the isolated population groups, of poverty

and stagnation (p.2), first defined as such by Henk Oosterling, urban philosopher and

Rotterdammer. The programme argues that more attention should be paid to commonalities

between people to promote more positive experiences of diversity. Therefore, it proposes

measures that foster more positive understandings of diversity. Yet, the programme mostly

emphasises negative experiences of diversity as it concludes that overall we can speak of a heavy

pressure on social structures in Rotterdam. In line with the City Plan, the programme aims to stimulate

talent and entrepreneurship, the social mobility of citizens, so as to strengthen the economy of

Rotterdam. For instance, the programme advises to facilitate work tours in which unemployed

people of the slow city can meet employers of the fast city in the harbour. The programme claims

to be mainstream, aimed at all Rotterdammers. Newcomers to a city experience difficulties on a

number of matters including language barriers and knowledge of local institutional arrangements.

Nevertheless, according to Doing More newcomers need not expect to be treated differently from

existing residents as this would favour them above existing citizens:

We want equal opportunities for all Rotterdammers and we will counteract unbalanced

approaches. We think this is also part of the constitutional law. The constitutional law forms

a framework for the integration of new Rotterdammers. It creates order in society, entails

rules, and offers protection and opportunities to all citizens (p.4).

This phrase reflects the assimilationist ideas of citizenship that seem to underlie the programme.

The Integration Programme calls for spaces of encounter between diverse social groups. For

instance, it seeks to encourage discussion about social tensions, different cultures, and language

barriers; encourage the development of common images or consensus on Rotterdam society; and

foster new coalitions between diverse groups. The policy calls for equal treatment of Rotterdam

15

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

citizens under the law, but does not encourage socio-economic equity through the redistribution

of resources. The policy recognises a certain degree of diversity in terms of ethnicity and socioeconomic features. Yet, by arguing that citizens belonging to the slow city and newcomers should

adapt to the fast city and cultures of existing residents, it can be questioned if the programme is

really that open to diversity as it proclaims.

Housing Policy and the Rotterdam Law

The City Plan and Urban Vision 20308 form a framework for housing policy in Rotterdam. In the

Housing Vision (HV) 2007-2010 and Implementation Programme (IP) 2010-2014 this is

elaborated in more detail. In addition, several areas in Rotterdam are subject to the controversial

national Law Exceptional Measures Metropolitan Problems - popularly known as the Rotterdam Law

since 2005.

Updated Housing Vision 2007-2010 and Implementation Programme 2010-2014

In line with the City Plan and Urban Vision 2030, the current housing policy aims to make

Rotterdam an attractive residential city where people can choose from a diverse and a high quality

housing stock as part of their housing career. The Implementation Programme identifies seven

efforts to achieve these goals: improve the quality of the housing stock and living environments;

enhance residential satisfaction; encourage renters to buy; govern access to affordable housing;

raise awareness of housing opportunities and create a positive image of Rotterdam as a residential

city; and tackle and prevent nuisance. Hereby, the policy hopes to tackle selective migration9,

poor housing quality, and insufficient housing supply for low-income groups. The policy was

developed by the municipality after consultation with a number of stakeholders including housing

corporations, market parties, and residents (organisations). The municipality hoped to cooperate

with a wide variety of parties to realise their goals.

In the examined housing policies diversity is a matter of residential characteristics and

preferences. Diversity is approached comprehensively: the policies refer to socio-cultural

background, income, age, household size and type, stage in the housing career, and lifestyle of

residents. The connotation of diversity in the policies depends on the scale and the subject. At the

city level, diversity is framed as strength: housing differentiation is realised in order to

accommodate more diverse income groups, lifestyles, age groups, and household types. Also

income diversity is regarded an asset. Particularly in low-income areas, the policy strives for a mix of

incomes. This is most evident in the 2005 Act on Exceptional Measures Concerning Inner-City Problems

that is developed to regulate the proportion of low-income households in deprived urban areas10.

It is now popularly called the Rotterdam Act as it was first proposed by the municipality of

Rotterdam, arguing that certain deprived areas in Rotterdam could not accommodate any more

vulnerable residents. It is presently in effect in five designated areas in Rotterdam. Six major

housing associations in Rotterdam have committed themselves to the Act. Several scholars and

politicians in the Netherlands are critical of the Act and argue that it violates the freedom of

establishment (of vulnerable groups) (see Van Eijk, 2013a; 2013b; Ouwehand, 2006). In addition,

they believe that the Act unofficially aims at limiting the housing opportunities of disadvantaged

ethnic minorities like the proposal for the Act by the 2002-2006 Rotterdam municipality initially

claimed (Ouwehand & Doff, 2013). As this violates the constitution, the target group was then

The City Vision 2030 is a long-term spatial development strategy for Rotterdam that was developed in 2007.

'Selective migration' refers to the situation that more households with relatively high incomes leave Rotterdam than settle in the

city.

10 The Act allows municipalities to exclude people who depend on social security (apart from social security for the elderly) and

cannot financially support themselves, and who have not lived in the municipal region in the preceding six years, from rental

housing in a number of designated areas with high concentrations of low-income households.

8

9

16

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

changed into disadvantaged newcomers. Also, critics point to evaluations of the Act that show

failing results. Nevertheless, in 2013 the Act was expanded and extended for another four years.

While the Implementation Programme is positive about income diversity in neighbourhoods, it is

not so positive about diversity of lifestyles and ages: the residential and living climate is under pressure in

various places in the city due to (too) much mix of different lifestyles (IP, p.22). Therefore, the policy

advocates to use a lifestyle approach in which residential areas are labelled for a specific lifestyle

and sometimes age group (e.g. elderly; students), and house seekers are informed about this when

buying and renting housing. The lifestyle approach in Rotterdam Housing Policy is based on the

Brand Strategy Research (BSR) model by a company called SmartAgent Company. Based on

peoples' values, motives and needs SmartAgent Company identifies four categories of residential

lifestyles: yellow (involvement and harmony); green (seclusion and safety); blue (control and

ambition); and red (freedom and flexibility) (SmartAgent Company, 2008). SmartAgent Company

has categorised all neighbourhoods in Rotterdam by residential lifestyles. Housing corporations

inform renters about the dominant lifestyle in a residential area. In the case of contrasting

lifestyles renters receive a (non-binding) negative recommendation. Also future owners are

informed about the prominent lifestyle in a particular area. The lifestyle approach aims to raise

residential satisfaction by preventing social tensions. This is thought to enhance the attractiveness

of Rotterdam as a residential city. Critics question the feasibility of the lifestyle approach: can it

capture the growing diversity and change of residential preferences and behaviours and how does

it deal with conflicting lifestyles within households (Van Kempen & Pinkster, 2003)?

In line with the City Plan, the main goal in the housing policy is to enhance the economic

position of Rotterdam: it is our ambition to enhance the economic support for shops, schools and other facilities

and to generate a more balanced population (HV, p.17). Socially cohesive, high quality and mixedincome residential areas that are clustered by lifestyle act as a tool to attract higher-income groups

and achieve such an economic balance. By stimulating renters to buy, and buyers to stay in the

city, the policy seeks to control residential mobility. As such, residential mobility is a tool to

improve the attractiveness of Rotterdam as a residential city as well. Although the policies do

discuss specific housing matters for specific target groups (e.g. families, elderly, students) the

examined policy is explicitly framed as mainstream policy:

it is our ambition to improve the quality of living of all Rotterdammers. It is important that everyone,

contemporary and future residents, resides with pleasure. [] We look beyond the middle and higher income

groups that we seek to retain and attract. We pay attention to residential satisfaction of all Rotterdammers, thus

also those with a low income. Rotterdam should become a residential city for everyone (HV, p.16).

The goal to attract higher-income renters to buy a dwelling is not only presented as a way to

achieve a more balanced housing market, but also as a way to generate more affordable housing

for lower-income groups. In the Netherlands, a significant part of social housing is occupied by

middle-income groups. When they leave their rented dwelling for an owner-occupied dwelling,

more housing is thought to become available for lower-income groups. The policy does not aim

at facilitating spaces of encounter. On the contrary, by clustering residents with similar lifestyles

the policy seems to seek to accomplish the opposite. Income mix is not framed as a way to

generate contact between different social groups but as a way to increase the economic position

of the area. Notably, the policies do not explain how more socio-economically balanced

neighbourhoods will benefit the area and its citizens.

17

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

Urban Policy for Rotterdam-South

Approximately 200,000 people live in Rotterdam-South. The area is one of the most deprived

areas in the Netherlands in a form that is considered un-Dutch (NGN, 2011, p.1). Compared to

the city of Rotterdam and other cities in the Netherlands, average education levels are low,

unemployment rates are high, housing quality is poor, and residential satisfaction is low (PNP,

2013). Because of its history as a settlement place for (immigrant) dock-workers the population in

Rotterdam-South majorly consists of low-skilled workers and ethnic minorities. Due to its

relatively cheap housing stock the area is subject to selective migration11. In 2006, the

Municipality of Rotterdam, the three districts in Rotterdam-South, and four housing corporations

started a comprehensive revitalisation programme for the area called Pact op Zuid (Pact for South).

In 2012, the Programme was followed up by the National Programme Rotterdam-South (NPRS).

The NPRS consists of a Policy Programme and an Implementation Plan.

South Works! National Programme Rotterdam-South and Implementation Plan 2012-2014

The goal of the NPRS is to decrease the unnecessary deprivation among residents and to improve the quality of

life in South (PNP, 2013, p.1) so that in 20 years time the area will be on a comparable socioeconomic level with other urban areas in the G412. The programme focusses on three themes:

education, work, and housing. It aims to increase educational performance of young residents,

increase employment levels, and improve the housing stock to counteract selective migration.

The programme involves multiple forms of citizen participation. NPRS focusses on the districts

of Charlois, Feijenoord and IJsselmonde. Within these areas, most attention is given to 7 focus

areas that are considered the most problematic. The programme is coordinated by a Project

Office, and governed by the National Government, the central Municipality of Rotterdam, three

local districts, a resident committee, and various education and healthcare institutions, housing

corporations, and local businesses. The NPRS is financed by the National Government, the

Municipality of Rotterdam, and local housing corporations and businesses.

The word diversity as such is not explicitly mentioned in the NPRS. Indirectly, however, the

programme refers to it in two ways. First, it is argued that the population is young and has a mix

of backgrounds (p.8). The mixed population is portrayed as an asset as the residents are thought to

be successful in matters that governments and institutions easily overlook (p.8). Yet, these backgrounds and

matters are not defined. Second, the Programme seeks to achieve diversity of income and a

diverse housing stock. A diverse housing stock is thought to attract and retain higher-income

groups in the area. Framed in this manner, diversity is seen as a quality. Nevertheless, the

Programme does not mention how income diversity will exactly benefit the residents of

Rotterdam-South. Furthermore, generating and recognising diversity are no primary goals. The NPRS

can be classified as an area-based policy as it targets residents in designated areas in RotterdamSouth. Under all three policy themes (education, work and housing), the policy seeks to improve

the economic performance and social mobility of residents in Rotterdam-South. For instance, the policy

seeks to align local educational programmes with job opportunities, and to give benefit recipients

priority in internships and vacancies. Also, by diversifying the housing stock, the policy hopes to

give residents the opportunity for a better dwelling within their own district. The policy does not

aim to facilitate encounters between residents, let alone does it strive for social cohesion. The NPRS is

essentially a redistribution programme. The scale of socio-economic problems in Rotterdam-South

has led to the unique urban governance construction (in the Dutch context) whereby multiple

11 Selective migration refers to the fact that a relatively a higher amount of higher income groups leave Rotterdam-South than

those who settle in the in the area.

12 In Dutch Policy the G4 is used to refer to four largest cities in the Netherlands: Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, and

Utrecht.

18

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

governmental and non-governmental parties at different spatial scales collaborate with the

collective aim to improve the economic well-being of the area and its residents.

Work and income policy

At present, three policy documents on economic matters are at work in Rotterdam: the Economic

Vision 2020, the Economy and Labour Market Programme and Rotterdam Works! The first two

documents discuss diversity in relation to macro-economic processes of supply and demand (in

an implicit way). The latter addresses diversity in relation to individual people and is therefore

most relevant for this research.

Rotterdam Works! Policy Framework Work and Re-integration 2011-2014

Rotterdam Works! implements the goal of the Rotterdam City Plan 2010-2014 to encourage

Rotterdammers to participate in and contribute to society through paid or unpaid work. The goal

of the policy is:

that as many Rotterdammers who receive benefits as possible become economically

independent and no longer need benefits. Every client even if paid work is not feasible (yet)

is active by contributing to society in a meaningful way. Meanwhile, they develop themselves.

This, we call Full Engagement (p.5).

The implementation of Full Engagement is guided by six priority areas. First, in order to

encourage paid work, the policy will stimulate educative reintegration trajectories for unemployed

people through a combination of paid and unpaid work. Second, employers will have the

opportunity to receive municipal subsidies for the labour costs of employees who are in the

process of reintegrating into the labour market. Third, young people will be required to either

have a paid job or to be in education. Fourth, language education will help participation in society

through paid or unpaid work. Fifth, barriers to paid employment that are caused by health issues

will be mapped and addressed. Sixth, the municipality will form partnerships with professionals

(e.g. health insurance companies, housing corporations, healthcare facilities, schools, industries

and businesses) to improve the effectiveness of its strategies. The policy relies on the

participation of unemployed residents in Rotterdam (receiving benefits).

Diversity is not mentioned explicitly in Rotterdam Works! However, the policy does acknowledge

the existence of diversity in abilities of residents to participate in the urban economy. All

residents are required to participate and hence it is assumed that they can. Nevertheless, in the

policy residents are allowed to partake according to their capabilities. The policy assumes that all

Rotterdammers possess talents. This reflects a positive understanding of the abilities of citizens.

Citizens receiving benefits can be seen as the principal target group of the policy. The policy pays

particular attention to people that experience difficulties accessing the labour market, young

people receiving benefits, and newcomers to the city that are obliged to or want to follow

language and integration courses. However, paid work is presented as the norm. The unemployed

and the benefit recipients are presented as a problem:

Rotterdam is a working class city, and we are proud of this. Sitting on the couch at home

while being unemployed and receiving benefits is not an option (p.3).

And:

Rotterdammers that can but do not want to [participate in the economy] get sanctioned (p.12).

19

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

Rotterdam Works! can be regarded as a redistribution policy, albeit one subject to conditions and

obligations for the recipients. While the national and municipal budgets for socio-economic

participation have declined significantly (even though demands for benefits are increasing), the

policy does seek to provide disadvantaged people with tools to increase their socio-economic

opportunities. The main goal of the policy is to increase the social mobility of residents so as to

improve their economic performance and reduce their dependency on state benefits. The examined

policy does not seek to generate encounters between people with diverse backgrounds, let alone does

it seek to generate social cohesion.

Safety Policy

Programme Safety 2014-2018. #Safe 010

The Programme Safety 2014-2018 acts as a framework for all safety-related programmes and

projects. The policy aspires that all neighbourhoods in Rotterdam are safe, and that residents, entrepreneurs

and visitors of the city feel safe (p.3). A four-tier approach is adopted. First, Rotterdammers are at the

heart of the governance of safety in the city. In collaboration with the municipality and the police,

residents determine which three problems with regard to safety and liveability deserve most

priority. Second, the municipality will enforce the law and meanwhile invest in new ways to make

people live up to it. Third, the municipality wants to collaborate with multiple parties at various

scales (e.g. the national and local police, residents (platforms), city districts, local businesses) to

improve its approaches regarding safety in the city. Last, the municipality will inform all parties in

Rotterdam about safety matters in the city so as to move towards a collective approach. The

policy has been developed by the municipality in collaboration with residents, entrepreneurs,

academics and professionals.

The examined 44-page long Safety Policy refers to diversity twice. First, it does so when

discussing the intended collaborative approach. A broad definition of diversity is used:

the structure of the population is changing. There are more young people and elderly people.

Newcomers arrive. We will keep in touch with all these groups and their social networks

(p.6).

It remains unclear who 'all these groups' exactly are. Their existence is presented without a

particular positive or negative implication for the governance of safety in the city. In the second

reference to diversity, the term ethnic diversity is used. Ethnic diversity is portrayed as a potential

threat to safety that professionals will be trained to deal with. Particularly groups that are

culturally different, can form a risk for society, it is argued:

having a different cultural background can cause difficulties to participate in society. Due to

mutual misunderstandings that are caused by cultural differences, it is sometimes difficult to

reach out to these groups. Therefore, we give these groups particular attention. We make

contact with communities of diverse cultural backgrounds. [] With our knowledge, we

train professionals how they can deal with cultural diversity. [] In addition, we discuss

with these communities how they can better utilise their own powers to take responsibility

(p.31).

Neither the targeted cultural groups, nor the groups that do not form a potential threat are

defined in the Safety Policy. Perhaps, the Rotterdam Action Programme Antilleans that targets

problems of Antilleans (on display on a municipal webpage on safety policy) may serve as an

indication of this policy approach. Besides ethnic minorities, the Safety Policy in Rotterdam

targets several other so-called risk groups, such as drug criminals, radicalised people, EU-migrants,

20

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

homeless people as well as (criminal) young people that cause nuisance. The policy uses an areabased approach. It targets all neighbourhoods in Rotterdam differently. Those that are relatively

unsafe get particular attention. Amongst other initiatives, a project with so-called urban marines is

set up to improve the safety in these neighbourhoods. As most attention is paid to the most

vulnerable groups and areas the Safety policy can be regarded a redistribution policy.

The policy acknowledges that socio-economic and socio-spatial disadvantages can encourage

criminal behaviours, but does not focus primarily on encouraging social mobility or economic

performance of residents. Instead, the policy mostly focuses on correcting unlawful and

encouraging lawful behaviours. The use of role models to prevent young people and ethnic

minority groups to isolate themselves from society can serve as an example of this behaviourcentred approach. In several ways, encouraging social cohesion is used as a tool to prevent criminal

behaviours, not as a goal in itself. As an example, the policy discusses an experiment of the

municipality, the Last Chance Approach, where an appeal is done to the social networks (e.g.

family, friends, and teachers) of young people with negative behaviours [] to activate and support them

to change their behaviour and to solve their problems (p.37). Indeed, stimulating encounters between people

with legitimate and illegitimate behaviours is used as a means to encourage safety in the examined

policy.

Educational Policy

Rotterdam Educational Policy 2011-2014: Better Performance and Attack on Drop-outs

Current educational policy in Rotterdam consists of two related policy documents: Better

Performance (BP) and Attack on Drop-outs (AD). Both aim to increase the quality and performance

of education in Rotterdam. The former intends to increasing educational performances, through

three lines of approach: extending school hours; professionalising the educational environment;

and raising parental involvement in the educational career of their children. The latter aims to

prevent school drop-outs through two lines of approach: keeping children at school; and guiding

children that have dropped out back to school. The educational policy is complemented by

various projects and programmes. For this study, an interesting one is the Good, Better, Best project

under the Language Attack Programme that aims at increasing parental involvement at school by

improving the Dutch language skills of parents that have difficulties with the language. It is

financed by the EU. The Educational Policy is largely financed by the national and municipal

government. Some programmes and projects are financed by the schools themselves. The policy

was developed by Rotterdam School Boards and the Municipality and carried out by educational

employees, volunteers, parents, municipal employees, and businesses.

Diversity is not a prominent topic in current education policy in Rotterdam. Nevertheless, the

Better Performance document does refer to diversity twice. This is first implicitly, as a matter of

ethnicity and socio-economic status:

Rotterdam is home to a range of nationalities. Two third of young people grow up in families

that do not descend from the Netherlands. Although Rotterdam is home to many second and

third generations immigrants, often little or no Dutch is spoken at home. One in three

students grows up in a family with low-educated parents. These young people rarely

participate in higher education forms and do not always obtain a degree to participate in the

labour market (BP, p.13).

The second reference to diversity is more explicit. Rotterdam schoolchildren are described as very

diverse in backgrounds and language and development levels (BP, p.13). In both instances, the diversity is

framed as a problem for the socio-economic well-being of the city and for teaching the children,

21

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

respectively. The policy aims to solve these problems by stimulating disadvantaged and nonDutch speaking groups to assimilate into the (Dutch) urban economy. The Attack on Drop-outs

document does not explicitly refer to diversity, and uses general terms such as youngsters, children,

and Rotterdammers to describe its target population. Both policy documents indirectly refer to

diversity in another way: a diversity of talents. In contrast with ethnic and socio-economic

diversity, diverse talents are framed both as a quality and a challenge. Thus, the policy recognises

diversity but certainly does not promote it. Although the Educational Policy is aimed at all

schoolchildren in Rotterdam under 23 years old, specific attention is given to so-called target group

children [] [defined as] children of whom at least one parent was born in a non-Western country or of whom the

parents were born in a Western country and at least one parent has a low education level (BP, p.10) and their

parents, as well as children that perform exceptionally well at school. Priority is also given to

children that live in disadvantaged neighbourhoods13 of Rotterdam. The policy shows elements of

a redistribution policy but cannot be regarded as such completely because it invests both in

disadvantaged groups and areas and children that perform well. Increased social mobility and better

performance of school children are framed as the primary goals of the policy as this is thought to

benefit the economic performance of the city as a whole:

with its relatively young population, the city is a breeding ground for talent. It provides

opportunities but also challenges to allow this talent to develop optimally. There are still too

many youngsters who do not utilise their talents enough. In addition, a well-educated labour

force is essential for the economic, social and cultural development of the city. Education in

Rotterdam plays a key role in this (BP, p.3).

The policy does not aim at generating encounters between diverse social groups to stimulate positive

understandings of diversity. Two arrangements that are discussed in the policy do focus on

generating social cohesion: Intensive School Arrangements (ISO) for schools that perform (very) weakly

and Top Classes for all other schools in Rotterdam. As part of these programmes, schools are

linked to each other to support schools to further develop a method that leads to better educational results

(BP, p.15). However, as the phrase shows, in these arrangements social cohesion is not portrayed

as a goal but a means to accomplish the primary policy goal of better educational performance of

schools.

Interpretations of diversity policy by governmental actors

Out of the interviews carried out with 10 governmental policy actors, we have identified seven

interrelated themes concerning the extent to which and ways in which policies address diversity

in Rotterdam.

Little attention for diversity

Most governmental policy actors confirm that the word diversity as such is not often explicitly

mentioned in present policy documents in Rotterdam. Interviewees argue that diversity is also

not discussed much in municipal departments, districts, and social institutions. For instance, a

Political Advisor argues:

Years ago, I used to work with it [diversity] a lot as a civil servant. But, in recent years this

is not the case anymore. I believe that it has faded away a bit. Before, there used to be an

13 On the basis of four categories (capacities, living environment, participation and social bonding) the Municipality of Rotterdam

monitors and classifies its neighbourhoods with a Social Index (see CRRSC, 2009). Disadvantaged neighbourhoods are defined

through their low score on this index.

22

DIVERCITIES 319970

4 August 2014

entire post for Integration and Participation [policy]. Today, this [formal attention for

diversity] has certainly become less [6 January 2014].

Interviewees explain that within the municipality diversity is presently a matter of the Social

Affairs Department. Nevertheless, the interviewees argue that it should be a cross-cutting matter: