Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Puerto Rico's Economy: A Brief History of Reforms From The 1980s To Today and Policy Recommendations For The Future

Uploaded by

eriel_ramosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Puerto Rico's Economy: A Brief History of Reforms From The 1980s To Today and Policy Recommendations For The Future

Uploaded by

eriel_ramosCopyright:

Available Formats

Puerto Ricos Economy:

A brief history of reforms from the 1980s to today

and policy recommendations for the future

Recent headlines have highlighted the currently distressed economic status of Puerto Rico, however, few understand some of

the historical factors that led to its current state. After describing

some of the structural reforms over the last three decades, this

paper concludes with a brief description of the present economy,

as well as a discussion of policy alternatives.

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

Executive Summary

Despite being an island paradise, Puerto Rico is far from an economic one.

Recent headlines have highlighted Puerto Ricos struggling economy, demonstrating a need for substantial policy shifts at the local level, as well as consideration

towards improving relevant federal policies.

Few are aware, however, of the decisions that have led to Puerto Ricos

recently distressed state, nor the policies that developmental economists would recommend in order to change its projected, long-term path.

The following paper provides the historical context necessary to understand

how Puerto Rico developed from an agrarian-dominated society in the early 20th

century, to a semi-autonomous territory whose knowledge-based economy has been

granted sovereignty in some areas, while also limiting policymakers tools in others. Economic parallels to other countries who share Puerto Ricos Latin American

roots offer some insights into Puerto Ricos economy today, nonetheless, Americas

hegemony has ensured considerable distinction.

Puerto Ricos economy remains closely tied to that of the U.S., yet it is more

deeply impacted by recessionary periods and often fails to capitalize on economic

expansions. Specific incentives and federal tax policies have been enacted in an attempt to counter the effect, however, some policies have led to deeper dependence

and little growth, and in some cases, countercyclical fiscal and monetary policies

have exacerbated worsening economic conditions.

When compared to the rest of the U.S., Puerto Ricos current economy is

relatively tenuous. Total outstanding public debt has grown substantially, doubling

in the 1980s, and again in the 1990s, while tripling since 2000. Despite numerous

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

new reforms and policy shifts, as well as a recovering American economy, Puerto

Rico still has a number of economic impediments to overcome, including, but not

limited to: borrowing costs that outpace current or projected growth, high unemployment, a large informal economy, a high percentage of impoverished citizens, a

shrinking labor pool, and stagnant economic growth.

Federal policymakers have several reasons to be concerned. First, millions

of Americans have some exposure to Puerto Ricos bonds, whose fluctuations could

impact financial markets. In addition, changes to bankruptcy protections, tax laws,

and Puerto Ricos current status have implications for the rest of the U.S. Last,

since Puerto Ricans are American citizens, federal policymakers have an obligation

towards their general welfare.

Although there are many specific recommendations that can, and should,

be implemented, the report discusses several broad changes that must be made,

including:

Shift long-term and current taxes and other incentives to focus on investment

that directly encourages the hiring of Puerto Rican citizens;

Ensure that policies emphasize growth in labor intensive versus capital intensive industries;

Reduce and limit island-wide bureaucracies that impede entrepreneurial development;

Invest in the retention and development of human capital, including expanding

investments in primary through post-secondary education;

Shift from targeting hiring credits to emphasizing sectoral job training programs;

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

Adjust public assistance programs to ensure that reservation wages do not depress job creation and labor participation;

Make a quick and permanent status decision (i.e. whether to remain a territory,

become a state, or gain independence) that will again give confidence to future

generations of Puerto Rican citizens, as well as potential long-term investors.

Although many of the specifics of such recommendations have to be deter-

mined by local administrators, these broad categories of reforms should serve as a

framework within which policymakers across the country can work to ensure that

Puerto Rico does not continue to rely upon policies that have little positive impact

on, or are in fact detrimental to, Puerto Ricos economy.

Introduction

Puerto Ricos economic and social history began very similarly to that of

many other countries traditionally considered Latin American. Yet, despite being

among the first discoveries of Spanish explorers, Puerto Ricos economic similarities diverged when it became a colony of the United States, instigating an argument

among economists and other social scientists as to Puerto Ricos designation as

such. As a semi-autonomous American territory today, Puerto Ricos economic

trajectory has been largely impacted by external policies enacted by U.S. legislators, ensuring that its economy has closer ties to the U.S. economic system than

others in the Western Hemisphere. Nonetheless, this paper will analyze Puerto

Ricos economic development considering Puerto Ricos historical ties to Latin

America, as well as its relatively more recent one to the U.S. - by first providing the

historical basis for its current economy, then discussing the reforms that have been

implemented in recent decades, while considering the impacts that reform policies

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

have had on economic growth, poverty, and income inequality. Finally, it will provide an analysis of recent and current policies and their effectiveness in promoting

economic development.

Brief History

Puerto Rico was founded by Spanish expeditions in 1493, subsequently be-

coming a colony of the Spanish crown for more than 400 years. When the United

States defeated Spain in the Spanish-American War, it acquired a number of territories, including Puerto Rico. The U.S. introduced a government that was subject

to federal law, but given a range of latitude and autonomy in setting local policies.

After a series of Supreme Court cases, known as the Insular Cases, Puerto Rico

was officially deemed an unincorporated territory that would not be subject to the

revenue clauses of the Constitution, despite maintaining a number of fundamental

rights (Gerow, 2014). Puerto Ricans were granted U.S. citizenship in 1917 and

the territory officially became a Commonwealth under its constitution in 1952, a

status that it maintains today.

Economy

Although offered some autonomy, Puerto Rico has never had full authority

over its own economy and government. The Jones Act of 1917 granted Puerto

Rico authority over its own local tax policy, yet, in 1920 the Merchant Marine Act

ensured that ships had to first go through U.S. ports before heading to Puerto Rico,

inflating the costs of goods brought to the island. Puerto Rico is also required to

maintain the federal minimum wage, and has to apply the same labor and environmental standards as the rest of the U.S., while not being allowed to negotiate

bilateral trade agreements and having to adhere to fiscal policy directed by the U.S.

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

Congress and monetary policy controlled by the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Despite these economic impediments or perhaps because of them the

U.S. enacted a series of polices that allowed Puerto Rico to use its tax autonomy to

its own advantage. Section 931 of the Revenue Act of 1921 (originally section 262)

sought to boost economic growth by providing corporate tax exemptions for all

U.S. corporations with income derived in Puerto Rico, while Puerto Rico doubled

down with its own local income and other tax incentives. As a result, combined

with a less expensive labor force and the advantages of being a U.S. territory, labor

intensive manufacturing grew dramatically in Puerto Rico. Between 1950 and the

mid-1970s, output per employee grew by nearly 5 percent per year, a rate comparable to the well-known, dramatic growth of East Asia (Collins, et al., 2006). In

1950, GDP per worker was about 30 percent of the U.S. average, while in 1980 it

peaked at todays level of approximately 74 percent, making Puerto Rico one of the

worlds most developed Latin societies (Griffin, et al., 2011). Despite macroeconomic growth, labor force participation has remained below 50 percent since 1960,

while the U.S. rate has climbed to above 60 percent. Gross National Income (GNI)

has also declined as a fraction of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) during this time

period, meaning that more foreign entities and individuals were transferring their

economic output to locations outside of Puerto Rico.

Tax incentives under Section 931 contributed to a decrease in federal tax

revenues while leading to little growth in employment in Puerto Rico, compelling

the U.S. Congress, in 1976, to replace the tax exemption policy in favor of one

that allowed domestic tax credits for foreign taxes paid. The new Section 936 still

allowed for favorable tax treatment and, in fact, contributed to the vast growth of

wholly-owned subsidiaries in Puerto Rico, but instead shifted the incentive from la-

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

bor intensive industries to manufacturers in capital intensive industries. The resulting lack of employment growth attributed to the increase in Congressional scrutiny

over the next two decades regarding the continued benefit of Section 936 to Puerto

Rico (Gerow, 2014).

Puerto Rico has transformed from an agriculturally-based economy to one

based on industrial manufacturing, to a knowledge-based economy today, yet its

economy is still directly tied to that of the U.S. and is more greatly impacted by

contractionary periods in the American business cycle than the mainland itself.

During the U.S. recessions in the 1970s and 1980s, Puerto Rico suffered from economic contractions that were longer than in the rest of the country, which were

sometimes exacerbated by policy changes related to its tax incentives. While making some economic gains during the U.S. boom of the 1990s, since the start of

the new millennium Puerto Rico again suffered through nearly a decade-long contraction, while becoming heavily dependent on transfer payments and other public

assistance from the U.S. Federal Government. Federal transfer payments equaled

27 percent of GDP in 2010, while more than half receive some type of government

assistance today (Vlez, 2011).

Todays economy has been widely criticized as being on the brink of economic collapse (El Nuevo Da, 2015; Caribbean Business, 2015; Vlez-Hagan,

2013; Greece, 2013; Green, 2013). Puerto Rico has had a budget deficit for more

than a decade, which has contributed to a growing public debt which, in total, has

surpassed more than 100 percent of GNP (total economic output by Puerto Rican

citizens within its borders), while some estimate it to be much higher (Government

Development Bank, 2015; El Nuevo Da, 2015; Colegio CPA, 2014). Unemployment is also rampant, stagnating at around 14 percent (not including the large in-

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

formal sector, which is estimated to comprise nearly 40 percent of the economy),

while labor force participation remains low at nearly 40 percent (U.S. Department

of Labor, 2015). Puerto Ricos economy has been contracting for nearly a decade,

while analysts see little opportunity for growth, which has resulted in credit downgrades from all of the major rating agencies leaving few opportunities for additional borrowing required to finance government operations (Colegio CPA, 2015;

Government Development Bank, 2015; Kuriloff, 2015).

The following section will provide an overview of some of the structural

reforms that have been enacted between the late 1970s and today, and will continue

with a short description of the reforms that the government has considered recently

or is considering enacting today.

Economic Structural Adjustments

Although Puerto Rico did not undergo the same structural adjustments

that other Latin American countries were required to undertake (per IMF and World

Bank lending requirements) following their economic crises (Franko, 2007), it has

implemented a number of structural reforms, many at the direction of the U.S. Federal Government, that have had varying repercussions. It should also be noted that,

unlike in independent countries, Puerto Rico is limited to reforming only its local

fiscal policy, leaving monetary and major fiscal policy to the discretion of the U.S.

Federal Government.

Reforms in the 1980s

After Congress replaced Puerto Ricos corporate tax incentive scheme with

the new Section 936 tax credit law in 1976 and American corporations began

establishing wholly-owned subsidiaries in Puerto Rico to take advantage of the

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

new incentives Puerto Rico enacted its own Industrial Incentive Act of 1978,

which lowered the effective tax rate on corporations even further. However, after

Congress closed several previously advantageous loopholes, corporations began a

notable shift in manufacturing. Whereas, previously it was more beneficial to bring

labor intensive manufacturing to the island, the new law incentivized corporations

to shift intangible property to Puerto Rico, leaving large investments in R&D behind to take advantage of lucrative tax credits on the mainland (Weisskoff, 1985).

Instead, products would only be finished in Puerto Rico to apply tax breaks that

applied only to completed products, which significantly reduced the number of

employees required in the manufacturing process. Pharmaceutical companies were

among the most adept at implementing these tax policies, as more than 80 percent

of the most prescribed drugs in the U.S. were manufactured in Puerto Rico by 1990

(GAO, 1992).

The Federal Government also greatly improved the amount and efficiency of

transfer payments and other public assistance to Puerto Rico during the late 1970s

and 1980s. For the first time, Puerto Ricans became eligible for the Food Stamp

program in the 1970s, while other public assistance doubled during the 1980s as

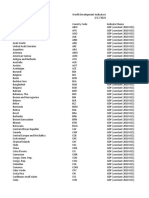

shown in Table 1 of the Appendix (Segarra, 2006).

Puerto Ricos own legislators also made a significant number of reforms

during this time period. Government investment increased substantially in programs

to promote economic development. The Government Development Bank was officially created, while it also began investing in programs to facilitate regional exports

produced by local businesses. Because of the substantial investments, deficit spending increased considerably during the 1980s, doubling outstanding public debt from

approximately $6 billion to more than $12 billion by 1990 (Vlez, 2011).

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

Reforms in the 1990s

During the 1990s, economic growth both in the mainland U.S. and in Puerto

Rico was positive, however, Puerto Ricos economy was met with another series of

reforms that had lasting economic impacts. After extensive welfare reforms were

passed in the U.S. in 1996, Puerto Rico too incurred reductions in the transfer payments that supported nearly one-third of the economy. In the same year, Congress

also decided to abolish Section 936, which Puerto Ricos manufacturing and pharmaceutical industries relied upon, citing a lack of meaningful employment gains for

Puerto Rico as well as revenue concerns at the U.S. Treasury (Gerow, 2014).

Although Congress allowed for a ten year phase-out of Section 936, manu-

facturing immediately declined; less than one-third of those previously taking advantage of the law accounted for total manufacturing employment. To counter the

effects, Puerto Rico attempted to shift the economy to greater emphasize tourism

and the service sector, yet 40 percent of GNP remained dependent upon the manufacturing sector (Vlez, 2011).

Various other public works initiatives and investments were developed

during this period as well. Administrators funded public works projects that created an urban train system, a new super-aqueduct water system, the Coliseum of

Puerto Rico, and a new convention center (Ayala & Bernabe, 2007).

The government also began privatizing some government-owned entities in

the 1990s. As government agencies and public corporations were consolidated and

privatized, healthcare reform ushered in a new privately-run healthcare system, and

public employment was subsequently reduced.

As a result of the public spending initiatives, total public debt again doubled

10

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

between 1990 and 2000, from nearly $12 billion to $24 billion (Government Development Bank, 2015).

Reforms in the 2000s

Bookended by two recessions, one in 2001 and another beginning in 2006,

the decade of the 2000s has been especially harmful to the economy of Puerto Rico.

Due to these periods of contraction, the government of Puerto Rico took especially

severe measures to stymie the economic and social impact.

Public investment again led to major deficits and growing long-term debt.

After investing more than $1 billion in self-managed community projects to decrease poverty, the government also increased spending on infrastructure projects

and created other new programs to reduce poverty and government dependence, all

of which helped to increase public employment by nearly 12 percent in just the first

half of the decade (Vlez, 2011).

While implementing a new consumption tax to increase public revenues

and fiscal stability, Puerto Rico simultaneously lobbied the Federal Government to

help salvage its manufacturing-dominated economy. With Section 936 officially

ending in 2006, Puerto Rico has ensured that some tax deferral policies still remain

(Gerow, 2014). However, the shifting tax code continued to lead to greater consolidation within the manufacturing industry and a shift to more capital intensive

investments, further reducing the need for employees in this sector.

Despite an inability to form bilateral trade agreements, Puerto Rico contin-

ued to work with the Federal Government to establish its role and ensure lasting

benefits from certain trade agreements, as well as its relationship with other countries in the Hemisphere. Puerto Rico again sought to reestablish and build new

11

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

agreements with both CEPAL and CARICOM, among others, hoping to boost trade

and export opportunities for its local businesses (Ayala & Bernabe, 2007).

Nonetheless, after the phase-out of Section 936 was completed in 2006,

combined with the U.S. Banking Crisis and a large and growing deficit and public

debt, the economy was pushed into one of the worst recessions on record, prompting even more drastic measures to be enacted. Public employees salaries were

frozen and 28 public agencies were consolidated (which resulted in a two-month

government shutdown and an estimated economic impact of more than $2 billion),

major utility subsidies were eliminated, taxes were increased on the banking sector,

and an island-wide sales and use tax was created (Harvard Law Review, 2015).

In 2009, Puerto Rico welcomed a new governor and administration, hoping

it would counter the ever-increasing $3.3 billion deficit, which equaled nearly onethird of the islands total annual revenues (Government Development Bank, 2015).

The governments liquidity problems required that the Governor had to immediately take out a loan to cover the first public payroll under his new administration

(Casey, 2012). The following several years heralded a drastic structural adjustment

period. More than 20,000 public employees were laid off, government spending

was reduced by 10 percent, taxes were raised in some sectors and on high-end real

estate and earners, contract negotiations and pay raises were frozen, corporate tax

rates were flattened and reduced, toll roads and the islands biggest international

airport were privatized, and more than $4 billion was borrowed to cover government liquidity needs (Vlez, 2011). The government also enacted two major laws

intended to boost foreign investment by reducing, almost to zero, income taxes on

returns in real estate and passive income (Government Development Bank, 2015).

12

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

At the same time, government transfer payments were again increased sub-

sequent to the passage of the Affordable Care Act, which also allowed for increased

investments in a number of public assistance programs (Public Law, 2010).

Reforms Today

Since 2013, a newly-elected administration brought about a major shift in

economic policy. Deficits and employment remain major issues, while a mass exodus of professionals to the mainland U.S. continues to reduce the number of contributors to Puerto Ricos economic output as well as to government revenues (total

population decreased by 4.7 percent from 2010 to 2014) (Abel & Dietz, 2014). In

order to counter the deficit, major tax provisions from the previous administration

were overturned, effectively increasing taxes by as much as 60 percent on high-income, domestic earners, while funding for schools and other social investments

have been reduced, public employee salaries were again frozen, public employee pension reform was passed to privatize pensions, major reorganizing initiatives

were enacted on some of the more inefficient utilities, and even more incentives are

being offered to instigate foreign direct investment (Slavin, 2014).

Knowing that the current levels of debt will continue to inhibit Puerto Ricos

ability to return to economic growth, the current administration has attempted to restructure some of its existing liabilities. Courts, both in Puerto Rico and in the U.S.

mainland, have overturned several attempts to do so (Harvard Law Review, 2015),

yet, Puerto Rico has also begun to lobby Congress to allow the territory to restructure its debts under Chapter 9 of the Bankruptcy Code, an option currently unavailable to the islands government. In order to find alternative means for increasing

revenues to cover debt service as well as continuing government operations, the

island has recently passed a tax on crude oil, while now debating a value-added tax

similar to that of many European countries. Contrarily, Washington, D.C. is now

13

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

considering overturning an IRS tax law that allows foreign corporations to deduct

corporate taxes that it pays to Puerto Ricos government, which Puerto Rico has

recently used to help boost corporate tax revenues without decreasing the incentive

for corporations to locate within its borders.

Much like in other parts of Latin America, reforms in Puerto Rico have had

substantial, if not always immediately evident, effects on the economy, which will

be discussed in the following section.

Growth, Income Inequality, and Poverty

1980s

During the late 1970s, annual GDP growth improved significantly, reaching

a peak of 5.4 percent in 1979, while unemployment fell from a high of 20 percent

in the mid-1970s to 16 percent in 1980 (U.S. Department of Labor, 2014). High

growth continued through the end of the 1980s, while public debt also increased

dramatically (Vlez, 2011). The boom in manufacturing from Section 936 is often

attributed to improvements, however major investments in works projects as well

as business incentives can also be attributed (Collins, et al., 2006).

While nearly two-thirds of all households were under the official poverty

line in 1969, poverty declined in both the 1970s and 1980s, most significantly reduced among the most impoverished (Sotomayor, 1996). After the Food Stamp

program and other major increases in transfer payments were extended to Puerto Rico, income among the poor increased dramatically in the 1970s and public

assistance income doubled in the 1980s (Table 1, Appendix). Rising wages and

household incomes increased income inequality over these two decades, however

transfer payments negated this effect, leading to reduced inequality and a lower

Gini coefficient (Table 2, Appendix).

14

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

1990s

The increasing importance of the Internet in commerce, along with new free

trade agreements in the 1990s, led to greater globalization and competitiveness for

Puerto Ricos manufacturing and export sectors; its competitive advantage was further reduced after the repeal of Section 936 tax incentives. Yet, substantial growth

still continued throughout all of the 1990s, with GDP growth averaging above 3

percent, annually. Employment also greatly improved. After reaching a high of

more than 16 percent unemployment, by the end of the decade Puerto Ricos unemployment stood at around 10 percent (U.S. Department of Labor, 2015).

As demonstrated in Table 1 of the Appendix, a major shift in public assis-

tance benefits occurred in the 1990s as they began to comprise a lower percentage

of total income (Segarra, 2006). Tables 2 and 3 reveal how a simultaneous increase

occurred in the Gini coefficient of more than 11 percent, demonstrating a marked

increase in inequality during a generally successful period of economic growth, a

common occurrence in developing economies.

2000s

Some economists have come to call the 2000s Puerto Ricos lost decade.

Growth since 2000 has been effectively zero, while contracting during the Great

Recession through today. The recession of 2001 exacerbated the flight of manufacturers that resulted from the repeal of Section 936 in 1996, leading to a subsequent

decrease in manufacturing employment of nearly 10 percent, with a total drop in

manufacturing employment greater than 34 percent through 2010 (Government

Development Bank, 2015), losses that continue through today. After reaching new

lows of approximately 10 percent, the official unemployment rate again increased

after the recessions, reaching as high as 16.9 percent in 2010 and remains near

15

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

14 percent today (U.S. Department of Labor, 2015), while combined with a large

informal economic sector (some estimate to be nearly 40 percent of GDP) many

estimate real unemployment to be much higher. Some economists have concluded

that the repeal of Section 936 decreased GDP growth by as much as 5 percent after

the recession of 2001, continuing through today (GAO, 2006), although many point

to multiple other factors that have attributed to the depressing the economy.

During the last decade, the Gini coefficient officially declined from .56 to

.53, despite the impact of two recessions that had an even greater negative impact

on Puerto Ricos economy than that of the rest of the U.S. (Census, 2010). Some

have suggested that this can be attributed to the emigration of professional and

high income earners that have disproportionately left Puerto Rico since the mid2000s (Abel & Dietz, 2014), while others point to accounting and inflation adjustment considerations in both the Gini Index and official poverty statistics (Guerrero,

2004).

Given the number of varying reforms with even more disparate impacts

that Puerto Rico has implemented over the last several decades, there are numerous

analytical opinions and suggestions for future economic growth that can be drawn

upon.

Analysis and Opinion

Tax Policy

Although it initially contributed to the substantial development and growth

of the manufacturing sector in Puerto Rico, federal tax policy should not be relied

upon as a major driver for long-term economic growth. Numerous analyses and

studies have shown that federal tax policies that were created with the intention

16

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

of boosting employment in Puerto Rico have fallen far short of their goal (Gerow,

2014), by instead bringing capital intensive industries to Puerto Rico which have

little impact on job creation. By adding its own incentives, Puerto Rico is helping

to subsidize many of these large corporations, which is creating a missed opportunity to obtain revenues for investment in the development of other industries.

Instead, Congress, and the Puerto Rican government, should invoke policies which

tie investment in Puerto Rico directly to the hiring of Puerto Ricans.

Local tax policy, as well as a comparatively bureaucratic entrepreneurial

environment, is also adding to the lack of development on the island. Recent initiatives have substantially increased income taxes on businesses developed domestically, which has reduced the incentive for native Puerto Ricans to develop businesses and has perpetuated the exodus of Puerto Rican entrepreneurs and business

owners to the mainland.

Industry Diversification

The lack of diversification in economic development has contributed to finan-

cial crises throughout Latin America. Due to both U.S. Federal Government and local tax incentives, Puerto Rico became dependent on the manufacturing sector, which

has become highly concentrated over the years. Puerto Rico should invest in the

growth of sectors that traditionally have higher rates of employment and can employ

the existing workforce, including and especially the service sector. Analysts consider service, especially in the tourism industry, to be underdeveloped, leaving a vast

opportunity for growth, job creation, and long-term positive economic development.

Recent incentives have been enacted with some success, however, they are again creating an opportunity for low levels of diversification and shallow employment returns

by attracting investments in the financial and other capital intensive sectors.

17

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

Human Capital Development

Human capital has been shrinking in Puerto Rico as its population ages and

the number of people migrating to mainland has increased. Failure to invest in the

retention and development of human capital can lead to and continue to exacerbate

existing high levels of poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, and other social ills.

Compared to the rest of Latin America, Puerto Rico has historically made

substantial educational investments, making it sixth in world in higher education enrollment, with a strong emphasis on science and engineering (Griffin, et

al., 2011). However, recent initiatives may counter this comparative advantage as

spending cuts have been pushed throughout Puerto Ricos education system from

primary schooling through post-secondary education.

Puerto Rico should act to ensure that investments in education are not re-

duced and should combine them with skill-training programs to make more skilled

labor available to specifically-targeted industries that look to expand within or to

Puerto Rico. Although Puerto Rico has had some success in the field of engineering, there are numerous opportunities for improvement. A recent shift in emphasis

towards targeted hiring credits should be reconsidered, both because specific hiring

credits have been found to have little effect (Neumark, 2013) and because sectoral

job training programs have been substantially more successful throughout the U.S.

(Michigan Department of Licensing, 2010; MacGuire, et al., 2010).

Poverty and inequality have been reduced due to the increase in transfer

payments and public assistance programs from both the U.S. Federal Government

as well as Puerto Rico, as can be demonstrated in the Tables of the Appendix. However, the rapid expansion of government transfers in 1970s and early 1980s had a

18

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

simultaneous effect of reducing work effort. Puerto Ricans essentially have developed a reservation wage that has depressed job creation, which compares what

could be earned on the mainland or through public assistance and places a floor

upon market wages (Collins, et al., 2006). For this reason, Puerto Ricos labor participation rate has fallen from nearly 50 percent before the 2000s to a current low

of below 40 percent. In order to combat this problem, without furthering inequality

and poverty, the programs should be redesigned to make them more conducive to

employment gains.

Deregulation

Like many other Latin American countries, Puerto Rico has had a long his-

tory of high barriers to business creation. Both the previous governor and the current one have cited the problems associated with a complex bureaucracy and its

impact on business development and competition, while economists have cited the

cumbersome permitting process as an impediment to business activity (Collins,

et al., 2006). High energy and transportation costs add to these compliance costs,

making it oftentimes more costly to do business than in other parts of the U.S.,

while excessive labor laws have also made for an inefficient labor market.

Fiscal Policy

Due to Puerto Ricos lack of control over monetary policy, some suggest

that it has excessively used its fiscal authority to attempt to stimulate its economy.

Puerto Rico has borrowed against future revenues for decades, despite the islands

balanced budget requirement, which is having a crowding out effect on private activity through the increased cost of productive resources. Furthermore, its relatively high rate of debt and unfunded pensions have substantially increased the risk of

19

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

a fiscal crisis similar to the debt crisis in Latin America during the 1980s, in which

total debt owed to foreigners outweighed its ability to earn income, resulting in an

unsustainable economic outlook.

Macroeconomic modeling has long suggested that when interest rates on an

economys debt exceeds its current and projected growth rate, it becomes impossible for an economy to fully recover (Blanchard & Weil, 2001). Few economists

will concede the possibility of Puerto Ricos growth rate reaching or exceeding existing interest rates that lenders are willing to offer Puerto Rico, given its currently

perceived riskiness for default.

Status

One of the key debates surrounding Puerto Ricos economy is the impact

that a change in its status will have. While Puerto Rico is currently considered an

autonomous territory of the U.S., three groups of advocates surround this issue:

those who wish to maintain the status quo, those vying for the creation of an independent country, and those who believe that Puerto Rico should become the 51st

state of the United States. As most recent debates revolve around the possibility of

statehood, this paper will continue with a brief discussion on its economic implications.

There are numerous arguments, both for and against, Puerto Rico statehood.

Economic arguments for statehood have suggested that, where capital intensive

industry development has failed, a Puerto Rican state would have a similar fate

to that of Hawaii. When Hawaii first became a state, it reaped rapid rewards by

quickly developing a substantial service sector due to its new connection to the U.S.

and free marketing received from the statehood process (Gerow, 2014). Puerto

Rico may also benefit from an employment boost from a labor-intensive industry

and would be afforded the higher public assistance and transfer payment bene-

20

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

fits that states currently receive, which may substantially contribute to reducing

poverty and income inequality (as was the result of similar increases in the 1970s

and 1980s). Contrarily, the substantial increase in public assistance benefits could

further contribute to the depressed labor market and incentive for accepting labor

market wages, while increased federal taxes on businesses could also depress economic activity, both domestically and from foreign investments.

Considering the political rift among Puerto Ricos legislators its appointed

representative in D.C. advocates for statehood, while its governor prefers the status

quo it may be unlikely that a permanent decision will be reached until greater

political unity is achieved. However, it should be noted that future investors, and

even native Puerto Ricans considering their own residency and investments, may

consider the rift a sign of continued economic instability and uncertainty. Regardless of the outcome, there will be economic benefits to a permanent and conclusive

end to the status discussion.

Conclusion

Whether or not Puerto Rico decides to change its status in the near future,

it is clear that Puerto Rico has had a storied economic history that has led to its

currently indebted, yet opportunity-rich climate. On one side, there are those who

see Puerto Ricos fiscal situation as one of disrepair, unable to sustain itself in the

near future. However, on the other side of this negative outlook is one that, at the

very least, concedes that Puerto Ricos economy may have nowhere to go but toward improvement. Whether the bumpy road ahead is a short-run headache, or a

long-term impediment to any sign of future growth, will rest upon the shoulders of

those in power. Officials may continue to put off hard decisions for current political

victories, unite to implement a tough, yet fruitful, long-term economic plan, or have

their hands forced due to a painful economic collapse.

21

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

References

Abel, J. & Deitz, R. (2014). The Causes and Consequences of Puerto Ricos Declining Population. Current Issues in Economics & Finance, 20(4), 1-8.

Ayala, C. J., & Bernabe, R. (2007). Puerto Rico in the American century: A history since 1898. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Blanchard, O. & Weil, P. (2001). Dynamic Efficiency, the Riskless Rate, and Debt

Ponzi Games under Uncertainty. Advances in Macroeconomics, 1(2), 1.

Caribbean Business Editorial Board (2015, January 11). The Economist forecast:

PR among worlds weakest economies in 2015. Retrieved February 23,

2015, from http://www.caribbeanbusinesspr.com/news/the-economist-forecast-pr-among-worlds-weakest-economies-in-2015-103074.html

Casey, N. (2012, November 5). In Puerto Rico, a Governor Pushes Big Change.

The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved May 10, 2014, from http://online.wsj.

com/news/articles/SB1000142405297020478930457808698

Colegio de Contadores Pblicos Autorizados de Puerto Rico (2014). Informe del

Comit de Recomendaciones para la Recuperacin Econmica de Puerto

Rico. Puerto Rico: Colegio CPA.

Collins, S. M., Bosworth, B., & Soto-Class, M. A. (2006). The economy of Puerto

Rico: Restoring growth. San Juan, P.R: Center for the New Economy.

El Nuevo Da Editorial Board (2015, February 3). Puerto Rico Est en Quiebra.

Retrieved February 23, 2015, from http://www.elnuevodia.com/noticias/

locales/nota/puertoricoestaenquiebra-2002768/

Federal Reserve System. (2010). District Profile of Puerto Rico. Retrieved May 3,

2014, from http://www.newyorkfed.org/regional/profile_pr.html

Fernandez, R. (1995). The Disenchanted Island, Puerto Rico and the United States

in the 20th Century. Hispanic American Historical Review, 75(3), 518-519.

Franko, P. (2007). The Puzzle of Latin American Economic Development (3rd

ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

Government Accountability Office (GAO). (1992). Pharmaceutical Industry: Tax

Benefits of Operating in Puerto Rico 3. Retrieved May 10, 2014, from

http://www.gao.gov/assets/80/78407.pdf

Government Accountability Office (GAO). (2006). Fiscal relations with the Federal Government and economic trend during the phase out of the Possessions tax credit. Report to the Chairman and Ranking Minority Member,

Committee on Finance, U.S. Senate. Retrieved May 10, 2014, from http://

www.gao.gov/products/GAO-06-541

22

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

Greece in the Caribbean. (2013, October 26). The Economist. Retrieved May 10,

2014, from http://www.economist.com/news/leaders/21588374-stuck-realdebt-crisis-its-back-yard-america-can-learn-europes-aegean

Greene, D. (2013, February 6). Puerto Ricos Battered Economy: The Greece

Of The Caribbean?. NPR. Retrieved May 10, 2014, from http://

www.npr.org/2013/02/06/171071377/puerto-ricos-battered-economy-the-greece-of-the-caribbean

Griffin, M., Annulis, H., McCearley, T., Green, D., Kirby, C., & Gaudet, C.

(2011). Analysis of human capital development in Puerto Rico: summary

and conclusions. Human Resource Development International, 14(3), 337346.

Government Development Bank of Puerto Rico. (2015). Economy and Economic

Indicators. Commonwealth of Puerto Rico. Retrieved January 20, 2015,

from http://www.gdb-pur.com/

Gerow, A. E. (2014). Shooting for the Stars (and Stripes): How Decades of Failed

Corporate Tax Policy Contributed to Puerto Ricos Historic Vote in Favor

of Statehood. Tulane Law Review, 88(3), 627-650.

Guerrero, R. (2004). The Increasing Income Gap between Rich and Poor in

Puerto Rico. University of Puerto Rico, Graduate School of Planning.

Retrieved May 10, 2014, from http://graduados.uprrp.edu/planificacion/

facultad/rafael-corrada/increasing_income_gap_pr.pdf

Harvard Law Review (2015). Municipal Bankruptcy PremptionPuerto Rico

Passes New Municipal Reorganization Act. Harvard Law Review, 128(4),

1320-1327.

Kuriloff, A. (2015, February 19). Moodys Cuts Puerto Rico Rating Further into

Junk. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved February 23, 2015, from http://

www.wsj.com/articles/moodys-cuts-puerto-rico-rating-further-intojunk-1424381800

Maguire, S., Freely, J., Clymer, C., Conway, M., and Schwartz, D. (2010). Tuning In to Local Labor Markets: Findings from the Sectoral Employment

Impact Study, Executive Summary. Public/ Private Ventures Publications,

Philadelphia. Retrieved December 2, 2013, from http://www2.oaklandnet.

com/oakca/groups/ceda/documents/report/dowd021455.pdf

Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory Affairs. (2010). Latest Report Shows 75 Percent of NWLB Workers Obtained, Retained a Job As a

Result of Training. Michigan Department of Licensing and Regulatory

Affairs, 29 June, 2010. Retrieved December 2, 2013, from http://www.

michigan.gov/lara/0,4601,7-154-10573_11472-239530--,00.html

23

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

Neumark, D. (2013). Spurring Job Creation in Response to Severe Recessions:

Reconsidering Hiring Credits. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32 (1):142-171.

Public Law 111148. (2010). The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

111th United States Congress. Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office. Retrieved January 25, 2015 from http://www.gpo.

gov/fdsys/granule/PLAW-111publ148/PLAW-111publ148/content-detail.

html

Segarra, E. (2006). What happened to the distribution of income in Puerto Rico

during the last three decades of the xx century? A statistical point of view.

Essay 129. University of Puerto Rico, Department of Economics. Retrieved May 1, 2014, from http://economia.uprrp.edu/ensayo%20129.pdf

Slavin, R. (2014, May 12). Puerto Rico Plan Aims to Reboot Economy. The

Bond Buyer. Retrieved December 10, 2014, from http://www.bondbuyer.com/issues/123_90/puerto-rico-plan-aims-to-reboot-islands-economy-1062350-1.html

Sotomayor, O. J. (1996). Poverty and Income Inequality in Puerto Rico, 1969-89:

Trends and Sources. Review of Income & Wealth, 42(1), 49-61.

U.S. Department of Commerce, U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). American Community Survey (ACS). Retrieved May 1, 2014, from http://factfinder2.census.

gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/wc_acs.html

U.S. Department of Labor. (2015). Unemployment rate demographics, 1976-2015.

In U.S. Department of Labor- Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved February 10, 2015 from http://data.bls.gov/pdq/SurveyOutputServlet

Velez, G. (2011). Reinvencion boricua: Propuestas de reactivacion economica

para los individuos, las empresas y el gobierno. San Juan, P.R.: Inteligencia Econmica.

Vlez-Hagan, J. & Finger, R. (2013, December 1). Default: Puerto Ricos Inevitable Option. Forbes. Retrieved May 5, 2014, from http://www.forbes.com/

sites/richardfinger/2013/12/01/default-puerto-ricos-inevitable-option/

Weisskoff, R. (1985). Factories and food stamps: The Puerto Rico model of development. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

World Factbook. (2014, April 14) Puerto Rico. CIA Library. Retrieved February

5, 2015, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/rq.html

24

Copyright The National Puerto Rican Chamber of Commerce

Appendix: Data Tables

Table 1

Percentage of Household Income from Earnings, Social Security and Public

Assistance

(Household Average)

1970

1980

1990

2000

% of Household income from earnings

77

61

61

59

% of Household income from Social Security

13

21

21

21

10

95

90

94

90

% of Household income from Public Assistance

Total

Source: (Segarra, 2006)

Table 2

Gini Coefficients for Household Income and

Household Earnings, 1970-2000

Year

Household

income

%

Change

Household

Earnings

%

Change

1970

0.545

1980

0.512

-5.9

0.65678

6.8

1990

0.506

-1.2

0.66313

1.0

2000

0.564

11.4

0.69129

4.2

0.61504

Source: (Segarra, 2006)

Table 3

Gini Coefficients for total household income, with exclusions 1970-2000

Year

Total

Household

income

%

Change

Total

Household

Income

(Excluding

Social

Security

Income)

%

Change

Household

Income

(Excluding

Public

Assistance

Income)

%

Change

1970

0.560

1980

0.512

-8.4

0.592

-0.4

0.535

-5.2

1990

0.500

-2.4

0.583

-1.5

0.543

1.5

2000

0.564

12.7

0.638

9.4

0.581

6.9

0.595

0.565

Source: (Segarra, 2006)

25

This paper has been produced and presented by

For inquiries, please send an email to: Info@NPRChamber.org

You might also like

- J. Tomas Hexner and Glenn Jenkins - Self-Determination Will Reduce The $13 Billion - Puerto Rico The Economic and Fiscal DimensionsDocument44 pagesJ. Tomas Hexner and Glenn Jenkins - Self-Determination Will Reduce The $13 Billion - Puerto Rico The Economic and Fiscal DimensionsJavier Arvelo-Cruz-SantanaNo ratings yet

- PuertoRico BerindesDocument3 pagesPuertoRico BerindesJay PinedaNo ratings yet

- NotiCel Analisis Wells Fargo Mayo 2012Document18 pagesNotiCel Analisis Wells Fargo Mayo 2012noticelmesaNo ratings yet

- Subtopic MunDocument7 pagesSubtopic MunrouakatayaNo ratings yet

- Economic Issues of Puerto Rico OfficialDocument10 pagesEconomic Issues of Puerto Rico Officialroweco7480No ratings yet

- Treasury Letter - 7.29.16-MuddDocument19 pagesTreasury Letter - 7.29.16-MuddJohn E. MuddNo ratings yet

- Carta de Lew A RyanDocument2 pagesCarta de Lew A RyanMetro Puerto RicoNo ratings yet

- Studies and PERSPECTIvesDocument41 pagesStudies and PERSPECTIvesIsraelNo ratings yet

- The Benefit and The Burden: Tax Reform-Why We Need It and What It Will TakeFrom EverandThe Benefit and The Burden: Tax Reform-Why We Need It and What It Will TakeRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- Taxing Puerto RicansDocument62 pagesTaxing Puerto RicansJavier Arvelo-Cruz-SantanaNo ratings yet

- Unit 3 PortDocument10 pagesUnit 3 Portapi-384645648No ratings yet

- Juracan Vol1 - No1 - 11x17Document2 pagesJuracan Vol1 - No1 - 11x17Virtual BoricuaNo ratings yet

- Dietz, James. "Economic History of Puerto Rico: Institutional Change and Capitalist Development". (1987)Document5 pagesDietz, James. "Economic History of Puerto Rico: Institutional Change and Capitalist Development". (1987)JenniferGonzálezSotoNo ratings yet

- Carta A Joe ManchinDocument4 pagesCarta A Joe ManchinEl Nuevo DíaNo ratings yet

- Carta de La Junta Sobre El Plan Fiscal Del Gobierno CentralDocument8 pagesCarta de La Junta Sobre El Plan Fiscal Del Gobierno CentralEl Nuevo Día100% (1)

- RRossello - A Sustainable Solution To Puerto Rico's Fiscal CrisisDocument10 pagesRRossello - A Sustainable Solution To Puerto Rico's Fiscal CrisisRicardo Rossello100% (4)

- Foreign and Economic Policies of The Philippines (Inc)Document26 pagesForeign and Economic Policies of The Philippines (Inc)Ken CadanoNo ratings yet

- Puerto Rico There Is A Better WayDocument18 pagesPuerto Rico There Is A Better WayJohn E. MuddNo ratings yet

- Local TaxationDocument29 pagesLocal Taxationdlo dphroNo ratings yet

- Promesa Has Failed: How A Colonial Board Is Enriching Wall Street and Hurting Puerto RicansDocument77 pagesPromesa Has Failed: How A Colonial Board Is Enriching Wall Street and Hurting Puerto RicansACRE CampaignsNo ratings yet

- BG Puerto Rico Tax HeavenDocument4 pagesBG Puerto Rico Tax HeavenjuanmoczoNo ratings yet

- Hiram Melendez-In The Red-Puerto RicoDocument8 pagesHiram Melendez-In The Red-Puerto RicoalexbetancourtNo ratings yet

- Reform-of-the-Economic-Provisions-UP-School-of-EconomicsDocument23 pagesReform-of-the-Economic-Provisions-UP-School-of-EconomicsTomoyo AdachiNo ratings yet

- Carta de La Junta Al Gobernador Ricardo Rosselló Sobre Los Cambios Al Plan FiscalDocument7 pagesCarta de La Junta Al Gobernador Ricardo Rosselló Sobre Los Cambios Al Plan FiscalEl Nuevo Día100% (2)

- FOMB - Statement - POADocument3 pagesFOMB - Statement - POAFran Javier SolerNo ratings yet

- Structural Change in The Economy of Puerto RicoDocument126 pagesStructural Change in The Economy of Puerto RicoElias GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Cut, Balance, and GrowDocument24 pagesCut, Balance, and GrowTeamRickPerryNo ratings yet

- The Role of The State and Public Finance in The Next GenerationDocument28 pagesThe Role of The State and Public Finance in The Next Generationsolanki YashNo ratings yet

- Activity 3 in HistoryDocument4 pagesActivity 3 in HistoryAngelito Garcia Jr.No ratings yet

- Pizza Hut in BrazilDocument5 pagesPizza Hut in BrazilShaté Itminan100% (1)

- SPEECH: Statement, Committee On The Budget, Comments On The President's FY 2010 BudgetDocument4 pagesSPEECH: Statement, Committee On The Budget, Comments On The President's FY 2010 BudgetpedropierluisiNo ratings yet

- Plan B: The Economic Development of the Eastern Region of Puerto Rico Through the Decolonization of ViequesFrom EverandPlan B: The Economic Development of the Eastern Region of Puerto Rico Through the Decolonization of ViequesNo ratings yet

- Taxes TribeDocument17 pagesTaxes TribepablojhrNo ratings yet

- The Neoclassical Counterrevolution and Developing Economies: A Case Study of Political and Economic Changes in The PhilippinesDocument9 pagesThe Neoclassical Counterrevolution and Developing Economies: A Case Study of Political and Economic Changes in The PhilippinesEd ViggayanNo ratings yet

- The United States and the PROMESA to Puerto Rico: an analysis of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability ActFrom EverandThe United States and the PROMESA to Puerto Rico: an analysis of the Puerto Rico Oversight, Management, and Economic Stability ActNo ratings yet

- Growth Without Poverty Reduction: The Case of Costa RicaDocument8 pagesGrowth Without Poverty Reduction: The Case of Costa RicaCato InstituteNo ratings yet

- Budget of the U.S. Government: A New Foundation for American Greatness: Fiscal Year 2018From EverandBudget of the U.S. Government: A New Foundation for American Greatness: Fiscal Year 2018No ratings yet

- MERCOSUR and NAFTA - The Need For ConvergenceDocument8 pagesMERCOSUR and NAFTA - The Need For Convergencetranvanhieupy40No ratings yet

- Activity 3Document3 pagesActivity 3Angelito Garcia Jr.No ratings yet

- Prez PoliticalEconomyContemporary 2022Document16 pagesPrez PoliticalEconomyContemporary 2022danielchai16No ratings yet

- SOCSCI031CANARESDocument3 pagesSOCSCI031CANARESFearless CnrsNo ratings yet

- FINAL - Lessons From States - August 2019 - IRGDocument10 pagesFINAL - Lessons From States - August 2019 - IRGAnonymous 5cXDMwzqNo ratings yet

- Pain and ProfitDocument12 pagesPain and ProfitLatino RebelsNo ratings yet

- United States District Court District of Puerto RicoDocument8 pagesUnited States District Court District of Puerto RicoEmily RamosNo ratings yet

- RR - Response To Senator Orrin Hatch - 03012016 PDFDocument9 pagesRR - Response To Senator Orrin Hatch - 03012016 PDFAlfonso A. Orona AmiliviaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 9 - Evolution of Taxation in The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesChapter 9 - Evolution of Taxation in The PhilippinestobiasninaarzelleNo ratings yet

- Local Government Taxation in The Philippines 1220413948637399 9Document38 pagesLocal Government Taxation in The Philippines 1220413948637399 9Jojo PalerNo ratings yet

- Local Government TaxationDocument16 pagesLocal Government TaxationReychelle Marie BernarteNo ratings yet

- Governor Rick Perry - Cut Balance and Grow - Full Economic and Tax PlanDocument24 pagesGovernor Rick Perry - Cut Balance and Grow - Full Economic and Tax PlanZim VicomNo ratings yet

- EconomyDocument6 pagesEconomyDrakeson LlaneraNo ratings yet

- Cost of Government Day - 2011Document48 pagesCost of Government Day - 2011smooviesmooveNo ratings yet

- 2trade LiberalizationDocument14 pages2trade LiberalizationKTW gamingNo ratings yet

- The Road to Prosperity: How to Grow Our Economy and Revive the American DreamFrom EverandThe Road to Prosperity: How to Grow Our Economy and Revive the American DreamNo ratings yet

- Topic 2 - Economic system (Group 2) - Nguyễn Ngọc Bảo Hiếu - Nguyễn Ngọc Mỹ Thy - Mạc Như Giang - Mai Vũ Gia Hưng - Phan Sỹ Tùng LongDocument10 pagesTopic 2 - Economic system (Group 2) - Nguyễn Ngọc Bảo Hiếu - Nguyễn Ngọc Mỹ Thy - Mạc Như Giang - Mai Vũ Gia Hưng - Phan Sỹ Tùng LongMinhh KhánhhNo ratings yet

- Syllabus MIT - Dr. Diane DavisDocument16 pagesSyllabus MIT - Dr. Diane DavisPLAN6046No ratings yet

- Streeten On Dichotomies of DevelopmentDocument25 pagesStreeten On Dichotomies of DevelopmentArtist AgustinNo ratings yet

- JournalsDocument6 pagesJournalsharmen-bos-9036No ratings yet

- API Ny - GDP.MKTP - KD Ds2 en Excel v2 2055890Document73 pagesAPI Ny - GDP.MKTP - KD Ds2 en Excel v2 2055890Nisrina CitraNo ratings yet

- External Debt and Economic Growth: Evidence From Sierra LeoneDocument116 pagesExternal Debt and Economic Growth: Evidence From Sierra LeoneSahr Ibrahim KambaimaNo ratings yet

- BusinessDocument12 pagesBusinessLorrente LopezNo ratings yet

- Women, Peace and Security Index Report 2017Document84 pagesWomen, Peace and Security Index Report 2017Cronista.comNo ratings yet

- API NY - GDP.MKTP - KD DS2 en Excel v2 3159007Document74 pagesAPI NY - GDP.MKTP - KD DS2 en Excel v2 3159007krishbalu17No ratings yet

- A Human Development and Capability Approach To Food Security: Conceptual Framework and Informational BasisDocument46 pagesA Human Development and Capability Approach To Food Security: Conceptual Framework and Informational BasisPasquale De MuroNo ratings yet

- Course Content PDFDocument153 pagesCourse Content PDFAbid HussainNo ratings yet

- EGD Project Topics PDFDocument2 pagesEGD Project Topics PDFAKSHIT JAINNo ratings yet

- 4 PsDocument17 pages4 PsJad DizonNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Fill Your Research Proposal QuestionnaireDocument226 pagesA Guide To Fill Your Research Proposal QuestionnairedatateamNo ratings yet

- Was Stalin Necessary For Russia S Economic Development?Document64 pagesWas Stalin Necessary For Russia S Economic Development?Tomás AguerreNo ratings yet

- Growth and Inequality in India With KeithDocument24 pagesGrowth and Inequality in India With KeithDipankar ChakravartyNo ratings yet

- This Syllabus Was Patterned From The Term 2 AY 2011-2012 Syllabus of Mr. Redencio B. Recio With Consent. Slight Modifications Were MadeDocument8 pagesThis Syllabus Was Patterned From The Term 2 AY 2011-2012 Syllabus of Mr. Redencio B. Recio With Consent. Slight Modifications Were MadeClyde CazeñasNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Development EconomicsDocument16 pagesIntroduction To Development EconomicsMAPNo ratings yet

- Guide DataDocument331 pagesGuide DataHiroaki OmuraNo ratings yet

- Food Security Analysis in Islamic Economic PerspectiveDocument21 pagesFood Security Analysis in Islamic Economic PerspectivefadilaNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSIDocument8 pagesInternational Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention (IJHSSIinventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Pop Lecture 206Document22 pagesPop Lecture 206jabbamikeNo ratings yet

- Case Study Palm Oil PDFDocument126 pagesCase Study Palm Oil PDFfazz133No ratings yet

- Basant Rakesh: Educational QualificationsDocument13 pagesBasant Rakesh: Educational QualificationsVishalNagarkotiNo ratings yet

- Urban Informal Sector: A Case Study of Street Vendors in KashmirDocument4 pagesUrban Informal Sector: A Case Study of Street Vendors in KashmirMikoNo ratings yet

- The Role of Mobile Phones in Sustainable Rural Poverty ReductionDocument18 pagesThe Role of Mobile Phones in Sustainable Rural Poverty ReductionChidi CosmosNo ratings yet

- Postgraduate Programme in Management Ec1205: Indian EconomyDocument4 pagesPostgraduate Programme in Management Ec1205: Indian EconomyPhaneendra SaiNo ratings yet

- Theories of DevelopmentDocument5 pagesTheories of DevelopmentJahedHossain100% (1)

- Chapter No.1Document22 pagesChapter No.1Kamal Singh100% (2)

- 32 .Solomon GoshuDocument83 pages32 .Solomon GoshuTesfaye Teferi ShoneNo ratings yet

- Knec Technical Exam Timetable - July 2017Document18 pagesKnec Technical Exam Timetable - July 2017romwama100% (1)

- Meier, Frontiers of Development Economics, 2001 PDFDocument585 pagesMeier, Frontiers of Development Economics, 2001 PDFAnna BonNo ratings yet