Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Monty Python's Flying Circus

Uploaded by

catalinatorreCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Monty Python's Flying Circus

Uploaded by

catalinatorreCopyright:

Available Formats

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Monty Python's Flying Circus

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Monty Pythons Flying Circus (known during the

final series as just Monty Python) is a British sketch

comedy series commissioned by David

Attenborough,[1] created by the comedy group Monty

Python and broadcast by the BBC from 1969 to 1974.

The shows were composed of surreality, risqu or

innuendo-laden humour, sight gags and observational

sketches without punchlines. It also featured

animations by Terry Gilliam, often sequenced or

merged with live action. The first episode was

recorded on 7 September and broadcast on 5 October

1969 on BBC One, with 45 episodes airing over four

series from 1969 to 1974, plus two episodes for

German TV.

The show often targets the idiosyncrasies of British

life, especially that of professionals, and is at times

politically charged. The members of Monty Python

were highly educated. Terry Jones and Michael Palin

are Oxford University graduates; Eric Idle, John

Cleese, and Graham Chapman attended Cambridge

University; and American-born member Terry Gilliam

is an Occidental College graduate. Their comedy is

often pointedly intellectual, with numerous erudite

references to philosophers and literary figures. The

series followed and elaborated upon the style used by

Spike Milligan in his ground breaking series Q5,

rather than the traditional sketch show format. The

team intended their humour to be impossible to

categorise, and succeeded so completely that the

adjective "Pythonesque" was invented to define it and,

later, similar material.

The Pythons play the majority of the series characters

themselves, including the majority of the female

characters, but occasionally they cast an extra actor.

Regular supporting cast members include Carol

Cleveland (referred to by the team as the unofficial

"Seventh Python"), Connie Booth (Cleese's first wife),

series Producer Ian MacNaughton, Ian Davidson, Neil

Innes (in the fourth series), and the Fred Tomlinson

Singers (for musical numbers).

The series' theme song is the first segment of John

Philip Sousa's The Liberty Bell, chosen because it was

in the public domain and thus could be used without

charge.

Contents

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

Monty Pythons Flying Circus

Genre

Sketch comedy

Surreal comedy

Satire

Black comedy

Created by

Graham Chapman

John Cleese

Terry Gilliam

Eric Idle

Terry Jones

Michael Palin

Written by

Monty Python

Neil Innes

Douglas Adams

Directed by

Ian MacNaughton

John Howard Davies

Starring

Graham Chapman

John Cleese

Terry Gilliam

Eric Idle

Terry Jones

Michael Palin

With

Carol Cleveland

Ian Davidson

Connie Booth

Opening

theme

"The Liberty Bell" by John Philip

Sousa

Composer(s) Neil Innes

Fred Tomlinson Singers

Country of

United Kingdom

1/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Contents

origin

No. of series 4

1 Title

2 Recurring characters

No. of

episodes

2.1 Frequently recurring characters (six

or more appearances)

2.2 Characters who made multiple

Production

Running

time

appearances

3 Popular character traits

3.1 Chapman

3.2 Cleese

3.3 Gilliam

3.4 Idle

3.5 Jones

3.6 Palin

45 (List of episodes)

approx. 2530 minutes

Broadcast

Original

channel

BBC1 (19691973)

BBC2 (1974)

Original run 5October1969 5December1974

Chronology

Followed by And Now for Something

Completely Different

4 Lost sketches

5 Monty Python's Fliegender Zirkus

6 Stage incarnations

7 Landing of Flying Circus

8 Awards and honours

9 Legacy

10 Production

11 Transnational Themes in Monty Python's

Flying Circus

12 See also

13 References

14 External links

Title

The title Monty Python's Flying Circus was partly the result of the group's reputation at the BBC.

Michael Mills, the BBC's Head of Comedy, wanted their name to include the word "circus" because the

BBC referred to the six members wandering around the building as a circus, in particular "Baron Von

Took's Flying Circus", after Barry Took, who had brought them to the BBC.[2] The group added "flying"

to make it sound less like an actual circus and more like something from World War I. The group was

coming up with their name at a time when the 1966 Royal Guardsmen song Snoopy vs. the Red Baron

had been at a peak. Manfred von Richthofen, the WWI German flying ace known as The Red Baron,

commanded a squadron of planes known as "The Flying Circus." The words "Monty Python" were

added because they claimed it sounded like a really bad theatrical agent, the sort of person who would

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

2/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

have brought them together, with John Cleese suggesting "Python" as something slimy and slithery, and

Eric Idle suggesting "Monty".[3] They later explained that the name Monty "...made us laugh because

Monty to us means Lord Montgomery, our great general of the Second World War".[4]

The BBC had rejected some other names put forward by the group including Whither Canada?, The

Nose Show, Ow! It's Colin Plint!, A Horse, a Spoon and a Basin, The Toad Elevating Moment and Owl

Stretching Time.[3] Several of these titles were later used for individual episodes.

Recurring characters

In contrast to many other sketch comedy shows, Flying Circus had only a handful of recurring

characters, many of whom were involved only in titles and linking sequences. Continuity for many of

these recurring characters was frequently non-existent from sketch to sketch, with sometimes even the

most basic information (such as a character's name) being changed from one appearance to the next.

Frequently recurring characters (six or more appearances)

The "It's" Man (Palin), a Robinson Crusoe-type castaway with torn clothes and a long, unkempt

beard who would appear at the beginning of the programme. Often he is seen performing a long or

dangerous task, such as falling off a tall, jagged cliff or running through a mined field a long

distance towards the camera before introducing the show by just saying, "It's..." before being

abruptly cut off by the opening titles and Terry Gilliam's animation sprouting the words 'Monty

Pythons Flying Circus'. It's was an early candidate for the title of the series.

A BBC continuity announcer in a dinner jacket (Cleese), seated at a desk, often in highly

incongruous locations, such as a forest or a beach. His line, "And now for something completely

different," was used variously as a lead-in to the opening titles and a simple way to link sketches.

Though Cleese is best known for it, Idle first introduced the phrase in Episode 2, where he

introduced a man with three buttocks. It eventually became the shows catch phrase and served as

the title for the troupes first movie. In Series 3 the line was shortened to simply: "And now..." and

was often combined with the "It's" man in introducing the episodes.

The Gumbys, a group of slow-witted individuals identically attired in gumboots (from which they

take their name), high-water trousers, braces, and round, wire-rimmed glasses, with toothbrush

moustaches and knotted handkerchiefs worn on their heads (a stereotype of the English, working

class holidaymaker). They hold their arms stiffly at their sides, speak slowly in loud, throaty

voices punctuated by frequent grunts and groans, and have a fondness for pointless violence. All

of them are surnamed Gumby: D.P. Gumby, R.S. Gumby, etc. Even though all Pythons played

Gumbys in the show's run, the character is most closely associated with Michael Palin.

The Knight with a Raw Chicken (Gilliam), who would hit characters over the head with the

chicken when they said something particularly silly. The knight was a regular during the first

series and made another appearance in the third.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

3/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A nude organist (played in his first appearance by Gilliam, later by Jones) who provided a brief

fanfare to punctuate certain sketches, most notably on a sketch poking fun at Sale of the Century

or as yet another way to introduce the opening titles. This character was addressed as "Onan" by

Palin's host character in the ersatz game show sketch "Blackmail".

The "Pepperpots" are screeching middle-aged, lower-middle class housewives, played by the

Pythons in frocks, and engage in surreal and inconsequential conversation. "The Pepperpots" was

the in-house name that the Pythons used to identify these characters, and were never identified as

such on-screen. On the rare occasion these women were named, it was often for comic effect,

featuring such names as Mrs. Scum, Mrs. Non-Gorilla, or the duo Mrs. Premise and Mrs.

Conclusion. "Pepperpot" refers to what the Pythons believed was the typical body shape of

middle-class, British housewives, as explained by John Cleese in How to Irritate People. Terry

Jones is perhaps most closely associated with the Pepperpots, but all the Pythons were frequent in

performing the drag characters.

Brief black-and-white stock footage, lasting only two or three seconds, of middle-aged women

sitting in an audience and applauding. The film was taken from a Womens Institute meeting

and was sometimes presented with a colour tint.

Characters who made multiple appearances

"The Colonel" (Chapman), a British Army officer who interrupts sketches that are "too silly" or

that contain material he finds offensive. The Colonel also appears when non-BBC broadcast

repeats need to be cut off for time constraints in syndication.

Arthur Pewtey (Palin), a socially inept, extremely dull man who appears most notably in the

"Marriage Guidance Counsellor" and "Ministry of Silly Walks" sketches. His sketches all take the

form of an office appointment with an authority figure (usually played by Cleese), which are used

to parody the officious side of the British establishment by having the professional employed in

the most bizarre field of expertise. The spelling of Pewtey's surname is changed, between

appearances.

The Reverend Arthur Belling is the vicar of St Loony-Up-The-Cream-Bun-and-Jam. He is known

for his bizarrely eccentric behaviour. In one sketch (within Series 2, played by Chapman), he

makes an appeal to the insane people of the world to drive sane people insane; and in another

sketch (within Series 3, played by Palin), he politely joins a couple and "converts" them to his

loony sect of Christianity by smashing plates on a table, shaking a baby doll, bouncing a rubber

crab from a ping-pong paddle, and spraying shaving cream all over his face.

A somewhat disreputable shopkeeper, played by Palin, is a staple of many a two-person sketch

(notably "Dead Parrot Sketch"). He often speaks with a strong Cockney accent, and has no

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

4/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

consistent name.

Mr. Badger (Idle), a Scotsman whose speciality was interrupting sketches ('I won't ruin your

sketch, for a pound'). He was once interviewed, in a sketch opposite Cleese, regarding his

interpretation of the Magna Carta, which Badger believes was actually a piece of chewing gum on

a bedspread in Dorset. He has also been seen as an aeroplane hijacker whose demands grow

increasingly eccentric.

Mr. Eric Praline, an eccentric, disgruntled man, played by Cleese and who often wears a Pac-aMac. His most famous appearance is in the "Dead Parrot". His name is only mentioned once onscreen, during the "Fish Licence" sketch, but his attire (together with Cleese's distinctive, nasal

performance) distinguishes him as a recognizable character who makes multiple appearances

throughout the first two series. An audio re-recording of "Fish Licence" also reveals that he has

multiple pets of wildly differing species, all of them named "Eric".

Mr. Cheeky, a well-dressed moustachioed man, referred to in the published scripts as "Mr. Nudge"

(Idle), who pointedly annoys uptight characters (usually Jones). He is characterized by his

constant nudging gestures and cheeky innuendo. His most famous appearance is in his initial

sketch, "Nudge Nudge", though he appears in several later sketches too, including "The Visitors",

where he claimed his name was Arthur Name.

Biggles (Chapman, and in one instance Jones), a WWI pilot. Derived from the famous series of

fiction stories by W. E. Johns.

Luigi Vercotti (Palin), a mafioso entrepreneur and pimp featured during the first series,

accompanied in his first appearance by his brother Dino (Jones). He appears as the manager for

Ron Obvious, the owner of La Gondola restaurant and as a victim of the Piranha Brothers . With

his brother, he attempts to talk the Colonel into paying for protection of his Army base.

The Spanish Inquisition would burst into a previously unrelated sketch whenever their name was

mentioned. Their catchphrase was 'Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!' They consist of

Cardinal Ximinez (Palin), Cardinal Fang (Gilliam), and Cardinal Biggles (Jones). They premiered

in series two and Ximinez had a cameo in "The Buzz Aldrin Show".

Frenchmen: Cleese and Palin would sometimes dress in stereotypical French garb, e.g. striped

shirt, tight pants, beret, and speak in garbled French, with incomprehensible accents. They had one

fake mustache between them, and each would stick it onto the other's lip when it was his turn to

speak. They appear giving a demonstration of the technical aspects of the flying sheep in episode

2 ("Sex and Violence"), and appear in the Ministry of Silly Walks sketch as the developers of "La

Marche Futile".

The Compre (Palin), a sleazy nightclub emcee in a red jacket. He linked sketches by introducing

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

5/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

them as nightclub acts, and was occasionally seen after the sketch, passing comment on it. In one

link, he was the victim of the Knight with a Raw Chicken.

Spiny Norman, a Gilliam animation of a giant hedgehog. He is introduced in Episode 1 of Series 2

in "Piranha Brothers" as an hallucination experienced by Dinsdale Piranha when he is depressed.

Later, Spiny Norman appears randomly in the background of animated cityscapes, shouting

'Dinsdale!'

Cardinal Richelieu (Palin) is impersonated by someone or is impersonating someone else. He is

first seen as a witness in court, but he turns out to be Ron Higgins, a professional Cardinal

Richelieu impersonator. He is later seen as himself impersonating Petula Clark.

Ken Shabby (Palin) appeared in his own sketch in the first series. In the second series, he appeared

in several vox populi segments. He later founded his own religion and called himself Archbishop

Shabby.

Raymond Luxury-Yacht (Chapman) is described as one of Britain's leading skin specialists. He

wears an enormous fake nose made of polystyrene. He proudly proclaims that his name, 'is spelled

"Raymond Luxury-Yacht", but it's pronounced "Throat-Warbler Mangrove"'.

A Madman (Chapman) Often appears in vox pops segments. He wears a bowler hat and has a

bushy moustache. He will always rant and ramble about his life whenever he appears and will

occasionally foam at the mouth and fall over backwards. He appears in "The Naked Ant", "The

Buzz Aldrin Show", and "It's a Living"

Other returning characters include a married couple, often mentioned but never seen, Ann Haydon-Jones

and her husband Pip. In "Election Night Special", Pip has lost a political seat to Engelbert Humperdinck.

Several recurring characters are played by different Pythons. Both Palin and Chapman played the

insanely violent Police Constable Pan Am. Sgt. Jones, and Palin portrayed Harry 'Snapper' Organs of Q

division. Various historical figures were played by a different cast member in each appearance, such as

Mozart (Cleese, then Palin), or Queen Victoria (Jones, then Palin, then all five Pythons in Series 4).

Some of the Pythons' real-life targets recurred more frequently than others. Reginald Maudling, a

contemporary Conservative politician, was singled out for perhaps the most consistent ridicule. ThenSecretary of State for Education and Science, and (well after the programme had ended) Prime Minister

Margaret Thatcher, was occasionally mentioned, in particular referring to Thatcher's brain as being in

her shin received a hearty laugh from the studio audience. Then-US President Richard Nixon was also

frequently mocked, as was Conservative party leader Edward Heath, prime minister for much of the

series run. The British police were also a favourite target, often acting bizarrely, stupidly, or abusing

their authority, frequently in drag.

Popular character traits

Although there were few recurring characters, and the six cast members played many diverse roles, each

perfected some character traits.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

6/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Chapman

Graham Chapman often portrayed straight-faced men, of any age or class, frequently authority figures

such as military officers, policemen or doctors. His characters could, at any moment, engage in

"Pythonesque" maniacal behaviour and then return to their former sobriety.[5] He was also skilled in

abuse, which he brusquely delivered in such sketches as "The Argument Clinic" and "Flying Lessons".

He adopted a dignified demeanour as the leading "straight man" in the Python feature films Holy Grail

(King Arthur) and Life of Brian (title character Brian).

Cleese

John Cleese played ridiculous authority figures. Gilliam claims that Cleese is the funniest of the Pythons

in drag, as he barely needs to be dressed up to look hilarious, with his square chin and 6'5" (196cm)

frame (see the "Mr. and Mrs. Git" sketch). Cleese also played intimidating maniacs, such as an instructor

in the "Self Defence Against Fresh Fruit" sketch. His character Mr. Praline, the put-upon consumer,

featured in some of the most popular sketches, most famously in "Dead Parrot". One star turn that

proved most memorable among Python fans was "The Ministry of Silly Walks", where he worked for

the eponymous government department. The sketch features some rather extravagant physical comedy

from the notoriously tall and loose-limbed Cleese. Despite its popularity, particularly among American

fans, Cleese himself particularly disliked the sketch, feeling that many of the laughs it generated were

cheap and that no balance was provided by what could have been the true satirical centrepoint. Another

of his trademarks is his over-the-top delivery of abuse, particularly his screaming "You bastard!"

Cleese often played foreigners with ridiculous accents, especially Frenchmen, most of the time with

Palin. Sometimes this extended to the use of actual French or German (such as "The Funniest Joke in the

World", "Hitler in Minehead", or "La Marche Futile" at the end of "The Ministry of Silly Walks"), but

still with a very heavy accent (or impossible to understand, as for example Hitler's speech).

Gilliam

Many Python sketches were linked together by the cut-out

animations of Terry Gilliam, including the opening titles

featuring the iconic giant foot that became a symbol of all that

was 'Pythonesque'. Gilliams unique visual style was

characterised by sudden, dramatic movements and deliberate

mismatches of scale, set in surrealist landscapes populated by

engravings of large buildings with elaborate architecture,

grotesque Victorian gadgets, machinery, and people cut from old

Sears Roebuck catalogues. Gilliam added airbrush illustrations

and many famous pieces of art. All of these elements were

combined in incongruous ways to obtain new and humorous

meanings in the tradition of surrealist collage assemblies.

The surreal nature of the series allowed Gilliams animation to

go off on bizarre, imaginative tangents. Some running gags

derived from these animations were a giant hedgehog named

Spiny Norman who appeared over the tops of buildings shouting,

"Dinsdale!", further petrifying the paranoid Dinsdale Piranha;

and The Foot of Cupid, the giant foot that suddenly squashed

things. The latter is appropriated from the figure of Cupid in the

Agnolo Bronzino painting "Venus, Cupid, Folly and Time".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

The famous Python Foot can here be

seen in its original format in the

bottom left corner of "Venus, Cupid,

Folly and Time"

7/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Notable Gilliam sequences for the show include Conrad Poohs and his Dancing Teeth, the rampage of

the cancerous black spot, The Killer Cars and a giant cat that stomps its way through London, destroying

everything in its path.

Initially only hired to be the animator of the series, Gilliam was not thought of (even by himself) as an

on-screen performer at first, being American and not very good at deep and sometimes exaggerated

English accent of his fellows. The others felt they owed him something and so he sometimes appeared

before the camera, usually in the parts that no one else wanted to play, generally because they required a

lot of make-up or involved uncomfortable costumes. The most recurrent of these was The-Knight-WhoHits-People-With-A-Chicken, a knight in armor who would walk on-set and hit another character on the

head with a plucked chicken when they said something really corny. Some of Gilliam's other on-screen

portrayals included:

A man with a stoat through his head

Cardinal Fang in "The Spanish Inquisition"

A dandy wearing only a mask, bikini underwear and a cape, in "The Visitors"

A hotel clerk in "The Cycling Tour" episode

A fat young man covered in beans in "Most Awful Family In Britain

Despite, or, according to Cleese in the DVD commentary for Life of Brian, perhaps because of, an

obviously deficient acting ability in comparison to the others, Gilliam soon became distinguished as the

go-to member for the most obscenely grotesque characters. This carried over into the Holy Grail film,

where Gilliam played King Arthur's hunchbacked page 'Patsy'.

Idle

Eric Idle is perhaps best remembered for his roles as a cheeky, suggestive playboy, "Nudge Nudge", as a

crafty, slick salesman ("Door-to-Door Joke Salesman", "Encyclopedia Salesman"), and the merchant

who loves to haggle in Monty Pythons Life of Brian. He is acknowledged as 'the master of the one-liner'

by the other Pythons. He is also considered the best singer/songwriter in the group; for example, he

wrote and performed "Always Look on the Bright Side of Life" from The Life of Brian. Unlike Jones, he

often played female characters in a more straightforward way, only altering his voice slightly, as

opposed to the falsetto shrieking used by the others. Several times, Idle appeared as upper-class, middleaged females, such as Rita Fairbanks ("Reenactment of the Battle Of Pearl Harbor") and the sexuallyrepressed Protestant wife in the "Every Sperm is Sacred" sketch, The Meaning of Life.

Because he was not from an already-established writing partnership prior to Python, Idle wrote his

sketches alone.

Jones

Although all of the Pythons played women, Terry Jones is renowned by the rest to be 'the best Rat-Bag

woman in the business'. His portrayal of a middle-aged housewife was louder, shriller, and more

dishevelled than that of any of the other Pythons. Examples of this are the "Dead Bishop" sketch, his

role as Brian's mother Mandy in Life of Brian, Mrs. Linda S-C-U-M in "Mr. Neutron" and the caf

proprietor in "Spam". Also recurring was the upper-class reserved men, in "Nudge, Nudge" and the "It's

A Man's Life" sketch, and incompetent authority figures (Harry "Snapper" Organs). He also played the

iconic Nude Organist that introduced all of series three. Generally, he deferred to the others as a

performer, but proved himself behind the scenes, where he would eventually end up pulling most of the

strings.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

8/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Palin

Michael Palin was regarded by the other members of the troupe as the one with the widest range, equally

adept as a straight man or wildly over the top character. He portrayed many working-class northerners,

often portrayed in a disgusting light: "The Funniest Joke in the World" sketch and the "Every Sperm Is

Sacred" segment of Monty Python's The Meaning of Life). In contrast, Palin also played weak-willed,

put-upon men such as the husband in the "Marriage Guidance Counsellor" sketch, or the boring

accountant in the "Vocational Guidance Counsellor" sketch. He was equally at home as the indefatigable

Cardinal Ximinez of Spain in "The Spanish Inquisition" sketch. Another high-energy character that Palin

portrays is the slick TV show host, constantly smacking his lips together and generally being overenthusiastic ("Blackmail" sketch). In one sketch, he plays the role with an underlying hint of selfrevulsion, where he wipes his oily palms on his jacket, makes a disgusted face, then continues. One of

his most famous creations was the shopkeeper who attempts to sell useless goods by very weak attempts

at being sly and crafty, which are invariably spotted by the customer (often played by Cleese), as in the

"Dead Parrot" and the "Cheese Shop" sketches. Palin is also well known for his leading role in the "The

Lumberjack Song".

Palin also often plays heavy-accented foreigners, mostly French ("La marche futile") or German ("Hitler

in Minehead"), usually alongside Cleese. In one of the last episodes, he delivers a full speech, first in

English, then in French, then in heavily accented German.

Of all the Pythons, Palin played the fewest female roles. Among his portrayals of women are: Queen

Victoria in "Michael Ellis", Debbie Katzenberg the American in Monty Python's The Meaning of Life, or

as a rural idiot's wife in the "Idiot in rural society" sketch.

Lost sketches

John Cleese was unhappy with the use of scatological humour in Python sketches. The final episode of

the third series included a sketch called "Wee-Wee Wine Tasting", which was censored following the

BBC's and Cleeses objections. The sketch involves a man taking a tour of a wine cellar where he

samples many of the wine bottles' contents, which are actually urine. Also pulled out, though for

unknown reasons, was a sketch where Cleese had hired a sculptor to carve a statue of him. The sculptor

(Chapman) had made an uncanny likeness of Cleese, except that his nose was extremely long, almost

Pinocchio size. The only clue that this sketch was cut out of the episode was in the "Sherry-Drinking

Vicar" sketch, where, towards the back of the room, a bust with an enormously long nose sits.

Some material originally recorded went missing later, such as the use of the word "masturbation" in the

"Summarize Proust" sketch (which was muted during the first airing, and later cut out entirely) or "What

a silly bunt" in the Travel Agent sketch (which featured a character [Idle] who has a speech impediment

that makes him pronounce "C"s as "B"s),[6] which was cut before the sketch ever went to air. However,

when this sketch was included in the album Monty Python's Previous Record and the Live at the

Hollywood Bowl film, the line remained intact.

Some sketches were deleted in their entirety and later recovered. One such sketch is the "Party Political

Broadcast (Choreographed)", where a Conservative Party spokesman (Cleese) delivers a party political

broadcast before getting up and dancing, being coached by a choreographer (Idle), and being joined by a

chorus of spokesmen dancing behind him. The camera passes two Labour Party spokesmen practising

ballet, and an animation features Edward Heath in a tutu. Once deemed lost, a home-recorded tape of

this sketch, captured from a broadcast from Buffalo, New York PBS outlet WNED-TV, turned up on

YouTube in 2008.[7] Another high-quality recording of this sketch, broadcast on WTTW in Chicago, has

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

9/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

also turned up on YouTube.[8] The Buffalo version can be seen as an extra on the new Region 2/4 eightdisc The Complete Monty Python's Flying Circus DVD set. The Region 1 DVD of Before The Flying

Circus, which is included in the The Complete Monty Python's Flying Circus Collector's Edition

Megaset and Monty Python: The Other British Invasion, also contains the Buffalo version as an extra.[9]

Another lost sketch is the "Satan" animation following the "Crackpot Religion" piece and the "Cartoon

Religion Ltd" animation, and preceding the "How Not To Be Seen" sketch: this had been edited out of

the official tape. Six frames of the animation can be seen at the end of the episode, wherein that

particular episode is repeated in fast-forward. A black and white 16mm film print has since turned up

(found by a private film collector in the USA) showing the animation in its entirety.

At least two references to cancer were censored, both during the second series. In the sixth episode ("It's

A Living" or "School Prizes"),Carol Cleveland's narration of a Gilliam cartoon suddenly has Michael

Palin's(?) voice dub 'gangrene' over the word cancer (although the word 'cancer' was used unedited when

the animation appeared in the movie And Now for Something Completely Different as well as the 2006

special Terry Guilliam's Personal Best). Another reference was removed from the sketch "Conquistador

Coffee Campaign", in the eleventh episode "How Not to Be Seen", although a reference to leprosy

remained intact. This line has also been recovered from the same 16mm film print as the abovementioned "Satan" animation.

A restored Region 2 DVD release of Series 14 was released in 2007, with no additional features.

Monty Python's Fliegender Zirkus

Two episodes were produced in German for WDR (Westdeutscher Rundfunk), both entitled Monty

Python's Fliegender Zirkus, the literal German translation of the English title. While visiting the UK in

the early 1970s, German entertainer and TV producer Alfred Biolek caught notice of the Pythons.

Excited by their innovative, absurd sketches, he invited them to Germany in 1971 and 1972 to write and

act in two special German episodes.

The first episode, advertised as Monty Pythons Fliegender Zirkus: Bldeln fr Deutschland ("Monty

Python's Flying Circus: Clowning around for Germany"), was produced in 1971 and performed in

German. The second episode, advertised as Monty Pythons Fliegender Zirkus: Bldeln auf die feine

englische Art ("Monty Python's Flying Circus: Clowning around in the distinguished English way"),

produced in 1972, was recorded in English and dubbed into German for its broadcast in Germany. The

original English recording was transmitted by the BBC in October 1973.

Stage incarnations

The members of Monty Python embarked on a series of stage shows during and after the television

series. These mostly consisted of sketches from the series, though they also included other famous

sketches that had preluded them. One such sketch was the Four Yorkshiremen sketch, written by Cleese

and Chapman, and performed for At Last the 1948 Show; the sketch subsequently became part of the live

Python repertoire. The shows also included songs from collaborator Neil Innes.

Recordings of four of these stage shows have subsequently appeared as separate works:

1. Monty Python Live at Drury Lane (aka Monty Python Live at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane),

released in the UK in 1974 as their fifth record album

2. Monty Python Live at City Center, performed in New York City and released as a record in 1976

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

10/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

in the US

3. Monty Python Live at the Hollywood Bowl, recorded in Los Angeles in 1980 and released as a

film in 1982

4. Monty Python Live (Mostly): One Down, Five to Go, the troupe's reunion / farewell show, ran for

10 shows at The O2 Arena in London in July 2014. The final performance on July 20 was live

streamed to movie theatres world-wide and was later released on DVD.

In 2005 a troupe of actors headed by Rmy Renoux, translated and "adapted" a stage version of Monty

Pythons Flying Circus into French. Usually the original actors defend their material very closely, but

given in this case the "adaptation" and also the translation into French (with subtitles), the group

supported this production. The adapted material sticks close to the original text, mainly deviating when

it comes to ending a sketch, something the Python members themselves changed many times over the

course of their stage performances.[10][11] Language differences also occur in the lyrics of several songs.

For example, "sit on my face" (which translated into French would be "Asseyez-vous sur mon visage")

becomes "come in my mouth".[12]

Landing of Flying Circus

John Cleese left the show after the third series. Apart from a brief voice-over for one of Gilliam's

animations in episode 41 ("Michael Ellis") and a walk-on role in drag, he did not appear in the final six

episodes that comprised series four. (However, he did receive writing credits for sketches derived from

the writing sessions for the film of Holy Grail). Neil Innes and Douglas Adams are the only two nonPythons to get writing credits in the show Innes for songs in episodes 40, 42 and 45 (and for

contributing to a sketch in episode 45), and Adams for contributing to a sketch about a doctor whose

patients are stabbed by his nurse, in episode 45. (He also had walk-on acting parts in episodes 42 and

44.) Innes frequently appeared in the Pythons' stage shows and can also be seen as Sir Robin's lead

minstrel in Monty Python and the Holy Grail and (briefly) in Life of Brian. Adams had become friends

with Graham Chapman, and they later went on to write the failed sketch show pilot Out of the Trees.

Although Cleese stayed for the third series, he claimed that he and Chapman only wrote two original

sketches ("Dennis Moore" and "Cheese Shop"), whereas he felt everything else was derivative of

previous material. Either the third series, or the fourth series, made without Cleese, are often seen as the

weakest and most uneven of the four series, by both fans and the Pythons themselves. However, with the

fourth series, the Pythons started making episodes into more coherent stories that would be a precursor

to their films, and featured Terry Gilliam onscreen more.

The final episode of Series 4 was recorded on 16 November and broadcast on 5 December 1974. That

year NBC's summer replacement series, Dean Martin's Comedyworld aired several segments from the

Python shows. This paid enough to the BBC-TV distributors, Time-Life Films, to finally pay for the

conversion of the Flying Circus programmes from PAL to the American NTSC system, and meant the

PBS stations could afford the series at last. It was an instant hit, rapidly garnering an enormous loyal cult

following nationwide that surprised even the Pythons themselves, who did not believe that their humour

was exportable without being tailored specifically, even without a language barrier.

In 1974, the PBS station KERA in Dallas was the first television station in the United States to broadcast

episodes of Monty Python's Flying Circus, and is often credited with introducing the programme to

American audiences.[13] When several episodes were broadcast by ABC in their Wide World of

Entertainment showcase in 1975, the episodes were re-edited, thus losing the continuity and flow

intended in the originals. When ABC refused to stop treating the series in this way, the Pythons took

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

11/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

them to court. Initially the court ruled that their artistic rights had indeed been violated, but it refused to

stop the ABC broadcasts. However, on appeal the team gained control over all subsequent US

broadcasts of its programmes.[14] The case also led to their gaining the rights from the BBC, once their

original contracts ended at the end of 1980.

The show also aired on MTV during the network's infancy;[15] Monty Python was part of a two-hour

comedy block on Sunday nights that also included another BBC series, The Young Ones.

In April 2006, Monty Python's Flying Circus returned to non-cable American television on PBS. In

connection with this, PBS commissioned Monty Python's Personal Best, a six-episode series featuring

each Pythons favourite sketches, plus a tribute to Chapman, who died in 1989. BBC America has aired

the series on a sporadic basis since the mid-2000s, in an extended 40-minute time slot in order to include

commercials. Independent Film Channel acquired the rights to the show in 2009, though not exclusive,

as BBC America still airs occasional episodes of the show. Independent Film Channel airs the series

uncut roughly twice a week in a late night time slot. IFC also presented a six-part documentary Monty

Python: Almost the Truth (The Lawyers Cut), produced by Terry Jones' son Bill.

Awards and honours

Monty Python's Flying Circus placed fifth on a list of the BFI TV 100, drawn up by the British Film

Institute in 2000, and voted for by industry professionals.

Time magazine included the show on its 2007 list of the "100 Best TV Shows of All Time".[16]

In a list of the 50 Greatest British Sketches released by Channel 4 in 2005, five Monty Python sketches

made the list:[17]

#2 Dead Parrot

#12 The Spanish Inquisition

#15 Ministry of Silly Walks

#31 Nudge Nudge

#49 The Lumberjack Song

In 2004[18] and 2007, Monty Python's Flying Circus was ranked #5 and #6 on TV Guide's Top Cult

Shows Ever.[19]

Legacy

The Monty Python troupe produced a number of other stage and screen productions together following

the production of this series.

Douglas Adams, creator of The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy and co-writer of the Patient Abuse

sketch, once quoted "I loved Monty Python's Flying Circus. For years I wanted to be John Cleese, I was

most disappointed when I found out the job had been taken."[20]

Lorne Michaels counts the show as a major influence on his Saturday Night Live sketches.[21] Cleese

and Palin reenacted the Dead Parrot sketch on SNL in 1997.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

12/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

In computing, the terms spam and the Python programming language[22] are both derived from the

series.

As of 2013, questions concerning the Pythons' most famous sketches are incorporated in the

examinations required of those seeking to become British citizens.[23]

Production

The production team was headed by Ian MacNaughton. Other regular team members included Hazel

Pethig (costumes), Madelaine Gaffney (makeup) and John Horton (video effects designer).

Transnational Themes in Monty Python's Flying Circus

The overall humor of Monty Python's Flying Circus is built on an inherent Britishness; it is based on

observations of British life, society, and institutions.[24] However, part of this focus is achieved through

seeing the other through a British lens. [25] [26] The often excessive generalization and utterly banal

stereotypes can be seen as a persiflage of the views held by the British public, rather than poking fun at

the cultures that were depicted. [27] This bears similarities with some contemporary comedians, such as

Sacha Baron Cohen's comedic approach in the film Borat.

For example, while American culture is not often in the foreground in many sketches, it is rather a

frequent side note in many skits. Almost all of the 45 episodes produced for the BBC contain a reference

to Americans or American culture, with 230 references total, resulting in approximately 5 references per

show, but increasing over the course of the show.[28] In total, 140 references to the American

entertainment industry are made. Entertainment tropes, such as Westerns, Film Noir, and Hollywood are

referenced 39 times. Further, there are 12 references to arts & literature, 15 to US politics, 5 to the

American military, 7 to US historical events, 12 to locations in the U.S., 7 to space & science fiction, 21

economic references, such as brands like Pan-Am, Time-Life, and Spam, and 8 sports references. Some

references do double count in various categories.[29] It is also notable that American music is regularly

heard in the show, such as the theme song to the show Dr. Kildare, but most prominently the show's

theme song (Liberty Bell March by John Philip Sousa). While American entertainment was a pervasive

cultural influence in Britain[30] at the time of the production of the series, not all references to American

culture can be seen as conscious decisions. For example, Terry Jones did not know that Spam was an

American product at the time he wrote the sketch.[31] Kevin Kern summarizes in his analysis of

references to the U.S. "that portrayals of American themes reflected three broad responses to American

hegemony: 1) minor or passing references to specific individuals, events, or products of American

culture, 2) American cultural tropes used to serve a general comedic purpose, and 3) satire aimed at

American targets, specifically U.S. economic power, the crassness or banality of American culture, or

American violence and militarism. [32] However, Kern does not see this as exhibiting anti-American

tendencies, but as a natural extension of the Pythons frequent () satirical focus on vulgarity,

banality, violence, and militarism in the United Kingdom () [33]

See also

List of Monty Python's Flying Circus episodes

Do Not Adjust Your Set

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

13/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

At Last the 1948 Show

References

Notes

1. ^ "Sir David Attenborough: 'This awful summer?" (http://www.independent.co.uk/news/people/profiles/sirdavid-attenborough-this-awful-summer-weve-only-ourselves-to-blame-7942405.html).

www.independent.co.uk. The Independent, UK broadsheet newspaper.

2. ^ The term flying circus first being applied to Baron von Richthofen's Jagdgeschwader 1

3. ^ a b Palin, Michael (2008). Diaries 19691979: the Python Years / Michael Palin. Griffin. p.650. ISBN0312-38488-2.

4. ^ "Live At Aspen" (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JpL12ilpDnQ&t=6m20s). Retrieved 10 January 2013.

5. ^ Sketches "An Appeal from the Vicar of St. Loony-up-the-Cream-Bun-and-Jam", "The One-Man Wrestling

Match", "Johann Gambolputty..." and "The Argument Clinic"

6. ^ "Travel Agent / Watney's Red Barrell" (http://www.orangecow.org/pythonet/sketches/package.htm).

www.orangecow.org. Retrieved 13 July 2009.

7. ^ Monty Python (18 December 1971). "Monty Python - political choreographer"

(http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_8Ija4Dec7o). Monty Python - political choreographer. Spiny Norman.

Retrieved 17 June 2013.

8. ^ Monty Python (18 December 1971). "Lost Sketch- Choreographed Party Political Broadcast from WTTW11" (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4KO4_feIKO0). Lost Sketch- Choreographed Party Political

Broadcast - Monty Python's Flying Circus WTTW Channel. MontyPythoNET. Retrieved 23 January 2012.

9. ^ "DVD Talk Review: The Complete Monty Python's Flying Circus - Collectors Edition Megaset"

(http://www.dvdtalk.com/reviews/35399/complete-monty-pythons-flying-circus-collectors-edition-megasetthe/). 18 November 2008.

10. ^ Rebecca Thomas (3 August 2003). "Monty Python learns French"

(http://web.archive.org/web/20030806004915/http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/3112625.stm). BBC

Online News (BBC). Archived from the original (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/entertainment/arts/3112625.stm)

on 6 August 2003. Retrieved 4 January 2010.

11. ^ Clive Davis (31 January 2005). "Monty Python's Flying Circus At Last, in French"

(http://entertainment.timesonline.co.uk/article/0,,14936-1464143,00.html). The Times Online. Retrieved

4 January 2010.

12. ^ Logan, Brian (4 August 2003). "Ce perroquet est mort: Monty Python in French? Brian Logan meets the

team behind a world first" (http://timesonline.co.uk). The Times (London). p.18. Accessed through ProQuest

(http://search.proquest.com/news/docview/246028389/135346FB80A35F1532C/1?accountid=31191), 1

March 2012.

13. ^ Peppard, Alan (2011-08-25). "Alan Peppard: Bob Wilson hailed in KERA documentary"

(http://www.dallasnews.com/entertainment/columnists/alan-peppard/20110825-alan-peppard-bob-wilsonhailed-in-kera-documentary.ece). The Dallas Morning News. Retrieved 2013-01-25.

14. ^ Monty Python, v. American Broadcasting Companies, Inc., 538 F.2d 14 (2d Cir 1976)

(http://www.law.uconn.edu/homes/swilf/ip/cases/gilliam.htm)

15. ^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2cHoAoaVBz0

16. ^ "The 100 Best TV Shows of All-TIME"

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

14/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

(http://www.time.com/time/specials/2007/completelist/0,,1651341,00.html). TIME. 6 September 2007.

Retrieved 14 July 2009.

17. ^ "Channel 4s 50 Greatest Comedy Sketches"

(http://www.channel4.com/entertainment/tv/microsites/G/greatest/comedy_sketches/results.html).

Channel4.com. Retrieved 14 July 2009.

18. ^ "25 Top Cult Shows Ever!". TV Guide Magazine Group. 30 May 2004.

19. ^ TV Guide Names the Top Cult Shows Ever - Today's News: Our Take (http://www.tvguide.com/news/topcult-shows-40239.aspx) TV Guide: 29 June 2007

20. ^ "Douglas Adams - Biography - IMdb" (http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0010930/bio?

ref_=nm_dyk_qt_sm#quotes).

21. ^ "Lorne Michaels - Biography - IMDb" (http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0584427/bio?ref_=nm_ql_1).

22. ^ General Python FAQ (https://www.python.org/doc/faq/general/)

23. ^ "Weird but true"

(http://www.nypost.com/p/news/weird_but_true/weird_but_true_250UEa76btMUe1uqAswocM). New York

Post. January 28, 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

24. ^ Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. The British Look Abroad: Monty Python and the

Foreign. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

25. ^ Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. The British Look Abroad: Monty Python and the

Foreign. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

26. ^ Kern, Kevin F. (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. Twentieth-Century Vole, Mr. Neutron, and Spam:

Portrayals of American Culture in the Work of Monty Python. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

27. ^ Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. The British Look Abroad: Monty Python and the

Foreign. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

28. ^ Kern, Kevin F. (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. Twentieth-Century Vole, Mr. Neutron, and Spam:

Portrayals of American Culture in the Work of Monty Python. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

29. ^ Kern, Kevin F. (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. Twentieth-Century Vole, Mr. Neutron, and Spam:

Portrayals of American Culture in the Work of Monty Python. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

30. ^ Kern, Kevin F. (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. Twentieth-Century Vole, Mr. Neutron, and Spam:

Portrayals of American Culture in the Work of Monty Python. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

31. ^ Kern, Kevin F. (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. Twentieth-Century Vole, Mr. Neutron, and Spam:

Portrayals of American Culture in the Work of Monty Python. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

32. ^ Kern, Kevin F. (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. Twentieth-Century Vole, Mr. Neutron, and Spam:

Portrayals of American Culture in the Work of Monty Python. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

33. ^ Kern, Kevin F. (2014). Dobrogoszcz, Tomasz, ed. Twentieth-Century Vole, Mr. Neutron, and Spam:

Portrayals of American Culture in the Work of Monty Python. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

Bibliography

Landy, Marcia (2005). Monty Pythons Flying Circus. Wayne State University Press. ISBN08143-3103-3.

Larsen, Darl. Monty Python's Flying Circus: An Utterly Complete, Thoroughly Unillustrated,

Absolutely Unauthorized Guide to Possibly All the References From Arthur "Two Sheds" Jackson

to Zambesi. Lanham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, 2008. ISBN 0-8108-6131-3

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

15/16

2/25/2015

Monty Python's Flying Circus - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

External links

The Official Monty Python website

(http://www.pythonline.com)

Monty Pythons Flying Circus

Wikiquote has quotations

related to: Monty Python's

Flying Circus

(http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0063929/) at the Internet Movie Database

Museum of Broadcast Television

(http://www.museum.tv/archives/etv/M/htmlM/montypython/montypython.htm)

British Film Institute Screen Online (http://www.screenonline.org.uk/tv/id/469243/index.html)

"Monty Pythons Flying Circus"

(http://www.nostalgiacentral.com/television/comedy/montypython.htm) Nostalgia Central

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?

title=Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus&oldid=646688111"

Categories: 1969 British television programme debuts 1974 British television programme endings

1960s British television series 1970s British television series BBC television comedy

Black comedy television programs British television sketch shows

English-language television programming Monty Python Satirical television programmes

British satire Postmodernism

This page was last modified on 11 February 2015, at 19:31.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License; additional terms

may apply. By using this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. Wikipedia is a

registered trademark of the Wikimedia Foundation, Inc., a non-profit organization.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monty_Python%27s_Flying_Circus

16/16

You might also like

- Slapstick - WikipediaDocument8 pagesSlapstick - WikipediaalexcvsNo ratings yet

- The Making of Horror Movies: Key Figures who Established the GenreFrom EverandThe Making of Horror Movies: Key Figures who Established the GenreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Monty PythonDocument83 pagesMonty PythonLuisFrioNo ratings yet

- Monty Python Speaks: The Complete Oral History of Monty Python, as Told by the Founding Members and a Few of Their Many Friends and CollaboratorsFrom EverandMonty Python Speaks: The Complete Oral History of Monty Python, as Told by the Founding Members and a Few of Their Many Friends and CollaboratorsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (48)

- ThunderbirdsDocument23 pagesThunderbirdsMIDNITECAMPZ0% (1)

- Serial FilmDocument12 pagesSerial FilmjmmocaNo ratings yet

- SNL Vs IumorDocument4 pagesSNL Vs IumorGavri Nicusor0% (1)

- The Horror Guys Guide To The Horror Films of Peter Cushing: HorrorGuys.com Guides, #7From EverandThe Horror Guys Guide To The Horror Films of Peter Cushing: HorrorGuys.com Guides, #7No ratings yet

- Monty Python and Postmodern ThoughtDocument52 pagesMonty Python and Postmodern ThoughtMarloes Matthijssen100% (3)

- Navy Lark Series 12 BookletDocument17 pagesNavy Lark Series 12 Bookletfegged0% (1)

- Columbo TV SeriesDocument40 pagesColumbo TV Serieslordicon1No ratings yet

- Send in The Clones: Chaplin Imitators From Stage To Screen, From Circus To CartoonDocument6 pagesSend in The Clones: Chaplin Imitators From Stage To Screen, From Circus To CartoonAbhisek RoyBarmanNo ratings yet

- Reel History: The World According to the MoviesFrom EverandReel History: The World According to the MoviesRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- Weston-super-Mare Army World War I: Early Life and EducationDocument10 pagesWeston-super-Mare Army World War I: Early Life and EducationPhuong LeNo ratings yet

- R.burt - Unspeakable ShaXXXspearesDocument348 pagesR.burt - Unspeakable ShaXXXspearesCarlosNo ratings yet

- British Humour: Miu Stefania Raluca DianaDocument13 pagesBritish Humour: Miu Stefania Raluca DianaMiu NicoleNo ratings yet

- Rowan Sebastian AtkinsonDocument7 pagesRowan Sebastian AtkinsonargghhhhhhNo ratings yet

- The Horror Guys Guide to the Horror Films of Boris Karloff: HorrorGuys.com Guides, #9From EverandThe Horror Guys Guide to the Horror Films of Boris Karloff: HorrorGuys.com Guides, #9No ratings yet

- Fictional Character and Story: Thimble Theatre and Popeye Comic StripsDocument13 pagesFictional Character and Story: Thimble Theatre and Popeye Comic Stripspfd123456No ratings yet

- Biography of Charlie ChaplineDocument23 pagesBiography of Charlie Chaplineabhishek chauhanNo ratings yet

- Walking Distance: Remembering Classic Episodes from Classic TelevisionFrom EverandWalking Distance: Remembering Classic Episodes from Classic TelevisionNo ratings yet

- John CleeseDocument25 pagesJohn CleesecatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Navy Lark Series 13Document17 pagesNavy Lark Series 13feggedNo ratings yet

- Films From The Silent Era: History of The Non-Fiction Film, 2nd Revised Edition, New York: Oxford Univ. PressDocument10 pagesFilms From The Silent Era: History of The Non-Fiction Film, 2nd Revised Edition, New York: Oxford Univ. PressTimmy Singh KangNo ratings yet

- Top 10 Songs That Are Difficult To Sing at Karaoke & Auditions Part IIDocument9 pagesTop 10 Songs That Are Difficult To Sing at Karaoke & Auditions Part IIRioja Rio Peter-OpiaNo ratings yet

- The Adventures of Harry Lime - NotasDocument1 pageThe Adventures of Harry Lime - NotasPablo PerelNo ratings yet

- The Horror Guys Guide to The Horror Films of Vincent Price: HorrorGuys.com Guides, #5From EverandThe Horror Guys Guide to The Horror Films of Vincent Price: HorrorGuys.com Guides, #5No ratings yet

- Shakespeare Magazine 09Document48 pagesShakespeare Magazine 09Séverine Rubin100% (1)

- Movies and TV: The New York Public Library Book of AnswersFrom EverandMovies and TV: The New York Public Library Book of AnswersRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- 25 Best Historical Movies On Netflix For History BuffsDocument10 pages25 Best Historical Movies On Netflix For History BuffsZafar Habib ShaikhNo ratings yet

- 11 Facts About Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle's Super SleuthDocument12 pages11 Facts About Sherlock Holmes, Arthur Conan Doyle's Super SleuthMarija ĐokićNo ratings yet

- List of Monty Python's Flying Circus EpisodesDocument19 pagesList of Monty Python's Flying Circus Episodesvanveen1967No ratings yet

- Christopher Plummer - An Actor Should Be A MysteryDocument102 pagesChristopher Plummer - An Actor Should Be A MysteryChristopher Plummer100% (2)

- William ShatnerDocument1 pageWilliam ShatnerJames JacksonNo ratings yet

- Hollywood-NotesDocument1 pageHollywood-NotesAybukeNo ratings yet

- Order On Helpwriting - Net For Sapphire and Steel Assignment 5Document4 pagesOrder On Helpwriting - Net For Sapphire and Steel Assignment 5ewajwpccNo ratings yet

- Navy Lark Series 11 BookletDocument27 pagesNavy Lark Series 11 BookletfeggedNo ratings yet

- The Shawshank RedemptionDocument74 pagesThe Shawshank RedemptionБ. Наранчимэг100% (1)

- March 2015 CalendarDocument2 pagesMarch 2015 CalendarDrafthouseOneLoudounNo ratings yet

- TV Shows: What Television Program Did You See When You Were Child?Document5 pagesTV Shows: What Television Program Did You See When You Were Child?lucio enrique HernandeZNo ratings yet

- The Cinema-John EscottDocument29 pagesThe Cinema-John EscottAndres GuayesNo ratings yet

- ScriptDocument5 pagesScriptIssabelleNo ratings yet

- British Pioneers British FilmDocument10 pagesBritish Pioneers British FilmÁgnes AsztalosNo ratings yet

- Monty Python and The Holy Grail PDFDocument1 pageMonty Python and The Holy Grail PDFAlOlaveNo ratings yet

- Graham Chapman - 1 PDFDocument10 pagesGraham Chapman - 1 PDFAlOlaveNo ratings yet

- IncipitDocument5 pagesIncipitcatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- TonaryDocument20 pagesTonarycatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Musica Enchiriadis (En)Document2 pagesMusica Enchiriadis (En)catalinatorre0% (3)

- Fermat's Little TheoremDocument7 pagesFermat's Little TheoremcatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Appeal To MotiveDocument2 pagesAppeal To MotivecatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Fermat-Catalan ConjectureDocument3 pagesFermat-Catalan ConjecturecatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Fermat PointDocument7 pagesFermat Pointcatalinatorre0% (1)

- Fermat PseudoprimeDocument14 pagesFermat PseudoprimecatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Fermat QuotientDocument6 pagesFermat QuotientcatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Fermat PrizeDocument3 pagesFermat PrizecatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Fermat NumberDocument23 pagesFermat NumbercatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Theatre Royal, Drury LaneDocument19 pagesTheatre Royal, Drury LanecatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Director CircleDocument2 pagesDirector CirclecatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Fermat CubicDocument3 pagesFermat CubiccatalinatorreNo ratings yet

- Ben SdgeDocument1 pageBen SdgeCandy ValentineNo ratings yet

- SBI Current Account Form For Other Than Sole Proprietorship FirmDocument16 pagesSBI Current Account Form For Other Than Sole Proprietorship FirmKartik KumarNo ratings yet

- Burden of ProofDocument9 pagesBurden of ProofSNo ratings yet

- Reflection No. 1 - The Science and Study of Human Behavior by Emmalyn CarreonDocument3 pagesReflection No. 1 - The Science and Study of Human Behavior by Emmalyn CarreonEm Boquiren Carreon100% (1)

- The Flight To Intimacy - The Flight From IntimacyDocument5 pagesThe Flight To Intimacy - The Flight From IntimacyRatna Bhūṣaṇa Bhūṣaṇā Dāsa100% (2)

- Order Granting Preliminary Injunction - Drag Story Hour BanDocument53 pagesOrder Granting Preliminary Injunction - Drag Story Hour BanNBC MontanaNo ratings yet

- Key To Communication by Deaf Interpreter Services in UAEDocument3 pagesKey To Communication by Deaf Interpreter Services in UAEAmnah Tariq 2093018No ratings yet

- 208 S. Akard Street SUİTE 2954 Dallas Texas TX 75202 0800-288-2020Document1 page208 S. Akard Street SUİTE 2954 Dallas Texas TX 75202 0800-288-2020elise starkNo ratings yet

- Rules of Phonology 1Document21 pagesRules of Phonology 1aqilah atiqah100% (1)

- Case Study Accor HotelsDocument3 pagesCase Study Accor HotelsShishirThokal50% (2)

- 2nd UBIAN CONFERENCE 2023Document2 pages2nd UBIAN CONFERENCE 2023Rito KatoNo ratings yet

- Ce Laws, Ethics and Contracts - StudentDocument43 pagesCe Laws, Ethics and Contracts - StudentKherstine Muyano TantayNo ratings yet

- NaimisharanyamDocument11 pagesNaimisharanyammavericksailorNo ratings yet

- Foundations of Entrepreneurship: Module - 1Document29 pagesFoundations of Entrepreneurship: Module - 1Prathima GirishNo ratings yet

- Social Studies EssayDocument5 pagesSocial Studies Essayapi-315960690No ratings yet

- Spiritual FreedomDocument4 pagesSpiritual Freedomsophia48100% (2)

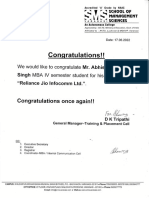

- Reliance Jio Infocomm Ltd. - ResultDocument1 pageReliance Jio Infocomm Ltd. - ResultRajesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Jovette L. Rafols: ExperiencesDocument4 pagesJovette L. Rafols: ExperiencesRazell RuizNo ratings yet

- Tibet Journal IndexDocument99 pagesTibet Journal Indexninfola100% (2)

- (16610) UmemeDocument1 page(16610) UmemeDAMBA GRAHAM ALEX100% (1)

- La Madre Esa de Las PizzasDocument25 pagesLa Madre Esa de Las PizzasAriel Alejandra MugiwaraNo ratings yet

- MarriageDocument15 pagesMarriageHimanshu SangtaniNo ratings yet

- Tax Invoice: Invoice Number G0057870 Invoice DateDocument1 pageTax Invoice: Invoice Number G0057870 Invoice DateshamNo ratings yet

- How Age Affects Survey Interaction - The Case of Intelligence StudiesDocument10 pagesHow Age Affects Survey Interaction - The Case of Intelligence StudiesJanlloyd DugoNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of Deposit ofDocument7 pagesAn Analysis of Deposit ofNisha Thapa0% (2)

- People vs. Hatani, 227 SCRA 497, November 08, 1993Document14 pagesPeople vs. Hatani, 227 SCRA 497, November 08, 1993Catherine DimailigNo ratings yet

- Bangladeshi Migration To West BengalDocument34 pagesBangladeshi Migration To West BengalAkshat KaulNo ratings yet

- Options Framework - Module 1 Black & White (Three Charts Per Page)Document16 pagesOptions Framework - Module 1 Black & White (Three Charts Per Page)RajNo ratings yet

- WebUser 451 2018 06 13 PDFDocument76 pagesWebUser 451 2018 06 13 PDFSlow HandNo ratings yet

- Asian RegionalismDocument40 pagesAsian RegionalismKent Salazar100% (1)

- Do Dead People Watch You Shower?: And Other Questions You've Been All but Dying to Ask a MediumFrom EverandDo Dead People Watch You Shower?: And Other Questions You've Been All but Dying to Ask a MediumRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (20)

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (39)

- The Season: Inside Palm Beach and America's Richest SocietyFrom EverandThe Season: Inside Palm Beach and America's Richest SocietyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- As You Wish: Inconceivable Tales from the Making of The Princess BrideFrom EverandAs You Wish: Inconceivable Tales from the Making of The Princess BrideRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1183)

- Alright, Alright, Alright: The Oral History of Richard Linklater's Dazed and ConfusedFrom EverandAlright, Alright, Alright: The Oral History of Richard Linklater's Dazed and ConfusedRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (23)

- Made-Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture under Late CapitalismFrom EverandMade-Up: A True Story of Beauty Culture under Late CapitalismRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- The Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust, Destroys Institutions, and Threatens Us All—But There Is a SolutionFrom EverandThe Canceling of the American Mind: Cancel Culture Undermines Trust, Destroys Institutions, and Threatens Us All—But There Is a SolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- Attack from Within: How Disinformation Is Sabotaging AmericaFrom EverandAttack from Within: How Disinformation Is Sabotaging AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- 1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtFrom Everand1963: The Year of the Revolution: How Youth Changed the World with Music, Fashion, and ArtRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5)

- Summary: The 50th Law: by 50 Cent and Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The 50th Law: by 50 Cent and Robert Greene: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Good Booty: Love and Sex, Black & White, Body and Soul in American MusicFrom EverandGood Booty: Love and Sex, Black & White, Body and Soul in American MusicRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (7)

- Greek Mythology: The Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes Handbook: From Aphrodite to Zeus, a Profile of Who's Who in Greek MythologyFrom EverandGreek Mythology: The Gods, Goddesses, and Heroes Handbook: From Aphrodite to Zeus, a Profile of Who's Who in Greek MythologyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (72)

- Don't Panic: Douglas Adams and the Hitchhiker's Guide to the GalaxyFrom EverandDon't Panic: Douglas Adams and the Hitchhiker's Guide to the GalaxyRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (488)

- Fear and Loathing at Rolling Stone: The Essential Writing of Hunter S. ThompsonFrom EverandFear and Loathing at Rolling Stone: The Essential Writing of Hunter S. ThompsonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (51)

- Dogland: Passion, Glory, and Lots of Slobber at the Westminster Dog ShowFrom EverandDogland: Passion, Glory, and Lots of Slobber at the Westminster Dog ShowNo ratings yet

- What Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of ComputingFrom EverandWhat Algorithms Want: Imagination in the Age of ComputingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (41)

- Psychedelic Buddhism: A User's Guide to Traditions, Symbols, and CeremoniesFrom EverandPsychedelic Buddhism: A User's Guide to Traditions, Symbols, and CeremoniesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Cynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms EverybodyFrom EverandCynical Theories: How Activist Scholarship Made Everything about Race, Gender, and Identity―and Why This Harms EverybodyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (221)

- Tomorrowland: Our Journey from Science Fiction to Science FactFrom EverandTomorrowland: Our Journey from Science Fiction to Science FactRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (49)

- The Psychedelic Explorer's Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred JourneysFrom EverandThe Psychedelic Explorer's Guide: Safe, Therapeutic, and Sacred JourneysRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (13)

- A Good Bad Boy: Luke Perry and How a Generation Grew UpFrom EverandA Good Bad Boy: Luke Perry and How a Generation Grew UpRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)