Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Dobb - Random Bigraphical Notes

Uploaded by

Camilo Fernández CarrozzaCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Dobb - Random Bigraphical Notes

Uploaded by

Camilo Fernández CarrozzaCopyright:

Available Formats

Cambridge Journal of Economics 1978, 2, 115-120

Random biographical notes

Maurice Dobb

Early education

Born in a suburb of N.W. London (24 July 1900) of a family of small business men

(father and grandfather had a draper's retail business; mother came of a decayed

Scottish-merchant's family, in poor financial circumstances). Ordinary religious (nonconformist-Presbyterian) and conservative upbringing (as a child read patriotic books,

e.g. about the Boer War, and once wept inconsolably for the death of General Gordon

in the Sudan). The family had little cultural background; but was sent to ordinary

middle class schools for educationand eventually to Charterhouse (an English public

school of the second rank). An unsuccessful schoolboy who showed no prowess at games

and little proficiency at classics (the main subject of his education). His academic

interest was only aroused when in his last year at school he was allowed to specialise in

History with the intention of taking a Scholarship Examination for Cambridge, studying

the subject under a talented master of liberal ideas and tendencies.

He would have joined the army on leaving school in December 1918 if the First

World War had lasted a month longer. As it was, he had three-quarters of a year

between leaving school and going up to Pembroke College, Cambridge, to which he

had obtained an Exhibition (but not a full Scholarship). It was in these nine months in

London as an ex-schoolboy that he made his first contacts with the Labour Movement,

with Socialism and with the ideas of the Russian Revolution (then just a year old); it

was also at this time that he first read Marx (with very limited understanding) and

other unorthodox writers such as J. A. Hobson, Bernard Shaw and William Morris.

It was at the same time that there was born in him the desire to study Economics

which he did (instead of History) on going to the University in October 1919.

First socialist contacts

The reasons for this early interest in socialist ideas (perhaps at first sight surprising

considering the environment) may be just worth mentioning. Probably it had its origin

in an increasing conflict in his last school-year with the more militarist-minded of his

schoolfellows whose only thoughts were of careers in the Army as officers, preferably in

some obsolete but snobbish branch like the Cavalry or Guards. Against them he

Downloaded from http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on December 16, 2014

These notes, written in 1965 for Tadeusz Kowalik, provide an apt introduction to this issue of the

Cambridge Journal of Economics which is dedicated to the memory of Maurice Dobb, for

they reveal the political commitment and humanity of a modest but essentially courageous man. The

essays which follow examine a variety of aspects of the wide range of Maurice Dobb's contributions

to economic knowledge. All display a spirit of constructive criticism which is appropriate in approaching the work of such a major figure.

116

M. H. Dobb

At the University, 1919-22

The result was that on going to Cambridge as a student he joined the University

Socialist Society within the first few days (its Secretary, whom he first approached to

join, was H. D. Dickinson, the future economist and author of The Economics ofSocialism).

Other members of the Socialist Society included J. D. Bernal (later Professor of Physics

and of Crystallography, University of London), Kingsley Martin (later editor of the

New Statesman), R. B. Braithwaite (to become a Professor of Philosophy at Cambridge),

and Allen Hutt (who was to be chief Typographer and sub-editor for the Daily Worker

over several decades). This society was fairly small and its discussions mainly theoretical

(a paper being read, followed by general discussion). In his second or third year at

Cambridge he assisted in forming (together with the son of the Labour Party leader

Arthur Henderson) the wider Cambridge University Labour Club which engaged in

more public activities, public meetings, etc., on the basis of the programme of the Labour

Party. He became Secretary of this Labour Club and later (in his final student year)

its Chairman (with Ewen Montagu, elder brother of Ivor Montagu, as secretary and

joint colleague).

In his first student year he also joined a local branch of a pacifist society called the

Union of Democratic Control; one of its first public meetings was broken up by angry

ex-servicemen students; this caused a clash with the authorities of his College, and he

himself narrowly escaped having his room wrecked by ex-officer-students of his own

College.

In either his 2nd or 3rd year as a student he helped in organising and addressing a

public meeting in London organised by the University Socialist Federation (a federation

of university socialist clubs or societies) in support of the so-called Triple Alliance strikemovement (a general strike of Miners, Railwaymen, Dockers and other transport

workers). As a result of this he (and also H. D. Dickinson) were invited to go for an

intensive three weeks of speaking and organising by the Unemployed Workers' Council

Downloaded from http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on December 16, 2014

championed the idea (without finding any support) of the need to know something of

politics in view of the coming problems of end-of-war and peace. He was much influenced

by an idealistic lecture at the school by Professor Gilbert Murray on the day the war

endedabout the need to ensure permanent peace and no-more-war. He got friendly

with an old servant at the school whom he found to be an early member of the British

Labour Party, and found him much more interesting to talk to than his schoolfellows.

As a result, on returning home to London he started to go to such Labour and Socialist

meetings as he saw advertised (it was the time of the 'Hands-off Russia' campaign,

which held monster meetings in the Albert Hall; also of heated discussions between

advocates of affiliation to the Second and the Third International). He bought left-wing

papers and pamphlets, and found a second-hand bookseller of left-wing sympathies who

advised him on books to read. He answered a poster advertising for helpers for the

Hampstead Labour Party in a local election; and from this worked for several months

as a volunteer with the Information Department of the Independent Labour Party

which was presided over by Emile Burns (later to be a foundation-member of the

British CP)also joined a local branch of the Independent Labour Party in a working

class district of London, where he made friends with young workers and actually spoke

on one occasion at a street-corner meeting. There were also some big strikes in this

post-war year of rapid inflation, and these moved him to passionate enthusiasm for the

strikers' cause (as well as to a romantic feeling that revolution was near).

Random biographical notes

117

Research Student at London School of Economics 1922-24

In his two years (1922-24) in London as a research student, he worked on the history

and theory of capitalist enterprise (nominally 'the Entrepreneur'). He wrote a thesis

(under the nominal supervision of Professor Edwin Carman) which won him a Ph.D.,

and which formed the basis for the rather unsuccessful book entitled Capitalist Enterprise

and Social Progress (published in 1925)an unsuccessful and jejune attempt to combine

the notion of surplus-value and exploitation with the theory of Marshall (but it contained some historical material about the origins of capitalism and the role of monopoly

and class-advantage which was to be developed 20 years later in his Studies in the

Development of Capitalism).

It was at the beginning of this two-year period in London that he joined the Communist Party, recently founded about a year previously; joining first an intellectuals'

branch called the West Central branch and then (on the dissolution of this branch)

transferring to a branch in the working class district of Camden Town in north London.

He did some speaking at this time to CP branches, workers' circles, etc., received some

experience of the eastern boroughs of London (Poplar, the dockland area etc.); and it

Downloaded from http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on December 16, 2014

movement in the so-called Black Country, north of Birmingham (a badly-depressed

iron and engineering and coal area). When By-Elections (for Parliament) took place

in Cambridge town, he spoke and canvassed for the Labour candidate (who at that

time was Hugh Dalton, an economist and later a Minister in Labour Governments).

In summer vacations he attended 'Summer Schools' organised by the Labour Research

Department (a left-wing organisation), which attracted both intellectuals and trade

unionists; here he came into contact with figures like G. D. H. Cole, Bernard Shaw,

Ellen Wilkinson, R. Page Arnot. In these various ways he acquired at this time some

practical experience of politics and of the working class movement. He also took part

in political debates in the Cambridge Union Society, a student club and debatingsociety, and for a short time also edited a student paper called Youth.

As regards his academic studies at Cambridge, he studied economics from the first,

without however abandoning his interest in history, especially economic history (including the history of capitalism and the history of trade unionism in Britain). At this

time he considered himself a Marxist and a supporter of the Soviet Revolution in

Russia; although at this time very little of the Marxist classics was available in English

apart from Marx's Capital, and Lenin's State and Revolutionfirstappeared in an English

translation about 1920. He had very little liking for Marshall, and only succeeded in

reading completely his Principles of Economics (essential at [that] time for examination

purposes) after the end of his 2nd year as a student of economics. On becoming a

member of Keynes's Political Economy Club (which met in Keynes's rooms in King's

College) in his 2nd or 3rd student-year, he read a paper at one of his first meetings on

Karl Marx (a paper approved of by Keyneswho liked unorthodoxy in the young, up to

a point). Among other writings, apart from Marx, that he can remember having

influenced him, were those of the Webbs and Labriola, Croce's essay on historical

materialism and the economics of Karl Marx, also for a time Georges Sorel (his Reflexions sur Violence), also Bertrand Russell, the philosopher, and the writings of the

Guild Socialists. He was successful in getting first class honours in both parts of the

Economics Tripos (an examination taken in two parts, one at the end of the 2nd year

of study, the other at the end of the 3rd and final year). On graduating he was able to

get a Studentship for Research at the London School of Economics.

118

M. H. Dobb

was at this time that he started to be active in the educational movement called the

Council of Labour Colleges, engaged in working class education of a Marxist tendenz

(he was for some years a committee member of its propaganda-organ, the Plebs League,

and for a short time edited its monthly magazine called Plebs, for which he wrote

frequently between 1923 and 1928). He also did work for the Labour Research Department (formerly the Fabian Research Dept).

Cambridge as a lecturer from 1924

The 1930s

From the early 1930s up to the war, with the rise of Fascism and the war danger, his

time and energies were increasingly occupied in political activity (mainly on a local

and regional basis) and polemical writing. This was also the time of the formation and

growth of the Communist Student Movement, and of a wave of interest among intellectuals in Marxism. Thus he organised a local (i.e. Cambridge) Anti-War Council

of Labour and trade union and pacifist organisations and became its Secretary (this was

inspired by the international movement and appeal of Henri Barbusse). One of its

achievements (apart from the holding of regional conferences covering the Eastern

Counties) was to organise a portable Anti-War Exhibition which later toured the

country; it was followed two years later by an Anti-Fascist Exhibition in which a number

of artists collaborated. In 1936 he was active in organising a regional Committee for

Downloaded from http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on December 16, 2014

He returned to Cambridge at the end of 1924 on being appointed as a Lecturer in

Economics in the Faculty of Economics and Politics (at that time a small and understaffed Faculty). In 1925 he paid his first visit to the Soviet Union, going in the company of Alexander Wicksteed, who had originally been a famine-relief worker in 1921

with the Quakers' Relief Mission in the famine districts of the lower Volga, and then

stayed on in Moscow as a teacher of English. While he was in Moscow he obtained

certain privileges as a visitor to the Bicentenary Celebrations of the Academy of Sciences

(to which Keynes was an official visitor), and he was present (along with the Swedish

E. Heckscher) at a meeting between Keynes and Gosplan economists (with Smilga

in the Chair, and Strumilin present inter alia) at which Keynes was presented with a

copy of the first 'Control Figures' which had just come from the printer.

This visit stimulated his interest in Soviet economy, and caused him to write a work

on the first ten years of Soviet economy which appeared in 1928 as Russian Economic

Development Since the Revolution. (As he could not at the time read Russian he had to work

with the assistance of H. C. Stevens as translator.) Both in 1929 and 1930 he was to

visit the S.U. again, travelling down the Volga from Nizhny (Gorki) to the lower Volga,

to Rostov, Novorossisk, Kharkhov for some weeks. These were the turbulent years of the

start of the First Five Year Plan; and on return to England he wrote several pamphlets

and lectured in various places about USSR.

Reverting to 1926 and the General Strike of that year. During the strike universityteaching virtually closed down, since all but a few students had gone off to strikebreak (i.e. work on railways, drive buses, etc.). As a result, he with a few other comrades

organised a publicity service for the strikers under the local Labour and Trades Council

(which acted as a local strike committee); and then when the Trade Union Congress

nationally started its own newspaper, The British Worker, organised its collection from

London and its regional distribution to the main towns of the Eastern Counties during

the General Strike.

Random biographical notes

119

Post-Second World War

At the end of the war and after (when academic duties were at a minimum owing to

the small number of students) he had an intensive period of academic study, the product

of which was two books, Studies in the Development of Capitalism (1946) and an enlargement

and extension of his earlier study of Soviet economy, Soviet Economic Development Since

1917(1948). In 1948 he was elected a Fellow and Lecturer ofTrinity College, Cambridge

(which entailed an increase in teaching-duties). At the same time he started collaborating

with P. SrafTa in completing the editing of the 10-volume edition of the Works and

Correspondence of David Ricardo and in writing several editorial Notes and Introductions

(including the Introduction to vol. I). In 1951 he visited India as Visiting Professor at

the University of Delhi School of Economics, and lectured extensively in Delhi, Aligarh,

Allahabad, Lucknow, Calcutta, Hyderabad and Bombay. From this dated his interest

in the problems of underdeveloped countries, and hence in the theory of growth and

development; which bore fruit in several articles on this subject (in Economie Appliquie

and Review of Economic Studies) and eventually in the theoretical booklet An Essay on

Downloaded from http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on December 16, 2014

aid to republican Spain, which among other things raised money to send a food ship

to Spain. About this time the Anti-War Council changed its name to the Cambridge

Peace Council, at the same time broadening its appeal to take in various religious bodies;

this organised marches and torchlight processions as well as meetings. Nationally he

was for some time a committee-member of the National Peace Council.

One result of this preoccupation in the 1930s with current political and polemical

work was a certain divorce from theoretical work and a partial separation from felloweconomists. He tended at this time to do the minimum (only) of his academic duties;

but, for example, took no part in the theoretical discussions among Cambridge economists at the time (discussions which both preceded and followed the publication of Keynes's

General Theory). From all this he stood apart. He did not lecture in the University at the

time on theoretical questions but mainly on 'applied' problems (e.g. a course on Social

Problems which included practical questions such as Labour Legislation, Social Insurance, Poverty Studies, Unemployment, Trade Unions and Wages). This followed on

his writing (in 1928) an elementary students' textbook on Wages for a textbook-series

(edited by Keynes) called the Cambridge Economic Handbooks. During this decade he

took part in the revived debate among economists about Mises's Wirtschaftsrechnung and

a socialist economy, but mainly in a polemical and perhaps (regarded in retrospect)

in a too negative manner. He also wrote his Political Economy and Capitalism (1937), partly

expository, partly polemical in intentioncriticising the Subjective Theory of Value and

seeking to explain and defend the Marxian approach in a manner understandable to

economic students trained in the Marshallian tradition. (The sub-title of the book was

Essays in Economic Traditiona reference to the tradition of Classical Political Economy

and of Marx as standing in that tradition.) But the book was too hurriedly written and

not based sufficiently deeply in theoretical thinking, so that much of it was superficial,

too-little constructive or matured from the standpoint of theoretical analysis (this is

most apparent probably in the chapter on Economic Crisessomewhat rewritten in

1940 under the influence of Kalecki's work and contact with Kalecki in Cambridge

and in the chapter on Economic Law in a Socialist Economy). As a result the book

fell between two stoolsto academic economists it seemed too polemical and negative

and remote from contemporary discussion; to many Marxists it seemed to make too

many concessions to Marshallian language and to have too-academic a form.

120

M. H. Dobb

t Maurice Dobb also received honorary degrees from the Universities of Budapest and Leicester. He was

a Fellow of die British Academy [eds].

Downloaded from http://cje.oxfordjournals.org/ at University of Nottingham on December 16, 2014

Economic Growth and Planning in 1960. In 1952 he attended the International Economic

Conference in Moscow as a member of the English delegation (of economists and business

men); and in 1956 he was a member of the party of English economists invited to

Poland by Polish economists. Here he was a witness of the 'Poznan events'from which

painful event perhaps came the first full realisation that contradictions were possible in

a socialist society. He participated actively in the intense discussions later in the year

in British communist and left-wing circles around the events in Hungary; and at the

1957 Congress of the British CP (to which he was a delegate from Cambridge) he

made a speech seconding an amendment to the main resolutionan amendment to

state that 'dogmatism' (in place of'revisionism') was the main danger to be combatted

(the amendment was defeated). He also supported some other minority resolutions and

amendments (in this reflecting the opinions of the branches on whose behalf he was a

delegate).

The Polish economists' discussion of 1956, which he had the opportunity of hearing,

revived his interest in the problems of pricing-policy in a socialist economy and the

need to experiment with more decentralised models. While still insistent on the value

and importance of planning for the 'macro-relations' of a socialist economy, he was

now convinced of the need to examine positively in the light of experience the role of

prices and of economic incentives. He proceeded to study in some detail current Soviet

discussions and experience of this, and wrote some articles about this (e.g. in Soviet

Studies and in Science and Society); some of his conclusions appeared in the final chapter

of his Essay on Economic Growth and Planning. He hopes in the future to devote a book to

a theoretical re-examination of this question, possibly linking it up with discussions

among bourgeois economists about 'welfare economics' and a 'welfare optimum'. (It

happened that at this time he was lecturing at the University on these subjects as part

of a course dealing with the general subject of 'Welfare Economics'; to which was to be

added from 1962 onwards a shorter course of lectures on 'The Planned Economies of

Eastern Europe'.)

In the second half of the '50s he was also engaged in discussions in Marxist circles

and journals (e.g. in the English journal Marxism Today) about the special features and

changes in post-war capitalismfollowing earlier historical discussion around his

Studies in the early '50s (e.g. the discussion with Sweezy, Takahashi etc., in Science and

Society of New York). On these subjects, historical and contemporary, he lectured

in the early '60s both in Bologna and in Rome (at the Gramsci Institute). He was a

member of the Editorial Board of Modern Quarterly and later of Marxism Today; also

for a time of the historical journal Past and Present.

In 1959 he was appointed a Reader in Economics (in English Universities a Reader

is a grade between Lecturer and a full Professor, and in Cambridge the post is created

ad hoc for individuals nominated by the Facultyat diis time other Readers in the

Faculty were Reddaway, Kaldor and Joan Robinson). In 1964 he was awarded an

honorary degree as Doctor of Economic Science at the Charles University of Prague in

a ceremony at the Karolinum.t He is due to retire from both his University and College

posts in 1967. He hopes after retirement to have time to write also a book on the history

of economic thought (about which he has lectured in the University for some 10 years

or more), concerned especially with the problem of ideology and apologetics in

Economic Theories at various times.

You might also like

- Eric Hobsbawm: Socialist Studies / Études Socialistes 8 (2) Autumn 2012Document11 pagesEric Hobsbawm: Socialist Studies / Études Socialistes 8 (2) Autumn 2012Roberto della SantaNo ratings yet

- Rowley - The Genesis of Red Brotherhood at WarDocument12 pagesRowley - The Genesis of Red Brotherhood at WarKim Anh Le ThiNo ratings yet

- Masaryk University in Brno Faculty of Arts: Reflections of British Society in The Campus NovelDocument37 pagesMasaryk University in Brno Faculty of Arts: Reflections of British Society in The Campus Novelzeeshanali1No ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 79.235.124.154 On Fri, 17 Jun 2022 15:41:36 UTCDocument20 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 79.235.124.154 On Fri, 17 Jun 2022 15:41:36 UTCJason KingNo ratings yet

- Raymond Williams BDocument4 pagesRaymond Williams BFar_away_21100% (1)

- Capitalism's Contradictions: Studies of Economic Thought Before and After MarxFrom EverandCapitalism's Contradictions: Studies of Economic Thought Before and After MarxRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Towards A Libertarian Socialism: Reflections on the British Labour Party and European Working-Class MovementsFrom EverandTowards A Libertarian Socialism: Reflections on the British Labour Party and European Working-Class MovementsNo ratings yet

- 11 Pioneers of Soc SciDocument5 pages11 Pioneers of Soc SciMillan YsabelleNo ratings yet

- Maurice Dobb - WikipediaDocument1 pageMaurice Dobb - WikipediaBruno Miller TheodosioNo ratings yet

- Al Richardson, Introduction To C.L.R. James, World Revolution 1917-1936. The Rise and Fall of The Communist InternationalDocument12 pagesAl Richardson, Introduction To C.L.R. James, World Revolution 1917-1936. The Rise and Fall of The Communist InternationaldanielgaidNo ratings yet

- The Marxist Aesthetics of Christopher CaudwellDocument22 pagesThe Marxist Aesthetics of Christopher CaudwellGiannis PardalisNo ratings yet

- Eric HobsbawmDocument10 pagesEric HobsbawmMarios DarvirasNo ratings yet

- Stuart Hall: LIFE AND TIMES OF THE FIRST NEW LEFTDocument20 pagesStuart Hall: LIFE AND TIMES OF THE FIRST NEW LEFTTigersEye99No ratings yet

- Tribute to Historian Eric Hobsbawm and His Remarkable Life and WorkDocument2 pagesTribute to Historian Eric Hobsbawm and His Remarkable Life and Worknagendrar_2No ratings yet

- Isaac DeutscherDocument5 pagesIsaac DeutscherMarios DarvirasNo ratings yet

- Essays in Ancient and Modern HistoriographyFrom EverandEssays in Ancient and Modern HistoriographyRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Ricardian Socialists I Smithian Socialists: What's in A Name?Document29 pagesRicardian Socialists I Smithian Socialists: What's in A Name?J.M.G.No ratings yet

- Lenin Imperialism CritDocument18 pagesLenin Imperialism Critchris56aNo ratings yet

- MacDiarmid & PoundDocument15 pagesMacDiarmid & PoundGordon LoganNo ratings yet

- Solidarity without Borders: Gramscian Perspectives on Migration and Civil Society AlliancesFrom EverandSolidarity without Borders: Gramscian Perspectives on Migration and Civil Society AlliancesNo ratings yet

- Prophet of Community: The Romantic Socialism of Gustav LandauerFrom EverandProphet of Community: The Romantic Socialism of Gustav LandauerRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Economics As A ScienceDocument11 pagesEconomics As A ScienceTeacher anaNo ratings yet

- Lohia As A Doctoral Student in Berli1Document6 pagesLohia As A Doctoral Student in Berli1Mahesh ChickmathNo ratings yet

- Eduard Bernstein The Preconditions of Socialism 1897 1899Document265 pagesEduard Bernstein The Preconditions of Socialism 1897 1899EscarroNo ratings yet

- Davis Et Al, Cultural Studies NowDocument20 pagesDavis Et Al, Cultural Studies NowMark TrentonNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx on Society and Social Change: With Selections by Friedrich EngelsFrom EverandKarl Marx on Society and Social Change: With Selections by Friedrich EngelsNo ratings yet

- 59IJELS 110202044 Doris PDFDocument6 pages59IJELS 110202044 Doris PDFIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- Review: African Americans, Culture and Communism: - Alan WaldDocument22 pagesReview: African Americans, Culture and Communism: - Alan WaldRafael CostaNo ratings yet

- Herbert Butterfield: History, Providence, and Skeptical PoliticsFrom EverandHerbert Butterfield: History, Providence, and Skeptical PoliticsNo ratings yet

- David Montgomery Marxism and Utopianism in The USADocument6 pagesDavid Montgomery Marxism and Utopianism in The USAMaurizio AcerboNo ratings yet

- Subalternity, Antagonism, Autonomy: Constructing the Political SubjectFrom EverandSubalternity, Antagonism, Autonomy: Constructing the Political SubjectNo ratings yet

- 2 - Gildea2017Document27 pages2 - Gildea2017RolandoNo ratings yet

- Werner Sombart's The Jews and Modern CapitalismDocument28 pagesWerner Sombart's The Jews and Modern CapitalismFauzan RasipNo ratings yet

- Da 1998Document17 pagesDa 1998Paul DumitruNo ratings yet

- Study Guide to Darkness at Noon and The Age of Longing by Arthur KoestlerFrom EverandStudy Guide to Darkness at Noon and The Age of Longing by Arthur KoestlerNo ratings yet

- Raymond William's Modern Tragedy (A Critical Analysis by Qaisar Iqbal Janjua)Document20 pagesRaymond William's Modern Tragedy (A Critical Analysis by Qaisar Iqbal Janjua)Qaisar Iqbal Janjua75% (28)

- (Anthologies of English Literature) Eric Homberger (Auth.) - American Writers and Radical Politics, 1900-39 - Equivocal Commitments-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1986)Document281 pages(Anthologies of English Literature) Eric Homberger (Auth.) - American Writers and Radical Politics, 1900-39 - Equivocal Commitments-Palgrave Macmillan UK (1986)Bbp HosmilloNo ratings yet

- 一个社会主义的预言家Document9 pages一个社会主义的预言家黎华楠No ratings yet

- FulltextDocument93 pagesFulltextKiranNo ratings yet

- Method/TheoryDocument2 pagesMethod/TheoryDanielRamirezNo ratings yet

- Peter Drucker A Functioning Society Selections From Sixty-Five Years of Writing On Community, Society, and Polity 2002Document267 pagesPeter Drucker A Functioning Society Selections From Sixty-Five Years of Writing On Community, Society, and Polity 2002emilvulcu100% (2)

- Lukács Analysis of Fascism's Social Base and IdeologyDocument13 pagesLukács Analysis of Fascism's Social Base and IdeologyTijana OkićNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx's Early Life and Education: New YorkDocument8 pagesKarl Marx's Early Life and Education: New YorkMuhammad Arslan AkramNo ratings yet

- What Is Meant by Charles Beards ThesisDocument4 pagesWhat Is Meant by Charles Beards Thesisjenniferlettermanspringfield100% (2)

- Shapiro LifeDocument11 pagesShapiro Lifechapman99No ratings yet

- Gramsci on Tahrir: Revolution and Counter-Revolution in EgyptFrom EverandGramsci on Tahrir: Revolution and Counter-Revolution in EgyptNo ratings yet

- Butterfield and International RelationsDocument19 pagesButterfield and International RelationsMatheus FernandesNo ratings yet

- American Literature Between The Wars 1914 - 1945Document4 pagesAmerican Literature Between The Wars 1914 - 1945cultural_mobilityNo ratings yet

- Historical Materialism 24.1 (2016)Document236 pagesHistorical Materialism 24.1 (2016)Txavo HesiarenNo ratings yet

- Communism and McCarthyism in Cold War New YorkDocument2 pagesCommunism and McCarthyism in Cold War New Yorkspyros barrett100% (1)

- E.P. Thompson and the Radical Roots of RomanticismDocument5 pagesE.P. Thompson and the Radical Roots of RomanticismyucaiNo ratings yet

- Why Has Marxism Had Only Limited Influence in BritainDocument6 pagesWhy Has Marxism Had Only Limited Influence in BritainloicocoNo ratings yet

- Against the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas - Second EditionFrom EverandAgainst the Current: Essays in the History of Ideas - Second EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (33)

- Gregory Claeys - Early Socialism As Intellectual HistoryDocument13 pagesGregory Claeys - Early Socialism As Intellectual HistoryCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Claeys - The Only Man of Nature That Ever Appeared in The WorldDocument25 pagesClaeys - The Only Man of Nature That Ever Appeared in The WorldCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Two Years of Popular Unity in Chile: A Concise AssessmentDocument23 pagesTwo Years of Popular Unity in Chile: A Concise AssessmentCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Falabella - Labour in Chile Under The Junta 1973-1979Document68 pagesFalabella - Labour in Chile Under The Junta 1973-1979Camilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Yugoslavian Socialist ExperienceDocument20 pagesYugoslavian Socialist ExperienceCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Cien Anos de Controversia en La Antropologia AnglosajonaDocument24 pagesCien Anos de Controversia en La Antropologia AnglosajonaArqElvyAColladoNo ratings yet

- Hutton - Intellectual History and The History of PhilosophyDocument14 pagesHutton - Intellectual History and The History of PhilosophyCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Ball - From Core To Sore ConceptsDocument7 pagesBall - From Core To Sore ConceptsCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Review - The Chilean Road To Socialism RevisitedDocument30 pagesReview - The Chilean Road To Socialism RevisitedCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Harris - Marxism and The Transition To Socialism in Latin AmericaDocument48 pagesHarris - Marxism and The Transition To Socialism in Latin AmericaCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- C. Pateman - Criticising Empirical Thoerists of DemocracyDocument5 pagesC. Pateman - Criticising Empirical Thoerists of DemocracypopolovskyNo ratings yet

- Beer and RevolutionDocument287 pagesBeer and Revolutiondjs123No ratings yet

- Schlesinger - The CPSU ProgrammeDocument19 pagesSchlesinger - The CPSU ProgrammeCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- David R. Corkill - The Chilean Socialist Party and The Popular Front 1933-41Document14 pagesDavid R. Corkill - The Chilean Socialist Party and The Popular Front 1933-41Camilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Joyce - What Is The Social in Social HistoryDocument36 pagesJoyce - What Is The Social in Social HistoryCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Suter - A Thorn in The Side of Social History Jacques RanciereDocument26 pagesSuter - A Thorn in The Side of Social History Jacques RanciereCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- The Crisis of Chile's Socialist Party in 1979Document32 pagesThe Crisis of Chile's Socialist Party in 1979Camilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Labour History, the 'Linguistic Turn' and Postmodernism: An Autobiographical ReflectionDocument19 pagesLabour History, the 'Linguistic Turn' and Postmodernism: An Autobiographical ReflectionCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Laclau - Socialism, The People, Democracy The Transformation of Hegemonic LogicDocument6 pagesLaclau - Socialism, The People, Democracy The Transformation of Hegemonic LogicCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Bhikhu Parekh - The Political Philosophy of Michael OakeshottDocument27 pagesBhikhu Parekh - The Political Philosophy of Michael OakeshottCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Jack Ray Thomas - The Evolution of Chilean Socialist Marmaduke GroveDocument17 pagesJack Ray Thomas - The Evolution of Chilean Socialist Marmaduke GroveCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Notes On Deconstructing The Popular - Stuart HallDocument12 pagesNotes On Deconstructing The Popular - Stuart HallBlake Huggins80% (5)

- Social or Political CleavagesDocument13 pagesSocial or Political CleavagesCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Wiener - Quentin Skinner S HobbesDocument11 pagesWiener - Quentin Skinner S HobbesCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Schlesinger - The CPSU ProgrammeDocument19 pagesSchlesinger - The CPSU ProgrammeCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Althusser - How To Read Marx's CapitalDocument5 pagesAlthusser - How To Read Marx's CapitalCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Walter L. Adamson - Towards The Prison NotebooksDocument28 pagesWalter L. Adamson - Towards The Prison NotebooksCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- David R. Corkill - The Chilean Socialist Party and The Popular Front 1933-41Document14 pagesDavid R. Corkill - The Chilean Socialist Party and The Popular Front 1933-41Camilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Labour History, the 'Linguistic Turn' and Postmodernism: An Autobiographical ReflectionDocument19 pagesLabour History, the 'Linguistic Turn' and Postmodernism: An Autobiographical ReflectionCamilo Fernández CarrozzaNo ratings yet

- Egor 1-1Document7 pagesEgor 1-1rolandebere24No ratings yet

- English LanguageDocument4 pagesEnglish LanguageHamizah Ab KarimNo ratings yet

- The College of New Jersey Hosts Its First New Jersey Model United Nations ConferenceDocument16 pagesThe College of New Jersey Hosts Its First New Jersey Model United Nations ConferenceHenggao CaiNo ratings yet

- Worksheet 6: Isn't Aren'tDocument2 pagesWorksheet 6: Isn't Aren'tAnonymous J89cuC7cGNo ratings yet

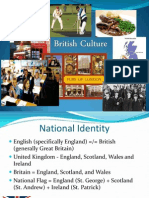

- British CultureDocument15 pagesBritish CultureDavid Jacob Donoso Leiva100% (2)

- Cel Week4Document4 pagesCel Week4fatin amirah0% (1)

- College of Technology: City of Malabon UniversityDocument3 pagesCollege of Technology: City of Malabon UniversityMary Grace Baston OribelloNo ratings yet

- Weebly Guided Reading Miryam KashanianDocument11 pagesWeebly Guided Reading Miryam Kashanianapi-274278464No ratings yet

- Letter of IntentDocument1 pageLetter of Intentnorhamina.aliNo ratings yet

- Training Proposal Ces Slac Sessions.2019.2020Document2 pagesTraining Proposal Ces Slac Sessions.2019.2020Jemima joy antonio93% (15)

- Activity Completion Report: Doña Candelaria Meneses-Duque National High SchoolDocument4 pagesActivity Completion Report: Doña Candelaria Meneses-Duque National High SchoolAlex TristeNo ratings yet

- BARACBAC Community School TLE LessonDocument3 pagesBARACBAC Community School TLE LessonMaRosary Amor L. EstradaNo ratings yet

- Devi Ahilya Vishwavidyalaya, IndoreDocument30 pagesDevi Ahilya Vishwavidyalaya, IndoremohanNo ratings yet

- Principles of Curriculum OrganizationDocument14 pagesPrinciples of Curriculum OrganizationDaniyal Jatoi86% (28)

- 8607 - Observation ReportsDocument7 pages8607 - Observation ReportsAmyna Rafy AwanNo ratings yet

- IEB (Institution of Engineers, Bangladesh) Membership FormDocument4 pagesIEB (Institution of Engineers, Bangladesh) Membership Formtowfiqeee100% (1)

- Find Credit Score Using Customer Bank BalancesDocument75 pagesFind Credit Score Using Customer Bank Balancesshubham kumarNo ratings yet

- CLIL NI 2 Unit 3 HistoryDocument3 pagesCLIL NI 2 Unit 3 HistoryJavier Vicente GuevaraNo ratings yet

- DLL Mathematics 4 q1 w2Document2 pagesDLL Mathematics 4 q1 w2ricky gomez jrNo ratings yet

- Broward SoftballDocument1 pageBroward SoftballMiami HeraldNo ratings yet

- June 2008 Rural Women Magazine, New ZealandDocument8 pagesJune 2008 Rural Women Magazine, New ZealandRural Women New ZealandNo ratings yet

- Episode 1 The School EnvironmentDocument11 pagesEpisode 1 The School Environmentpengeng tulog100% (5)

- 1 Bus ServiceDocument1 page1 Bus Serviceapi-294216460No ratings yet

- Government College JobDocument15 pagesGovernment College JobRugved ThakareNo ratings yet

- Annotated Literature ReviewDocument60 pagesAnnotated Literature Reviewapi-447630452No ratings yet

- Jmannheim Resume WeeblyDocument2 pagesJmannheim Resume Weeblyapi-356576012No ratings yet

- Brown Moot CourtDocument20 pagesBrown Moot CourtDanyal AhmedNo ratings yet

- M Tech Result 2016Document33 pagesM Tech Result 2016Hemanta DikshitNo ratings yet

- Learner'S Needs, Progress and Achievement Cardex: Kalalake Elementary SchoolDocument1 pageLearner'S Needs, Progress and Achievement Cardex: Kalalake Elementary SchoolElizabeth Cinco Sto DomingoNo ratings yet

- Institution Profile PageDocument3 pagesInstitution Profile Pageapi-280155568No ratings yet