Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Maurice Merleau Ponty

Uploaded by

kenadia11Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Maurice Merleau Ponty

Uploaded by

kenadia11Copyright:

Available Formats

Maurice Merleau-Ponty

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (French: [mis mlop ti];

14 March 1908 3 May 1961) was a French

phenomenological philosopher, strongly inuenced by

Edmund Husserl and Martin Heidegger. The constitution of meaning in human experience was his main interest and he wrote on perception, art and politics. He was

on the editorial board of Les Temps modernes, the leftist

magazine created by Jean-Paul Sartre in 1945.

At the core of Merleau-Pontys philosophy is a sustained

argument for the foundational role perception plays in

understanding the world as well as engaging with the

world. Like the other major phenomenologists, MerleauPonty expressed his philosophical insights in writings on

art, literature, linguistics, and politics. He was the only

major phenomenologist of the rst half of the twentieth century to engage extensively with the sciences and

especially with descriptive psychology. It is through

this engagement that his writings have become inuential in the recent project of naturalizing phenomenology,

in which phenomenologists use the results of psychology

and cognitive science.

Merleau-Ponty emphasized the body as the primary site

of knowing the world, a corrective to the long philosophical tradition of placing consciousness as the source of

knowledge, and maintained that the body and that which

it perceived could not be disentangled from each other.

The articulation of the primacy of embodiment led him

away from phenomenology towards what he was to call

indirect ontology or the ontology of the esh of the

world (la chair du monde), seen in his last incomplete

work, The Visible and Invisible, and his last published essay, Eye and Mind.

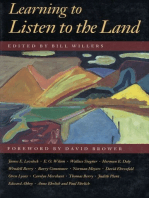

Merleau-Pontys grave at Pre Lachaise Cemetery in Paris, where

he was buried with his mother Louise and his wife Suzanne

in 1935 became a tutor at the cole Normale Suprieure,

where he was awarded his doctorate on the basis of two

important books: La structure du comportement (1942)

and Phnomnologie de la Perception (1945).

After teaching at the University of Lyon from 1945 to

1948, Merleau-Ponty lectured on child psychology and

education at the Sorbonne from 1949 to 1952.[11] He

was awarded the Chair of Philosophy at the Collge de

1 Life

France from 1952 until his death in 1961, making him

Merleau-Ponty was born in 1908 in Rochefort-sur-Mer, the youngest person to have been elected to a Chair.

Charente-Maritime, France. His father died in 1913 Besides his teaching, Merleau-Ponty was also politiwhen Merleau-Ponty was ve years old.[10] After sec- cal editor for Les Temps modernes from the founding

ondary schooling at the lyce Louis-le-Grand in Paris, of the journal in October 1945 until December 1952.

Maurice Merleau-Ponty became a student at the cole In his youth he had read Karl Marx's writings[12] and

Normale Suprieure, where he studied alongside Jean- Sartre even claimed that Merleau-Ponty converted him

Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, and Simone Weil. He to Marxism.[13] Their friendship ended over a quarrel as

passed the agrgation in philosophy in 1930.

he became disillusioned about communism, while Sartre

Merleau-Ponty taught rst at the Lyce de Beauvais still endorsed it.

(193133) and then got a fellowship to do research from Merleau-Ponty died suddenly of a stroke in 1961 at age

the Caisse Nationale de la Recherche Scientique. From 53, apparently while preparing for a class on Descartes.

19341935 he taught at the Lyce de Chartres. He then He is buried in Pre Lachaise Cemetery in Paris.

1

2

2.1

2 THOUGHT

Thought

we encounter meaningful things in a unied though ever

open-ended world.

Consciousness

2.2 The primacy of perception

In his Phenomenology of Perception (rst published in

French in 1945), Merleau-Ponty developed the concept

of the body-subject as an alternative to the Cartesian

cogito. This distinction is especially important in that

Merleau-Ponty perceives the essences of the world existentially. Consciousness, the world, and the human body

as a perceiving thing are intricately intertwined and mutually engaged. The phenomenal thing is not the unchanging object of the natural sciences, but a correlate

of our body and its sensory-motor functions. Taking

up and communing with (Merleau-Pontys phrase) the

sensible qualities it encounters, the body as incarnated

subjectivity intentionally elaborates things within an everpresent world frame, through use of its pre-conscious,

prepredicative understanding of the worlds makeup. The

elaboration, however, is inexhaustible (the hallmark of

any perception according to Merleau-Ponty). Things are

that upon which our body has a grip (prise), while the

grip itself is a function of our connaturality with the

worlds things. The world and the sense of self are emergent phenomena in an ongoing becoming.

The essential partiality of our view of things, their being given only in a certain perspective and at a certain

moment in time does not diminish their reality, but on

the contrary establishes it, as there is no other way for

things to be copresent with us and with other things than

through such "Abschattungen" (sketches, faint outlines,

adumbrations). The thing transcends our view, but is

manifest precisely by presenting itself to a range of possible views. The object of perception is immanently tied

to its backgroundto the nexus of meaningful relations

among objects within the world. Because the object is inextricably within the world of meaningful relations, each

object reects the other (much in the style of Leibnizs

monads). Through involvement in the world being-inthe-world the perceiver tacitly experiences all the perspectives upon that object coming from all the surrounding things of its environment, as well as the potential perspectives that that object has upon the beings around it.

Each object is a mirror of all others. Our perception of

the object through all perspectives is not that of a propositional, or clearly delineated, perception. Rather, it is

an ambiguous perception founded upon the bodys primordial involvement and understanding of the world and

of the meanings that constitute the landscapes perceptual gestalt. Only after we have been integrated within

the environment so as to perceive objects as such can we

turn our attention toward particular objects within the

landscape so as to dene them more clearly. (This attention, however, does not operate by clarifying what is

already seen, but by constructing a new gestalt oriented

toward a particular object.) Because our bodily involvement with things is always provisional and indeterminate,

From the time of writing Structure of Behavior and

Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty wanted to

show, in opposition to the idea that drove the tradition

beginning with John Locke, that perception was not the

causal product of atomic sensations. This atomist-causal

conception was being perpetuated in certain psychological currents of the time, particularly in behaviourism.

According to Merleau-Ponty, perception has an active

dimension, in that it is a primordial openness to the

lifeworld (to the "Lebenswelt").

This primordial openness is at the heart of his thesis of the

primacy of perception. The slogan of the phenomenology of Edmund Husserl is all consciousness is consciousness of something, which implies a distinction between

acts of thought (the noesis) and intentional objects of

thought (the noema). Thus, the correlation between noesis and noema becomes the rst step in the constitution of

analyses of consciousness.

However, in studying the posthumous manuscripts

of Husserl, who remained one of his major inuences, Merleau-Ponty remarked that, in their evolution,

Husserls work brings to light phenomena which are not

assimilable to noesisnoema correlation. This is particularly the case when one attends to the phenomena of the

body (which is at once body-subject and body-object),

subjective time (the consciousness of time is neither an

act of consciousness nor an object of thought) and the

other (the rst considerations of the other in Husserl led

to solipsism).

The distinction between acts of thought (noesis) and

"intentional objects of thought (noema) does not seem,

therefore, to constitute an irreducible ground. It appears

rather at a higher level of analysis. Thus, Merleau-Ponty

does not postulate that all consciousness is consciousness of something, which supposes at the outset a noeticnoematic ground. Instead, he develops the thesis according to which all consciousness is perceptual consciousness. In doing so, he establishes a signicant turn in the

development of phenomenology, indicating that its conceptualisations should be re-examined in the light of the

primacy of perception, in weighing up the philosophical

consequences of this thesis.

2.3 Corporeity

Taking the study of perception as his point of departure,

Merleau-Ponty was led to recognize that ones own body

(le corps propre) is not only a thing, a potential object of

study for science, but is also a permanent condition of

experience, a constituent of the perceptual openness to

2.4

Language

3

transcend the organic level of the body, such as in intellectual operations and the products of ones cultural life.

Ren Descartes

the world. He therefore underlines the fact that there is

an inherence of consciousness and of the body of which

the analysis of perception should take account. The primacy of perception signies a primacy of experience, so Ferdinand de Saussure

to speak, insofar as perception becomes an active and

constitutive dimension.

Merleau-Ponty demonstrates a corporeity of consciousness as much as an intentionality of the body, and so

stands in contrast with the dualist ontology of mind and

body in Ren Descartes, a philosopher to whom MerleauPonty continually returned, despite the important dierences that separate them. In the Phenomenology of Perception Merleau-Ponty wrote: Insofar as I have hands,

feet; a body, I sustain around me intentions which are

not dependent on my decisions and which aect my surroundings in a way that I do not choose (1962, p. 440).

The question concerning corporeity connects also with

Merleau-Pontys reections on space (l'espace) and the

primacy of the dimension of depth (la profondeur) as implied in the notion of being in the world (tre au monde;

to echo Heidegger's In-der-Welt-sein) and of ones own

body (le corps propre).[14]

2.4

Language

The highlighting of the fact that corporeity intrinsically

has a dimension of expressivity which proves to be fundamental to the constitution of the ego is one of the conclusions of The Structure of Behavior that is constantly

reiterated in Merleau-Pontys later works. Following this

theme of expressivity, he goes on to examine how an incarnate subject is in a position to undertake actions that

He carefully considers language, then, as the core of

culture, by examining in particular the connections between the unfolding of thought and sense enriching his

perspective not only by an analysis of the acquisition of

language and the expressivity of the body, but also by taking into account pathologies of language, painting, cinema, literature, poetry and song.

This work deals mainly with language, beginning with the

reection on artistic expression in The Structure of Behavior which contains a passage on El Greco (p. 203)

that pregures the remarks that he develops in Czannes

Doubt (1945) and follows the discussion in Phenomenology of Perception. The work, undertaken while serving as

the Chair of Child Psychology and Pedagogy at the University of the Sorbonne, is not a departure from his philosophical and phenomenological works, but rather an important continuation in the development of his thought.

As the course outlines of his Sorbonne lectures indicate, during this period he continues a dialogue between phenomenology and the diverse work carried out

in psychology, all in order to return to the study of the

acquisition of language in children, as well as to broadly

take advantage of the contribution of Ferdinand de Saussure to linguistics, and to work on the notion of structure

through a discussion of work in psychology, linguistics

and social anthropology.

2.5

4 INFLUENCE

Art

The attention Merleau-Ponty pays to diverse forms of art

(visual, plastic, literary, poetic, etc.) should not be attributed to a concern with beauty per se. Nor is his work

an attempt to elaborate normative criteria for art. Thus,

one does not nd in his work a theoretical attempt to discern what constitutes a major work or a work of art, or

even handicraft.

While he does not establish any normative criteria for

art as such, there is nonetheless in his work a prevalent distinction between primary and secondary modes

of expression. This distinction appears in Phenomenology of Perception (p. 207, 2nd note [Fr. ed.]) and is

sometimes repeated in terms of spoken and speaking language (le langage parl et le langage parlant) (The Prose

of the World, p. 10). Spoken language (le langage parl), or secondary expression, returns to our linguistic baggage, to the cultural heritage that we have acquired, as

well as the brute mass of relationships between signs and

signications. Speaking language (le langage parlant), or

primary expression, such as it is, is language in the production of a sense, language at the advent of a thought, at

the moment where it makes itself an advent of sense.

which also implies taking into consideration the dimensions of historicity and intersubjectivity. (However, Merleau-Pontys reading of Malraux has been questioned in a recent major study of Malrauxs theory of

art which argues that Merleau-Ponty seriously misunderstood Malraux.)[16] For Merleau-Ponty, style is born

of the interaction between two or more elds of being.

Rather than being exclusive to individual human consciousness, consciousness is born of the pre-conscious

style of the world, of Nature.

2.6 Science

In his essay Czannes Doubt, in which he identies

Czannes impressionistic theory of painting as analogous to his own concept of radical reection, the attempt to return to, and reect on, prereective consciousness, Merleau-Ponty identies science as the opposite of

art. In Merleau-Pontys account, whereas art is an attempt to capture an individuals perception, science is

anti-individualistic. In the preface to his Phenomenology

of Perception, Merleau-Ponty presents a phenomenological objection to positivism: that it can tell us nothing

about human subjectivity. All that a scientic text can

explain is the particular individual experience of that sciIt is speaking language, that is to say, primary expres- entist, which cannot be transcended. For Merleau-Ponty,

sion, that interests Merleau-Ponty and which keeps his science neglects the depth and profundity of the phenomattention through his treatment of the nature of produc- ena that it endeavors to explain.

tion and the reception of expressions, a subject which also

Merleau-Ponty understood science to be an ex post facto

overlaps with an analysis of action, of intentionality, of

abstraction. Causal and physiological accounts of perperception, as well as the links between freedom and exception, for example, explain perception in terms that are

ternal conditions.

only arrived at after abstracting from the phenomenon itThe notion of style occupies an important place in In- self. Merleau-Ponty chastised science for taking itself to

direct Language and the Voices of Silence. In spite of be the area in which a complete account of nature may

certain similarities with Andr Malraux, Merleau-Ponty be given. The subjective depth of phenomena cannot

distinguishes himself from Malraux in respect to three be given in science as it is. This characterizes Merleauconceptions of style, the last of which is employed in Pontys attempt to ground science in phenomenological

Malrauxs The Voices of Silence. Merleau-Ponty remarks objectivity and, in essence, institute a return to the phethat in this work style is sometimes used by Malraux nomena.

in a highly subjective sense, understood as a projection

of the artists individuality. Sometimes it is used, on

the contrary, in a very metaphysical sense (in Merleau3 Did Merleau-Ponty write a

Pontys opinion, a mystical sense), in which style is conNovel?

nected with a conception of an "ber-artist expressing

the Spirit of Painting. Finally, it sometimes is reduced

to simply designating a categorization of an artistic school An article published in French newspaper Le Monde

or movement. (However, this account of Malrauxs no- in October 2014 makes the case of recent discovertion of stylea key element in his thinkingis very ies about Merleau-Pontys likely authorship of the novel

questionable.[15] )

Nord. Rcit de l'actique (Grasset, 1928). Convergent

For Merleau-Ponty, it is these uses of the notion of sources from close friends (Simone de Beauvoir, Elisastyle that lead Malraux to postulate a cleavage be- beth Lacoin) seem to leave little doubt about the fact that

tween the objectivity of Italian Renaissance painting behind the pseudonym Jacques Heller, it is the 20-year

[17]

and the subjectivity of painting in his own time, a old Merleau-Ponty who is hiding.

conclusion that Merleau-Ponty disputes. According to

Merleau-Ponty, it is important to consider the heart

of this problematic, by recognizing that style is rst 4 Inuence

of all a demand owed to the primacy of perception,

4.3

4.1

Ecophenomenology

Anticognitivist cognitive science

Merleau-Pontys critical position with respect to science

was stated in his Preface to the Phenomenology he described scientic points of view as always both naive

and at the same time dishonest. Despite, or perhaps

because of, this view, his work inuenced and anticipated the strands of modern psychology known as postcognitivism. Hubert Dreyfus has been instrumental in

emphasising the relevance of Maurice Merleau-Pontys

work to current post-cognitive research, and its criticism

of the traditional view of cognitive science.

5

dition, including Rosalyn Diprose and Sara Heinmaa

().

Rosalyn Diproses recent work takes advantage of

Merleau-Pontys conception of an intercorporeity, or

indistinction of perspectives, to critique individualistic

identity politics from a feminist perspective and to ground

the irreducibility of generosity as a virtue, where generosity has a dual sense of giving and being given.

Sara Heinmaa has argued for a rereading of MerleauPontys inuence on Simone de Beauvoir. (She has also

challenged Hubert Dreyfuss reading of Merleau-Ponty as

behaviorist, and as neglecting the importance of the pheDreyfuss seminal critique of cognitivism (or the compunomenological reduction to Merleau-Pontys thought.)

tational account of the mind), What Computers Can't Do,

consciously replays Merleau-Pontys critique of intellec- Merleau-Pontys phenomenology of the body has also

tualist psychology to argue for the irreducibility of corpo- been taken up by Iris Young in her renowned essay

real know-how to discrete, syntactic processes. Through Throwing Like a Girl, and its follow-up, "'Throwing

the inuence of Dreyfuss critique and neurophysiolog- Like a Girl': Twenty Years Later. Young analyzes the

ical alternative, Merleau-Ponty became associated with particular modalities of feminine bodily comportment as

neurophysiological, connectionist accounts of cognition. they dier from that of men. Young observes that while

a man who throws a ball puts his whole body into the

With the publication in 1991 of The Embodied Mind by

motion, a woman throwing a ball generally restricts her

Francisco Varela, Evan Thompson, and Eleanor Rosch,

own movements as she makes them, and that, generally,

this association was extended, if only partially, to another

in sports, women move in a more tentative, reactive way.

strand of anti-cognitivist or post-representationalist

Merleau-Ponty argues that we experience the world in

cognitive science: embodied or enactive cognitive sciterms of the I can that is, oriented towards certain

ence, and later in the decade, to neurophenomenology.

projects based on our capacity and habituality. Youngs

In addition, Merleau-Pontys work has also inuenced rethesis is that in women, this intentionality is inhibited and

searchers trying to integrate neuroscience with the prinambivalent, rather than condent, experienced as an I

ciples of chaos theory.[18]

cannot.

It was through this relationship with Merleau-Pontys

work that cognitive sciences aair with phenomenology

was born, which is represented by a growing number of 4.3 Ecophenomenology

works, including

Ecophenomenology can be described as the pursuit of the

Ron McClamrock's Existenial Cognition: Computa- relationalities of worldly engagement, both human and

tional Minds in the World (1995),

those of other creatures (Brown & Toadvine 2003).

Andy Clark's Being There (1997),

This engagement is situated in a kind of middle ground of

relationality, a space that is neither purely objective, be Naturalizing Phenomenology edited by Petitot et al. cause it is reciprocally constituted by a diversity of lived

(1999),

experiences motivating the movements of countless organisms, nor purely subjective, because it is nonetheless

Alva No's Action in Perception (2004),

a eld of material relationships between bodies. It is gov Shaun Gallagher's How the Body Shapes the Mind erned exclusively neither by causality, nor by intentionality. In this space of in-betweenness phenomenology can

(2005),

overcome its inaugural opposition to naturalism.[19]

Grammont, Franck Dorothe Legrand, and Pierre

David Abram explains Merleau-Pontys concept of

Livet (eds.) 2010, Naturalizing Intention in Action,

esh (chair) as the mysterious tissue or matrix that

MIT Press 2010 ISBN 978-0-262-01367-3.

underlies and gives rise to both the perceiver and the per The journal Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sci- ceived as interdependent aspects of its spontaneous activity, and he identies this elemental matrix with the inences.

terdependent web of earthly life.[20] This concept unites

subject and object dialectically as determinations within a

more primordial reality, which Merleau-Ponty calls the

4.2 Feminist philosophy

esh, and which Abram refers to variously as the anMerleau-Ponty has also been picked up by Australian and imate earth, the breathing biosphere, or the moreNordic philosophers inspired by the French feminist tra- than-human natural world. Yet this is not nature or the

6 NOTES

biosphere conceived as a complex set of objects and objective processes, but rather the biosphere as it is experienced and lived from within by the intelligent body

by the attentive human animal who is entirely a part of

the world that he, or she, experiences. Merleau-Pontys

ecophenemonology with its emphasis on holistic dialog

within the larger-than-human world also has implications

for the ontogenesis and phylogenesis of language, indeed

he states that language is the very voice of the trees, the

waves and the forest.[21] Merleau-Ponty himself refers to

that primordial being which is not yet the subject-being

nor the object-being and which in every respect baes

reection. From this primordial being to us, there is no

derivation, nor any break...[22] Among the many working notes found on his desk at the time of his death, and

published with the half-complete manuscript of The Visible and the Invisible, several make evident that MerleauPonty himself recognized a deep anity between his notion of a primordial esh and a radically transformed

understanding of nature. Hence in November 1960 he

writes: Do a psychoanalysis of Nature: it is the esh,

the mother.[23] And in the last published working note,

written in March 1961, he writes: Nature as the other

side of humanity (as esh, nowise as 'matter').[24]

Bibliography

[7] Lester Embree, Merleau-Pontys Examination of Gestalt

Psychology, Research in Phenomenology, Vol. 10

(1980): pp. 89121.

[8] Maurice Merleau-Ponty - Biography at egs.edu

[9] Lacan, Jacques. The Split between the Eye and the Gaze

(1964).

[10] Thomas Baldwin in Introduction to Merleau-Pontys The

World of Perception (New York: Routledge, 2008): 2.

[11] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Child Psychology and Pedagogy:

The Sorbonne Lectures 1949-1952. Translated by Talia

Welsh. Evanston: Northwestern University Press, 2010.

[12] Martin Jay, (1986), Marxism and Totality: The Adventures

of a Concept from Lukcs to Habermas, pages 36185.

[13] Martin Jay, (1986), Marxism and Totality: The Adventures

of a Concept from Lukcs to Habermas, page 361.

[14] For recent investigations of this question refer to the following: Nader El-Bizri, A Phenomenological Account of

the Ontological Problem of Space, Existentia MeletaiSophias, Vol. XII, Issue 34 (2002), pp. 345364; see

also the related analysis of space qua depth in: Nader ElBizri, La perception de la profondeur: Alhazen, Berkeley et Merleau-Ponty, Oriens-Occidens: sciences, mathmatiques et philosophie de lantiquit lge classique

(Cahiers du Centre dHistoire des Sciences et des Philosophies Arabes et Mdivales, CNRS), Vol. 5 (2004), pp.

171-184. Check also the connections of this question with

Heideggers accounts of the phenomenon of dwelling in:

Nader El-Bizri, 'Being at Home Among Things: Heideggers Reections on Dwelling', Environment, Space, Place

3 (2011), pp. 4771

The following table gives a selection of Merleau-Pontys

works in French and English translation. A much more

comprehensive bibliography can be found through the

Merleau-Ponty Circle website: Bibliography of Primary

Sources at Merleau-Ponty Circle. URI Department of [15] See: Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure, Andr

Malrauxs Theory of Art, Rodopi, 2009.

Philosophy. Retrieved June 11, 2011.

Notes

[1] Lawrence Hass & Dorothea Olkoskwi.

Rereading

Merleau-Ponty: Essays Beyond the Continental-Analytic

Divide. Humanity Books. 2000.

[16] Derek Allan, Art and the Human Adventure: Andr Malrauxs Theory of Art, Rodopi, 2009.

[17] Emmanuel Alloa, Merleau-Ponty, tout un roman,

Le Monde | 23.10.2014 https://www.academia.edu/

9041201/Un_roman_de_jeunesse_de_Merleau-Ponty_

Nord_r%C3%A9cit_de_lArctique_1928_

[2] Martin C. Dillon, Merleau-Ponty Vivant, SUNY Press,

1991, p. 63.

[18] Skada, Christine; Walter Freedman (March 1990).

Chaos and the New Science of the Brain. Concepts in

Neuroscience 1: 275285.

[3] Evan Thompson, Mind in Life: Biology, Phenomenology,

and the Sciences of Mind, Harvard University Press, 2007,

p. 313.

[19] Charles Brown and Ted Toadvine, (Eds) (2003). EcoPhenomenology: Back to the Earth Itself. Albany: SUNY

Press.

[4] Mark A. Wrathall, Je E. Malpas (eds), Heidegger, Coping, and Cognitive Science - Volume 2, MIT Press, 2000 ,

p. 167.

[20] Abram, D. (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception

and Language in a More-than Human World. Pantheon

Books, New York. p. 66.

[5] Maurice Merleau-Ponty, The Primacy of Perception,

Northwestern University Press, 1964, p. 3.

[21] Abram, D. (1996). The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception

and Language in a More-than Human World. Pantheon

Books, New York. p. 65.

[6] Richard L. Lanigan, Speaking and Semiology: Maurice

Merleau-Pontys Phenomenological Theory of Existential

Communication, Walter de Gruyter, 1991, p. 49.

[22] The Concept of Nature, I, Themes from the Lectures at the

Collge de France 1952-1960. Northwestern University

Press. 1970. pp. 6566.

[23] The Visible and the Invisible. Northwestern University

Press. 1968. p. 267.

Popen, Shari, 1995, "Merleau-Ponty Confronts

Postmodernism: A Reply to OLoughlin."

[24] The Visible and the Invisible. Northwestern University

Press. 1968. p. 274.

Merleau-Ponty: Reckoning with the Possibility of

an 'Other.'

The Journal of French Philosophy the online

home of the Bulletin de la Socit Amricaine de

Philosophie de Langue Franaise

References

Abram, D. (1988) Merleau-Ponty and the Voice of

the Earth. Environmental Ethics 10, no. 2 (Summer

1988): 101-20.

Clark, A. 1997. Being There: Putting Brain, Body,

and World Together Again. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Gallagher, Shaun 2003. How the Body Shapes the

Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

No, A. Action in Perception. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Petitot, J., Varela, F., Pachoud, B. and Roy, J-M.

(eds.). 1999. Naturalizing Phenomenology: Issues

in Contemporary Phenomenology and Cognitive Science. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Xavier Tilliette, Maurice Merleau-Ponty ou la

mesure de l'homme, Seghers, 1970.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E. and Rosch, E. 1991.

The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human

Experience. Cambridge: MIT Press.

External links

Quotations related to Maurice Merleau-Ponty at

Wikiquote

Maurice Merleau-Ponty at 18 from the French Government website

English Translations of Merleau-Pontys Work

Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Merleau-Ponty by Jack Reynolds

Maurice

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

Merleau-Ponty by Bernard Flynn

Maurice

The Merleau-Ponty Circle Association of scholars interested in the works of Merleau-Ponty

Maurice Merleau-Ponty page at Mythos & Logos

Chiasmi International Studies Concerning the

Thought of Maurice Merleau-Ponty in English,

French and Italian

OLoughlin, Marjorie, 1995, "Intelligent Bodies and

Ecological Subjectivities: Merleau-Pontys Corrective to Postmodernisms Subjects of Education."

Online Merleau-Ponty Bibliography at PhilPapers.org

9 TEXT AND IMAGE SOURCES, CONTRIBUTORS, AND LICENSES

Text and image sources, contributors, and licenses

9.1

Text

Maurice Merleau-Ponty Source: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maurice%20Merleau-Ponty?oldid=643724172 Contributors: Brion VIBBER, TUF-KAT, TUF-KAT, Poor Yorick, Andres, TonyClarke, Giddytrace, Rbellin, Robbot, Fredrik, Diderot, Everyking, DO'Neil,

JillandJack, Andycjp, Phil Sandifer, Esperant, D6, NightMonkey, Simonides, Rich Farmbrough, Martpol, Bender235, Kwamikagami,

Bookofjude, Whosyourjudas, Cmdrjameson, Pearle, Mark Dingemanse, Gary123, Bbsrock, Omphaloscope, Dirac1933, Tedpennings,

Patrice Ltourneau, Jtauber, Velho, Woohookitty, Kzollman, Scjessey, Kam Solusar, Tevatron, David Levy, Koavf, Ligulem, The wub,

FlaBot, Pruneau, Moskvax, Happeningsh, Lilypepper, JYOuyang, Stevenfruitsmaak, Aethralis, YurikBot, RobotE, NTBot, RussBot, Pigman, Krits, Bota47, Cesarsorm, Marquez, Harthacnut, SmackBot, Ldh214, MattieTK, Lestrade, Monty Cantsin, LonesomeDrifter, David

Ludwig, Chris the speller, TimBentley, Josteinn, Bsilverthorn, WikiPedant, Laputan, Byelf2007, Lapaz, Tazmaniacs, Kafkan, MTSbot,

Christian Roess, Peter1c, Lazulilasher, To hell with poverty!, Gregbard, Cydebot, Peterdjones, ST47, Bomzhik, Brobbins, Alharris, Heraldman, Agnaramasi, Escarbot, M cua, D. Webb, Matthew Fennell, Vandymorgan, C. C. Perez, .anacondabot, Magioladitis, Appraiser,

Ling.Nut, Justice for All, Lucaas, Max18well, EagleFan, Businessman332211, JaGa, Shimwell, Mtevfrog, Johnpacklambert, Sophomaniac,

Tikiwont, Johnbod, Binris, Milynchke, Inwind, S, DASonnenfeld, Jvpwiki, Rmih, Jonas Mur, Martinevans123, TXiKiBoT, Tomsega,

Cameralumina, Tedcooke, Profronrowe, Tomasboij, BotMultichill, Platinumbuddha, Arpose, Stephendcole, Corrado7mari, Firstwingman,

Monegasque, Vojvodaen, Calen11, Tradereddy, ClueBot, EoGuy, Nick.s.barnett, Addacat, Alexbot, Herondance, Aleksd, If I was Half Pint,

XLinkBot, Hjsilverman, RogDel, Dubmill, Fyrael, Phcople, Phenomenologique, AnnaFrance, Luckas-bot, Yobot, Pink!Teen, Andreasmperu, Denispir, Citation bot, Augarten10, Xqbot, Ninjaphilosopher, Glenmazis, J04n, Omnipaedista, D'ohBot, CircleAdrian, Chris09j,

Esprit Gamin, Jujutacular, Wilk2695, RjwilmsiBot, WikitanvirBot, Davidjonathanmorris, ZroBot, SporkBot, Albinoni67, Polisher of

Cobwebs, Davemnt, Mjbmrbot, ClueBot NG, PT14danang, Helpful Pixie Bot, Titodutta, AlterBerg, PhnomPencil, Theol11111, Wallpaperit, Factndersonline, ChristianShabo, Bodyphilosopher, Eb7473, Dlandes, Rcalore, Tipasaweb, Kernsters, Tekvern, Depthdiver, NSFralin, Monkbot and Anonymous: 132

9.2

Images

File:CHINTREUIL_-_Le_Boulot_blanc.JPG Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/45/CHINTREUIL_-_Le_

Boulot_blanc.JPG License: Public domain Contributors: Own work Original artist: PHILDIC

File:Commons-logo.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/4a/Commons-logo.svg License: ? Contributors: ? Original

artist: ?

File:Ferdinand_de_Saussure.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8f/Ferdinand_de_Saussure.jpg License:

Public domain Contributors: ? Original artist: ?

File:Folder_Hexagonal_Icon.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/4/48/Folder_Hexagonal_Icon.svg License: Cc-bysa-3.0 Contributors: ? Original artist: ?

File:Frans_Hals_-_Portret_van_Ren_Descartes.jpg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/73/Frans_Hals_-_

Portret_van_Ren%C3%A9_Descartes.jpg License: Public domain Contributors: Andr Hatala [e.a.] (1997) De eeuw van Rembrandt,

Bruxelles: Crdit communal de Belgique, ISBN 2-908388-32-4. Original artist: After Frans Hals (1582/15831666)

File:Merleau-Ponty{}s_grave.jpeg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/af/Merleau-Ponty%27s_grave.jpeg License: CC BY-SA 3.0 Contributors: Own work Original artist: User:CircleAdrian

File:Portal-puzzle.svg Source: http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/en/f/fd/Portal-puzzle.svg License: Public domain Contributors: ?

Original artist: ?

9.3

Content license

Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0

You might also like

- Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenological Philosophy of Mind and BodyDocument34 pagesMerleau-Ponty's Phenomenological Philosophy of Mind and BodyThangneihsialNo ratings yet

- Earth Day: Vision for Peace, Justice, and Earth Care: My Life and Thought at Age 96From EverandEarth Day: Vision for Peace, Justice, and Earth Care: My Life and Thought at Age 96No ratings yet

- Playing With PoverDocument13 pagesPlaying With PoveremiliosasofNo ratings yet

- M1-Lesson 2 (Art Appreciation)Document21 pagesM1-Lesson 2 (Art Appreciation)Joecel PeligonesNo ratings yet

- Category of BeingDocument10 pagesCategory of BeingAdHominem1997No ratings yet

- Archaeologies of The SensesDocument18 pagesArchaeologies of The SensesManos LambrakisNo ratings yet

- Shaun GallagherDocument2 pagesShaun GallagherZeus Herakles100% (1)

- De Thi Cao Hoc 2Document49 pagesDe Thi Cao Hoc 2Nguyen Ngoc KhuongNo ratings yet

- Deep Ecology Debate on Humans' Environmental RoleDocument8 pagesDeep Ecology Debate on Humans' Environmental RoleVidushi ThapliyalNo ratings yet

- Claude Lévi - Strauss-The Savage Mind - Weidenfeld and Nicolson (1966)Document152 pagesClaude Lévi - Strauss-The Savage Mind - Weidenfeld and Nicolson (1966)Alexandra-Florentina Peca0% (1)

- Merleau-Ponty On The BodyDocument16 pagesMerleau-Ponty On The BodyIsabel ChiuNo ratings yet

- Flesh. Toward A History of The MisunderstandingDocument14 pagesFlesh. Toward A History of The MisunderstandingRob ThuhuNo ratings yet

- Ecocriticism: An Essay: The Ecocriticism Reader Harold Fromm Lawrence BuellDocument10 pagesEcocriticism: An Essay: The Ecocriticism Reader Harold Fromm Lawrence BuellMuHammAD ShArjeeLNo ratings yet

- NAESS, Arne and SESSIONS, George - Basic Principles of Deep EcologyDocument7 pagesNAESS, Arne and SESSIONS, George - Basic Principles of Deep EcologyClayton RodriguesNo ratings yet

- The Japanese AvantGarde - Toshiko EllisDocument20 pagesThe Japanese AvantGarde - Toshiko EllisJuan Manuel Gomez GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Translation As Means of Communication in Multicultural WorldDocument4 pagesTranslation As Means of Communication in Multicultural WorldLana CarterNo ratings yet

- About Installation Art PDFDocument3 pagesAbout Installation Art PDFJohn SenpieNo ratings yet

- Art As Technique ShklovskyDocument2 pagesArt As Technique Shklovskybharan16No ratings yet

- Deep Ecology: L.Sri Lasya CB - EN.U4EEE15030Document19 pagesDeep Ecology: L.Sri Lasya CB - EN.U4EEE15030Meenakshi Saji100% (1)

- 4 Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) Correspondences: CorrespondancesDocument3 pages4 Charles Baudelaire (1821-1867) Correspondences: CorrespondancesJeremy DavisNo ratings yet

- Karl Popper's Falsification PhilosophyDocument19 pagesKarl Popper's Falsification PhilosophyAlvin Francis F. LozanoNo ratings yet

- Phenomenology and Danc. Husserlian MeditationsDocument17 pagesPhenomenology and Danc. Husserlian MeditationsRosa CastilloNo ratings yet

- The Wilderness Idea ReaffirmedDocument8 pagesThe Wilderness Idea ReaffirmedCenter for Respect of Life and EnvironmentNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 4 PDFDocument70 pages09 - Chapter 4 PDFujjwal kumarNo ratings yet

- Environmental Humanities 8 1 Multispecies Studies 2016Document151 pagesEnvironmental Humanities 8 1 Multispecies Studies 2016Emmanuel AlmadaNo ratings yet

- Touching, FlirtingDocument13 pagesTouching, FlirtinganatecarNo ratings yet

- Isaac Newton's Views on the TrinityDocument13 pagesIsaac Newton's Views on the TrinityФратер ФениксNo ratings yet

- Nature - Course Notes From The College de FranceDocument334 pagesNature - Course Notes From The College de FranceMauricio Gomes100% (6)

- Integrating Dance and Reading ComprehensionDocument39 pagesIntegrating Dance and Reading Comprehensionapi-284991195100% (1)

- Modern-Art SkjdkaljDocument33 pagesModern-Art SkjdkaljVince Bryan San PabloNo ratings yet

- The Literary Phenomenon of Free Indirect Speech: Alina LESKIVDocument8 pagesThe Literary Phenomenon of Free Indirect Speech: Alina LESKIVcatcthetime26No ratings yet

- Borges On Life and DeathDocument6 pagesBorges On Life and DeathLado Beridze100% (1)

- P. Adams Sitney On The Films of Nathaniel DorskyDocument9 pagesP. Adams Sitney On The Films of Nathaniel DorskystriduraNo ratings yet

- I. What Is Literature Criticism?Document6 pagesI. What Is Literature Criticism?Ga MusaNo ratings yet

- Raymond WilliamsDocument1 pageRaymond WilliamszouadraNo ratings yet

- Arnheim - Art Among Objects.1987Document10 pagesArnheim - Art Among Objects.1987Martha SchwendenerNo ratings yet

- Williams - Ideas of NatureDocument10 pagesWilliams - Ideas of NatureJerry ZeeNo ratings yet

- Reading The Visual by Mark ThorsbyDocument10 pagesReading The Visual by Mark Thorsbythorm197No ratings yet

- Study Guide For Kawabata's "Of Birds and Beasts"Document3 pagesStudy Guide For Kawabata's "Of Birds and Beasts"BeholdmyswarthyfaceNo ratings yet

- Gayatri Chakravorty SpivakDocument9 pagesGayatri Chakravorty SpivakDjordjeNo ratings yet

- Act.2 - Art of Emerging EuropeDocument10 pagesAct.2 - Art of Emerging EuropeRafael Lopez CargoNo ratings yet

- Aesthetic DisobedienceDocument12 pagesAesthetic DisobedienceAna Lucero TroncosoNo ratings yet

- Empathy and Wolfflin - Bridge2011Document20 pagesEmpathy and Wolfflin - Bridge2011Miguel Córdova RamirezNo ratings yet

- A Pattern LanguageDocument1 pageA Pattern LanguageMaria KhanNo ratings yet

- Social AnthropologyDocument2 pagesSocial AnthropologyNicole Williams0% (1)

- Moved To Dance Remix Rasa and A New Indi PDFDocument19 pagesMoved To Dance Remix Rasa and A New Indi PDFdrystate1010No ratings yet

- Tim IngoldDocument6 pagesTim IngoldYasmin MonteiroNo ratings yet

- Nancy Jean Luc L Intrus EnglishDocument14 pagesNancy Jean Luc L Intrus EnglishJosé Sarmiento HinojosaNo ratings yet

- John MiltonDocument17 pagesJohn MiltonCristina HistoryTeacherNo ratings yet

- Aristophanes and Euripides. A Palimpsestuous RelationshipDocument260 pagesAristophanes and Euripides. A Palimpsestuous RelationshipAlmasyNo ratings yet

- Latour, Bruno. (2013) Biography of An Inquiry On A Book About Modes of ExistenceDocument16 pagesLatour, Bruno. (2013) Biography of An Inquiry On A Book About Modes of ExistencerafaelfdhNo ratings yet

- Ge1 - Topic OutlineDocument3 pagesGe1 - Topic Outlinegeyb awayNo ratings yet

- Maurice Jean Jacques Merleau-PontyDocument2 pagesMaurice Jean Jacques Merleau-PontyHoney jane RoqueNo ratings yet

- MerleauDocument17 pagesMerleauadfsNo ratings yet

- The Logos of the Sensible World: Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenological PhilosophyFrom EverandThe Logos of the Sensible World: Merleau-Ponty's Phenomenological PhilosophyNo ratings yet

- Report MAN AS EMBODIED SUBJECTIVITYDocument7 pagesReport MAN AS EMBODIED SUBJECTIVITYCute TzyNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument53 pagesPDFkenadia11No ratings yet

- 14iros ColtinVeloso PDFDocument6 pages14iros ColtinVeloso PDFkenadia11No ratings yet

- Conda CheatsheetDocument2 pagesConda CheatsheetJohnNo ratings yet

- 14iros ColtinVeloso PDFDocument6 pages14iros ColtinVeloso PDFkenadia11No ratings yet

- Conda CheatsheetDocument2 pagesConda CheatsheetJohnNo ratings yet

- Ken Schiller ResumeDocument1 pageKen Schiller Resumekenadia11No ratings yet

- Mammals and Cryptozoology: Objective Evidence vs. Circumstantial ClaimsDocument20 pagesMammals and Cryptozoology: Objective Evidence vs. Circumstantial Claimskenadia11No ratings yet

- Fanon and The Land Question in (Post) Apartheid South AfricaDocument12 pagesFanon and The Land Question in (Post) Apartheid South AfricaTigersEye99No ratings yet

- ANALYSIS OF ARMS AND THE MAN: EXPLORING CLASS, WAR, AND IDEALISMDocument3 pagesANALYSIS OF ARMS AND THE MAN: EXPLORING CLASS, WAR, AND IDEALISMSayantan Chatterjee100% (1)

- Upper Int U9 APerformanceAppraisalForm PDFDocument2 pagesUpper Int U9 APerformanceAppraisalForm PDFZsuzsa StefánNo ratings yet

- BVDoshi's Works and IdeasDocument11 pagesBVDoshi's Works and IdeasPraveen KuralNo ratings yet

- Spatial Locations: Carol DelaneyDocument17 pagesSpatial Locations: Carol DelaneySNo ratings yet

- Be Yourself, But CarefullDocument14 pagesBe Yourself, But Carefullmegha maheshwari50% (4)

- ARTH212 SyllabusDocument4 pagesARTH212 Syllabusst_jovNo ratings yet

- Communication Technology and Society Lelia Green PDFDocument2 pagesCommunication Technology and Society Lelia Green PDFJillNo ratings yet

- Fine Ten Lies of EthnographyDocument28 pagesFine Ten Lies of EthnographyGloria IríasNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Learning Management System (LMS) Case Study at Open University Malaysia (OUM), Kota Bharu CampusDocument7 pagesThe Effectiveness of Learning Management System (LMS) Case Study at Open University Malaysia (OUM), Kota Bharu Campussaeedullah81No ratings yet

- Outrageous Conduct Art Ego and The Twilight Zone CaseDocument34 pagesOutrageous Conduct Art Ego and The Twilight Zone CaseMayuk K0% (9)

- Ergonomic Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesErgonomic Lesson Planapi-242059317100% (3)

- Decoding China Cross-Cultural Strategies For Successful Business With The ChineseDocument116 pagesDecoding China Cross-Cultural Strategies For Successful Business With The Chinese卡卡No ratings yet

- El Narrador en La Ciudad Dentro de La Temática de Los Cuentos deDocument163 pagesEl Narrador en La Ciudad Dentro de La Temática de Los Cuentos deSimone Schiavinato100% (1)

- Combine Group WorkDocument32 pagesCombine Group WorkTAFADZWA K CHIDUMANo ratings yet

- reviewer ノಠ益ಠノ彡Document25 pagesreviewer ノಠ益ಠノ彡t4 we5 werg 5No ratings yet

- Compound Interest CalculatorDocument4 pagesCompound Interest CalculatorYvonne Alonzo De BelenNo ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument15 pagesResearch ProposalZainab AhmedNo ratings yet

- Alexander vs. Eisenman 1983Document18 pagesAlexander vs. Eisenman 1983ptr-pnNo ratings yet

- BMU Diamante Poem RubricDocument2 pagesBMU Diamante Poem RubricLina Cabigas Hidalgo100% (1)

- 12 Angry MenDocument20 pages12 Angry MenKetoki MazumdarNo ratings yet

- JobStart Philippines Life Skills Trainer's ManualDocument279 pagesJobStart Philippines Life Skills Trainer's ManualPaul Omar Pastrano100% (1)

- EQUADORDocument8 pagesEQUADORAakriti PatwaryNo ratings yet

- Theoretical foundations community health nursingDocument26 pagesTheoretical foundations community health nursingMohamed MansourNo ratings yet

- Grammar Within and Beyond The SentenceDocument3 pagesGrammar Within and Beyond The SentenceAmna iqbal75% (4)

- Heidegger's LichtungDocument2 pagesHeidegger's LichtungRudy BauerNo ratings yet

- 6.1, The Rise of Greek CivilizationDocument18 pages6.1, The Rise of Greek CivilizationLeon GuintoNo ratings yet

- Toefl 101 PDFDocument2 pagesToefl 101 PDFmihai_bors_010% (1)

- NECO 2020 BECE EXAM TIMETABLEDocument1 pageNECO 2020 BECE EXAM TIMETABLEpaulina ineduNo ratings yet