Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Envisioning Sustainability Three-Dimensionally

Uploaded by

Paco SalazarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Envisioning Sustainability Three-Dimensionally

Uploaded by

Paco SalazarCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Cleaner Production

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jclepro

Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally

Rodrigo Lozano*

B.R.A.S.S. Research Centre, Cardiff University, 55 Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3AT, United Kingdom

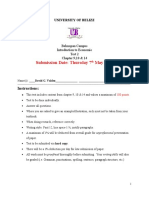

a r t i c l e i n f o

a b s t r a c t

Article history:

Received 12 July 2007

Received in revised form 25 February 2008

Accepted 26 February 2008

Available online 18 April 2008

Sustainability has arisen as an alternative to the dominant socio-economic paradigm (DSP). However, it is

still a difcult concept for many to fully understand. To help to communicate it and make it more tangible

visual representations have been used. Three of the most used, and critiqued, sustainability representations are: (1) a Venn diagram, i.e. three circles that inter-connect, where the resulting overlap that

represents sustainability can be misleading; (2) three concentric circles, the inner circle representing

economic aspects, the middle social aspects, and the outer environmental aspects; and (3) the Planning

Hexagon, showing the relationships among economy, environment, the individual, group norms, technical skills, and legal and planning systems. Each has been useful in helping to engage the general public

and raising sustainability awareness. However, they all suffer from being highly anthropocentric, compartmentalised, and lacking completeness and continuity. These drawbacks have reduced their acceptance and use by more advanced sustainability scholars, researchers and practitioners. This paper

presents an innovative attempt to represent sustainability in three dimensions which show the complex

and dynamic equilibria among economic, environmental and social aspects, and the short-, long- and

longer-term perspectives.

2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords:

Sustainable development

Sustainability

Graphical representations

Venn diagram

Concentric circles

1. Introduction

During the last 30 years, there have been unprecedented advances in development and industrialisation, with results such as

increase of up to 20 years in life expectancy in developing countries,

infant mortality rates have halved, literacy rates have risen, food

production and consumption have increased faster than population

rates, incomes have improved, and there has been a spread in

democratically elected governments [14]. However, it is increasingly recognised that such activities have been detrimental to

economic, environmental, and social aspects. This has raised concerns that the resulting damage to the earths environment and

quality of life for future generations will be irreparable [13,5,6]. In

addition, conventional scientic traditions based on reductionistic

causeeffect relationships are failing to explain and address the

complex dynamic inter-relations among economic, environmental,

and social aspects, and the time perspective [79]. The concept of

Sustainable Development (SD) has appeared as an alternative to

help understand and restore the equilibria among these.

Although the roots SD concept can be traced back to the concept

of Sustainable Societies which appeared in 1974 [10], it was the

Brundtland Report [3] which brought it to the mainstream

* Tel.: 44 (0) 29 20 876562, 7981900984 (mobile); fax: 44 (0) 29 20 876061.

E-mail address: lozanorosr@cardiff.ac.uk.

URL: http://www.brass.cardiff.ac.uk

0959-6526/$ see front matter 2008 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2008.02.008

international political agenda by creating a simple denition that

became widely quoted worldwide [6]. The WCEDs [3] denes SD

as: .development that meets the needs of the present without

compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own

needs [3].

Many other authors have sought to dene SD, with at least 70

different denitions that were compiled by 1992 [11]. Some denitions have focused only on environmental sustainability, e.g. see

Refs. [1221], principally through the use of natural resources

without going beyond their carrying capacities and the production

of pollutants without passing the biodegradation limits of receiving

system. These denitions have been usually developed by scientists

from countries and seldom consider the importance of social aspects (e.g. human rights, corruption, poverty, illiteracy, and child

mortality) and their inter-relations with economic and environmental aspects. In societies and countries where the basic human

needs, such as food, shelter and security, have not been fullled the

environmental sustainability is often neglected.

It is possible to separate the different SD denitions into the

following categories: (1) conventional economists perspective; (2)

non-environmental degradation perspective; (3) integrational

perspective, i.e. encompassing the economic, environmental, and

social aspects; (4) inter-generational perspective; and (5) holistic

perspective. In some cases the boundaries between perspectives

may be blurred.

In the conventional economists perspective, sustainability

suggests a steady state [22], with normative characteristics,

R. Lozano / Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

1839

Fig. 3. Sustainability representation using non-concentric adjacent circles. Source:

adapted from Refs. [18,49,50].

Fig. 1. Graphical representation of sustainability using a Venn diagram. Source:

adapted from Refs. [2,40,4850].

and implying efciency, i.e. the choice of a feasible level of consumption [23]. According to Goldin and Winters [22] economists

have neither the theoretical nor the empirical tools to predict the

impact of economic activities on the environment. This perspective

sees SD as no more than an element of a desirable development

path [23]. It also confuses sustainability with economic viability, i.e.

sustained growth and self-sufciency [24]. Such perspective has

very limited scope, neglecting the impacts of economic activities

upon the environment and societies of today, and certainly in the

future. It attempts to simplify into economic terms natural and

social phenomena. Bartelmus [25] stated that the value of the environment cannot be expressed in monetary terms. Equally, the

value of societies and their individuals cannot be put in monetary

terms. It is not possible to price the life of a human being, even if

corporations and governments try to through compensation systems, e.g. the use of Pareto principle to changes in accidents and

fatalities [26].

The non-environmental degradation perspective, with environmental economics as its main discipline, came as an alternative

way to consider industrialisations negative effects on the environment. Two of the key authors of this group include Daly [27] and

Costanza [13]. The denitions in this group converge in remarking

that resources are scarce, consumption cannot be continued indenitely, natural resources should be used without surpassing

their carrying capacities, and environmental capital should not be

depleted [10,1317,1921,2732]. In the majority of the cases, SD

has primarily environmental connotations, e.g. see Refs. [1217,19

22,29,32,33]. Such connotations, in many cases come from individuals or groups from developed countries and do not consider

the importance of social aspects, such as the interrelation between

the environment and human rights, corruption, poverty, illiteracy,

child mortality, and epidemics, amongst many others. A valid

argument to consider in relation to this is that when any individuals

and societies have not fullled their basic needs the long-term

safeguarding of the environment becomes relatively unimportant,

at least in the short-term. This perspective also fails to address the

inter-relations among the aspects. This is in part explained by difculties in analysing social systems [34].

Within the integrational perspective the key characteristic is the

integration of economic, environmental, and social aspects, and the

relations among them [2,5,30,33,35]. The following quote is a key

example of this perspective: Sustainable Development involves the

simultaneous pursuit of economic prosperity, environmental quality,

and social equity [35]. There are many overlaps among the aspects

[33], but they are not necessarily balanced [30]. This perspective is,

comparatively, more complete than the previous two. Nevertheless,

it lacks continuity, the interactions among the short-, long-, and

longer-term, focusing mainly on current activities.

The inter-generational perspective main focus is on the time

perspective, by taking into consideration the long-term effects of

todays decisions, as the Brundtland Report [3] indicates of

Fig. 2. Graphical representation of sustainability using concentric circles. Source:

adapted from Ref. [48].

Fig. 4. The systems of SD underscoring the relationships among the local, national and

global levels and underscoring the need to integrate the social, economic and the

environmental in a more holistic manner. Source: adapted from Refs. [2,40].

1840

R. Lozano / Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

Fig. 5. The Planning Hexagon: relations among economic/money trade, individual/personal beliefs, group norms/culture society, technical/administrative skills, legal/political

systems, and physical/biological sources. Source: adapted from Refs. [51,52].

Fig. 6. Equalizing and merging economic, environmental, and social aspects (1Vd ).

satisfying the needs of todays societies without compromising the

needs of tomorrows societies. Some of the authors taking this

perspective include Goldin and Winters [22], the WCED [3], Hodge

et al. [36], Langer and Schon [30], Stavins et al. [23], Hussey et al.[37],

Reinhardt [32], Bhaskar and Glyn [38], Atkinson [12], Diesendorf

[33], and Stavins et al. [23]. Although this perspectives forte is its

focus on continuity, in some cases it does not explicitly integrate the

other aspects. Sometimes this perspective is critiqued as being too

broad and vague, and difcult to ground in practical activities [11].

The holistic perspective explicitly combines the integrational

and inter-generational perspectives. Some of the authors taking

this perspective include Elsen [39], Lozano-Ros [40], and Lozano

[24,41]. This perspective proposes two dynamic and simultaneous

equilibria: the rst one amongst economic, environmental and

social aspects,1 and the second amongst the temporal aspects, i.e.

short-, long- and longer-term perspectives.

Although it is common to nd the terms Sustainable Development and Sustainability used interchangeably, they are inherently different. Reid [6], Lozano-Ros [40], and Martin [42] state

that the difference lies in SD being the journey, path or process to

Stakeholder participation is part of the social aspects.

achieve sustainability, i.e. the .capacity for continuance into the

long-term future [42] or the ideal dynamic state.

2. Envisioning sustainability

Different authors have appealed to the use of images, graphical

representations, and models to help explain, raise awareness, and

increase understanding and diffusion rates of complex concepts, as

in the case of sustainability [12]. The use of images can improve

learning and understanding of new or complex concepts, such as

sustainability, especially when images are carefully selected and

constructed to complement written text and not substitute it [43

47]. In many cases, images are easier to remember than non-image

data. They can also help to make the text more compact or concise,

concrete, coherent, comprehensible, correspondent and codeable

[sic] [43,44]. Visual representations can help to communicate,

generalise and make more tangible concepts that are difcult to

express clearly and succinctly with words, such as sustainability.

However, even those professionally designed may not be perfect,

instead of helping in the learning and understanding processes,

they may have the opposite impact [44].

Among the different sustainability graphical representations

used two stand out: (1) the Venn diagram (see Fig. 1) [2,40,4850],

R. Lozano / Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

1841

Fig. 7. Integrating the economic, environmental, and social aspects to achieve full interrelatedness (2Vd ).

Fig. 8. Transformation towards the First Tier Sustainability Equilibrium. Interactions among economic, environmental, and social aspects from the Venn diagram (FTSE).

Fig. 9. Continuous interrelatedness among economic, environmental, and social aspects through concentric circles (1CC ).

where the union created by the overlap among the three components of economy, environment and society are designed to represent sustainability; and (2) concentric circles, where the outer

circle represents the natural environment, the middle one represents society, and the inner one represents economic aspects (see

Fig. 2) [48]. Some authors propose a model with embedded circles

but no concentricity or common middle point, e.g. Refs. [18,49,50]

(see Fig. 3). These representations are mainly based on the integrational perspective.

Dalal-Clayton and Bass [2] complement the Venn diagram representation by adding local, national, and global perspectives,

which encompass four societal inuences: politics, peace and

1842

R. Lozano / Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

Fig. 10. Transformation towards the First Tier Sustainability Equilibrium. Interactions among economic, environmental, and social aspects from concentric circles (FTSE).

Fig. 11. Intergenerational sustainability, designed to safeguard the rights and abilities of future generations to also meet their needs. Source: adapted from Ref. [40].

security, cultural values, and institutional and administrative

arrangements. Lozano-Ros [40] incorporates technology as an

additional societal factor (see Fig. 4).

Another lesser known graphical model is the Planning Hexagon

[51,52] (see Fig. 5), which is designed to model the relationships

among economy, environment, the individual, group norms, technical skills, as well as legal and planning systems.

These representations provide basic sustainability understanding, especially of the interaction of the three aspects. They

are helpful in raising awareness for the general public. However,

they suffer from different drawbacks.

In the Venn diagram sustainability is represented by the overlapping area of the three circles, shown as full (F) in Fig. 1. The

areas lying outside of this are considered either as partial sustainability (P), the union of two circles, or not at all related to

sustainability. This implies that sustainability is only those aspects

where the three aspects are united. This is awed since it considers

sustainability to be compartmentalised and disregards the interconnectedness within and among the three aspects. Another aw

of this representation is being a mere snapshot of a moment in

time, which lacks the ability to represent the dynamic processes of

change over time.

The concentric circles model, Fig. 2, depicts a large circle or

system, the natural environment, with a subsystem society,

which has a further subsystem, the economy. Here, society is

a part of nature, and the economy is a part of society. Nonetheless,

the delimiting of the three aspects by the use of circles does not

really reect the complex inter-connectedness that actually exists

among them. An example of such interrelatedness is presented by

Hart [53] who argues that a conict appears when a population

starts invading natural reserves to obtain food and other short-term

subsistence resources, such as re-wood. In this case, humans take

Fig. 12. The Natural Step framework funnel. Adapted from Ref. [62].

Fig. 13. Integrating the time dimension into the rst tier equilibrium (3D-Sust).

R. Lozano / Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

Fig. 14. Disequilibrium in the time dimension. Lack of long-term perspective.

resources from the environment, breaking out of the social circle.

It might be argued that in a sustainable society there would be no

need to take resources outside of natural resources that are

assigned for the use of the social system, but this implies that

there are sufcient resources with no external factors (e.g. climate

disasters, or political and military conicts) leading to reductions in

supply for the subsistence of a society. This has proven to be ever

more difcult, especially in recent decades when economic and

social activities are increasingly expanding and destroying the

natural environment throughout the entire Earth; in the process

humans, with a population of over 6.3 billion, are rapidly overwhelming the natural environments carrying capacities [5456].

This helps to show that the concentric circles model is highly anthropocentric, implying that economy is at the centre of sustainability; typical in Western countries. This conicts with the idea of

balance among the three components. As with the Venn diagram it

compartmentalises each of the aspects and lacks the dynamics of

process change over time.

The Planning Hexagon provides explicit relationships among

economy, environment, the individual, group norms, technical

skills, and legal and planning systems; opposite to the previous

where the last four elements are included in the social aspects. As

with the other representations it compartmentalises the relationships, and does not address the dynamic time dimensions. As with

the Venn diagram and concentric circles, the Planning Hexagon can

also be considered to belong to the integrational perspective.

It is evident that these approaches seek to illustrate the complex

concept of sustainability in a simple manner through graphical

representations. Each representation has its strengths, such as ease

of understanding and power of depiction to reach the general

public. However, they all suffer from issues of scale; being centred

on one point in time, being highly anthropocentric and compartmentalised;

and

lacking

conceptual

coherence,

interconnectedness among the aspects, completeness, trans-disciplinarity, and dynamic time dimensions. These drawbacks have

reduced their acceptance and use by more advanced sustainability

scholars, researchers and practitioners.

Representing the sustainability concept fully and accurately

through graphical means is more difcult than it appears, but it is

also clearly an important task to achieve. The following section

focuses on an innovative attempt to represent sustainability in

three dimensions, which is aimed to show the complex and

dynamic equilibria among economic, environmental and social

aspects, and the short-, long- and longer-term.

3. Envisioning sustainability three-dimensionally

Useful tools for envisaging concepts rarely arrive fully formed;

usually they are developed though an evolutionary process. The

1843

following paragraphs explain the mental process that the author

went through to develop a new way of envisioning the vastness and

complexity of sustainability.

Modern societies that follow the dominant socio-economic

paradigm (DSP), neo-liberal capitalism, are based on the importance and centrality of economic aspects, and a tergiversated Free

Trade, which are raping the Earth for natural resources and societies [2,54,57]. History has shown that capitalism has not been

alone in these processes. Socialism and communism also disregarded the impacts of industrialisation on the environment, as

the Aral Seas shrinking dimensions and increasing salinity bear

witness [58,59]. In all cases, the central importance has been given

to economic aspects, under the names of development2 and

industrialisation, while impacting or disregarding the environment

and societies. This is shown in the left side of Fig. 6, which could be

considered as a precursor of the Venn diagram and concentric

circles models.

The rst step (1) in the quest for sustainability would be help to

equalize the importance and integrate the three aspects, where the

relative importance and impact of the economic aspects should be

equal to that of the environmental and social ones. In other words,

to pass from the conventional economics perspective to the integrational one. Two different trajectories are proposed depending on

the model used: Venn or concentric circles. To avoid further confusions, the morphology of the circles is used with the following

note of caution3: most of the literature does not state what the

circles represent. Usually they are referred to as aspects, dimensions or pillars. Do they represent economic, environmental

and social capitals? Or do they represent the impacts that each has

upon the other two? This author is inclined to believe that they

represent a difference between the capitals and the impacts that

the other circles have upon a particular circle. For example the

economic circle should be the sum of all the different economic

aspects, e.g. sales, prots, and revenues, among others, minus the

negative impacts the economic activities have, in the short- and

long-term, upon the natural environmental and social spheres.

Some examples negative impacts include natural disasters, epidemics, union strikes, corporate greeds deforestation of tropical

rainforests to replace them with mono-cultures, and the global

devastation created by the military industry that continues to

enrich some through fostering wars.

The rst trajectory is comprised of three steps. The rst step

(1Vd ) depicts the change towards more balanced inuence and

power of the three aspects, i.e. reducing that of the economic aspects while increasing those of the environmental and social aspects (Fig. 6). In the graphical representation this is reected by

making the circles have the same area. The aspects must be integrated to reect achievement of sustainability as the interaction

of the three, as in the Venn diagram (Fig. 1). The second step (2Vd )

is to further unite the three aspects (see Fig. 7) to reect that the

economic, environmental and social aspects are interacting. Once

this has been achieved, the circles need to continuously rotate so

that the different parts of each aspect are dynamic contact with all

the issues in the other two aspects. This means that each part is

inter-connected to others in the same and the other aspects (e.g.

carbon emissions are connected with energy which in turn is

connected to production, and so on). The further fusing of the

2

It should be noted that in many occasions the term development is used to

indicate economic growth, even though they are inherently different. The former

being improvements in well beings, quality of life and the environment, the latter

being an increase in GNP/GDP.

3

I would like to thank Prof. Peattie for making me reect upon this particular

topic. The reections have helped clarify many of my deep thoughts about the

circles and helped me to arrive at an interesting way of seeing their interactions.

1844

R. Lozano / Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

circles results in the First Tier Sustainability Equilibrium (FTSE), see

Fig. 8.

The second trajectory results from the concentric circles model.

It should be noted that Hart [18] proposed progressing from the

Venn diagram to the three concentric circles, but this shows little

interaction among the aspects and no longitudinal perspective. This

would indicate retrogression to a time in history where economic

activities had little impact on society and the environment, one that

does not represent the status of modern societies. It also does not

differentiate about economic activities that improve the environment or society and those which reduce them. In this trajectory the

economic aspects expand and inter-connect with the social subsystem, where the economic aspects are related to social ones

(1CC ) and go beyond economic theories that disregard the effect of

social aspects upon economic ones. In the graphical representation

this is equivalent to enlarging the economic circle and spinning it

continuously so that each of its parts is in contact with each of the

social aspects (Fig. 9). An example of this is prots, which are not

directly linked to personnel. Typically, in calculating prots, the

different costs are subtracted from revenues. One of the costs is that

of labour; a problem with this is that labour is just another part of

the equation and disregards motivation, culture and human needs

amongst others. In many cases employees are considered to be liabilities instead of assets [60].

Similarly, the social aspects, including the economic ones, expand and rotate in ways that interact with all dimensions of the

natural environment. As a result each aspect is interrelated with

every part of the other two aspects. In the representation this could

be viewed as only one circle, which is composed the dynamic interactions of all three primary dimensions. This creates the First Tier

Sustainability Equilibrium (FTSE), see Fig. 10.

As discussed, the Venn and concentric circles representations

lack the ability to show the dynamic time dimensions. They appear

only as snapshots, not fully representing sustainability. To address

this, the time perspective, also referred to as the inter-generational

aspect [3], is incorporated, into the three spinning circles. This

means moving from the integrational towards the inter-generational perspective. Fig. 11 shows an example of a prior attempt to

show this perspective. However, this does not show the interrelatedness of each aspect with the others, as in the case of the

Venn diagram.

Another representation aiming to include the time perspective

is offered by the Natural Step (TNS) framework [61], presented in

Fig. 12. The framework works in four phases: the rst phase,

awareness, involves aligning around a common understanding of

sustainability and the whole-systems context. The second phase,

baseline mapping, is designed to provide an analysis of todays

activities and how they relate to sustainability principles. The third

phase creates a vision of how a sustainable society would look like.

From this vision a strategy and action plans can be developed.

These are based on backcasting from principles. Phase 4 consists

of advising and supporting the execution of specic initiatives by

providing appropriate training, techniques, and tools for implementation, followed by measuring progress towards goals and

suggesting modications as needed [61,62]. The funnel provides

a comprehensive framework on how to move towards Sustainable

Societies through backcasting. However, as a representation, it does

not portray the interactions of economic, environmental and social

aspects. Furthermore, it implies that sustainability can be achieved,

while as previously mentioned, it is an ideal dynamic state.

A better way to graphically incorporate the time perspective is

to project the FTSE with no deviation through time, which would be

equivalent to exploding it into the third dimension (3D-Sust), thus

creating a perfect cylinder (Fig. 13). When there are deviations the

3D-Sust changes its shape from a cylinder to two types of cones.

The rst one is when too much emphasis is put on the present, e.g.

using discounting methods, and little or no attention is given to the

needs of tomorrow, then, instead of a cylinder, the shape takes the

form of a cone with its wider side in the present (Fig. 14). In an

extreme case this would make the 3D-Sust regress to the FTSE. The

second is when too much emphasis is put on the future but limited

emphasis is given to satisfying todays needs, then the cone would

have its wider base in the future.

The nal step involves the interactions of both equilibria into

a Two Tiered Sustainability Equilibria (TTSE). This is achieved by

inter-relating the FTSE in dynamic change processes through time,

passing from the inter-generational to the holistic perspective. In

this case the FTSE may not be the same today and in the future. In

the TTSE all aspects including the time perspective interrelate, for

example the economic aspects of today with the economic aspects

of the future, but also with the environmental aspects of the

present and the future, as well as with the social aspects of the

present and the future. These interactions occur with all the other

aspects of the present and the long-term, which make the cylinder

suffer a metamorphosis into a doughnut shape by imploding in the

direction of the time axis (Fig. 15), for this to occur time needs to

bend. In the TTSE sustainability issues lie inside the doughnut and

are in perennial movement inter-relating with other issues, continuously rotating in the two axes shown in the gure. This is aimed

at helping to represent sustainability more clearly and completely.

4. Conclusions

Modern ideologies that rely on short-term economic prots, and

scientic traditions based on reductionistic causeeffect relationships are failing to explain and address the complex dynamic inter-

Fig. 15. Two Tiered Sustainability Equilibria (TTSE). Interactions between the First Tier Sustainability Equilibrium, i.e. among economic, environmental, and social aspects; and the

Second Tier Sustainability Equilibrium, i.e. the short-, long- and longer-terms.

R. Lozano / Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

relations among economic, environmental, and social aspects and

the time perspective. The concepts of Sustainable Development

(SD) and sustainability have appeared as alternatives to help to

understand, address and reduce current, and potentially future,

economic disparities, environmental degradation, and social ailments. However, these concepts are still unfamiliar to, or are misunderstood by many individuals and societies worldwide. In order

to achieve real change it is necessary to facilitate greater awareness

and understanding within and throughout societies.

Although graphical representations, such as the Venn diagram,

concentric circles, and the Sustainability Hexagon, can help the

general public grasp the different aspects of SD and sustainability,

they suffer from several drawbacks, such as the depiction of sustainability as a steady state, a lack of full integration and interrelatedness amongst the different aspects, and a lack of

consideration of the dynamic time perspectives. These drawbacks

have been recognised by a number of sustainability scholars, researchers and practitioners, who have challenged their accuracy

and power to depict sustainability.

This author proposes a new way of depicting sustainability, the

Two Tiered Sustainability Equilibria (TTSE), where the issues in each

aspect (economic, environmental and social), interact with each

other, with issues in other aspects, and through time. The TTSE shows

the complex inter-linkages and inter-relations between the First and

Second Tier Sustainability Equilibria. It is hoped that the TTSE visual

model will help people to more effectively understand that in order

for us to achieve societal sustainability we must use holistic, continuous and interrelated phenomena amongst economic, environmental, and social aspects, and that each of our decisions has

implications for all of the aspects today and in the future. This author

welcomes your feedback and suggestions for further improvements.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Miss Frances Hines, Prof.

Don Huisingh, Prof. Francisco Lozano and Prof. Ken Peattie for their

critiques and comments, and excellent recommendations for ways

to improve this document.

References

[1] Carley M, Christie I. Managing sustainable development. 2nd ed. London:

Earthscan Publications Ltd; 2000. p. 322.

[2] Dalal-Clayton B, Bass S. Sustainable development strategies. 1st ed. London:

Earthscan Publications Ltd; 2002. p. 358.

[3] WCED. Our common future. 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1987.

[4] Korten DC. When corporations rule the world. 2nd ed. Bloomeld,

Connecticut: Kumarian Press Inc.; 2001.

[5] Cairns Jr J. Will the real sustainability concept please stand up? Ethics in

Science and Environmental Politics 2004:4952.

[6] Reid D. Sustainable development. An introductory guide. 1st ed. London:

Earthscan Publications Ltd; 1995. p. 254.

[7] Roorda N. AISHE: auditing instrument for sustainable higher education. Dutch

Committee for Sustainable Higher Education; 2001.

[8] Rosner WJ. Mental models for sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production

1995;3(12):10721.

[9] Senge PM. The fth discipline. The art & practice of the learning organization.

London: Random House Business Books; 1999.

[10] Dresner S. The principles of sustainability. 1st ed. London: Earthscan

Publications Ltd; 2002. p. 200.

[11] Kirkby J, OKeefe P, Timberlake L. The Earthscan reader in sustainable

development. 1st ed. London: Earthscan Publications Ltd; 1995. p. 371.

[12] Atkinson G. Measuring corporate sustainability. Journal of Environmental

Planning and Management 2000;43(2):23552.

[13] Costanza R. Ecological economics. The science and management of

sustainability. New York: Columbia University Press; 1991. p. 525.

[14] Currie-Alder B. Barriers to sustainability: problems inhibiting the success of

SANREM-Ecuador; 1997.

[15] Dobers P, Wolff R. Competing with soft issues from managing the

environment to sustainable business strategies. Business Strategy and the

Environment 2000;9:14350.

[16] Doppelt B. Leading change toward sustainability. A change-management guide

for business, government and civil society. Shefeld: Greenleaf Publishing; 2003.

1845

[17] Fadeeva Z. Promise of sustainability collaborationpotential fullled? Journal

of Cleaner Production 2004;13:16574.

[18] Hart M. A better view of a sustainable community [Web-page] [accessed 07.12.

05]. Available from: http://www.sustainablemeasures.com/Sustainability/

ABetterView.html; 2000.

[19] Miller GT. Living in the environment. 12th ed. Belmont, California: Thomson

Learning, Inc; 2002.

[20] Rees WE. An ecological economics perspective on sustainability and prospects

for ending poverty. Population and Environment 2002;24(1):1546.

[21] Reinhardt F. Sustainability and the rm. Interfaces 2000;30(3):2641.

[22] Goldin I, Winters LA, editors. The economics of sustainable development.

OECD Cambridge University Press; 1995.

[23] Stavins RN, Wagner AF, Wagner G. Interpreting sustainability in economic

terms: dynamic efciency plus intergenerational equity. Economic Letters

2003;79:33943.

[24] Lozano R. Developing collaborative and sustainable organisations. Journal of

Cleaner Production 2008;16(4):499509.

[25] Bartelmus P. Sustainable development paradigm or paranoia?. Wuppertal

Institute; 1999.

[26] Mishan EJ. Evaluation of life and limb: a theoretical approach. The Journal of

Political Economy 1971;79(4):687705.

[27] Daly HE. Sustainable development: denitions, principles, policies.

Washington, DC: World Bank; 2002.

[28] Fullan M. The change leader. Educational Leadership 2002:1620.

[29] Hart S. Beyond greening: strategies for a sustainable world. Harvard Business

Review 2000:6676.

[30] Langer ME, Schon A. Enhancing corporate sustainability. A framework

based

evaluation

tools

for

sustainable

development.

Vienna:

Forschungsschwerpunkt

Nachhaltigkeit

und

Umweltmanagement,

Wirtschaftsuniversitat Wien; 2003.

[31] Murcott S, Appendix A. Denitions of sustainable development [webpage]

[accessed 19.06.03]. Available from: http://www.sustainableliving.org/appena.htm; 1997.

[32] Reinhardt F. Sustainability and the rm. Zurich: University of Zurich; 2004.

[33] Diesendorf M. Sustainability and sustainable development. In: Dunphy D,

Benveniste J, Grifths A, Sutton P, editors. Sustainability: the corporate

challenge of the 21st century. Sydney: Allen & Unwin; 2000. p. 1937.

[34] Salzmann O, Ionescu-Somers A, Steger U. The business case for corporate

sustainability review of the literature and research options. IMS/CSM;

2003.

[35] Elkington J. Cannibals with forks. Oxford: Capstone Publishing Limited; 2002.

[36] Hodge RA, Hardi P, Bell DVJ. Seeing change through the lens of sustainability. Costar Rica: The International Institute for Sustainable Development;

1999.

[37] Hussey DM, Kirsop PL, Meissen RE. Global reporting initiative guidelines: an

evaluation of sustainable development metrics for industry. Environmental

Quality Management 2001:120.

[38] Bhaskar V, Glyn A. The north the south and the environment. Ecological

constraints and the global economy. 1st ed. London: Earthscan Publications

Limited; 1995. p. 263.

[39] Elsen A. Sustainable development research at the University of Amsterdam.

Amsterdam: United Nations Environment Programme; 1998. p. 64.

[40] Lozano-Ros R. Sustainable development in higher education. Incorporation,

assessment and reporting of sustainable development in higher education

institutions, in IIIEE. Lund: Lund University; 2003.

[41] Lozano R. Collaboration as a pathway for sustainability. Sustainable

Development 2007;16(6):37081.

[42] Martin S. Sustainability, systems thinking and professional practice.

Worcester: University College, Worcester; 2003.

[43] Schnotz W. Towards an integrated view of learning from text and visual

displays. Educational Psychology Review 2002;14(1):10120.

[44] Carney RN, Levin JR. Pictorial illustrations still improve students learning

from text. Educational Psychology Review 2002;14(1):526.

[45] Hilligoss S, Howard T. Visual communication a writers guide. 2nd ed. New

York: Longman; 2002.

[46] Stokes S. Visual literacy in teaching and learning: a literature review.

Electronic Journal for the Integration of Technology in Education 2001;1(1).

[47] Sankey M. Visual and multiple representations in learning materials: an issue

of literacy. University of Southern Queensland; 2003.

[48] Mitchell C. Integrating sustainability in chemical engineering practice and

education. Transactions of the Institution for Chemical Engineering 2000;

78(B):23742.

[49] Mebratu D. Sustainability and sustainable development: historical and

conceptual review. Environmental Impact Assessment Review 1998;18:493520.

[50] Peattie K. Environmental marketing management. Meeting the green

challenge. London: Financial Times. Pitman Publishing; 1995.

[51] Benson DE. Move ahead with the past for wildlife and nature conservation. In:

Transactions of the 2002 North American Wildlife and Natural Resources

Conference Washington, DC; 2002. p. 16177.

[52] Benson DE, Darracq EG. Integrating multiple contexts for environmental

education. In: Field R, Field R, Warren RJ, Okarma H, Seivert PR, editors.

Wildlife, land, and people: priorities for the 21st century. Proceedings of the

second international wildlife management congress. Godollo, Hungary: The

Wildlife Society, Bethesda, Maryland, USA; 2001.

[53] Hart S. Beyond greening: strategies for a sustainable world. Harvard Business

Review 1997;75(1):6676.

1846

R. Lozano / Journal of Cleaner Production 16 (2008) 18381846

[54] Dyllick T, Hockerts K. Beyond the business case for corporate sustainability.

Business Strategy and the Environment 2002;11:13041.

[55] Ehrenfeld JR. Eco-efciency. Philosophy, theory, and tools. Journal of Industrial

Ecology 2005;9(4):68.

[56] Henriques A, Richardson J, editors. The triple bottom line. Does it all add up?

London: Earthscan; 2005.

[57] Durphy D, Grifths A, Benn S. Organizational change for corporate

sustainability. London: Routledge; 2003.

[58] Micklin PP. The Aral Sea problem. Proceedings of ICE Civil-Engineering 1994;

102:11421.

[59] Waltham T, Sholji I. The demise of the Aral Sea an environmental disaster.

Geology Today 2001;17(6):21824.

[60] Drucker P. Theyre not employees, Theyre People. Harvard Business Review

2002:717.

[61] Robert K-H. Tools and concepts for sustainable development, how do they

relate to a general framework for sustainable development, and to each other?

Journal of Cleaner Production 2000;8:24354.

[62] The Natural Step New Zealand. The Natural Step Framework [accessed 15.02.

08]. Available from: Implementation methodology http://www.naturalstep.

org.nz/tns-f-implementation.asp 2007.

You might also like

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Deep Dive On Vector Autoregression in R by Justin Eloriaga Towards Data ScienceDocument18 pagesA Deep Dive On Vector Autoregression in R by Justin Eloriaga Towards Data Scienceante mitarNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Chapter 4 CB Problems - FDocument11 pagesChapter 4 CB Problems - FAkshat SinghNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Case 4 - Curled MetalDocument4 pagesCase 4 - Curled MetalSravya DoppaniNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Handout 2Document2 pagesHandout 2altynkelimberdiyevaNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- How I Found Freedom in An Unfree WorldDocument11 pagesHow I Found Freedom in An Unfree WorldGustavo PraNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Strategic Management of Southeast Bank LimitedDocument32 pagesStrategic Management of Southeast Bank LimitediqbalNo ratings yet

- IB Economics Markscheme for Monopolistic Competition vs MonopolyDocument17 pagesIB Economics Markscheme for Monopolistic Competition vs Monopolynikosx73No ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Professional Knowledge Questions For IBPS SO Marketing Mains 2017 4Document2 pagesProfessional Knowledge Questions For IBPS SO Marketing Mains 2017 4Arif MohammadNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Case Study Plant RelocationDocument5 pagesCase Study Plant Relocationviren gupta100% (1)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Introduction To Economic Test CHPT 9,10 &14.docx NEWDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Economic Test CHPT 9,10 &14.docx NEWAmir ContrerasNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- Chapter 1 SolutionDocument2 pagesChapter 1 SolutionRicha Joshi100% (1)

- FBO Unit 1Document62 pagesFBO Unit 1Abin VargheseNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- PS5 ECO101 PS5 Elasticity Part2 SolutionsDocument6 pagesPS5 ECO101 PS5 Elasticity Part2 SolutionsAlamin Ismail 2222905630No ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Rural Development PlanningDocument16 pagesRural Development PlanningParag ShrivastavaNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Inflation Chapter SummaryDocument14 pagesInflation Chapter SummaryMuhammed Ali ÜlkerNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Man Eco 3Document3 pagesMan Eco 3James Angelo AragoNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Finance FormulaDocument5 pagesFinance FormulaRanin, Manilac Melissa S100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Debt Relief: A Time For Forgiveness: by Martin SandbuDocument5 pagesDebt Relief: A Time For Forgiveness: by Martin SandbuSimply Debt SolutionsNo ratings yet

- Balance of PaymentsDocument17 pagesBalance of PaymentsBhavya SharmaNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 4 Risk and Return The BasicsDocument48 pagesCHAPTER 4 Risk and Return The BasicsBerto UsmanNo ratings yet

- Brian Walters and Associates: Business Valuation/ Management Consulting ServicesDocument28 pagesBrian Walters and Associates: Business Valuation/ Management Consulting Servicesbvwalters322No ratings yet

- David Kreps-Gramsci and Foucault - A Reassessment-Ashgate (2015)Document210 pagesDavid Kreps-Gramsci and Foucault - A Reassessment-Ashgate (2015)Roc SolàNo ratings yet

- Soscipi-PPT5 VebienDocument6 pagesSoscipi-PPT5 VebienDKY SYSNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Meaning and Concept of Capital MarketDocument11 pagesMeaning and Concept of Capital Marketmanyasingh100% (1)

- SFM Volume 2Document193 pagesSFM Volume 2Joy Krishna DasNo ratings yet

- Saudi Arabia EconomicsDocument14 pagesSaudi Arabia Economicsahmadia20No ratings yet

- Chapter 1 - Introduction To Strategic ManagementDocument39 pagesChapter 1 - Introduction To Strategic ManagementMuthukumar Veerappan100% (1)

- Solution Manual For Economics For Today 10th Edition Irvin B TuckerDocument6 pagesSolution Manual For Economics For Today 10th Edition Irvin B TuckerRuben Scott100% (35)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Measuring The Cost of Living: Mæling FramfærslukostnaðarDocument23 pagesMeasuring The Cost of Living: Mæling FramfærslukostnaðarSharra Kae MagtibayNo ratings yet

- UET Fee Challan TitleDocument1 pageUET Fee Challan Titlemubarakuet225No ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)