Professional Documents

Culture Documents

1930 WALEY Notes On Chinese Alchemy

Uploaded by

DannieCaesarOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

1930 WALEY Notes On Chinese Alchemy

Uploaded by

DannieCaesarCopyright:

Available Formats

Notes on Chinese Alchemy ("Supplementary to Johnson's" A Study of Chinese Alchemy)

Author(s): A. Waley

Source: Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, Vol. 6, No. 1 (1930),

pp. 1-24

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the School of Oriental and African Studies

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/607294 .

Accessed: 10/01/2015 10:08

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Cambridge University Press and School of Oriental and African Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to

digitize, preserve and extend access to Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, University of London.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ULLETIN

OF THE

SCHOOLOF ORIENTALSTUDIES

LONDONINSTITUTION

PAPERS

CONTRIBUTED

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

(Supplementaryto Johnson's A Study of Chinese Alchemy)

By A. WALEY

when it has been made the subject

ALCHEMY, on the rare occasions

of reasonable inquiry, has usually been studied as part of what

one may call the pre-history of science. But if, to use a favourite

phrase, we are to see in alchemy merely " the cradle of chemistry ",

are we not likely, whatever its initial charm, to lose patience with

an infancy protracted through some fifteen centuries ?

It is certain in any case that another aspect of alchemy-its

interest as a branch of cultural history-has hitherto been strangely

neglected. Mr. Walter Scott, for example, omits alchemistic writings

from his great edition of the Hermetica on the odd ground that they

are merely " masses of rubbish ". But if texts are to be dismissed

as rubbish because they contain beliefs that we cannot share, I see

no reason why the religious and philosophical parts of the Hermetica

(and with them many books which to-day enjoy a far wider popularity)

should- continue to claim attention. It is a curious fact that

if alchemists had been cannibals, instead of civilized town-dwellers,

no one at the present day would venture to question the interest

and importance of studying their doctrines. For it seems to have been

decided that the true anthropology, the " proper study of mankind ",

is uncivilized man. The reason for this is clear, and in general

I.

1

VOL.VI. PART

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. WALEY-

adequate. So soon as we reach in the history of the human mind

a point where it begins to establish contact with our own ways of

thought, objectivity must to some extent begin to recede. For

example, no writer has succeeded in viewing minds even so remote

from us as those of the early Christian Fathers with the scientific

detachment of an anthropologist discussing, say, the religious beliefs

of a Melanesian. Fortunately, the Chinese occupy, in this respect,

a rather unusual position. Owing to their remoteness and the absence

of traditions common with our own, we can follow their mental history

with some degree of detachment to a point far beyond what would

be possible in Europe. We can apply the methods of anthropology

to civilized man, and so at least in one portion of mankind view in

continuity processes that in the West are disjointed by our own

irony or sympathy. Moreover, in China the continuity is actually

far greater than in our own world. The great Aryan invasions that

in Europe, the Near East, and India, set a barrier between history

and pre-history did not affect China at any rate in such a way as

markedly to dissociate her from her past.1 More than any other

creators of culture, the Chinese remained in contact with Neolithic

mentality, and it is possible in China to see in their proper setting

and consequently to understand ideas and customs that elsewhere

appear arbitrary and disconnected.

Such, as I shall show,2 seems to me to be the case with alchemy.

The subject, particularly at its outset, is a very complicated one,

and I have therefore thought it better to present these notes in a

rather schematic form. Here is the first text :1. Han Shu xxv, 12 recto, line 8.

[The wizard Li] Shao-chiin said to the Emperor [Wu Ti of Han]:

'' Sacrifice to the stove [I tsao] and you will be able to summon

' things ' [i.e. spirits]. Summon spirits and you will be able to change

cinnabar powder into yellow gold. With this yellow gold you may

make vessels to eat and drink out of. You will then increase your

span of life. Having increased your span of life, you will be able to

see the hsien J4 of P'6ng-lai that is in the midst of the sea. Then

you may perform the sacrificesfing and shan, and escape death."

That the Aryans reaohed the western fringe of China is, of course, established.

Whether they penetrated into the interior and whether any of China's early enemies

were Aryans is still uncertain.

2 See

particularly p. 18.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

Comment

the

Date

(a)

Passage

of

This passage also occurs in the History of Ssu-ma Ch'ien (Treatise

on the SacrificesFang and Shan, Bk. xxvrii, Chavannes, vol. iii, pt. ii,

p. 465).1 But this treatise of Ssu-ma Ch'ien is almost certainly

a late addition to the text. We know that even by the first century

A.D. many of the original chapters had been lost. What now poses

as the Treatise on Fang and Shan, though it contains some information

on this subject, is in reality an account of religion in general. Almost

the whole of the treatise occurs practically verbatim in the account

of Worship and Sacrifice, Z j -~-, which forms chap. xxv of the

Han Shu. The bulk of the treatise is irrelevant to Ssu-ma Ch'ien's

purpose, but perfectly appropriate to an account of Worship and

Sacrifice.

It is safer, therefore, to regard this passage, the earliest reference

to alchemy in any literature,2 as belonging to the first century A.D.

rather than the first century B.c.

(b) Literary Form of the Passage

The passage is one of those rhetorical catenceof which early Chinese

writers are so fond. They have been discussed by Masson-Oursel

and Maspero. Their intention is dramatic rather than logical. Such

logical connections as exist are implied rather than expressed. The

most difficult step to follow is the statement: " Having increased

your span of life, you will be able to see ... hsien." It implies, perhaps,

a theory that hsien (Immortals) are only visible to those whose span

of life at any rate makes some 'approach to their own. The whole

process leads up to the performance of the sacrifices Feng and Shan,

through which the Emperor will obtain immortality. Alchemy,

then, is here regarded as the third in a series of performances, which

lead ultimately to an Emperor becoming immortal. Viewed in this

light alchemy does not concern people in general, but only the

Emperor. It would, however, be pedantic to interpret logically

a passage that is essentially rhetorical.

1 The

Ssu-ma Ch'ien passage is identical with the Han Shu from f. 3 verso to

f. 32 recto of chap. xxviii.

2

Leaving aside the texts published by R. Campbell Thompson in his The

Chemistry of the Ancient Assyrians, Luzac, 1925. These do not deal with the

manufacture of gold nor of an elixir of life.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. WALEY-

(c) Characterof the Passage in its Bearing on Alchemy

Those familiar with the literature of Chinese alchemy will admit

that this passage is curiously isolated. The idea that drinking from

vessels of alchemic gold is a way of increasing longevity is, however,

not unknown to the later literature. Pao P'u Tzu (iv, 17 recto, 1. 2)

says: "If with this alchemical gold you make dishes and bowls,

and eat and drink out of them, you shall live long." It was indeed

j P

accepted that artificial gold . #

g A " was superior to

the natural." 1 But the " increase in longevity" is in all later

literature regarded as an end in itself, attainable by ordinary people,

and not merely as a means by which the Emperor might become

immortal.

2. The Story of Ch'?ng Wei, from Huan T'an's Hsin Lun 2

There was once a courtier of the Han dynasty, named Ch'?ng Wei

f~* , who was fond of the Yellow and White Art. His wife was

the daughter of a magician. He was often obliged to follow the

Emperor's chariot, but had no seasonable clothing. This very much

vexed him. His wife said: "I will ask Lthe spirits] to send two

strips of strong silk." Whereupon the strong silk appeared in front

of him with no apparent reason. Ch'EngWei.tried to make gold &

"Vast treasure in

according to the directions of the ~

the Pillow." He was unsuccessful, and his wife, going to look at him,

found him just fanning the ashes in order to heat the retort. In

the retort was some quicksilver. She said: " Just let me see what

I can do," and from her pocket produced a drug, a small quantity

of which she threw into the retort. A very short while afterwards

she took the retort out (of the furnace), and there was solid silver all

complete ! [The husband then pesters her to teach him the secret,

but she refuses to do so and finally, worried into madness, she rushes

into the street, smears herself with mud, and shortly afterwards

expires.]

1 Pao P'u Tzu, xvi, 6 recto, 1. 1. For Pao P'u Tzu (the pseudonym of Ko Hung),

fourth century A.D., see below, p. 9. The name is often wrongly written " Pao P'o

Tzu ". The character f

is, however, only pronounced P'o when it means a

nettle-tree.

2 Save for a series of

quotations in the Ch'iln Shu Yao Chih, the book is lost.

The story is quoted by Pao P'u Tzu (xvi, 3 verso, 1. 1), who merely introduces it

with the words

" Huan Chiin-shan [i.e., Huan T'an

says "

from Huan

But on the next page a similar anecdote is specifically quoted as being -)

Tan's Hsin Ch'ilan V T

, which is evidently the sam as the Hsin Lun AJ

-.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

Commenton the Story of Ch'eng Wei

Huan T'an, from whose book this story is quoted, died c. A.D. 25,

aged about 70. Of Ch'?ng Wei himself nothing further is known;

but there seems to be no reason to doubt that such a person lived

in the first century B.c. or earlier, and was addicted to alchemic

experiments. Thus we may assume that alchemy existed under the

Han dynasty 1; but the literature of the period is surprisingly silent

on the subject. Wang Ch'ung in his Lun Heng 2 denounces a vast

number of other Taoist credulities. It is hard to believe that if

alchemy had been at all prominent he would not have singled it out

for attack.

Other Han literature (Huai Nan Tzu, for example) is equally silent.3

But I emphasize the silence of Wang Ch'ung because it was against

just such practices that his book was directed.

There seems no reason to doubt (as we shall see presently) that

in the second and third centuries alchemy was already under full way.

But the biographies of famous magicians and recluses who lived at

this period say nothing about it. For example, in the official

biographies of Hsi K'ang, V ) (A.D. 223-62, Chin Shu xlix, 8;

San Kuo Chih xxi, 4), there is no mention of alchemy, nor does Hsi

K'ang refer to it in his surviving works. Yet it is as an alchemist

that he figures in popular tradition.

3. The Ts'an T'ung Ch'i & [ i~

(a) Nature of the Work

This, the most popular of all alchemic books, consists of ninety

paragraphs (the division, like that of Lao Tzu's Tao Th Ching, was

made for convenience by a late editor) partly in prose, partly in verse

of five, or more often four, words to the line. It is, essentially, an

to the

application of the cosmic doctrines of the I Ching Y.

principles of alchemy. But the alchemical processes are alluded to

in veiled language, and a person unfamiliar with alchemic literature

might easily suppose that the book dealt with the theories of the

I Ching.

1 In pre-Han literature there are no references to alchemy.

2 Middle of the first century A.D.

Translated by Forke.

3 In his surviving works; but possibly he said something about the subject in

his lost Chung Pien which dealt with WI~(II (i.e. Taoist divinities and adepts) and

S~3 (gold and silver; i.e. the art of making gold and silver ?).

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. WALEY-

(b) The Title

Ts'an T'ung Ch'i means something like " Union of Compared

Correspondences". Concerning what these correspondences are,

there exist several theories: (a) A series of correspondences between

the principles of the I Ching and those of alchemy; (b) A series of

correspondences between the processes by which the world came into

existence, and the process by which the Elixir comes into existence;

(c) Ts'an means strictly "a comparison of three things ". These

three things, according to a work 1 of c. A.D. 1,000, are lead, mercury,

and sulphur, all of which can be reduced to the same prime substance

and are therefore essentially identical.

(c) The Author

The book is attributed to a certain Wei Po-yang Vg

W or

of

Wei

is

This

a

" Po-yang

".

clearly pseudonym.

Po-yang is the " style " of Lao Tzu, and it is clear that there has

been some confusion between the legend of Lao Tzu and that of

Wei Po-yang. Pao P'u Tzu (iii, 6 recto, 1. 9) says: 4 g

j~

"No

one

ever

ft: 0 A

got

1 I

. &A

T 9

"

.- He had a son named Tsung, who served

higher tao than Po-yang.

the Wei State and became a general."

It is clear that Pao P'u Tzu is not here talking of Lao Tzu (whom

he calls Lao, Lao Tzu, Lao Chiin, etc.), but of someone less well known.

But Lao Tzu had, according to Ssu-ma Ch'ien, " a son named Tsung."

Moreover, Pao P'u Tzu elsewhere (viii, f. 1 verso, 1. 4) mentions

Po-yang as a " keeper of archives ". Here again, although there is

obvious confusion with Lao Tzu, who was also an archivist, I do not

think that Pao P'u Tzu is speaking of Lao Tzu himself.

The author of the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i, however, is generally considered

to have flourished c. A.D. 120-50. If we accept this, we must suppose

that he took as his pseudonym the name of an ancient sage, a sort

of counterpart of Lao Tzu, called Po-yang of the Wei State, in contradistinction to Lao Tzu, who was Po-yang of the Chou State. A confusion between Po-yang, the ancient sage and Po-yang, author of

the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i seems to me also to exist in Ko Hung's Shin

Hsien Chuan,2 which gives the longest extant account of Po-yang.

1 The Yan Chi Ch'i Ch'ien -P.

L 1, chap. 690. This series of Taoist

text is No. 1020 in Wieger's index to the Taoist Canon.

2 This book is several times quoted in P'ei

Sung-chih's

commentary

_

on the San Kuo Chih (preface dated 429 A.D.). The quotations

correspond with the

book as it now exists. With regard to its authorship, see below.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

It is clear from the position in which Ko Hung places Wei Po-yang

that he regards him as an " ancient sage ", not as a personage of the

Latter Han dynasty; for he puts him in an initial chapter, the other

subjects of which are Kuang-ch'?ng Tzu (wholly mythical; contemporary with the Yellow Emperor), Lao Tzu and P'Eng Tsu the

Chinese Methusalah, who " at the end of the Yin dynasty was already

767 years old ". Wei Po-yang, says the Shin Hsien Chuan, was a

man of Wu; and after a long anecdote which will be found in Giles's

Biographical Dictionary and does not here concern us, there follows

this information: "Po-yang made the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i and the

Wu-hsing hsiang-lei (' That the Five Elements have an [underlying]

similarity')' in three chapters. Verbally they concern the Book of

Changes, but in point of fact they use the symbols of the Book of

Changes as a cover for the discussion of alchemy, 4 ) 1-. But

ordinary Confucians, knowing nothing of alchemy, have commented

on the book as though it were a treatise on Yin and Yang (the male

and female principle), and in this way completely misunderstood it."

Despite the fact that Ko Hung (reputed author of the Shin Hsien

Chuan) certainly regards Wei Po-yang as a sage of remote and shadowy

times, he gives a very true and sensible description of the Ts'an T'ung

Ch'i which was (according to the usual hypothesis) in reality written

by the second century author who used Wei Po-yang as his pseudonym.

One of the " ordinary Confucians" who, not understanding

alchemy, mistook the work for a discussion of the Book of Changes,

seemed to have been Yii Fan, b%R (A.D. 164-233); for in the Ching

Tien Shih Win 2 (" Textual Criticism of the Classics ") by Lu T?-ming,

in the section on the Book of Changes with which the work begins,

we find: b Ni t

*- p M

J&-

y "Yii Fan

in his commentary on the Ts'an- T'ung Ch'i says, 'The character I

3

(Changes)is composed of Sun above Moon.' "

The book is therefore referred to by Yii Fan about A.D. 230, and

by Ko Hung c. A.D. 320. Henceforward it is mentioned fairly

frequently. For example, in the poems of Chiang Yen * (end of

the fifth century) :This is an alternative name for chap. iii of the book.

About A.D. 600. I owe this reference to Dr. Hu Shih.

3 This passage is capable of various interpretations. No commentary by Yii Fan

on the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i survives. We might punctuate " Yfi Fan [says] the commentary on the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i says . . ." But for our purposes the result remains

the same: the existence of the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i is already referred to early in the

third century.

4

, chap. iii of 5 verso. Ssil Pu Ts'ung K'an edition.

J1

3 3

1

2

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

A. WALEY-TEXT

" He proved the truth of the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i;

In a golden furnace he melted the Holy Drug."

In the next (the sixth) century, there is a curious hiatus. The

book is not mentioned in the bibliography (chap. xxxiv) of the History

of the Sui Dynasty. Possibly the author meant to put it in as a treatise

on the Five Elements, but realized that this was a mistake, without

however, remembering to repair his error by entering it among Taoist

books. It duly appears, however, in the bibliography of the old

T'ang History as-

A

gl

A [J

Chapter2.

Chapter 1.

~

TL

" The Ts'an T'ung Ch'i of the Chou dynasty Book of Changes";

The

Five Elements Resembling one Another of the Chou dynasty

"

Book of Changes."

As the heading of the titles implies, the work is here accepted

as a study of the Book of Changes, and it is catalogued as a treatise

on the Five Elements. Finally, in the tenth century it was divided

into ninety sections or paragraphs and commented upon by P'Yng

Hsiao Z~-.1

(d) The Style of the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i

Attempts are sometimes made to date texts of this kind by the

rhyme-system used in verse portions. This is dangerous. We know,

for example, that in the T'ang dynasty at least three rhyme systems

were used concurrently: (1) an intentionally archaic one with an

approximation to the rhymes of the Book of Odes; used in eulogies,

etc., written in four-syllable verse; (2) the rhymes of " Old Poetry "

, songs, etc.; (3) the strict rhyme-system of the T'ang dynasty.

tThe opinion of the great Chu Hsi (1130-1200) upon the Ts'an T'ung

Ch'i has often been

j

quoted": , p

.. [?

" The Ts'an T'ung Ch'i is from the literary point of view very well

written and would actually seem to be by some capable writer of the

1 Taoist Canon, Wieger No. 993.

2 Chu

Tzu Yu Lei, Bk. 125.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTESON CHINESEALCHEMY

Latter Han period. It contains frequent allusions to ancient books,

and these make it hard for a modern reader to understand."

It is very difficult to know how much value should be attached to

this judgment. Chu Hsi was not primarily a literary critic or historian

of style. Again, Liu Chan-wing I

%

,1 more of a specialist

"

~A [~

in these matters,

Pil

3 "Of

I

says":

old books only the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i has a style resembling that of

pre-Ch'in works." It is not clear whether Liu actually means to

imply that the book is a Chou Dynasty work, or merely that it is

a successful imitation of Chou style. Against these two views may

be set that of the Catalogue of Ch'ien Lung's Four Libraries, which

for very inadequate reasons places the book at the end of T'ang.

At the present point in our inquiry there seems no reason to doubt

that the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i we now possess was written under the

pseudonym Wei Po-yang, in the second century A.D.

But certain difficulties arise when we discuss the next great figure

in the history of Chinese alchemy:4. Pao P'u Tzu

(a) This is the pseudonym of Ko Hung (c. A.D. 260-340), and it is

by this name that his principal book is known. It is divided into

two parts. The " exoteric ", which deals with Confucian topics,

does not here concern us. The esoteric contains, besides scattered

references to alchemy, a whole book (chap. iv) devoted to the

Philosopher's Stone 2 yf-, and another book (part of chap. xvi)

dealing with the manufacture of gold and silver. But before discussing

the contents of Ko Hung's book we must deal with its bearing on the

problem of the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i.

(b) Pao P'u Tzu and the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i

In Pao P'u Tzu the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i is never mentioned. This

a

is singular fact. As we have seen, Ko Hung knows Wei Po-yang,

the supposed author of the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i, as an " ancient sage ".

In the list of Taoist works at the end of Pao P'u Tzu (recording over

eighty volumes; the earliest bibliography of this kind) Ko Hung

" Inner Book " of Wei

(xix, 4 verso) mentions a Nei Ching N

V., Nor is the latter ever

Po-yang but not the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i.

mentioned throughout the book.

1

End of thirteenth century, quoted in Taoist Canon, Wieger, No. 990, preface.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

10

A. WALEY---

This brings us back to the Shin Hsien Chuan,' which work purports

to be by the same author as Pao P'u Tzu. In the preface to the

Shjn Hsien Chuan Ko Hung says that he wrote it after composing

the esoteric chapters NJ t of Pao P'u Tzu. At the end of the

exoteric chapters (1, f. 10 verso, 1. 9) is an autobiography, the

fullest document of this kind that early China produced. Here Ko

Hung mentions as one of his works a Shen Hsien Chuanin ten chapters.

It has been pointed out as an inconsistency that in the preface to the

Shin Hsien Chuan Ko Hung should say that he wrote it later than

Pao P'u Tzu; while in Pao P'u Tzu the Shin Hsien Chuan is already

mentioned. A simple solution would be to suppose that Ko Hung

wrote first the esoteric chapters, then the Sh&n Hsien Chuan and

then the exoteric chapters.

If we accept that Ko Hung is actually author of both works,

we shall have to assume that at the time he wrote the Esoteric

chapters he was unacquainted with the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i; whereas

when he wrote the Shen Hsien Chuan he had at last become familiar

with it.

But did Ko Hung really write the Shin Hsien Chuan ? If we

confront similar passages from it and from the undoubtedly authentic

Pao P'u Tzu it becomes hard to believe that both are by the same

hand. Take the story of Ch'6ng Wei, quoted above.2 Not only is

the style strangely different, but the Shen Hsien Chuan version is

so meagre and so incompetently told that one doubts whether the

author of it is even trying to pass himself off as Ko Hung.

It seems indeed likely that the Shin Hsien Chuan, though a work

of the fourth century, was merely an anonymous series of Taoist

biographies, which some mistaken person labelled as Ko Hung's

Shin Hsien Chuan and divided into ten chapters.

But Ko Hung's ignorance of the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i still remains

inexplicable.

It would, of course, be an anachronism to expect in an ancient

Chinese author the same bibliographical completeness that we demand

in a modern scholar. But that a writer so encyclopeedicshould ignore

a work of such importance, dealing with a subject in which he was an

hereditary specialist,3 is difficult to believe. It becomes necessary,

1

Biographies of Taoist divinities and adepts.

Shin Hsien Chuan, vii. Biography No. 3.

3 For the line of succession by which Ko Hung claimed to inherit his alchemistic

knowledge, see below, p. 12.

2

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

11

therefore, to consider whether it is certain that Yii Fan, writing in the

third century, really refers to the Ts'an T'ung Ch'i as we know the

book to-day. Is it not possible that the work was originally an

exposition of the Book of Changes and that some time after Pao P'u

Tzu and before the Shin Hsien Chuan (say, in the latter part of the

fourth century) someone doctored the text so as to make it serve as a

work on alchemy ? The actual number of insertions necessary for this

purpose would have been very small. The first third of the work is

purely cosmological. References to the firing of metal in a furnace

are not necessarily concerned with alchemy; the principle that " fire

conquers metal " belongs to the speculations of the cosmologists

(_WI T

), as does the identification of the five metals with the

five planets. The only one of the 90 sections which is clearly and

indubitably concerned with the Elixir is the thirty-second :If even the herb chii-sheng JI ) can make one live longer,

Why not try putting the Elixir g f 1 into the mouth ?

Gold (,) by nature does not rot or decay;

Therefore it is of all things most precious.

When the artist 4f1??L(i.e. alchemist) includes it in his diet

The duration of his life becomes everlasting . . .2

When the golden powder enters the five entrails,

A fog is dispelled, like rain-clouds scattered by wind.

Fragrant exhalations pervade the four limbs;

The countenance beams with well-being and joy.

Hairs that were white all turn to black;

Teeth that had fallen grow in their former place.

The old dotard is again a lusty youth;

The decrepit crone is again a yoAng girl.

He whose form is changed and has escaped the perils of life,

Has for his title the name of True 3 Man.

Apart from this paragraph, the number of passages that are

incapable of interpretation except as disquisitions on alchemy is very

small.

1 The huan tan or " returned cinnabar" is the cinnabar that by the process of

alchemy has been " returned " or restored to its first nature.

2

I omit a couplet which does not occur in all versions of the text, and seems

irrelevant.

3 "

True," of course, in the sense of purified, freed from dross. Metals subjected

to the purifying processes of alchemy also become " true ".

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

12

A. WALEY-

(c) Ko Hung's Line of Transmission

Ko Hung claims to have received the secrets of alchemy from a

*

M

certain Chang Yifi

. Chang Yin learnt from Ko Hsiian 1,

Ko Hung's great-uncle. Finally, Ko Hsiian learnt from Tso Tz'u,

AI a,1I about A.D. 220. It is at this point that, mundanely speaking,

the line of transmission begins. For Tso Tz'u received his initiation,

in the early years of the third century, from a " deity " j" A. To

Ko Hung's great-uncle Tso Tz'u passed on three books: The Alchemy

j )j- @, T

Book of the Great Clear One

The Alchemy Book of the

J a .

Nine Tripods, and The Gold Juice 2 Alchemy Book

- and

(d) The distinction betweenChin Tan ,Ik tj

Huang Po

The fourth book of the esoteric chapters of Pao P'u Tzu treats of

two forms of elixir, the " Golden Cinnabar" or Philosopher's Stone,

and the Gold Juice. The first method involves a variety of ingredients

which may be procurable in times of peace ; but when war interrupts

communications, this method becomes impossible (iv, 17 verso, 1. 2).

The Gold Juice method is much simpler; but it is very expensive.

Ko Hung reckons that it costs 50,000 cash to make an Immortal in

this manner.

From these two practices Ko Hung sharply distinguishes the art

of Huang Po (yellow and white); i.e. the art of transmuting the

baser metals into gold and silver, without any ulterior notion of

attaining to better health, longevity, immortality or the like. The

two branches of alchemy, though apparently so rigidly divided by

Ko Hung, do not appear to belong to a different line of transmission.

For he tells us that his teacher Chang Yin practised Huang Po with Tso

Tz'u, and that they never had a single case of failure. By this method

not only lead but also iron was changed into silver.

All these practices (the exact nature of which, as in all literature

of this kind, is most inadequately revealed) were, of course, accompanied by preliminaryfasting, sacrifice,driving away of the profane, etc.

" Even a doctor," says Ko Hung in an interesting passage,3 " when

he is compounding a drug or ointment, will avoid being seen by fowls,

dogs, children, or women . . . lest his remedies should lose their

1 Biography in Hou Han Shu, chap. 112. No mention of alchemy.

2 This

expression

3

iv,

exactly

19 recto, 1. 3.

corresponds

to the Xpvao wLLuov of Zosimus.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

13

efficacy. Or again, a dyer of stuffs is in dread of evil eyes; for he

knows that they may ruin his pleasant colours."

(e) Pao P'u Tzu's attitude towardsAlchemy

Nowhere in Pao P'u Tzu's book do we find the hierophantic tone

that pervades most writings on alchemy both in the East and in the

West. He uses a certain number of secret terms, such as i

" metal-lord " and fj $ " river chariot ", both of which mean lead;

- " the

?

and f~J *?

virgin on the river ", which means mercury;

" the red boy ", which presumably means cinnabar; and

jE

finally & )} "the golden (? metal) man ", of uncertain meaning.1

But his attitude is always that of a solidly educated layman examining

claims which a narrow-mindedorthodoxy had dismissed with contempt.

He condemns those who are unwilling to take seriously either " books

that do not proceed from the school of the Duke of Chou or facts

that Confucius has not tested ". Sometimes, indeed, he is entirely

credulous, as when he accepts (iv, f. 2 recto, 1, 4) the story that Tso Tz'u

jft1?U

from the hands

received the text of the alchemic work

Tl

of a divinity jjii A. But on the preceding page he is pointing out,

quite in the manner of twentieth century sinology, that the Tao Chi

attributed by the Taoists to Yin Hsi (seventh century

Ching

g

Ji

B.C.) was in reality by Wang Tu, an obscure writer of the third

century A.D.

A belief in the possibility of manufacturing gold was, given the

circumstances of the time, perfectly sane and reasonable. In many

instances products of the West that on their arrival in China were at

first mistaken for natural substances, had recently turned out to be

manufactured. Thus glass, at first supposed to be a kind of crystal,

e

was now actually being made in Southern China:

fc

71 ,

" The 'crystal' bowls from abroad are really made by compounding

five sorts of ashes; and to-day this method is being commonly

practised in Chiao and Kuang " (i.e. parts of the modern provinces of

Kuangtung, Kuanghsi and the neighbouring portion of Annam).

used as a cosmetic,

Again, seeing the white " foreign powder ''

the Chinese were at first unaware that it wasi~made from lead. But to

ignorant people, says Pao P'u Tzu, the mere fact that gold exists in

nature, irrationally suggests that it cannot be artificially compounded.

1 Cf. the XpvadvOpw7Troof the Greek alchemists.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

14

A. WALEY-

5. Alchemy from the fifth to the tenth century.

T'ao Hung-ching (Giles, Biographical Dictionariy, No. 1896) who

was born in 451 or 452 and died in 536, was a prolific writer on Taoist

subjects, and was in later times regarded as an important alchemist.

But in his existing writings there are only fleeting allusions to alchemy.

There is, however, in one of his books (the Ting Chin Yin Chiieh,

Wieger, No. 418) an interesting reference to foreign astrology : 1fit i

" These exoteric methods [speaking

S - An iJ

- i 4

]

, .

a man's destiny by the date

of certain loose methods of determining

as

the

astronomical notions of the

the

same

of his birth] are all much

Hsiung-nu (Huns) and other foreign countries ". Alchemy in China

as elsewhere is closely bound up with astrology, and if the Chinese were

in the fifth century in contact with foreign astrology they were, it may

be assumed, in a position to be influenced by foreign alchemy.

For the centuries that follow (sixth to ninth, the period covered by

the Sui and T'ang dynasties) we have plenty of anecdotes, but an almost

complete lack of datable literature. It is, strangely enough, in Buddhist

literature (Takakusu Tripitaka, vol. xlvi, p. 791, col. 3, Nanjio, 1576)

that we find our most definite landmark. Hui-ssii (517-77) second

patriarch of the T'ien-t'ai Sect, prays that he may succeed in making

an elixir that will keep him alive till the coming of Maitreya. He will

thus escape the stigma of having lived only in a Buddha-less " betweentime ".

The wizard Ssu-ma Chang-chan, who died at an advanced age

c. 720, had a great reputation as an alchemist; but his surviving

works deal with other subjects. One of the few works on alchemy

which may with certainty be accepted as T'ang is the Shih Yao Erh Ya

(Wieger, No. 894), a dictionary of alchemical terms, by a certain

Mei Piao. Internal evidence, such as the mention of Ssu-ma Changchin, shows that the book is at least as late as the eighth

century. I should feel rather inclined from the general tone.

and style, to place it in the ninth. Several obviously foreign

terms are given. Thus for

(arsenic sulphide) an alternative

name is t ?i MjJ.1tThere . is also a reference to an alchemical

treatise called tf)]

" Treatise of the Hu (CentralAsian)

f1J

&King Yakat (Yaka0 or the like) ".2

1

Sanskrit, Hirika " The Yellow One ".

the foreign creeper ", is a poisonous

, also called i"

The

with

sound

of the Hu king's name evidently

identified

elegans.

gelseminum

plant,

recalled to the Chinese the sound of this plant-name.

Xl

2

li-ka

4or

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

15

The Problem of Lii Yen (Lii Tung-pin) and his Teacher Chung-li

Ch'uan

The second of these two is purely mythical. Lii Tung-pin (as he

is usually called) tends to materialize in the ninth century. But of the

numerous works attributed to him some are admittedly " spiritcommunications ", conveyed to the world by planchette long after

his death; others (such as the numerous tractates included in the

Taoist Canon)are obviously works of a much later date. It might have

been hoped that the Tun-huang finds would have furnished us with

datable texts; but so far as I know there are no alchemistic works

either in the Stein or in the Pelliot Collection.

It is in the tenth century that we are again on firm ground and

from then onwards we can follow the history of Chinese alchemy continuously. Our great landmark is P'?ng Hsiao's commentary on the

IJ lived during

Ts'an T'ung Ch'i (Wieger, No. 993). P'Fng Hsiao

the close of the ninth and the first half of the tenth century. In his

works 1 we again meet with the distinction (already made by Hui-ssii)

between exoteric alchemy, which uses as its ingredients the tangible

substances mercury, lead, cinnabar, and so on, and esoteric alchemy

These

kj ), which uses only the " souls " of these substances.

" souls ", called the " true " or "purified " mercury, etc., are

in the same relation to common metals as is the Taoist

Illuminate or t k to ordinary people. Presently a fresh step

is made. These transcendental metals are identified with various

parts of the human body, and alchemy comes to mean in

China not - an experimentation with chemicals, blow-pipes,

furnace, etc. (though these, of course, survived in the popular alchemy

of itinerant quacks), but a system of mental and physical re-education,

This process is complete in the Treatise on the Dragon and Tiger (Lead

and Mercury) of Su Tung-p'o, written c. 1100 2: " The Dragon is

mercury. He is the semen and the blood. He issues from the kidneys

and is stored in the liver. His sign is the trigram k'an _. The tiger

is lead. He is bread and bodily strength. He issues from the mind C,

and the lungs bear him. His sign is the trigram li _.

When the

mind is moved, then the breath and strength act with it. When the

kidneys are flushed then semen and blood flow with them."

1 Besides Wieger's No. 993, see also Wieger, No. 1020, vol. 691, a treatise by

P'6ng entitled MJ ~-jIt " Method of Esoteric Alchemy "

2

T'u Shu encyclopaedia, xviii, 300.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

16

A. WALEY-

In the thirteenth century alchemy (if it may still so be called)

no less than Confucianism is permeated by the teachings of the

Buddhist Meditation 1 Sect. The chief exponent of this Buddhicized

also known as Po Yii-chuan.

Taoism is Ko Ch'ang-kEng41,

I

'

In his treatise 4l

he

describes three methods of

2

j

g esoteric alchemy: (1) the body supplies

the element lead ; the heart,

the element mercury. Concentration supplies the necessary liquid;

the sparks of intelligence, the necessary fire. " By this means a

gestation usually demanding ten months may be brought to ripeness

in the twinkling of an eye."

The comparison of alchemy to a process of gestation is, of course,

common to East and West. The Chinese say that the processes

which produce a human child would, if reversed, produce the

Philosopher's Stone.3

(2) The second method is: The breath supplies the element lead;

the soul

supplies the element mercury. The cyclic sign + " horse "

f-,f

supplies fire; the cyclic sign - " rat " supplies water.

(3) The semen supplies the element lead. The blood supplies

mercury; the kidneys supply water; the mind supplies fire.

" To the above it may be objected," continues Ko Ch'ang-kang,

" that this is practically the same as the method of the Zen Buddhists.

To this I reply that under Heaven there are no two Ways, and that

the Wise are ever of the same heart."

There were indeed excellent reasons why Zen Buddhism should

have invaded Ko Ch'ang-kang'sdoctrines. His teacher, Ch'EnNi-wan

VA);L, was a pupil of Hsieh Fu-ming

Qfr, who under the

W

had

a

been

Zen

monk.

name Tao-kuang

f

formerly

The Hsi yu chi f

E

(Wieger,No. 1410) describes the journey

of Ch'ang-ch'un, a Taoist of this same transcendental school, to

Samarkand and even to a point near Kabul. The journey was

made in obedience to the summons of Chingiz Khan, who had at

that time conquered only part of northern China. This record is

from the hand of Ch'ang-ch'un'sdisciple, Li Chih-ch'ang,who was also

one of the party. The following conversation 4 between Chingiz

and the great alchemist, which took place in the summer of 1222,

1 Japanese, Zen. Sanskrit, Dhydna.

T'u Shu encyclopaedia, xviii, 300.

'

the 2 )Sf

See

E V, a treatise contained in the collection of Taoist

3

texts Fang Hu Wai Shih.

4 Chap. i, fol. 29.

2

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES

ON CHINESE

17

ALCHEMY

is the passage which chiefly concerns us: Chingiz: Have you any

elixir of immortality to bestow upon us ? The Master : " I have a

means of protecting life,' but no elixir of immortality."

The Khan, we are told, " was pleased with his frankness." 2

The interest of this purely mystical phase of Chinese alchemy

is that whereas in reading the works of Western alchemists one

constantly suspects that the quest with which they are concerned is a

purely spiritual one-that they are using the romantic phraseology

of alchemy merely to poeticize religious experience-in China there is

no disguise. Alchemy becomes there openly and avowedly what

it almost seems to be in the works of Bohme or Thomas Vaughan.

6. The antiquity of Alchemy in China.

It has been seen that literary references do not carry the history

of alchemy in China beyond the first century B.C. This does not, of

course, necessarily imply that it was unknown before that date. As a

result of the Burning of the Books and of Confucian hostility to rival

doctrines we possess only a small fragment of early Chinese literature.

But if we are to take the term alchemy in its narrower sense-the

attempt to compound gold out of baser substances-then it is certain

that no such attempt was at all probable in early China, where gold

was not until a comparatively late period 3 regarded as particularly

valuable either as a life-giving substance or as a medium of exchange.

Even in the first four centuries after Christ alchemy continues to

occupy a very obscure place.4 This has been explained on the ground

that the surviving histories of the period were written under influences

that were hostile to Taoism. There is, indeed, a tendency to generalize

from the example of later histories (such as the New T'ang History

which is frankly anti-Buddhist and anti-Taoist), and to regard the Han

histories, the histories of the Three Kingdoms, etc., as rigidly orthodox

Confucian works. But these works are, in reality, far from ignoring

Taoism and its magicians ; and there is no reason to suppose there was

any special prejudice against alchemy as opposed to magical practices

in general.

i.e. means of warding off evil influences.

~,

f"j t_

The doctrines of Ch'ang-ch'un and his sect will be discussed in the introduction

to a translation of the Hsi Yu Chi shortly to be published in the Broadway

Travellers Series; for the moment, therefore, I say no more about him.

3 To fix the date is difficult owing to the surprising fact that there is in Chinese

writing and vocabulary no word for gold. " Yellow metal," the usual periphrasis

can also mean bronze.

* See above, p. 5.

1

VOL.

VI.

PART I.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

18

A. WALEY-

So far, in this section, I have been considering alchemy in its

narrower sense. But it is more easily recognized in China (though

everywhere true) that the idea of manufacturing gold is closely

associated with a general attitude of early peoples towards life-giving 1

(and therefore commercially valuable) substances. In China, for

example, the attempt to make gold went on simultaneously with the

attempt to make artificially pearls, jade, and other "talismanic"

substances.2 The theory, stated far more definitely in China than

elsewhere, is that these substances are impure when found in nature

and need perfecting before their virtue can be assimilated, just as

some food needs cooking; it being believed about life-giving materials

in general that the most effectual way to utilize their power was to

absorb them in the body.

Anmongthe life-giving substances sought after by primitive people

one of the earliest to attract the attention of modern observers was the

red pigment so often found smeared on bones or deposited in graves.

The commonest form of pigment used for such purposes is in Europe

red ochre (peroxide of iron). " Among the prehistoric peoples of

Kansu," says Dr. Black,3 "the practice of depositing red pigment

with the dead" is widespread. Nor was it confined to prehistoric

times. Mr. C. W. Bishop, in his paper 4 on the bronzes of Hsin-chang

Jj 9, records the finding of red pigment both along with the human

remains in this interment and on the objects associated with these

remains. The Hsin-chEng bronzes are supposed to date from the

sixth century B.c.5 The nature of the pigment used in the Kansu

graves has not been investigated ; but the Hsin-chang tomb contained,

as Pelliot 6 expresses it, " des veritables boules de vermilion ", that is,

of cinnabar.7

This substance, however, was in China so valuable that it cannot

at any time have been used except in the burials of important people.

It is interesting also to consider the very common occurrence of the

1 I mean, of course, "life-giving " for purely mystical reasons and when used

according to the correct mystical procedure. The fact that cinnabar (for example)

is actually a poison, is irrelevant.

2

See, for example, Wieger, 1020, chap. 71, No. 27, and chap. 75, No. 1 seq.

a The Prehistoric Kansu Race, in Geological Survey of China Memoirs. Series

A, No. 5, Peking, 1925.

1 The Chinese Social and Political Science Review, vol. viii,

April, 1924.

5 See Wang Kuo-wei, Shinagaku, vol. iii, No. 9 (1924), p. 723.

6

T'oung Pao, 1924. p. 255.

7 An article in

Shina-gaku, iii, No. 7 (1923), p. 563, uses the term Jf rfj, which

is equally decisive.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

19

word in Chinese place-names (Tan-yang

, in Fukhien, Hupeh,

in Kiangsu).

Corea, etc.; Tan-lng i f,&in Ssechuan; Tan-t'u-R

Are these the sites of ancient cinnabar mines, some of them already

worked-out in historic times ? Or does the word merely mean red ?

These are questions which are worth investigation. In any case,

it is certain that cinnabar was one of the most important "life-giving "

substances sought for by the ancient Chinese, and I would suggest

that the formule of early Chinese alchemy are essentially receipts

for compounding cinnabar. The idea that the object of making

cinnabar was to use it as a charm for turning base metals into gold

seems to me to be an afterthought, and one which was never properly

assimilated. The chief object of alchemy remains always (till the

art becomes purely abstract and esoteric) the production of the

" spirit-cinnabar," "magic cinnabar." An " alchemy "

0i )

concerned merely with the fabrication of cinnabar no doubt goes back

to very early times. When, towards the middle of the Chou dynasty,

gold (under the influence of China's nomad neighbours to the north

and north-west) began to take its place as the most valued medium

of exchange, cinnabar could not remain the alchemist's final objective,

and appended to his formulae we find the statement: " When the

cinnabar has been made, the gold will follow without further difficulty."

Thus alchemy in China is essentially a revival of stone-age notions

(the life-giving power of red pigment, etc.) that had sunk to folk-lore

level. The craftsman's magic 1 that surrounded the working of gold

doubtless went back to a time when gold was, like cinnabar among

the Chinese, a life-giving substance valuable for its own magic

properties. It was natural that the Chinese should add gold to their

hierarchy of life-giving substances, appending it to their alchemical

processes as a sort of " super-cinnabar ".

If now we go back again to the passage quoted at the beginning

of this essay, we may analyze the various stages enumerated by the

wizard Li Shao-chiin as follows: (1) Sacrifice to the stove. (2)

Summon spirits. These are precautions common to all metallurgic

operations among primitive peoples. (3) Cinnabar changed into

gold. Gold has already usurped the place of cinnabar as the most

magical of substances. (4) Make vessels out of this gold and drink

1 Among early peoples no technical operation is carried on without such magic,

which is considered essential to success. The Chinese in learning how to work gold

could not have failed at the same time to learn the magic observances with which

among their teachers the working of gold was associated.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

20

A. WALEY-

out of them. This describes how the magic power of the gold is to be

absorbed into the system. (5) You will then increase your span of

life and see hsien {h in the island of P'Eng-lai. The hsien of P'eng-lai

are always associated with herbal magic, and we are here branching

off on to a totally different system of wizardry, familiar to us through

early Chinese literature. This herbal magic seems, indeed, to have

been the craft of the educated and ruling classes as opposed to the

mineral magic that only gradually drifted up out of the realm of

folk-lore. (6) You may then perform the sacrifices fing and shan.

Here we have branched off on to yet another line of magic-the

mystic ritual of kingship, which is here superimposed on all the rest.

7. Connectionwith Alchemy Elsewhere

It has already been suggested that the introduction of gold into

China involved not merely the importation of the substance itself

or the knowledge how to work it, but also of the magical ideas connected

with the craft. These ideas were super-imposed on the magical ideas

connected with *the native precious substances, such as jade and

cinnabar. But how far did definitely alchemistic notions from abroad

-that is, notions assuming the possibility of changing base metals

into gold-affect the history of alchemy in China ?

As is well known, the history of alchemy outside China begins

with texts written in Greek at Alexandria, none of which seem to be

older than the second century A.D. Some of these texts (though not,

I think, the earlier of them) indicate that the art was introduced into

Egypt by learned Persians, such as Ostanes, whom one may identify,

if one will, with the historical person of that name. To the ancients

of the classical world Chaldea was the home of astrology and magic;

this is a judgment which our vastly greater knowledge of Babylonian

literature enables us to confirm, and there is an antecedent probability

that alchemy, a form of magic intimately connected with astrology,

also had its origin in Babylon, or " Persia " as the ancients freely

called the whole cultural realm from Mesopotamia to Turkestan.

But until 1925 nothing had come to light in this region which could

be interpreted as throwing any light on the origins of alchemy. In

that year appeared Campbell Thompson's On the Chemistry of the

Ancient Assyrians,1 and this was immediately followed by an article

1 The same texts were published almost simultaneously by Zimmern. Dr. Eisler's

article in the ChemikerZeitung was followed by others in the Zeitschriftfiar Assyriologie

and elsewhere. The details of the ensuing controversy do not here concern us.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE ALCHEMY

21

Der Babylonische Ursprung der Alchimie, published in the Chemiker

Zeitung (Nos. 83 and 86) by Dr. R. Eisler. The texts in question

are said to date from the seventh century B.C. They are metal

worker's formulae,and as such they naturally involve the usual magic

procedures. But they are not concerned with the making of gold,

and will turn out, I think, when our knowledge of the subject is

increased, to be typical of the formulaethat were inseparable from all

primitive technicology. Whether they have at one point a special

connection with what later turned into alchemy depends on the

interpretation of the term an-kubu " divine embryo," -and of the

sentence in which it occurs. Campbell Thompson 1 translates, " Thou

shalt bring in embryos . . . thou shalt make a sacrifice before the

embryos ", and Thureau-Dangin2 explains that the kubu (embryo)

is " une sorte de demon ". But according to Dr. Eisler 3 it is the

minerals placed in the furnace that are technically referred to as

of the Greek

" embryos ", and he invokes the term dvOpwrrcndpov

alchemists, applied by them to the " issue " which proceeds from

the mystic fusion of alchemic ingredients. This view has not, so far

as I know, been supported by any Assyriologist. But the occurrence

of the term " embryo " in connection with a magico-technical process

at once recalls the widely-spread use of foetuses, embryos, childcorpses, and the like.4 I cannot help thinking that the an-kubus

were something more particular than " une sorte de demon ". It is

likely enough that they were either dried fcetuses such as were used by

Indian magicians, or carven objects used to represent these. That

alchemy was to some extent an atavistic revival of the circle of ideas

to which the Campbell Thompson texts belong is undeniable. But

I do not think that they can be regarded as belonging to the history

of alchemy itself.

GREEK ALCHEMY

I have already referred to the rise of alchemy in Alexandria somewhere about the second century A.D. There is some reason for

supposing that it had not been established in Egypt for any

considerable time before the appearance of the earliest texts. Ancient

Egyptian literature knows nothing of it, and it is wholly lacking in

1 Op. cit., p. 57,

2Revue d'Assyriologie, 1922 (xix), p. 81.

S Revue de Synthase Historique, xli (1926), and elsewhere.

4 Particularly common in India. See Meyer's translation of the

Arthah.istra,

p. 378, p. 649, etc.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

22

A. WALEY-

the huge collection of magical texts published by Lexa in 1925.1

Many of the so-called alchemistic texts are mere craftsman's formulve,

accompanied by the usual element of magic. The making of gold

out of common metals or the giving of a golden appearance to such

metals is only one of the topics discussed. The aim of Greek alchemy

remains wholly objective. It is the metals, not the practitioner, whose

constitution is to be ameliorated. The 8OEovv"8wp,so far from conferring immortality or even better health, " slays all living things,"

a 4civ-ra VEKPO&. Where, outside China, do we first meet with

the idea of eating the product of alchemic fusion, of using it not merely

as a healer of metals but also as a medicine for man ? So far as I

know this theory makes its first appearance in the Rasaratnakara

of Ndgarjuna-the pseudo-Ndgdrjuna, as one might say; for the

author of the work used the name of the great Buddhist patriarch

and reputed wonder-worker, just as Western alchemists used the

names of Moses, Aristotle, Roger Bacon, and Thomas Aquinas.

Alberuni, writing in 1031, places the alchemist " Nigarjuna " about a

hundred years before his own time. It has hitherto been assumed that

alchemistic ideas can at an early period only have reached India from

the West. Thus in his recent History of Sanskrit Literature (p. 460),

Dr. Berriedale Keith argues that the Arthaidstra must be as late as

the period of Greek influence because of its references to alchemy.

It is hard, however, to see what connection there is between the very

ill-defined suvarna-pdka (gold-making) of the Arthaidstra and the

complicated network of theories that constitute Greek alchemy. The

mere idea that gold might be manufactured was surely not confined

to the Greeks. We have already seen that it existed in China in the

first century B.C. I do not mean to imply that a Chinese influence

on India existed at this early period. When, however, we find

Nagarjuna at a period corresponding to the Sung dynasty regarding

quicksilver as an important element in alchemy and believing in the

power of the "philosopher's stone " to protect and prolong life, we

may reasonably ask whether at this period a direct influence 2 from

China may not be possible.

In 648 the Chinese envoy Wang Hsiian-ts'?, who between 643

and 665 fulfilled four missions to India, brought back with him to

China a Brahmin named Ndrayanasvamin, who won the confidence

of the Emperor T'ai Tsung. The Brahmin was a specialist in

x La Magie ddns l'Egypte Antique, 2 vols. text, 1 vol. plates. Goes down to

the Coptic period.

2 Dating, no doubt, from the

preceding T'ang dynasty.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

NOTES ON CHINESE AItCHEMY

23

" Prolonging Life ". We do not know what his means were, whether

herbal or mineral. Some time before 657 he returned to India. But

in 657 we find his patron Wang Hsiian-ts'E petitioning the new

Emperor (T'ai Tsung died in 649) not to let Narayanasvamin go back

to India till his elixir had been given a fair trial. Evidently, then,

the magician had visited China for a second time. According to the

New T'ang History and the Yu Yang Tsa Tsu, Ndrayanasvamin

died in Ch'ang-an. But a much earlier authority (the Fang Shih Lun

of Li T-yuii 1) says that the Emperor Kao Tsung sent him back to

India, and this is supported by the Old T'ang History.

In 664-5 the Buddhist monk Hsiian-chao 2 was ordered by Kao

Tsung to fetch from Kashmir another Indian magician, named

Lokdditya (Lu-chia-i-to), who was supposed to possess the drug 0

This Hindu was at the Chinese Court in 668; we

of Longevity.

do not know whether he stayed in China or returned to India.

Nardyanasvamin, if not Lokdditya, certainly returned at least

once to India, and it is certain that while at Ch'ang-an he must have

picked up from his Chinese confreres some notions of Chinese alchemy.

But the influence was not all in one direction; for we have seen 3

a Chinese writer, probably of two centuries later, giving a Sanskrit

name to the chemical, arsenic sulphide. That reactions of this kinda definite give and take, went on between China and India during

the T'ang dynasty is, I think, beyond doubt. A much more difficult

question is the extent to which Chinese alchemy was influenced by

that of other countries in the early centuries of the era; and this

question is obviously complicated by the fact that we are far from

certain whether in Central Asia, the most likely source of influence,

alchemy at this time existed at all. We know that An Shih-kao,

the famous Parthian translator of Buddhist scriptures, who worked

in China in the second century, was also skilled in the magic and

astrology of his own country. But whether he may have acted as

a "' carrier " of Iranian alchemy to China we do not know, for the

simple reason that we are still uncertain whether such a thing as

Iranian alchemy ever existed. The Central Asian king Yakat (Yakar

or the like) to whose treatise I have already referred 3 remains an

enigma. It is probable, but not quite certain, that he proves the

1 Quoted in the T'u Shu encycloppedia, xviii, 289, i, 16.

2 See

Chavannes, Voyages des Pdlerins Bouddhistes, p. 21, and the new Tripitaka

(Takakusu's edition), vol. li, p. 2, col. 1 (No. 2066).

3 p. 14.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

24

NOTES

ON CHINESE

ALCHEMY

existence of a pre-Muhammedanalchemy in Central Asia. As to his

nationality the name does not, to my knowledge, give us any clue.

He may have been Eastern Iranian (Sogdian) or Turk. But after

the Arabic Conquest the influence was, I believe, all from East to West.

Further examination of Arabi@alchemy will show, I am convinced,

that it contains a vast element which it owes to China rather than to

the Greek world. In particular the idea of the " philosopher's stone "

as an elixir of life is a contribution of the Chinese. The second period

of their influence was the time of the Mongol conquest. We have

seen how the Chinese alchemist Ch'ang-ch'un visited Samarkand in

1221-2. Here he came in contact with the leaders of the

Muhammedan community, and we cannot doubt that the teachings

of a holy man, summoned from so great a distance by the Khan

himself, made a considerable impression on the mysticism of Eastern

Persia, just as the artists summoned to Persia by the Mongol Khans

had a lasting influence on the pictorial art of the country. How

soon this influence is reflected in Arabic literature I do not know.

But it is manifest (travelling, no doubt, via the Arabs) in much of the

mystic literature of our own Renaissance, in which the quest of the

alchemist seems to have become purely subjective and internal.

This content downloaded from 203.15.226.132 on Sat, 10 Jan 2015 10:08:14 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Myth, Cosmology, and The Origins of Chinese Science - Major PDFDocument20 pagesMyth, Cosmology, and The Origins of Chinese Science - Major PDFernobeNo ratings yet

- Daoist Studies Bibliography GuideDocument32 pagesDaoist Studies Bibliography GuideChatounerNo ratings yet

- The Book of Changes - I Ching - Arthur WaleyDocument22 pagesThe Book of Changes - I Ching - Arthur Waleyvaraprasad119No ratings yet

- Jiabs 12-1Document171 pagesJiabs 12-1JIABSonline100% (1)

- The Dunhuang Chinese SkyDocument48 pagesThe Dunhuang Chinese SkynorzangNo ratings yet

- The Needham QuestionDocument6 pagesThe Needham QuestionRoberto Velasco MabulacNo ratings yet

- Zurcher - The Buddhist Conquest of China - 3rd Ed - 2007Document511 pagesZurcher - The Buddhist Conquest of China - 3rd Ed - 2007Mehmet TezcanNo ratings yet

- Ancient Chinese Alchemy TreatiseDocument85 pagesAncient Chinese Alchemy Treatiseal-gazNo ratings yet

- Health and Philosophy in Pre-And Early Imperial China: Michael Stanley - BakerDocument36 pagesHealth and Philosophy in Pre-And Early Imperial China: Michael Stanley - BakerDo Centro ao MovimentoNo ratings yet

- Jejum Seeking - Immortality - in - Ge - Hongs - Baopuzi PDFDocument30 pagesJejum Seeking - Immortality - in - Ge - Hongs - Baopuzi PDFGabriela-foco OrdoñezNo ratings yet

- Creel, Herrlee Glessner - Studies in Early Chinese Culture, First Series (1938)Document300 pagesCreel, Herrlee Glessner - Studies in Early Chinese Culture, First Series (1938)Victor BashkeevNo ratings yet

- Vegetal Philosophy and the Roots of ThoughtDocument15 pagesVegetal Philosophy and the Roots of Thoughtgiorgister5813No ratings yet

- Mythical MountainsDocument15 pagesMythical MountainsΒικτορ ΦοινιξNo ratings yet

- Journal of The American Oriental Society Vol 40Document898 pagesJournal of The American Oriental Society Vol 40Helen2015No ratings yet

- The Iconography of The Dioscuri On A SarDocument10 pagesThe Iconography of The Dioscuri On A SargpintergNo ratings yet

- Tibetan Scholars Discuss Central Asian BuddhismDocument256 pagesTibetan Scholars Discuss Central Asian Buddhismdvdpritzker100% (2)

- Ralph Waldo Emerson: Nature (1836)Document2 pagesRalph Waldo Emerson: Nature (1836)Agatha RodiNo ratings yet

- Aristotle's Monograph On The PythagoreansDocument14 pagesAristotle's Monograph On The PythagoreansNadezhda Sergiyenko100% (1)

- Varuna and DhrtarāstraDocument21 pagesVaruna and Dhrtarāstracha072No ratings yet

- Doré - 09 Chinese Superstitions Taoist PersonagesDocument404 pagesDoré - 09 Chinese Superstitions Taoist PersonagesBertran2No ratings yet

- Huang Yuan Hua's Heart Method of the Four SagesDocument11 pagesHuang Yuan Hua's Heart Method of the Four Sagesdc6463100% (1)

- The Hundred Words Stele by Lu Dongbin 4 Commentary by Zhang SanfengDocument2 pagesThe Hundred Words Stele by Lu Dongbin 4 Commentary by Zhang SanfengaaNo ratings yet

- Ananda K. Coomaraswamy - The-Dance-of-SivaDocument13 pagesAnanda K. Coomaraswamy - The-Dance-of-SivaRoger MayenNo ratings yet

- The Tradition of Stephanus Byzantius PDFDocument17 pagesThe Tradition of Stephanus Byzantius PDFdumezil3729No ratings yet

- Needham Joseph Science and Civilisation in China Vol 5-1 Chemistry and Chemical Technology Paper and PrintingDocument256 pagesNeedham Joseph Science and Civilisation in China Vol 5-1 Chemistry and Chemical Technology Paper and PrintingAhmed MukhtarNo ratings yet

- Work of Geber - Text PDFDocument160 pagesWork of Geber - Text PDFernobeNo ratings yet

- Philosophy of Mind in China PDFDocument9 pagesPhilosophy of Mind in China PDFKarla PugaNo ratings yet

- Translation of The Dunhuang Star ChartDocument4 pagesTranslation of The Dunhuang Star ChartmkljhrguytNo ratings yet

- The Man Bird Mountain Writing Prophecy ADocument54 pagesThe Man Bird Mountain Writing Prophecy AmikouNo ratings yet

- Gray, David. Experiencing The Single SavorDocument10 pagesGray, David. Experiencing The Single SavorvkasNo ratings yet

- PDFDocument4 pagesPDFJudas FK TadeoNo ratings yet

- AK Coomaraswamy, Origin of The Buddha ImageDocument44 pagesAK Coomaraswamy, Origin of The Buddha Imagenandana11100% (2)

- Hieroglyphic Texts F R o M Egyptian Stelae-, Part 12, Edited B y M.L. Bierbrier, British Museum PressDocument3 pagesHieroglyphic Texts F R o M Egyptian Stelae-, Part 12, Edited B y M.L. Bierbrier, British Museum PressKıvanç TatlıtuğNo ratings yet

- Qimeng 3Document82 pagesQimeng 3Alex Muñoz100% (1)

- Coomaraswamy A Yakshi Bust From BharhutDocument4 pagesCoomaraswamy A Yakshi Bust From BharhutRoberto E. GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Jung, William Blake and Our Answer To JobDocument24 pagesJung, William Blake and Our Answer To JobChivi SpearNo ratings yet

- Burton Watson - The - Tso - ChuanDocument73 pagesBurton Watson - The - Tso - ChuanMiguel Vázquez AngelesNo ratings yet

- Time in Chinese AlchemyDocument17 pagesTime in Chinese AlchemyJohn Dee50% (2)

- 2019 Daoing Medicine Practice Theory ForDocument49 pages2019 Daoing Medicine Practice Theory ForChristian PerlaNo ratings yet

- Impressive Sculpture of Shiva Battling the Elephant 35Document20 pagesImpressive Sculpture of Shiva Battling the Elephant 35Rahul GabdaNo ratings yet

- The Black Magic in China Known As Ku PDFDocument31 pagesThe Black Magic in China Known As Ku PDFRicardo BaltazarNo ratings yet

- The Upper Paleolithic Burial Area at Predmostı: Ritual and TaphonomyDocument19 pagesThe Upper Paleolithic Burial Area at Predmostı: Ritual and TaphonomyMajaNo ratings yet

- Moral Values in Ancient Egypt PDFDocument119 pagesMoral Values in Ancient Egypt PDFgabrielNo ratings yet

- Adeptas Femininas TaoismosDocument15 pagesAdeptas Femininas TaoismosÉdison Nogueira da FontouraNo ratings yet

- Daoist Temple Painting PDFDocument362 pagesDaoist Temple Painting PDFHappy_DoraNo ratings yet

- Daoist ArtDocument11 pagesDaoist Artczheng3100% (1)

- Scripture of Wisdom and Life: Hui-Ming ChingDocument19 pagesScripture of Wisdom and Life: Hui-Ming ChingfrancoissurrenantNo ratings yet

- Ascent of Sap: 3 Theories: (A) Godlewski S Relay-Pump TheoryDocument11 pagesAscent of Sap: 3 Theories: (A) Godlewski S Relay-Pump TheoryRahulBansumanNo ratings yet

- Philebus Commentary With Appendices and BibiliographyDocument7 pagesPhilebus Commentary With Appendices and BibiliographybrysonruNo ratings yet

- A Bilingual Graeco-Aramaic Edict of ASoka - Carratelli and CarbiniDocument40 pagesA Bilingual Graeco-Aramaic Edict of ASoka - Carratelli and CarbinipantognosisNo ratings yet

- 9 Taoist Books On The ElixirDocument25 pages9 Taoist Books On The ElixirRenata BerkiNo ratings yet

- Cronologia Storica TaoismoDocument5 pagesCronologia Storica TaoismoHerta ManentiNo ratings yet

- Hunyuan XinfaDocument1 pageHunyuan XinfaCarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Scroll of Shongto - The COS 9 Page Fun Print and Tape and Roll Up Taoist ScrollDocument9 pagesScroll of Shongto - The COS 9 Page Fun Print and Tape and Roll Up Taoist ScrollshangtsungmakNo ratings yet

- Han Shan - The Cold Mountain Poems (Trad. Gary Snyder)Document10 pagesHan Shan - The Cold Mountain Poems (Trad. Gary Snyder)Pablo Plp100% (1)

- Walwyn William-The Compassionate Samaritane-Wing-W681B-168 E 1202 1 - P1to46Document46 pagesWalwyn William-The Compassionate Samaritane-Wing-W681B-168 E 1202 1 - P1to46DannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 2015 DENDLE Review Minois Atheists BibleDocument3 pages2015 DENDLE Review Minois Atheists BibleDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1790 A Narrative of The Disinterment of Milton's Coffin ...Document32 pages1790 A Narrative of The Disinterment of Milton's Coffin ...DannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1921 CRAIG Dryden's LucianDocument24 pages1921 CRAIG Dryden's LucianDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1941 HUNG The Inner Chapters of Pao-'P'U-tzu (Tr. Davis & Kuo-Fu)Document30 pages1941 HUNG The Inner Chapters of Pao-'P'U-tzu (Tr. Davis & Kuo-Fu)DannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- Tardieu Michel ManichaeismDocument131 pagesTardieu Michel ManichaeismGuillermo R. Monroy100% (7)

- Myself am Hell: Exploring Milton's Depiction of Hell in 'Paradise LostDocument16 pagesMyself am Hell: Exploring Milton's Depiction of Hell in 'Paradise LostDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1940 WILLIAMS 'Introduction' (The English Poems of John Milton)Document9 pages1940 WILLIAMS 'Introduction' (The English Poems of John Milton)DannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- Literary History vs Criticism - What is the Proper Focus of English StudiesDocument11 pagesLiterary History vs Criticism - What is the Proper Focus of English StudiesDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1940 WILLIAMS 'Introduction' (The English Poems of John Milton)Document9 pages1940 WILLIAMS 'Introduction' (The English Poems of John Milton)DannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1949 STAPLETON, LEWIS, TAYLOR The Sayings of Hermes Quoted in Teh Ma' Al-Waraqi of Ibn UmailDocument22 pages1949 STAPLETON, LEWIS, TAYLOR The Sayings of Hermes Quoted in Teh Ma' Al-Waraqi of Ibn UmailDannieCaesar100% (2)

- 1926 HOLMYARD (Ed) A Romance of ChemistryDocument18 pages1926 HOLMYARD (Ed) A Romance of ChemistryDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1730 ILIVE The Layman's Vindication of The Christian ReligionDocument250 pages1730 ILIVE The Layman's Vindication of The Christian ReligionDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

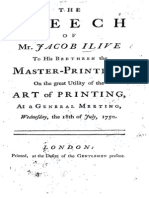

- 1750 ILIVE The Speech ... To His Brethren The Master-PrintersDocument6 pages1750 ILIVE The Speech ... To His Brethren The Master-PrintersDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1935 HUNG ... The Fourth & Sixteenth Chapters of Pao-P'U-tzu (Tr. Wu & Davis)Document65 pages1935 HUNG ... The Fourth & Sixteenth Chapters of Pao-P'U-tzu (Tr. Wu & Davis)DannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- Cardan Book of My Life 1930Document362 pagesCardan Book of My Life 1930DannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- Guide to the Beyond: Analysis of the Composition of the Book of Two WaysDocument15 pagesGuide to the Beyond: Analysis of the Composition of the Book of Two WaysDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1738 ILIVE The Oration Spoke at Trinity-Hall in Aldersgate-StreetDocument40 pages1738 ILIVE The Oration Spoke at Trinity-Hall in Aldersgate-StreetDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1931 WALKER John Ellistone & John SparrowDocument1 page1931 WALKER John Ellistone & John SparrowDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1730 ILIVE The Layman's Vindication of The Christian ReligionDocument242 pages1730 ILIVE The Layman's Vindication of The Christian ReligionDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1754 (ILIVE) Some Remarks ...Document39 pages1754 (ILIVE) Some Remarks ...DannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1733 ILIVE The Oration Spoke at Joyners-Hall in ThamesstreetDocument76 pages1733 ILIVE The Oration Spoke at Joyners-Hall in ThamesstreetDannieCaesarNo ratings yet

- 1912 GOLLANCZ (TR.) The Book of ProtectionDocument241 pages1912 GOLLANCZ (TR.) The Book of ProtectionDannieCaesar100% (2)

- La Kabylie Et Les Coutumes Kabyles 1/3, Par Hanoteau Et Letourneux, 1893Document607 pagesLa Kabylie Et Les Coutumes Kabyles 1/3, Par Hanoteau Et Letourneux, 1893Tamkaṛḍit - la Bibliothèque amazighe (berbère) internationale100% (3)