Professional Documents

Culture Documents

WHO-Primary Health Care

Uploaded by

ferry7765Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

WHO-Primary Health Care

Uploaded by

ferry7765Copyright:

Available Formats

SIXTY-SECOND WORLD HEALTH ASSEMBLY

Provisional agenda item 12.4

A62/8

9 April 2009

Primary health care, including

health system strengthening

Report by the Secretariat

1.

There have been many calls for a renewal of primary health care at several international,

regional, and national conferences organized by, or in collaboration with, WHO,1 and at 2008 regional

committee meetings, coinciding with the 30th anniversary of the Declaration of Alma-Ata, which

articulated the values of Health for All through primary health care, addressing both priority health

needs and the fundamental determinants of health, so as to enable people to lead socially and

economically productive lives, and thus drive overall development.

2.

Member States, in their calls for a renewal of primary health care, have reaffirmed their

commitment to the values of equity, solidarity and social justice, and the principles of multisectoral

action and community participation. The calls represent the ambition to deal effectively with current

and future challenges to health, mobilizing health professionals and lay people, government

institutions and civil society around an agenda of transformation of health-system inequalities, service

delivery organization, public policies, and development.

3.

The health of the worlds population has improved over the last 30 years and can be partly

attributed to better nutrition, water supply, sanitation, housing, and education. Although some

countries have shown sustained improvement in health outcomes, others have lagged behind or even

experienced reversals. In part these differences can be attributed to socioeconomic, political and

ecological constraints. However, low-income countries have found it difficult to cope with rising

commodity prices, recession, structural adjustment programmes, political instability, civil strife, the

emergence of HIV/AIDS, and others. But differences in health outcomes are also related to investment

in health and financing, decentralization, human resource and other major health-sector policies.

4.

There are important lessons in the successes and failures of the last 30 years: health systems do

not automatically yield the optimal and most effective balance of promotion, prevention, cure and

palliation; and they do not naturally move towards the production of enhanced and more equitable

health outcomes, greater solidarity and social justice. Leadership and a sense of direction require

sustained commitment and an approach embedded in, and a driver of, overall development.

5.

Health authorities in many countries are aware that progress towards improved health outcomes,

including, but not limited to, the Millennium Development Goals, is too slow and unequal, that

Ottawa 1986, Ljubljana 1996, Jakarta 1997, Mexico 2004, Bangkok 2005, Buenos Aires 2007, Beijing 2007,

Bangkok 2008, Jakarta 2008, Tallinn 2008, Ouagadougou 2008, Doha 2008.

A62/8

performance does not meet expectations, and that they are ill-prepared to respond to challenges and

demands. Many recognize the potential of primary health care for providing a stronger sense of

direction and unity in segmented and fragmented health systems, and for providing the framework that

integrates health into all policies.

6.

This dissatisfaction is echoed by international agencies, global health initiatives, donors, and

civil society organizations. Consequently, global stakeholders are increasingly recognizing the need

for improved health-systems performance based on the values of primary health care.

7.

Further support has come from two reports published in 2008. The report of the Commission on

Social Determinants of Health1 documented widening gaps in health outcomes, both within and

between countries, and challenged governments to make equity an explicit policy objective in all

government sectors. The Commissions analysis of underlying social, economic, and political causes

of ill-health, and of the methods most likely to provide solutions, makes a convincing case for, and

endorses, a renewed focus on primary health care.

8.

In addition, The world health report 20082 noted that, in rich and in poor countries alike, a

health sector organized according to the tenets of primary health care had the greatest potential for

producing better health outcomes, improving health equity and responding to social expectations. The

report identifies the key areas where policy change is required in order to ensure that health systems

are based on the values and principles of primary health care.

THE HEALTH CHALLENGES

9.

There are differences not only in health outcomes between countries, but also national

inequalities in access, coverage and expenditure.

10. Rising social expectations regarding health and health care, fuelled by modernization, greater

access to information and improved health literacy, are driving demand for more people-centred

access, better community health protection and more effective participation in decisions that affect

health. There is pressure on policy makers and political leaders to steer their health systems towards

health equity, social justice and solidarity.

11. There are unprecedented opportunities to do so. In recent years, countries have gained

experience and knowledge; there is the mutually reinforcing demand for change from populations,

policy makers and the global health community; and, as indicated by the Report of the Secretariat

regarding monitoring of the achievement of the health-related Millennium Development Goals,3 there

is a growing consensus that health will not improve without functioning health systems, that health

systems function best when they are based on primary health care, and that there is an opportunity to

align more fully the agenda for responding to specific diseases with the agenda for strengthening

1

Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the gap in a generation: Health equity through action on

the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Geneva, World Health

Organization, 2008.

2

World Health Organization. The world health report 2008: Primary health care, now more than ever. Geneva,

World Health Organization, 2008.

3

Document EB124/10.

A62/8

health systems. The rapid expansion and growing economic and social weight of the health sector a

long-term trend across the world, with the exception of fragile States provides leverage to obtain the

policy changes that primary health care requires.

AN AGENDA FOR ACTION

12. There are four broad policy areas for essential changes: dealing with health inequalities by

moving towards universal coverage; putting people at the centre of service delivery; integrating health

into public policies across sectors; and providing inclusive leadership for health governance.

13. The changes rely on the alignment of the different components or building blocks of health

systems, i.e. the health workforce; the health information system; the systems to provide access to

medical products, vaccines, and technologies; the financing system; and leadership and governance,

and on the way they jointly translate health-sector inputs into overall outcomes.1

14. The policies must be shaped by the Member States themselves, and tailored to the specificities

of each country. The global health community must also use its power of mobilization and influence to

facilitate the renewal.

15. Dealing with health inequalities by moving towards universal coverage. This means moving

towards a sufficient supply of service networks (inclusive of the human resources, infrastructure,

resources, management and steering required), where financial and other barriers to access are

removed, and where families are protected against the financial consequences and impoverishment

that may result from seeking care. Moving towards universal coverage constitutes the core strategy to

ensure that health systems contribute to health equity, social justice, and the elimination of exclusion.

It does not, however, eliminate the need for tackling the social determinants of health inequalities,

through a whole-of-society approach as recommended by the Commission on Social Determinants,

nor does it preclude the need for efforts at reaching the unreached or for systematic monitoring and

documentation of health inequalities and exclusion.

16. Depending on the national context, a step-by-step progression towards universal coverage

requires a combination of (i) the extension of health-care networks where they are not available;

(ii) the shift from reliance on user fees levied on the sick to the solidarity and protection provided by

pooling and prepayment; and (iii) the development of mechanisms of social health protection. In highas well as in low-income countries, present levels and trends of domestic expenditure on health could

allow for a greater degree of universality.

17. In many countries, purchase of an essential set of health interventions for all is beyond national

capacity. Increased external financial assistance for health will be required for some years to come,

including through innovative mechanisms. Scepticism about aid effectiveness has been replaced by

recognition of the need for donors to direct financial flows towards country-led priorities and

initiatives in ways that strengthen existing infrastructures, reduce fragmentation and duplication, and

minimize transaction costs. Channelling aid in ways that build up the institutional capacity to manage

the financing of the system can accelerate the extension of service networks together with the

development of social health protection. This would improve synergies between external and domestic

1

World Health Organization. Everybodys business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes.

WHOs framework for action. Geneva, World Health Organization, 2007.

A62/8

funding: the visibility and strategic importance of external funding should not obscure the fact that

more than 75% of health expenditure in the average low-income country comes from domestic

sources.

18. The move towards universal coverage also remains an unfinished agenda in high-income

countries, where cost containment is having a serious effect on equity of treatment.

19. Putting people at the centre of service delivery. Health services must pay far more attention

to putting the patient first, and to continuity and integration of care. The organization of a

comprehensive continuum of care along the life-cycle is particularly important, encompassing the full

range of health actions, from prevention and promotion to curative and palliative care. The public,

private-for-profit, or private-not-for-profit nature of health care delivery is far less critical than the

degree to which services, in each context, can be organized so as to present these actions.

20. To ensure that services deliver appropriate care, they have to be designed and organized around

close-to-client networks of primary care teams, with the responsibility for the health of a defined

population, and with the capacities to coordinate the inputs of hospitals, specialists, and other services

(including supplies and logistics) that can contribute to the health of that population. In many

countries, health districts are an appropriate planning unit for organizing service delivery in line with

these principles.

21. The health-care delivery landscape has become far more complex over the last decades. Along

with governmental services, the offer of care now generally includes a range of providers,

governmental and nongovernmental, for-profit and not-for-profit, and a range of services, including

traditional medicine. This variety can add value to service delivery, provided its responsiveness to the

variety of problems and expectations and its entrepreneurial dynamism is harnessed to contribute to

improved health and health equity, and mechanisms are in place to ensure safety and consumer

protection.

22. There are currently new opportunities for countries to take advantage of recent reviews of

experience with different, context-sensitive approaches to the integration of traditional and

conventional medicine, building on that accumulated knowledge to contribute to the necessary

reorientation of health care delivery towards people-centred primary care.

23. Putting people at the centre of service delivery is not merely a question of designing the

appropriate service delivery models. The improvement of basic health infrastructures, services and the

workforce requires long-term commitment and investment. Given the critical shortage of health

workers and the immediate impact on health, investment in the health workforce, including through

professional associations and training institutions, is decisive, in high- as well as in low-income

countries.

24. Multisectoral action and health in all policies. The deliberations of the regional committees,

the Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health and The world health report 2008

have reiterated the need to step up efforts to improve health by acting on wider social, economic, and

environmental causes of ill health and health inequalities.

25. Better public policies, within and beyond the health sector, represent a huge untapped potential

to improve health. Public health interventions, from public hygiene and disease prevention to health

promotion and the establishment of a rapid response capacity are of critical importance for health

outcomes and for securing and sustaining public trust in the health system.

A62/8

26. Public authorities, across all government sectors, must also assume their responsibilities for

ensuring that health considerations are given their rightful place in the deliberations on other policy

domains, such as gender equality, consumer protection or labour policies. Health authorities must

create the conditions under which other sectors can incorporate health considerations within their

policies and outcomes. Health impact assessments offer promising avenues for more concrete

multisectoral policy dialogue.

27. Inclusive leadership and effective government for health. In many countries there is a need

for substantial reinvestment in country capacity to govern the health sector. The enhanced

responsibilities must be accompanied by new forms of leadership for health, particularly in a context

where political and administrative decentralization offers both challenges and opportunities.

28. While each Member State has its own way of governing its health system, health ministries have

the ultimate responsibility for health-system development. However, given the complexity of the

health sector, the responsibility has to be exercised through collaborative models of policy dialogue

with multiple stakeholders, from professional organizations to United Nations agencies, from

development banks to civil society, from womens and youth groups to networks of patients.

29. These new ways of operating will require reinvestment commensurate with the growth and

weight of the health sector in society, in leadership capacities, in the gathering and use of information,

and in knowledge and research. There is a clear need for building more effective, more proactive and

more collaborative ways of governing the health sector.

30. An earlier version of this report was considered by the Executive Board at its 124th session in

January 2009.

ACTION BY THE HEALTH ASSEMBLY

31. The Health Assembly is invited to consider the draft resolutions contained in resolutions EB124.R8

and EB124.R9.

You might also like

- The politics of health promotion: Case studies from Denmark and EnglandFrom EverandThe politics of health promotion: Case studies from Denmark and EnglandNo ratings yet

- Public Health Future EngDocument19 pagesPublic Health Future EngKiros Tilahun BentiNo ratings yet

- New Health Systems: Integrated Care and Health Inequalities ReductionFrom EverandNew Health Systems: Integrated Care and Health Inequalities ReductionNo ratings yet

- The Mixed Health Systems Syndrome: Sania NishtarDocument2 pagesThe Mixed Health Systems Syndrome: Sania Nishtarapi-112905159No ratings yet

- Health Care SystemsDocument10 pagesHealth Care SystemsThembaNo ratings yet

- Primary Health Care WHO OverviewDocument16 pagesPrimary Health Care WHO OverviewlilaningNo ratings yet

- Sanitation Problem Health SectorDocument44 pagesSanitation Problem Health SectordeliapatrisaNo ratings yet

- Building Resilient Communities for HealthDocument18 pagesBuilding Resilient Communities for HealthWIlfred bengnwiNo ratings yet

- Health Law AssignmentDocument2 pagesHealth Law AssignmentShubh Dixit0% (1)

- The Private Sector,: Universal Health Coverage and Primary Health CareDocument12 pagesThe Private Sector,: Universal Health Coverage and Primary Health CareJohn Aries CabilingNo ratings yet

- 7c0a PDFDocument17 pages7c0a PDFAngelica RojasNo ratings yet

- Sociology GovernmentDocument6 pagesSociology Governmentgloriabala92No ratings yet

- Primary Health Care 2007 enDocument42 pagesPrimary Health Care 2007 enAC GanadoNo ratings yet

- Ibrahim Halliru T-PDocument23 pagesIbrahim Halliru T-PUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- Community Nursing and Care Continuity LEARNING OUTCOMES After CompletingDocument23 pagesCommunity Nursing and Care Continuity LEARNING OUTCOMES After Completingtwy113100% (1)

- Government's Policy on Public HealthDocument30 pagesGovernment's Policy on Public HealthKrittika PatelNo ratings yet

- Public Health CourseworkDocument12 pagesPublic Health CourseworkAndrew AkamperezaNo ratings yet

- Jakarta Declaration On Leading Health Promotion Into The 21st CenturyDocument4 pagesJakarta Declaration On Leading Health Promotion Into The 21st CenturyWayne Ivan DugayNo ratings yet

- Chapter 7Document9 pagesChapter 7Lawrence Ryan DaugNo ratings yet

- Ijerph 17 04363 v3Document26 pagesIjerph 17 04363 v3biruckNo ratings yet

- Un Platform FinalDocument18 pagesUn Platform FinalAginaya ReinNo ratings yet

- Globalisation and Health: Challenges: Go ToDocument3 pagesGlobalisation and Health: Challenges: Go ToRembrant FernandezNo ratings yet

- Public Health-Its RegulationDocument12 pagesPublic Health-Its RegulationAreeb AhmadNo ratings yet

- KemerutDocument2 pagesKemerutFrance Nathaniel CanaleNo ratings yet

- Building The Primary of The 21st Century: Health Care WorkforceDocument32 pagesBuilding The Primary of The 21st Century: Health Care Workforcelucila falconeNo ratings yet

- National & Sttae Health Care Policy, National Population Policy, AyushDocument52 pagesNational & Sttae Health Care Policy, National Population Policy, Ayushkrishnasree100% (2)

- How Can HealthDocument43 pagesHow Can HealthMaria TricasNo ratings yet

- Recife Declaration 13nov PDFDocument4 pagesRecife Declaration 13nov PDFSá LealNo ratings yet

- SummaryDocument1 pageSummaryVasquez MicoNo ratings yet

- Primary Health Care Approach Outlined in Alma Ata DeclarationDocument5 pagesPrimary Health Care Approach Outlined in Alma Ata DeclarationFlorenze Laiza Donor Lucas100% (1)

- Framework On Integrated People-Centred Health Services (IPCHS)Document23 pagesFramework On Integrated People-Centred Health Services (IPCHS)Merty ReferendumNo ratings yet

- 1 JOOUST FUNDAMENTALS HOME ASSIGNMENTDocument9 pages1 JOOUST FUNDAMENTALS HOME ASSIGNMENTosundwahronnieNo ratings yet

- Savedoff de Ferranti & Smith Et Al 2012 Aspects of Transition To UHCDocument9 pagesSavedoff de Ferranti & Smith Et Al 2012 Aspects of Transition To UHCashakow8849No ratings yet

- National Health Policies 2 ND YearDocument40 pagesNational Health Policies 2 ND YearLIDIYA MOL P VNo ratings yet

- 5 StarDocument13 pages5 StarSofie Hanafiah NuruddhuhaNo ratings yet

- Health needs assessment: Understanding community health prioritiesDocument47 pagesHealth needs assessment: Understanding community health prioritieshanoo777No ratings yet

- Health Care Guide Provides Overview of Systems and ForecastsDocument203 pagesHealth Care Guide Provides Overview of Systems and ForecastsNiro ThakurNo ratings yet

- Hospital AdministrationDocument41 pagesHospital AdministrationAnkita VishwakarmaNo ratings yet

- Towards An Equitable People-Centred Health System For SpainDocument3 pagesTowards An Equitable People-Centred Health System For SpainrevistesperllegirNo ratings yet

- UHC Country Support PDFDocument12 pagesUHC Country Support PDFdiah irfainiNo ratings yet

- Community-Based Health Insurance in Developing CountriesDocument14 pagesCommunity-Based Health Insurance in Developing CountriesRakip MaloskiNo ratings yet

- The Public Private Partnership Has Been Defined by Different Organization As FollowsDocument3 pagesThe Public Private Partnership Has Been Defined by Different Organization As FollowsViru JaniNo ratings yet

- Achieving Better Health for All Through Primary Health CareDocument6 pagesAchieving Better Health for All Through Primary Health CareRem Alfelor100% (1)

- Primary Health Care I 2021Document13 pagesPrimary Health Care I 2021Galakpai KolubahNo ratings yet

- Review of Social Determinants and The Health Divide in The WHO European RegionDocument234 pagesReview of Social Determinants and The Health Divide in The WHO European RegionAdrian ArizmendiNo ratings yet

- Salud 2020Document14 pagesSalud 2020Jorge Mandl StanglNo ratings yet

- Framework On Integrated People Centred Health ServicesDocument12 pagesFramework On Integrated People Centred Health Servicesaperfectcircle7978No ratings yet

- Intersectoral coordination improves health careDocument26 pagesIntersectoral coordination improves health carelimiya vargheseNo ratings yet

- Health Policy of Ethiopia 1993Document11 pagesHealth Policy of Ethiopia 1993Hayleye KinfeNo ratings yet

- Intersectoral Coordination in India For Health Care AdvancementDocument26 pagesIntersectoral Coordination in India For Health Care AdvancementshijoantonyNo ratings yet

- 2.07-4.6 Global Fund Strategic Approach To HSS. WHO ReportDocument50 pages2.07-4.6 Global Fund Strategic Approach To HSS. WHO ReportGeorge KorahNo ratings yet

- HSRA: Fourmula One for Health Reform AgendaDocument3 pagesHSRA: Fourmula One for Health Reform AgendaMadsNo ratings yet

- AhaDocument6 pagesAhaFlorito Jc EspirituNo ratings yet

- The Health Care Delivery SystemDocument34 pagesThe Health Care Delivery SystemFritzie Buquiron67% (3)

- World Health Organization: Discussion PaperDocument65 pagesWorld Health Organization: Discussion PaperJimNo ratings yet

- Assignment: Primary Health Care and Its Components in Detail in The Light of Almata DeclarationDocument11 pagesAssignment: Primary Health Care and Its Components in Detail in The Light of Almata DeclarationfurqanazeemiNo ratings yet

- Unit 8 Task 1Document10 pagesUnit 8 Task 1dk5kbmqg7sNo ratings yet

- The Lancet - Vol. 0376 - 2010.11.27Document79 pagesThe Lancet - Vol. 0376 - 2010.11.27Patty HabibiNo ratings yet

- Un Marco de Resultados de Salud PublicaDocument52 pagesUn Marco de Resultados de Salud PublicaJorge Mandl StanglNo ratings yet

- Icd 10 Code Klinik DR KeluargaDocument6 pagesIcd 10 Code Klinik DR Keluargaferry7765No ratings yet

- Fitness Travel Assessment FormDocument1 pageFitness Travel Assessment Formferry7765No ratings yet

- Modern View On The ChannelsDocument6 pagesModern View On The Channelsferry7765No ratings yet

- Acupuncture ObesityDocument4 pagesAcupuncture Obesityferry7765100% (1)

- Khusha NofashaDocument1 pageKhusha Nofashaferry7765No ratings yet

- Base Line Health Assessment For PrintedDocument3 pagesBase Line Health Assessment For Printedferry7765No ratings yet

- MERS CoV Investigation Guideline Jul13Document40 pagesMERS CoV Investigation Guideline Jul13ferry7765No ratings yet

- Icd 10Document1 pageIcd 10ferry7765No ratings yet

- Acupuncture Case SeriesDocument8 pagesAcupuncture Case Seriesferry7765No ratings yet

- Base Line Health Assessment For PrintedDocument3 pagesBase Line Health Assessment For Printedferry7765No ratings yet

- Daily Report of Doctor ConsultationDocument1 pageDaily Report of Doctor Consultationferry7765No ratings yet

- Care for patients of all ages and communitiesDocument2 pagesCare for patients of all ages and communitiesferry7765No ratings yet

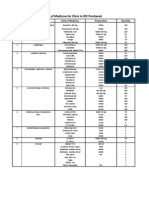

- List of Medicines For Pontianak April 2014Document2 pagesList of Medicines For Pontianak April 2014ferry7765No ratings yet

- SOAP Form For Daily Medical ConsultationDocument2 pagesSOAP Form For Daily Medical Consultationferry7765No ratings yet

- SOAP Form For Daily Medical ConsultationDocument2 pagesSOAP Form For Daily Medical Consultationferry7765No ratings yet

- Patients Registration ListDocument2 pagesPatients Registration Listferry7765No ratings yet

- Koriko LomDocument1 pageKoriko Lomferry7765No ratings yet

- Win. Loader W7Document26 pagesWin. Loader W7Roberto Giner PérezNo ratings yet

- Diabetes Flow SheetDocument2 pagesDiabetes Flow Sheetferry7765No ratings yet

- Contraction of The Five Fingers LU-6, L.I.-3, L.I.-5, SI-4, SJ-2, SJ-3, LIV-3 Lu 5 Si 7Document1 pageContraction of The Five Fingers LU-6, L.I.-3, L.I.-5, SI-4, SJ-2, SJ-3, LIV-3 Lu 5 Si 7ferry7765No ratings yet

- List of Medicines For Pontianak April 2014Document2 pagesList of Medicines For Pontianak April 2014ferry7765No ratings yet

- Young Ti Ying Quan XiDocument6 pagesYoung Ti Ying Quan Xiferry7765No ratings yet

- Stroke LengkapDocument3 pagesStroke Lengkapferry7765No ratings yet

- Daftar Judul Buku Yang Saya PunyaDocument1 pageDaftar Judul Buku Yang Saya Punyaferry7765No ratings yet

- Contraction of The Five Fingers LU-6, L.I.-3, L.I.-5, SI-4, SJ-2, SJ-3, LIV-3 Lu 5 Si 7Document1 pageContraction of The Five Fingers LU-6, L.I.-3, L.I.-5, SI-4, SJ-2, SJ-3, LIV-3 Lu 5 Si 7ferry7765No ratings yet

- Participant ID Date Received 1st Keying Assigned To 2nd Keying Assigned To Problems Solutions NotesDocument1 pageParticipant ID Date Received 1st Keying Assigned To 2nd Keying Assigned To Problems Solutions Notesferry7765No ratings yet

- Alamat P CareDocument1 pageAlamat P Careferry7765No ratings yet

- Time Sheet 21 April 2014 To 20 May 2014Document1 pageTime Sheet 21 April 2014 To 20 May 2014ferry7765No ratings yet

- Khusha NofashaDocument1 pageKhusha Nofashaferry7765No ratings yet

- Jurnal DMDocument13 pagesJurnal DMidaNo ratings yet

- Golden Berry Bioautography Reveals Antibacterial CompoundsDocument11 pagesGolden Berry Bioautography Reveals Antibacterial CompoundsGeraldineMoletaGabutinNo ratings yet

- Third Quarter Summative Test No. 4 EnglishDocument3 pagesThird Quarter Summative Test No. 4 EnglishJoanaNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus British English Intermediate b1 b2 GroupDocument4 pagesCoronavirus British English Intermediate b1 b2 GroupAngel AnitaNo ratings yet

- Studies in History and Philosophy of Science: Eliminative Abduction in MedicineDocument8 pagesStudies in History and Philosophy of Science: Eliminative Abduction in MedicineFede FestaNo ratings yet

- Canine Disobedient, Unruly and ExcitableDocument5 pagesCanine Disobedient, Unruly and ExcitableBrook Farm Veterinary CenterNo ratings yet

- Terminologia LatinaDocument7 pagesTerminologia LatinaКонстантин ЗахарияNo ratings yet

- VSL TB Workplace Policy ProgramDocument3 pagesVSL TB Workplace Policy ProgramAlexander John AlixNo ratings yet

- Marking Scheme: Biology Paper 3Document4 pagesMarking Scheme: Biology Paper 3sybejoboNo ratings yet

- Pharmacology - Tot - NR 6classid S.F.ADocument74 pagesPharmacology - Tot - NR 6classid S.F.AcorsairmdNo ratings yet

- Word Parts Dictionary, Prefixes, Suffixes, Roots and Combining FormsDocument237 pagesWord Parts Dictionary, Prefixes, Suffixes, Roots and Combining Formslaukings100% (9)

- Ananda Zaren - Core Elements of The Materia Medica of The Mind - Vol IDocument101 pagesAnanda Zaren - Core Elements of The Materia Medica of The Mind - Vol Ialex100% (2)

- Organ Transplantatio1Document26 pagesOrgan Transplantatio1Bindashboy0No ratings yet

- EXP 6 - Fecal Coliform Test - StudentDocument8 pagesEXP 6 - Fecal Coliform Test - StudentAbo SmraNo ratings yet

- How Can Women Make The RulesDocument0 pagesHow Can Women Make The Ruleshme_s100% (2)

- Homeoapthy For InfantsDocument9 pagesHomeoapthy For Infantspavani_upNo ratings yet

- ShaylaDocument3 pagesShaylaapi-530728661No ratings yet

- M1 ReadingwritingDocument8 pagesM1 ReadingwritingChing ServandoNo ratings yet

- PMO - Pasteurized Milk OrdinanceDocument340 pagesPMO - Pasteurized Milk OrdinanceTato G.k.No ratings yet

- Dangers of Excess Sugar ConsumptionDocument2 pagesDangers of Excess Sugar ConsumptionAIDEN COLLUMSDEANNo ratings yet

- 13 Levels of AssessmentDocument11 pages13 Levels of AssessmentCatherine Cayda dela Cruz-BenjaminNo ratings yet

- 10 DOH Approved Herbal Medicine: Prepared By: Washington, Luis D. Student Nurse BSN 2H-DDocument11 pages10 DOH Approved Herbal Medicine: Prepared By: Washington, Luis D. Student Nurse BSN 2H-DLuis WashingtonNo ratings yet

- Soal BAHASA INGGRIS - X - KUMER - PAKET 2Document13 pagesSoal BAHASA INGGRIS - X - KUMER - PAKET 2Agus SuhendraNo ratings yet

- Nat Ag Winter Wheat in N Europe by Marc BonfilsDocument5 pagesNat Ag Winter Wheat in N Europe by Marc BonfilsOrto di CartaNo ratings yet

- AIPG Paper CorrectedDocument42 pagesAIPG Paper CorrectedbrihaspathiacademyNo ratings yet

- Types of Feeding TubesDocument8 pagesTypes of Feeding TubesElda KuizonNo ratings yet

- A Novel Lymphocyte Transformation Test (LTT-MELISAR) For Lyme BorreliosisDocument8 pagesA Novel Lymphocyte Transformation Test (LTT-MELISAR) For Lyme Borreliosisdebnathsuman49No ratings yet

- The Impact of Life Cycles on Family HealthDocument27 pagesThe Impact of Life Cycles on Family Healthmarcial_745578124No ratings yet

- Diane Pills Drug StudyDocument4 pagesDiane Pills Drug StudyDawn EncarnacionNo ratings yet

- Detailed Project Report (DPR) :model Template: For NHB Scheme No.1 For AonlaDocument136 pagesDetailed Project Report (DPR) :model Template: For NHB Scheme No.1 For AonlajainendraNo ratings yet

- Workin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherFrom EverandWorkin' Our Way Home: The Incredible True Story of a Homeless Ex-Con and a Grieving Millionaire Thrown Together to Save Each OtherNo ratings yet

- The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationFrom EverandThe Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (32)

- Uncontrolled Spread: Why COVID-19 Crushed Us and How We Can Defeat the Next PandemicFrom EverandUncontrolled Spread: Why COVID-19 Crushed Us and How We Can Defeat the Next PandemicNo ratings yet

- When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfFrom EverandWhen Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (36)

- The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationFrom EverandThe Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American MigrationRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (19)

- Poor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global PovertyFrom EverandPoor Economics: A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global PovertyRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (263)

- Summary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness, and Healing in a Toxic Culture By Gabor Maté MD & Daniel Maté: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public HousingFrom EverandHigh-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public HousingNo ratings yet

- Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in CrisisFrom EverandHillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in CrisisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4276)

- Fucked at Birth: Recalibrating the American Dream for the 2020sFrom EverandFucked at Birth: Recalibrating the American Dream for the 2020sRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (172)

- Do You Believe in Magic?: The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative MedicineFrom EverandDo You Believe in Magic?: The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative MedicineNo ratings yet

- Epic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients.From EverandEpic Measures: One Doctor. Seven Billion Patients.Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (13)

- The Wisdom of Plagues: Lessons from 25 Years of Covering PandemicsFrom EverandThe Wisdom of Plagues: Lessons from 25 Years of Covering PandemicsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Deaths of Despair and the Future of CapitalismFrom EverandDeaths of Despair and the Future of CapitalismRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (30)

- Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthFrom EverandHeartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (269)

- Nickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in AmericaFrom EverandNickel and Dimed: On (Not) Getting By in AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (186)

- Not a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaFrom EverandNot a Crime to Be Poor: The Criminalization of Poverty in AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (37)

- When Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfFrom EverandWhen Helping Hurts: How to Alleviate Poverty Without Hurting the Poor . . . and YourselfRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (126)

- Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthFrom EverandHeartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on EarthRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (188)

- Sons, Daughters, and Sidewalk Psychotics: Mental Illness and Homelessness in Los AngelesFrom EverandSons, Daughters, and Sidewalk Psychotics: Mental Illness and Homelessness in Los AngelesNo ratings yet

- Charity Detox: What Charity Would Look Like If We Cared About ResultsFrom EverandCharity Detox: What Charity Would Look Like If We Cared About ResultsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (9)

- Alienated America: Why Some Places Thrive While Others CollapseFrom EverandAlienated America: Why Some Places Thrive While Others CollapseRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (35)