Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ngos: What'S in An Acronym?

Uploaded by

ptlabadieOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ngos: What'S in An Acronym?

Uploaded by

ptlabadieCopyright:

Available Formats

NGOs: What's In An Acronym?

[1]

Mark B. Ginsburg

Institute for International Studies in Education

School of Education, University of Pittsburgh

In recent years nongovernmental organizations or NGOs have become increasingly

visible and active in various sectors of social life, including education. As Edwards and

Hulme (1996) report, there has been a "[r]apid growth in NGO numbers ()

accompanied in some countries () by a trend toward expansion in the size of

individual NGOs and NGO programs" (p. 962). At the same time, NGOs have received

greater attention in government and international organization reports and policy

documents, as well as in scholarly literature. In this burgeoning literature, NGOs are

characterized and evaluated in quite different ways. Sometimes the acronym, "NGO,"

seems to serve as shorthand for "New Great Organization" and other times it appears to

refer to "Never Good Organization." [2] One might summarize the case for and against

NGOs by way of a parody of Shakespeare's statement about roses: an NGO by any other

name would smell as sweet - or as rancid.

Different Cases?

Part of the reason for the contradictory representations of NGOs is that they constitute a

heterogeneous set of institutions, and not just because of the different sectors in which

they work or the gender, racial/ethnic, and social class characteristics of participants

(e.g., see Stromquist, 1996).[3] They include: (1) grassroots operations intricately linked

to social movements aimed at challenging and transforming unequal social structures;

(2) nonprofit businesses run by "professionals" that provide work and income

opportunities for the disadvantaged in an effort to incorporate them in extant political

economic arrangements and (3) some NGOs are locally-based institutions that operate

on a shoe-string budget derived from the resources of those involved, while others are

international entities with sizable budgets built from grants and contracts from

international organizations (e.g., development banks, UN agencies, and foundations) as

well as national governments (foreign as well as domestic to the locale of any particular

project being undertaken). [4]

Different Paradigms

NGOs are also characterized differently in the literature because authors bring different

perspectives to their analytical task. Thus, even when scholars are examining the same

NGO or similar types of NGOs, they may emphasize different elements of their

operations and they may conclude with contrasting appraisals. For instance, Carroll

(1992) describes how NGOs in Latin America contribute invaluable, practical assistance

to local grassroots groups involved in economic development activities, while Petras

(1997) portrays similar NGOs in Latin America as "competing with socio-political

movements for the allegiance of local leaders and activist communities" (p. 10) and

linking "foreign funders with local labor ([via] self-help micro-enterprises) to facilitate

the continuation of the neo-liberal regime" (p. 25).

The difference in perspectives is to some extent captured by typologies or mappings of

social theory paradigms (e.g., Epstein, 1986; Ginsburg, 1991; Paulston, 1977 and 1996;

2002 Current Issues in Comparative Education, Teachers College, Columbia University, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Current Issues in Comparative Education, Vol.1(1)

29

Mark B. Ginsburg

Stromquist, 1995; Morrow & Torres, 1995). For example, analysts employing equilibrium

perspectives (e.g., functionalism) tend to paint a different portrait of NGOs than those

using the lens of conflict theory (whether feminist, Marxist, anti-racist, anti-imperialist).

[5]

Privatized versus Public Democracy

However, analysts--even those who are grounded in similar paradigms--may depict and

evaluate NGOs differently because of differences in their conceptions of space available

for "democratic" participation within the state versus within civil society. [6] For some

authors, NGOs are lauded because they constitute "an integral component of civil

society and an essential counterweight to state power" (Edwards & Hulme, 1996, p. 962).

For example, Petras (1997) notes that NGOs "during their earlier history in the 1970s

were active in providing humanitarian support to the victims of the military

dictatorship[s] and denouncing human rights violations" (pp. 10-11).

Such enthusiasm for NGOs' efforts to carve out more space for civil society may, in

general, make sense in the context of authoritarian regimes. [7] But in the context of (at

least potentially) democratic political systems, one would applaud the increasing role of

NGOs only to the extent that one viewed the state or the public sector as unresponsive

or inefficient. In the writings of some conflict theorists the state is portrayed as meeting

the needs of national or global capitalists or other dominant groups, and thus not

responsive to the needs of workers, women, and minority racial/ethnic groups (e.g.,

Althusser, 1971), while in neo-liberal versions of equilibrium theory the state is

characterized as inefficient because government bureaucracies are not subject to market

forces and profit motives (see Edwards and Hulme, 1996, p. 961). [8]

In contrast, one might be more inclined to criticize the role of (certain) NGOs to the

extent that one perceived the state and the public sector as a desirable or the most likely

terrain on which democracy can be achieved. [9] Edwards & Hulme (1996, p. 966), for

instance, report that NGOs' increasing dependence of funding from "foreign" donors

(e.g., other governments, UN agencies, corporate and other private foundations) and

pose the questions of whether this represents a "strengthening of civil society or ()

merely an attempt to shape civil society in ways that external actors believe [are]

desirable." [10] In this sense, NGOs are likely to be less accountable to the people in

local, state/provincial, and national communities than governments that at least to some

extent can be characterized as democratic--in procedural and/or substantive terms. [11]

As Petras (1997) explains, some "NGOs depoliticize sectors of the population () [and]

undermine democracy by taking social programs out of the hands of the local people

and their elected officials to create dependence on non-elected, overseas () [or] locally

anointed officials" (p. 13).

While those subscribing to each of these perspectives may want to claim that only their

viewpoint operates with democracy as a core value, it seems more appropriate to say

that each side bases its arguments on a different conception of democracy and

citizenship--privatized versus public. These conceptions, at least within European

cultural traditions, can be traced to the writings of John Locke and Jean-Jacques

Rousseau. According to Sehr (1997), "privatized democracy minimizes the role of

30

November`15, 1998

NGOs: Whats In An Acronym?

ordinary citizens as political actors who can shape their collective destiny through

[direct] participation with other in public life" (p. 4). This privatized notion of

democracy is based on: (1) "fears about the people's ability to govern itself" (p. 32) in a

manner that would "effect the 'mutual preservation of lives, liberties, and estates"(p. 32)

and (2) a belief in egotistic individualism, and a glorification of materialism and

consumerism as keys to personal happiness and fulfillment" (p. 4). [12] In contrast,

"public democracy sees people's participation in public life as the essential ingredient

in democratic government. Public participation arises out of an ethic of care and

responsibility, not only for oneself as an isolated individual, but for one's fellow citizens

as co-builders and co-beneficiaries of the public good" (p. 4).

Conclusion

In this essay I have answered the question--What's in an acronym (specifically NGOs)?-by saying that it depends (1) on which case one examines, (2) on which paradigm (e.g.,

equilibrium or conflict) one brings to the examination, and (3) on which model of

democracy (privatized or public) one values. While perhaps in a post-modern era such a

conclusion (viz., "it depends") might merely be accepted as the "reality," I want to

encourage us to go beyond merely recognizing multiple "realities" and develop ways for

struggling "politically" (Ginsburg, Kamat, Raghu, & Weaver, 1995) around these issues.

[13] This is because the way we (and others) come to understand and act on these issues

in relation to our work with, in, and on NGOs is likely to have real consequences for the

quality of life, making life on this planet sweeter and/or more rancid.

Notes

[1] This paper is an elaboration of a presentation made at part of a symposium, "Are

NGOs Overrated? Critical Reflections on the Expansion and Institutionalization of

NGOs," at the Comparative and International Education Society annual meeting,

Buffalo, New York, 18-22 March 1998.

[2] It is curious that in English the acronym for nongovernmental organizations is not

"NO" rather than NGO, though perhaps this would carry too negative of a connotation.

Of course, the acronym, NGO, is not really translatable into other languages, even those

using the same alphabet. For example, in Spanish the acronym would be (ONG or ON)

for Organzaciones Nogovernmentales.

[3] Kamat (1998) observes in her study of activists involved in rural India that some

groups actually create two parallel organizations--one for social change efforts involving

political protest, lobbying, and electoral work and one that seeks grants from

government and other sources to support economic enterprise initiatives.

[4] Thus, "[i]n reality non-governmental organizations are not non-governmental () [in

that they] receive funds from overseas governments or work as private contractors"

(Petras, 1997, p. 13). Interestingly, some NGOs self-consciously eschew funding from

"foreign" sources, because of fear of their corruptive influence, but at the same time

secure funding from provincial and national governments or foundations without a

parallel concern for being corrupted by such funding sources (Zachariah &

Sooryamoorthy, 1994).

Current Issues in Comparative Education, Vol.1(1)

31

Mark B. Ginsburg

[5] We should be cautious about adopting too overly-deterministic a perspective. As

with the case of studying imperialism and colonialism, when investigating NGOs, there

is a need to pay attention to how individual and collective actors may engage in

transactions, even within unequal power relations, that yield other consequences than

might be expected if one assumed that social structures completely determine human

thought and action (see Ginsburg & Clayton, 1998).

[6] I would distinguish my focus here from that discussed in Edwards & Hulme (1996, p.

965) concerning whether NGOs in fact promote involvement in "democratic" political

systems or whether NGOs function internally in a democratic manner.

[7] I say "may make sense" if such action within civil society involved struggle to

democratize local, national, and global states (and economies) rather than initiatives to

create havens from the heartless world of the state apparatus, which would remain

controlled by political economic elites.

[8] It may also be that those espousing neo-liberal or conservative equilibrium views

prefer using the NGO route because, at least from the perspective of some elites, "too

much" space has been opened up in the political system for workers and other

oppressed groups to make demands for and shape the character of public services. And

as Petras (1997, p. 11) observes: "There is a direct relationship between the growth of

social movements challenging the neo-liberal model and the effort to subvert them by

creating alternative forms of social action through the NGOs."

[9] Moreover, foreign government and international organization support for NGOs

must be seen in relation to structural adjustment programs, privatization projects, and

other moves to delegitimate the state and destroy public sector employment (and the

relatively better, unionized jobs associated with it). And domestic government funding

for NGOs--representing a form of contracting out of public service work - can be seen as

in line with a similar philosophy regarding the state and the economy. According to

Petras (1997, p. 13): "In practice, 'non-governmental' translates into anti-public-spending

activities, freeing the bulk of funds for neo-liberals to subsidize export capitalists while

small sums trickle from the government to NGOs."

[10] Of course, the external funding sources do not comprise a homogeneous set with

respect to the power they wield or the interests they might be seen to serve.

[11] Here I follow Highland (1995, p. 67) in conceiving of a power structure as

democratic to the extent that all person "have equal effective rights in the determination

of decisions to which they are subject." Furthermore, Highland (1995, p. 2) notes, this

necessitates "both procedural entitlements to participate in a decision-making process

and adequate access to a wide range of [material and symbolic] resources that would

enable a person to utilize her or his procedural entitlements."

[12] Note that for Locke human life and liberties are included along with estates as forms

of "property."

[13] There is perhaps some irony that the only "reality" acknowledged by many post-

32

November`15, 1998

NGOs: Whats In An Acronym?

modernists is that there are multiple realities.

References

Althusser, L. (1971). Lenin and philosophy, and other essays (Brewster, B. [Trans.]). New

York: Monthly Review Press.

Carroll, T. (1992). Intermediary NGOs: The supporting link in grassroots development. New

York: Kumarian Press.

Edwards, M. & Hulme, D. (1996). Too close for comfort? The impact of official aid on

nongovernmental organizations. World Development 24(6), 961-73.

Epstein, E. (1986). Currents left and right: Ideology in comparative education. In P.

Altbach, & G. Kelly (Eds.), New approaches to comparative education (pp.233-59). Chicago:

University of Chicago Press.

Ginsburg, M. (1991). Educational reform: Social struggle, the state, and the world

economic system. In M. Ginsburg (Ed.), Understanding educational reform in global context:

Economy, ideology and the state (pp.3-48). New York: Garland Publishing.

Ginsburg, M. & Clayton, T. (1998). Imperialism and colonialism. In D. Levinson, A.

Sadovnik, & P. Cookson (Eds.), Education and sociology: An encyclopedia. New York:

Garland Publishing.

Ginsburg, M., Kamat, S., Raghu, R., & Weaver, J. (1995). Educators and politics:

Interpretations, involvement, and implications. In M. Ginsburg (Ed.), The politics of

educators' work and lives (pp.3-54). New York: Garland Publishing.

Highland, J. (1995). Democratic theory: The philosophical foundations. Manchester:

Manchester University Press.

Kamat, S. (1998). Development hegemony: An analysis of grassroots formations and the

state in Maharashtra, India. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh.

Morrow, R. & Torres, C. (1995). Social theory and education. Albany, NY: State University

of New York Press.

Paulston, R. (1977). Social and educational change. Comparative Education Review, 21

(2/3), 370-95.

Paulston, R. (1996). Mapping visual culture in comparative education discourse.

Compare, 27(2), 117-152.

Petras, J. (1997). Imperialism and NGOs in Latin America. Monthly Review, 49(7), 10-33.

Sehr, D. (1997). Education for public democracy. Albany, NY: State University of New York

Press.

Current Issues in Comparative Education

33

Mark B. Ginsburg

Stromquist, N. (1995). Gender and power in education. Comparative Education Review,

39(4), 423-54.

Stromquist, N. (1996). Mapping gendered spaces in third world educational

interventions. In R. Paulston (Ed.), Social cartography: Mapping ways of seeing social and

educational change (pp.223-47). New York: Garland.

Zachariah, M. & Sooryamoorthy, R. (1994). Social science for social revolution? Achievement

and dilemmas of a development movement: The Kerala Sastra Sahitya Parishad. New Delhi:

Vistaar Publications.

34

November`15, 1998

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Municipal and International LawDocument12 pagesMunicipal and International LawAartika SainiNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Demand Letter To The Department of JusticeDocument4 pagesDemand Letter To The Department of JusticeGordon Duff100% (1)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Fundamental Powers of the State: Police, Eminent Domain, TaxationDocument2 pagesFundamental Powers of the State: Police, Eminent Domain, TaxationÄnne Ü Kimberlie81% (74)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- VA Bar ComplaintDocument13 pagesVA Bar ComplaintABC7 WJLANo ratings yet

- Neil Andrews PDFDocument37 pagesNeil Andrews PDFpmartinezbNo ratings yet

- St. Aviation Services Co., Pte, LTD v. Grand AirwaysDocument2 pagesSt. Aviation Services Co., Pte, LTD v. Grand AirwaysYodh Jamin OngNo ratings yet

- Southeast Mindanao Gold Mining Corp vs. Balite Portal MiningDocument2 pagesSoutheast Mindanao Gold Mining Corp vs. Balite Portal MiningRob3rtJohnson100% (2)

- Sandiganbayan Jurisdiction Over UP Student RegentDocument4 pagesSandiganbayan Jurisdiction Over UP Student RegentJ CaparasNo ratings yet

- Title: Death Penalty in The Philippines: Never AgainDocument7 pagesTitle: Death Penalty in The Philippines: Never AgainJomarNo ratings yet

- Poetry in Motion A Collection of Short Poetry For The Modern SoulDocument1 pagePoetry in Motion A Collection of Short Poetry For The Modern SoulptlabadieNo ratings yet

- Practice Questions For CH 12Document1 pagePractice Questions For CH 12ptlabadieNo ratings yet

- Colonial StateDocument1 pageColonial StateptlabadieNo ratings yet

- PoemDocument1 pagePoemptlabadieNo ratings yet

- Practice Questions For CH 12Document1 pagePractice Questions For CH 12ptlabadieNo ratings yet

- September 15 Notes Health 101Document86 pagesSeptember 15 Notes Health 101ptlabadieNo ratings yet

- Police Check PDFDocument8 pagesPolice Check PDFptlabadieNo ratings yet

- Aphex Twin - Avril 14thDocument3 pagesAphex Twin - Avril 14thdiminuta.netNo ratings yet

- Bridget's Pics For Hip HopDocument2 pagesBridget's Pics For Hip HopptlabadieNo ratings yet

- Presentation MboDocument4 pagesPresentation MboptlabadieNo ratings yet

- 10 1 1 259 4232Document60 pages10 1 1 259 4232Anonymous CzfOUjdNo ratings yet

- Carlos Eduardo Lopez Romero - US IndictmentDocument17 pagesCarlos Eduardo Lopez Romero - US IndictmentMXNo ratings yet

- Role of Judiciary in Environmental ProtectionDocument7 pagesRole of Judiciary in Environmental ProtectionRASHMI KUMARINo ratings yet

- 121 CrimPro NotesDocument208 pages121 CrimPro NotesMaximine Alexi SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Classical Criminology HandoutsDocument3 pagesClassical Criminology HandoutsLove BachoNo ratings yet

- Anand Yadav Pro 1Document23 pagesAnand Yadav Pro 1amanNo ratings yet

- Comprehensive Barangay Youth Development PlanDocument4 pagesComprehensive Barangay Youth Development PlanVergel Cabanting De OcampoNo ratings yet

- Zizek On Post PoliticsDocument8 pagesZizek On Post PoliticsxLKuv5XGjSfcNo ratings yet

- Respondent 2010 D M Harish Memorial Moot Competition PDFDocument41 pagesRespondent 2010 D M Harish Memorial Moot Competition PDFBrijeshNo ratings yet

- Republic Vs CA GR119288Document8 pagesRepublic Vs CA GR119288AnonymousNo ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction On Marketing Mix of Lux SoapDocument14 pagesCustomer Satisfaction On Marketing Mix of Lux SoapJeffrin Smile JNo ratings yet

- SD - Formulas de Cálculo de ImpostoDocument83 pagesSD - Formulas de Cálculo de ImpostoThaís DalanesiNo ratings yet

- Understanding Parole Eligibility, Qualifications and Review ProcessDocument9 pagesUnderstanding Parole Eligibility, Qualifications and Review ProcesskemerutNo ratings yet

- NorthWestern University Social Media MarketingDocument1 pageNorthWestern University Social Media MarketingTrav EscapadesNo ratings yet

- 11 Social Action: Concept and PrinciplesDocument18 pages11 Social Action: Concept and PrinciplesAditya VermaNo ratings yet

- Practice of Law RequirementsDocument2 pagesPractice of Law RequirementsJosephine BercesNo ratings yet

- You Incorporated - 22.08.18Document41 pagesYou Incorporated - 22.08.18inestempleNo ratings yet

- Evidence - Disputable Presumptions Can They Be Weighed?: Victor H. LaneDocument2 pagesEvidence - Disputable Presumptions Can They Be Weighed?: Victor H. LaneJeric LepasanaNo ratings yet

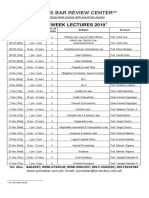

- 2019 Schedule of Preweek LecturesDocument1 page2019 Schedule of Preweek LecturesVioletNo ratings yet

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument3 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationDang Joves BojaNo ratings yet

- Corpuz vs. PeopleDocument2 pagesCorpuz vs. PeopleAli NamlaNo ratings yet