Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ijirt100202 Paper PDF

Uploaded by

DrMadhuravani PeddiOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ijirt100202 Paper PDF

Uploaded by

DrMadhuravani PeddiCopyright:

Available Formats

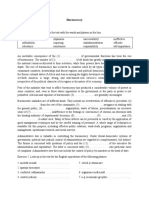

2014 IJIRT | Volume 1 Issue 5 | ISSN : 2349-6002

ONLINE SOCIAL NETWORKS CONSEQUENCE AND ALTERNATION

Amula Sreelatha1, B. Madhuravani2

1

M.Tech, CSE Dept, MLRIT, Hyderabad

2

M.Tech, (PhD), Asst. Professor, MLRIT, Hyderabad

Abstract Different communities of computer science

researchers have framed the OSN privacy problem as one

of surveillance, institutional or social privacy. In tackling

these problems they have also treated them as if they were

independent. We argue that the different privacy problems

are entangled and that research on privacy in OSNs would

benefit from a more holistic approach. Privacy is one of the

friction points that emerge when communications get

mediated in Online Social Networks (OSNs). In this article,

we first provide an introduction to the surveillance and

social privacy perspectives emphasizing the narratives that

inform them, as well as their assumptions, goals and

methods. We then juxtapose the differences between these

two approaches in order to understand their

complementary, and to identify potential integration

challenges as well as research questions that so far have been

left unanswered.

I.

INTRODUCTION

Can users have reasonable expectations of privacy in

Online Social Networks (OSNs)? Media reports,

regulators and researchers have replied to this question

affirmatively. Even in the transparent world created by

the Facebooks, LinkedIns and Twitters of this world,

users have legitimate privacy expectations that may be

violated [9], [11]. Researchers from different subdisciplines in computer science have tackled some of the

problems that arise in OSNs, and proposed a diverse

range of privacy solutions. These include software tools

and design principles to address OSN privacy issues.

Each of these solutions is developed with a specific type

of user, use, and privacy problem in mind. This has had

some positive effects: we now have a broad spectrum of

approaches to tackle the complex privacy problems of

OSNs. At the same time, it has led to a fragmented

landscape of solutions that address seemingly unrelated

problems. As a result, the vastness and diversity of the

field remains mostly inaccessible to outsiders, and at

times even to researchers within computer science who

are specialized in a specific privacy problem.

Hence, one of the objectives of this paper is to put these

approaches to privacy in OSNs into perspective. We

IJIRT 100202

distinguish three types of privacy problems that researchers

in computer science tackle. The first approach addresses the

surveillance problem that arises when the personal

information and social interactions of OSN users are

leveraged by governments and service providers. The

second this article appears in the IEEE Security & Privacy

11(3):29-37, May/June 2013. This is the authors version of

the paper. The magazine version is available at:

http://www.computer.org/ csdl/mags/ sp/2013/03/msp20130

30029-abs.html approach addresses those problems that

emerge through the necessary renegotiation of boundaries as

social interactions get mediated by OSN services, in short

called social privacy.

The third approach addresses problems related to users

losing control and oversight over the collection and

processing of their information in OSNs, also known as

institutional privacy [17]. Each of these approaches

abstracts away some of the complexity of privacy in OSNs

in order to focus on more solvable questions. However,

researchers working from different perspectives differ not

only in what they abstract, but also in their fundamental

assumptions about what the privacy problem is.

Thus, the surveillance, social privacy, and institutional

privacy problems end up being treated as if they were

independent phenomena.

II.

PROBLEM STATEMENT

The existing work could model and analyze access control

requirements with respect to collaborative authorization

management of shared data in OSNs. The need of joint

management for data sharing, especially photo sharing, in

OSNs has been recognized by the recent work provided a

solution for collective privacy management in OSNs. Their

work considered access control policies of a content that is

co-owned by multiple users in an OSN, such that each coowner may separately specify her/his own privacy

preference for the shared content. We distinguish three types

of privacy problems that researchers in computer science

tackle. The first approach addresses the surveillance

problem that arises when the personal information and

social interactions of OSN users are leveraged by

governments and service providers. The second approach

INTERNATONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN TECHNOLOGY

93

2014 IJIRT | Volume 1 Issue 5 | ISSN : 2349-6002

addresses those problems that emerge through the

necessary renegotiation of boundaries as social

interactions get mediated by OSN services, in short called

social privacy. The third approach addresses problems

related to users losing control and oversight over the

collection and processing of their information in OSNs,

also known as institutional privacy.

Advantages of The System

Computation cost is low.

Scalability is high

User friendly

III.

SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT

The Social Privacy:

Social privacy relates to the concerns that users raise and

to the harms that they experience when technologically

mediated communications disrupt social boundaries. The

users are thus consumers of these services. They spend

time in these (semi-)public spaces in order to socialize

with family and friends, get access to information and

discussions, and to expand matters of the heart as well as

those of belonging. That these activities are made public

to friends or a greater audience is seen as a crucial

component of OSNs. In Access Control, solutions that

employ methods from user modeling aim to develop

meaningful privacy settings that are intuitive to use, and

that cater to users information management needs.

Surveillance:

With respect to surveillance, the design of PETs starts

from the premise that potentially adversarial entities

operate or monitor OSNs. These have an interest in

getting hold of as much user information as possible,

including user-generated content (e.g., posts, pictures,

private messages) as well as interaction and behavioral

data (e.g., list of friends, pages browsed, likes). Once an

adversarial entity has acquired user information, it may

use it in unforeseen ways and possibly to the

disadvantage of the individuals associated with the data.

Institutional Privacy:

The way in which personal control and institutional

transparency requirements, as defined through legislation,

are implemented has an impact on both surveillance and

social privacy problems, and vice versa. institutional

privacy studies ways of improving organizational data

management practices for compliance, e.g., by developing

mechanisms for information flow control and

accountability in the back end. The challenges identified

in this paper with integrating surveillance and social

IJIRT 100202

privacy are also likely to occur in relation to institutional

privacy, given fundamental differences in assumptions and

research methods.

Approach To Privacy As Protection:

The goal of PETs (Privacy Enhancing Technologies) in

the context of OSNs is to enable individuals to engage with

others, share, access and publish information online, free

from surveillance and interference. Ideally, only information

that a user explicitly shares is available to her intended

recipients, while the disclosure of any other information to

any other parties is prevented. Furthermore, PETs aim to

enhance the ability of a user to publish and access

information on OSNs by providing her with means to

circumvent censorship.

IV.

RELATED WORK

We investigated two forms of privacy-related behavior: selfreported adoption of privacy preserving strategies and selfreported past release of personal information. We

investigated the use of several privacy technologies or

strategies and found a multifaceted picture. Usage of

specific technologies was consistently lowfor example,

67.0 percent of our sample never encrypted their emails,

82.3 percent never put a credit alert on their credit report,

and 82.7 percent never removed their phone numbers from

public directories. However, aggregating, at least 75 percent

did adopt at least one strategy or technology, or otherwise

took some action to protect their privacy (such as

interrupting purchases before entering personal information

or providing fake information in forms).

These results indicate a multifaceted behavior: because

privacy is a personal concept, not all individuals protect it

all the time. Nor do they have the same strategies or

motivations. But most do act. Several questions investigated

the subjects reported release of various types of personal

information (ranging from name and home address to email

content, social security numbers, or political views) in

different contexts (such as interaction with merchants,

raffles, and so forth). For example, 21.8 percent of our

sample admitted having revealed their social security

numbers for discounts or better services or

recommendations, and 28.6 percent gave their phone

numbers. A cluster analysis of the relevant variables

revealed two groups, one with a substantially higher degree

of information revelation and risk exposure along all

measured dimensions (64.7 percent) than the other (35.3

percent). We observed the most significant differences

between the two clusters in past behavior regarding the

INTERNATONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN TECHNOLOGY

94

2014 IJIRT | Volume 1 Issue 5 | ISSN : 2349-6002

release of social security numbers and descriptions of

professional occupation, and the least significant

differences for name and nonprofessional interests.

When comparing privacy attitudes with reported

behavior, individuals generic attitudes might often

appear to contradict the frequent and voluntary release of

personal information in specific situations.710 However,

from a methodological perspective we should investigate

how psychological attitudes relate to behavior under the

same scenario conditions (or frames), because a persons

generic attitude might be affected by different factors than

those influencing her conduct in a specific situation.17

Under more specific frames, we found supporting

evidence for an attitude/behavior dichotomy. For

example, we compared stated privacy concerns to

ownership of supermarket loyalty cards. In our sample

87.5 percent of individuals with high concerns toward the

collection of offline identifying information (such as

name and address) signed up for a loyalty card using their

real identifying information. Furthermore, we asked

individuals about specific privacy concerns they have

(participants could provide answers in a free text format)

and found that of those who were particularly concerned

about credit card fraud and identity theft only 25.9 percent

used credit alert features. In addition, of those respondents

that suggested elsewhere in the survey that privacy should

be protected by each individual with the help of

technology, 62.5 percent never used encryption, 43.7

percent do not use email filtering technologies, and 50.0

percent do not use shredders for documents to avoid

leaking sensitive information.

Analysis: these dichotomies do not imply irrationality or

reckless behavior. Individuals make privacy-sensitive

decisions based on multiple factors, including (but not

limited to) what they know, how much they care, and how

costly and effective their actions they believe can be.

Although our respondents displayed sophisticated privacy

attitudes and a certain level of privacy-consistent

behavior, their decision process seems affected by

incomplete information, bounded rationality, and

systematic psychological deviations from rationality.

Armed with incomplete information

Survey questions about respondents knowledge of

privacy risks and modes of protection (from identity theft

and third-party monitoring to privacy-enhancing

technologies and legal means for privacy protection)

produced nuanced results. The evidence points to an

alternation of awareness and unawareness from one

IJIRT 100202

scenario to the other18,19 (a cluster of 31.9 percent of

respondents displayed high unawareness of simple risks

across most scenarios).

On the one hand, 83.5 percent of respondents believe that it

is most or very likely that information revealed during an ecommerce transaction would be used for marketing

purposes; 76.0 percent believe that it is very or quite likely

that a third party can monitor some details of usage of a file

sharing client; and 26.4 percent believe that it is very or

quite likely that personal information will be used to vary

prices during future purchases. On the other hand, most of

our subjects attributed incorrect values to the likelihood and

magnitude of privacy abuses. In a calibration study, we

asked subjects several factual questions about values

associated with security and privacy scenarios.

Participants had to provide a 95-percent confidence interval

(that is a low and high estimate so that they are 95 percent

certain that the true value will fall within these limits) for

specific privacy-related questions. Most answers greatly

under or overestimated the likelihood and consequences of

privacy issues. For example, when we compared estimates

for the number of people affected by identity theft

(specifically for the US in 2003) to data from public sources

(such as US Federal Trade Commission), we found that 63.8

percent of our sample set their confidence intervals too

narrowlyan indication of overconfidence.20 of those

individuals, 73.1 percent underestimated the risk of

becoming a victim of identity theft.

Similarly, although respondents realize the risks associated

with links between different pieces of personal data, they

are not fully aware of how powerful those links are. For

example, when asked, Imagine that somebody does not

know you but knows your date of birth, sex, and zip code.

What do you think the probability is that this person can

uniquely identify you based on those data?, 68.6 percent

answered that the probability was 50 percent or less (and

45.5 percent of respondents believed that probability to be

less than 25 percent). According to Carnegie Mellon

University researcher Latanya Sweeney,21 87 percent of the

US population may be uniquely identified with a 5-digit zip

code, birth date, and sex.

In addition, 87.5 percent of our sample claimed not to know

what Echelon (an alleged network of government

surveillance) is; 73.1 percent claimed not to know about the

FBIs Carnivore system; and 82.5 percent claimed not to

know what the Total Information Awareness program is.

Our sample also showed a lack of knowledge about

technological or legal forms of privacy protection. Even in

INTERNATONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN TECHNOLOGY

95

2014 IJIRT | Volume 1 Issue 5 | ISSN : 2349-6002

our technologically savvy and educated sample, many

respondents could not name or describe an activity or

technology to browse the Internet anonymously to prevent

others from identifying their IP address (over 70 percent),

be warned if a Web sites privacy policy was

incompatible with their privacy preferences (over 75

percent), remain anonymous when completing online

payments (over 80 percent), or protect emails so that only

the intended recipient can read them (over 65 percent).

Fifty-four percent of respondents could not cite or

describe any law that influenced or impacted privacy.

Respondents also had a fuzzy knowledge of general

privacy guidelines. For example, when asked to identify

the OECD Fair Information Principles,22 some

incorrectly stated that they include litigation against

wrongful behavior and remuneration for personal data

(34.2 percent and 14.2 percent, respectively).

Bounded rationality

Even if individuals have access to complete information

about their privacy risks and modes of protection, they

might not be able to process vast amounts of data to

formulate a rational privacy-sensitive decision. Human

beings rationality is bounded, which limits our ability to

acquire and then apply information.13 First, even

individuals who claim to be very concerned about their

privacy do not necessarily take steps to become informed

about privacy risks when information is available. For

example, we observed discrepancies when comparing

whether subjects were informed about the policy

regarding monitoring activities of employees and students

in their organization with their reported level of privacy

concern. Only 46 percent of those individuals with high

privacy concerns claimed to have informed themselves

about the existence and content of an organizational

monitoring policy. Similarly, from the group of

respondents with high privacy concerns, 41 percent admit

that they rarely read privacy policies.

EXPERIMENTAL RESULTS

The techniques developed in assume that each party has an

internal device that can verify whether they are telling the

truth or not.

V.

CONCLUSION

By juxtaposing their differences, we were able to identify

how the surveillance and social privacy researchers ask

complementary questions. We also made some first attempts

at identifying questions we may want to ask in a world

where the entanglement of the two privacy problems is the

point of departure. We leave as a topic of future research a

more thorough comparative analysis of all three approaches.

We believe that such reflection may help us better address

the privacy problems we experience as OSN users,

regardless of whether we do so as activists or consumers.

REFERENCES

[1] Alessandro Acquisti and Jens Grossklags. Privacy and

rationality in individual decision making. IEEE Security and

Privacy, 3(1):26 33, January/February 2005.

[2] J. Anderson, C. Diaz, J. Bonneau, and F. Stajano.

Privacy-Enabling Social Networking over Untrusted

Networks. In ACM Workshop on Online Social Networks

(WOSN), pages 16. ACM, 2009.

IJIRT 100202

INTERNATONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN TECHNOLOGY

96

2014 IJIRT | Volume 1 Issue 5 | ISSN : 2349-6002

[3] Miriam Aouragh and Anne Alexander. The Egyptian

Experience: Sense and Nonsense of the Internet

Revolutions. International Journal of Communications,

5:1344 1358, 2011.

[4] F. Beato, M. Kohlweiss, and K. Wouters. Scramble!

your social network data. In Privacy Enhancing

TechnologiesSymposium, PETS 2011, volume 6794 of

LNCS, pages 211225. Springer, 2011.

[5] B. Berendt, O. Gunther, and S. Spiekermann. Privacy

in E-Commerce: Stated Preferences vs. Actual Behavior.

Communications of the ACM, 48(4):101106, 2005.

[6] E. De Cristofaro, C. Soriente, G. Tsudik, and A.

Williams. Hummingbird: Privacy at the time of twitter. In

IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, pages 285

299. IEEE Computer Society, 2012.

[7] A. Cutillo, R. Molva, and T. Strufe. Safebook: A

privacy-preserving online social network leveraging on

real-life trust. Communications Magazine, 47(12):94

101, 2009.

[8] R. Dingledine, N. Mathewson, and P. Syverson. Tor:

The secondgeneration onion router. In USENIX Security

Symposium, pages 303 320, 2004.

[9] FTC. Ftc charges deceptive privacy practices in

googles rollout of its buzz social network. Online, 03

2011.

[10] Glenn Greenwald. Hillary clinton and internet

freedom. Salon (Online), 9. December 2011.

[11] James Grimmelmann. Saving facebook. Iowa Law

Review, 94:1137 1206, 2009.

[12] Kevin D. Haggerty and Richard V. Ericson. The

Surveillant Assemblage. British Journal of Sociology,

51(4):605 622, 2000.

[13] Heather Richter Lipford, Jason Watson, Michael

Whitney, Katherine Froiland, and Robert W. Reeder.

Visual vs. Compact: A Comparison of Privacy Policy

Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 28th international

conference on Human factors in computing systems, CHI

10, pages 11111114, New York, NY, USA, 2010.

ACM.

[14] Evgeny Morozov. Facebook and Twitter are just

places revolutionaries go. The Guardian, 11. March 2011.

[15] Deirdre K. Mulligan and Jennifer King. Bridging the

gap between privacy and design. Journal of Constitutional

Law, 14(4):989 1034, 2012.

[16] Leysia Palen and Paul Dourish. Unpacking privacy

for a networked world. In CHI 03, pages 129 136,

2003.

IJIRT 100202

[17] Kate Raynes-Goldie. Privacy in the Age of Facebook:

Discourse, Architecture, Consequences. PhD thesis, Curtin

University, 2012.

[18] Rula Sayaf and Dave Clarke. Access control models for

online social networks. In Social Network Engineering for

Secure Web Data and Services. IGI - Global, (in print)

2012.

[19] Fred Stutzman and Woodrow Hartzog. Boundary

regulation in social media. In CSCW, 2012.

[20] Irma Van Der Ploeg. Keys To Privacy. Translations of

the privacy problem in Information Technologies, pages

1536. Maastricht: Shaker, 2005.

AUTHOR DETAILS:

First Author: Amula Sreelatha received B.Tech in

computer Science and Engineering from Malla Reddy

Institute of Engineering and Technology, Hyderabad, in the

year 2012. She is currently M.Tech student in Computer

Science and Engineering Department from Marri Laxman

Reddy Institute of Technology. And her research interested

areas are in the field of Networking, Information Security

and Cloud Computing, Mobile Computing.

Second Author: B. Madhuravani, Department of CSE,

MLRIT, Dundigal, Hyderabad. Doing PhD in Computer

Science &Engineering, JNTUH. Research interests include

Information Security, Computer Networks, Distributed

Systems and Data Structures. And she is working as Asst.

Professor, Department of Computer science & Engineering,

MLR Institute of Technology , Dundigal Hyderabad,

T.S.,India.

INTERNATONAL JOURNAL OF INNOVATIVE RESEARCH IN TECHNOLOGY

97

You might also like

- Ef Ficient and Secure Chaotic S-Box For Wireless Sensor NetworkDocument14 pagesEf Ficient and Secure Chaotic S-Box For Wireless Sensor NetworkDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Quantum Cloning Attacks Against PUF-based Quantum Authentication SystemsDocument15 pagesQuantum Cloning Attacks Against PUF-based Quantum Authentication SystemsDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Zhao 2015Document14 pagesZhao 2015DrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Zhang2016 PDFDocument15 pagesZhang2016 PDFDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Pair-Wise Key Agreement and Hop-By-Hop Authentication Protocol For MANETDocument9 pagesPair-Wise Key Agreement and Hop-By-Hop Authentication Protocol For MANETDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Parallel Chaotic Hash Function Based On The Shuffle-Exchange NetworkDocument13 pagesParallel Chaotic Hash Function Based On The Shuffle-Exchange NetworkDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Cryptanalysis and Improvement On A Parallel Keyed Hash Function Based On Chaotic Neural NetworkDocument10 pagesCryptanalysis and Improvement On A Parallel Keyed Hash Function Based On Chaotic Neural NetworkDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Zhan2017 PDFDocument14 pagesZhan2017 PDFDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Sensors: A Secure and E Fficient Handover Authentication Protocol For Wireless NetworksDocument16 pagesSensors: A Secure and E Fficient Handover Authentication Protocol For Wireless NetworksbharathNo ratings yet

- Ferng2016 PDFDocument19 pagesFerng2016 PDFDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Efficient Centralized Approach To Prevent From Replication Attack in Wireless Sensor NetworksDocument12 pagesEfficient Centralized Approach To Prevent From Replication Attack in Wireless Sensor NetworksDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- The (In) Adequacy of Applicative Use of Quantum Cryptography in Wireless Sensor NetworksDocument21 pagesThe (In) Adequacy of Applicative Use of Quantum Cryptography in Wireless Sensor NetworksDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- ESF: An Efficient Security Framework For Wireless Sensor NetworkDocument19 pagesESF: An Efficient Security Framework For Wireless Sensor NetworkDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Cryptanalysis and Improvement of A Chaotic Maps-Based Anonymous Authenticated Key Agreement Protocol For Multiserver ArchitectureDocument10 pagesCryptanalysis and Improvement of A Chaotic Maps-Based Anonymous Authenticated Key Agreement Protocol For Multiserver ArchitectureDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Rupesh Nomula, Mayssaa El Rifai and Pramode VermaDocument12 pagesRupesh Nomula, Mayssaa El Rifai and Pramode VermaDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- A Security Enhanced Authentication and Key Distribution Protocol For Wireless NetworksDocument10 pagesA Security Enhanced Authentication and Key Distribution Protocol For Wireless NetworksDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Fine-Grained Data Access Control For Distributed Sensor NetworksDocument15 pagesFine-Grained Data Access Control For Distributed Sensor NetworksDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Towards Secure Quantum Key Distribution Protocol For Wireless Lans: A Hybrid ApproachDocument18 pagesTowards Secure Quantum Key Distribution Protocol For Wireless Lans: A Hybrid ApproachDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Debiao He: A New Handover Authentication Protocol Based On Bilinear Pairing Functions For Wireless NetworksDocument8 pagesDebiao He: A New Handover Authentication Protocol Based On Bilinear Pairing Functions For Wireless NetworksDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Location-Based Data Encryption For Wireless Sensor Network Using Dynamic KeysDocument8 pagesLocation-Based Data Encryption For Wireless Sensor Network Using Dynamic KeysDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Parallel Chaotic Hash Function Construction Based On Cellular Neural NetworkDocument11 pagesParallel Chaotic Hash Function Construction Based On Cellular Neural NetworkDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Lee2015 PDFDocument8 pagesLee2015 PDFDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- A Dynamic Trust Management System For Wireless Sensor NetworksDocument9 pagesA Dynamic Trust Management System For Wireless Sensor NetworksDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Lin2013 PDFDocument19 pagesLin2013 PDFDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Uncorrected Proof: A Secret Key Establishment Protocol For Wireless Networks Using Noisy ChannelsDocument13 pagesUncorrected Proof: A Secret Key Establishment Protocol For Wireless Networks Using Noisy ChannelsDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- A Practical Authentication Protocol With Anonymity For Wireless Access NetworksDocument10 pagesA Practical Authentication Protocol With Anonymity For Wireless Access NetworksDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- RPSDocument22 pagesRPSDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- Design-Pattern Text BookDocument137 pagesDesign-Pattern Text BookyatriNo ratings yet

- FDPDocument16 pagesFDPDrMadhuravani PeddiNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Rule 98Document3 pagesRule 98Kring de VeraNo ratings yet

- Ahmedking 1200Document97 pagesAhmedking 1200Anonymous 5gPyrVCmRoNo ratings yet

- Cold War Assessment Packet PDFDocument25 pagesCold War Assessment Packet PDFalejandroNo ratings yet

- (Empires in Perspective) Gareth Knapman (Editor), Anthony Milner (Editor), Mary Quilty (Editor) - Liberalism and The British Empire in Southeast Asia-Routledge (2018)Document253 pages(Empires in Perspective) Gareth Knapman (Editor), Anthony Milner (Editor), Mary Quilty (Editor) - Liberalism and The British Empire in Southeast Asia-Routledge (2018)jagadAPNo ratings yet

- Counter AffidavitDocument3 pagesCounter AffidavitMarielle RicohermosoNo ratings yet

- 2017 Zimra Annual Report PDFDocument124 pages2017 Zimra Annual Report PDFAnesuishe MasawiNo ratings yet

- I.1 Philosophical Foundations of EducationDocument15 pagesI.1 Philosophical Foundations of Educationgeetkumar18100% (2)

- Ombudsman vs. Estandarte, 521 SCRA 155Document13 pagesOmbudsman vs. Estandarte, 521 SCRA 155almorsNo ratings yet

- Values-Education - Terrorism - FINALDocument29 pagesValues-Education - Terrorism - FINALBebe rhexaNo ratings yet

- NSTP CM Week 6Document10 pagesNSTP CM Week 6dankmemerhuskNo ratings yet

- Water Refilling StationDocument15 pagesWater Refilling StationJuvie Mangana Baguhin Tadlip0% (1)

- CEI Planet Spring 2023Document16 pagesCEI Planet Spring 2023CEINo ratings yet

- The Most Outstanding Propagandist Was Jose RizalDocument5 pagesThe Most Outstanding Propagandist Was Jose RizalAnonymous G7AdqnemziNo ratings yet

- O P Jindal School - Raigarh (C.G) : Question Bank Set 1Document35 pagesO P Jindal School - Raigarh (C.G) : Question Bank Set 1Horror TalesNo ratings yet

- Osmena V OrbosDocument1 pageOsmena V OrbosMichelle DecedaNo ratings yet

- Railway Express Agency, Inc. v. New York, 336 U.S. 106 (1949)Document8 pagesRailway Express Agency, Inc. v. New York, 336 U.S. 106 (1949)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Garcia Vs DrilonDocument2 pagesGarcia Vs DrilonAndrea Rio100% (1)

- IPRA PresentationDocument15 pagesIPRA PresentationMae Niagara100% (1)

- Gender Resistance & Gender Revolution FeminismsDocument17 pagesGender Resistance & Gender Revolution FeminismsNadeem SheikhNo ratings yet

- ENGLEZA - Bureaucracy and MaladministrationDocument3 pagesENGLEZA - Bureaucracy and MaladministrationCristian VoicuNo ratings yet

- Meralco Securities Vs SavellanoDocument2 pagesMeralco Securities Vs SavellanoKara Aglibo100% (1)

- Letter To RFH: Ariel Dorfman & 'Age-Inappropriate' BooksDocument3 pagesLetter To RFH: Ariel Dorfman & 'Age-Inappropriate' BooksncacensorshipNo ratings yet

- Eliud Kitime, Lecture Series On Development StudiesDocument247 pagesEliud Kitime, Lecture Series On Development Studiesel kitime100% (1)

- Test D'entree en Section Internationale Americaine 2018Document3 pagesTest D'entree en Section Internationale Americaine 2018Secondary CompteNo ratings yet

- HCPNDocument27 pagesHCPNJohn Philip TiongcoNo ratings yet

- C. The Effects of Discrimination in Language Use On FacebookDocument2 pagesC. The Effects of Discrimination in Language Use On FacebookDracula VladNo ratings yet

- TUGAS PRAMUKA DARING - 29 OKT 2021 (Responses)Document13 pagesTUGAS PRAMUKA DARING - 29 OKT 2021 (Responses)EditriNo ratings yet

- 2.14.12 Second Chance Act Fact SheetDocument2 pages2.14.12 Second Chance Act Fact SheetUrbanistRuralsNo ratings yet

- Research SufismDocument12 pagesResearch SufismBilal Habash Al MeedaniNo ratings yet

- Sta. Rosa Development Vs CA and Juan Amante DigestDocument1 pageSta. Rosa Development Vs CA and Juan Amante DigestMirzi Olga Breech Silang100% (1)