Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Diploma in Accounting 2010edit

Uploaded by

Severino ValerioOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Diploma in Accounting 2010edit

Uploaded by

Severino ValerioCopyright:

Available Formats

Diploma in Accounting

Diploma in

Accounting

D1071

Oxford Learning 2007

We have made every effort to trace and contact all copyright holders. If notified, Oxford Learning

Will be pleased to rectify any errors or omissions at the earliest opportunity

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

Consultant:

Oxford Learning

Publishing Manager:

Oxford Learning

Edit Coordinator:

K. Laycock

Project Manager:

Oxford Learning

Page Design:

Oxford College Press

Page Layout:

Oxford College Press

Cover Design:

Oxford College Press

Print Coordination:

Oxford Learning

Online Edition:

Oxford Learning

2008 Oxford Learning. All rights reserved.

Any answers to examination questions or hints to their answers were not provided by any

examination board and are the sole responsibility of the authors.

We are also grateful to numerous organisations for their prior permission to produce materials. A

full list can be obtained by contacting Oxford Learning during published business hours.

We have made every effort to trace and contact any and all copyright holders of any materials used

in this publication. At the earliest opportunity, Oxford Learning will be pleased to rectify any and all

omissions.

No part of this document may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system, or transmitted in any

way or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the

prior permission of Oxford Learning.

This publication is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be

lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers prior consent in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being

imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

Oxford Learning is an independent, self-financing organisation. Since establishment, Oxford

Learning has developed quality flexible open and distance learning materials for adults and

continues to invest in the development of innovative learning systems from first levels to degree and

professional training programs.

Oxford Learning works in conjunction with other institutions to bring the student the most

comprehensive learning materials which aide the student in fulfilling their aims to successfully

complete course mediation whether it be through an end of course examination, course work or

certification through board mediation.

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

Diploma in

Accounting

Unit 1: Introduction of Financial

Accounting

Module 1: Purposes of Accounting and Records

Module 2: Verification of Records Accounts and

Balance Sheets

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

Diploma in

Accounting

Unit 1: Introduction of Financial

Accounting

Module 1: Purposes of Accounting and Records

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

INTRODUCTION TO FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING

INTRODUCTION

Your learning will be built up from the basis of this module, as you will study the principles

of double entry bookkeeping, how to make the proper entries in the accounts and record the

transactions. You will also develop skills in correction of errors and how they affect the Profit

and Loss account and the Balance Sheet. By the end of the lesson you should be able to

prepare Final Accounts for a business.

Do not worry about the terminology used in the module as it will be explained and by the end

of the module you will become familiar with it. A glossary of accounting terms has been

included at the start of the module so that you can refer to it every time you need to.

This module is an introduction to what it is going to be the foundations of your knowledge

and skills throughout this course. It is very important that you understand how the principles

work and how to apply them in practice correctly. Make sure you cover the different topics of

the module and do the questions proposed, as accounting requires a lot of practice too.

At first you may find the module a little bit difficult, but if you work through the examples

and complete the exercises it will become easier. You will find step by step explanations of

how to record transactions, balance the accounts, correct errors, etc.

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

Learning objectives:

Understanding why it is important to keep records

Listing the main users of accounting information and what they are interested in

Listing the books of original entry and explaining the principle of double-entry

bookkeeping

Recording transactions from prime documents

Entering a series of transactions into T-accounts

How the double entry system follows the rules of the accounting equation

How to reconcile the business bank account with the bank statement

Balancing the accounts

How to draw up a trial balance

Preparing Financial Statements: Profit and Loss Account and Balance Sheet

Making adjustments to the accounts at the year end.

How to correct errors in the accounts

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

LESSON 1. PURPOSES OF ACCOUNTING

1.1 . Introduction.

Accounting affects people in their personal lives just as much as it affects very large

organisations. We all use accounting ideas when we plan what we are going to do with our

money. We can do that by writing down a plan (budget) or by simply keeping it in our heads.

However, businesses have too much financial data and it would be very difficult for an owner

or a manager to keep all the details in their heads. Therefore, they need to keep records,

accounting records.

Failing to keep proper records means that there is no way of checking the financial position

of the business. In some cases it may lead to a penalty charged by HM Revenue & Customs

or to a prosecution under the Insolvency Act. A Limited Company is bound by law to keep

financial accounts in accordance with the Companies Act.

1.2 . Why we need to keep records.

The business must at all times know what its financial position is and this will be evident

when records can be produced showing the amount owing to the business and the amount of

money it owes to other people. Records of payments made and received are very important.

These enable us to ensure these payments are made on time and to know when a customer

paid us.

The reasons for keeping records are numerous:

To provide a permanent record of financial transactions.

To provide information from which financial statements can be prepared.

To provide information from which management report can be prepared.

To provide a means of controlling assets.

To provide information for decision making.

To comply with statutory regulations.

These accounting records will contain details of all cash received and paid, goods bought and

sold, assets bought to be used not sold, and so on.

To be useful to the business, when accounting data is being recorded, it has to be classified

and then summarised. It can then be discovered how much profit or loss is being made, what

is owned by the business, and what is owed by it.

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

It is this information that is available in part or in whole to the range of users.

1.3 . Who is interested in the accounting records?

Apart from the management of an organisation, there are other groups, each of which may

believe it has a reasonable right to obtain information about an organisation. These groups

include the owners, shareholders, employees, lenders, suppliers, customers, competitors,

government and its branches, and the public interest. Those in the wider interest groups are

sometimes referred to as stakeholders.

Owners

They want to be able to see whether or not the business is profitable. They also want to know

what the financial resources of the business are. They need the information as quickly as

possible, as it is their responsibility to employ the resources of the business in an efficient

way and to meet the objectives of the business. The information needed to carry out this

responsibility ought to be of high quality and in an understandable form so far as the owners

are concerned.

Where the ownership is separate from the management of the business, as it is the case with a

limited liability company, the owners are more appropriately viewed as investors who entrust

their money to the company and expect something in return, usually a dividend and a growth

in the value of their investment as the company prospers. As providing money to fund a

business is a risky act, they need information to help them decide whether they should buy,

hold or sell, so that they can have a return on their investment. They are also interested in

information on the entitys financial performance and financial position that helps them to

assess its cash-generation abilities.

Shareholders

Year end accounts have to be supplied to all shareholders and investors. These accounts will

confirm whether or not the business is a good investment. Shareholders are interested in

evaluating the performance of the entity; assessing the effectiveness of the entity in achieving

objectives and its liquidity, its present or future requirements for additional working capital,

and its ability to raise long-term and short-term finance; estimating the future prospects of the

entity, including its capacity to pay dividends, and predicting future levels of investment.

Employees

They are interested in information about the stability and profitability of their employers.

They are also interested in information that helps them to assess the ability of the entity to

provide remuneration, retirement benefits and employment opportunities.

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

The matters which are likely to be of interest to employees include: the ability of the

employer to meet wage agreements; managements intention regarding employment levels,

locations and working conditions; job security; pay rise.

Lenders

Lenders are interested in information that enables them to determine whether their loans, and

the related interest, will be paid when due.

Loan creditors provide finance on a longer-term basis; therefore, they wish to assess the

economic stability and vulnerability of the borrower. They are particularly concerned with

the risk of default and its consequences. They may impose conditions which require the

business to keep its overall borrowing within acceptable limits. Banks will ask for cash flow

projections showing how the business plans to repay, with interest, the money borrowed.

Suppliers

Suppliers of goods and services (trade creditors) are interested in information that enables

them to decide whether to sell to the entity and to determine whether amounts owing to them

will be paid when due.

Trade creditors have very little protection if the entity fails because there are insufficient

assets to meet all liabilities. So they have to exercise caution in finding out whether the

business is able to pay and how much risk of non-payment exists. They may obtain the

information from the local press and trade journals and the Chamber of Trade, apart from the

financial statements, which may confirm the information obtained from other sources.

Customers

Customers have an interest in information about the continuance of an entity, especially when

they have a long-term involvement with, or are dependent upon, its prosperity. They need

information concerning the current and future supply of goods and services offered, price and

other product details, and conditions of sale. Much of the information may be obtained from

sales literature or form sales staff of the enterprise, or form trade and consumer journals.

The financial statements provide useful confirmation of the reliability of the enterprise itself

as continuing source of supply. They also confirm the capacity of the entity in terms of fixed

assets and working capital and give some indication of the strength of the entity to meet any

obligations under guarantees or warranties.

Competitors

They want as much pertinent information as they can get. In particular, they will want access

to the internal financial information concerning costs. They are interested in the financial

performance of the enterprise, its cash flow strength to carry out further investment or

expansion, its price structure and margins in order to assess its competitiveness and share

market, and its products.

Oxford Learning 2007

Diploma in Accounting

Government

Government and their agencies are interested in the allocation of resources and, therefore, in

the activities of the entities. They also require information in order to regulate the activities of

entities, assess taxation and provide a basis for national income.

Acting on behalf of the UK governments Treasury Department, HM Revenue and Customs

collects taxes from businesses based on profit calculated according to commercial accounting

practices. They want to know how much tax a business should be paying, whether it is

complying with the VAT regulations, etc.

The public

They have different interests from the other stakeholders groups. They want assurance about

the behaviour and practices of the business.

All these different people may need access to the accounts of a business:

LESSON 2. ACCOUNTING RECORDS

2.1.Primary Accounting Records and the Ledgers.

When a transaction takes place, we need to record as much information as possible

about the transaction. For example, if we sold two printers on credit to ABC Ltd for

100 each, we want to record that we sold two printers for 100 each to ABC Ltd on

credit. We will need to record the address and contact details of the company and the

date of the transaction.

Oxford Learning 2007

10

Diploma in Accounting

A) The Books of prime, or original, entry are the books in which we first record

transactions, such as the sale of the two printers. There is a separate book for each

kind of transaction. These books are known as journals or day books.

The commonly used books of original entry are:

Sales Day Book. Records all credit terms invoices sent out from the business.

Purchase Day Book. Records all credit items invoices received by the

business.

Returns Inwards Day Book. Record all Credit Notes received (Purchases

Returns).

Returns Outwards Day Book. Record all Credit Notes given (Sales Returns).

Cash Book. This records incoming and outgoing payments of bank and cash.

General Journal. It is used for other items. It will be explained in more detail

later on in this lesson.

Entries are made in the books of original entry. The entries are then summarized and

the summary information is entered, using double entry, to accounts kept in the

various ledgers of the business.

When we enter transactions in these books we record:

The date of the transaction

The details relating to the sale or purchase

The folio entry for cross-reference back to the original source document

(invoice, credit note)

The amount of the transaction

The Sales Day Book is simply a list of transactions, the total of which, at the

end of the day, week or month, is transferred to sales account. Bear in mind

that the Day Book is not part of double-entry bookkeeping, but it is used as a

primary accounting record to give a total which is then entered into the

accounts. The most common used of a Sales Day Book is to record credit sales

from invoices issued.

Lets see an example:

On 1 June 2008 you sold goods for 100 on credit to E. Jones, invoice No 101

On 8 June 2008 you sold goods for 150 on credit to M. White, invoice No

102

On 15 June 2008 you sold goods for 250 on credit to T. Young, invoice No

103

Your Sales Day Book will be written up like this:

Sales Day Book

Date

Oxford Learning 2007

Details

Invoice

Folio

Amount

11

Diploma in Accounting

01/06/2008

08/06/2008

15/06/2008

30/06/2008

E. Jones

M. White

T. Young

Total for the month

101

102

103

SL10

SL20

SL22

100.00

150.00

250.00

500.00

The total net credit sales for the month of 500 will be transferred to sales

account in the general ledger.

The Sales Day Book incorporates a folio column which cross-references each

transaction to the personal account of each debtor, where each credit sales

transactions is recorded forming part of the Sales Ledger.

The Purchases Day Book lists the transactions for credit purchases from

invoices received and, at the end of the day, week or month, the total is

transferred to purchases account.

Lets see an example:

On 3 June 2008 you bought goods for 80 on credit from P. Doyle, invoice No

2345

On 10 June 2008 you bought goods for 100 on credit from T. Rice, invoice

No 456

On 18 June 2008 you bought goods for 200 on credit from T. Rice, invoice

No 486

Your Purchases Day Book will be written up like this:

Date

03/06/2008

10/06/2008

18/06/2008

30/06/2008

Purchases Day Book

Details

Invoice

P. Doyle

2345

T. Rice

456

T. Rice

486

Total for the month

Folio

PL10

PL20

PL20

Amount

80.00

100.00

200.00

380.00

The total net credit purchases for the month of 380 will be transferred to

purchases account in the general ledger.

As in the Sales Day Book, the folio column gives a cross-reference to the

creditors accounts and provides an audit trail. The credit purchases

transactions are recorded in the personal accounts of creditors in the Purchase

Ledger.

Returns Day Books:

Oxford Learning 2007

12

Diploma in Accounting

The Sales Returns Day Book is for goods previously sold on credit and now

being returned to the business by its customers.

The Purchases Returns Day Book is for goods purchased on credit by the

business, and now being returned to the suppliers.

The Returns Day Books are primary accounting records and do not form part

of the double-entry bookkeeping system. The transactions are recorded from

prime documents (credit notes issued for sales returns, and credit notes

received for purchases returns). Then the information form the Day Book must

be transferred to the appropriate account in the ledger.

From the previous examples of Sales Day Book and Purchases Day Book, we

now have the following information:

On 20 June 2008 M. White returned goods for 50, credit note No CN1001

issued

On 25 June 2008 we returned goods for 100 to T. Rice, credit note No 123

received

The Sales and Purchases Returns Day Book will be written up like this:

Sales Returns Day Book

Credit Note

CN1001

Date

20/06/2008

Details

M. White

30/06/2008

Total for the month

Purchases Returns Day Book

Invoice

CN123

Date

25/06/2008

Details

T. Rice

30/06/2008

Total for the month

Folio

SL20

Amount

50.00

50.00

Folio

PL20

Amount

100.00

100.00

The total net sales returns and net purchases returns will be transferred to the

sales and purchases returns accounts respectively in the general ledger. And

the amounts of sales returns are credited to the debtors personal accounts in

the sales ledger; in the same way, the purchases returns are debited to the

creditors accounts in the purchases ledger.

Cash books. It records all transactions for bank account and cash account

Oxford Learning 2007

13

Diploma in Accounting

Petty Cash Book. It records low-value cash payments, e.g. expenses, that are

too small to be entered in the main cash book or because there is a box in the

office with a small amount of cash for those expenses: fuel, cleaning, etc.

You are not required to prepare a Petty Cash Book in the examination.

B) The different types of Ledgers are:

Sales Ledger. It contains details of sales made to customers on credit terms. It

records:

Sales made on credit to customers of the business

Sales returns by customers

Payment received from debtors

Cash discount allowed for prompt settlement

The sales ledger does not record cash sales. It contains an account for each

debtor and records the transaction for that debtor.

Purchase Ledger. This is for details of all items which are bought on credit

terms. It contains the accounts of creditors, and records:

Purchases made on credit from suppliers of the business

Purchases returns made by the business

Payments made to creditors

Cash discount received for prompt settlement

The purchase ledger does not record cash purchases. It contains an account for

each creditor and records the transactions with that creditor.

Cash books. It records all transactions for bank account and cash account

The cash book performs two functions within the accounting system:

1. It is a primary accounting record for cash/bank transactions

2. It forms part of the double-entry bookkeeping system.

CASH BOOK

Debit

Cash and bank receipts. From prime

documents:

Receipts issued

Bank paying-in slips

Bank giro credits received

BACS payment received

Credit card vouchers received

Oxford Learning 2007

Credit

Cash and bank payments. From prime

documents:

Cheque book counterfoils

Standing order and direct debits

Debit advice from the bank: bank

charges, interest.

14

Diploma in Accounting

General Ledger. This contains the remaining double entry accounts, nominal

accounts, such as those relating to expenses, fixed assets, and capital. It

contains the accounts to record the double entry for all the items for which the

first entry has been made in any of the above Ledger sections:

Nominal Accounts:

-

Sales account (cash and credit sales), sales returns

Purchases account (cash and credit purchases), purchases returns

Expenses and income, loans, capital, drawings

Value Added Tax (where the business is VAT registered)

Profit and loss

Fixed assets: machinery, vehicles, office equipment

Stock

You will not be required to understand the VAT system or make accounting

records of VAT.

2.2.Documents used in business transactions.

Business documents are important because they are the prime source for the recording

of

business transactions.

We have learnt earlier the different books used to record the transactions which take

place in a business: the books of prime entry. However, we do not know how to

obtain the information for those transactions.

Now you are going to study the different documents which take part in any credit

transaction and in which book that information is recorded. A credit transaction is

where goods are purchased, sold and returned without a payment being made or

received at that particular time.

When an order placed by the buyer, using a purchase order, is received by the seller, it

will be processed; at the time of supplying the goods or services a delivery note is

received by the buyer, which will contain details of the goods or services delivered,

the price charged and the quantity. The seller will request payment by issuing an

invoice, which will contain the details of the buyer, date, the goods supplied, the

quantity and total amount due and the credit terms.

A purchase order is prepared by the buyer, and is sent to the seller. The details

included in a purchase order are: number of purchase order, for tracking; name and

address of buyer; name and address of seller; full description of the goods, reference

numbers, quantity required and unit price; date issue and signature of person

authorised to issue the order.

Oxford Learning 2007

15

Diploma in Accounting

When the goods are despatched to the buyer, a delivery note is prepared. This

delivery note accompanies the goods and gives details of what is being delivered.

When the goods are received by the buyer, a check will need to be made:

To make sure that the goods have been received

To be certain that the goods received are those that were ordered

To ensure that the correct price has been charged

To confirm that the goods are not damaged

To ensure that the proper discount has been given if appropriate

An invoice is issued to advise the customer of goods or services supplied. It is

prepared by the seller and is sent to the buyer. The invoice contains details of the

goods supplied, and states the amount to be paid by the buyer. The information

included in an invoice is: invoice number, name and address of seller, name and

address of buyer, date of sale, delivery address (if different from the invoice address),

date that goods were supplied, quantity supplied and unit price, total amount due,

details of trade discount (if any) and the credit terms.

The information is taken forma copy of the invoice and used to write up the Sales Day

Book. This starts the credit sales bookkeeping procedure.

We have mentioned credit terms and trade discount. Lets explain what they mean:

Credit terms are stated on an invoice to indicate the date by which the invoice

amount is to be paid, e.g. net 30 days means that the amount is payable

within 30 days of the invoice date.

Trade discount is a reduction on the list price of goods. It is the amount

allowed as a reduction when goods are supplied to other businesses, but not to

the general public. The trade discount is never shown in the accounts, only the

amount after the deduction of trade discount is recorded.

Another type of discount is cash discount, which is a reduction given for

prompt payment, e.g. 5% discount for payment within seven days. The buyer

can choose whether to take up the cash discount by paying promptly, or

whether to take longer to pay without cash discount. When cash discount is

taken it needs to be recorded in the accounts.

Goods are sometimes found to be defective or wrongly priced, or over supplied. If this

is the case then the goods are likely to be returned to the seller, who will then issue a

credit note which tells the purchaser that his account is being credited with the cost

of the goods.

A statement of account will be sent out to each debtor at the end of each month. This

statement is prepared by the seller and gives a summary of the transactions that have

taken place and are still owed or outstanding. The details on a statement are: name

and address of seller, name and address of the debtor (who is the buyer), the date of

the statement, details of the transactions along with their reference number and the

amount, and the balance currently due.

Oxford Learning 2007

16

Diploma in Accounting

From all the documents aforementioned the invoice and credit note are the ones used

to record the transactions in the Sales or Purchases Day Book, which will be the

starting point from where the total amounts will be transferred to the appropriate

Ledger: the Sales Ledger or the Purchases Ledger. In the next section you will learnt

the double entry principle and how to do entries into the Accounts.

Payments

Once we have recorded the invoices and credit notes issued and received the next step

is to request and make payment for balance shown on the accounts for each customer

and supplier when the payment becomes due.

The most common method of payment is the cheque.

Cheques are written orders from account holders instructing their banks to pay

specified sums of money to named beneficiaries. They are not legal tender but are

legal documents and their use is governed by the Bills of Exchange Act 1882, and the

Cheques Acts of 1957 and 1992.

If a cheque has counterfoil attached, it can be filled in at the same time as the cheque,

showing the information what was entered on the cheque. The counterfoil is then kept

as a note of what was paid, to whom, and when. Cheques as usually supplied in

books.

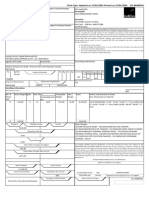

If you look at the cheque above, the drawer is Mr Mamom, and the payee will be the

person or company who the cheque is made payable to: you will write their names on

the Pay line, and below that the amount in words. The use of the double crossed

lines along with the words A/c Payee only means the cheques should be paid only

into the account of the payee named. It is impossible for this cheque to be paid into

any bank account other than that of the named payee.

If the crossing does not contain any of these three terms, A/c Payee only, a cheque

received by someone can be endorsed over to someone else. The person then

Oxford Learning 2007

17

Diploma in Accounting

receiving the cheque could bank it. For example, John Smith receives a cheque from

Tom Rice, he can endorse the cheque and hand it to Anthony Jones as payment of

money by Smith to Jones. Jones can then pay it into his bank account. Smith would

write the words Pay A Jones or order on the reverse side of the cheque and then sign

underneath it, and that is how you endorse a cheque.

Bankers' drafts are cheques drawn directly on the account of a bank rather than the

account of a customer. The comfort they provide is that it is highly unlikely they

would be returned unpaid due to lack of fund

When we want to pay money into a current account, either cash or cheques, or both,

we use a pay-in slip. The counterfoil of the pay-in slip is stamped and initialled by

the banks cashier and returned to the customers a receipt. The pay-in slips used by a

business are usually in a book, with the counterfoil remaining in the book as a

permanent record.

Pay-in slips and cheque books will be furnished by the bank to the customer in order

to action movements on a bank current account. Other transactions documents

include: Standing Order and Direct Debit.

There are two main types of bank accounts:

Current Account which is used for regular payments into and out of a bank

account. They earn little or no interest.

Deposit Account is intended for funds that will not be accessed on a frequent

or regular basis. They earn more interest than current accounts.

Standing Orders are an instruction by an account holder to their bank, to pay regular

amounts of money at stated dates to defined persons or firms.

Direct Debits are an authorisation by the account holder to the creditor to obtain the

money direct from the account holders bank.

BACS (an acronym for Bankers' Automated Clearing Services) is a United

Kingdom scheme for the electronic processing of financial transactions. Direct Debits

and BACS Direct Credits are made using the BACS system. BACS payments take

three working days to clear: they are entered into the system on the first day,

processed on the second day, and cleared on the third day.

The cash receipts and the till rolls contain the information of all the cash sales made

by the business on a daily, weekly or monthly basis. That information will be used to

make entries in the Cash Book Account and the Sales Account.

A bank statement is a document issued by a bank to its customers, listing details of

debit and credit transactions over a given period with a resultant balance of the

account. These statements are issued to cover a range of accounts including current

accounts, loan accounts and deposit accounts.

Oxford Learning 2007

18

Diploma in Accounting

In the bank statement you will find information on bank charges, interest paid and

interest received. Those transactions will need to be recorded in the Cash Book

Account and the appropriate ledger.

As you can see there are a number of documents from where to extract the

information that will be used in the business to record the transactions in business

Accounts.

2.3. Initial entries. Double entry system.

The double entry system was first written down by a mathematician called Luca

Pacioli. His book was published in Venice in 1494 and was called the Summa de

Arithmetica, Geometria, Proportioni et Proportionalitia. Although the double entry

accounting has been in use for years before Pacioli wrote about it, his book is thought

to be the first printed explanation of the double entry system.

What is double entry?

It is a method of cross-checking accounting transactions. It is also a method of

describing accounting processes.

All transactions are entered into Ledger Accounts. The Account is divided into two

identical sections:

Left Hand this is name the Debit (DR) side

Right Hand this is named the Credit (CR) side.

The double entry principle states that every transaction must be entered in the books

twice: on the DEBIT side of one account and on the CREDIT side of another account.

For example, when you buy something you write down the value of the goods you

receive and your write down the value of the cheque that you give to the supplier. The

two values should be same. So, you are entering the amount twice = double entry.

For each transaction it is essential to identify which part is entered on the Debit side

and which part is entered on the Credit side of the two ledger accounts involved. To

work this out we must follow the IN and OUT rule.

The IN part of the transaction is entered on the DEBIT side of an account.

The OUT part of the transaction is entered on the CREDIT side of another account.

Lets see this rule with an example. Example 1:

John Smith started a business on January 1st and his transactions for the first month

are as follows:

Oxford Learning 2007

19

Diploma in Accounting

January 1st. He started with Capital of 5,000 paid into his business bank account

2nd. He buys a van for 3,000 paid by cheque

3rd. He purchased stock for resale for 750 by cheque

7th. He sold goods for 250 the money is paid into the bank

10th. He sells more goods for 750 and the money is paid into the bank

11th. He pays 200 rent by cheque

We draw up a table showing for each transaction the account titles to be used for the

Debit and Credit parts and the reason why are IN and OUT.

DEBIT IN

CREDIT OUT

Jan

1

Account Title

Bank

Reason

Money received

Account Title

Capital

Vehicle

Assets received

Bank

Purchases

Stock received

Bank

Bank

Money received

Sales

10

Bank

Money received

Sales

11

Rent

Value received

from use of

premises

Bank

Reason

Money

from owner

Cheque

paid

Cheque

paid

Stock

delivered

Stock

delivered

Cheque

paid

If you enter the amount for each transaction at each side of the table and you add them

up at the bottom you will see that they balance. The reason for this is based on the

accounting equation, and it is usually shown as:

Capital = Assets Liabilities

Capital represents what the owners have invested in the business. It must equal what

the business owns (its assets) minus what it owes (its liabilities).

The rules for debits and credits are:

Debit entry (Dr) the account which gains value, or records an asset, or an

expense

Credit entry (Cr) the account which gives value, or records a liability, or an

income item

Oxford Learning 2007

20

Diploma in Accounting

Dr

First Account

Cr

Second Account

Cr

Account which gains value

or records an asset, or an

expense

Dr

Account which gives value

or records an liability, or

income/revenue

When one entry has been identified as a debit or credit, the other entry will be on the opposite

side of the other account.

You can see from the picture above how the shape resembles a T; that is why they are

commonly referred to as T-accounts.

For example, if you paid 10 by cheque for a book, you will enter 10 on the left hand (i.e.

debit, DR) side of the book account and on the right-hand (i.e. credit, CR) side of the bank

account:

Dr

Book account

Bank

Cr

10

Dr

Bank account

Book

Cr

10

The description used is to be able to cross reference the two accounts affected. If you look at

your book account you will be able to see that you paid for your book by drawing a cheque

from your bank account. Likewise, if you look at the bank account, you can see that you took

money out of your bank account to buy a book.

At this point you need to understand that transactions increase or decrease assets, liabilities

and capital. Therefore,

To increase an asset we make a DEBIT entry

To decrease an asset we make a CREDIT entry

Oxford Learning 2007

21

Diploma in Accounting

To increase a liability or capital account we make a CREDIT entry

To decrease a liability or capital account we make a DEBIT entry

Accounts

Assets

Liabilities

Capital

To record

An increase

A decrease

An increase

A decrease

An increase

A decrease

Entry in the account

Debit

Credit

Credit

Debit

Credit

Debit

CASH BOOK

Debit

Cash and bank receipts. From prime

documents:

Receipts issued

Bank paying-in slips

Bank giro credits received

BACS payment received

Credit card vouchers received

Credit

Cash and bank payments. From prime

documents:

Cheque book counterfoils

Standing order and direct debits

Debit advice from the bank: bank

charges, interest.

DOUBLE ENTRY BOOKKEEPING

Credit

Sales Ledger or

Debtors account

(money received)

Debit:

General Ledger

nominal account

(interest received)

Purchases Ledger or General Ledger

creditors account

nominal account

(amounts paid)

(rent account)

Example 2. Anthony Brown started a business on January 1st, and he has the following

transactions in the month:

edit:

Started with capital of 2,000 paid into the business bank account

Paid a cheque for 500 for the rent of the shop

Bought equipment for 600, paid by cheque

Purchased stock for resale and paid 450 by cheque

Returned some equipment unused. A cheque for 200 was received and paid into the

bank

7. Sold goods for 75; the money was paid into the bank

9. Bought business stationery for 12 and paid by cheque

17. Received a loan of 500 from A Finance; the cheque was banked

24. Sold more stock for 320 and the money was paid into the bank

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Oxford Learning 2007

22

Diploma in Accounting

27. Paid wages of 35 by cheque

27. The telephone bill of 18 was paid by cheque

30. Drew a cheque for personal use for 300

You are required:

a) To draw up a table showing (for each transaction) the account titles to be used for the

Debit and Credit parts and the reasons why they are IN or OUT.

b) To write up a set of ledger accounts, which you must balance.

a) DEBIT IN

Jan

Account Title

1

Bank

owner

2

Rent

CREDIT OUT

Reason

Account Title Reason

Money received

Capital

Money from

Bank

Cheque paid

Bank

Bank

Equipment

Sales

Bank

Loan from

A Finance

Sales

Bank

Bank

Bank

Cheque paid

Cheque paid

Asset returned

Stock delivered

Cheque paid

Money paid

3

4

5

7

9

17

Equipment

Purchases

Bank

Bank

Stationery

Bank

Value received

From use of premises

Assets received

Stock received

Cheque received

Money received

Goods received

Cheque Received

24

27

28

30

Bank

Wages

Telephone

Drawings

Money received

Value received

Service received

Money received

Stock delivered

Cheque paid

Cheque paid

Cheque paid

(Note: Goods or stock bought for resale are called Purchases, money drawn for personal

use is called drawings)

b) Ledger Accounts

Oxford Learning 2007

23

Diploma in Accounting

BANK ACCOUNT

Debit

Date

Jan 1

Jan 5

Jan 7

Jan 17

Jan 24

Feb 1

Credit

Detail

Capital

Equipment

Sales

Loan A Finance

Sales

2,000.00

200.00

75.00

500.00

320.00

Balance b/d

3,095.00

1,180.00

Date

Jan 2

Jan 3

Jan 4

Jan 9

Jan 27

Jan 28

Jan 30

Jan 31

Detail

Rent

Equipment

Purchases

Stationery

Wages

Telephone

Drawings

Balance c/d

500.00

600.00

450.00

12.00

35.00

18.00

300.00

1,180.00

3,095.00

CAPITAL

Date

Jan 31

Debit

Detail

Balance c/d

Date

2,000.00 Jan 1

Feb 1

Credit

Detail

Bank

2,000.00

Balance b/d

2,000.00

RENT

Date

Jan 2

Feb 1

Debit

Detail

Bank

Balance c/d

Oxford Learning 2007

Date

500.00 Jan 31

500.00

Credit

Detail

Balance c/d

500.00

24

Diploma in Accounting

EQUIPMENT

Date

Jan 3

Debit

Detail

Bank

Feb 1

Balance b/d

Date

600.00 Jan 5

Jan 31

600.00

Credit

Detail

Bank

Balance c/d

200.00

400.00

600.00

400.00

PURCHASES

Date

Jan 4

Feb 1

Debit

Detail

Bank

Balance b/d

Date

450.00 Jan 30

450.00

Credit

Detail

Balance c/d

450.00

SALES

Date

Jan 31

Debit

Detail

Balance c/d

Date

395.00 Jan 7

Jan 24

395.00

Feb 1

Credit

Detail

Bank

Bank

75.00

320.00

395.00

Balance b/d

395.00

STATIONERY

Date

Jan 9

Feb 1

Debit

Detail

Bank

Balance b/d

Oxford Learning 2007

Date

12.00 Jan 31

12.00

Credit

Detail

Balance c/d

12.00

25

Diploma in Accounting

Date

Jan 31

Debit

Detail

Balance c/d

LOAN - A FINANCE

Credit

Date

Detail

Jan

17

500.00

Bank

Feb 1

Balance b/d

500.00

500.00

WAGES

Date

Jan 27

Feb 1

Debit

Detail

Bank

Balance

Date

35.00 Jan 31

35.00

Credit

Detail

Balance c/d

Credit

Detail

Balance c/d

Credit

Detail

Balance c/d

35.00

TELEPHONE

Date

Jan 28

Feb 1

Debit

Detail

Bank

Balance

Date

18.00 Jan 31

18.00

18.00

DRAWINGS

Date

Jan 30

Feb 1

Debit

Detail

Bank

Balance

Oxford Learning 2007

Date

300.00 Jan 31

300.00

300.00

26

Diploma in Accounting

2.4. Balancing the account

At regular intervals, often at the end of each month, accounts are balanced in order to show

the amounts of purchases, sales, purchases returns, sales returns, fixed assets (premises,

machinery), etc.

How do we balance the accounts?

Balancing the accounts is done in five stages:

1. Add up both sides to find out their totals, but do not write anything in the accounts

yet.

2. Deduct the smaller total from the larger total to find the balance.

3. Now enter the balance on the side with the smallest total. This is the balance to be

carried down (c/d). Do not forget to enter the last day of the period.

4. Enter totals on a level with each other.

5. The balance is then brought down (b/d), on the other side, below the totals. This is

the starting amount for the next period. Do not forget to enter the first day of the next

period.

BANK ACCOUNT

Debit

Date

Jan 1

Jan 5

Jan 7

Jan 17

Jan 24

Credit

Detail

Capital

Equipment

Sales

Loan A Finance

Sales

2,000.00

200.00

75.00

500.00

320.00

Date

Jan 2

Jan 3

Jan 4

Jan 9

Jan 27

Jan 28

Jan 30

Jan 31

3,095.00

Feb 1

Balance b/d

500.00

600.00

450.00

12.00

35.00

18.00

300.00

1,180.00

3,095.00

1,180.00

These are the totals on

a level with each other

Oxford Learning 2007

Detail

Rent

Equipment

Purchases

Stationery

Wages

Telephone

Drawings

Balance c/d

This is the balance

to be carried down

27

Diploma in Accounting

Diploma in

Accounting

Unit 1: Introduction of Financial

Accounting

Module 2: Verification of Records Accounts and

Balance Sheets

Oxford Learning 2007

28

Diploma in Accounting

LESSON 3. VERIFICATION OF ACCOUNTING RECORDS

3.1. The trial balance

You have learnt that under the principle of double entry bookkeeping that for each debit entry

there is a credit entry, and for each credit entry there is a debit entry.

At the end of an accounting period, which is usually 12 months, a trial balance is extracted from

the accounting records in order to check the arithmetical accuracy of the double-entry

bookkeeping, i.e. that the debit entries equal the credit entries.

A trial balance is a list of the balances of every account forming the ledger, distinguishing

between those accounts which have debit balances and those which have credit balances.

The intervals at which a trial balance can be extracted are usually at the end of the month and/or

at the end of the accounting period (usually 12 months).

How to prepare a trial balance?

The Trial Balance is not an account, it is a list of accounts which have a balance.

The first step in preparing a trial balance is to go through the Ledger and balance all the

accounts, including the Cash Book.

The balance is always brought down, and the side on which it is brought down is the side it is

entered into the Trial Balance.

Oxford Learning 2007

29

Diploma in Accounting

Example:

B&N Ltd

Trial Balance as at 31 December 2007

Stock at 31 Dec

Capital

Bank

Purchases

Cash

Wages

Sales

Fixtures and Fittings

Motor vehicles

Office Equipment

Insurance

Advertising

Debtors

Creditors

Dr

4,000.00

Cr

8,680.00

825.00

7,280.00

150.00

950.00

9,670.00

1,050.00

2,000.00

435.00

275.00

350.00

2,035.00

1,000.00

19,350.00

19,350.00

Usually, Debit balances are Assets or Expenses; Credit balances are Liabilities (including

Capital) or Incomes.

If the total debits agree with the total credits then the Trial Balance is balanced. This does not

necessarily means that no errors have been made, because there are certain types of errors which

do not show up in the Trial Balance. These will be explained later.

When the Trial Balance does not balance it indicates that one or more entries are missing or

incorrect.

Always total each side of the Trial Balance and calculate the difference. That could be the

amount has been omitted.

The error could be an incorrect addition or a transposition, where you intend to write for

instance 145 but instead you enter 154.

Alternatively it may help to halve the difference and then see if it has been put in the

wrong side.

If the amount is exactly divisible by 9, this could be as a result of transposition.

Oxford Learning 2007

30

Diploma in Accounting

Check that the balance of each account has been correctly entered in the trial balance, and

under the correct heading, i.e. debit or credit.

Check the calculation of the balance of each account.

If the error is still not found, it is necessary to check the bookkeeping transactions since

the date of the last trial balance, by going back to the original documents and primary

accounting records.

Practice: Now go back to Example 2 in section 2.3 above and extract the Trial Balance.

3.2. The general journal

The Journal is the last of the Books of Original Entry. Any entries which do not go through the

day books, cash books or petty cash book should be entered in the Journal.

The Journal is the book of Prime, or Original, Entry for items for which there is no Day Book,

for example:

Opening entries

Purchase and sale of fixed assets on credit (e.g. cars, plant and machinery, office

equipment)

Introduction o f assets to the business by the owner

Entries for period-end and year-end adjustments

Transfer of year end balances following preparation of Final Accounts

Corrections of errors

The Journal provides a written record of the details of a transaction and enables an explanation to

be recorded. It is a primary accounting record; it is not part of the double-entry bookkeeping

system. The journal is used to list the transactions that are then to be put through the accounts.

What are the reasons for using a journal?

The reasons are:

To provide a primary accounting record for non-regular transactions

To eliminate the need for remembering why non-regular transactions were put through

the accounts the journal acts as a notebook

To reduce the risk of fraud, by making it difficult for unauthorised transaction to be

entered in the accounting system

To reduce the risk of errors, by listing the transactions that are to be put into the doubleentry accounts

To ensure that entries can be traced back to a prime document, thus providing an audit

trail for non-regular transactions

Oxford Learning 2007

31

Diploma in Accounting

Look at the layout of the journal:

Journal

Date

Details

01-Jan-08 Bank

Capital

Opening capital introduced

Folio Dr

Cr

CB

10,000.00

GL

10,000.00

Remember:

All items must be dated.

The account to be debited is always entered before the account to be credited.

The account to be credited should be written a little to the right under the name of the

account to be debited.

Each entry must have a supporting narrative, with reference to whatever document

supports the entry, such as invoice number or management instructions

The folio column cross-references to the division of the ledger where each account will

be found

A journal entry always balances, i.e. debit and credit entries are for the same amount or

total.

The Journal is not a double entry account. Once the journal entry is made, the entry in the

double entry accounts can then be made.

Oxford Learning 2007

32

Diploma in Accounting

Examples of journal entries:

Journal J1

Date

Sept 3

Sept 4

Sept 5

Sept 6

Details

Motor vehicle account

Carlan Ltd

Purchase of Fleet car

Invoice No 0246

C. Chapman

Equipment Account

Sale of computer cover

Invoice No 123

Machinery account

Machine Tool Co.

Buy printer

Invoice No MTC/47

Bank

Capital

Folio

GL4

PL7

Dr

Cr

14,500.00

14,500.00

SL8

GL5

135.00

GL3

PL8

6,800.00

CB1

GL10

135.00

800.00

800.00

Owner introduces 800 into

business

After the journal entry has been made, the transaction can be recorded in the double-entry

accounts:

Date

Sept 6

Date

Sept 3

BANK ACCOUNT CB1

Date

Details

800.00

Details

Capital

Folio

J1

Details

Carland Ltd

MOTOR VEHICLE ACCOUNT GL4

Folio

Date

Details

J1

14,500.00

Oxford Learning 2007

Folio

Folio

33

Diploma in Accounting

Details

Machine Tool Co

MACHINERY ACCOUNT GL3

Folio

Date

Details

J1

6,800.00

Folio

Date

Sept 4

Details

Computer Cover

Folio

J1

C. CHAPMAN SL8

Date

Details

135.00

Folio

Date

Details

Folio

Date

Sept 5

Date

Date

CAPITAL ACCOUNT G10

Date

Details

Sept 6 Bank

CARLAND LTD G10

Date

Details

Sept 3 Fleet Car

Details

Folio

Details

EQUIPMENT ACCOUNT GL5

Folio

Date

Details

Sept 4 C. Chapman

Oxford Learning 2007

Folio

J1

800.00

Folio

J1

14,500.00

Folio

J1

135.00

34

Diploma in Accounting

Date

Details

MACHINE TOOL COMPANY PL8

Folio

Date

Details

Sept 5 Machinery account

Folio

J1

6,800.00

If the trial balance does not balance, i.e. the two totals are different, there is an error or more than

one error: either in the addition of the trial balance and/or in the double-entry bookkeeping.

3.3. Checking the ledger.

As mentioned earlier in this course, a trial balance does not prove the complete accuracy of the

accounting records. There are six types of errors that are not shown by a trial balance:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Error of omission

Reversal of entries

Error of commission

Error of principle

Error of original entry (or transcription)

Compensating error

1. Error of omission. Entry missed out completely

An invoice for a transaction may be omitted completely, as in the case of a purchase

invoice not being entered into the purchases day books. The entry is then not made into

the credit side of the suppliers account, e.g. a transaction is made for 200 but the

invoice is not entered into the system. The day book and nominal ledger totals will be the

same but will be the amount of the invoice short. The trial balance will also balance but

again will be that amount short.

2. Reversal of entries. This happens when the entry is posted to the wrong side of the

account, e.g. P. Long buys goods to the value of 150 but this amount is credited to his

account instead of being debited. The same amount is debited to the sales account. The

double entry is complete but the entries are in reverse. Correcting this type of error

involves doubling the amount once to eliminate the error and again to put in the correct

item.

3. Error or commission. The amount to be posted has been entered into the wrong specific

account but into an account of the same general type, e.g. D. West has been credited with

20 instead of D. J. West. Both of these accounts are personal accounts in the Purchases

ledger and in this case the double entry has been completed.

Oxford Learning 2007

35

Diploma in Accounting

4. Error of principle. The amount posted has not only gone to the wrong account but that

account is a different type of account. An example of this is where, after the purchase of a

motor van for 1,800, the amount has been posted to the Motor Expenses Account

(nominal ledger) instead of the Motor Van account (capital account). Here, capital

expenditure has been treated as revenue.

5. Error of original entry. The wrong figure has been used in both the postings. An example

of this is when an invoice is over or understated when entered into the system, e.g. D.

Smith bought goods for 150 but the amount entered into the sales day book was 105.

The amount of 105 from the sales day book will be posted to the sales account which

will result in both accounts being understated by 45.

6. Compensating error. This is where one error cancels out another of the same value but is

not connected, e.g. the wages account is overstated by 200 and the purchases account is

understated by 200. This will mean that the errors will cancel one another out when the

totals are transferred to the trial balance.

As you can see now, all these errors may occur and yet the Trial Balance will still balance. A

trial balance that balances only confirms that the arithmetic is correct but all the entries may not

be.

3.4. Bank Reconciliation

The bank account kept by the business is unlikely to show the same balance as the bank

statement. Why do you think this is?

Probably you are thinking that there is an error, as it would be the first thing most people would

think. The error may have been made either by the business or by the bank. Nevertheless, that is

not normally the case, although there may be discrepancies in some of the items in the bank

statement and the bank account kept by the business.

Apart from the event of a possible error made, there are other reasons which explain why the

balance is different:

The bank may make entries which the business has not taken into account, e.g. bank

charges or bank interest. Those amounts may not be known until the statement is

received. However, with established business accounts the banks will now often advise

the charges and interest in advance before the transaction date. This gives the customer

the advantage of being able to discuss the charges with the bank and make any savings on

the type of transactions he or she uses.

Payments may be made to the business, or on behalf of the business, by means of

standing orders or direct debits. With standing order. We instruct the bank as to how

Oxford Learning 2007

36

Diploma in Accounting

much is to be paid. With a direct debit we give the third party the right to let the bank

know how much is to be debited.

There may be differences due to the timing of transactions. Cheques are received and

paid into the bank, these are recorded and added to the bank account, by the business. At

this time the bank may not have cleared them. Cheques paid-out will have to be sent to

the creditor, paid-into the creditors bank and then processed; this means a delay of

several days.

There are two things to notice regarding the statement:

1. It uses the running balance format

2. The entries are the opposite to the Cash Book Accounts in the companys books of

account, i.e., the Debit side is for Payments, the Credit side is for Receipts.

This is because, from the banks point of view, the business is a creditor of the bank, unless the

account is overdrawn).

Some abbreviations used on a bank statement are explained at the foot of the page, but I have

listed examples of some of the most common ones;

SO = standing order

DD = direct debit

TR = transfer

OD = balance overdrawn

Stages in the reconciliation

1. When studying the bank account and the bank statement majority of entries will agree:

these you need to tick off, so that you can concentrate on finding the entries which do not

agree.

Remember: you are looking for receipts which you have entered in the debit side of your

cash book bank account and which also appear on the credit side of the bank statement.

Likewise, payments will have been entered on the credit side of your cash book bank

account and on the debit column of the bank statement.

2. When that stage is complete, you may have some items unticked in both the cash book

bank account and the statement.

The items left unticked on the statement will be amounts that have been recorded by the

bank but not the business. The cash book needs to be updated with this information

before the account can finally be balanced off. The account will normally have been left

open so that these adjustments can be made when the statement arrives.

These items may include bank charges or interest, etc.

Oxford Learning 2007

37

Diploma in Accounting

3. We are now left with the items left unticked in the cash book. These differences are

probably due to the time delay. These differences need to be reconciled with the bank

statement. This is done by means of a bank reconciliation statement showing the effective

date of this action.

Lets see how it is done with an example. We will start with the balance of the bank statement

and reconcile it to the Cash Book:

Date

Apr 1

Apr 12

Apr 20

Apr 27

Apr 30

Detail

E. Slater

B. Brockle

B. Young

K. Palm

J. Bow

Apr 30

Balance b/d

Date

Apr 2

Apr 6

Apr 11

Apr 13

Apr 17

Apr 20

Apr 27

Apr 30

CASH BOOK

BANK ACCOUNT

Date

540.00 Apr 2

600.00 Apr 7

926.00 Apr 14

69.00 Apr 26

700.00 Apr 30

Apr 30

2,835.00

1,697.00

Detail

E. Slater

F. Keeble

J. Wessley

s/o W. Tyre

B. Brockle

R. Hull

d/d W. Tebb

B. Young

Tr. K. Robb

K. Palm

Bank Charges

K. Palm. Cheque returned

BANK STATEMENT

Dr

Detail

F. Keeble

J. Wessley

R. Hull

D. Rogers

C. Holme

Balance c/d

Cr

540.00

24.00

252.00

100.00

600.00

74.00

125.00

926.00

50.00

69.00

10.00

69.00

Balance

540.00

516.00

264.00

164.00

764.00

690.00

565.00

1,491.00

1,541.00

1,610.00

1,600.00

1,531.00

24.00

252.00

74.00

418.00

370.00

1,697.00

2,835.00

CR

CR

CR

CR

CR

CR

CR

CR

CR

CR

CR

CR

Required: Prepare a bank reconciliation statement as at 30 April with the information provided.

1. Tick off the common items.

2. Now you should be left with:

Oxford Learning 2007

38

Diploma in Accounting

Bank Account:

J. Bow

D. Rogers

C. Holme

Statement:

s/o W. Tyre

d/d W. Tebb

tr. K. Robb

Bank charges

K. Palm. Returned cheque

3. Update the Bank Account DR balance 1,443, as illustrated below

4. Prepare the Statement of Reconciliation.

Date

Apr 30

Apr 20

Detail

Balance b/d

tr. K Robb

May 1

Balance b/d

Oxford Learning 2007

CASH BOOK

BANK ACCOUNT

Date

Detail

1,697.00 Apr 11 W. Tyre

50.00 Apr 17 W. Webb

Apr 30 Bank charges

Apr 30 K. Palm. Returned cheque

Apr 30 Balance c/d

1,747.00

100.00

125.00

10.00

69.00

1,443.00

1,747.00

1,443.00

39

Diploma in Accounting

BANK RECONCILIATION STATEMENT

AS AT 30TH APRIL

Balance per Bank Statement

ADD outstanding lodgement

30th April J. Bow

Deduct cheques not presented

26th April D. Rogers

29th April C. Holme

1531

700

2231

418

370

Total

788

1443

Balance per Cash Book

1443

A bank reconciliation statement is important because, in its preparation, the transactions in the

bank columns of the cash book are compared with those recorded on the bank statement. In this

way, any errors in the cash book or bank statement will be found and can be corrected (or

advised to the bank, if the bank statement is wrong).

The bank statement is an independent accounting record, therefore it will assist in deterring fraud

by providing a means of verifying the cash book balance.

By writing the cash book up-to-date, the organisation has an amended figure for the bank balance

to be shown in the trial balance.

Unpresented cheques over six months old out-of-date cheques can be identified and written

back in the cash book (any cheque dated more than six months ago will not be paid by the

bank).

It is good practice to prepare a bank reconciliation statement each time a bank statement is

received. The reconciliation statement should be prepared as quickly as possible so that any

queries either with the bank statement or in the firms cash book can be resolved. Many firms

will specify to their accounting staff the timescales for preparing bank reconciliation statements

as a guideline, if the bank statement is received weekly, then the reconciliation statement

should be prepared within five working days.

If the bank account is overdrawn, the reconciliation should be carried out in the same way but

with the balance in the minus, e.g.:

Bank statement balance: 100 OD

In the Bank Reconciliation statement your will enter:

Oxford Learning 2007

40

Diploma in Accounting

-100 or (100)

Balance per Bank Statement

3.5. Control Accounts

As a business grows and the number of Debtors and Creditors increase, a far tighter check must

be kept on the Total Balances and also the accuracy of the double-entry.

Control accounts enable us to do this and to speed up the job of calculating total balances for

both Creditors and Debtors.

Control account, like the Trial Balance and Bank Reconciliation, acts a checking device for the

individual accounts which it controls. Thus, control accounts act as an aid to locating errors: if

the control account and subsidiary accounts agree, then the error is likely to lie elsewhere. In this

way the control account acts as an intermediate checking device proving the arithmetical

accuracy of the ledger section.

The two commonly-used control accounts are:

Sales ledger control account the total of the debtors

Purchases ledger control account the total of the creditors

The layout of a sales ledger control account (or debtors control) is shown below:

Dr

Sales Ledger Control Account

Balance b/d (large amount)

Balance b/d (small amount)

Credit sales

Cash/cheques received from debtors

Returned cheques

Cash discount allowed

Interest charged to debtors

Sales returns

Balances c/d (small amount)

Bad debts written off

Set-off/contra entries

Balance c/d (large amount)

Balances b/d (large amount)

Oxford Learning 2007

Cr

Balances b/d (small amount)

41

Diploma in Accounting

Balance b/d. The usual balance on a debtors account is debit and so this will form the large

balance on the debit side. However, it is possible for some debtors to have a credit balance on

their accounts because they has paid for goods and then returned them, or because they have

overpaid in error.

Credit sales. Only credit sales, and not cash sales, are entered in the control account because it is

this transaction that is recorded in the debtors accounts. The total sales of the business will

comprise both credit and cash sales.

Returned cheques. If a debtors cheque is returned unpaid by the bank, i.e. the cheque has

bounced, then entries have to be made in the bookkeeping system to record this. These entries

are:

Debit debtors account

Credit bank account

As the transaction has been made in a debtors account, then the amount must also be recorded in

the sales ledger control account, on the debit side.

Interest charged to debtors. Sometimes a business will charge a debtor for slow payment of an

account. As a debit transaction has been made in the debtors account, so a debit entry must be

recorded in the control account.

Bad debts written off. The entries are:

Debit bad debts written off account

Credit debtors account

As a credit entry has been made in a debtors account, the transaction must also be recorded as a

credit transaction in the control account.

Set-off/contra entries. These entries occur when the same person or business has an account in

both sales and purchases ledger, i.e. they are both customer and supplier. To save having to write

out a cheque to send to each other, it is possible to set-off one account against the other.

The layout of a purchases ledger control account (or creditors control account) is shown below:

Dr

Purchases Ledger Control Account

Balance b/d (small amount)

Balance b/d (large amount)

Cash/cheques paid to creditors

Credit purchases

Cash discount received

Interest charged by creditors

Purchases returns

Balances c/d (small amount

Set-off/contra entries

Balance c/d (large amount)

_________

________

_________

Balances b/d (small amount)

Oxford Learning 2007

Cr

________

Balances b/d (large amount)

42

Diploma in Accounting

Balances b/d. For purchases ledger, containing the accounts of creditors, the large balance b/d is

always on the credit side. However, if a creditor has been overpaid, there may be a small debit

balance b/d.

Credit purchases. Only credit purchases, and not cash purchases, are entered in the control

account. However, the total purchases of the business will comprise both credit and cash

purchases.

Interest charged by creditors. If creditors charge interest because of slow payment, this must

be recorded on both the creditors account and the control account.

Set-off/contra entries. See the explanation given above under Sales Ledger Control Account.

Control accounts use totals. Those totals come from a number of sources in the accounting

system:

Sales ledger control accounts:

total credit sales (including VAT), from the gross column of the sales day book

total sales returns (including VAT), from the gross column of the sales returns day book

total cash/cheques received from debtors, from the cash book

total discount allowed, from the discount allowed column of the cash book, or from

discount allowed account

bad debts, from the journal, or bad debts written off account

purchases ledger control accounts:

total credit purchases (including VAT), from the gross column of the purchases day

book

total purchases returns (including VAT), from the gross column of the purchases returns

day book

total cash/cheques paid to creditors, from the cash book

total discount received, from the discount received column of the cash book, or from

discount received account.

Whilst many businesses merely use Control Accounts as a checking device there are businesses

which actually integrate Control Accounts into their double entry bookkeeping system. In such

circumstances the individual accounts of debtors and creditors are kept only as memorandum

accounts, and the balances of the sales ledger control account and the purchase ledger control

account are recorded in the trial balance as the figures for debtors and creditors respectively.

Oxford Learning 2007

43

Diploma in Accounting

3.6. Suspense accounts and errors

Whist certain errors will not be disclosed by the Trial Balance (error of omission, commission,

principle, original entry, reversal of entries and compensating errors), there are of course errors

of an arithmetical nature which the Trial Balance is designed to detect. Such errors include:

Entries are posted without completing double entry. There may be debits without

corresponding credits or vice versa.

Different amounts are posted as debit and credit entries.

An account is incorrectly totalled or balanced.

Balances shown on the Trial Balance have been listed incorrectly there may be

omissions, duplications or transpositions.

Where the total columns of the Trial Balance fail to agree an investigation into the reason(s) for

the imbalance will have to be carried out. As a temporary measure we will open a Suspense

Account, and by posting the difference in books amount to it, bring the books into balance.

In addition to using the Suspense Account to deal with errors the Suspense Account may also be

used as a holding account. This usually occurs in cases where the correct posting of a

transaction is uncertain due to lack of information, or where a transaction is of a complicated or

unusual nature. This should only be used as a temporary measure until further information

becomes available, following which the posting can be removed from the Suspense Account and

posted correctly.

If the errors are not found before the financial statements are prepared, the suspense account

balance will be included in the balance sheet. Where the balance is a credit balance, it should be

included on the capital and liabilities side of the balance sheet. When the balance is a debit

balance it should be shown on the assets side of the balance sheet. You will learn about assets

and liabilities and the balance sheet in the final section of this unit.

Remember: when the errors are found they must be corrected, using double entry. Each

correction must first have an entry in the journal describing it, and then be posted to the accounts

concerned.

The Trial Balance on 31 December 2007 had a difference of 168. It was a shortage on the debit

side.

A suspense account is opened, and the difference of 168 is entered on the debit side. On 31 May

2008 the error was found. We had made a payment of 168 to K Lee to close his account. It was

correctly entered in the Cash Book, but was not entered in K Lees account.

Oxford Learning 2007

44

Diploma in Accounting

First of all, the account of K Lee is debited with 168, as it should have been in 2007:

K Lee

May 31

Bank

168

Jan 1

Balance b/d

168

Second, the suspense account is credited with 168 so that the account can be closed:

Jan 1

Suspense Accounts

Difference per trial balance

168 May 31

K Lee

168

And the Journal entry is:

The Journal

Dr