Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Young Women's Political Participation Online

Uploaded by

danynchOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Young Women's Political Participation Online

Uploaded by

danynchCopyright:

Available Formats

Political

Science

http://pnz.sagepub.com/

Invisible feminists? Social media and young women's political participation

Julia Schuster

Political Science 2013 65: 8

DOI: 10.1177/0032318713486474

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://pnz.sagepub.com/content/65/1/8

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

School of History, Philosophy, Political Science and International Relations at the Victoria

University of Wellington

Additional services and information for Political Science can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://pnz.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://pnz.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

>> Version of Record - May 31, 2013

What is This?

Downloaded from pnz.sagepub.com at National School of Political on October 7, 2013

Article

Invisible feminists? Social

media and young womens

political participation

Political Science

65(1) 824

The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permissions:

sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0032318713486474

pnz.sagepub.com

Julia Schuster

Abstract

Considering insights from third-wave literature, this paper examines the impact of young womens

online activism on the visibility of feminist engagement in New Zealand. Drawing on 40 interviews with

women of all ages who are concerned with womens political issues in New Zealand, I identify a

generational divide in the ways these women participated in feminist activities and I argue that online

activism is a key form of participation for many young women. Since online activism is only visible to

those who use it, this form of participation hides many young womens activities from the wider public

and from politically active women of older generations. Many of my older interview participants were

not aware of the political energy young women put into online communities such as blogs and Facebook. Thus they expressed concern that there would not be enough young women to pick up their

work once they retired. However, the young women in my study used new media to connect with and

support each other, to have political discussions and to organize events in the real world. The young

women valued new media for its flexibility, accessibility and ability to reach large groups of people.

Moreover, they appreciated its easy and low-cost use. The paper concludes that political online work

offers many opportunities for feminist participation, but it excludes people not using new media, and

thus contributes to the enhancement of a generational divide among women engaging with feminism.

Keywords

feminist generations, online activism, New Zealand, third-wave feminism, womens movement

Introduction

Young women are often said to only rarely engage with traditional political activities1

and to distance themselves from feminism.2 Such criticism often comes from feminists

1.

2.

Anita Harris, Young Women, Late Modern Politics, and the Participatory Possibilities of

Online Cultures, Journal of Youth Studies, Vol. 11, No. 5 (2008), pp. 481 495.

For a literature review, see Christina Scharff, Repudiating Feminism: Young Women in a

Neoliberal World (Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2012).

Corresponding author:

Julia Schuster, University of Auckland, 10 Symonds Street, Level 9, Auckland, 1010, New Zealand.

Email: jsch136@aucklanduni.ac.nz

Schuster

of previous generations who tend to express concern that young women lack commitment to feminism, do not appreciate the gains of previous generations and will not pick

up their work once they have retired.

However, the international feminist third-wave literature has argued for over a

decade that the face of feminism is not fading but rather changing.3 This article

addresses one specific aspect of such change: it investigates how the relatively new

form of online activism affects the relationship between generations of feminists,

and asks whether the alleged disappearance of young feminists is at least partly due

to this shift from offline to online methods of feminist work. With the case study of

New Zealand, I argue that there are a large number of young women who do actively

participate in feminist work and activism. However, many of them choose online

activism as their main form of political participation and thus put their political

energy into a space that excludes people who are not familiar with this form of

organizing. Consequently, the use of online tools contributes to making young feminists invisible not only to the wider public but also to their political peers of older

generations.

The focus on New Zealand derives from this countrys paradigmatic shift towards

neoliberalism since 1984,4 which shaped the characteristics of social justice movements

by enhancing certain social developments such as individualization.5 Many (dominantly)

Western societies adopted neoliberal governance during the same time period, although

not usually as rapidly as New Zealand. Thus, findings are relevant for womens

movements in other Western countries where the influences of neoliberalism are present

but possibly less perceptible.

Womens use of the internet for political purposes has been researched by various

scholars. Morahan-Martin and Sutton and Pollok have discussed gender-specific

inequalities within internet-based political activism.6,7 Keller has studied young

womens blogs and explored how this medium provides a space to express political

and feminist views.8 Harris has identified that online spaces provide less intimidating opportunities for young women to act as citizens than traditional media forms,

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

Shelley Budgeon, Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Gender in Late Modernity

(Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), pp. 156 181.

Wendy Larner and Maria Butler, Governmentalities of Local Partnerships: The Rise of a

Partnering State in New Zealand, Studies in Political Economy, Vol. 75 (2005),

pp. 85 108.

Sarah Maddison and Greg Martin, Introduction to Surviving Neoliberalism: The Persistence of Australian Social Movements, Social Movement Studies, Vol. 9, No. 2 (2010),

pp. 101 120.

Janet Morahan-Martin, Women and the Internet: Promise and Perils, Cyber Psychology and

Behavior, Vol. 3, No. 5 (2000), pp. 683 691.

Jo Sutton and Scarlet Pollok, Online Activism for Womens Rights, Cyber Psychology and

Behavior, Vol. 3, No. 5 (2000), pp. 699 706.

Jessalynn Marie Keller, Virtual Feminisms, Information, Communication and Society,

Vol. 15, No. 3 (2011), pp. 429 447.

10

Political Science 65(1)

and Garrison has highlighted the internets advantage for feminist girls to use a

space that is not controlled by adults.9,10

Overall, the importance and potential of the internet for active citizenship and

political engagement has attracted increasing academic attention over the last 15 years

and generated much interest on two issues in particular. First, authors have discussed

how far online activism can reach into the real world, and thus count as political

participation.11 Some authors described online activism as slacktivism, which has little

impact on political decisions and potentially distracts from more effective forms of

participation.12 Others have argued the opposite, stating that activities such as managing

a Facebook account have wrongly been neglected by traditional research on political

participation.13 Second, much research has investigated with differing results how

political offline and online activities relate to each other and how internet use enhances

or hinders traditional political participation (e.g. voting, attending street protests).14

Disagreements on these questions are often accompanied by differing definitions of

political participation as well as incoherencies regarding what forms of activities are

addressed as online activism.15 Regarding this last issue, Theocharis has offered a useful

differentiation between online tools of the pre- and post-Web 2.0 era.16 He has described

Web 2.0 as a web platform that can accommodate interactive information sharing,

interoperability, user-centred design and collaboration on the World Wide Web, and

is characterized by applications such as video-sharing sites, wikis, blogs and SNS

(e.g. Facebook, YouTube, Twitter). The pre-Web 2.0 era involved fewer interactive

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

Anita Harris, Mind the Gap: Attitudes and Emergent Feminist Politics since the Third

Wave, Australian Feminist Studies, Vol. 25, No. 66 (2010), pp. 475 484.

Ednie Kaeh Garrison, US Feminism Grrrl Style! Youth (Sub)Cultures and the Technologics of the Third Wave, Feminist Studies, Vol. 26, No. 1 (2000), pp. 141 170.

Sonja Livingstone, Magdalena Bober and Ellen J. Helsper, Active Participation or Just

More Information?, Information, Communication and Society, Vol. 8, No. 3 (2005),

pp. 287 314; W. Lance Bennett, Changing Citizenship in the Digital Age, in W. Lance

Bennett (ed.), Civic Life Online: Learning How Digital Media Can Engage Youth

(Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007).

Henrik S. Christensen, Political Activities on the Internet: Slacktivism or Political Participation by Other Means?, First Monday, Vol. 16, Nos 2 7 (2011). Available at:

firstmonday.org.

Kristoffer Holt, Adam Shehata, Jesper Stromback and Elisabet Ljungberg, Age and the

Effect of News Media Attention and Social Media Use on Political Interest and Participation: Do Social Media Function as Leveller?, European Journal of Communication,

Vol. 28, No. 1 (2013), p. 31.

M. Kent Jennings and Vicki Zeitner, Internet Use and Civic Engagement: A Longitudinal

Analysis, Public Opinion Quarterly, Vol. 67, No. 3 (2003), pp. 311 334; Dietram A.

Scheufele and Matthew C. Nisbet, Being a Citizen Online: New Opportunities and Dead

Ends, Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, Vol. 7, No. 3 (2002), pp. 55 75.

Jose Marichal, Political Facebook Groups: Micro-Activism and the Digital Front Stage,

presented at the Internet, Politics, Policy 2010 Conference, Oxford, September 2010.

Yannis Theocharis, Cuts, Tweets, Solidarity and Mobilisation: How the Internet Shaped the

Student Occupations, Parliamentary Affairs, Vol. 65, No. 1 (2012), p. 167.

Schuster

11

applications and email. This article builds on this differentiation and addresses the use of

Web 2.0 online tools for political purposes as online activism. Much research on online

activism (cyberactivism) discusses the digital divide, stating that internet access is not

equally distributed within populations but concentrated among the young and privileged.

Therefore, the literature on cyberactivism has a strong focus on young peoples online

behaviour,17 which is contrasted to the preference of older generations for political participation through traditional media and information sources.18 However, with the

exceptions of Harris and Poltat, who have indicated that online activism can be out

of sight to outsiders19 and is not publicized enough,20 the existing literature leaves room

for investigating how generational differences of internet use might affect communication between activists of different ages. In this article, I argue that online activism significantly affects this intergenerational communication in a way that has negative

outcomes for the feminist movement in New Zealand.

Wave relations

While some authors insist that contemporary feminism is not a new distinctive wave,21

other scholars criticize it for adopting approaches too different from the second wave.22

Thus the very existence of a new third wave of feminism is contested. For this articles

purpose of contrasting two generations, the wave metaphor seems useful nevertheless.

Literature defines the third-wave generation as consisting of feminists who were born

after the 1960s and have been active since the 1990s,23 and emphasizes differences

between womens interests as the central theme of this heterogeneous wave.24 This is

largely because third-wave feminism is rooted in and overlaps with the development

of intersectional questions originally raised by feminists of colour about the essentialism

of white Western feminism.25 Theoretical perspectives associated with this wave include

17.

18.

19.

20.

21.

22.

23.

24.

25.

Livingstone et al., Active Participation or Just More Information?, pp. 287 314; Tom P.

Bakker and Claes deVreese, Good News for the Future? Young People, Internet Use, and

Political Participation, Communication Research, Vol. 38, No. 4 (2011), pp. 451 470.

Holt et al., Age and the Effect of News Media Attention and Social Media Use in Political

Interest and Participation, pp. 19 34.

Harris, Mind the Gap, p. 479.

Rabia K. Polat, The Internet and Political Participation: Exploring the Explanatory Links,

European Journal of Communication, Vol. 20, No. 4 (2005), pp. 435 459.

Cathryn Bailey, Making Waves and Drawing Lines: The Politics of Defining Vicissitudes

of Feminism, Hypatia, Vol. 12, No. 3 (1997), pp. 17 28.

Jenny Coleman, An Introduction to Feminisms in a Postfeminist Age, Womens Studies

Journal, Vol. 23, No. 2 (2009), pp. 3 13.

Leslie Heywood and Jennifer Drake, Its All about the Benjamins: Economic Determinants of Third Wave Feminism in the United States, in Stacy Gillis and Gillian Howie

(eds), Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration (New York: Palgrave Macmillan,

2007). pp. 115 124.

Catherine Harnois, Re-presenting Feminisms: Past, Present, Future, National Womens

Studies Association Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1 (2008), pp. 120 145.

Budgeon, Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Gender in Late Modernity, p. 8.

12

Political Science 65(1)

postcolonial, intersectional and sometimes even post-feminist influences. Thus feminists

who identify with the third wave take diverse approaches but they often critique how

Western feminism has failed to address differences between women appropriately and

seek to overcome such failures. While third wavers also apply this form of selfreflection to their own work, much of the critique refers to the second wave. Given that

many representatives of this earlier generation have put much time, energy and commitment into achieving the feminist goals of the second-wave movement, it is not surprising

that they often do not welcome criticism by third-wave feminists, who tend to be much

younger and arguably less experienced in political struggles. Conversely, third-wave

concepts such as lipstick-feminism, DIY-feminism and cyber-feminism are frequently criticized by older generations for being apolitical26 or regressive.27 Moreover,

a combination of neoliberal thought and third waves own expectations of incorporating

individual differences between women has led to highly individualized forms of feminism that allegedly contradict second-wave attempts to enhance a collective movement.28

Thus young feminists often struggle to have their work and activism taken seriously by

some second-wave representatives.

Generational differences have always existed within feminism. But unlike the second

wave, which started after the first wave had ended, third and second wavers exist

simultaneously.29 Thus, third wavers not only have to defend their values against a

mainstream society that proclaims the emergence of post-feminism and negates the

necessity for feminist activism at all, they also have to negotiate with the previous generation the direction that feminism should take.30

These preconditions need to be considered when analysing how the two generations

understand each others methods of political participation. It could be expected that

young feminists choose a form of organizing that allows them to network among

themselves and avoid the critique of second-wave representatives. However, one central

aim of third-wave feminism is to be inclusive.31 While this inclusiveness originally

referred to ethnic diversity, the concept has expanded to other (if not all thinkable) social

categories such as class, sexual identities, dis/abilities and age. Therefore, it could be

expected that young feminists put effort into making their activism accessible to all interested groups, including older feminists. Following this second argument, the choice of

online activism as a preferred tool of networking and organizing contradicts the aim

of being inclusive, if it contributes

as I hypothesize

to the young feminists

26.

27.

28.

29.

30.

31.

Coleman, An Introduction to Feminisms in a Postfeminist Age, pp. 3 13.

Susann Archer Mann and Douglas J. Huffman, The Decentering of Second Wave Feminism

and the Rise of the Third Wave, Science and Society, Vol. 69, No. 1 (2005), pp. 56 91.

Harris, Mind the Gap, p. 477.

Feminism did not pause between waves. Here the wave metaphor refers to exceptionally

vocal periods of feminism.

Amber E. Kinser, Negotiating Spaces For/Through Third-Wave Feminism, Feminist

Formations, Vol. 16, No. 3 (2004), pp. 124 153.

Naomi Zack, Inclusive Feminism: A Third Wave Theory of Womens Commonality

(Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2005).

Schuster

13

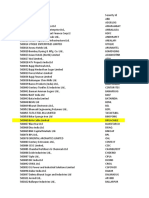

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Age

20

30

40

50

60

29

39

49

59

70

Ethnicitya

Sexual identityb

17

11

3

6

3

Pakeha/Europeanc

Asiand

Maori

Samoan

31

8

5

1

Hetero

Queer

Lesbian

Bi-sexual

(Unknown

25

7

5

1

2)

Notes

a

Multiple answers possible.

b

I did not ask about their sexual identity, but most of the women referred to it during the interview.

c

Includes European decent New Zealander (Pakeha), Australian, diverse European, Northern American.

d

Includes Chinese, Filipino, Indonesian, Malay, Singaporean, Sri Lankan, Vietnamese.

invisibility. With these two possible explanations in mind it seems worthwhile to examine the inclusiveness and visibility (or lack thereof) of feminist online activism.

Methodology

This research is guided by a feminist methodology that draws on standpoint theory,32 and

thus links its quest for knowledge with supporting the political struggles of women.

Therefore, the motivation to discuss a generational divide between feminists is not to

highlight incompatibilities but to help eradicate misunderstandings. Findings are based

on 40 qualitative interviews with women of all ages who actively engaged with womens

political issues or feminist activism in Auckland and Wellington. The interviews are part

of a broader PhD project by the author, based at the University of Auckland, that

examines the nature of the contemporary womens movement in New Zealand. The

sampling procedure was based on email-snowballing. The initial call for participants was

emailed to a first set of womens organizations and recipients kept forwarding it within

their personal networks. This produced over 70 responses by interested women from all

over New Zealand. The selection of 40 participants was intended to maximize diversity

among interviewees according to their age, ethnicity and forms of feminist engagements.

Other criteria, such as sexual identity and occupation were not primary sampling criteria

but where possible they were used to increase diversity in these areas too. Table 1 shows

the distribution of a first set of sample characteristics. Overall, the sample reflects an

adequate level of diversity, but I acknowledge a disappointingly small number of Pacific

Island women among the participants.

Most interviewees (34) self-identified as feminist. Among the six women who did

not adopt this label fully only two rejected the label entirely both of them were 35

years or older. The remaining four women expressed that they maybe, sometimes

32.

Standpoint theory considers social power dynamics as a crucial part in the production of

knowledge: for example, Sandra Harding, Strong Objectivity: A Response to the New

Objectivity Question, Synthese, Vol. 104, No. 3 (1995 ), pp. 331 349.

14

Political Science 65(1)

Table 2. Forms of feminist engagement (multiple memberships possible; n).

Activist/grassroots group (e.g. anarcha-feminism, protest/rally

organization)

Formal institution (e.g. National Council of Women, Maori

Womens Welfare League)

Service provider for women (e.g. Auckland Womens Centre,

Rape Prevention Education)

Non-political womens group (e.g. church group, choir)

University club/politics (e.g. feminist club, womens rights office)

Governmental institution (e.g. Ministry of Womens Affairs)

23

12

8

7

6

2

or not often identified as feminist, depending on the respective circumstances. Given

the sensitivity around issues of self-identification of feminists today,33 this article

reflects 7 differences of feminist identification among participants by addressing the

younger group of women (who all adopted the label at least sometimes) as feminists,

while refraining from doing so for the older group. Independently of their feminist identification, ways and means of political participation varied widely among all participants. They engaged in numerous activities that aimed for empowerment of women

and reflected what Inglehart and Norris34 referred to as traditional political activism

(e.g. state-oriented, union membership), civic activism (e.g. through voluntary/community organizations) or protest activism (e.g. demonstrations, petitioning). Table 2 shows

the participants affiliations with womens organizations/groups. These memberships

embedded most activities the women named when asked how they engaged with feminist

or political womens issues.

Thematic analysis35 and NVivo 9 software directed the analysis of the interview

transcripts. It must be emphasized that this is a qualitative study and therefore,

percentages (Figure 1) should only be interpreted as showing general trends.

Before discussing intergenerational differences, this article needs to define generations, and in reference to the literature on the digital age divide feminist generations are

differentiated based on age cohorts.36 The terms younger and older women serve as a

way to distinguish between 20 31 and 32 70-year-old participants. While the age span

in the older group is larger than in the younger group, the age of 31 was chosen as a

33.

34.

35.

36.

Loreen N. Olson, Tina A. Coffelt, Eileen Berlin Ray et al., Im all for equal rights, but

dont call me feminist: Identity Dilemmas in Young Adults Discursive Representation of

Being a Feminist, Womens Studies in Communication, Vol. 31, No. 1 (2008), pp.

104 132.

Ronald Inglehart and Pippa Norris, Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change

around the World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), pp. 101 126.

Dennis Howitt, Introduction to Qualitative Methods in Psychology (Harlow: Pearson

Education Limited, 2010), pp. 163 187.

Fadi Hirzalla and Liesbet vanZoonen, Beyond the Online/Offline Divide: How Youths

Online and Offline Civic Activities Converge, Social Science Computer Review, Vol. 29,

No. 4 (2011), pp. 481 498.

20-31 years old (n=22)

low

medium

high

high

in %

100

90

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

low

15

medium

Schuster

32-70 years old (n=18)

Figure 1. Internet affinity by age group.

threshold because it is the median age among the participants. Age 31 also roughly

divides the sample into women who participated in online communities and those who

did not.

Young womens use of social media

Building on Bakker and deVreeses finding that political participation differs

for consumers of different media types (especially between online and offline media

users),37 the distribution of internet affinity among participants is used as a first

indicator to suggest that online activism is dividing the generations (Figure 1). I understand internet affinity to be the participants level of internet use for political purposes

and as an information source for feminist issues. A low level of internet affinity is assigned

to women who did not mention the use of tools such as Facebook, Tumblr or Twitter at all

or primarily used other sources. A medium level refers to participants who talked, for

example, about the use of email newsletters or occasional Facebook posts but also mentioned other tools and sources in their narratives. The group of women with a high internet

affinity talked about the internet as their (almost) exclusive way of informing themselves

about feminism and organizing activism. They expressed I read a lot of blogs and I have

an RSS feed thats twelve miles long (Judith, 21), Im just like online, online, online and

so books, huh? Yeah, thats how I get my information, online really. Facebook and the

wider internet (Nana, 28) or I guess I read that [Tumblr] pretty much every day. Like, I

wake up and check my phone and have a scroll through it (Gabriela, 25).38

The almost symmetrical pattern in Figure 1 illustrates that younger women showed a

greater affinity for online tools, social media and the internet than older women. This is

not particularly surprising because digital literacy is usually higher among younger

37.

38.

Bakker and deVreese, Good News for the Future?, pp. 451 470.

All participant names are pseudonyms.

16

Political Science 65(1)

people.39 However, the figure serves as first evidence that the online world is not shared

equally by all generations. I argue that this is partly because the young women use the

internet not only for their daily non-political communication and as an information

source but also for their feminist activities. Advocate for young womens empowerment

and author Lee stated that the internet has revolutionized the way we organize and that

it was particularly effective in serving a womens political agenda.40 I will explore in

the following what that meant for the participants.

New media for feminist participation

Web 2.0 can be applied in several ways for political purposes.41 Using social media to

raise awareness about certain issues (e.g. current political events) has been labelled

microactivism42 and was described by the participants as a welcome way of political

participation that required a low level of involvement. This was important to many who

either did not have a lot of time to engage deeply with activism or who had only

recently become interested in feminism and wanted an easy and accessible way to get

involved. While raising awareness has little direct or immediate effect on social

change, some interviewees stated that posting links to feminist online articles, videos

and related items on Facebook pages should not be underestimated. Djamila (21) said:

I just think its really important. And although there are a lot of people that would just

sort of scroll up . . . I just think its important to get the message out. Djamila was not

the only participant who saw great value in getting the message out. Facebook

seemed ideal for that purpose because it is a medium that a great number of young

people use daily.

Feminist blogs are another popular way of raising awareness and sharing information. They require more involvement because they need to be updated regularly and often

include extensive essays and commentaries on mainly current political and/or feminist

issues. In the New Zealand context, the blog called The Hand Mirror, written by a

collective of New Zealand-based feminist women, is of particular importance.43 Going

for over five years, it has a comparatively long lifespan for a blog and 13 participants

either read it or write for it which is remarkable for a New Zealand blog, given that

the internet offers countless international alternatives.

Facebook pages and blogs both provide a platform for discussions. Readers can leave

comments, share ideas and post critiques. Thus the young women engaged vividly with

39.

40.

41.

42.

43.

David Buckingham and Rebekah Willett, Digital Generations: Children, Young People and

New Media (Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum, 2006).

Shireen Lee, The New Girls Network: Women, Technology, and Feminism, in Vivien

Labaton and Dawn Lundy Martin (eds), The Fire this Time: Young Activists and the New

Feminism (New York: Anchor Books, 2004), p. 100.

Jody C. Baumgartner and Jonathan S. Morris, MyFaceTube Politics: Social Networking

Websites and Political Engagement of Young Adults, Social Science Computer Review,

Vol. 28, No. 1 (2010), pp. 24 44.

Marichal, Political Facebook Groups.

The Hand Mirror, available at: http://thehandmirror.blogspot.co.nz/.

Schuster

17

each other and formed online communities. While some authors have been sceptical

about how online networking can build meaningful communities,44 Harris has argued

that Web 2.0 tools provide favourable opportunities, especially for young women, to

produce public selves.45 The women interviewed tended to value such communities

highly. For example, Betty (31) expressed how important online relationships were for

her:

This [online] was how I connected with people who were feminist cos I didnt know any . . . I

connected pretty much with online feminists until I could find feminists in New Zealand. But

its amazing to have feminist friends! I remember for a very long time I used to feel very

lonely being a feminist . . . So yeah, it was really amazing to connect with a whole lot of

feminists.

Like Betty, other participants pointed out how the internet helped them not to feel

isolated as a feminist. A few young women mentioned that declaring themselves to be

feminists was met by a lack of understanding among their friends and so they had no

real world peers to talk to about feminism. For a young mother with financial difficulties it was hard to find opportunities to go out and meet other feminists. All of them

appreciated the internet for providing avenues to communicate with other like-minded

women, which made them feel less isolated.

At the same time, debates around slacktivism and the relation of online and offline

activism provide arguments that online conversations and discussions do not count as

political participation in the real world.46 But the young women did not confine

themselves to discussions alone; they also used social media to organize events outside

the internet. Such events covered one-off protests and pickets as well as continuing the

work of collectives and groups. For example, the planning of the SlutWalk47 in 2011

happened almost entirely online, as Judith (21), one of the organizers, explained: SlutWalk was a totally online pushed thing. We had no I think Auckland might have but

Wellington had no posters up. We were totally off the back of Facebook and Twitter and

we had 1200 people just in Wellington!

Like SlutWalk, the Hollaback Wellington project connects online with offline

activism. Its website explains what this collective does:

Hollaback is a network of blogs and several mobile applications. Through this technology,

individuals can submit stories of their experiences of street harassment. We then mark them

using the Google Maps API on a map of Wellington so that we can all see where these events

occurred and begin to break the silence around this form of gender-based violence.48

44.

45.

46.

47.

48.

Cf. Keller, Virtual Feminisms, pp. 429 447.

Harris, Mind the Gap, p. 479.

E.g. Christensen, Political Activities on the Internet.

SlutWalk is an international series of protest marches that started in Toronto in 2011 as a

response to a police officer advising women not to dress like sluts.

Hollaback Wellington, available at: http://wellington.ihollaback.org/.

18

Political Science 65(1)

All of the Hollaback collectives work is online, but this work is, at its core, about

engaging with the community for a feminist cause. Similarly, Eats on Feets New Zealand

which is a collective organized by young women that matches mothers who have an

oversupply of breast milk with parents who have an undersupply

does not have a

physical space, but runs a Facebook page to serve as a platform for connecting parents.49

Advantages and disadvantages

There are many reasons why online tools are the preferred way of participating for young

women. Most young people are familiar with internet services because they use them for

other (non-political) purposes too, often on a daily basis. The women in this study also

emphasized that social media are easily accessible and low in cost. This was important

for many young women often students but also young mothers who did not have

large financial resources. Moreover, as Harris has pointed out, social networking tools

provide places where young women can express both personal and political views and

connect with diverse others.50 They can operate as safe spaces from which young

women speak out. Similarly, Keller has argued that young women use blogs as platforms because there are not many other spaces available for them to speak out and

discuss their opinions on political issues.51 Many participants described online forums as

powerful ways to have conversations, especially about sensitive topics such as sexual

abuse. Online platforms offer spaces where women can share traumatic experiences with

others who have similar stories and they can discuss, for example, what a feminist

response to rape culture societies can look like. Unlike any real world forum or event,

the women can choose how much of their identity they want to unveil online. A few

participants even argued that for some people going online might be the only way to

engage with such issues. Djamila (21), who had experienced harassment in the past,

explained why she did not go to street protests but was active online: Cos its a lot less

daunting. Its easy to just put stuff on Facebook whereas, you know, when you go out

there. You dont have to tolerate peoples abuses or whatever. Judith (21) had a similar

thought:

And not everyone is in a position where they can go out and talk about that [sexual assault]. Not

everybody is in a position where, you know . . . I read the blog quite regularly of a very lovely

transgender woman who is not out. Who would have a lot of personal risks when she came out.

She is not in the position, she couldnt go to SlutWalk because she didnt feel safe.

The possibility of staying anonymous in online communities by using nicknames was

highlighted by several participants as an advantage and has also been identified as

beneficial for participation by scholars such as Anduiza, Cantijoch and Gallego.52

49.

50.

51.

52.

Eats on Feets New Zealand, http://www.facebook.com/eatsonfeetsnz.

Harris, Mind the Gap, p. 480.

Keller, Virtual Feminisms, pp. 429 447.

Eva Anduiza, Marta Cantijoch and Aina Gallego, Political Participation and the Internet,

Information, Communication and Society, Vol. 12, No. 6 (2009), p. 866.

Schuster

19

Another advantage of online participation mentioned by the participants was that its

flexibility worked well with busy time schedules. As opposed to real world events,

which happen at a certain time at a certain place, women can go online at any time. A

young single mother mentioned how she could not attend evening meetings of activist

groups that she was part of, or participate in the SlutWalk, because of her caretaking

duties. However, she was the administrator of a collectives Facebook page. Thus online

activism enabled her to take on a central role in her collective. Other participants told

similar stories of how they could not be part of traditional protests or pickets because

they did not feel comfortable bringing children. Some women with limited time

resources prioritized fulfilling their family responsibilities over attending group meetings. In these instances, online participation specifically allowed young mothers

a

group that often finds it difficult to participate in activism to engage deeply and take

on leadership roles.

Younger women also found that social media enhanced their ability to network on a

regional, national and international level. They emphasized that some of their projects

(e.g. Hollaback, SlutWalk) had initially started overseas but spread to many other

countries via online networks. Facebook also enabled groups to have members in different parts of the world, which was particularly interesting for small collectives such as

Young Asian Feminists Aotearoa who maintained relationships with Asian feminists

overseas. Other participants were particularly enthused about the ability to connect with

women in different parts of New Zealand or to re-establish connections with activists

they used to know from past projects.

The online world, of course, has some disadvantages when compared to the real

world. For example, some young women encountered severe criticism of their opinions

or events through online platforms. It seems that the immediate and often anonymous

character of the online environment can attract personal and unfiltered feedback. SlutWalk, for instance, provoked some controversial debates53 and the organizers were

heavily criticized, as Gabriela (25) reported: I took it [the criticism] really, really to

heart and I remember the week after The Hand Mirror did a post and people commented on it and I just . . . You know, I was at work and I started crying and it was just

too much criticism.

Personal criticism and, in an extreme form, online harassment are certainly issues that

relate not only to online activism but to many aspects of the digital world, especially

among young people.54 Morahan-Martin has argued that women are particularly affected

by hostile online climates because of gendered communication styles.55 The harsh

critique that some of the young women of my study faced online led some of them to

reconsider their involvement in future feminist activism. Thus there is reason to argue

that the use of online tools can also have debilitating effects on a feminist movement.

53.

54.

55.

Ellena Savage, Politics of Slutwalk, Eureka Street, Vol. 21, No. 10 (2011), pp. 29 30.

Janis Wolak, Kimberly J. Mitchell and David Finkelhor, Does Online Harassment Constitute Bullying? An Exploration of Online Harassment by Known Peers and Online-Only

Contacts, Journal of Adolescent Health, Vol. 41, No. 6 (2007), pp. 51 58.

Morahan-Martin, Women and the Internet: Promise and Perils, p. 683.

20

Political Science 65(1)

A generational divide

The disadvantage of online activism that is of importance for the intergenerational

relationship of feminists is the exclusionary character of social networking. Summarizing the core of the problem, Rebecca (34) stated: For some people, they just dont

communicate online at all and they dont get it and as a result it can be quite exclusionary. This characteristic of online tools has been identified by other scholars. For

example, Chamberlain claimed: Online activism is inherently exclusive because it has

as a prerequisite access to the right technology.56 For the participants of this study,

exclusiveness referred more to habits of communicating than to opportunities of access.

Theoretically, all participants had access to setting up a Facebook account, for example,

and thus could participate if they chose. However, social media only connects people

who actively sign up to it and it cannot reach beyond its own scope. While a link to a

Facebook page can be forwarded to someone who does not participate in online communities, most information on Facebook can only be accessed after logging in with a

user name and password. Therefore, people who do not decide to participate actively

have a low chance of receiving the same information and knowing about activities that

are entirely organized online. This makes it, even if unintentionally, a very exclusive

environment.

These online communities tend to be young. Although some of the younger participants did not know the purpose of blogs and some older participants were using Twitter

and Facebook, on the whole women in their early thirties and over were less likely to

engage with online activism than younger participants. Such an age divide can become a

problem when the online-based activities of young women are hidden from older

women. Many women interviewed confirmed this invisibility: several older participants

did not know about the existence of the younger womens activities and they were worried that once their own generation had retired from feminist struggles there would be no

(or not enough) young women to continue their work. For example, Lily (51) was particularly concerned about the low participation of young women in activities she

engaged with herself. She said: I mean, we used to have workshops and all sorts of

things. Where are they now? Her concern was shared with other women of the older

generation who worried that young women in New Zealand no longer saw a need for

feminism.

Based on the explanations of the participants who engaged with online activism,

I argue that there are many more young feminists in New Zealand who are hidden

online than older participants assume. The problem with this invisibility is that it not only

reinforces the stereotype of the politically uninterested young female but it is also disadvantageous at a broader political level, as Alice (24) articulated:

Because you [older feminists] cant see them [younger feminists], you keep on saying that they

dont exist. And its disheartening to say that because you are actually putting the movement

56.

Kristen Chamberlain, Redefining Cyberactivism: The Future of Online Project, Review of

Communication, Vol. 3, Nos 3 4 (2004), p. 145.

Schuster

21

back. Like, you know, young women would sit there and be like Ah yeah, I am all alone, why

shouldnt I give up?

Alices harsh critique has a reasoned underlying argument: repeatedly telling

young women (and the wider public) that there are no young feminists in New Zealand

might alienate those who become interested in feminism and discourage people who

considered joining a feminist movement. As shown earlier, some of the young women

interviewed felt isolated as feminists in the real world. Any support of the notion that

feminism is not of interest to modern young women potentially reinforces such isolation.

It is not only the older generation that seem to have difficulties connecting with

their younger feminist counterparts. Many of the younger participants expressed

disappointment that there are too few opportunities to work with older women, which

was partly because they did not know where to find them. Betty (31), who had enjoyed

working with older women in the past, explained: But I actually, admittedly, I have

almost no idea how to connect with them now, you know. Cos they are also not easy to

find online, cos they are less likely to be online. Meanwhile, 25-year-old Gabriela, when

asked whether she thought that New Zealand had a current womens movement, said: I

guess there is a movement but it feels really small and it feels like its generally just people of my age. This statement indicates that she had little knowledge about how and

where older women engaged with feminist work.

Of course, young and older feminists are not entirely disconnected from each other.

However, in their conversations about online activism they sometimes seem to be at

cross-purposes. For example, Susan (23) talked in her interview about a discussion

among activists on how to mobilize around abortion law reform, which was attended

by activists of all ages:

You know, you start talking about Twitter or something and people will be like Oh, I dont

know, you know. The older women would definitely feel . . . I think you could notice that they

felt excluded from that conversation. Whereas it was something that was quite exciting to those

of us who have done online stuff. Which tended to be the younger.

A 25-year-old member of the Wellington Young Feminist Collective (WYFC)

told a similar story about an encounter this collective had with an older female researcher

who asked them about their ways of working:

A lot of the stuff that we were saying was about how we do a lot of stuff online and thats what

we do. It was almost like she was invalidating that and being like OK I get that you have a

Facebook page but what else do you do? And we were like Well, the Facebook part is actually

the biggest component of the work that we do.

These two quotes illustrate that the young women encountered a certain level of

unease among older women about online activism as a form of political engagement.

Susan even used the phrase they felt excluded to describe their experience. The quote

by the WYFC member further shows that this feeling of exclusion is associated with

different understandings of what counts as valid political participation. The question

what else do you do? indicates that running a Facebook page is not understood as an

22

Political Science 65(1)

activity that can stand alone as the purpose of a feminist collective, which reflects

debates discussed earlier within the literature on the legitimacy of online activism.

Disconnected generations?

Many of the younger participants reported how frustrating, discouraging and upsetting it

was to be told that they the young feminists of New Zealand did not exist. At the

same time, older participants commented on how disheartening, worrying and disappointing it was that they did not see enough young women engaging with feminism. It

is important for feminist and political science research to explore this lack of intergenerational contact and its causes. There is reason to argue that positive relationships

between generations within movements can enhance recruitment and the growth of

organizations and projects.57 Therefore, an improvement in intergenerational relationships between feminists promises to strengthen the overall womens movement.

Furthermore, increasing academic evidence shows that decline in traditional and

formal forms of political participation among young people does not suggest a lack of

interest in politics, but rather a different focus for their interests.58 The exclusive manner

in which the young women in this study used social media for their political work was

not intentional online was simply a space in which members of their generation spent

much of their time. Similarly, the older generation did not grow up in the digital age and

kept looking for their successors within the social networks that they knew. Both generations work within the systems they are familiar with and although they overlap in

time, they often use different sets of methods and approaches. As this discussion of

online activism has shown, such differences in methods can enhance the invisibility of

young feminists work.

Of course, generational differences among feminists are complex and there is more to

them than just two generations that do not meet because one is online and the other is not.

The second and the third wave differ in their values and methods, as well as in their

definitions of feminism. However, there is also reason to argue that they share many

underlying aims and ideas about equality and the improvement of womens lives.59 With

the example of an Australian programme for young mothers, Maddison has discussed

how intergenerational feminism can be successful.60 Her study has highlighted the

importance of the programmes focus on reciprocity between young and older women.

In the same way, Budgeon has suggested that contemporary feminism needs to move

57.

58.

59.

60.

Beth E. Schneider, Political Generations and the Contemporary Womens Movement,

Sociological Inquiry, Vol. 85, No. 1 (1988), p. 17.

Matt Henn, Mark Weinstein and Dominic Wring, A Generation Apart? Youth and Political

Participation in Britain Today, paper presented at the 50th Annual Conference of the

Political Studies Association, London, 2000, p. 4.

Lauren Duncan, Womens Relationship to Feminism: Effects of Generation and Feminist

Self-Labeling, Psychology of Women Quarterly, Vol. 34, No. 4 (2010), p. 505.

Sarah Maddison, A Part of Living Feminism: Intergenerational Feminism in a Working

Class Area, Journal of Interdisciplinary Gender Studies, Vol. 8, Nos 1 2 (2004), pp.

38 54.

Schuster

23

away from an understanding of a linear movement, with one wave following the next,

successively building up on previous achievements.61 Instead of feminist achievements

being only passed on, they could also be passed back.62

This is already happening in New Zealand to some degree. While this article has

discussed some worrying differences between generations, it needs to be emphasized

that there are many collaborations of younger and older women that work well. There are

organizations (e.g. Rape Crisis Education) and activist groups (e.g. groups concerned

with abortion law) that successfully combine the efforts of women of many ages.

Some participants also named instances of the two generations agreeing on the issue of

online participation. Elisabeth (60), for example, talked about the media presence of the

National Council of Women of New Zealand (NCWNZ), which has a reputation for

being mainly constituted by older members: And I know some of the young members of

the Auckland branch, they would like them to update . . . with media and social media

and technology. And I think the national organization is taking that on board. Indeed,

the updated website of the NCWNZ offers links to their Facebook page, Twitter account

and YouTube presence.63

Conclusion

There are several reasons why the activities of young feminists, often referred to as the

third wave, remain unseen by the wider public, including older women engaging with

feminism. This article has focused on one such aspect. It has asked whether young

womens use of social media for political participation and feminist activism has contributed to such invisibility.

Based on findings from interviews with women in New Zealand who engaged with

feminism, I have argued that social media served as a useful tool for the young womens

political activities. The young women employed new media such as Facebook, Twitter

or blogs in their political activities because of easy access, low costs and flexible

applications. However, since most information shared via social media is only available

for people who actively sign up to it, online activism unintentionally excludes those who

do not engage in online communities. Among the participants, this latter group tended to

be the older women. They often did not know about many feminist activities that the

younger women engaged in, and thus were disappointed about the lack of feminist

commitment among young women in New Zealand. At the same time, the strong focus of

some younger women on online participation resulted in their lack of awareness of older

womens activities and work. As a consequence, it seemed that the generational divide

among feminists in New Zealand had been facilitated by age-specific ways of communicating and organizing events.

Although the literature on the inclusiveness of third-wave feminism might suggest that

young feminists work against the exclusionary character of online activism, overall this

61.

62.

63.

Budgeon, Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Gender in Late Modernity, p. 156.

Budgeon, Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Gender in Late Modernity, p. 157.

The National Council of Women of New Zealand, available at: www.ncwnz.org.nz/.

24

Political Science 65(1)

does not seem to be the case among the participants. However, as the example of the

NCWNZ has shown, there is reason to be optimistic that differences and problems caused

by the use of social media will decrease in the future. Moreover, many of the young participants were only in their early twenties, and had been actively engaged with feminism

for only a few years. At such a young age they cannot be expected to have found a way of

participating in feminism that is flawless, powerful and visible. But they have realized that

online activism alienates some of their older feminist peers, which is a good starting point

for advancing intergenerational relationships. At the same time, increasing digital literacy

across generations will possibly change the understanding among feminists of all ages of

how useful online activism can be for feminist work. Research can provide deeper insights

into the impact of online activism on the womens movement, for example by incorporating the perspective of mid- wavers and investigating the digital divide (not only reflecting age but also rural/urban, ethnic and class cleavages) or issues of online harassment in

relation to feminist activism. It is hoped that these developments will enhance the visibility

of young womens political participation and by extension the presence of contemporary

feminism in New Zealand and other parts of the world.

Author note

An earlier version of this paper has been presented at the 2012 NZPSA conference special panel:

Where are the women in public life?, 26 28 November, Wellington.

Author biography

Julia Schuster studied Sociology at the University of Vienna in Austria and has worked

as a research assistant at the Austrian Academy of Sciences. In 2010 she joined the

Department of Sociology at the University of Auckland as a PhD candidate and is

working on her thesis which examines the contemporary womens movement in New

Zealand. Her research interests include feminist activism, intersectionality and social

movements.

You might also like

- Internet Social Movement Muslim PDFDocument21 pagesInternet Social Movement Muslim PDFEl MarcelokoNo ratings yet

- Gender JusticeDocument14 pagesGender JusticeSw sneha 18No ratings yet

- Review of Related Literature in Arellano Elisa Esguerra Campus in Practical Research-1 Effects of Social Media On Political StanceDocument6 pagesReview of Related Literature in Arellano Elisa Esguerra Campus in Practical Research-1 Effects of Social Media On Political StanceKelvin Benjamin RegisNo ratings yet

- Analyzing Women's Movements and Collective ActionDocument24 pagesAnalyzing Women's Movements and Collective ActionrichvanwinkleNo ratings yet

- Feminism EssayDocument7 pagesFeminism EssayHalima AhmedNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of How US Advocacy Groups Perceive and Use Social Media Tools PDFDocument25 pagesAn Analysis of How US Advocacy Groups Perceive and Use Social Media Tools PDFangryTXNo ratings yet

- 34pakistan Social Sciences ReviewDocument11 pages34pakistan Social Sciences ReviewMuhammad ShahbazNo ratings yet

- Gender and Politics - WikipediaDocument21 pagesGender and Politics - WikipediaAfaq khanNo ratings yet

- Workable Sisterhood: The Political Journey of Stigmatized Women with HIV/AIDSFrom EverandWorkable Sisterhood: The Political Journey of Stigmatized Women with HIV/AIDSRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Individualising Social Participation and Reconstituting Youth in PolicymakingDocument9 pagesIndividualising Social Participation and Reconstituting Youth in PolicymakinggpnasdemsulselNo ratings yet

- Political Science II Final ProjectDocument12 pagesPolitical Science II Final ProjectHIRENo ratings yet

- Hottest 100 WomenDocument16 pagesHottest 100 WomenRosa ZapataNo ratings yet

- Activism or Slacktivism: Choosing The TopicDocument3 pagesActivism or Slacktivism: Choosing The TopicArghadeep BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Mendes Ringrose Keller Digital Feminist ActivistDocument225 pagesMendes Ringrose Keller Digital Feminist Activistapiejuntillas100% (1)

- Bakker de Vreese 2011Document21 pagesBakker de Vreese 2011mmaria65No ratings yet

- Transforming Gender Identities Through Quota System-Confronting The Question of Women's Representation in PoliticsDocument7 pagesTransforming Gender Identities Through Quota System-Confronting The Question of Women's Representation in Politicsijsrp_orgNo ratings yet

- IndiaDocument20 pagesIndiaDrishti DuttaNo ratings yet

- Brokered Subjects: Sex, Trafficking, and the Politics of FreedomFrom EverandBrokered Subjects: Sex, Trafficking, and the Politics of FreedomRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 1 PBDocument6 pages1 PBHelga Midori IwamotoNo ratings yet

- PR Final Paper Fall 2021 RevisedDocument9 pagesPR Final Paper Fall 2021 Revisedapi-707476482No ratings yet

- BA Politics - VI Sem. Additional Course - New Social MovementsDocument59 pagesBA Politics - VI Sem. Additional Course - New Social MovementsAnil Naidu100% (2)

- Annotated Bibliographies On ElectionsDocument12 pagesAnnotated Bibliographies On ElectionsAngelika May Santos Magtibay-VillapandoNo ratings yet

- Female Politicians in The British Press: The Exception To The Masculine' Norm?Document22 pagesFemale Politicians in The British Press: The Exception To The Masculine' Norm?THEAJEUKNo ratings yet

- History Research Work Sem 5Document31 pagesHistory Research Work Sem 5Priyanka JadhavNo ratings yet

- PS 111 Proposal First DraftDocument38 pagesPS 111 Proposal First DraftMarteCaronoñganNo ratings yet

- #ListenToSurvivorsDocument22 pages#ListenToSurvivorsferiasenzamoraNo ratings yet

- Gil de Zuñiga Et Al., 2011Document18 pagesGil de Zuñiga Et Al., 2011Carolina Constanza RiveraNo ratings yet

- Women and the White House: Gender, Popular Culture, and Presidential PoliticsFrom EverandWomen and the White House: Gender, Popular Culture, and Presidential PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Annotated Bibliography 1Document3 pagesAnnotated Bibliography 1api-508305739No ratings yet

- Cambridge University PressDocument22 pagesCambridge University PressSimon Kévin Baskouda ShelleyNo ratings yet

- Impact of Social Media On Political Polarization and ActivismDocument4 pagesImpact of Social Media On Political Polarization and ActivismiResearchers OnlineNo ratings yet

- Overview of Political BehaviorDocument31 pagesOverview of Political BehaviorPatricia GonzalesNo ratings yet

- Last Name Student's Name Professor's Name Course Number Date Annotated Bibliography and ReflectionDocument7 pagesLast Name Student's Name Professor's Name Course Number Date Annotated Bibliography and ReflectionUsman NarooNo ratings yet

- Social Capitaland Political Participation in Latin America Evidence From Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and PeruDocument32 pagesSocial Capitaland Political Participation in Latin America Evidence From Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and PeruCamod1954No ratings yet

- Media Transformations 10 2013 Full IssueDocument144 pagesMedia Transformations 10 2013 Full IssueRomas SakadolskisNo ratings yet

- Politicians Celebrities and Social Media A Case of InformalisationDocument19 pagesPoliticians Celebrities and Social Media A Case of InformalisationBárbara Prado DíazNo ratings yet

- Social Media in Turkey As A Space For Political Battles: Aktrolls and Other Politically Motivated TrollingDocument17 pagesSocial Media in Turkey As A Space For Political Battles: Aktrolls and Other Politically Motivated TrollinglominolNo ratings yet

- Political CultureDocument13 pagesPolitical CultureMariam BagdavadzeNo ratings yet

- Role of Social Media in Political Socialization of People (A Case Study of District Tank)Document12 pagesRole of Social Media in Political Socialization of People (A Case Study of District Tank)rahim khanNo ratings yet

- Digitalised Societies Week 1 Reading Reflection2Document2 pagesDigitalised Societies Week 1 Reading Reflection2li39841609No ratings yet

- Civil Society's Role in Indonesia's Democratic ConsolidationDocument27 pagesCivil Society's Role in Indonesia's Democratic ConsolidationYuvenalis Dwi KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Political Socialization in the 21st Century Research RecommendationsDocument23 pagesPolitical Socialization in the 21st Century Research RecommendationsSteven BermúdezNo ratings yet

- Political LiteracyDocument9 pagesPolitical LiteracySarah Mae Sumawang CeciliaNo ratings yet

- Policy Futures in Education Volume 11 Number 6 2013 - Activist Academics: what futureDocument12 pagesPolicy Futures in Education Volume 11 Number 6 2013 - Activist Academics: what futureRijnzwindNo ratings yet

- Citizenship Robson Xenos 2014Document18 pagesCitizenship Robson Xenos 2014PakornTongsukNo ratings yet

- Cyberfeminism in China Huan 2Document17 pagesCyberfeminism in China Huan 22017201876No ratings yet

- Digital Observation: An Analysis of Patriarchal Comments in The WebDocument17 pagesDigital Observation: An Analysis of Patriarchal Comments in The WebEduardo J. S. HonoratoNo ratings yet

- Networked Politics - A ReaderDocument238 pagesNetworked Politics - A ReaderÖrsan ŞenalpNo ratings yet

- ArticleDocument18 pagesArticleecauthor5No ratings yet

- On Shifting Ground: Muslim Women in the Global EraFrom EverandOn Shifting Ground: Muslim Women in the Global EraFereshteh Nouraie-SimoneRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Efficacy of Civil Disobedience As Tool For Political Mobilization and Social Action: Lessons From NigeriaDocument19 pagesThe Efficacy of Civil Disobedience As Tool For Political Mobilization and Social Action: Lessons From NigeriaHassan KhanNo ratings yet

- Constructing Public Opinion: How Political Elites Do What They Like and Why We Seem to Go Along with ItFrom EverandConstructing Public Opinion: How Political Elites Do What They Like and Why We Seem to Go Along with ItNo ratings yet

- Bybee Neo-Liberal News For Kids - Citizenship Lessons From Channel OneDocument19 pagesBybee Neo-Liberal News For Kids - Citizenship Lessons From Channel Onebybee7207No ratings yet

- Term Paper On Social MovementsDocument4 pagesTerm Paper On Social Movementsafmzweybsyajeq100% (1)

- SATU KETIK, RIBUAN AKSI: MENGATALISASI PARTISIPASI PEMUDA INDONESIADocument18 pagesSATU KETIK, RIBUAN AKSI: MENGATALISASI PARTISIPASI PEMUDA INDONESIADwi SaputroNo ratings yet

- An Analysis of The Social Media Contents in Forming The Political Attitudes of Social Media UsersDocument326 pagesAn Analysis of The Social Media Contents in Forming The Political Attitudes of Social Media UsersWimble Begonia Bosque100% (1)

- Social Media's Influence on Political Participation and News ConsumptionDocument22 pagesSocial Media's Influence on Political Participation and News ConsumptionchanNelVlog :No ratings yet

- Cleaning Standard Operating ProceduresDocument55 pagesCleaning Standard Operating ProceduresRany Any100% (3)

- NeoPiano ManualDocument19 pagesNeoPiano ManualLaw LeoNo ratings yet

- NRL Autonomous Systems Research Timeline: 1923 - 2012Document12 pagesNRL Autonomous Systems Research Timeline: 1923 - 2012U.S. Naval Research Laboratory0% (1)

- Quantum Frac Gravel Pack SystemDocument2 pagesQuantum Frac Gravel Pack SystemDavide BoreanezeNo ratings yet

- SC2012 VMM DocumentationDocument614 pagesSC2012 VMM DocumentationtithleangNo ratings yet

- Deki Fan Regulators Feb 2012 WebDocument18 pagesDeki Fan Regulators Feb 2012 WebjaijohnkNo ratings yet

- Why I Did It by Nathuram Godse-Court StatementDocument2 pagesWhy I Did It by Nathuram Godse-Court StatementmanatdeathrowNo ratings yet

- Electronic: Whole Brain Learning System Outcome-Based EducationDocument19 pagesElectronic: Whole Brain Learning System Outcome-Based EducationTrinidad, Gwen StefaniNo ratings yet

- Selection Guide OboDocument40 pagesSelection Guide ObovjtheeeNo ratings yet

- Berkeley Multimedia WorkshopDocument7 pagesBerkeley Multimedia WorkshopVisual EditorsNo ratings yet

- Moto 14G-16GDocument21 pagesMoto 14G-16GRafael RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Top 40 Indian companies by security codeDocument264 pagesTop 40 Indian companies by security codeMNV MuraliNo ratings yet

- Catalogue - Single - Three - Phase LAFERTDocument101 pagesCatalogue - Single - Three - Phase LAFERTAleex RodriguezNo ratings yet

- S7B - Passive Voice Modal VerbsDocument4 pagesS7B - Passive Voice Modal VerbsDavid GuzmanNo ratings yet

- AU Price List 01 Jul 2021Document40 pagesAU Price List 01 Jul 2021Kushal DixitNo ratings yet

- Marksheet Unit 21Document2 pagesMarksheet Unit 21largeramaNo ratings yet

- Commerzbank Tower Merupakan Sebuah Pencakar Langit Yang Terletak Di FrankfurtDocument6 pagesCommerzbank Tower Merupakan Sebuah Pencakar Langit Yang Terletak Di FrankfurtHandikaNo ratings yet

- Diabetic Diagnose Test Based On PPG Signal andDocument5 pagesDiabetic Diagnose Test Based On PPG Signal andAl InalNo ratings yet

- CUSAT Electronics Thesis on Compact Asym Coplanar AntennasDocument230 pagesCUSAT Electronics Thesis on Compact Asym Coplanar AntennasdhruvaaaaaNo ratings yet

- Att. 2. POF - Specs - 2009-M (Part of Scope of Work P23) PDFDocument38 pagesAtt. 2. POF - Specs - 2009-M (Part of Scope of Work P23) PDFChristian Olascoaga MoriNo ratings yet

- Ariel Corporation - Arielcorp - Com11Document1 pageAriel Corporation - Arielcorp - Com11Anwar SadatNo ratings yet

- BO Web Intelligence XI Report Design QA210 Learner's GuideDocument374 pagesBO Web Intelligence XI Report Design QA210 Learner's GuideTannoy78No ratings yet

- Northridge Farms Site PlansDocument43 pagesNorthridge Farms Site PlansChristian SmithNo ratings yet

- Lec 4 - Aerated Lagoons & Secondary Clarifier (Compatibility Mode)Document7 pagesLec 4 - Aerated Lagoons & Secondary Clarifier (Compatibility Mode)Muhammad FarhanNo ratings yet

- Manual JVC KW-XC828 PDFDocument94 pagesManual JVC KW-XC828 PDFMassolo RoyNo ratings yet

- Compositional Analysis by ThermogravimetryDocument3 pagesCompositional Analysis by ThermogravimetryAngelita Cáceres100% (2)

- Operation of A Typical,: Batch-Homogenizing SystemDocument2 pagesOperation of A Typical,: Batch-Homogenizing SystemKwameOpareNo ratings yet

- Exodus 4W Instruction ManualDocument2 pagesExodus 4W Instruction ManualgjbishopgmailNo ratings yet

- Half Wave Rectifier ExplainedDocument13 pagesHalf Wave Rectifier ExplainedAmey Pashte91% (11)

- Honda Scv100cm Scv110 SparesDocument144 pagesHonda Scv100cm Scv110 Sparesmaniamson92% (12)