Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Oliver Antonia Sobre Anzaldua en Spain

Uploaded by

lucysombraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Oliver Antonia Sobre Anzaldua en Spain

Uploaded by

lucysombraCopyright:

Available Formats

Gloria Anzaldas Borderless Theory in Spain

Author(s): Maria Antnia Oliver-Rotger

Source: Signs, Vol. 37, No. 1 (Autumn 2011), pp. 5-10

Published by: The University of Chicago Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/660169 .

Accessed: 05/11/2014 05:18

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Signs.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 84.88.84.116 on Wed, 5 Nov 2014 05:18:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S I G N S

Autumn 2011

por otra: Testimonios de Latin@s in the U.S. through Cyberspace (11 de septiembre

de 200111 de marzo de 2002), ed. Claire Joysmith and Clara Lomas, 92103.

Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autonoma de Mexico.

Gloria Anzalduas Borderless Theory in Spain

Maria Anto`nia Oliver-Rotger

ince the mid-1990s, Gloria Anzaldu

as work, and in particular Borderlands/La Frontera (1987), has become very significant to Spanish

scholarship concerned with the critique of Western modernity and its

aftermaths. The first scholars to be influenced by the decolonial, deconstructivist impulses in her thinking were those who, from their respective filologia

anglesa (English philology) departments, conducted research on American

studies, gender studies, and cultural studies, as well as postcolonial, African

American, and Chicano/a studies. However, Anzaldua has also had a particular bearing on the fields of Spanish language and literature (filologia hispanica), translation, philosophy, art, and immigration studies, which confirms

the disciplinary permeability of a theory that knows no borders.

One of the first widely circulated Spanish texts to acknowledge Anzalduas contribution to feminist theory was the volume edited by Marta

` ngels Carab, Feminismo y crtica literaria (2000). Anzaldua

Segarra and A

is aligned here with thinkers like Chandra Talpade Mohanty and Gayatri

Chakravorty Spivak, who have questioned the Eurocentrism of feminist

thought prevalent until the early 1980s. Anzalduas contribution to feminism is seen as replacing the Western feminist subject with one who

understands herself relationally, although not uncritically so, with respect

to the family, the community, and the figure of the mother. In a more

extensive analysis of Anzalduas writing, my essay Sangre Fertil/Fertile

Blood: War, Migratory Crossings and Healing in Borderlands/La Frontera (Oliver-Rotger 2001) views Anzalduas Borderlands/La Frontera as

a hybrid text whose multiple discourses (critical mythopoesis, poetry, historical revision, feminist and postnationalist critiques of identity and culture) converge to recount and heal the wounds inflicted on both the female

writing subject and the multiple collectivities she speaks for and against.

With regard to Anzalduas contribution to theories of sexuality, the

philosopher and art critic Beatriz Preciado has written about Anzalduas

[Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2011, vol. 37, no. 1]

2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0097-9740/2011/3701-0002$10.00

This content downloaded from 84.88.84.116 on Wed, 5 Nov 2014 05:18:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Symposium: Gloria E. Anzaldua, an International Perspective

ideas for a Spanish readership in academic venues, as well as in the Spanish

press (Preciado 2004, 2007). As a Spanish speaker and a specialist in queer

theory heavily influenced by Judith Butler, Preciado has found in Anzaldua

and Cherre Moraga her privileged interlocutors. In her essay Multitudes

queer: Notas para una poltica de los anormales (Queer multitudes: Notes

toward a politics of abnormality) she speaks of Anzaldua as belonging to

post-feminist queer multitudes in the sense that, without wanting to

do away with feminism, these multitudes engage in a reflective confrontation of feminism (Preciado 2004) and challenge it for erasing differences in order to develop a hegemonic, heterocentric political subject

(Preciado 2004). Along these lines, in Teora encarnada y pensamiento

fronterizo (2008) I examined Anzaldua and Moragas nonessentialist

lesbianism as a condition of marginality that develops into a critical hermeneutic tool for challenging what Emma Perez calls the colonial imaginary (1999, 6) of Mexican/Chicano culture and what Walter Mignolo

terms colonial subalternity (2001, 30) in the wider context of the Americas (Oliver-Rotger 2008).

Also grounded in decolonial thought, Indias y fronteras: El discurso en

torno a la mujer etnica by Silvia Martnez-Falquina (2004) engages in an

interesting comparative study of the liberatory possibilities of post-indianista thought in the works of such writers as Anzaldua, Paula Gunn

Allen, Louise Erdrich, and Diane Glancy (Martnez-Falquina 2004, 7).

Martnez-Falquina contends that it is not always the case that these writers

successfully overcome the notion of precolonial Native Americans as pure

and somehow precultural, which characterizes colonial indianista discourse. Another Spanish scholar, Nieves Pascual Soler (2000), offers an

insightful analysis of this assumption of a stage prior to fusion or mestizaje

in her contribution to New Exoticisms: Changing Patterns in the Construction of Otherness (Santaolalla 2000). For Pascual Soler, Anzalduas

new exoticism takes advantage of the commodification of otherness to

construct new identities, recover a tradition, and do away with stereotypes.

Spanish scholars in the field of translation and linguistics have analyzed

the ways in which Anzalduas linguistic hybridization is essential for the

construction and expression of a deterritorialized identity. In Espais de

frontera Pilar Godayol (2000), a translator of Chicana literature into Catalan, considers Anzalduas disarticulation of the assumed place of the

masculine imperial speaking subject to be a necessary position for the task

of translation, which she understands not so much as the carrying over

of meaning from one language to another but as mediation and constant

negotiation between several systems of reference. In Asymetries in/of

frica Vidal ClaTranslation (2004) Rosario Martn Ruano and Carmen A

ramonte, specialists in translation theory, look at Anzalduas Borderlands

This content downloaded from 84.88.84.116 on Wed, 5 Nov 2014 05:18:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S I G N S

Autumn 2011

as a plurilingual text that travels between cultures and makes the familiar

strange for the dominant culture without forsaking the authors marginality vis-a`-vis dominant cultures. Similarly, Antonio Torres (2009) sees

Anzalduas open, unrestricted use of varieties of Chicano Spanglish as a

challenge to the linguistic colonization effected by the Spanish languages

ethnocentric territorialization.

Anzalduas critique of the Western feminist, nationalist, heteronormative

subject was one of the theoretical strategies informing the art exhibit Fugas

subversivas (Subversive escapes), curated by Guillermo Cano, Ran Lozano,

and Johanna Moreno in 2005 at the University of Valencia.1 They brought

together more than fifteen Spanish artists and groups that denounce the

imposition of sexual, gender, and linguistic identities in contemporary society.

As in the United States, in Spain Borderlands/La Frontera has been

acknowledged as a foundational text in literary and cultural studies for

theorizing notions of the border or frontera to be crossed as opposed to

the American frontier to be conquered. The volume edited by Jesus Benito

and Ana Mara Manzanas, Literature and Ethnicity in the Cultural Borderlands (2002), contests grand narratives and proposes alternative ones

that defy national histories while extricating the paradigm of the borderlands from its application solely to the cultural predicament of Mexican

Americans. As an example, migration between Spain and Africa, and the

seasonal shrinking or widening of the borderlands between them, serves

as a useful counterpart to the U.S.-Mexico border, given that both borders

function as demarcating lines between the third and first worlds, the colonizer and the colonized.

While the field of geography in Spain has yet to take Anzalduas work

into account in terms of her understanding of space, for Spanish scholars

in the field of literary and cultural studies Anzalduas narration of the

impact of social and material space on the constitution of the gendered

subject has been inspirational. In my own Battlegrounds and Crossroads:

Social and Imaginary Space in Writings by Chicanas (Oliver-Rotger 2003)

nand in Manuel Albadalejo Martnezs Hacia una cartografa de Los A

geles a traves de la literatura chicana (2007), Anzalduas concept of

borderlands is a paradigm enabling inquiry into the relationship between

intimate and public spaces in Chicana/o literature. The cross-pollination

between the methodologies of literary criticism and cultural geography is

also outstanding in Manzanas Calvos Contested Passages: Migrants

Crossing the Ro Grande and the Mediterranean Sea (2006) as well as

in most of the essays of her edited volume Border Transits (2007). Though

1

See the exhibit Web site at http://www.uv.es/cultura/c/docs/expfuguessubversivescast.htm.

See also Piqueras-Sanchez (2005).

This content downloaded from 84.88.84.116 on Wed, 5 Nov 2014 05:18:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Symposium: Gloria E. Anzaldua, an International Perspective

not always acknowledged, Anzalduas notion of the borderlands has undoubtedly inspired Manzanass work, as well as the essays by Manuel MartnRodrguez (2007), Javier Duran (2007), and Jose Pablo Villalobos (2007)

in Border Transits, which engage in transnational comparative studies of

writers who, like Anzaldua herself, inhabit transitory literary and geographical spaces.

To end this brief review, I should say that perhaps the most neglected

aspect of Anzalduas theory in Spain is her contribution to global or transnational feminism, especially insofar as it may apply to issues of immigration

and gender. In 2004, the anthology Otras inapropiables, an initiative from

the grassroots feminist collective Eskalera Karakola (Spiral staircase) based

in the multiethnic neighborhood of Lavapies, Madrid, published a Spanish

translation of outstanding texts by authors Anzaldua, Aurora Levins Morales, bell hooks, Avtar Brah, and Chela Sandoval (Eskalera Karakola

2004). Registered with Creative Commons, the volume breaches the constraints that copyright laws place on the accessibility of academic texts and

makes available feminist texts that insist on the intersection of gender,

migration, and the global political economy. The introduction to this

volume contextualizes the essays within a necessary but not yet accomplished refashioning of Spanish feminist discourses and practices: While

Spanish feminism was prompted by class struggle and the critique of Francisco Francos national-Catholic idea of Spain, todays white Spanish

feminism reacts with ambivalence to issues such as the changing racial and

cultural demographics generated by migrations from Africa and Latin

America, the fortification of Spanish borders, the often cynical approaches

that the mass media and the political class bring to the feminization of

poverty and the vulnerability of migrant women, and the role of the mass

media in perpetuating stereotypes and menacing views of the other. In

order to do away with cultural relativism, localism, and stereotypes, Otras

inapropiables calls for the transnational coalitions that Anzalduas borderless

theory encourages feminist collectives to establish.

Department of Humanities

Universitat Pompeu Fabra

References

ngeles a traves

Albadalejo Martnez, Manuel. 2007. Hacia una cartografa de Los A

de la literatura chicana [Toward a cartography of Los Angeles through Chicano

literature]. PhD dissertation, Alicante University.

Anzaldua, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. San Francisco:

Spinsters/Aunt Lute.

This content downloaded from 84.88.84.116 on Wed, 5 Nov 2014 05:18:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

S I G N S

Autumn 2011

Benito, Jesus, and Ana Maria Manzanas, eds. 2002. Literature and Ethnicity in

the Cultural Borderlands. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Duran, Javier. 2007. Border Voices: Life Writings and Self-Representation of the

U.S.-Mexico Frontera. In Manzanas 2007, 6178.

Eskalera Karakola, ed. 2004. Otras inapropiables: Feminismos desde las fronteras

[Inappropriable others: Feminisms from the borderlands]. Trans. Maria Serrano

lvaro

Gimenez, Rocio Macho Ronco, Hugo Romero Fernandez Sancho, and A

Salcedo Rufo. Madrid: Traficantes de Suen

os. http://www.nodo50.org/ts/

editorial/otrasinapropiables.pdf.

Godayol, Pilar. 2000. Espais de frontera: Ge`nere i traduccio [Border spaces: Gender

and translation]. Barcelona: Eumo.

Manzanas, Ana Maria, ed. 2007. Border Transits: Literature and Culture across

the Line. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Manzanas Calvo, Ana Maria. 2006. Contested Passages: Migrants Crossing the

Ro Grande and the Mediterranean Sea. South Atlantic Quarterly 105(4):

75975.

Martn-Rodrguez, Manuel. 2007. Mapping the Trans/Hispanic Atlantic: Nuyol,

Miami, Tenerife, Tangier. In Manzanas 2007, 20522.

frica Vidal Claramonte. 2004. Asymmetries

Martn Ruano, Rosario, and Carmen A

in/of Translation: Translating Translated Hispanicism(s). TTR: Traduction,

terminologie, redaction 17(1):81105.

Martnez-Falquina, Silvia. 2004. Indias y fronteras: El discurso en torno a la mujer

etnica [Indian women and the border: The ethnic womans discourse]. Oviedo:

KRK.

Mignolo, Walter. 2001. Coloniality at Large: The Western Hemisphere in the

Colonial Horizon of Modernity. Trans. Michael Ennis. CR: The New Centennial Review 1(2):1954.

Oliver-Rotger, Maria Anto`nia. 2001. Sangre Fertil/Fertile Blood: Migratory

Crossings, War and Healing in Gloria Anzalduas Borderlands /La Frontera.

In Dressing Up for War: Transformations of Gender and Genre in the Discourse

and Literature of War, ed. Aranzazu Usandizaga and Andrew Monnickendam,

189211. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

. 2003. Battlegrounds and Crossroads: Social and Imaginary Space in Writings by Chicanas. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

. 2008. Teora encarnada y pensamiento fronterizo en las autobiografas

de Gloria Anzaldua y Cherre Moraga [Embodied theory and border thinking

in the autobiographies of Gloria Anzaldua and Cherre Moraga]. In Que sus

faldas son ciclones: Representacion literaria contemporania del lesbianismo en

lengua inglesa [Her skirts are cyclones: Contemporary literary representation

of lesbianism in English], ed. Rosa Garca Rayego and Mara Soledad Sanchez

Gomez, 16784. Madrid: Egales.

Pascual Soler, Nieves. 2000. Autobiographies in La Frontera: Gloria Anzaldua.

In Santaolalla 2000, 24150

Perez, Emma. 1999. The Decolonial Imaginary: Writing Chicanas into History.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

This content downloaded from 84.88.84.116 on Wed, 5 Nov 2014 05:18:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

10

Symposium: Gloria E. Anzaldua, an International Perspective

Piqueras-Sanchez, Norberto, ed. 2005. Fugas subversivas: Reflexiones hbridas sobre

la(s) identidad(es) [Subversive escapes: Hybrid reflections on identities]. Exhibition catalog. Valencia: Universitat de Valencia, Servei de Publicacions.

Preciado, Beatriz. 2004. Multitudes queer: Notas para una poltica de los anormales [Queer multitudes: Notes toward a politics of abnormality]. Multitudes 12 (suppl.), http://multitudes.samizdat.net/Multitudes-queer,1465.

. 2007. Despues del feminismo: Mujeres en los margenes [After feminism:

Women in the margins]. El Pas, January 13, 23.

Santaolalla, Isabel, ed. 2000. New Exoticisms: Changing Patterns in the Construction of Otherness. Amsterdam: Rodopi.

` ngels Carab, eds. 2000. Feminismo y crtica literaria [FemSegarra, Marta, and A

inism and literary criticism]. Barcelona: Icaria.

Torres, Antonio. 2009. Expresion lingustica e identidad en los latinos de los

Estados Unidos [Latino language and identity in the United States]. Confluenze 1(2):81100.

Villalobos, Jose Pablo. 2007. Up against the Border: A Literary Response. In

Manzanas 2007, 3552.

Medi-terranean Borderization

Paola Zaccaria

as a result of the diasporas produced by new

wars and new forms of colonialism, boats, rubber dinghies, and wornout ships started sailing in the direction opposite to that of colonial

times: people emigrating from North Africa steered toward the closest

Mediterranean shores, especially to the Italian island of Lampedusa, the

t the end of the 1990s,

In breaking the word Mediterraneanwhich means sea in the middle of the earth,

from the Latin medius (middle) terra (land, earth)with a hyphen, as Medi-terranean,

I want to point out that many European and Eastern names for this sea stress the fact that it

is a sea between lands/earths/continents (Europe, Africa, and Asia). The Medi-terrannean is

the water that licks/laps the lands of three continents; it is a water route that has created and

still creates cultural intercourseeven through wars and colonialismbetween different populations, economies, ideas, and discourses. Because the Mediterranean flows in the middle of

so many lands and belongs to many countries, I consider European policies of refoulement

of people coming from the other two continents to be a methodology of oppression, a virtual

building of walls, which has devastating effects on the lives of socially disadvantaged Mediterranean people.

[Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 2011, vol. 37, no. 1]

2011 by The University of Chicago. All rights reserved. 0097-9740/2011/3701-0003$10.00

This content downloaded from 84.88.84.116 on Wed, 5 Nov 2014 05:18:28 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Decomposer Poster 1Document3 pagesDecomposer Poster 1api-535379067No ratings yet

- FurtherDocument10 pagesFurtherDuda DesrosiersNo ratings yet

- Learning Good ConsentDocument24 pagesLearning Good ConsentcutpasteeducationNo ratings yet

- Porn After Porn Intro-Contents-libreDocument20 pagesPorn After Porn Intro-Contents-librelucysombraNo ratings yet

- Toward The Queerest InsurrectionDocument8 pagesToward The Queerest InsurrectionlucysombraNo ratings yet

- Vance - Carole S. (Ed.) - Pleasure and Danger - Exploring Female SexualityDocument464 pagesVance - Carole S. (Ed.) - Pleasure and Danger - Exploring Female Sexualitylucysombra88% (8)

- Moser Law 2003 Making VoicesDocument24 pagesMoser Law 2003 Making VoiceslucysombraNo ratings yet

- Slavoj Zizek No Sex PleaseDocument10 pagesSlavoj Zizek No Sex PleaselucysombraNo ratings yet

- What Is Queer Technology?Document12 pagesWhat Is Queer Technology?lucysombraNo ratings yet

- MinipimerTV HERE, THERE AND (Above All) NOWDocument4 pagesMinipimerTV HERE, THERE AND (Above All) NOWlucysombraNo ratings yet

- Procurement QC SupervisorDocument2 pagesProcurement QC SupervisorAbdul Maroof100% (1)

- 0610 w17 Ms 23 PDFDocument3 pages0610 w17 Ms 23 PDFBara' HammadehNo ratings yet

- Metab II DiverticulosisDocument94 pagesMetab II DiverticulosisEthel Lourdes Cornejo AmodiaNo ratings yet

- Journal Reading PsikiatriDocument8 pagesJournal Reading PsikiatriNadia Gina AnggrainiNo ratings yet

- Ial A2 Oct 22 QPDocument56 pagesIal A2 Oct 22 QPFarbeen MirzaNo ratings yet

- Class 4 National Genius Search Examination: Advanced: Check The Correctness of The Roll No. With The Answer SheetDocument3 pagesClass 4 National Genius Search Examination: Advanced: Check The Correctness of The Roll No. With The Answer SheetPPNo ratings yet

- The Rise of The English Novel: (LITERARY CRITICISM (1400-1800) )Document2 pagesThe Rise of The English Novel: (LITERARY CRITICISM (1400-1800) )Shivraj GodaraNo ratings yet

- The Use of Technological Devices in EducationDocument4 pagesThe Use of Technological Devices in EducationYasmeen RedzaNo ratings yet

- Customer Service Manager ResumeDocument2 pagesCustomer Service Manager ResumerkriyasNo ratings yet

- School ViolenceDocument10 pagesSchool ViolenceCường Nguyễn QuốcNo ratings yet

- Civic EducationDocument35 pagesCivic EducationMJAY GRAPHICSNo ratings yet

- Icke - Frank Ankersmit's Narrative Substance A Legacy To Historians (Rethinking History)Document19 pagesIcke - Frank Ankersmit's Narrative Substance A Legacy To Historians (Rethinking History)Alfonso_RoqueNo ratings yet

- Presentation and Viva Voice QuestionsDocument4 pagesPresentation and Viva Voice QuestionsMehak Malik100% (2)

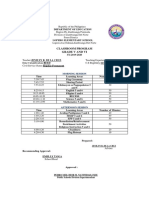

- Classroom Program JenDocument1 pageClassroom Program JenjenilynNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - Clasa A 3-ADocument3 pagesLesson Plan - Clasa A 3-AMihaela Constantina VatavuNo ratings yet

- Modelo Salud Mental Positiva LluchDocument15 pagesModelo Salud Mental Positiva LluchYENNY PAOLA PARADA RUIZ100% (1)

- C.V. Judeline RodriguesDocument2 pagesC.V. Judeline Rodriguesgarima kathuriaNo ratings yet

- Tagore and IqbalDocument18 pagesTagore and IqbalShahruk KhanNo ratings yet

- Non-Family Employees in Small Family Business SuccDocument19 pagesNon-Family Employees in Small Family Business Succemanuelen14No ratings yet

- IceDocument3 pagesIceJaniNo ratings yet

- Practice 2: Vocabulary I. Complete The Sentences With The Correct Form of The Words in CapitalsDocument4 pagesPractice 2: Vocabulary I. Complete The Sentences With The Correct Form of The Words in CapitalsLighthouseNo ratings yet

- Nurs 479 Professional Development PowerpointDocument10 pagesNurs 479 Professional Development Powerpointapi-666410761No ratings yet

- BCA - 4 Sem - Ranklist - May - June 2011Document30 pagesBCA - 4 Sem - Ranklist - May - June 2011Pulkit GosainNo ratings yet

- Brain VisaDocument31 pagesBrain VisaKumar NikhilNo ratings yet

- CM 9Document10 pagesCM 9Nelaner BantilingNo ratings yet

- Theories of ChangeDocument6 pagesTheories of ChangeADB Knowledge SolutionsNo ratings yet

- Kindergarten q2 Week1 v2Document30 pagesKindergarten q2 Week1 v2ALEJANDRO SORIANONo ratings yet

- What Is Referencing - Reference List Entry v1Document3 pagesWhat Is Referencing - Reference List Entry v1Abdulwhhab Al-ShehriNo ratings yet