Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri V Daya Lea

Uploaded by

chunlun87Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri V Daya Lea

Uploaded by

chunlun87Copyright:

Available Formats

1

Malayan Law Journal Reports/2005/Volume 4/KETUA PENGARAH HASIL DALAM NEGERI v DAYA

LEASING SDN BHD - [2005] 4 MLJ 138 - 29 January 2005

14 pages

[2005] 4 MLJ 138

KETUA PENGARAH HASIL DALAM NEGERI v DAYA LEASING SDN BHD

COURT OF APPEAL (PUTRAJAYA)

MOKHTAR SIDIN, AUGUSTINE PAUL JJCA AND AZMEL J

CIVIL APPEAL NO W-01-11 OF 2000

29 January 2005

Revenue Law -- Income tax -- Company taxation -- Common expenses -- Method of apportioning common

expenses between leasing and non-leasing business -- Income Tax Act 1967 s 33(1) & Income Tax Leasing

Regulations 1986

Revenue Law -- Income tax -- Common expenses -- Method of apportioning common expenses between

leasing and non-leasing business -- Income Tax Act 1967 s 33(1) & Income Tax Leasing Regulations 1986

The respondent was principally engaged in the provision of leasing, factoring and hire purchase financing

facilities. There were expenses and interest payments on loans from the respondent's holding company

common to both the leasing and non-leasing businesses which required apportionment between the two

sources. The respondent was unable to specifically attribute the exact amount of the common expenses to

the respective leasing and non-leasing business. This led to the dispute between the parties. The issue for

determination was the ascertainment of the correct method of apportioning the common expenses incurred

by the respondent in its leasing and non-leasing business. The Special Commissioners of Income Tax upheld

the method adopted by the appellant in apportioning the common expenses which did not find favour with the

High Court.

In calculating the common expenses and interest attributed to the leasing and non-leasing businesses

respectively, the respondent's formula ignored the capital element in the lease rentals while the appellant's

formula included the entire lease rentals, ie both the interest and capital elements. The critical matter for

consideration was the finding of the learned trial judge that the element of principal should not be taken into

account for the apportionment of the common expenses in lease financing as there was no provision in the

Income Tax Act 1967 ('the Act') or in the Income Tax Leasing Regulations 1986 ('the 1986 Regulations')

prescribing the manner of doing so in respect of different income sources.

Held, allowing the appeal with costs:

1)

1)

The meaning of 'gross income' in s 33(1) of the Act must be construed in the light of regs 2 and

3 of the 1986 Regulations. The result is that in the case of a leasing business the gross income

of a person shall be the principal and interest as a separate source for the purpose of

ascertaining his adjusted income under s 33(1) of the Act. Thus the contention of

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 139

the respondent that the gross income must be confined to the interest element of the leasing

business was wholly unsustainable in law (see para 20).

Section 33(1) of the Act which must be read with s 5(c) of the Act is applicable even in cases

where a person has more than one source of income. If a person has two or more sources of

income then his adjusted income must, as provided by s 33(1) of the Act, be ascertained

separately source by source (see para 21). In order to ensure that s 33(1)of the Act is not

rendered otiose the power of the appellant to apportion common expenses must be construed

1)

as being implied and therefore an integral part of the section; a construction that will be

consistent with its object and purpose (see para 23).

The respondent's gross income for the leasing business shall constitute the principal and

interest elements for the purpose of ascertaining its adjusted income as provided by law. The

exclusion of the principal element in the apportionment exercise in this case would be a clear

violation of s 33(1) of the Act read with reg 3 of the 1986 Regulations. The common expenses

incurred must be apportioned pursuant to s 33(1) of the Act. The method of apportionment

followed by the appellant was therefore in compliance with the law (see para 24).

[Bahasa Malaysia summary

Responden terlibat sepenuhnya dalam menyediakan perkhidmatan sewa beli, perkilangan dan kemudahan

pembiayaan sewa beli. Terdapat perbelanjaan dan bayaran faedah untuk pinjaman daripada syarikat

pelaburan induknya, responden yang melibatkan kedua-dua perniagaan sewa beli dan bukan sewa beli,

iaitu, perbelanjaan bersesama yang menghendaki pembahagian antara dua sumber. Responden tidak dapat

memberikan jumlah tepat perbelanjaan bersesama berkaitan perniagaan sewa beli dan bukan sewa beli. Ini

mengakibatkan berlakunya pertikaian antara pihak-pihak. Persoalan untuk ditentukan adalah menetapkan

cara betul dalam membahagikan perbelanjaan bersesama yang ditanggung oleh responden dalam

perniagaan sewa beli dan bukan sewa belinya. Pesuruhjaya Khas Cukai Pendapatan bersetuju dengan cara

yang digunakan oleh perayu dalam pembahagian perbelanjaan biasa yang tidak disetujui oleh Mahkamah

Tinggi.

Dalam mengira perbelanjaan bersesama dan faedah yang disebabkan oleh perniagaan sewa beli dan bukan

sewa beli masing-masingnya, formula responden tidak mengira elemen kapital dalam sewaan sewa beli

manakala formula perayu termasuklah keseluruhan sewaan sewa beli itu, iaitu kedua-dua elemen faedah

dan kapital. Perkara kritikal untuk dipertimbangkan adalah penemuan hakim perbicaraan yang bijaksana

bahawa elemen prinsipal tidak patut diambil kira dalam pembahagian perbelanjaan bersesama dalam

kemudahan sewa beli kerana tiada peruntukan dalam Akta Cukai Pendapatan 1967 ('Akta tersebut') atau

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 140

dalam Peraturan-Peraturan Cukai Pendapatan (Pajakan) 1986 ('Peraturan 1986') yang menyatakan cara

berbuat demikian berkaitan sumber pendapatan yang berbeza.

Diputuskan, membenarkan rayuan dengan kos:

2)

2)

2)

Maksud 'gross income' dalam s 33(1) Akta tersebut hendaklah ditafsirkan berdasarkan per 2

dan 3 Peraturan 1986. Akibatnya dalam kes berkaitan perniagaan sewa beli, pendapatan kasar

seseorang hendaklah merupakan prinsipal dan faedah sebagai satu sumber berasingan bagi

tujuan menentukan pendapatan beliau yang disesuaikan di bawah pendapatan terlaras s 33(1)

Akta tersebut. Oleh itu, hujah responden bahawa pendapatan kasar beliau terbatas kepada

elemen faedah perniagaan pajakan tidak boleh dikekalkan di sisi undang-undang (lihat

perenggan 20).

Seksyen 33(1) Akta tersebut yang perlu dibaca bersama s 5(c) Akta tersebut adalah terpakai

dalam kes-kes di mana seseorang itu mempunyai lebih daripada satu sumber pendapatan. Jika

seseorang itu mempunyai dua atau lebih sumber pendapatan maka pendapatan yang terlaras

adalah, seperti yang diperuntukkan oleh s 33(1) Akta tersebut, ditentukan secara berasingan

mengikut sumber (lihat perenggan 21). Bagi tujuan memastikan bahawa s 33(1) Akta tersebut

tidak dianggap otiose kuasa perayu untuk membahagikan perbelanjaan biasa tersebut

hendaklah ditafsirkan sebagai tersirat dan oleh itu bahagian integral seksyen tersebut; satu

tafsiran yang konsisten dengan objektif dan tujuannya (lihat perenggan 23).

Pendapatan kasar responden untuk perniagaan pajakan hendaklah membentuk elemenelemen prinsipal dan faedah bagi tujuan menentukan pendapatannya yang disesuaikan seperti

yang diperuntukkan oleh undang- undang. Pengecualian elemen prinsipal dalam pelaksanaan

pembahagian dalam kes ini adalah perlanggaran nyata s 33(1) Akta tersebut dibaca bersama

peraturan 3 Peraturan 1986. Perbelanjaan biasa yang ditanggung hendaklah dibahagikan

menurut s 33(1) Akta tersebut. Cara pembahagian yang diikuti oleh perayu oleh itu mematuhi

undang-undang (lihat perenggan 24).]

Notes

For cases on company taxation, see 10 Mallal's Digest (4th Ed, 2002 Reissue) paras 2146-2149.

For cases on income tax generally, see 10 Mallal's Digest (4th Ed, 2002 Reissue) paras 2005-2331.

Cases referred to

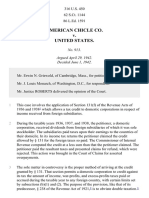

Cape Brandy Syndicate v IRC [1921] 1 KB 64 (refd)

Dato Mohamed Hashim Shamsuddin v Attorney General, Hong Kong [1986] 2 MLJ 112 (refd)

Ostime (Inspector of Taxes) v Duple Motors Bodies Ltd

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 141

[1961] All ER 167 (refd)

Legislation referred to

Income Tax Act 1967

ss 5, 24(5)(a), 33(1),

36

Income Tax Leasing Regulations 1986 reg 3

Appeal from

Tax Appeal No R1-14-7 of 1997 (High Court, Kuala Lumpur)

Abu Tariq Jamaluddin (Hazlina bte Hussain with him) (Legal Officer, Lembaga Hasil Dalam Negeri) for the

appellant.

Tay Hong Huat (Tay & Helen Wong) for the respondent.

Augustine Paul JCA

(delivering judgment of the court)

1 The issue for determination in this appeal before us is the ascertainment of the correct method of

apportioning the common expenses incurred by the respondent (the appellant in the court below) in its

leasing and non-leasing business. The Special Commissioners of Income Tax upheld the method adopted by

the appellant (the respondent in the court below) in apportioning the common expenses which did not find

favour with the High Court.

2 The facts of the case may be set out as follows. The respondent is principally engaged in the provision of

leasing, factoring and hire purchase financing facilities. There are expenses and interest payments on loans

from the respondent's holding company common to both the leasing and non-leasing businesses which

require apportionment between the two sources. The respondent was unable to specifically attribute the

exact amount of the common expenses to the respective leasing and non-leasing business. This led to the

dispute between the parties.

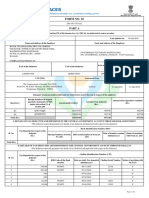

3 The respondent's income from the leasing and non-leasing businesses and common expenses as shown in

their accounts for the relevant years are as follows:

(a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

Year of Assessment Sum total of lease

Income from leasing Income from nonSum total of the

rentals received and portfolio

leasing portfolio

Comon Expenses

receivable for years of

income from leasing

operations excluding

profit from sale of

leased assets

5,002,252

5,076,098

2,747,701

2,514,209

3,074,336

4,165,240

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1,323,083

670,943

645,147

673,681

780,995

805,815

833,204

1,161,972

847,166

639,467

487,234

508,712

732,702

1,084,670

958,880

769,299

811,285

960,371

4

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 142

The table below sets out figures showing the lease rentals comprising the principal and interest elements

which together with incidental income make up the gross income from the leasing business and also the

gross income from the non-leasing business and the common expenses.

LEASING PORTFOLIO

NON-LEASING PORTFOLIO

COMMON EXPENSES

Leasing RentalsPrincipal + Interest = Gross Income*

A

B

C

D

(RM)

(RM)

(RM)

(RM)

(RM)

1987

3,679,169

1,158,622

5,000,252

833,204

732,702

1988

4,405,155

553,441

5,076,098

1,161,972

1,084,670

1989

2,102,554

619,548

2,747,701

847,166

958,880

1990

1,840,528

637,086

2,514,209

639,467

769,299

1991

2,293,341

753,730

3,074,336

487,234

811,285

1992

3,359,425

777,316

4,165,240

508,712

960,371

* including incidental income

5 The following figures which appear from the profit and loss accounts of the respondent are the interest

element of the rentals receivable for the leasing business in the respective years of assessment:

Year of Assessment

Interest Income (RM)

1987

1,158,622

1988

553,441

1989

619,548

1990

637,086

1991

753,730

1992

777,316

6 The common expenses and interest attributed to the leasing and non- leasing businesses respectively are

derived in accordance with the following formula:

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 143

Leasing portfolio

X

X+Y

X

X+Y

Non-leasing portfolio

NL

=

Where:

L is the apportioned expenses for the leasing business.

NL is the apportioned expenses for the non-leasing business.

X is disputed and forms the subject matter of this appeal. For the

respondent, X represents the figures shown in (b) in the account

reproduced earlier. For the appellant, X represents the figures

shown in column (a) of the accounts.

Y represents the figures shown in column (c) of the accounts.

Z represents the figures shown in column (d) of the accounts.

7 The appellant's method was used to apportion the common expenses for the purpose of determining the

adjusted income from the leasing and on- leasing business. The gross income from the leasing business

comprised principal plus interest and incidental income while the gross income from the non-leasing portfolio

comprised only interest and incidental income. In short, the respondent's formula ignores the capital element

in the lease rentals while the appellant's formula includes the entire lease rentals, ie both the interest and

capital elements. The taxes payable by the respondent as assessed for the years of assessment 1987 to

1992 are as follows:

Year of assessment

Date of assessment

Form

Tax assessed payable

(RM)

1987

30 June 1993

JA

96,870.60

1988

30 June 1993

JA

243,415.35

1989

30 June 1993

J

77,158.40

1990

30 June 1993

J

130,202.28

1991

30 June 1993

J

86,330.68

1992

30 June 1993

J

156,014.94

8

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 144

The case for the respondent is that it is only the interest element that must be taken into account in respect

of gross income of the leasing business in line with the manner of ascertaining the gross income of the nonleasing business. The argument of the respondent is that the appellant's method will lead to a big proportion

of the expenses being attributable to the leasing business. It was argued that this is not in accordance with

the scheme of the law since there is no provision for apportioning the common expenses; it is not consistent

with the International Accounting Standard 17 which is fair and equitable; and that it is not in line with the

accounting practice where only the interest element of the leasing and non-leasing businesses are

considered as income. On the other hand the case for the appellant is that the income of leasing business

should constitute the principal and interest. The appellant contended that the method used by them is lawful

and that the question of it being unfair or unequitable is not a relevant matter for consideration. The Special

Commissioners of Income Tax were divided in their opinion and the majority upheld the method adopted by

the appellant.

9 The learned High Court judge ('the learned judge') who heard the appeal by the respondent considered the

majority judgment in detail and we can do no better than reproduce his summary of it. As he said, the

majority of the Special Commissioners first proceeded to examine what they termed general principles

regarding the law of taxation. They stated that the provisions of the Income Tax Act 1967 ('the Act') must be

strictly applied in the computation of profits or gains of persons chargeable to tax and that the general

scheme of the Act is that income tax is chargeable on the income earned in the relevant basis year. They

went on to examine s 5 of the Act which reads as follows:

5 Subject to this Act, the chargeable income of a person upon which tax is chargeable for a year of assessment shall

be ascertained in the following manner:

(a) first, the basis period for each of his sources for that year shall

be ascertained in accordance with Chapter 2 of Part III;

(b) next, his gross income from each source for the basis period for

that year shall be ascertained in accordance with Chapter 3 of that

Part;

(c) next, his adjusted income from each source (or, in the case of a

source consisting of a business, his adjusted income or adjusted

loss from the source) for the basis period for that year shall be

ascertained in accordance with Chapter 4 of that Part;

(d) next, his statutory income from each source of that year shall be

ascertained in accordance with Chapter 5 of that Part;

(e) next, his aggregate income for that year and his total income for

that year shall be ascertained in accordance with Chapter 6 of that

Part; and

(f) next, his chargeable income for that year shall be ascertained in

accordance with Chapter 7 of that Part ...

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 145

10 Their view was that it was clear from s 5 of the Act that the adjusted income from a business source (or

any other source) is gross income less all allowable deductions permitted by the Act. They next stated that

the deduction of expenses from gross income derived from a source is governed by the general provisions of

s 33(1) of the Act which reads as follows:

33(1) Subject to this Act, the adjusted income of a person from a source for the basis period for a year of assessment

shall be an amount ascertained by deducting from the gross income of that person from that source for that period all

outgoings and expenses wholly and exclusively incurred during that period by that person in the production of gross

income from that source, ...

11 They then observed that 'in order to arrive at adjusted income one has to deduct from the gross income all

outgoings and expenses wholly and exclusively incurred in the production of gross income' and 'emphasised'

that therefore the gross income is the one that matters. They then made an inference thus, 'since s 33(1)

talks about gross income it is only natural that the common expenses must be apportioned between the

leasing and the non-leasing portfolios using gross income'. They went on to say that to do otherwise would

be against the provisions of s 33(1)of the Act. Turning to the leasing portfolio, they pointed out that 'gross

income' is clearly defined in reg 3 of the Income Tax Leasing Regulations 1986 ('the 1986 Regulations')

which reads as follows:

3 Gross income of a lessor

The total sum of rentals of a lease term receivable in respect of a lease shall be deemed to accrue

evenly throughout the period of such lease term and the gross income of the lessor in respect of that

lease for the basis period for a year of assessment shall be a portion of the total sum receivable for

the lease term, being a portion which bears the same proportion to that total sum receivable as the

number of days in the basis period for that year assessment that falls within the lease term bears to

the total number of days of the lease term:

Provided that the full rentals receivable in the basis period for a year of assessment may be treated as the gross

income of the lessor for the basis period for that year of assessment where the Director General considers such

treatment to be just and reasonable in the circumstances.

12 They were of the view that from this it is clear that the 'gross income' of a leasing portfolio comprises of

the total rentals which is made up of principal plus interest and that on the other hand the gross income of a

non-leasing portfolio is only the interest as provided for under s 24(5)(a) of the Act which reads as follows:

(a) The interest shall be treated as gross income of the relevant person from the business for the relevant period if the

business is carried on at any time in the relevant period; and ...

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 146

13 They were of the view that, therefore, a different interpretation cannot be given for 'gross income' when

the law clearly provides what is gross income for leasing activities and that to do otherwise would be to

violate the law. They concluded that the respondent's method therefore has a legal basis, ie since s 33(1) of

the Act talks about 'gross income'. They noted that the 1986 Regulations were introduced later (the Act came

into force in 1967). They were of the view that the legislators must have had a basis for distinguishing the

income of leasing activities from the income of non-leasing activities. They observed that but for reg 3 of the

1986 Regulations, only the interest element would have constituted the gross income of leasing business

and in that respect, when capital allowance is given on the asset leased, it would appear that the cost of the

asset would be allowed twice. They were of the view that reg 3 of the 1986 Regulations was drafted with the

objective of rectifying this situation. They rejected the method of calculation used by the appellant on the

ground it has no legal basis and that it was advanced merely to serve the benefit of the appellant and in view

of what Lord Guest stated in Ostime (Inspector of Taxes) v Duple Motors Bodies Ltd [1961] All ER 167 that

the taxpayer cannot decide on what principle his income is to be assessed, the appellant's method cannot be

applicable.

14 The learned judge did not agree with the majority view of the Special Commissioners of Income Tax. He

first referred to s 36 of the Act which reads as follows:

36 Power to direct special treatment in the computation of business income in certain cases

(1) Notwithstanding any other provision of this Part, where the Director-General is satisfied that there

is a need for some special treatment in computing:

(a) the gross income from a business with respect to:

(i) a hire-purchase transaction;

(ii) a transaction under which a debt is payable by installments;

(iii) a lease transaction in respect of moveable property; or

(iv) any other transaction involving a debt or stock in trade; and

(b) the adjusted income from the business,

he may give directions and formulate regulations to be published in the Gazette for special treatment

with respect to any such transaction, either in relation to a particular business or in relation to any

business having any such transaction;

Provided that no such directions and regulations shall have effect in relation to a business for any year

of assessment with respect to which an assessment wholly or partly relating to income from that

business has become final and conclusive or is the subject of an appeal which has been sent forward

to the Special Commissioners.

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 147

(2) Any direction given under sub-s (1) with respect to the gross income and adjusted income from a

business or businesses may:

(a) provide that the gross income to which it relates (or any part thereof) shall be

taken to be gross income for such basis period or periods for such year or years of

assessment with respect to that business or those businesses as may be specified in

the direction;

(b) provide for special treatment with respect to the ascertainment of the adjusted

income from that business or those businesses for the basis period or periods for any

year or years of assessment.

15 In commenting on the directions given by the appellant under s 36of the Act and the consequences

thereof the learned judge said:

Section 36, it will be observed, makes clear reference to special treatment in computing both 'the gross income ... and

the adjusted income' because it is expected that any special treatment in computing the gross income has, perforce, to

provide for some special treatment in computing the adjusted income as well. In fact, it was pointed out by the minority

view that sub-s (2)(b) specifically empowers the respondent to provide for special treatment with respect to the

ascertainment of the adjusted income, envisaging the necessity for such special treatment to complement any special

treatment in computing the corresponding gross income. However, the 1986 Regulations, while requiring the gross

income from leasing transactions to be treated as being derived from a separate business source, did not at the same

time also provide for corresponding special treatment in ascertaining the adjusted income, particularly the manner of

apportioning common expenses to the leasing activity now that it is deemed a separate business source.

Thus there is neither a provision in the Act nor one in the 1986 Regulations (and it has not been shown there is a

provision in other Regulations) prescribing the manner for the apportionment of common expenses in respect of

different income sources. Quite clearly therefore there is no legal basis for the respondent to use his method to

apportion the common expenses in this case.

The majority view had relied, as pointed out, on Ostime (Inspector of Taxes) to say that the taxpayer cannot decide on

what principle his income is to be assessed and therefore the appellant's method of calculation should be rejected. But

I think what was missed is that any assessment must be done in accordance with the provisions of the Income Tax Act

whether the assessment is by the Taxpayer or by Inland Revenue. That was what Lord Guest said:

It can never rest with the taxpayer to decide on what principle his income is to be assessed for tax

purposes. The directors' decision can never be decisive of the matter for income tax purposes. The

assessment in addition to being consistent with normal accounting practice must be made in

accordance with the provisions of the Income Tax Act. (Emphasis added.)

Having said that I must add that quite clearly and obviously that the appellant's formula must also be rejected for it not

having been made in accordance with the provisions of the Income Tax.

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 148

The words of Rowlatt J on Cape Brandy Syndicate v IRC 12 TC 358 at 366:

Now of course it is said and urged by Sir William Finlay that in a taxing Act clear words are necessary

to tax the subject. But it is often endeavoured to give to that maxim a wide and fanciful construction. It

does not mean that the words are to be unduly restricted against the Crown or that there is to be any

discrimination against the Crown in such Acts. It means this, I think: it means that in taxation you have

to look simply at what is clearly said. There is no room for any intendment, there is no equity about a

tax: there is no presumption as to a tax; you imply nothing, but you look fairly at what is said and what

is said clearly and that is the tax. (Emphasis added.)

The conclusion is clear. There is nothing in the Act or the Regulations made thereunder to authorise the use of the

respondent's formula in ascertaining the adjusted income from each of the appellant's sources of income. The relevant

tax assessments for the years 1987 to 1992 are erroneous to the extent that the formula of the respondent was used to

determine the appellant's adjusted income.

As was stated earlier the appellant's formula cannot also be resorted to.

What then should be done in the absence of a prescribed procedure? The minority view merits consideration. The view

is that in the absence of any statutory procedure, the just and reasonable solution is to rely on the accepted principle

that revenue expenditure is deductible only against income revenue. Since there should not be allowed any deduction

of expenses against the element of principal of the lease rentals, which is capital in nature, it follows that no portion of

the deductible common expenses could have been expended in the production of that part of the gross income

represented by the element of principal. Thus the element of principal should not be taken into account for the purpose

of apportioning the 'non-capital' common expenses, which should be apportioned between the appellant's two business

portfolios according to the ratio between only the 'non-capital' income from each of the two portfolios.

16 In allowing the appeal the learned judge said:

Although there is no statutory provision for the method of apportioning the common expenses between two or more

sources of gross income, the formula advanced by the minority view is not at cross purposes with provisions of the Act.

A tax has to be collected and although there is no express provision how it should be calculated, one has to go back to

first principles. The formula rests on an accepted principle that revenue expenditure is deductible against income

revenue. It is also a just and reasonable solution to a problem which has not been addressed by the respondent under

powers which he has under s 36 of the Act. In contrast it has not been shown that either the respondent's or the

appellant's formula is in accordance with accepted principles of taxation.

The functions and powers of the court with regard to tax appeal cases was laid out in the case of Lower Perak

Cooperative Housing Society v KPHDN [1994] CLJ where the court adopted the principles in the case of Edwards v

Bairstow & Harrison [1956] AC 14 :

10

If the case contains anything ex facie which is bad in law and which bears upon the determination, it

is, obviously, erroneous in port of law. But, without any

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 149

such misconception appearing ex facie, it may be that the facts found are such that no person acting

judicially and properly instructed as to the relevant law could have come to the determination under

appeal. In those circumstances, too, the Court must intervene. It has no option but to assume that

there has been some misconception of the law and that this has been responsible for the

determination has been error in point of law. I do not think it matters whether this state of affairs is

described as one in which there is no evidence, is inconsistent with and contradictory of the

determination, or as one in which the true and only reasonable conclusion contradicts the

determination.

I am satisfied the majority view on the matter is erroneous on a point of law.

I allow the appeal. The assessments made by the respondent for the years of assessment 1987 to 1992 are amended

so that the formula for the apportionment of the common expenses for lease financing shall not take into account the

element of principal and that what should be apportioned between lease financing portfolio and non-leasing portfolio

shall be in accordance with the ratio between only the non-capital income from each of the two portfolios. Half costs to

the appellant.

17 The learned judge has taken the view that under s 36 of the Act '... it is expected that any special

treatment in computing the gross income has, perforce, to provide for some special treatment in computing

the adjusted income as well'. It must be observed that s 36(1) of the Act clearly enunciates that the Director

General may provide for special treatment in computing gross income and adjusted income only if he '... is

satisfied that there is a need for ...' doing so. It is a matter for him to decide. Under s 36(1)(a) and (b) of the

Act he may provide for such special treatment in the case of gross income or adjusted income or both. We

say this because the semi-colon followed by the conjunction 'and' between s 36(1)(a) and (b) means that

both the provisions must be construed disjunctively. In so saying we derive support from the judgment of the

(then) Supreme Court in Dato Mohamed Hashim Shamsuddin v Attorney General, Hong Kong [1986] 2 MLJ

112 where Abdoolcader SCJ said, even in the case of comma followed by the conjunction 'and', at p 122:

Its punctuation forms part of any statutory enactment and may be used as a guide to interpretation. The day is long

past when the courts would pay no heed to punctuation in any written law (Hanlon v Law Society [1981] AC 124) (at pp

197-198 per Lord Lowry), and the presence or absence of a comma may be highly significant (Re Steel (deceased),

Public Trustee v Christian Aid Society [1979] Ch 218;Marshall v Cottingham [1981] 3 All ER 8 (at p 12)). Section 16(1)

of the 1964 Act must in my view be read disjunctively in the light of the comma I have referred to which is significantly

followed by the conjunction 'and'.

18 It follows that there is nothing unusual or unlawful in the Director General having provided for special

treatment in the computation of gross income for leasing businesses without having made corresponding

provisions for the computation of adjusted income. It only means that he is not satisfied that there is a need

to do so.

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 150

19 The critical matter for consideration is the finding of the learned trial judge that the element of principal

should not be taken into account for the apportionment of the common expenses in lease financing as there

is no provision in the Act or in the 1986 Regulations prescribing the manner of doing so in respect of different

income sources.

20 The starting point in determining the correctness of the finding of the learned judge is the manner of

ascertaining the chargeable income of a person upon which tax is payable. This is governed by s 5 of the

Act which provides, inter alia, that a person's gross income from each source shall be ascertained in

accordance with Chapter 3 of Part III of the Act followed by an ascertainment of his adjusted income in

accordance with Chapter 4 of that Part the relevant provision of which is s 33(1) of the Act. This section

stipulates that the allowable expenses of a person for a source shall be deducted from the gross income of

that source. It must be observed that the opening words of the section, that is to say, 'Subject to this Act ...'

mean that the section must be modified, where necessary, in the light of other provisions in the Act or other

laws made under the authority of the Act. The 1986 Regulations is such a law under the latter category.

Regulation 2 of the 1986 Regulations provides that the gross income of a person from lease transactions

shall be deemed to be a separate and distinct business source from other activities of that person.

11

Regulation 3 of the 1986 Regulations provides that in the case of a leasing business the gross income shall

be the total rental received for the basis period for a year of assessment. The total rental would comprise the

principal and interest. It follows that the meaning of 'gross income' in s 33(1)of the Act must be construed in

the light of regs 2 and 3 of the 1986 Regulations. The result is that in the case of a leasing business the

gross income of a person shall be the principal and interest as a separate source for the purpose of

ascertaining his adjusted income under s 33(1) of the Act. Thus the contention of the respondent that the

gross income must be confined to the interest element of the leasing business is wholly unsustainable in law.

That is clear and ought to have been the end of the matter.

21 What, perhaps, has created some confusion is whether s 33(1) of the Act which prescribes the method of

ascertaining '...the adjusted income of a person from a source ... shall be an amount ascertained by

deducting from the gross income of that person from that source ...' authorises the apportionment of common

expenses where there are two or more sources of income. It is clear that s 33(1) of the Act is applicable

even where there are two or more sources of income. This flows clearly from s 5(c) of the Act which provides

that the '... adjusted income from each source ... for the basis period for that year shall be ascertained in

accordance with Chapter 4 of that part'. The word 'each' in the phrase referred to contemplates the existence

of more than one source of income. Therefore s 33(1)of the Act which must be read with s 5(c) of the Act is

applicable even in cases where a person has more than one source of income. It must, however, be

remembered that if a person has two or

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 151

more sources of income then his adjusted income must, as provided by s 33(1) of the Act, be ascertained

separately source by source. This is necessary as the expenses allowed for one source can only be those

incurred in respect of the gross income of that source. Where there are two or more sources of income for a

person and the expenses are identifiable and separable there will be no difficulty in ascertaining the adjusted

income for each source. However, there will be instances when the expenses of two or more sources are not

separable as they are common to the sources. As s 33(1) of the Act requires a deduction of the expenses of

a source from the gross income of that source for the purpose of ascertaining the adjusted income of the

sources the question that arises for determination is whether the section empowers the appellant to

apportion the expenses. The power to apportion the expenses can be implied in s 33(1) of the Act in view of

the need to ascertain the adjusted income. But taxing statutes are subject to a strict rule of construction. As

Rowlatt J said in Cape Brandy Syndicate v IRC [1921] 1 KB 64 at p 71:

It simply means that in a taxing Act one has to look merely at what is clearly said. There is no room for any intendment.

There is no equity about a tax. There is no presumption as to a tax. Nothing is to be read in, nothing is to be implied.

One can only look fairly at the language used.

22 If s 33(1)of the Act is to be strictly construed the appellant will be unable to identify the expenses

separately where they are mixed with the result that the adjusted income of the sources cannot be

ascertained. This will defeat the object of s 33(1) of the Act and bring the machinery of tax assessment to a

grinding halt. This will not happen in the interpretation of ordinary statutes as one of the salutary canons of

construction in such cases is that Parliament does not act in vain. The courts strongly lean against a

construction which reduces a statute to a futility. A statute must be so construed so as to make it effective

and operative on the principle expressed in the maxim ut res magis valeat quam pareat (that the thing may

rather have effect than be destroyed in order that the thing may be valid rather than invalid). A matter of

concern is whether this rule of construction can be resorted to in construing s 33(1)of the Act as taxing

statutes must be strictly construed. Since the section deals with the machinery of tax assessment and is for

the benefit of the taxpayer by providing for the ascertainment of the adjusted income it is not subjected to a

strict construction like ordinary taxing statutes. In this regard reference is made to Principles of Statutory

Interpretation by Justice GP Singh (6th Ed) p 505:

It must also be borne in mind that the rule of strict construction in the sense explained above applies primarily to

charging provisions in a taxing statute and has no application to a provision not creating a charge but laying down

machinery for its calculation or procedure for its collection, and such machinery provisions have to be construed by the

ordinary rule of construction (Gursahai v CIT AIR 1963 SC 1062). One important consideration in construing a

machinery section is that it should be so construed as to effectuate the liability imposed by the charging section and to

make the machinery workable -- ut res magis valeat quam peveat (NB Sanjana v Elphinston

2005 4 MLJ 138 at 152

Spinning & Weaving Mills AIR 1971 SC 2039). Similarly a machinery provision which enables the assessee to avail of

a concession or benefit conferred by a substantive provision in the Act is liberally construed (CIT v Kulu Valley

12

Transport Co Pvt Ltd AIR 1970 SC 1734).

23 Thus in order to ensure that s 33(1) of the Act is not rendered otiose the power of the appellant to

apportion common expenses must be construed as being implied and therefore an integral part of the

section; a construction that will be consistent with its object and purpose.

24 It is therefore clear that the respondent's gross income for the leasing business shall constitute the

principal and interest elements for the purpose of ascertaining its adjusted income as provided by law. The

exclusion of the principal element in the apportionment exercise in this case will be a clear violation of s

33(1) of the Act read with reg 3 of the 1986 Regulations. The common expenses incurred must be

apportioned pursuant to s 33(1) of the Act. The method of apportionment followed by the appellant is

therefore in compliance with the law. It is neither arbitrary nor a matter of discretion. In the upshot we allow

the appeal with costs here and below.

Appeal allowed with costs.

Reported by Loo Lai Mee

You might also like

- Soccer (Football) Contracts: An Introduction to Player Contracts (Clubs & Agents) and Contract Law: Volume 2From EverandSoccer (Football) Contracts: An Introduction to Player Contracts (Clubs & Agents) and Contract Law: Volume 2No ratings yet

- Ketua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri V Daya LeaDocument5 pagesKetua Pengarah Hasil Dalam Negeri V Daya Leachunlun87No ratings yet

- Income TaxDocument5 pagesIncome TaxDeniAxis WinnerNo ratings yet

- Tax Treaty Benefits Prevail Over RMO No. 1-2000Document7 pagesTax Treaty Benefits Prevail Over RMO No. 1-2000Jihan LlamesNo ratings yet

- CLJ_2005_4_810_Document9 pagesCLJ_2005_4_810_alliya natashaNo ratings yet

- Creba. v. Romulo. 614 Scra. 605Document18 pagesCreba. v. Romulo. 614 Scra. 605Joshua RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Deutsche Bank Ag Manila Branch VS CirDocument4 pagesDeutsche Bank Ag Manila Branch VS CirJen DeeNo ratings yet

- Creba V RomuloDocument18 pagesCreba V RomuloJuhainah TanogNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 160756Document12 pagesG.R. No. 160756Jason BuenaNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 160756Document16 pagesG.R. No. 160756Meah BrusolaNo ratings yet

- CREBA v. ROMULO 614 SCRA 605 G.R. No. 160756. March 9 2010Document8 pagesCREBA v. ROMULO 614 SCRA 605 G.R. No. 160756. March 9 2010arden1imNo ratings yet

- 153 - Chamber of Real Estate and Builders Association V Romulo (2010)Document3 pages153 - Chamber of Real Estate and Builders Association V Romulo (2010)Charvan CharengNo ratings yet

- ATTY VILLO TAX CASE DIGESTS: General PrinciplesDocument47 pagesATTY VILLO TAX CASE DIGESTS: General PrinciplesAbseniNalangKhoUyNo ratings yet

- Corporate Tax Free ExchangeDocument5 pagesCorporate Tax Free ExchangeNeptali MarotoNo ratings yet

- Deutsche Bank AG Manila Branch v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, G.R. No. 18850, August 19, 2013Document2 pagesDeutsche Bank AG Manila Branch v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, G.R. No. 18850, August 19, 2013Dominique VasalloNo ratings yet

- CREBA Vs RomuloDocument19 pagesCREBA Vs RomuloVincent OngNo ratings yet

- Various Issues Relating To Works ContractDocument5 pagesVarious Issues Relating To Works ContractApoorvnujsNo ratings yet

- CREBA Inc. vs. Romulo, G.R. No. 160756, March 9, 2010Document22 pagesCREBA Inc. vs. Romulo, G.R. No. 160756, March 9, 2010KidMonkey2299No ratings yet

- Swoct26 2 CP5Document11 pagesSwoct26 2 CP5MabdNo ratings yet

- 67 Philippine Airlines, Inc. vs. EduDocument12 pages67 Philippine Airlines, Inc. vs. EduMary Joy JoniecaNo ratings yet

- GR 179115Document19 pagesGR 179115MelgenNo ratings yet

- Chamber vs. Romulo 614 SCRA 605 2010Document17 pagesChamber vs. Romulo 614 SCRA 605 2010Jacinto Jr JameroNo ratings yet

- Creba V Exec Sec RomuloDocument18 pagesCreba V Exec Sec RomuloAnonymous qVilmbaMNo ratings yet

- PAL v. Edu, 164 SCRA 320Document14 pagesPAL v. Edu, 164 SCRA 320citizenNo ratings yet

- SMART V Dava0, CIR vs. CA, CIR v. UCBPDocument6 pagesSMART V Dava0, CIR vs. CA, CIR v. UCBPKath LeenNo ratings yet

- Corona, J.:: G.R.No.160756: March 9, 2010Document3 pagesCorona, J.:: G.R.No.160756: March 9, 2010Weena Joy C. LegalNo ratings yet

- Retainership AgreementDocument6 pagesRetainership Agreementrivar5957No ratings yet

- Oyu Tolgoi Investment AgreementDocument45 pagesOyu Tolgoi Investment AgreementOdbayar GurragchaaNo ratings yet

- American Chicle Co. v. United States, 316 U.S. 450 (1942)Document4 pagesAmerican Chicle Co. v. United States, 316 U.S. 450 (1942)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Tax ChallengeDocument18 pagesReal Estate Tax ChallengeJMae MagatNo ratings yet

- Chamber of Real Estate and Builders Associations Inc Vs The Hon Executive Secretary Alberto Romulo Et AlDocument20 pagesChamber of Real Estate and Builders Associations Inc Vs The Hon Executive Secretary Alberto Romulo Et AlMark Gabriel B. MarangaNo ratings yet

- First DivisionDocument45 pagesFirst DivisionmifajNo ratings yet

- The Provisions of Sections 28 To 44D Deal With The Method of Computing Income Under HeadDocument4 pagesThe Provisions of Sections 28 To 44D Deal With The Method of Computing Income Under HeadTwinkling starNo ratings yet

- Real Estate Groups Challenge Constitutionality of Minimum Corporate Tax and Creditable Withholding TaxDocument14 pagesReal Estate Groups Challenge Constitutionality of Minimum Corporate Tax and Creditable Withholding TaxJohn Basil ManuelNo ratings yet

- Maharashtra National Law University Contract Law AssessmentDocument12 pagesMaharashtra National Law University Contract Law AssessmentAkanksha BohraNo ratings yet

- REVISION Notes On Interpretation OF TAXING STATUTES - LLB 6TH SEM - Interpretation of StatutesDocument5 pagesREVISION Notes On Interpretation OF TAXING STATUTES - LLB 6TH SEM - Interpretation of StatutesRishabh JainNo ratings yet

- Direct Taxes Circular - SecDocument26 pagesDirect Taxes Circular - SecnalluriimpNo ratings yet

- Western Minolco V CirDocument7 pagesWestern Minolco V CirBenedick LedesmaNo ratings yet

- Chamber of Real Estate and Builders' Association v. RomuloDocument19 pagesChamber of Real Estate and Builders' Association v. RomuloNxxxNo ratings yet

- Marcopper Mining Corporation v. NLRC, G.R. No. 103525, 29 March 1996Document9 pagesMarcopper Mining Corporation v. NLRC, G.R. No. 103525, 29 March 1996JMae MagatNo ratings yet

- TAXATION 1 Smith V CommissionerDocument79 pagesTAXATION 1 Smith V CommissionerJoan Margaret GasatanNo ratings yet

- Taxation CasesDocument296 pagesTaxation CasesshelNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Tax Strict StatuteDocument6 pagesInterpretation of Tax Strict StatuteShruti SoniNo ratings yet

- Case No. 49 G.R. No. L-13325 April 20, 1961 Santiago Gancayco, Petitioner, vs. The Collector of INTERNAL REVENUE, RespondentDocument5 pagesCase No. 49 G.R. No. L-13325 April 20, 1961 Santiago Gancayco, Petitioner, vs. The Collector of INTERNAL REVENUE, RespondentLeeNo ratings yet

- Union of IndiaDocument47 pagesUnion of IndiaayushNo ratings yet

- Tax Implications of AOP and JDADocument8 pagesTax Implications of AOP and JDAParameswar ERNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 109289 Tan V Del Rosario October 3, 1994 DigestDocument3 pagesG.R. No. 109289 Tan V Del Rosario October 3, 1994 DigestRafie Bonoan100% (1)

- J.N. Ledbetter and R.W. Ledbetter v. United States, 792 F.2d 1015, 11th Cir. (1986)Document7 pagesJ.N. Ledbetter and R.W. Ledbetter v. United States, 792 F.2d 1015, 11th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Interpretation of Taxing Statutes Taxing StatuteDocument7 pagesInterpretation of Taxing Statutes Taxing StatuteSubhayan Boral100% (1)

- Investment Contract 02Document45 pagesInvestment Contract 02ahadi abdullahNo ratings yet

- General Principles CasesDocument294 pagesGeneral Principles CasesAnne OcampoNo ratings yet

- CFD 2004-3 Mello Roos Petition ApprovalDocument12 pagesCFD 2004-3 Mello Roos Petition ApprovalBrian DaviesNo ratings yet

- Republic of The Philippines Manila: CREBA, Inc. v. Romulo G.R. No. 160756Document18 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Manila: CREBA, Inc. v. Romulo G.R. No. 160756Jopan SJNo ratings yet

- Full Text Due Process ClauseDocument79 pagesFull Text Due Process ClauseAnonymous 2UPF2xNo ratings yet

- 2 CREBA Vs ROMULO INCOME TAXATIONDocument2 pages2 CREBA Vs ROMULO INCOME TAXATIONSu Kings AbetoNo ratings yet

- CTA CasesDocument177 pagesCTA CasesJade Palace TribezNo ratings yet

- Taxation Law Pre-Bar Notes 2017-SupplementalDocument7 pagesTaxation Law Pre-Bar Notes 2017-SupplementalPnix HortinelaNo ratings yet

- CREBA Vs RomuloDocument10 pagesCREBA Vs RomuloAndrea Peñas-ReyesNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 12 Q A Chapter 17 RaibornDocument7 pagesTutorial 12 Q A Chapter 17 Raibornchunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 5 Q & ADocument6 pagesTutorial 5 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Minimization Problem: Minimum Number Cover All ZerosDocument5 pagesMinimization Problem: Minimum Number Cover All Zeroschunlun87No ratings yet

- Topic 1: Decision Analysis 1. Six Steps in Decision TheoryDocument8 pagesTopic 1: Decision Analysis 1. Six Steps in Decision Theorychunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 4 Q & ADocument5 pagesTutorial 4 Q & Achunlun87100% (1)

- Tutorial 9 Q & ADocument2 pagesTutorial 9 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 13 Q & A - StudentsDocument2 pagesTutorial 13 Q & A - Studentschunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial-12 Q - Chapter-17-RaibornDocument4 pagesTutorial-12 Q - Chapter-17-Raibornchunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 14 Q & ADocument4 pagesTutorial 14 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 8 Q & ADocument3 pagesTutorial 8 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 11 Q & A StudentsDocument4 pagesTutorial 11 Q & A Studentschunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 2 Q & ADocument6 pagesTutorial 2 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Advanced Auditing Tutorial 12 Q&ADocument2 pagesAdvanced Auditing Tutorial 12 Q&Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Advantages of statistical sampling over judgement samplingDocument4 pagesAdvantages of statistical sampling over judgement samplingchunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 7 Q & ADocument5 pagesTutorial 7 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 6 Q & ADocument4 pagesTutorial 6 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Assignment Question 3Document2 pagesAssignment Question 3chunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 7 Q & ADocument5 pagesTutorial 7 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Case Preparation ChartDocument6 pagesCase Preparation Chartchunlun87No ratings yet

- Answer Topic 1 Part 2 Exc2 (C)Document1 pageAnswer Topic 1 Part 2 Exc2 (C)chunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 1 Q & ADocument2 pagesTutorial 1 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Tutorial 3 Q & ADocument3 pagesTutorial 3 Q & Achunlun87No ratings yet

- Assignment Topic Subject Code: Bac 4685 Goods and Service Tax (GST)Document2 pagesAssignment Topic Subject Code: Bac 4685 Goods and Service Tax (GST)chunlun87No ratings yet

- Case Preparation ChartDocument6 pagesCase Preparation Chartchunlun87No ratings yet

- Adv Tax Tut1Document1 pageAdv Tax Tut1chunlun87No ratings yet

- Part 2 - Discussion On The Case About Our Opinion: Respondent (R)Document2 pagesPart 2 - Discussion On The Case About Our Opinion: Respondent (R)chunlun87No ratings yet

- Adv Tax Assignment (With Cover)Document14 pagesAdv Tax Assignment (With Cover)chunlun87No ratings yet

- AA Money Changing 151014 Legal Review (For Finance)Document31 pagesAA Money Changing 151014 Legal Review (For Finance)chunlun87No ratings yet

- Adv Tax AssignmentDocument14 pagesAdv Tax Assignmentchunlun87No ratings yet

- MAF680 Case: Chicken Run: Group MembersDocument12 pagesMAF680 Case: Chicken Run: Group MemberscasmaliaNo ratings yet

- Interpreting The Feelings of Other People Is Not Always EasyDocument4 pagesInterpreting The Feelings of Other People Is Not Always EasyEs TrungdungNo ratings yet

- GIMPA SPSG Short Programmes 10.11.17 Full PGDocument2 pagesGIMPA SPSG Short Programmes 10.11.17 Full PGMisterAto MaisonNo ratings yet

- Instructor'S Manual Instructor'S Manual: An Introduction To Business Management 8Document18 pagesInstructor'S Manual Instructor'S Manual: An Introduction To Business Management 8arulsureshNo ratings yet

- Daily LogDocument14 pagesDaily Logdempe24No ratings yet

- Senior Development and Communications Officer Job DescriptionDocument3 pagesSenior Development and Communications Officer Job Descriptionapi-17006249No ratings yet

- Eco Bank Power Industry AfricaDocument11 pagesEco Bank Power Industry AfricaOribuyaku DamiNo ratings yet

- Industrial Visit ReportDocument6 pagesIndustrial Visit ReportgaureshraoNo ratings yet

- ALO StrategyDocument1 pageALO StrategyChayse BarrNo ratings yet

- Public Finance Exam A2 JHWVLDocument3 pagesPublic Finance Exam A2 JHWVLKhalid El SikhilyNo ratings yet

- KDF Structural PDFDocument2 pagesKDF Structural PDFbikkumalla shivaprasadNo ratings yet

- "Potential of Life Insurance Industry in Surat Market": Under The Guidance ofDocument51 pages"Potential of Life Insurance Industry in Surat Market": Under The Guidance ofFreddy Savio D'souzaNo ratings yet

- Shoppers Paradise Realty & Development Corporation, vs. Efren P. RoqueDocument1 pageShoppers Paradise Realty & Development Corporation, vs. Efren P. RoqueEmi SicatNo ratings yet

- PDF1902 PDFDocument190 pagesPDF1902 PDFAnup BhutadaNo ratings yet

- Globalization's Importance for EconomyDocument3 pagesGlobalization's Importance for EconomyOLIVER JACS SAENZ SERPANo ratings yet

- Arjun ReportDocument61 pagesArjun ReportVijay KbNo ratings yet

- Charter a Bus with Van Galder for Travel NeedsDocument2 pagesCharter a Bus with Van Galder for Travel NeedsblazeNo ratings yet

- Mahanagar CO OP BANKDocument28 pagesMahanagar CO OP BANKKaran PanchalNo ratings yet

- Print - Udyam Registration Certificate AnnexureDocument2 pagesPrint - Udyam Registration Certificate AnnexureTrupti GhadiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 16 Planning The Firm's Financing Mix2Document88 pagesChapter 16 Planning The Firm's Financing Mix2api-19482678No ratings yet

- SHFL Posting With AddressDocument8 pagesSHFL Posting With AddressPrachi diwateNo ratings yet

- Rationale Behind The Issue of Bonus SharesDocument31 pagesRationale Behind The Issue of Bonus SharesSandeep ReddyNo ratings yet

- TransportPlanning&Engineering PDFDocument121 pagesTransportPlanning&Engineering PDFItishree RanaNo ratings yet

- MCQs On Transfer of Property ActDocument46 pagesMCQs On Transfer of Property ActRam Iyer75% (4)

- Mintwise Regular Commemorative Coins of Republic IndiaDocument4 pagesMintwise Regular Commemorative Coins of Republic IndiaChopade HospitalNo ratings yet

- Environment PollutionDocument6 pagesEnvironment PollutionNikko Andrey GambalanNo ratings yet

- Challenge of Educating Social EntrepreneursDocument9 pagesChallenge of Educating Social EntrepreneursRapper GrandyNo ratings yet

- Monitoring Local Plans of SK Form PNR SiteDocument2 pagesMonitoring Local Plans of SK Form PNR SiteLYDO San CarlosNo ratings yet

- Partner Ledger Report: User Date From Date ToDocument2 pagesPartner Ledger Report: User Date From Date ToNazar abbas Ghulam faridNo ratings yet

- Society in Pre-British India.Document18 pagesSociety in Pre-British India.PřiýÂňshüNo ratings yet

- Form 16 TDS CertificateDocument2 pagesForm 16 TDS CertificateMANJUNATH GOWDANo ratings yet