Professional Documents

Culture Documents

International Monetary Theory and Policy

Uploaded by

happystoneOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

International Monetary Theory and Policy

Uploaded by

happystoneCopyright:

Available Formats

Department of Economics Instructor: Martn Uribe

Columbia University Spring 2013

Economics W4505

International Monetary Theory and Policy

Homework 2

Due February 6 in class

Current Account Sustainability

1. Consider a two-period economy that has at the beginning of period 1 a net foreign asset position of

-100. In period 1, the country runs a current account decit of 5 percent of GDP, and GDP in both

periods is 120. Assume the interest rate in periods 1 and 2 is 10 percent.

(a) Find the trade balance in period 1 (TB

1

), the current account balance in period 1 (CA

1

), and

the countrys net foreign asset position at the beginning of period 2 (B

1

).

(b) Is the country living beyond its means? To answer this question nd the countrys current account

balance in period 2 and the associated trade balance in period 2. Is this value for the trade balance

feasible? [Hint: Keep in mind that the trade balance cannot exceed GDP.]

(c) Now assume that in period 1, the country runs instead a much larger current account decit of

10 percent of GDP. Find the countrys net foreign asset position at the end of period 1, B

1

. Is

the country living beyond its means? If so, show why.

2. Ever since the 1980s, when a long sequence of external decits began, many economists and observers

have shown concern about the sustainability of the U.S. current account. Use question 1 and the

concepts developed in chapter 2 of the book as a theoretical basis to provide a critical analysis of the

attached article from the November 27, 2003 edition of the The Economist magazine entitled Stop

worrying and love the decit.

3. Suppose that, at the time of the writing of this article, its author had known the path of the

U.S. economy to the present. How do you think his predictions would have changed?

1

Stop worrying and love the decit

Nov 27th 2003

From The Economist print edition

Americas current-account decit poses few dangers, says Alan Greenspan. Except to Europeans

In the past year the United States has run up a current-account decit of more than $500 billion. Some

think that the line of credit extended by the rest of the world to America is dangerously long. As Kenneth

Rogo, formerly chief economist of the International Monetary Fund, puts it, foreign creditors give poor

countries just enough rope to hang themselves, but they are giving the Americans enough rope to tie the

noose around their neck several times. Most countries with a decit of such size would nd the downward

pressure on their currencies and the upward pressure on bond yields irresistible. They would be forced to

cut their expenditure and switch their spending from imports to domestic production. But for America the

gallows do not beckon yet, according to a recent speech

1

by Alan Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal

Reserve, at a conference sponsored by The Economist and the Cato Institute. Admittedly, Americans

demands on the worlds savings are greater than ever. But Mr Greenspan argues that, thanks to spreading

globalisation, the pool of savings on oer in todays global capital markets is deeper and more liquid than

ever. The markets continue to furnish America with the money it needs without demanding higher yields

in return. In a recent paper Michael Dooley,

2

of the University of California at Santa Cruz, and David

Folkerts-Landau and Peter Garber, of Deutsche Bank, come to the same sanguine conclusion from opposite

premises: the decit is manageable not because todays world is unique but because it replicates the post-

war Bretton Woods era. America is once again at the centre of an international monetary system. On

the periphery, where post-war Europe once stood, now stands East Asia, with its cosseted capital markets

and fear of oating against the dollar. The players have changed, but the rules of the game are much

the same. Under Bretton Woods, the Europeans, as they regained their exporting strength, amassed ever

greater dollar claims on America. Similarly, under todays revived Bretton Woods system, the East Asians

hoard their export earnings in low-yielding dollar assets, such as Treasury bills. What East Asia hoards,

America happily spends: the inow of Asian capital keeps American interest rates low and demand high.

Moreover, America tends to spend its cheap East Asian loans on cheap East Asian goods. America and

Europe used to enjoy a similar relationship. As Jacques Rue, a French economist, put it in 1965: If I had

an agreement with my tailor that whatever money I pay him returns to me the very same day as a loan, I

would have no objection at all to ordering more suits from him. America gets more suits, but what do the

East Asian tailors get out of it? Yields on safe, dollar assets are low and the opportunity cost is high, given

better returns at home or elsewhere. Messrs Dooley, Folkerts-Landau and Garber argue that East Asias

governments are accumulating dollar assets as a by-product of a strategy of export-led growth. East Asia

is prepared to forgo better returns in order to keep its exchange rates down and export demand up. This

allows the regions industries to compete on world markets and attract foreign investment. To stretch Mr

Rogos metaphor, the rope East Asia extends to America is not a noose but a tow-line, which will gradually

pull Asian economies towards greater prosperity. Others, such as Ronald McKinnon of Stanford University,

think that American proigacy has trapped East Asia into running current-account surpluses. The region is

forced to acquire dollar assets in order to avoid exchange-rate appreciation and deation. Under the original

Bretton Woods system, Mr McKinnon points out, America borrowed on a short-term basis from Europe,

but lent long, making enormous direct investments in the rebuilding of Europes war-blasted capital stock.

These days America (direct investments in China notwithstanding) borrows short in order to spend.

Slow change, or slower The $500 billion question, however, is whether Americas decit is sustainable.

The authors believe that the current system can endure, but that it will change. East Asia will continue to

lend to America until the surplus labour in its hinterlands is absorbed into its export industries, its nancial

system has matured and its currencies are ready to oat. And after East Asia has graduated from the

economic periphery, as Europe did before it, South Asia may take its place. Mr Greenspan, by contrast,

thinks Americas build-up of foreign debt must slow and eventually be reversed. But he is condent of a soft

landing: market forces will incrementally defuse the decit. The dollar may fall and bond yields rise, but

America is exible enough to adjust painlessly. Messrs Dooley, Folkerts-Landau and Garber put their faith

in the rigged exchange rates and regulated capital markets of Asia. Mr Greenspan puts his faith in market

1

www.federalreserve.gov/boarddocs/speeches/2003/20031120/default.htm.

2

An Essay on the Revived Bretton Woods System. NBER Working Paper no. 9971, September 2003:

www.nber.org/papers/w9971.

2

forces and the exibility of America. None of them thinks America should lose any sleep over its current-

account decit. All of them caution against protectionism, of which there have recently been unnerving signs.

Most of the discomfort caused by Americas decit will be felt neither in Asia nor in America but in Europe.

European investors may be growing less willing to underwrite American borrowing for miserable returns:

according to Morgan Stanley, they sold $403m-worth of American stocks, bonds and notes in September

after purchasing $28 billion-worth a month between January and August. Meanwhile, European exporters

are losing markets, squeezed out by an appreciating euro. However much rope East Asia provides, European

necks are in the noose.

Copyright c 2007 The Economist Newspaper and The Economist Group. All rights reserved.

3

You might also like

- Kennedy Balance of PaymentDocument5 pagesKennedy Balance of PaymentKinza ZaheerNo ratings yet

- Non State InstitutionsDocument21 pagesNon State InstitutionsAnne Morales86% (14)

- The Dollar Crisis: Causes, Consequences, CuresFrom EverandThe Dollar Crisis: Causes, Consequences, CuresRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- "This Is Our Currency, But Your Problem" Foreign Debt Accumulation and Its ImplicationsDocument12 pages"This Is Our Currency, But Your Problem" Foreign Debt Accumulation and Its ImplicationsJohnPapaspanosNo ratings yet

- The Renminbi: Soon To Be A Reserve Currency?Document15 pagesThe Renminbi: Soon To Be A Reserve Currency?richardck61No ratings yet

- Questioning USD As Global Reserve CurrencyDocument8 pagesQuestioning USD As Global Reserve CurrencyVincentiusArnoldNo ratings yet

- The Currency Puzzle (29!10!2010)Document21 pagesThe Currency Puzzle (29!10!2010)adhirajrNo ratings yet

- Teaching Note The Falling Dollar: Case SynopsisDocument3 pagesTeaching Note The Falling Dollar: Case Synopsisluica1968No ratings yet

- Global Financial SystemDocument1 pageGlobal Financial SystemMohamed H. ZakariaNo ratings yet

- Final Days of The Dollar 11 22 10Document13 pagesFinal Days of The Dollar 11 22 10exDemocratNo ratings yet

- The Euro-Dollar Market Friedman Principles - Jul1971Document9 pagesThe Euro-Dollar Market Friedman Principles - Jul1971Deep. L. DuquesneNo ratings yet

- The Dollar Dilemma The Worlds Top Currency Faces CompetitionDocument14 pagesThe Dollar Dilemma The Worlds Top Currency Faces Competitionevenwriter1No ratings yet

- Crisis of The UDocument10 pagesCrisis of The UAn TranNo ratings yet

- The Secret History of The Banking Crisis ToozeDocument8 pagesThe Secret History of The Banking Crisis ToozeHeinzNo ratings yet

- The Diminshing USD ($) TrendDocument5 pagesThe Diminshing USD ($) TrendGilani, ObaidNo ratings yet

- The Almighty DollarDocument5 pagesThe Almighty DollarAnantaNo ratings yet

- Collapse of The Us DollarDocument25 pagesCollapse of The Us Dollaranon-527257No ratings yet

- The Hegemony of The US DollarDocument4 pagesThe Hegemony of The US DollarJoey MartinNo ratings yet

- Eclectica 08-09Document4 pagesEclectica 08-09ArcturusCapitalNo ratings yet

- Bill Gross Investment Outlook May - 05Document7 pagesBill Gross Investment Outlook May - 05Brian McMorrisNo ratings yet

- Deficit Decline 1Document19 pagesDeficit Decline 1BlackEaglejsNo ratings yet

- Absolute Return Partners - The Absolute Return Letter - Beggar Thy Neighbor - September 2010Document7 pagesAbsolute Return Partners - The Absolute Return Letter - Beggar Thy Neighbor - September 2010AlexNo ratings yet

- Barron's: Why The Market Will Keep Sliding: Perry DDocument32 pagesBarron's: Why The Market Will Keep Sliding: Perry DAlbert L. PeiaNo ratings yet

- DPTX 0 0 11230 Jdip01 18655 0 74572Document79 pagesDPTX 0 0 11230 Jdip01 18655 0 74572Ahmed YousufzaiNo ratings yet

- 0811 The Greatest Trade of All Time 1Document6 pages0811 The Greatest Trade of All Time 1bi11yNo ratings yet

- Down The Rabbit Hole - The Eurodollar Market Is The Matrix Behind It AllDocument14 pagesDown The Rabbit Hole - The Eurodollar Market Is The Matrix Behind It AllAndyNo ratings yet

- TSW Journal Nov-Dec 2010Document16 pagesTSW Journal Nov-Dec 2010SchoolofWashingtonNo ratings yet

- The Euro-Dollar Market: Some First Principles: Increasing Concern Over Recurring U. S. InternationalDocument9 pagesThe Euro-Dollar Market: Some First Principles: Increasing Concern Over Recurring U. S. InternationalMarco ZucconiNo ratings yet

- "The Role of US Dollar As An International Currency Will Be Deluted in The World Economy by 2020". Do U Agree? ExplainDocument5 pages"The Role of US Dollar As An International Currency Will Be Deluted in The World Economy by 2020". Do U Agree? Explainamirol93No ratings yet

- Why Dollar Is Important: SUBMITTED TO: Professor: Dr. Mala Sane Batch: 2018-2020 2 SemesterDocument10 pagesWhy Dollar Is Important: SUBMITTED TO: Professor: Dr. Mala Sane Batch: 2018-2020 2 SemesterBipulKumarNo ratings yet

- Commodity Markets: 1. Default ImminentDocument5 pagesCommodity Markets: 1. Default Imminentapi-100874888No ratings yet

- Miller and ZhangDocument25 pagesMiller and ZhangChaman TulsyanNo ratings yet

- Friedman - The Eurodollar MarketDocument23 pagesFriedman - The Eurodollar MarketdifferenttraditionsNo ratings yet

- Topic-by-Topic 14 Major Emerging World Economies Lorna Corrected RTDocument8 pagesTopic-by-Topic 14 Major Emerging World Economies Lorna Corrected RTPowerOfEvilNo ratings yet

- Exam Review For Final Exam Review For FinalDocument4 pagesExam Review For Final Exam Review For FinalJack BorrisNo ratings yet

- The Politics of International Money and World Language: Essays in International FinanceDocument24 pagesThe Politics of International Money and World Language: Essays in International FinancenicolasricomesaNo ratings yet

- Term Paper On International Monetary SystemDocument6 pagesTerm Paper On International Monetary Systemafdtslawm100% (1)

- The Future of The DollarDocument6 pagesThe Future of The DollarFill NiuNo ratings yet

- Cohen, Benjamin J. "A Brief History of International Monetary Relations." (N.D.) : N. Pag. PrintDocument5 pagesCohen, Benjamin J. "A Brief History of International Monetary Relations." (N.D.) : N. Pag. PrintEmir MuminovicNo ratings yet

- IMF23. Annex Geo-Economic Fragmentation and The Future of MultilateralismDocument14 pagesIMF23. Annex Geo-Economic Fragmentation and The Future of MultilateralismNathalia GamboaNo ratings yet

- The Denigration of The Dollar and The Federal ReserveDocument3 pagesThe Denigration of The Dollar and The Federal ReserveYubin WooNo ratings yet

- Impact of U.S. Recession On India - An Empirical StudyDocument22 pagesImpact of U.S. Recession On India - An Empirical StudyashokdgaurNo ratings yet

- Martin Wolf ColumnDocument6 pagesMartin Wolf Columnpriyam_22No ratings yet

- Gagan Deep Singh Runner UpDocument10 pagesGagan Deep Singh Runner UpangelNo ratings yet

- The International Dollar Standard and The Sustainability of The U.S. Current Account DeficitDocument14 pagesThe International Dollar Standard and The Sustainability of The U.S. Current Account Deficitpmm1989No ratings yet

- Entrevista A Richard DuncanDocument10 pagesEntrevista A Richard DuncanEliseo RamosNo ratings yet

- Global Market Outlook July 2011Document8 pagesGlobal Market Outlook July 2011IceCap Asset ManagementNo ratings yet

- International Monetary SystemDocument6 pagesInternational Monetary SystemBora EfeNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document29 pagesChapter 2JeremiahOmwoyoNo ratings yet

- The Shadow Market: How a Group of Wealthy Nations and Powerful Investors Secretly Dominate the WorldFrom EverandThe Shadow Market: How a Group of Wealthy Nations and Powerful Investors Secretly Dominate the WorldRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- American Dollar: Crisis TimeDocument5 pagesAmerican Dollar: Crisis TimeAxel LippmanNo ratings yet

- Down The Rabbit Hole - The Eurodollar Market Is The Matrix Behind It AllDocument13 pagesDown The Rabbit Hole - The Eurodollar Market Is The Matrix Behind It AllKyle SalisburyNo ratings yet

- Ubs Investor Guide 5.27Document44 pagesUbs Investor Guide 5.27shayanjalali44No ratings yet

- Why The Euro Will Rival The Dollar PDFDocument25 pagesWhy The Euro Will Rival The Dollar PDFDaniel Lee Eisenberg JacobsNo ratings yet

- 11-14-11 What's Driving GoldDocument4 pages11-14-11 What's Driving GoldThe Gold SpeculatorNo ratings yet

- When Currencies Collapse - Barry Eichengreen PDFDocument11 pagesWhen Currencies Collapse - Barry Eichengreen PDFtakzacharNo ratings yet

- Barclays 2 Capital David Newton Memorial Bursary 2006 MartDocument2 pagesBarclays 2 Capital David Newton Memorial Bursary 2006 MartgasepyNo ratings yet

- Economics ProjectDocument20 pagesEconomics ProjectSiddhesh DalviNo ratings yet

- Better, Stronger, Faster: The Myth of American Decline . . . and the Rise of a New EconomyFrom EverandBetter, Stronger, Faster: The Myth of American Decline . . . and the Rise of a New EconomyRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (1)

- Globalisation Fractures: How major nations' interests are now in conflictFrom EverandGlobalisation Fractures: How major nations' interests are now in conflictNo ratings yet

- The Global Crash of 2015 and What You Can Do to Protect YourselfFrom EverandThe Global Crash of 2015 and What You Can Do to Protect YourselfNo ratings yet

- Class Note (Week 2)Document7 pagesClass Note (Week 2)happystoneNo ratings yet

- Business Foundation Outline (Translate)Document1 pageBusiness Foundation Outline (Translate)happystoneNo ratings yet

- Business Foundation Outline (Translate)Document1 pageBusiness Foundation Outline (Translate)happystoneNo ratings yet

- Business and Economics FundamentalsDocument1 pageBusiness and Economics FundamentalshappystoneNo ratings yet

- Advanced Corporate Finance Course Outline (Translated)Document1 pageAdvanced Corporate Finance Course Outline (Translated)happystoneNo ratings yet

- Fact SheetDocument2 pagesFact SheethappystoneNo ratings yet

- Class Notes (Week 1)Document2 pagesClass Notes (Week 1)happystoneNo ratings yet

- Specified The Allocation Bases and The OrderDocument3 pagesSpecified The Allocation Bases and The OrderhappystoneNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0167923612003120 MainDocument15 pages1 s2.0 S0167923612003120 MainhappystoneNo ratings yet

- Creative OR Modeling Using Excel To Solve Combinatorial Programming ProblemsDocument12 pagesCreative OR Modeling Using Excel To Solve Combinatorial Programming Problemskgirish_vNo ratings yet

- Assignment Questions Case24Document1 pageAssignment Questions Case24happystoneNo ratings yet

- Lectures 6 11Document40 pagesLectures 6 11happystoneNo ratings yet

- HIGGDocument3 pagesHIGGhappystoneNo ratings yet

- ACCT101 2010-2011 TERM1 Sample Final ExamDocument12 pagesACCT101 2010-2011 TERM1 Sample Final ExamhappystoneNo ratings yet

- Fall 2013 Cusato 336Document2 pagesFall 2013 Cusato 336happystoneNo ratings yet

- QuizDocument5 pagesQuizhappystoneNo ratings yet

- CH 12Document48 pagesCH 12happystoneNo ratings yet

- CH 08Document33 pagesCH 08happystoneNo ratings yet

- International Monetary Theory and PolicyDocument1 pageInternational Monetary Theory and PolicyhappystoneNo ratings yet

- FAAADocument8 pagesFAAAhappystoneNo ratings yet

- CH 08Document33 pagesCH 08happystoneNo ratings yet

- YTP Application FormDocument2 pagesYTP Application FormhappystoneNo ratings yet

- CH 01Document29 pagesCH 01happystoneNo ratings yet

- International Monetary Theory and PolicyDocument1 pageInternational Monetary Theory and PolicyhappystoneNo ratings yet

- Describe Persistently Unequal World Distribution of Income and The Evidence On Its CausesDocument7 pagesDescribe Persistently Unequal World Distribution of Income and The Evidence On Its CauseshappystoneNo ratings yet

- A Model of The Current Account: Costas Arkolakis Teaching Assistant: Yijia LuDocument21 pagesA Model of The Current Account: Costas Arkolakis Teaching Assistant: Yijia LuhappystoneNo ratings yet

- International Monetary Theory and Policy: U 1 U 2 U 1 U 2 E 1 E 2 E 1 E 2 U 1 U 2 E 1 E 2Document2 pagesInternational Monetary Theory and Policy: U 1 U 2 U 1 U 2 E 1 E 2 E 1 E 2 U 1 U 2 E 1 E 2happystoneNo ratings yet

- International Monetary Theory and Policy: T 1 T 2 N 1 N 2 0Document2 pagesInternational Monetary Theory and Policy: T 1 T 2 N 1 N 2 0happystoneNo ratings yet

- Ar2013 1Document76 pagesAr2013 1happystoneNo ratings yet

- Lecture1-2 Balance of PaymentsDocument22 pagesLecture1-2 Balance of PaymentshridaybikashdasNo ratings yet

- Valuation 2 Financial Statement AnalysisDocument19 pagesValuation 2 Financial Statement Analysisimperius784No ratings yet

- Amira Berdikari - Jurnal Khusus - Hanifah Hilyah SyahDocument9 pagesAmira Berdikari - Jurnal Khusus - Hanifah Hilyah Syahreza hariansyah100% (1)

- 2011 M1 ProspectusDocument130 pages2011 M1 ProspectusStanton OvertonNo ratings yet

- E - Portfolio Assignment MacroDocument8 pagesE - Portfolio Assignment Macroapi-316969642No ratings yet

- UTOPIA Key Terms and Definitions PDFDocument8 pagesUTOPIA Key Terms and Definitions PDFSherilyn Gautama100% (2)

- Financial Statement and The Reporting Entity.Document8 pagesFinancial Statement and The Reporting Entity.Mikki Miks AkbarNo ratings yet

- Modi Bats For Unlocking Economy, Cms Divided: He Conomic ImesDocument12 pagesModi Bats For Unlocking Economy, Cms Divided: He Conomic ImesyodofNo ratings yet

- A222 BWBB3193 Topic 04 Management of Risk in BankingDocument38 pagesA222 BWBB3193 Topic 04 Management of Risk in BankingNurFazalina AkbarNo ratings yet

- International Corporate Finance 11 Edition: by Jeff MaduraDocument34 pagesInternational Corporate Finance 11 Edition: by Jeff MaduraMahmoud SamyNo ratings yet

- Cost Behaviour & Decision Making - HodDocument65 pagesCost Behaviour & Decision Making - Hodsrimant100% (2)

- Bài 12 - Bài tập thực hànhDocument2 pagesBài 12 - Bài tập thực hànhDuyên BùiNo ratings yet

- DragonpayDocument3 pagesDragonpayJamel YusophNo ratings yet

- Purchase Order: 3015 Lulu HM # Al Messila, Doha 4740707390Document1 pagePurchase Order: 3015 Lulu HM # Al Messila, Doha 4740707390IzzathNo ratings yet

- CashTOa JPDocument11 pagesCashTOa JPDarwin LopezNo ratings yet

- Elvis Products International Common-Size Income Statement For The Year Ended Dec. 31, 1997 ($ 000's)Document5 pagesElvis Products International Common-Size Income Statement For The Year Ended Dec. 31, 1997 ($ 000's)askdgasNo ratings yet

- 9706 s04 MsDocument20 pages9706 s04 Msroukaiya_peerkhanNo ratings yet

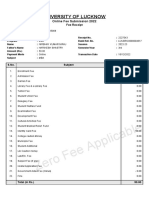

- Fee Receipt - Lucknow UniversityDocument3 pagesFee Receipt - Lucknow UniversityNirbhay NirajNo ratings yet

- Appendix 1: Sample Limited Partnership AgreementDocument70 pagesAppendix 1: Sample Limited Partnership AgreementectrimbleNo ratings yet

- Quizzer #8 PPEDocument13 pagesQuizzer #8 PPEAseya CaloNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument65 pagesProjectsantoshg939401No ratings yet

- Solved Jim and Andrea Kerslake Want To Open A Restaurant inDocument1 pageSolved Jim and Andrea Kerslake Want To Open A Restaurant inAnbu jaromiaNo ratings yet

- EAIF Review 2009Document33 pagesEAIF Review 2009Marius AngaraNo ratings yet

- Homework On Statement of Cash FlowsDocument2 pagesHomework On Statement of Cash FlowsAmy SpencerNo ratings yet

- Borosil Annual ReportDocument173 pagesBorosil Annual Reportrobingarg_professionalNo ratings yet

- L1 - JN - Financial Statement Analysis 2024 V1Document66 pagesL1 - JN - Financial Statement Analysis 2024 V1niketshah75oNo ratings yet

- Credit and Early Banking Practices in The Ottoman Empire: The Bank of Smyrna (1842-1843)Document32 pagesCredit and Early Banking Practices in The Ottoman Empire: The Bank of Smyrna (1842-1843)fauzanrasipNo ratings yet

- Balance Sheet or Statement of Financial PositionDocument52 pagesBalance Sheet or Statement of Financial PositionkarishmaNo ratings yet

- Model Question For Account409792809472943360Document8 pagesModel Question For Account409792809472943360yugeshNo ratings yet

- BBDC Elearning PDFDocument100 pagesBBDC Elearning PDFlakshmipathihsr64246100% (1)