Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Obesity As Collateral Damage: A Call For Papers On The Obesity Epidemic

Uploaded by

Sandeep Kumar0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 views3 pagesASTROLOGY

Original Title

jphp201114a

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentASTROLOGY

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

31 views3 pagesObesity As Collateral Damage: A Call For Papers On The Obesity Epidemic

Uploaded by

Sandeep KumarASTROLOGY

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Editorial

Obesity as collateral damage: A call for papers

on the Obesity Epidemic

Journal of Public Health Policy (2011) 32, 143145. doi:10.1057/jphp.2011.14

In this call for papers, we encourage authors to submit articles

considering how to change the behavior of the food industry. Heres why.

Since we published the Special Section on Legal Approaches to the

Obesity Epidemic from the Public Health Advocacy Institute in 2004,

1

the Journal has fully engaged in debates over obesity its causes and

how to prevent it. (The JPHP website displays a collection of articles

on nutrition and obesity at http://www.palgrave-journals.com/jphp/

collections/food_and_obesity_collection.html.) Obesity surely consti-

tutes an epidemic a global phenomenon, seen in low income, as well

as affluent countries. It often coexists with hunger and malnutrition.

What are the underlying, root causes of obesity and its public health

consequences?

We know that almost every country has created policies to prepare

for and to avoid famine and food shortages that might damage their

people, and disrupt their economies and social fabric. In 2010, Russia

blocked wheat exports when bad weather destroyed its crops. The

United States government, since early in the last century, has supported

food production through subsidies and other policies, resulting in large

surpluses of food commodities, meat, and calories. These policies

maintain the price of food at artificially low levels and have reduced the

percentage of personal income spent on food to the lowest in the world.

In this artificial market, large food producers and corporations

Big Agriculture and Big Food became very profitable. The first set

of countries to experience economic concentration, starting before

the Great Depression the United States, Japan, and countries in

Europe found that just a few corporations came to dominate each

segment of the food industry. These firms integrated vertically to the

point where they now own, and increase their profitability from,

every step in the chain of production from farms to wholesale

distribution of processed foods. In the past 30 years in the United

States, for example, consolidation by corporations means that the

number of separately owned hog farms decreased by nearly 90 per

cent, and only four per cent of the millions of hogs raised by US

r 2011 Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 0197-5897 Journal of Public Health Policy Vol. 32, 2, 143145

www.palgrave-journals.com/jphp/

farmers are ever sold on the open market.

2

Today, US farms and

farmers contribute only a small part of the final value of food; what

is raised on farms costs only 20 cents of the food dollar, on average.

3

The rest is value added in the remaining steps in the chain: supply,

distribution, and marketing. This explains why companies seek

vertical integration; and why they manufacture so many processed

foods. The first reduces cost of inputs and the second introduces

opportunities to increase the value or price of the consumer product.

The processed foods that reach US consumers, and increasingly

people in all high-income countries, are remarkably inexpensive,

tasty, and convenient to prepare. They are intensely marketed and

highly profitable to corporate producers. Where does the profit come

from? In part, it comes from use of subsidized commodities. But

profits are also generated by capturing increasingly larger shares of

the market and by selling the population more food and calories

than it needs. In this marketing environment, obesity is collateral

damage.

The food industrys ultimately anti-social behavior whether

conscious or inadvertent is spreading globally. In higher income

countries, it is ubiquitous, whereas in places where people have less

disposable income, it is but the camels nose under the tent. Thus,

effective strategies to reduce obesity may vary depending on

penetration by the industry and less developed nations may still

have more opportunities to avoid obesity, by getting ahead of the

curve.

Signs of marketing efforts by multi-national food corporations are

appearing everywhere in developing countries. In 2010, The New

York Times reported that international sales accounted for half of

PepsiCos revenue, whereas three-fourths of Coca-Cola sales occur

outside the United States; both companies are US corporations. Kraft

(also in the United States) reported a tripling of profits on the

strength of overseas markets. And the worlds largest food company,

Nestle, headquartered in Switzerland, with US $101 billion in sales,

is omnipresent. Rates of obesity are climbing so rapidly in the

developing world that the phenomenon has gained its own name: the

nutrition transition.

The tobacco analogy: this industry, which deliberately encouraged

children to become addicted to cigarettes as early as possible, then

continued to market cigarettes even once well aware of the health

dangers. We now know the health dangers of obesity, but the

Editorial

144 r 2011 Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 0197-5897 Journal of Public Health Policy Vol. 32, 2, 143145

epidemic continues. To protect the public, perhaps we can learn from

anti-smoking efforts about means to constrain the food industry.

4

As public health advocates, we know all too well that teaching the

worlds population about the dangers of obesity and the need to avoid

obesogenic foods that are inexpensive, tasty, and convenient, will never

work if food corporations are permitted to continue to spend massively

to encourage the public to eat more of their products. Efforts to control

obesity will have to enlist the public to focus on behavior, with a shift

from a sole focus on citizens to a new one on the behavior of food

corporations.

Food is not cigarettes. We must eat to live. We cannot eliminate

the food industry to reverse the obesity epidemic, but we can

constrain its anti-social behavior. This Editorial is posted on JPHPs

website as a call for papers. We encourage authors to reach beyond

the kind studies of policies on eating and activity that we receive so

frequently. We have come to believe that research studies concen-

trating on personal behavior and responsibility as causes of the

obesity epidemic do little but offer cover to an industry seeking to

downplay its own responsibility.

Instead, we urge authors to submit articles that consider how to

understand and change the behavior of the food industry. As a starting

point for thinking about how to approach this topic, we ask: does the

industry need to overfeed the population to remain profitable?

References

1. Journal of Public Health Policy. (2004) Special issue section: Legal approaches to the obesity

epidemic 25(34): 346434.

2. New York Times (2010) Editorial: Reforming meat. 7 September, http://www.nytimes.com/

2010/09/08/opinion/08wed3.html?scp=9&sq=hog%20production&st=cse.

3. USDA. (2008) Briefing room: Food marketing system in the U.S.: Price spreads from farm to

consumer, http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/FoodMarketingSystem/pricespreads.htm, accessed

February 2011.

4. Brownell, K.D. and Warner, K.E. (2009) The perils of ignoring history: Big tobacco played

dirty and millions died. How similar is big food? The Milbank Quarterly 87(1): 259294.

Anthony Robbins

Co-Editor,

E-mail: anthony.robbins@tufts.edu

Marion Nestle

Editorial Board Member,

E-mail: marion.nestle@nyu.edu

Editorial

145 r 2011 Macmillan Publishers Ltd. 0197-5897 Journal of Public Health Policy Vol. 32, 2, 143145

You might also like

- Financial Ratio Analysis AssignmentDocument10 pagesFinancial Ratio Analysis Assignmentzain5435467% (3)

- SAP COPA ConfigurationDocument0 pagesSAP COPA ConfigurationDeepak Gupta50% (2)

- Consulting FeesDocument6 pagesConsulting FeesAnanda Raju G100% (1)

- Article 22c Predicting Timing of Marriage Event Using Sudarshana PDFDocument31 pagesArticle 22c Predicting Timing of Marriage Event Using Sudarshana PDFSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Candle BusinessDocument15 pagesCandle BusinessBHAWANI SINGH TANWAR100% (2)

- Qis & MsodDocument16 pagesQis & MsodAdarsh Chhajed50% (2)

- Summary of Salt Sugar Fat: by Michael Moss | Includes AnalysisFrom EverandSummary of Salt Sugar Fat: by Michael Moss | Includes AnalysisNo ratings yet

- TCS Initiating Coverage NoteDocument23 pagesTCS Initiating Coverage NoteinfoetcNo ratings yet

- Bhrigu Chakra With Cycle Rulers Color FinalDocument16 pagesBhrigu Chakra With Cycle Rulers Color FinalLê ThắngNo ratings yet

- Farm To Table - IntroductionDocument8 pagesFarm To Table - IntroductionChelsea Green PublishingNo ratings yet

- Final Marketing PlanDocument33 pagesFinal Marketing Planjai2607100% (3)

- 2001 - Payne & HoltDocument0 pages2001 - Payne & HoltShankesh SinghNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Management NotesDocument37 pagesIntroduction To Management NotesSaurabh Suman100% (2)

- Financial Performance Analysis of Force MotorsDocument89 pagesFinancial Performance Analysis of Force Motorsshaaiily100% (2)

- Chapter 02 - Structure and Synthesis of PFDDocument31 pagesChapter 02 - Structure and Synthesis of PFDcuteyaya24No ratings yet

- Big Food, Food Systems, and Global HealthDocument4 pagesBig Food, Food Systems, and Global HealthSandra MianNo ratings yet

- Declaration en - International Action Day 2012Document16 pagesDeclaration en - International Action Day 2012wftu-pressNo ratings yet

- Kenneth RogoffDocument2 pagesKenneth RogoffSimply Debt SolutionsNo ratings yet

- Towards A Food Revolution 2.2Document33 pagesTowards A Food Revolution 2.2Martin YarnitNo ratings yet

- Food IssuesDocument6 pagesFood Issuesapi-302331557No ratings yet

- Himena Delgado - Food Synthesis Essay SourcesDocument10 pagesHimena Delgado - Food Synthesis Essay SourcesHimena DelgadoNo ratings yet

- Food: EssayDocument4 pagesFood: EssayDerek D LimNo ratings yet

- MGC - Project Proposal - Version1.0Document3 pagesMGC - Project Proposal - Version1.0Alok GoelNo ratings yet

- Capital's Hunger in AbundanceDocument10 pagesCapital's Hunger in AbundanceThavam RatnaNo ratings yet

- McDonald's and Fast Food Industry Impact During PandemicDocument101 pagesMcDonald's and Fast Food Industry Impact During PandemicDream ArchNo ratings yet

- Food Politics Research Paper TopicsDocument7 pagesFood Politics Research Paper Topicsrpmvtcrif100% (1)

- PilzerDocument14 pagesPilzerMonty SainiNo ratings yet

- achristian,+JAFSCD PBFS Keynote Capitalism Holt Gimenez August 2019Document13 pagesachristian,+JAFSCD PBFS Keynote Capitalism Holt Gimenez August 2019Osmar Alejandro Garcia MendivilNo ratings yet

- Global Food SecurityDocument5 pagesGlobal Food SecurityJhomer MandrillaNo ratings yet

- A Food Manifesto For The Future: Mark BittmanDocument3 pagesA Food Manifesto For The Future: Mark BittmanCas CrimNo ratings yet

- Big FoodDocument41 pagesBig FoodaptypoNo ratings yet

- Globalization in Eating HabitsDocument16 pagesGlobalization in Eating Habitsarshia nikithaNo ratings yet

- An Overview of The Industry: Chapter-1Document46 pagesAn Overview of The Industry: Chapter-1Krithi K KNo ratings yet

- Final Copy Should The Food Industry Be Held Responsible For The Obesity and Health Epidemic Ryleigh RoweDocument14 pagesFinal Copy Should The Food Industry Be Held Responsible For The Obesity and Health Epidemic Ryleigh Roweapi-666131119No ratings yet

- Obesity and AgDocument2 pagesObesity and Aghoneyjam89100% (1)

- Big Food, Food Systems, and Global Health: EssayDocument4 pagesBig Food, Food Systems, and Global Health: EssayJohn CitizenNo ratings yet

- Food Security - Food DemocracyDocument5 pagesFood Security - Food DemocracyMorvarid1980No ratings yet

- General Assembly: Report Submitted by The Special Rapporteur On The Right To Food, Olivier de SchutterDocument22 pagesGeneral Assembly: Report Submitted by The Special Rapporteur On The Right To Food, Olivier de SchutterN D Senthil RamNo ratings yet

- Bittman Et Al 2014 PDFDocument5 pagesBittman Et Al 2014 PDFCas CrimNo ratings yet

- WRT 490 Food Justice ManifestoDocument13 pagesWRT 490 Food Justice Manifestoapi-549476760No ratings yet

- Health Campaign KsDocument9 pagesHealth Campaign KsKarma SangayNo ratings yet

- Foresight ReportDocument133 pagesForesight ReportNormandieActuNo ratings yet

- Zero Hunger: Prepared By:-19CE006 Jaineel BhavsarDocument7 pagesZero Hunger: Prepared By:-19CE006 Jaineel BhavsarJaineel BhavsarNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On Hunger in AmericaDocument7 pagesResearch Paper On Hunger in Americaefj02jba100% (1)

- Fourteen Reasons Why Food Security Is ImportantDocument2 pagesFourteen Reasons Why Food Security Is ImportantBanele MngomezuluNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Issues Have Political, Economic, Social, Historic and GeographicDocument3 pagesContemporary Issues Have Political, Economic, Social, Historic and GeographicRadhika RachhadiyaNo ratings yet

- Case 2 7 McDonalds and ObesityDocument4 pagesCase 2 7 McDonalds and ObesityZarlish Khan0% (1)

- The Politics of Hunger: How Supply-Side Solutions Can Lower Food PricesDocument13 pagesThe Politics of Hunger: How Supply-Side Solutions Can Lower Food PricesEddyNo ratings yet

- Public Health Concerns of Food DesertsFDocument9 pagesPublic Health Concerns of Food DesertsFShornai ClaudioNo ratings yet

- Geographical Research, Unit 4: Life On The MarginsDocument22 pagesGeographical Research, Unit 4: Life On The MarginsAlison DeanNo ratings yet

- Win, Win, Win: Core ValuesDocument10 pagesWin, Win, Win: Core ValuesGten UNo ratings yet

- MTR ProjectDocument39 pagesMTR Projectsuresh kumar100% (3)

- Global Food SecurityDocument7 pagesGlobal Food SecurityMizraim EmuslanNo ratings yet

- Food Revolution: Discover How the Way We Produce and Eat Our Food Can Affect the Planet’s Future and People’s HealthFrom EverandFood Revolution: Discover How the Way We Produce and Eat Our Food Can Affect the Planet’s Future and People’s HealthNo ratings yet

- 11.0 PP 73 82 New Foodscapes PDFDocument10 pages11.0 PP 73 82 New Foodscapes PDFroshik rughoonauthNo ratings yet

- Food Security, Food Justice, or Food Sovereignty?: Institute For Food and Development PolicyDocument4 pagesFood Security, Food Justice, or Food Sovereignty?: Institute For Food and Development PolicySridhar SNo ratings yet

- Facing The Future 0Document54 pagesFacing The Future 0Christos VoulgarisNo ratings yet

- Rolling StoreDocument5 pagesRolling StoreYelhsa Gianam AtalpNo ratings yet

- Food System: Submitted By: Abuda, Lance Cedrick B. (BSHM 1-B)Document8 pagesFood System: Submitted By: Abuda, Lance Cedrick B. (BSHM 1-B)alexisNo ratings yet

- Ap Paper 2015 1Document15 pagesAp Paper 2015 1api-298564395No ratings yet

- Fight Against Food Waste and Insecurity With Ugly ProduceDocument4 pagesFight Against Food Waste and Insecurity With Ugly ProduceMehul SinghNo ratings yet

- Equilibrium Effects of Food Labeling PoliciesDocument45 pagesEquilibrium Effects of Food Labeling PoliciesmarcosNo ratings yet

- Food IndustryDocument3 pagesFood Industryneelu999No ratings yet

- Iii. External Analysis: 3.1 General EnvironmentDocument19 pagesIii. External Analysis: 3.1 General EnvironmentBlanche PenesaNo ratings yet

- The World's Expanding Waistline: Diet by Command?Document3 pagesThe World's Expanding Waistline: Diet by Command?KIET DO50% (2)

- Pinpointing The Problem: Stop The Waste: UN Food Agencies Call For Action To Reduce Global HungerDocument1 pagePinpointing The Problem: Stop The Waste: UN Food Agencies Call For Action To Reduce Global HungerAnna NicerioNo ratings yet

- CH 1 Introduction 090215Document20 pagesCH 1 Introduction 090215Denis RibeiroNo ratings yet

- World Food Day SpeechDocument6 pagesWorld Food Day SpeechAbid ShafiqNo ratings yet

- Rising Food Prices Lead to Poverty and HungerDocument4 pagesRising Food Prices Lead to Poverty and Hungersong neeNo ratings yet

- In Securing A Poverty Oriented Commercialization of Livestock Production in The Developing World)Document22 pagesIn Securing A Poverty Oriented Commercialization of Livestock Production in The Developing World)Mariana Girma100% (1)

- Is The Us Responsible For ObesityDocument4 pagesIs The Us Responsible For ObesityManileima SinghaNo ratings yet

- Policy BriefDocument3 pagesPolicy BriefIik PandaranggaNo ratings yet

- Fight Against Food Shortages and Surpluses, The: Perspectives of a PractitionerFrom EverandFight Against Food Shortages and Surpluses, The: Perspectives of a PractitionerNo ratings yet

- Identification FormDocument1 pageIdentification FormSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Varanasi Divn. Tender for Aunrihar Station WorksDocument6 pagesVaranasi Divn. Tender for Aunrihar Station WorksSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Authorization and Identification FormDocument2 pagesAuthorization and Identification FormD-Sign Infotech SevicesNo ratings yet

- 1Document1 page1Sandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- FilexfhbDocument1 pageFilexfhbSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- XEEED Coaching Reasoning Practice Book Download in Hindi PDFDocument120 pagesXEEED Coaching Reasoning Practice Book Download in Hindi PDFpradeep solanki100% (3)

- Up Police 2018BDocument7 pagesUp Police 2018BSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Daily Summary For Radhe Mohan (30082018) 24 Aug - 28 Aug, 2018Document2 pagesDaily Summary For Radhe Mohan (30082018) 24 Aug - 28 Aug, 2018Sandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- 23 Nov - 27 Nov, 2017: Pattern Snapshot For DR Onkar Rai (27112017)Document1 page23 Nov - 27 Nov, 2017: Pattern Snapshot For DR Onkar Rai (27112017)Sandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- It Mid LevelDocument1 pageIt Mid LevelMahesh ThammanaveniNo ratings yet

- CandidateHallTicket PDFDocument2 pagesCandidateHallTicket PDFKil Ler Atti TudeNo ratings yet

- Patient Notes For DR Onkar Rai (27112017) 23 Nov - 27 Nov, 2017Document1 pagePatient Notes For DR Onkar Rai (27112017) 23 Nov - 27 Nov, 2017Sandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Network EngineerDocument1 pageNetwork EngineerDeepak DubeyNo ratings yet

- 5 Jul MeDocument2 pages5 Jul MeDivakar VaidyanathanNo ratings yet

- Install & Run USB Modem on LinuxDocument3 pagesInstall & Run USB Modem on LinuxSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Atul Kumar Tiwari ResumeDocument3 pagesAtul Kumar Tiwari ResumeSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- 23 Nov - 27 Nov, 2017: Pattern Snapshot For DR Onkar Rai (27112017)Document1 page23 Nov - 27 Nov, 2017: Pattern Snapshot For DR Onkar Rai (27112017)Sandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- 21 SharmaDocument5 pages21 SharmaSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- 31 PDFDocument6 pages31 PDFSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- 0 FrontCreditDocument2 pages0 FrontCreditSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Oris Scheme Final 030815Document2 pagesOris Scheme Final 030815Sandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae: Abhishek MishraDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Abhishek MishraSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Name Est City Weighted Score RankDocument1 pageName Est City Weighted Score RankSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- PrabhatDocument6 pagesPrabhatSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

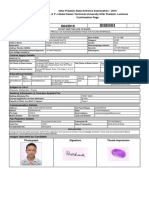

- UPSEE2016 AcknowledgementPage1Document1 pageUPSEE2016 AcknowledgementPage1Sandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Ijtk 3 (2) 162-167Document6 pagesIjtk 3 (2) 162-167Sandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Obesity As Collateral Damage: A Call For Papers On The Obesity EpidemicDocument3 pagesObesity As Collateral Damage: A Call For Papers On The Obesity EpidemicSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

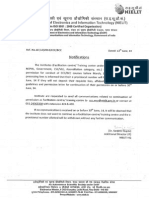

- Withdrawn of Training Facilitation CentreDocument1 pageWithdrawn of Training Facilitation CentreSandeep KumarNo ratings yet

- Midterm Review Term 3 2011 - 2012Document4 pagesMidterm Review Term 3 2011 - 2012Milles ManginsayNo ratings yet

- Tax RemediesDocument19 pagesTax RemediesRocky MarcianoNo ratings yet

- F7int 2013 Dec QDocument9 pagesF7int 2013 Dec Qkumassa kenyaNo ratings yet

- Bank of Punjab Final Balance Sheet AnalysisDocument12 pagesBank of Punjab Final Balance Sheet AnalysisZara SikanderNo ratings yet

- A Case Study On Shouldice HospitalDocument34 pagesA Case Study On Shouldice HospitalSadashivayya SoppimathNo ratings yet

- SSRN Id1456709Document27 pagesSSRN Id1456709Chai LiNo ratings yet

- Reference FormDocument277 pagesReference FormUsiminas_RINo ratings yet

- Liquidity and Asset Management Ratio Analysis for Khind Holding Bhd and Milux Corporation BhdDocument14 pagesLiquidity and Asset Management Ratio Analysis for Khind Holding Bhd and Milux Corporation BhdfuzaaaaaNo ratings yet

- AFSA Assign 1 Enron EditedDocument7 pagesAFSA Assign 1 Enron EditedVarchas BansalNo ratings yet

- Responsibility Accounting, Segment Reporting, and Common Cost AllocationDocument7 pagesResponsibility Accounting, Segment Reporting, and Common Cost AllocationGilbert TiongNo ratings yet

- GMP ContractsDocument3 pagesGMP ContractsHr Ks100% (1)

- CannibalizationDocument10 pagesCannibalizationFarooq AzamNo ratings yet

- Business Plans and Marketing StrategyDocument55 pagesBusiness Plans and Marketing Strategysaachin.dubey1983No ratings yet

- International Transfer Pricing and Subsidiary PerformanceThe Role of Organizational JusticeDocument20 pagesInternational Transfer Pricing and Subsidiary PerformanceThe Role of Organizational JusticeFridRachmanNo ratings yet

- ) Presenting The Contribution As A Group of Assets 2: Does Not Equal Pay Receive Is Not DeterminedDocument20 pages) Presenting The Contribution As A Group of Assets 2: Does Not Equal Pay Receive Is Not Determinedايهاب غزالةNo ratings yet

- Optimized Extraction of Dimension Stone Blocks PDFDocument15 pagesOptimized Extraction of Dimension Stone Blocks PDFLuis Trigueros RamosNo ratings yet

- Ratio Analysis of Mitchals FruitDocument135 pagesRatio Analysis of Mitchals FruitNafeesa Naz50% (2)

- 2 Linear ProgrammingDocument37 pages2 Linear ProgrammingNaveen Gangula0% (1)

- Group Assignment 1 - FinalDocument13 pagesGroup Assignment 1 - FinalWanteen LeeNo ratings yet