Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Legend of Nyami Nyami, River God of the Tonga People

Uploaded by

peter tichiOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Legend of Nyami Nyami, River God of the Tonga People

Uploaded by

peter tichiCopyright:

Available Formats

Shingai Musasiwa, also known as the Nyaminyami (Zambezi River God) or Zambezi Snake

spirit, is one of the most important gods of Tonga people. Nyami Nyami is believed to protect

the Tonga people and give them sustenance in difficult times. The River God is usually portrayed

as female.

Variously described as having the body of a snake and the head of a fish, a whirlpool or a river

dragon, the Nyami Nyami is seen as the god of Zambezi Valley and the river before the creation

of the Kariba Dam. The Nyami Nyami is regularly depicted as a snake-like being or dragon-like

creature with a snake's torso and the head of a fish.

[1]

It can be found as pendants on jewelry,

usually carved out of wood, stone or bone, occasionally ivory, silver or gold both as a fashion

accessory and as a good luck charm similar to the wearing of a St Christopher medallion.

Elaborate traditionally carved walking sticks depicting the Nyami Nyami and its relationship

with the valley's inhabitants were popular with tourists visiting Zambia and have historically

been gifts to prestigious visitors.

It is the traditional role of tribal elders and spirit mediums to intercede on behalf the inhabitants

of the river valley when Nyami Nyami is angered.

The Nyaminyami is said to reside in the Zambezi River and control the life in and on the river.

The spirits of Nyaminyami and his wife residing in the Kariba Gorge are God and Goddess of

the underworld. The Tonga people believe the building of the Kariba Dam deeply offended

Nyami Nyami, separating him from his wife. The regular flooding and many deaths during the

dam's construction were attributed to his wrath. After the Dam was completed the Tonga believe

that Nyami Nyami withdrew from the world of men.

Legend

Although there are several different legends surrounding the Nyaminyami the Kariba legend is

the most documented and widely known fable.

The Kariba Legend

"The BaTonga People lived in the Zambezi Valley for centuries in peaceful seclusion and with

little contact with the outside world. They were simple folk who built their houses in kraal along

the banks of the great river and believed that their gods looked after them supplying them with

water and food.

But their idealistic lifestyle was to be blown apart. In the early 1940s a report was made about

the possibility of a hydro-electric scheme to supply power for the growing industry that

colonialism had brought to the federation of countries that were known as Northern Rhodesia on

one side of the river and Southern Rhodesia on the other, now Zambia and Zimbabwe.

In 1956, construction on the Kariba Dam project was started.

Heavy earth-moving equipment roared into the valley and tore out thousands of hundred-year-

old trees to build roads and settlements to house the workers who poured into the area to build a

dam that would harness the powerful river. The BaTongas peace and solitude was shattered and

they were told to leave their homes and move away from the river to avoid the flood that the dam

would cause.

The name Kariba comes from the word Kariva or karinga, meaning trap, which refers to a rock

jutting out from the gorge where the dam wall was to be built. It was believed by the BaTonga to

be the home of Nyaminyami, the river god, and they believed anyone who ventured near the

rock was dragged down to spend eternity under the water.

Reluctantly they allowed themselves to be resettled higher up the bank, but they believed

Nyaminyami would never allow the dam to be built and eventually, when the project failed, they

would move back to their homes.

In 1957, when the dam was well on its way to completion, Nyaminyami struck. The worst floods

ever known on the Zambezi washed away much of the partly built dam and the heavy equipment,

killing many of the workers.

Some of those killed were white men whose bodies disappeared mysteriously, and after an

extensive search failed to find them, Tonga elders were asked to assist as their tribesmen knew

the river better than anyone. The elders explained Nyaminyami had caused the disaster and in

order to appease his wrath a sacrifice should be made.

They weren't taken seriously, but, in desperation, when relatives of the missing workers were due

to arrive to claim the bodies of their loved ones, the search party agreed in the hope that the

tribesmen would know where the bodies were likely to have been washed to.

A Black calf was slaughtered and floated on the river. The next morning the calf was gone and

the workers bodies were in its place. The disappearance of the calf holds no mystery in the

crocodile infested river, but the reappearance of the workers bodies three days after they had

disappeared has never been satisfactorily explained.

After the disaster, flow patterns of the river were studied to ascertain whether there was a

likelihood of another flood and it was agreed a flood of comparable intensity would only occur

once every thousand years.

The very next rainy season, however, brought further floods even worse than the previous year.

Nyaminyami had struck again, destroying the coffer dam, the access bridge and parts of the main

wall.

The project survived and the great river was eventually controlled. In 1960 the generators were

switched on and have been supplying electricity to Zimbabwe and Zambia ever since.

The BaTonga still live on the shores of Lake Kariba, and many still believe one day Nyaminyami

will fulfill his promise and they will be able to return to their homes on the banks of the river.

They believe Nyaminyami and his wife were separated by the wall across the river, and the

frequent earth tremors felt in the area since the wall was built are caused by the spirit trying to

reach his wife, and one day he will destroy the dam.

You might also like

- Nyami Nyami, God of the ZambeziDocument3 pagesNyami Nyami, God of the ZambeziJohn MedinaNo ratings yet

- Idea of Writing A Novel On The Philippines.: Noli Me TangereDocument12 pagesIdea of Writing A Novel On The Philippines.: Noli Me TangereWency PerezNo ratings yet

- Australian Water StoriesDocument5 pagesAustralian Water Storiesdr_kurs7549No ratings yet

- Environment Reporting: 3rd Place - Ronald Musoke, The IndependentDocument2 pagesEnvironment Reporting: 3rd Place - Ronald Musoke, The IndependentAfrican Centre for Media ExcellenceNo ratings yet

- Nyami Nyami the-WPS OfficeDocument1 pageNyami Nyami the-WPS OfficeMarianne DiosanaNo ratings yet

- Seven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern CityFrom EverandSeven Fallen Feathers: Racism, Death, and Hard Truths in a Northern CityRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (81)

- Term Paper. DocsDocument7 pagesTerm Paper. DocsNOCKSHEDELLE POCONGNo ratings yet

- The Sacred Turtles of KadavuDocument3 pagesThe Sacred Turtles of KadavuSándor TóthNo ratings yet

- Montezuma Castle - A National Monument, ArizonaFrom EverandMontezuma Castle - A National Monument, ArizonaRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Yangtze River Tow MenDocument11 pagesThe Yangtze River Tow MenProbeInternationalNo ratings yet

- Legend of Mainit: Mainit Lake Camiguin IslandDocument2 pagesLegend of Mainit: Mainit Lake Camiguin IslandQueng ElediaNo ratings yet

- Maria CacaoDocument3 pagesMaria CacaoCyra BantilloNo ratings yet

- A Discourse On Phlan and Its ProblemsDocument6 pagesA Discourse On Phlan and Its ProblemsazurecobaltNo ratings yet

- The Legend of RiceDocument6 pagesThe Legend of RiceMargaux Cadag100% (1)

- Angalo & Aran, Cagayan EpicDocument6 pagesAngalo & Aran, Cagayan Epicmaricon elleNo ratings yet

- Unravelling The WanjinasDocument43 pagesUnravelling The WanjinasCelso GarciaNo ratings yet

- The Mountains of The MoonDocument20 pagesThe Mountains of The MoonDAVIDNSBENNETTNo ratings yet

- Alamat NG GuimarasDocument5 pagesAlamat NG GuimarasMonina CahiligNo ratings yet

- Añgalo and Aran, Adam and Eve of The Ilocanos Retold By: Dayao Gladies LDocument9 pagesAñgalo and Aran, Adam and Eve of The Ilocanos Retold By: Dayao Gladies LAntonio, Donna May L.No ratings yet

- Leyenda de La SirenaDocument2 pagesLeyenda de La SirenaYamilet Torres mamaniNo ratings yet

- LegendsDocument8 pagesLegendsPatricia MelendrezNo ratings yet

- Bapâ Rayawan MaidanDocument11 pagesBapâ Rayawan MaidanMary Apple D. CirpoNo ratings yet

- Silverman, "The Sepik River, Papua New Guinea: Nourishing Tradition and Modern Catastrophe"Document37 pagesSilverman, "The Sepik River, Papua New Guinea: Nourishing Tradition and Modern Catastrophe"Eric SilvermanNo ratings yet

- Explorer Magazine Features Kamu LodgeDocument2 pagesExplorer Magazine Features Kamu Lodgenuit_blanche_1No ratings yet

- Legend of MacapunoDocument8 pagesLegend of MacapunoCATHERINE AMANTENo ratings yet

- The Rise and Power of the Lunda Empire in ZambiaDocument4 pagesThe Rise and Power of the Lunda Empire in ZambiaEunice KalandeNo ratings yet

- Lake Tana and Its IslandsDocument19 pagesLake Tana and Its IslandsAbrham DesalegnNo ratings yet

- COLOMBIAN MYTHS ABOUT NATUREDocument9 pagesCOLOMBIAN MYTHS ABOUT NATURElorenaNo ratings yet

- CopyoflakenormanDocument6 pagesCopyoflakenormanapi-241439745No ratings yet

- Consuming Ocean Island: Stories of People and Phosphate from BanabaFrom EverandConsuming Ocean Island: Stories of People and Phosphate from BanabaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- UntitledDocument21 pagesUntitledOswald MtokaleNo ratings yet

- Fil 102 Eko-TulaDocument18 pagesFil 102 Eko-TulaSANCHEZ, CAMILLE JOY CABAYACRUZ.No ratings yet

- Lozi CeremonyDocument8 pagesLozi CeremonyBoris PichlerbuaNo ratings yet

- Subanen HistoryDocument12 pagesSubanen HistoryRomeo Altaire Garcia100% (2)

- Kariba Dam Power & Tourism Hub for Zambia & ZimbabweDocument49 pagesKariba Dam Power & Tourism Hub for Zambia & ZimbabweBharath SpNo ratings yet

- Traditions of The Ancient White PeopleDocument3 pagesTraditions of The Ancient White PeopleUSAssassins0% (1)

- Lake Ronkonkoma in History and Legend, the Princess Curse and Other Stories: a Lifeguard’S ViewFrom EverandLake Ronkonkoma in History and Legend, the Princess Curse and Other Stories: a Lifeguard’S ViewNo ratings yet

- The Origin of The Lake BulusanDocument2 pagesThe Origin of The Lake BulusanFuchigami TakaJenetNo ratings yet

- Jhangara: Book Four of The Lost Books of TalislantaDocument43 pagesJhangara: Book Four of The Lost Books of Talislantaheron61No ratings yet

- Myanmar Traditional BoatsDocument75 pagesMyanmar Traditional BoatsShoon Lae Cho [Mera]No ratings yet

- A River's Gifts: The Mighty Elwha River RebornFrom EverandA River's Gifts: The Mighty Elwha River RebornRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Si Malakas at Si MagandaDocument6 pagesSi Malakas at Si MagandaThess Tecla Zerauc Azodnem100% (2)

- The Legend of Lake ChiniDocument1 pageThe Legend of Lake ChiniAnonymous PjkoibH2No ratings yet

- Avatar Legends The Roleplaying Game 21 30Document10 pagesAvatar Legends The Roleplaying Game 21 30azeazeNo ratings yet

- Acubon SecretsDocument9 pagesAcubon SecretsjasonstierleNo ratings yet

- Gypsy DiversDocument12 pagesGypsy DiversDee SineNo ratings yet

- Related Myths of Eastern SamarDocument2 pagesRelated Myths of Eastern SamarChristine SuarezNo ratings yet

- On Wallace's Track - 1914Document23 pagesOn Wallace's Track - 1914Martin Laverty100% (1)

- The Hungry Coast: Fables from the North Shore of MinnesotaFrom EverandThe Hungry Coast: Fables from the North Shore of MinnesotaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- Jiayukou Village On Great Rock RiverDocument4 pagesJiayukou Village On Great Rock RiverProbeInternationalNo ratings yet

- Accounting Cycle - Explanation, Steps, Example - Accounting For ManagementDocument3 pagesAccounting Cycle - Explanation, Steps, Example - Accounting For Managementpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Bank Reconciliation Statement - Definition, Explanation, Example and Causes of Difference - Accounting For ManagementDocument5 pagesBank Reconciliation Statement - Definition, Explanation, Example and Causes of Difference - Accounting For Managementpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Statement of Cash Flows and The Purpose of Its Preparation - Accounting For ManagementDocument2 pagesStatement of Cash Flows and The Purpose of Its Preparation - Accounting For Managementpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Gayre-The Origin of The Zimbabwean CivilisationDocument263 pagesGayre-The Origin of The Zimbabwean Civilisationpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Thesis Shava GeorgeDocument301 pagesThesis Shava Georgepeter tichi0% (1)

- Minimum Level of Stock - Explanation, Formula, Example - Accounting For ManagementDocument3 pagesMinimum Level of Stock - Explanation, Formula, Example - Accounting For Managementpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Innovations Management PublicationDocument3 pagesInnovations Management Publicationpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Heal ThyselfDocument33 pagesHeal Thyselfpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Experimental and Quasi Experimental and Ex Post Facto Research DesignDocument33 pagesExperimental and Quasi Experimental and Ex Post Facto Research Designpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Revolutionising Functional Textile Printing v1.2Document39 pagesRevolutionising Functional Textile Printing v1.2peter tichiNo ratings yet

- African EducationDocument13 pagesAfrican Educationpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Ubuntu Celebrating The Human Spirit in Contemporary African ArtDocument3 pagesUbuntu Celebrating The Human Spirit in Contemporary African Artpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Real Dynamic Design For Graphic DesignersDocument20 pagesReal Dynamic Design For Graphic Designerspeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Repeating Patterns: Skip To Main ContentDocument3 pagesRepeating Patterns: Skip To Main Contentpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Counterchange OrnamentDocument3 pagesCounterchange Ornamentpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Shona SculptureDocument19 pagesShona Sculpturepeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Ogee and Quatrefoil Designs by Various ArtistsDocument96 pagesOgee and Quatrefoil Designs by Various Artistspeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Good GraphicsDocument3 pagesGood Graphicspeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Livingstone TownDocument4 pagesLivingstone Townpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Digital Textile ReviewDocument2 pagesDigital Textile Reviewpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Colour Accuracy in Digital PrintingDocument8 pagesColour Accuracy in Digital Printingpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Illustrated Architecture Dictionary Illustrated FURNITURE GlossaryDocument5 pagesIllustrated Architecture Dictionary Illustrated FURNITURE Glossarypeter tichiNo ratings yet

- The Digital Designer: How New Technology Impacts Graphic DesignDocument5 pagesThe Digital Designer: How New Technology Impacts Graphic Designpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Sculpture ZimboDocument5 pagesSculpture Zimbopeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Types of Interest GroupsDocument9 pagesTypes of Interest Groupspeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Ancient Yoruba Art Tradition Still Vital TodayDocument13 pagesAncient Yoruba Art Tradition Still Vital Todaypeter tichiNo ratings yet

- The Zambezi River LoongDocument16 pagesThe Zambezi River Loongpeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Poly Logo For PlaneDocument1 pagePoly Logo For Planepeter tichiNo ratings yet

- African ArtistsDocument26 pagesAfrican Artistspeter tichiNo ratings yet

- Journey To The Centre BookDocument32 pagesJourney To The Centre BookLoxx100% (1)

- Ambient Noise Levels in the US Mapped by Station PDFsDocument12 pagesAmbient Noise Levels in the US Mapped by Station PDFsStageof WinangunNo ratings yet

- Earthquake Engineering MCQ PDFDocument16 pagesEarthquake Engineering MCQ PDFHitesh Dhameliya50% (2)

- Structural Design Course Learn ETABS Basics Earthquake AnalysisDocument3 pagesStructural Design Course Learn ETABS Basics Earthquake AnalysisMohammed RafiNo ratings yet

- Daily Warm-Ups FINALDocument123 pagesDaily Warm-Ups FINALbonwar50% (2)

- Recent Advances in Soil Liquefaction Engineering: A Unified and Consistent FrameworkDocument72 pagesRecent Advances in Soil Liquefaction Engineering: A Unified and Consistent FrameworkFederico Piccoli100% (1)

- Example EcDocument55 pagesExample EcRAJENDRA RAUTNo ratings yet

- Bahasa Inggris Kelas 12 Pilihan Ganda PDFDocument6 pagesBahasa Inggris Kelas 12 Pilihan Ganda PDFOrpa melibi MahaNo ratings yet

- Midterm Examination: Disaster Readiness and Risk ReductionDocument3 pagesMidterm Examination: Disaster Readiness and Risk ReductionHarold Nalla Husayan100% (1)

- Updating The Canadian Standards Association Offshore Structures CodeDocument6 pagesUpdating The Canadian Standards Association Offshore Structures CodenabiloucheNo ratings yet

- Passive VoiceDocument19 pagesPassive VoiceIcha ZahraNo ratings yet

- Naskah Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas XII PAKET CDocument5 pagesNaskah Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas XII PAKET CMi CELAK1No ratings yet

- SAP2000 Day 1 Document TitleDocument92 pagesSAP2000 Day 1 Document TitleSudipThapaNo ratings yet

- Structural Inspection Report: Mahanagar Packaging LTDDocument39 pagesStructural Inspection Report: Mahanagar Packaging LTDTahmidur Rahman100% (1)

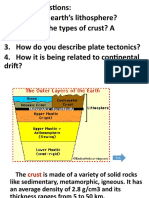

- Science 10 Module 1.1Document34 pagesScience 10 Module 1.1marisNo ratings yet

- Science 6 Q4W1 7 PDFDocument32 pagesScience 6 Q4W1 7 PDFKatrina SalasNo ratings yet

- Application of Dynamic Vibration Absorber (DVA) : Figure Shows Tuned Mass Dampers Beneath The Bridge PlatformDocument3 pagesApplication of Dynamic Vibration Absorber (DVA) : Figure Shows Tuned Mass Dampers Beneath The Bridge PlatformJanice YizingNo ratings yet

- STD Vi 2014 Test Paper With SolutionsDocument12 pagesSTD Vi 2014 Test Paper With SolutionsChiragNo ratings yet

- Thesis Halil SezenDocument357 pagesThesis Halil SezenAhmad Yani100% (1)

- GL 3105: Geomorfologi: 3. Proses Geomorfik EndogenDocument40 pagesGL 3105: Geomorfologi: 3. Proses Geomorfik EndogenGagas Tri LaksonoNo ratings yet

- The Importance of Communication Skills in GeologyDocument4 pagesThe Importance of Communication Skills in Geologyrabwn malikNo ratings yet

- Fema 461Document138 pagesFema 461Kader Newaj Sakib100% (1)

- PR 2Document13 pagesPR 2Harvey HailarNo ratings yet

- Damage Investigation of Girder Bridges Under The Wenchuan Earthquake and Corresponding Seismic Design RecommendationsDocument8 pagesDamage Investigation of Girder Bridges Under The Wenchuan Earthquake and Corresponding Seismic Design RecommendationsfanfengliNo ratings yet

- Earthquake Resistant Design of Buildings 2020: A Comparative Study of Old and Revised Provisions in Indian Seismic CodesDocument14 pagesEarthquake Resistant Design of Buildings 2020: A Comparative Study of Old and Revised Provisions in Indian Seismic CodesFazilat Mohammad ZaidiNo ratings yet

- PCI Bridge ManualDocument34 pagesPCI Bridge ManualEm MarNo ratings yet

- Sase Structural Design Report Rev00Document21 pagesSase Structural Design Report Rev00SerkanAydoğduNo ratings yet

- Bridge ConstructionDocument33 pagesBridge ConstructionVivekChaudhary100% (3)

- Assignment: 1999 Cherry Hills Subdivision Landslide 2006 Southern Leyte Mudslide Date & LocationDocument10 pagesAssignment: 1999 Cherry Hills Subdivision Landslide 2006 Southern Leyte Mudslide Date & LocationClint Ulangkaya LopezNo ratings yet

- SEISMIC PERFORMANCE OF BRACE CONNECTIONSDocument13 pagesSEISMIC PERFORMANCE OF BRACE CONNECTIONSAlexander BrennanNo ratings yet