Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jar20092 6 PDF

Uploaded by

Saray MoraOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jar20092 6 PDF

Uploaded by

Saray MoraCopyright:

Available Formats

The Efficacy of Brand-Execution Tactics in TV Advertising, Brand Placements, and Internet

Advertising

Jenni Romaniuk

Ehrenberg-Bass Institute for Marketing Science, University of South Australia

INTRODUCTION

Across all theories of advertising, there is a consistent theme: For the exposure to have any consequent effect in the future, the viewer

needs to know which brand is being advertised. It is crucial, therefore, for viewers of an advertisement to register the brand name in their

memory as a part of their exposure to that advertisement. The key mechanism for communicating the brand is direct branding execution,

which is how the brand name is presented throughout an advertisement. This execution (the focus of this article) consists of an

advertisement's mode, its timing, and its structureall of which can help a brand name cut through other media clutter and be noticed by

viewers.

Despite this acknowledged importance, evidence abounds that the branding execution often fails to capture the viewers' attention, even if

they notice an advertisement's creative content. Correct brand identification from viewers with verified advertisement exposure is about 40

percent (Franzen, 1994; Rossiter and Bellman, 2005). In other words, more than half of those who remember seeing an advertisement fail

to register the brand name and that a considerable amount of advertising exposures are wasted due to ineffective branding execution.

Ineffective branding execution occurs when the presentation of a brand name within an advertisement is insufficient in getting the brand

name itself noticed. The viewer either does not remember any brand at all, or cites a competing brand.

Why Single Out Branding Execution?

Branding is the only element of the advertisement that is not optional. It is what differentiates the creative piece as an advertisement,

rather than a short movie. Consumers can rarely act immediately on their advertising exposure. For at least a period of time, therefore,

the advertisement needs to appropriately register some sort of brand identity in buyer memory to ensure that traces of it can be recalled

in a buying situation.

Topic Relevance

Audience fragmentation means that marketers may need to spend more to reach different pockets of potential consumers in order to reach

a wide audience. Advertisers need to maximize the chance of sales effectiveness from every exposure. This fragmentation is driven by the

presence of new media (the internet, social networking, word of mouth) as well as alternative mechanisms in old media (i.e., brand

placements within TV programs).

This article has two primary objectives:

G To bring together the knowledge of the impact of branding execution on advertising effectiveness in order to identify the empirically

generalized findings.

G To compare traditional and new media in their performance on these execution tactics in order to identify key areas for

improvement across both new and old media.

BRANDING EXECUTION EFFECTIVENESS: CURRENT EMPIRICAL GENERALIZATIONS

This article focuses on quantifiable, objective measures of branding execution, not subjective metrics such as the brand's role in creative-

concept development. With a strict emphasis on empirical generalizations, the research focuses on execution elements that have been

investigated in multiple studies. Specifically:

G Visual frequency: How many times is the brand visually represented?

G Verbal frequency: How many times is the brand mentioned?

G Total brand exposures: How often is the brand referenced, regardless of mode?

G Duration of brand: For what period of time is the brand in front of the viewer?

G Early branding: Does the brand appear early in the advertisement?

G Dual mode: Does the advertisement include both visual and verbal branding-execution elements?

Journal of Advertising Research

Volume 49, No. 2, June 2009

www.journalofadvertisingresearch.com

This research includes both paid-media television advertising as well as brand placement within programming. Although there has been

some research into how brand placement performs in the context of movies, TV is the medium that has been the primary focus of research

into branding execution. Empirical generalizations are drawn when there is either consistency across the studies conducted to date, or

when the vast weight of evidence favors a particular finding.

The report's two primary dependent variables are:

G Brand recall: Can someone remember the brand advertising?

G Advertising persuasion: Did the advertisement increase the likelihood of the viewer buying the brand?

The discussion is focused on the relationship between brand-execution tactics and these two advertising-exposure outcomes.

EXECUTION ELEMENTS

Visual Frequency

The evidence for the influence of visual frequency on recall is strong (Romaniuk, 2008 [2 studies]; Scott and Craig-Lees, 2006; Stewart

and Furse, 1986). The empirical result is generalized across pretest and experimental situations as well as forced exposure and natural

viewing environments (see Table 1). There are two studies that did not find a positive relationship.

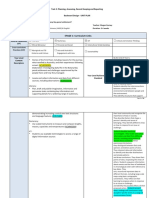

Table 1: Visual Frequency

In contrast, there is little evidence to support that visual frequency has a positive relationship with persuasion, with no relationship found

for the two studies conducted to date (Stewart and Furse, 1986; Stewart and Koslow, 1989).

EGla: Visual brand frequency is related to recall.

EGlb: Visual brand frequency is not linked to advertising persuasion.

Verbal Frequency

Three studies using pretest samples (Stewart and Furse, 1986; Stewart and Koslow, 1989; Walker and von Gonten, 1989) show a positive

link between verbal frequency and recall of the brand (see Table 2), as does the one study in brand placement (Romaniuk and Lock,

2008). The advertising studies drawing from samples watching television in their natural viewing environment, however, do not show a

positive relationship between verbal branding frequency and brand recall (Romaniuk, 2008 [2 studies]). This suggests that verbal

frequency may be effective in helping the brand cut through during a pretest, but is unable to cut through in an environment such as the

family home. There is, again, no link with persuasion in the two studies conducted to date. The weakness with the research to date,

therefore, is that it holds only in pretest environments. This makes it difficult to claim an empirically generalized result from studies to date.

And there is no empirically generalized result for the relationship between verbal frequency and recall.

Table 2: Verbal Frequency

EG2: Verbal brand frequency is not linked to advertising persuasion.

Total Frequency

There is a consistent empirical generalization that the frequency with which the brand occurs is related to advertising/brand recall across

the five studies (see Table 3) (Romaniuk, 2008 [2 studies]; Romaniuk and Lock, 2008; Stanton and Burke, 1998 [2 studies]). This

relationship has held in three different advertising exposure environments: home natural viewing environments, experimental in-home

viewing, and pretests. It has also held over studies including both 15- and 30-s advertisement lengths and for both brand placements and

advertising. In two recent studies, however, the relationship between total frequency and brand recall was weaker than the relationship

between visual frequency and brand recall (Romaniuk, 2008 [2 studies]). Further testing, therefore, is needed to determine the value of

saying the brand name over showing it visually.

Table 3: Total Brand Frequency

Again, there is very little evidence of any relationship with persuasion in three of the four studies (Stanton and Burke, 1998 [2 studies];

Stewart and Furse, 1986; Stewart and Koslow, 1989).

EG3a: There is a positive relationship between the total frequency of brand occurrences and recall, but this needs further testing to

separate out visual frequency effects.

EG3b: There is no relationship between total frequency of brand occurrences and advertising persuasion.

Duration

In most studies (see Table 4), there is no observed relationship between duration and recall in pretest, experimental, and real-world

conditions. The one exceptionin which a brand placement that lasted more than 10 s was associated positively with brand recall

(Romaniuk and Lock, 2008). There is no relationship with persuasion across the two studies that have tested for this.

Table 4: Dual Mode

EG4a: There is no relationship between the duration of branding and recall.

EG4b: There is no relationship between the duration of branding and advertising persuasion.

Early Branding

The weight of evidence favors early branding, with five out of eight studies showing a positive relationship between early branding and

recall (see Table 5). There was no evidence in three of four studies that early branding is linked to higher persuasion, the exception being

30-s executions cited in Stanton and Burke (1998).

Table 5: Early Branding

Conclusion

EG5a: There is a positive relationship between early presence of the brand and recall.

EG5b: There is no relationship between early presence of the brand and advertising persuasion.

Dual Mode

All five studies that have tested the impact of dual mode (visual and verbal branding) have found it to be more effective in stimulating

recall than single-mode execution (see Table 6). This empirical generalization holds in forced and natural-viewing environments,

experimental designs, and pretests. It also generalizes across advertisements and placements. No tests of the relationship between dual-

mode execution and persuasion could be found.

Table 6: Duration

Conclusion

EG6: There is a positive relationship between dual mode branding execution and recall.

OVERALL SUMMARY

There is more to branding than simply showing the brand, so it is not surprising that there is not 100 percent consistency across studies for

any execution elements. There often was, however, overwhelming evidence in a particular direction. One generalization across all studies

was the finding that branding execution is not linked to persuasion. In hindsight, this is probably not surprising, given the primary role that

branding execution plays in identifying the brand. The consistency of these results across all execution elements suggests that we should

not expect our branding execution to persuade viewers.

Two studies stood out with some results that were out of sync with the other studies. Consistent in both was the conversion of independent

variables from continuous to dichotomous in structure

(Romaniuk and Lock, 2008; Stanton and Burke, 1998). This condition requires establishment of a cut-off pointa decision that may lead to

lost information and, therefore, make the variable less sensitive. The introduction of a cut-off point may explain the contradictory findings,

but more research is needed to test why the two studies produced different results.

EXAMINING CURRENT PRACTICE

We now document the branding execution from approximately 1,500 U.S. primetime television advertisements, 2,000 U.S. television

program placements, and 100 video-based internet advertisements (see Table 7). To be considered comparable to television advertising

and brand placements, internet advertisements were chosen that had to have a moving component within the advertisement. In all cases,

multiple coders coded execution elements.

Table 7: Current Brand Execution Practice across Media

The TV spots and placements came from U.S. prime-time TV in 2006, and the internet advertisements were accessed in 2008. Results are

shown by execution element across product categories. The television advertisements were 15 and 30 s in length only, with the exception

of television-program promotions, which ranged from 5 to 60 s.

The brand placements were in shows that were predominantly 30 or 60 min in length and multiple brand placements for the same brand

within the same show were combined to represent a single brand placement.

The internet advertisements ranged from 5 to 150 s. In the case of continuously looping advertisements, a point that represented the start

of the message was taken as the start of the advertisement.

DISCUSSION

This article shows that there is empirically generalizable knowledge in the area of branding execution. Importantly, some execution tactics

are more effective than others. This knowledge may help move marketers out of a more branding toward an understanding of what

makes for better branding. There is strong evidence to support:

G visual brand frequency;

G early brand presence;

G dual-mode branding.

Particularly in real-world settings, there is mixed evidence regarding verbal frequency and, by extension, total frequency. There is very

little evidence to support duration as an effective execution strategymore branding does not mean more effective branding. Importantly,

there is a consistency across all studies in the effects of branding executionmore specifically, that it works more effectively on brand

memories, rather than persuasion.

An examination of current practice revealed that a large number of current television advertisements did not exhibit best practice in

terms of these branding principles. It also highlights that new media are not using this knowledge and, therefore, are making the same

kind of execution mistakes. These failings point to the potential for gains to be made in advertising effectiveness if more advertisers knew

aboutand implementedthe empirical generalizations about branding execution that already exist.

FUTURE RESEARCH AGENDA

Based on the findings to date, and marketing practice, the key priorities for research are as follows:

G More studies devoted to branding execution as a stand-alone element with the objective of making the brand name salient. A

separate stream of research would encourage researchers to focus specifically on what drives effective branding executionan

examination that purposefully would avoid the distraction of other advertising creative elements.

G More real-world studies. Most of the work to date has been in forced-exposure environments, either under pretest conditions or in

experimental design. Knowing what we do about advertising avoidance (Paech, Riebe, and Sharp, 2003) and passive viewing of

television (Krugman, Cameron, and White, 1995), real-world studies that take into account these viewer-related factors could help

develop robust empirical generalizations. It is important to ensure we take into account that the processing of advertising involves

both the characteristics of advertising and the viewing environment. Studies should incorporate the viewing environment, therefore,

and allow for the consideration of advertising-avoidance behavior.

G Clearer quantification of results. Most studies report effects, but do not clearly quantify the results, making it difficult to establish

quantifiable benchmarks that can become guidelines for advertising practice. For example, future research would be served

quantifying the effects of each visual exposure and examining the conditions that produced more positive results. Further,

understanding the nature of the relationship with continuous variables is important when identifying norms for practice. Knowing if

the relationship is linear or curvilinear is important. And, in the case of a curve, it is important to identify the opportunities for

maximum gains and the points where diminishing returns begin.

G Studies into the effects of branding execution within internet advertisements are needed to see if the same findings hold in this

medium. The consumption of internet advertising is different from TV: it tends to be a more focused activity, but it also takes place

in a cluttered page-viewing environment that is very different from television. Further research needs to identify what characteristics

can help ensure that the brand name breaks through this clutter.

G Studies into other forms of branding, such as the use of distinctive elements (taglines, logos, symbols, celebrities, etc.) to identify

the brand name. Research is needed to identify the extent to which these elements can replace direct branding execution. The best

use of these elements in different media is yet important area for future research.

Given the documented deficits in the current practice in brand execution, it seems that there is considerable scope for better branding in

advertising.

EMPIRICAL GENERALIZATION

The number of times a brand visually appears in a video advertisement is correlated with higher correct identification of that brand within

the advertisement.

Jenni Romaniuk, an associate professor at the University of South Australia, heads the Brand Equity Research Group at the Ehrenberg-

Bass Institute for Marketing Science. Her areas of expertise are brand equity tracking, brand salience, advertising effectiveness, and word

of mouth.

Jenni@MarketingScience.info

REFERENCES

Brennan, Ian, and Laurie A. Babin. Brand Placement Recognition: The Influence of Presentation Mode and Brand Familiarity. In Handbook

of Product Placement in the Mass Media, Mary-Lou Galacian, ed. Hawthorne, NJ: The Hawthorne Press, Inc., 2004.

Fazio, Russell H., Paul M. Herr, and Martha C. Powell. On the Development and Strength of Category-Brand Associations in Memory: The Case of Mystery Ads.

Journal of Consumer Psychology 1, 1 (1992): 113.

Franzen, G. Advertising Effectiveness: Findings from Empirical Research. Henley-on-Thames, U.K.: NTC Publications, 1994.

Gupta, Pola B., and Kenneth R. Lord. Product Placement in Movies: The Effect of Prominence and Mode on Audience Recall. Journal of

Current Issues and Research in Advertising 20, 1 (1998): 4759.

Krugman, Dean M., Glen T. Cameron, and Candace McKearney White. Visual Attention to Programming and Commercials: The Use of In-

Home Observations. Journal of Advertising 24, 1 (1995): 112.

Law, Sharmistha, And Kathryn A. Braun. I'll Have What She's Having: Gauging the Impact of Product Placements on Viewers. Psychology and Marketing 17, 12

(2000): 105975.

Paech, Samantha, Erica Riebe, and Byron Sharp. What Do People Do in Advertisement Breaks? Australia and New Zealand Marketing

Academy Conference. Adelaide: University of South Australia, 2003.

Romaniuk, Jenni. The Effectiveness of Branding Execution Tactics within Television Advertisements. Ehrenberg-Bass Institute Working

Paper, 2008.

Romaniuk, Jenni, and Craig Lock. The Recall of Brand Placements with Television Shows. Ehrenberg-Bass Institute Working Paper, 2008.

Rossiter, John R., and Steven Bellman. Marketing Communications: Theory and Applications. Frenchs Forest, U.K.: Pearson Education,

2005.

Scott, Jane, and Margaret Craig-Lees. Optimizing Success: Product Placement Quality and Its Effect on Recall. In In-Film Advertising:

Brand Positioning Strategy, P. Kanchan, ed. India: IC-FAI Business School, 2006.

Stanton, John L., and Jeffrey Burke. Comparative Effectiveness of Executional Elements in TV Advertising 15 versus 30 Second

Commercials. Journal of Advertising Research 38, 6 (1998): 713.

Stewart, David W., and David H. Furse. Effective Television Advertising: A Study of 1000 Commercials. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books,

1986.

, and S. Koslow. Executional Factors and Advertising Effectiveness: A Replication. Journal of Advertising 18, 3 (1989): 2132.

Stout, Patricia A., and Benedicta L. Burda. Zipped Commercials: Are They Effective? Journal of Advertising 18, 4 (1989): 2332.

Walker, David, and Michael F. von Gonten. Explaining Related Recall Outcomes: New Answers from a Better Model. Journal of Advertising

Research 29, 3 (1989): 1121.

Copyright Advertising Research Foundation 2009

Advertising Research Foundation

432 Park Avenue South, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10016

Tel: +1 (212) 751-5656, Fax: +1 (212) 319-5265

www.warc.com

All rights reserved including database rights. This electronic file is for the personal use of authorised users based at the subscribing

company's office location. It may not be reproduced, posted on intranets, extranets or the internet, e-mailed, archived or shared

electronically either within the purchasers organisation or externally without express written permission from World Advertising Research

Center.

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Business Studies in Action H SC 6 eDocument597 pagesBusiness Studies in Action H SC 6 eDEK Games100% (1)

- Exploring Global Languaje and Business Skills Acquisition in Multicultural LearningDocument6 pagesExploring Global Languaje and Business Skills Acquisition in Multicultural LearningJorge VillarrealNo ratings yet

- Task 3Document18 pagesTask 3api-335506637No ratings yet

- Ethical Hacking Certification Training CourseDocument8 pagesEthical Hacking Certification Training CourseHadiya SarwathNo ratings yet

- Hawkes ctp2 Eist Clevr 22-23Document3 pagesHawkes ctp2 Eist Clevr 22-23api-640193182No ratings yet

- Muhamad Sham Shahkat Ali, PHDDocument24 pagesMuhamad Sham Shahkat Ali, PHDNazila AdipNo ratings yet

- Session 3: Planning The AssessmentDocument27 pagesSession 3: Planning The AssessmentSHYRYLL ABADNo ratings yet

- Effective Teaching CommerceDocument7 pagesEffective Teaching CommerceTalent MuparuriNo ratings yet

- Literary ContextDocument5 pagesLiterary ContextAlthea Kenz Cacal DelosoNo ratings yet

- Writing TopicsDocument4 pagesWriting Topicshongpk.2006No ratings yet

- Seton Hill University Daily Lesson Plan For Student TeachersDocument2 pagesSeton Hill University Daily Lesson Plan For Student Teachersapi-280008473No ratings yet

- Principles of Task-Based Language TeachingDocument12 pagesPrinciples of Task-Based Language TeachingBalqis SephiaNo ratings yet

- 6th Grade Math Curriculum Guide-Unit I-Four OperationsDocument2 pages6th Grade Math Curriculum Guide-Unit I-Four Operationsapi-263833433No ratings yet

- Google Search Quality Evaluator GuidelinesDocument160 pagesGoogle Search Quality Evaluator GuidelinesChristine BrimNo ratings yet

- KPMG Prodegree EBrochureDocument6 pagesKPMG Prodegree EBrochurerajiv559No ratings yet

- Houseparty Powerpoint - Edt 180 Fall 2019 1Document15 pagesHouseparty Powerpoint - Edt 180 Fall 2019 1api-485159671No ratings yet

- Lesson 6: Communication and GlobalizationDocument3 pagesLesson 6: Communication and GlobalizationKier Arven Sally100% (1)

- Broadcasting in Times of CrisisDocument2 pagesBroadcasting in Times of Crisismfilipo1964No ratings yet

- Evolution of Traditional To A New MediaDocument27 pagesEvolution of Traditional To A New MediaFe Lanny L. TejanoNo ratings yet

- Data Pernyataan Tahap Penguasaan Bahasa Inggeris Tingkatan T1 2019 Kemahiran TP TafsiranDocument4 pagesData Pernyataan Tahap Penguasaan Bahasa Inggeris Tingkatan T1 2019 Kemahiran TP Tafsiranamsy1224No ratings yet

- Communication Skills For Professionals UNIT 1 PDFDocument102 pagesCommunication Skills For Professionals UNIT 1 PDFpranavNo ratings yet

- Lecture 1 B. Reading and ComprehensionDocument20 pagesLecture 1 B. Reading and ComprehensionConcerned CitizenNo ratings yet

- Rubric For Peer & Self EvaluationDocument2 pagesRubric For Peer & Self EvaluationJELENE DAEPNo ratings yet

- Ccna 4: Wan Technologies: Cisco Networking Academy ProgramDocument9 pagesCcna 4: Wan Technologies: Cisco Networking Academy ProgramEzzyOrwobaNo ratings yet

- The Informal System and The "Hidden Curriculum"Document24 pagesThe Informal System and The "Hidden Curriculum"Siti Zanariah TaraziNo ratings yet

- OTP SMS in UAE & Saudi Arabia - Transactional SMS ServiceDocument5 pagesOTP SMS in UAE & Saudi Arabia - Transactional SMS ServiceinayagillnidaNo ratings yet

- National College of Business and The Arts - Cubao Department of AccountancyDocument4 pagesNational College of Business and The Arts - Cubao Department of AccountancyClint-Daniel AbenojaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To The Promotional MixDocument2 pagesIntroduction To The Promotional MixNaveen ByndoorNo ratings yet

- Narrative Activities For The Language Classroom - by Ruth WajnrybDocument6 pagesNarrative Activities For The Language Classroom - by Ruth WajnrybFabián CarlevaroNo ratings yet

- Giai Thich Cambridge Ielts 13 Test 1 Passage 1 by Ielts NgocbachDocument7 pagesGiai Thich Cambridge Ielts 13 Test 1 Passage 1 by Ielts NgocbachthanhNo ratings yet