Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sunhillo - Steve UAS Article Feb 2014

Uploaded by

monel_246710 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views3 pagesArticle about a NJ Guardsman & the Drone company he works for.

Original Title

Sunhillo_Steve UAS Article Feb 2014

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentArticle about a NJ Guardsman & the Drone company he works for.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

14 views3 pagesSunhillo - Steve UAS Article Feb 2014

Uploaded by

monel_24671Article about a NJ Guardsman & the Drone company he works for.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

South Jersey officer-turned-

businessman is key to drone research

Steve Iaquinto Jr. is Sunhillo Corp.'s director of operations and program management. "I'm seeing through what I started" as an Army

National Guard captain in Afghanistan, he says. (ELIZABETH ROBERTSON / Staff Photographer)

POSTED: JANUARY 28, 2014

WEST BERLIN, N.J. - Qari Nazar Gul was an elusive target. The top-level Taliban commander

rarely left Pakistan for operations in Afghanistan. He dispatched couriers and ordered attacks

from afar.

Gul knew there was an eye in the sky and did not want to take a chance. In 2010, the eye

belonged to Capt. Steve Iaquinto Jr., a targeting officer in charge of four aerial drones that

searched for Taliban fighters in four provinces north of Kabul.

The New Jersey Army National Guard officer collected intelligence on enemy activities, then

planned combat ground operations that resulted in a half-dozen kills and more than 30 arrests,

including that of Gul's nephew.

Three years later, the wily Taliban commander is still being sought, and Iaquinto is still working

with drones - or unmanned aerial systems (UAS) - this time in the civilian world with a far

different mission that could give the economy a shot in the arm.

"I'm seeing through what I started," said Iaquinto, 44, of Winslow Township, who was awarded

the Bronze Star for his service in Afghanistan. New UAS uses will take the technology "to the

next level."

His company, Sunhillo Corp., in West Berlin, has worked with Virginia Polytechnic Institute and

State University, and local schools including Rutgers University and Richard Stockton College,

to safely integrate UASes into the national airspace for peaceful uses.

The unmanned aircraft can inexpensively stay aloft for hours, making them a possible future tool

to perform search-and-rescue missions and topographical mapping, analyze flood or storm

damage, and monitor crops, livestock, forest fires, and climate change. Amazon has even

considered using them to deliver packages. The safety features and regulations governing UAS

uses still have to be worked out.

"This means jobs," said Iaquinto, Sunhillo's director of operations and program management.

"We want to be part of that.

"You need qualified operators that we call pilots," he said. "You need mechanics, facility

managers, and aviation facilities."

Many of the best, Iaquinto said, are already in New Jersey. The New Jersey National Guard and

Reserve "has qualified people right now," he said. "Why not leverage this huge pool of

experience?"

The Federal Aviation Administration last month approved a joint application by New Jersey and

Virginia to be among six national UAS test sites. Others will be in New York, Nevada, North

Dakota, Texas, and a joint region encompassing Alaska, Hawaii, and Oregon.

Researchers at those sites - the first will open in less than six months - will develop "sense-and-

avoid" systems to prevent collisions and lost-link procedures that will help the FAA write

regulations for future commercial and civil uses of the unmanned craft.

The local beginnings of the new unmanned aircraft program were planted in the summer 2009,

when Iaquinto, then the National Guard's deputy director of intelligence, was assigned to conduct

a "proof of concept" mission to demonstrate UAS capabilities.

Their test was performed over the Warren Grove Range in Ocean County, north of the Atlantic

City Airport and William J. Hughes FAA Technical Center. For six months, a team of military

UAS operators who had served in Iraq flew dozens of missions from a small airstrip.

The remote area in Little Egg Harbor, Stafford, and Barnegat Townships is now routinely used

by the New Jersey National Guard's UAS platoon and will be used in the new civilian program

along with unused airspace over the Atlantic as the new UAS program gets underway.

The 2009 mission "led to us opening discussions with the FAA about the potential to fly outside

the restricted area of the Warren Grove Range and into national airspace," Iaquinto said. "The

FAA was just beginning to develop their UAS program."

The drones do not carry munitions and will have safety features such as a parachute that will

deploy if power is lost, said Iaquinto, who left the Guard for Sunhillo in 2012.

"The UAS can't leave the restricted airspace or point surveillance equipment outside of that

zone," he said about the testing period at Warren Grove, seeking to quell public concerns about

spying and privacy. "I believe it is important to separate the platform from the payload.

"People hear 'drones' in American airspace and immediately think intelligence collection on U.S.

citizens from government," he said. "As a U.S. citizen, civilian, and former military intelligence

officer, I strongly disagree with anyone willing to compromise our civil liberties as Americans."

UASes and spying concerns were the topic last year of U.S. Senate Judiciary Committee

hearings. "The increased use of drones to conduct surveillance in the United States must be

accompanied by increased privacy protections," said Amie Stepanovich, director of the Domestic

Surveillance Project at the Electronic Privacy Information Center. "The current state of the law is

insufficient to address the drone surveillance threat."

Five years after the Warren Grove test, the FAA sought bids for the six UAS test sites, one of

which went to the Mid-Atlantic Aviation Partnership (MAAP), which includes Virginia Tech

and Iaquinto's firm.

Virginia Tech is already flying UASes but must get a certification of authorization each time to

fly in a specific location during a specific time, said Jon Greene, MAAP's acting executive

director and associate director of the school's Institute for Critical Technology and Applied

Science.

Sunhillo will provide trained personnel, equipment, and research and development. "There is

much work to be done," Iaquinto said. "But I can see so many exciting opportunities for our local

development surrounding the UAS program and its countless commercial applications."

ecolimore@phillynews.com

856-779-3833 InkyEBC

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Dragon Harvest - GM BinderDocument7 pagesDragon Harvest - GM Bindermonel_24671No ratings yet

- The Magic DumpDocument68 pagesThe Magic Dumpmonel_24671100% (1)

- Test Considerations of 5GDocument9 pagesTest Considerations of 5Gmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Test Considerations of 5GDocument9 pagesTest Considerations of 5Gmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Test Considerations of 5GDocument9 pagesTest Considerations of 5Gmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Predator XP SATCOM Data Link - SS - WEBDocument2 pagesPredator XP SATCOM Data Link - SS - WEBOrshanetzNo ratings yet

- How To Search Mail in Gmail With Search OperatorsDocument15 pagesHow To Search Mail in Gmail With Search Operatorsmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Nokia Motive Service Management PlatformDocument4 pagesNokia Motive Service Management Platformmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Potion Taste ChartDocument4 pagesPotion Taste Chartmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Wi Fi Poster TextronixDocument2 pagesWi Fi Poster TextronixenergiculNo ratings yet

- Spell Name Metamagic Effect Metamagic Component Minimum CostDocument14 pagesSpell Name Metamagic Effect Metamagic Component Minimum Costmonel_24671No ratings yet

- LG Urbane User GuideDocument70 pagesLG Urbane User Guidemonel_24671No ratings yet

- 3GPP Release 16 WP LTR WRDocument5 pages3GPP Release 16 WP LTR WRJurassiclark100% (1)

- How Secure Is Employment at Older Ages 2Document30 pagesHow Secure Is Employment at Older Ages 2monel_24671No ratings yet

- DND 3.5 - Practical Guide To FamiliarsDocument19 pagesDND 3.5 - Practical Guide To Familiarsmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Force Missile MageDocument2 pagesForce Missile Magemonel_24671No ratings yet

- The History and Future of Wi Fi Po en 3609 6206 82 v0101Document1 pageThe History and Future of Wi Fi Po en 3609 6206 82 v0101monel_24671No ratings yet

- DND 3.5 - Sorcerer Wizard Supremacy Caster Spell ListDocument10 pagesDND 3.5 - Sorcerer Wizard Supremacy Caster Spell Listmonel_24671No ratings yet

- The History and Future of Wi Fi Po en 3609 6206 82 v0101Document1 pageThe History and Future of Wi Fi Po en 3609 6206 82 v0101monel_24671No ratings yet

- DND 3.5 - Practical Guide To MetamagicDocument4 pagesDND 3.5 - Practical Guide To Metamagicmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Axon Body 3 User ManualDocument44 pagesAxon Body 3 User Manualmonel_24671No ratings yet

- 1MA286 2e AntArrTest 5GDocument30 pages1MA286 2e AntArrTest 5GSatadal GuptaNo ratings yet

- How Secure Is Employment at Older Ages 2Document30 pagesHow Secure Is Employment at Older Ages 2monel_24671No ratings yet

- Wi Fi Poster TextronixDocument2 pagesWi Fi Poster TextronixenergiculNo ratings yet

- Keysight - First Steps in 5G PDFDocument9 pagesKeysight - First Steps in 5G PDFpravin.netalkar2353No ratings yet

- How To Search Mail in Gmail With Search OperatorsDocument15 pagesHow To Search Mail in Gmail With Search Operatorsmonel_24671No ratings yet

- Radio Fundamentals For Cellular NetworksDocument40 pagesRadio Fundamentals For Cellular Networksmonel_24671100% (1)

- LG Urbane User GuideDocument70 pagesLG Urbane User Guidemonel_24671No ratings yet

- 3GPP Release 16 WP LTR WRDocument5 pages3GPP Release 16 WP LTR WRJurassiclark100% (1)

- LTE LBS White PaperDocument23 pagesLTE LBS White PaperMohamad AmmarNo ratings yet

- ST IQ Wis DX Con CH: Low High 7-High High High HighDocument2 pagesST IQ Wis DX Con CH: Low High 7-High High High Highmonel_24671No ratings yet

- KHMA Catalogue 02 ChangesDocument14 pagesKHMA Catalogue 02 ChangesnetobviousNo ratings yet

- University of Adelaide Micro Air Vehicle Final ReportDocument186 pagesUniversity of Adelaide Micro Air Vehicle Final Reportbinho58No ratings yet

- Assymetric DefenceDocument4 pagesAssymetric DefenceMiguel Angel Ruiz RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Výrobné Schopnosti ZBOP AJ2Document20 pagesVýrobné Schopnosti ZBOP AJ2Irin200No ratings yet

- E VTLODocument2 pagesE VTLOJose Ramon Anaya AlvarezNo ratings yet

- Easa Ai Roadmap 2 0 2023Document36 pagesEasa Ai Roadmap 2 0 2023Merih Alphan KaradenizNo ratings yet

- 144 2021 ND-CP 520986Document80 pages144 2021 ND-CP 520986Kim LeNo ratings yet

- Compendium of 75 Agri EntrerenuerDocument190 pagesCompendium of 75 Agri EntrerenuerAbhishek GhoshNo ratings yet

- Design and Static Structural Analysis of A QuadcopterDocument4 pagesDesign and Static Structural Analysis of A QuadcopterMohammed Ali Al-shaleliNo ratings yet

- Object Detection Using Image ProcessingDocument7 pagesObject Detection Using Image ProcessingtotolNo ratings yet

- Final Report Catia Uav 1Document32 pagesFinal Report Catia Uav 1farisilmie123No ratings yet

- Consumer Iot: Security Vulnerability Case Studies and SolutionsDocument6 pagesConsumer Iot: Security Vulnerability Case Studies and SolutionsAhmed Mahamed Mustafa GomaaNo ratings yet

- Syed Ammal Engineering College Electrical Machines LabDocument7 pagesSyed Ammal Engineering College Electrical Machines LabDhivya BNo ratings yet

- Vidius Manual v2Document1 pageVidius Manual v2ManuelNo ratings yet

- SkyViper StreamingVideo Spider-Drone Instructions PDFDocument2 pagesSkyViper StreamingVideo Spider-Drone Instructions PDFJaskaran Pal SinghNo ratings yet

- 2018 KDS Aerial Targets V1 (Complete)Document21 pages2018 KDS Aerial Targets V1 (Complete)Avdhesh KhaitanNo ratings yet

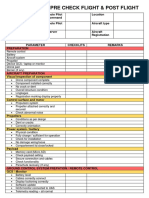

- Multirotor Pre-Flight & Post-Flight ChecklistsDocument2 pagesMultirotor Pre-Flight & Post-Flight ChecklistsArifiani ChannelNo ratings yet

- Rotor Drone 10.11 2021Document68 pagesRotor Drone 10.11 2021Jose A. HerreraNo ratings yet

- Piccolo Nano Data Sheet - 13-S-1150Document2 pagesPiccolo Nano Data Sheet - 13-S-1150Jacinto HernandezNo ratings yet

- Making Life Easier For BVLOS Drone OperatorsDocument1 pageMaking Life Easier For BVLOS Drone OperatorsaNo ratings yet

- PDF - Object Detection and Person Tracking Using UavDocument11 pagesPDF - Object Detection and Person Tracking Using UavVj KumarNo ratings yet

- Ad8705 Ai&r Unit 1Document25 pagesAd8705 Ai&r Unit 1Nandhini BalamuruganNo ratings yet

- Supply Chain and Operations Insights from IIT BombayDocument46 pagesSupply Chain and Operations Insights from IIT BombaySagar ShahNo ratings yet

- Reasons WHY YOU Should: Train WithDocument14 pagesReasons WHY YOU Should: Train WithShivam KapoorNo ratings yet

- Drones DocumentDocument2 pagesDrones DocumentHumuza Innovation HubNo ratings yet

- AV New AVX Series Wind TurbineDocument2 pagesAV New AVX Series Wind Turbinekulov1592No ratings yet

- Project Final PPT 1Document20 pagesProject Final PPT 1AnasNo ratings yet

- List of Eqpt and Spares of ArtilleryDocument4 pagesList of Eqpt and Spares of ArtilleryaceninjaNo ratings yet

- SURVEY OF UAV APPLICATIONS IN CIVIL MARKETS (June 2001)Document11 pagesSURVEY OF UAV APPLICATIONS IN CIVIL MARKETS (June 2001)indrawantanjungNo ratings yet