Professional Documents

Culture Documents

GHFFG PDF

Uploaded by

George Herland PradiktaOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

GHFFG PDF

Uploaded by

George Herland PradiktaCopyright:

Available Formats

British Journal of Anaesthesia 1995; 74: 517-520

Prophylactic i.m. ephedrine in bupivacaine spinal anaesthesia

J.-E. STERNLO, A. RETTRUP AND R. SANDIN

Summary

In a double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized

study, we have investigated the efficacy of i.m.

ephedrine in 98 elderly patients undergoing hip

arthroplasty under spinal anaesthesia with plain

bupivacaine. Fifty patients received ephedrine

0.6 mg kg"

1

body weight, deep in the paravertebral

muscles immediately after injection of bupivacaine,

and 48 received an equal volume of saline. Patients

in both groups were given the same volumes of

fluid before anaesthesia. Systolic arterial pressure

during the first 60 min after anaesthesia remained

significantly more stable in the ephedrine-treated

group, and there was also a significantly smaller

number of patients in this group who had decreases

in pressure of more than 30% of pre-block levels,

and fewer required rescue i.v. ephedrine. An

increase in heart rate or systolic pressure of ^ 20%

from baseline was found in two patients in the

ephedrine group and in one patient in the placebo

group. We conclude that ephedrine 0.6 mg kg"

1

body weight administered in the paravertebral

muscles immediately after plain bupivacaine spinal

anaesthesia is a simple and effective means of

reducing the incidence of hypotensive episodes in

the elderly patient. (Br. J. Anaesth. 1995; 74:

517-520)

Key wor ds

Anaesthetic techniques, subarachnoid. Sympathetic nervous

system, ephedrine. Complications, hypotension.

Ephedrine is an alkaloid originally extracted from

the Chinese plant Ma Huang, used in traditional

Chinese medicine for centuries. In the late 1920s,

this sympathomimetic amine was introduced as a

vasopressor into anaesthetic practice by Ockerblad

and Dillon [1]. Its modern synthetic congener

remains a drug of choice for treating hypotension

induced by spinal or extradural anaesthesia [2]. The

dose and timing of administration, however, have

not been fully investigated, although the trend today

seems to favour i.v. administration, either in titrated

single doses or as a continuous infusion. The efficacy

of prophylactic i.m. ephedrine has been questioned

and there is concern regarding the potential for

causing harmful hypertension or tachycardia [2-5].

However, Hemmingsen, Poulsen and Risbo

administered a combination of i.v. and i.m. eph-

edrine after bupivacaine spinal anaesthesia, and

found this regimen satisfactory in counteracting

hypotension without undue hypertension or tachy-

cardia [6]. In all previous studies with the i.m. route,

fixed doses of ephedrine have been used.

The aim of our study was to investigate the

efficacy of ephedrine in maintaining haemodynamic

stability in elderly patients when administered in a

single i.m. dose determined by body weight and

given at the same time as spinal anaesthesia.

Patients and methods

This double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized

study was approved by the Ethics Committee at the

University in Linkoping. We studied 100 consecu-

tive patients undergoing total hip replacement under

spinal anaesthesia with plain bupivacaine. One

patient was excluded as it was not possible to

perform the spinal block, and another because of

incomplete data, leaving 98 patients for evaluation.

Premedication was given approximately 1 h before

anaesthesia with i.m. ketobemidone 5-10 mg and

i.m. dixyrazine 10-20 mg according to age and body

weight (ketobemidone is not available in the UK;

ketobemidone is an opioid, 5 mg is equipotent to

morphine 5-8 mg [7], dixyrazine is a low-dose

phenothiazine with sedative and marked antiemetic

properties [8]). Patients medicated with beta receptor

or calcium channel blockers were given their or-

dinary morning doses. During the 20-min period

before anaesthesia the patients received 3 % dextran

solution (Plasmodex, Pharmacia AB, Sweden) 7 ml

kg"

1

body weight. Systolic arterial pressure (SAP)

was measured with a calibrated aneroid sphyg-

momanometer and radial pulse palpation. Heart rate

(HR) was obtained from a three-lead ECG. Spinal

anaesthesia with 0.5 % plain bupivacaine 20 mg was

performed in the L2-3 or L3-4 interspaces with the

patient in the sitting position. Morphine 0.3 mg was

added to the bupivacaine solution. Immediately after

completion of the spinal injection, the needle was

withdrawn and redirected laterally, and 0.012 ml

kg"

1

body weight of the trial solution was injected

deep into the paravertebral muscles. The solution

comprised either ephedrine 0.6 mg kg"

1

body

weight or saline. The patient was then placed

immediately in the lateral position. After anaesthesia,

J.-E. STERNLO, MD, DEAA, A. RETTRUP, RN, R. SANDIN, MD, PHD,

Department of Anaesthesia, Lanssjukhuset, S-391 85 Kalmar,

Sweden. Accepted for publication: December 2, 1994.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

6

,

2

0

1

2

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

j

a

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

518 British Journal of Anaesthesia

the 3 % dextran solution was continued at a rate of

1 ml kg"

1

h"

1

and a crystalloid solution with 2.5 %

glucose (Rehydrex Pharmacia AB, Sweden) was

started and continued at a rate of 4 ml kg"

1

h"

1

throughout surgery.

A decrease in SAP of > 30 % from the baseline

recording to less than 100 mm Hg was treated

immediately with i.v. ephedrine in 5-mg increments

until a stable SAP above this threshold level was

established. Plasma volume maintenance with 3%

dextran (in addition to the continuous infusion rate

of 1 ml kg"

1

h"

1

) and packed red cell transfusions to

compensate for intraoperative blood loss were based

on a computer-generated scheme for each individual

patient, taking into account age, sex, body weight

and height, preoperative haemoglobin (Hb) con-

centration and predetermined lowest acceptable

postoperative Hb. In order to provide a comfortable

state during surgery, midazolam was administered as

required in doses of 1.25 mg. In a few patients small

doses of i.v. fentanyl were given to alleviate pain

from unanaesthetized areas caused by the uncomfort-

able lateral position. Dixyrazine was given in i.v.

doses of 5 mg to treat nausea.

SAP and HR were recorded before anaesthesia, 2

and 5 min after anaesthesia, and every 5 min there-

after. All SAP measurements were obtained from the

upper arm. A reduction in SAP > 30 % from the

baseline level was considered a negative outcome in

terms of efficacy, whereas increases in SAP ^ 20 %

to a level ^160 mm Hg, and in HR ^ 20 % to a level

^ 90 beat min"

1

were considered adverse reactions.

The groups were compared by Mann-Whitney U

test and regression analysis, as appropriate. P < 0.05

was considered significant.

Results

There were no differences between the groups in

patient characteristics, baseline haemodynamic state,

time from anaesthesia to surgery, intraoperative

volume replacement or bleeding (table 1). There

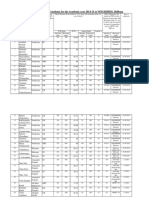

Table 1 Patient data, peroperative blood loss, and fluid and

blood replacement (mean (SD or range) or number). No

significant differences between groups

Table 2 Cumulated doses of midazolam and fentanyl (mean

(SD) [range]). Median = 0 for fentanyl in both groups, and

1.25 mg for midazolam in both groups. No significant

differences between groups

Sex (M: F)

Age (yr)

ASA I: II: III:IV

p and/or Ca blockers ()

Height (cm)

Weight (kg)

Haemoglobin (g dl"

1

)

SAP (mm Hg) (upper arm,

lateral pos.)

HR (beat min-

1

)

Duration of surgery (min)

Time anaesthesia to surgery

(min)

Peroperative blood loss (litre)

3 % Dextran (litre)

Crystalloid (litre)

Packed red cells (litre)

Placebo

group

48

20:28

69 (43-86)

18:24:6:0

12

168 (8)

73(15)

13.7(1.5)

143(26)

74(12)

118(34)

48(11)

1.1(0.7)

1.2 (0.3)

1.3 (0.4)

0.26 (0.47)

Ephedrine

group

50

20:30

70 (37-89)

21:20:8:1

7

168 (9)

76 (16)

13.7(1.8)

148(31)

75(12)

114(33)

51 (10)

1.0(0.6)

1.1(0.3)

1.2(0.4)

0.32 (0.49)

Midazolam (mg)

Fentanyl (|ig)

160 T

150

- 1 4 0 -

I

130-

E

o. 120-

w

no

100-

90-

<

1

) T

Ephedrine group

1.3 (1.3) [0-5]

6.0 (22.0) [0-100]

Placebo group

1.2 (1.2) [0-3.75]

1.0 (8.0) [0-50]

10 20 30 40

Time (min)

50 60

Figure 1 Systolic arterial pressure (mean, SEM) during the first

60 min after anaesthesia in the placebo (O) and ephedrine ( #)

groups. Except at time = 0, all differences were significant

(P < 0.05).

were no significant differences in the amount of

midazolam or fentanyl given within 5, 10, 30 and

60 min after anaesthesia or in the total cumulated

doses throughout the whole procedure (table 2).

Spinal anaesthesia was successful in all patients.

The median values of the upper segmental sensory

level of the spinal anaesthesia (determined by the

cold discrimination test) were T4 (range T3-10) and

T5 (T2-10) for the ephedrine-treated and placebo

groups, respectively. Regression analysis did not

reveal any significant relation between the level of

sensory analgesia and SAP every 5 min during the

first 60 min after the block. The incidence of nausea

and vomiting and the amounts of antiemetics

administered during operation and within 12 h after

operation did not differ significantly between the

groups. SAP in the placebo group was significantly

lower compared with the ephedrine group when

assessed every 5 min after anaesthesia, and the

reduction in SAP compared with the corresponding

baseline value was significantly more pronounced in

the placebo group 10 min after anaesthesia (P <

0.008) and throughout the first hour after anaesthesia

(fig. 1). There were also statistically significant

differences between the groups in the percentage of

patients given rescue i.v. ephedrine aimed at main-

taining SAP above the threshold level (fig. 2). These

differences were apparent when the groups were

compared during the first 60 min after anaesthesia,

and also throughout the whole procedure.

The number of patients with reductions in SAP of

more than 30% from the baseline level was signifi-

cantly lower in the ephedrine group at 10, 25, 45, 50

and 55 min after anaesthesia (table 3). No patient in

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

6

,

2

0

1

2

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

j

a

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

Prophylactic ephedrine 519

80

60

s .

4 0

-^ 20

< 30 min 30-60 min > 60 min i Total

Figure 2 Percentage of patients given i.v. rescue ephedrine

according to study criteria with regard to time after anaesthesia

in the ephedrine ( ) and placebo ( ) groups. The difference

obtained within 30 min was significant at P < 0.01 and the

other comparisons at P < 0.001.

Table 3 Number of patients with a reduction in systolic

arterial pressure > 30 % of that before anaesthesia within the

first hour after anaesthesia (mean reduction (Reduction %)).

Group P = placebo, group E = ephedrine. * P < 0.05

Time after block

(min) Group n

Reduction

o/

/o

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

55

60

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

P

E

3

0

10*

0

6

2

6

2

6*

1

7

3

12

9

16

9

16*

6

20*

7

24*

7

20

11

44

34

38

33

36

37

37

33

34

37

39

33

39

36

35

39

38

36

37

39

38

36

the placebo group received midazolam or fentanyl

within 10 min after anaesthesia and after sedatives or

analgesics were administered, no correlations be-

tween SAP and administration of these drugs were

found.

Seven patients in the ephedrine group and 12 in

the placebo group were receiving medication with

beta adrenergic, calcium channel blockers, or both.

In these patients the value of SAP was higher at all

times after anaesthesia if prophylactic ephedrine had

been given and this difference was statistically

significant at 10 min, and between 35 and 60 min of

anaesthesia. The need for rescue i.v. ephedrine in

patients treated with beta adrenergic, calcium chan-

nel blockers, or both, was significantly less if

prophylactic ephedrine had been given (table 4). In

the corresponding subgroup of patients not treated

with beta adrenergic or calcium channel blockers,

the significant differences in SAP between the two

groups were consistent with the data for all of the

patients studied, as indicated in figure 1. The need

for rescue ephedrine in patients not treated with beta

adrenergic or calcium channel blockers is shown in

table 4.

An increase of more than 20% in SAP (from 160

to 210mmHg) was observed in one patient in the

ephedrine-treated group. HR was unchanged at 120

beat min"

1

. One patient in each group had an increase

in HR of more than 20%, the one in the untreated

group from 95 to 125 beat min"

1

and in the ephedrine

group from 80 to 107 beat min"

1

.

Discussion

Hypotension after spinal or extradural block may be

hazardous in patients with a compromised arterial

supply to vital organs (i.e. coronary and cerebral

circulations), but may also reflect a reduction in

afterload, which in most cases is beneficial [3]. As

there is no method to assess with accuracy the lowest

acceptable arterial pressure in the individual patient,

the decision to administer drugs to increase arterial

pressure is dependent on the anaesthetist's judge-

ment. Thus our decision to give i.v. ephedrine if

SAP decreased by more than 30% to less than

100 mm Hg was partly empirical.

It has been observed that volume expansion alone

with colloid or crystalloid solutions has not been

consistently effective in attenuating hypotension

induced by spinal or extradural anaesthesia and it

may even by harmful in the elderly patient with

incipient heart failure [2, 3]. Of the vasoactive drugs

suitable for prophylaxis, ephedrine is generally

agreed as the most appropriate. I.v. infusions of

ephedrine or intermittent i.v. doses titrated to

response are the techniques most often recom-

mended. However, as hypotension may develop

rapidly after spinal anaesthesia, optimal SAP control

with these techniques calls for very close monitoring

by invasive or automated techniques, and these are

not always feasible. On the other hand, i.m. prophy-

lactic administration of ephedrine is generally not

recommended because of the alleged unpredictable

absorption from the injection site and the belief that

a relative overdose may result in hypertension,

Table 4 Number of administered rescue doses of ephedrine (5 mg i.v.) within 1 h after anaesthesia (< 1 h) and

during the entire procedure (Total) in patients with (cardiovascular medication) and without (no cardiovascular

medication) treatment with beta-adrenergic, calcium channel blockers, or both. Data are mean (SD) [median]

Cardiovascular medication No cardiovascular medication All patients

Placebo

(n = 12)

Ephedrine

( = 7) P

Placebo

(n = 36)

Ephedrine

(n = 43) P

Placebo

( = 48)

Ephedrine

(n = 50) P

< l h 1.8 (1.2) [2] 0.3 (0.5) [0] 0.01

Total 3.8 (2.0) [4] 1.0 (1.9) [0] 0.01

0.8 (1.2) [0] 0.2 (0.5) [0] 0.01

2.1 (1.8) [2] 0.9 (1.5) [0] 0.01

1.0 (1.3) [1] 0.2 (0.5) [0] 0.0001

2.5 (2.0) [2] 1.0 (1.5) [0] 0.0001

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

6

,

2

0

1

2

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

j

a

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

520 British Journal of Anaesthesia

tachycardia, or both, which may be detrimental [2,

3]. Indeed, use of the i.m. route in obstetric spinal or

extradural anaesthesia has been condemned. In a

study by Rolbin and colleagues in which ephedrine

was given i.m. 15-30 min before extradural an-

aesthesia for elective Caesarean section, ephedrine

25 mg was ineffective in reducing the incidence

of maternal hypotension, while a dose of 50 mg

produced unacceptable hypertension which was

associated with derangement in fetal acid-base status

[4]. Rout and co-workers also recommended that

prophylactic i.m. ephedrine not be used before

obstetric spinal or extradural anaesthesia in case the

block should fail and it became necessary to resort to

general anaesthesia [5].

However, in non-obstetric cases, Hemmingsen,

Poulsen and Risbo administered i.m. ephedrine

37.5 mg after an initial i.v. bolus of 12.5 mg. This

was compared with placebo in 48 patients under-

going surgery of the lower abdomen or lower

extremities during bupivacaine spinal anaesthesia.

Greater stability of arterial pressure occurred in

ephedrine-treated patients, especially in a subgroup

of ASA III patients, where all eight patients in the

placebo group had a decrease in mean arterial

pressure exceeding 33 % compared with none in the

ephedrine-treated group. Tachycardia or hyperten-

sion was not observed [6].

It seems that the problem associated with i.m.

ephedrine is that of a reliable regimen which is both

effective and also avoids overdosage. Surprisingly,

matching the dose to body mass has not been

undertaken in the earlier studies. From our previous

clinical experience it seemed that an i.m. dose of

0.6 mg kg"

1

was appropriate and that reliable ab-

sorption could be expected if ephedrine was injected

deep into the paravertebral muscles. In our study we

found that this regimen provided a significant

stabilizing effect on SAP throughout the study

period of 1 h and that this effect was evident both in

the presence and absence of beta adrenergic or

calcium channel blockers, or both.

The detailed part of this study was terminated

60 min after anaesthesia, as we expected that the

effects of i.m. ephedrine would have terminated

within this period and also we expected that any

difference in haemodynamic state would be in-

fluenced or obscured by surgical blood loss and

cementing. Nevertheless, the percentage of patients

treated with i.v. ephedrine after the first 60 min was

also significantly higher (70 % vs 31 %; P < 0.001) in

the placebo group.

The price paid for SAP stability in the ephedrine

group may have been a 31 % increase in SAP in a

patient suffering from heart failure, atrial fibrillation

and diabetes who was haemodynamically unstable

both before and during anaesthesia. Increases in HR

occurred in one patient in each group. These results

must be weighed against the significantly inferior

haemodynamic stability in a substantial number of

patients in the placebo group. The incidence of

nausea and vomiting during and after operation was

not affected by the use of ephedrine [9] and there was

no effect on blood loss and need for intraoperative

transfusion [10]. Finally, it should be emphasized

that we used plain bupivacaine, which has a rather

slow onset of action compared with other local

anaesthetics [11]. Our results can not be indis-

criminately applied therefore to all situations where

spinal anaesthesia is used.

References

1. Ockerblad NF, Dillon TG. The use of ephedrine in spinal

anesthesia. Journal of the American Medical Association 1927;

88: 1135-1136.

2. Morgan P. The role of vasopressors in the management of

hypotension induced by spinal and epidural anaesthesia.

Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia 1994; 41: 404-413.

3. McCrae AF, Wildsmith JAW. Prevention and treatment of

hypotension during central neural block. British Journal of

Anaesthesia 1993; 70: 672-680.

4. Rolbin SH, Cole AFD, Hew EM, Pollard A, Virgint S.

Prophylactic intramuscular ephedrine before epidural an-

aesthesia for caesarean section: Efficacy and actions on the

foetus and newborn. Canadian Anaesthetists Society Journal

1982; 29: 148-153.

5. Rout CC, Rocke DA, Brijball R, Kovarjee RV. Prophylactic

intramuscular ephedrine prior to caesarean section. An-

aesthesia and Intensive Care 1992; 20: 448-452.

6. Hemmingsen C, Poulsen JA, Risbo A. Prophylactic ephedrine

during spinal anaesthesia: double-blind study in patients in

ASA groups IIII. British Journal of Anaesthesia 1989; 63:

340-342.

7. Ohqvist G, Hallin R, Gelinder S. A comparison between

morphine, meperidine and ketobemidone in continuous

intravenous infusion for postoperative pain relief. Acta

Anaeslhesiologica Scandinavica 1991; 35: 4448.

8. Larsson S, Hagerdal M, Lundberg D. Premedication with

intramuscular dixyrazine. A controlled double-blind com-

parison with morphine-scopolamine and placebo. Ada

Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 1988; 32: 131-134.

9. Rothenberg DM, Parnass SM, Litwack K, McCarthy RJ,

Newman ML. Efficacy of ephedrine in the prevention of

postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesthesia and Analgesia

1991; 72: 58-61.

10. Thorburn J. Subarachnoid blockade and total hip replace-

ment. Effect of ephedrine on intraoperative blood loss. British

Journal of Anaesthesia 1985; 57: 290-293.

11. Tuominen M. Bupivacaine spinal anaesthesia. Acta Anaes-

thesiologica Scandinavica 1991; 35: 110.

b

y

g

u

e

s

t

o

n

A

u

g

u

s

t

6

,

2

0

1

2

h

t

t

p

:

/

/

b

j

a

.

o

x

f

o

r

d

j

o

u

r

n

a

l

s

.

o

r

g

/

D

o

w

n

l

o

a

d

e

d

f

r

o

m

You might also like

- KomDocument8 pagesKomGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- KomDocument8 pagesKomGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- YrtyrtDocument1 pageYrtyrtGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- WWWDocument1 pageWWWGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- Opioid Pharmacology: Pain Physician 2008: Opioid Special Issue: 11: S133-S153 - ISSN 1533-3159Document22 pagesOpioid Pharmacology: Pain Physician 2008: Opioid Special Issue: 11: S133-S153 - ISSN 1533-3159Suresh KumarNo ratings yet

- EeeDocument1 pageEeeGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- RRRHJKKHDocument1 pageRRRHJKKHGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- ZXCDocument1 pageZXCGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- Jbsi 18 NXJPW 0 U 1Document1 pageJbsi 18 NXJPW 0 U 1George Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- BBBDocument1 pageBBBGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- JNC 7 (Klasifikasi Hipertensi) PDFDocument2 pagesJNC 7 (Klasifikasi Hipertensi) PDFAbdur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Googles BookDocument1 pageGoogles BookGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- Popo PopDocument1 pagePopo PopGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- Serial NoDocument1 pageSerial NoGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- Read Me 1Document10 pagesRead Me 1pmk888No ratings yet

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- EulaDocument63 pagesEulatechkasambaNo ratings yet

- List FileDocument73 pagesList FileGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- Accidental Radioactive ContaminationDocument1 pageAccidental Radioactive ContaminationGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- List FileDocument73 pagesList FileGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal VertebraDocument10 pagesJurnal VertebraGeorge Herland PradiktaNo ratings yet

- Higher Algebra - Hall & KnightDocument593 pagesHigher Algebra - Hall & KnightRam Gollamudi100% (2)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5783)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (72)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Syllabus ECDO 4225 - Professional Aspects of Nutrition and DieteticsDocument6 pagesSyllabus ECDO 4225 - Professional Aspects of Nutrition and DieteticsOEAENo ratings yet

- Acute Tracheobronchitis Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentDocument2 pagesAcute Tracheobronchitis Causes, Symptoms, TreatmentNicole Shannon CariñoNo ratings yet

- JUSTINE Medical-for-Athletes-2-1Document2 pagesJUSTINE Medical-for-Athletes-2-1joselito papa100% (1)

- As 2550.5-2002 Cranes Hoists and Winches - Safe Use Mobile CranesDocument8 pagesAs 2550.5-2002 Cranes Hoists and Winches - Safe Use Mobile CranesSAI Global - APACNo ratings yet

- Admission For 1st Year MBBS Students For The Academic Year 2014-2015Document10 pagesAdmission For 1st Year MBBS Students For The Academic Year 2014-2015Guma KipaNo ratings yet

- Appendix - 6 - Site Logistics PlanDocument16 pagesAppendix - 6 - Site Logistics PlanRamesh BabuNo ratings yet

- Anarchy RPG 0.2 Cover 1 PDFDocument14 pagesAnarchy RPG 0.2 Cover 1 PDFanon_865633295No ratings yet

- Weeblylp MedicinaDocument18 pagesWeeblylp Medicinaapi-538325537No ratings yet

- The Process of Grief PDFDocument6 pagesThe Process of Grief PDFnicoletagr2744100% (1)

- Handbook of Laboratory Animal Science - Vol IIIDocument319 pagesHandbook of Laboratory Animal Science - Vol IIICarlos AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Chapter 22 The First Heart SoundDocument5 pagesChapter 22 The First Heart SoundAbhilash ReddyNo ratings yet

- Facts of MaintenanceDocument9 pagesFacts of Maintenancegeorge youssefNo ratings yet

- OCPD: Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument4 pagesOCPD: Symptoms, Diagnosis and TreatmentRana Muhammad Ahmad Khan ManjNo ratings yet

- Introduction 1 Esoteric HealingDocument20 pagesIntroduction 1 Esoteric HealingChicowski Caires100% (1)

- Swan-Ganz Catheter Insertion GuideDocument3 pagesSwan-Ganz Catheter Insertion GuideJoshNo ratings yet

- LabTec Product SpecificationsDocument292 pagesLabTec Product SpecificationsDiego TobrNo ratings yet

- Nursing Interventions for Ineffective Airway ClearanceDocument3 pagesNursing Interventions for Ineffective Airway Clearanceaurezea100% (3)

- EN Sample Paper 12 UnsolvedDocument9 pagesEN Sample Paper 12 Unsolvedguptasubhanjali21No ratings yet

- Injeksi Mecobalamin Vas ScoreDocument5 pagesInjeksi Mecobalamin Vas ScoreHerdy ArshavinNo ratings yet

- College Women's Experiences With Physically Forced, Alcohol - or Other Drug-Enabled, and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Before and Since Entering CollegeDocument12 pagesCollege Women's Experiences With Physically Forced, Alcohol - or Other Drug-Enabled, and Drug-Facilitated Sexual Assault Before and Since Entering CollegeGlennKesslerWP100% (1)

- (260821) PPT Analsis Evaluasi Penggunaan Obat Di FKTPDocument43 pages(260821) PPT Analsis Evaluasi Penggunaan Obat Di FKTPreginaNo ratings yet

- Detailed Advertisement of Various GR B & C 2023 - 0 PDFDocument47 pagesDetailed Advertisement of Various GR B & C 2023 - 0 PDFMukul KostaNo ratings yet

- Occlusion For Implant Suppported CDDocument4 pagesOcclusion For Implant Suppported CDpopat78No ratings yet

- Cough and ColdsDocument3 pagesCough and ColdsKarl-Ren Lacanilao100% (1)

- Labcorp: Patient ReportDocument4 pagesLabcorp: Patient ReportAsad PrinceNo ratings yet

- Leaving Disasters Behind: A Guide To Disaster Risk Reduction in EthiopiaDocument12 pagesLeaving Disasters Behind: A Guide To Disaster Risk Reduction in EthiopiaOxfamNo ratings yet

- Dr. Abazar Habibinia's Guide to Overweight, Obesity, and Weight ManagementDocument41 pagesDr. Abazar Habibinia's Guide to Overweight, Obesity, and Weight ManagementTasniiem KhmbataNo ratings yet

- 798 3072 1 PBDocument12 pages798 3072 1 PBMariana RitaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Hazards For The Nurse As A Worker - Nursing Health, & Environment - NCBI Bookshelf PDFDocument6 pagesEnvironmental Hazards For The Nurse As A Worker - Nursing Health, & Environment - NCBI Bookshelf PDFAgung Wicaksana100% (1)

- Updates On Upper Eyelid Blepharoplasty.4Document8 pagesUpdates On Upper Eyelid Blepharoplasty.4Dimitris RodriguezNo ratings yet