Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Rearch Methods Handbook 866512008

Uploaded by

bdsisira0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

42 views32 pagesMini Hydro

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentMini Hydro

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

42 views32 pagesRearch Methods Handbook 866512008

Uploaded by

bdsisiraMini Hydro

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 32

1

Faculty of Business & Law

School of Strategy and Economics

POSTGRADUATE RESEARCH METHODS

2011/2012

Masters Level

Student Name:

Module Tutor

E-mail address

Telephone number

2

Leeds Metropolitan University

Faculty of Business & Law

Module Title: Postgraduate Research Methods

Pre-Requisites: None

CRN: Various

Academic Year: 2011/2012 Level: Masters Block or Workshop Delivery

Module Leader: Dr Tim Bickerstaffe

Module Team: Dr Tim Bickerstaffe; Junjie Wu,

Lawrence Bailey; Mary Leung

The module:

The modules link to your dissertation

A postgraduate Masters level dissertation requires students to develop and demonstrate powers of

rigorous analysis, critical inquiry, clear expression, and independent judgement in relation to an area

of business and management activity.

Many postgraduate dissertations are based upon an in-depth investigation into a managerial problem

either within the students own organization or a client organization where the student is not a direct

employee.

However, as the requirement is to undertake an academic dissertation at Masters level successful

dissertations address more than just problem solving typical of much mainstream management

consultancy.

The most successful Masters dissertations show that the student has stood back from the problem,

conceptualized it, and explored its wider implications for other managers outside the particular case.

To help students achieve this, and reflecting the requirements of Masters study there is also an

emphasis upon students demonstrating methodological competence so that they:

can systematically justify their choice of approach to collecting data;

can competently undertake any data collection;

are able to analyze that collected data and make sense of its implications for the

dissertations aims, objectives and research questions;

can demonstrate an understanding of the strengths and weaknesses of the approach used

with reference to findings;

can demonstrate an appreciation of the applicability of any findings, often with particular

reference to managerial implications either within the organizations studied or more generally

and often both.

It is these specific competences that the research methods module is designed to help you develop

over the two semesters that the module runs.

3

Module Learning Outcomes

To understand, critically analyze, evaluate and explain:

Different business and management research designs and the assumptions on which they are

based;

The nature of research problems, the stages of a research process and the criteria for

selection of research methods;

Ethical considerations and issues associated with the selection of a research problem and the

research process.

To be able to:

Identify clear research questions (or hypotheses) and assess what is an appropriate and

manageable research design for a particular question;

Identify and assess appropriate methodological approaches, methods of investigation and of

data analysis for particular research questions;

Develop a structured programme of research as a formal proposal in pursuit of a Masters

Dissertation based upon informed choices about the research designs, techniques and

procedures to be followed;

Conduct research in a systematic, rigorous and critically reflective manner;

Synthesise data from a wide variety of sources with due regard to issues of generalisability,

validity and reliability within an acceptable dissertation format.

Key Skills:

Location and utilization of contextualized information sources;

Critical review and reflexive commentary of contemporary information;

Requirement specification and project rationale/justification;

Sensitivity to impact upon affected/vulnerable groups;

Negotiation of access to resources;

Project management and project planning;

Selection and justification of a relevant research design and supporting methodology;

Manipulation, interpretation and analysis of data in support of specified rationale(s);

Relative assessment and measurement of value;

Appropriately contextualized, justified and structured presentation of results.

4

Teaching & Learning Techniques:

To help you develop the knowledge and skills required to pass this module, the module team will use a

blend of teaching and learning techniques to help you.

Lectures:

The standard delivery pattern of the module requires students to attend and actively participate in six

(6) one hour lectures (3 per semester) and 12 one hour tutorials (6 per semester).

Tutorials:

Each tutorial is closely associated to the lecture series and follows student progression through a

series of tutor-facilitated tasks. Alternatives to this standard delivery pattern will facilitate

contextualization to alternative course/programme requirements. Tutorial groups will be assigned and

contextualized on a course basis.

Xstream Site:

Xstream provides a central focus and one additional route to wider teaching and learning resources for

the module. Among other things, resources on Xstream include: the e-Module Handbook, copies of

Lecture Slides; Guidance on Assessment; dedicated Journal Articles; several Guides to certain

Research Techniques; and a wider range of additional facilities.

Self-Directed Study:

The teaching and learning strategies are based on the assumption that all participating students will

employ independent and interdependent learning skills, which will have been developed prior to

attending the module and at an earlier stage of their learning programme.

Your Responsibilities:

At Masters level all students must take a high degree of responsibility for their own self-directed

learning. Whilst numerous support facilities exist, it is the sole responsibility of each student to ensure

sufficient student is undertaken.

How to Succeed in this Module:

1. Attend all 6 lectures

Make notes during lectures;

Proactively review your notes and discuss with tutors/fellow students afterwards;

Proactively review recommended reading prior to and after attending Lectures (see Lecture

Slides on Xstream);

Supplement recommended reading with further self-directed study.

2. Attend and Actively Participate in all 12 Seminars

Undertake any/all preparatory work prior to attending each Seminar in accordance with

instructions given by your tutor;

Make notes and take part in all Seminar activities;

Ask questions during seminars to clarify queries and guide additional self-directed study;

Proactively review your notes and discuss each Seminar with fellow students afterwards.

3. Supplement Timetables Classes with a Clear Plan of Self-Directed Study

Use materials/links on Xstream to support a clearly structured plan of self-directed study for

this module;

Link progression of your studies for Research Methods to progression with your Dissertation;

Contact the Research Methods Module Leader to clarify outstanding queries (during lectures

or via email);

5

Assessment

Method:

Weighting:

Assessment

Date/Hand In;

Feedback

Method:

Feedback Date:

Dissertation

Topic

0% TBC N/A N/A

Assessment

Method:

3000-word

Dissertation

Proposal

100% TBC Via Email TBC

Extend self-directed study for Research Methods into self-directed study for your Dissertation.

4. Ask for Extra Tailored Support and Guidance via Feedback Opportunities Available

Significant investments have been made to provide you with a wide range of resources to

support your learning in this module;

Members of the Module Team are keen to structure their teaching plans in accordance with

your specific needs;

In order to do this we require your feedback which should be offered in an appropriate and

responsible manner at the earliest opportunity and to the member of the Module Team directly

concerned (your tutor or the Module Leader).

5. Proactively Prepare for Module Assessment

Assessment Performance Levels are closely linked to Levels of Achievement in paragraphs 1

-3 (above);

You alone are responsible for managing your performance and the level of assessed

achievement in this module;

Start early, stick to clearly formulated plans, be proactive in your learning, and use the wide

range of learning opportunities and resources available.

6

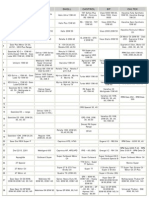

The Teaching and Learning Programme

DATE (w/c)

LECTURE

TUTORIAL

Tutorial Reading/

Preparation

30 September/

3 October

Research and Your

Dissertation

Research and Your

Dissertation

p.9

10 October/

17 October

Dissertation Topic

Selection

Dissertation Topic

Selection

p.10

24 October/

31 October

Research Strategy

& Design

Introduction to

Dissertation Proposals

p.11

7 November/

14 November

Proposal Strategies &

Design

p.12

21 November/

28 November

Research Ethics

pp.13-14

5 December/

12 December

Critical Reading &

Literature Reviews

p.15

30 January/

6 February

Secondary Data

Collection & Analysis

Literature Reviews for

Proposals

p.16

13 February/

20 February

Principles of

Quantitative Research

Surveys &

Questionnaire Design

pp.17-18

27 February/

5 March

Principles of

Qualitative Research

Analysing & Interpreting

Quantitative Data

p.19

12 March/

19 March

Interviews &

Discussion Guide Design

p.20

26 March/

16 April

Analysing & Interpreting

Qualitative Data

p.21

23 April/

30 April

Review of the

Dissertation Process

p.22

7

The Lectures

LECTURE 1

Research and Your Dissertation

This lecture will introduce you to the module, reveal the importance of research to contemporary business

and management as well as to your dissertation and provide an overview of the modules structure and

delivery.

The Research Methods and Dissertation modules provide you with the opportunity to explore an area of

interest within strategic management in greater depth. Transferable skills in research, information and

project management will be developed, equipping you for the continuously changing business environment

of the 21

st

century. The aim of the module is to enable you to undertake a self-managed process of

systematic academic enquiry within the domain of business and management.

LECTURE 2

Critical Thinking and Turning Ideas into Research Objectives

In everyday English language, being critical means finding fault and being negative about something. It

can often be quite destructive rather than constructive, and is often done with a particular antagonistic

motive or attitude. Critical Thinking, in the academic sense, is the ability to evaluate the validity and

strength of arguments and propositions. Developing a critical stance in this context means not being purely

destructive; rather it entails a rigorous and structured approach, and should generate insights that are

valuable in taking practical action.

Formulating and clarifying the research topic is the starting point of your dissertation. Once you are clear

about this, you will be able to choose the most appropriate research strategy and data collection and

analysis techniques. Masters level dissertations are distinguished from other forms of business and

management research by their attempt to analyse situations in terms of the bigger picture; they seek

answers, explanations, make comparisons and arrive at generalisations which can be used to extend

theory as well as what, they address why? The most successful dissertations are those which are

specific and focused. The more clearly a dissertation topic is defined the more efficient and effective the

execution of the project will be.

LECTURE 3

Research Strategies and Design

Research objectives are the specific components of the research topic or problem and they set out what

your research will examine and what issues the dissertation will cover. The next step involves deciding on

the correct research design for the project. A research design provides a framework for the collection and

analysis of data. A choice of research design effects decisions about the priority being given to a range of

dimensions of the research process.

It can be useful to consider the dissertation proposal as your projects research strategy and design. The

content of the dissertation proposal should inform the reader about what you want to research, why you

want to research it, what you are trying to achieve, and how you plan to achieve it.

8

LECTURE 4

Secondary Data Collection and Analysis

The focus of this lecture is data gathering through secondary sources. In considering secondary sources,

the focus will be on conducting a literature review and the strategies for gathering existing material

generated by other researchers and authors. The lecture will also highlight the importance of correct

referencing and the avoidance of plagiarism.

LECTURE 5

Principles of Quantitative Research

Quantitative research methods are primarily concerned with gathering and working with data that is

structured and can be represented numerically. Quantitative data is typically gathered when a positivist

approach is taken and data is collected that can be statistically analysed

LECTURE 6

Principles of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research methods are primarily concerned with stories and accounts, including subjective

understandings, opinions, feelings and beliefs. Qualitative data is typically gathered when an interpretivist

approach is taken and when the data is collected is the words or expressions of the research participants

themselves.

9

The Tutorials

1. Research and Your Dissertation

Business and management research not only needs to provide findings that advance knowledge and

understanding, it also needs to address business issues and practical managerial problems. This tutorial

will introduce you to the continuum on which all business and management research projects can be

placed.

On the one hand, there is the research that is undertaken purely to understand the processes of business

and management and their outcomes. This is often termed basic, fundamental or pure research. On the

other hand, there is the research that is argued to be of direct and immediate relevance to managers,

addressing issues that they see as important, and presented in ways that they understand and can act on.

This is termed applied research.

The tutorial will also begin the process of helping you generate ideas for your dissertation by preparing you

for a class exercise to be undertaken in Tutorial 2.

Key Readings:

The two texts below have multiple copies held by the library and are very good introductions to both

business research methods and the process of undertaking a dissertation. All tutorial topics carry

recommended reading from both texts.

Saunders, M., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2009) Research Methods for Business Students: 5

th

Edition

Harlow: Pearson pp.2-18

Bryman, A & Bell, E (2007) Business Research Methods: 2

nd

Edition Oxford: University Press pp.4-

36

10

2. Dissertation Topic Selection

The topic you choose to research has a great influence on how well you will succeed in carrying out the

investigation and in writing up your work. A crucial factor is whether you have a genuine interest in the

subject matter, as this will motivate you to complete the task to the best possible standard. In addition,

many practical matters need to be taken into account, such as the availability of relevant resources, or the

feasibility of the intended investigation.

In introducing you to a useful approach to refining research ideas, the tutorial will use the Delphi

Technique. This involves using a group of people who are either involved or interested in the research

idea to generate and choose a more specific research idea. To use this technique you need:

1. to brief the members of the group about the research idea;

2. at the end of the briefing to encourage group members to seek clarification and more information as

appropriate;

3. to ask each member of the group, including the originator of the research idea, to generate

independently up to three specific research ideas based on the idea that has been described;

4. to collect the research ideas in an unedited and non-attributable form and to distribute them to all

members of the group;

5. a second cycle of the process (steps 2 to 4) in which individuals comment on the research ideas

and revise their own contributions in the light of what others have said;

6. subsequent cycles of the process until a consensus is reached. These either follow a similar pattern

(steps 2 to 4) or use discussion, voting or some other method.

Intended Learning Outcomes:

Following this tutorial (and the accompanying lecture), you should be able to:

generate ideas that will help in the choice of a suitable research topic;

identify the attributes of a good research topic;

undertake a Delphi consultation

Key Readings:

Bryman & Bell (2007:75-89)

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill (2009:20-41)

Supplementary Readings:

Romano, A.R. (2010) Malleable Delphi: Delphi Research Technique, its Evolution and Business

Applications in International Review of Business Research Papers 6:5 pp.235-243

Amos, T & Pearse, N (2008) Pragmatic Research Design: an Illustration of the Use of the Delphi

Technique in The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6:2 pp.95-102

Grisham, T (2008) The Delphi Technique: a Method for Testing Complex and Multifaceted Topics in

International Journal of Managing Projects in Business 2:1 pp.112-130

Facione, P (2011) Critical Thinking: What It Is and Why It Counts available at:

http://www.insightassessment.com accessed August 1 2011

11

3. Introduction to Dissertation Proposals

The discipline of composing a research proposal is a very valuable as well as a necessary exercise. The

benefits include:

ensuring your research has aims and objectives that are achievable in the time allocated;

compelling you to read and review some of the relevant background literature and material to

orientate your thoughts;

checking that you have a realistic notion of the research methods you could and should use;

making sure you think about resources you may require at an early stage;

verifying that you have considered ethical issues relating to your research;

assisting you to create an outline structure for your dissertation, and;

helping you to create a viable timetable for your work.

Intended Learning Outcome:

Following this tutorial (and the accompanying lecture), you should be able to:

turn research ideas into a research project that has clear research question(s) and objectives;

Key Readings:

Bryman & Bell pp.74-92

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill pp.32-56

Supplementary Reading:

Baker, M.J. (2000) Writing a Research Proposal in The Marketing Review Vol. 1 pp.61-75

12

4. Proposal Strategy and Design

Focusing on the different kinds of research design requires you to pay attention to the different frameworks

for the collection and analysis of data. A research strategy and design relates to the criteria that are

employed when evaluating both academic dissertations and business research projects in general. It is a

framework for the generation of evidence that is suited both to a certain set of criteria and to the research

objective in which you are interested.

This tutorial will highlight the crucial role of theory in helping you decide your approach to research design.

However, your consideration of theory should begin earlier than this. It should inform your definition of

research questions and objectives before you begin framing your proposal strategy and design.

Definition:

Theory 1. (in natural and social science) any set of hypotheses or propositions, linked by logical or

mathematical arguments, which is advanced to explain an area of empirical reality or type of phenomenon.

2. in a looser sense, a set of ideas or related concepts which can be used to explain and understand an

event, situation, or social phenomena

Concept 1. categories for the organisation of ideas and observations. The building blocks of theory.

2. in a looser sense, the idea or meaning conveyed by a term.

Intended Learning Outcomes:

Following this tutorial (and the accompanying lecture), you should be able to:

identify and begin your understanding of the ideas and approaches to viewing and gathering

knowledge, which provide the basic ways of addressing a topic

Key Readings:

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill pp.136-167; 106-135

Bryman & Bell pp.38-73; 3-37

Supplementary Readings:

Whetton, D.A. (1989) What Constitutes a Theoretical Contribution? in Academy of Management Review

14:4 pp.490-495

Sutton, R.I. & Staw, B.M. (1995) What Theory is Not in Administrative Science Quarterly Vol. 40 pp.371-

384

13

5. Research Ethics

In the context of research, ethics refers to the appropriateness of your behaviour in relation to the rights of

those who become the subject of your work, or are affected by it. The Academy of Management Code of

Ethics (2005) provides a set of general principles to act as a guide for members in determining ethical

course of action in various contexts. These principles refer to professional and scientific responsibility;

integrity, and; respect for peoples rights and dignity.

Research ethics relates specifically to questions about how you formulate and clarify a research topic, how

you design the research and gain access to research subjects and/or participants, how you collect data,

how you process and store data, and how you analyse data and write up your research findings in a moral

and responsible way.

The Tutorial Exercise is intended for you to examine research ethics more specifically in two specific

contexts. These two contexts are presented as short case studies.

[Case studies in social research entail the detailed and intensive analysis of a single phenomenon either

for its own sake, or as an exemplar or paradigm case of a general phenomenon. In general, case study

research is concerned with the complexity and particular nature of the case in question, which may be: a

single organisation or institution; a single location; a person or group; a single intervention, initiative or

policy programme; or a single situation or event.]

There are two brief readings for you to consider. The first is a case study of a dissertation students

experience of researching in his uncles firm; the second is a collection of editorials and pieces that were

published in the wake of the criticisms levelled at the pharmaceutical MNC, GlaxoSmithKlien, in relation to

the suppression of negative findings from trials conducted for their anti-depressant drug, Seroxat.

Intended Learning Outcomes:

Following this tutorial, you should be able to:

consider research ethics as the exemplification of societys moral codes, rather than a bolt on

element of organizational/firm behaviour or additional element of research to be vicariously applied;

understand the main tenets of the case study approach to research.

Key Readings:

Tutorial Readings: Ethics in Research Case 1; Ethics in Research Case 2

Bryman & Bell pp.127-150

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill pp.183-209

Supplementary Readings:

Lindorff, M (2007) The Ethical Impact of Business and Organizational Research: The Forgotten

Methodological Issue? in The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 5:1 pp.21-28

http://www.ejbrm.com

Bell, E. & Bryman, A. (2007) The Ethics of Management Research: An Exploratory Content Analysis in

British Journal of Management

Academy of Management (2005) Code of Ethics

http://www.aomonline.org/governanceandethics/aomrevisedcodeofethics.pdf

14

Market Research Society (2010) Code of Conduct http://www.mrs.org.uk/standards/downloads/Code of

Conduct 2010.pdf

Social Research Association (2003) Ethical Guidelines http://www.admin@thesra.org.uk

Wiles, R., Heath, S., Crow, G. & Charles, V. (2005) Informed Consent in Social Research MCRM Methods

Review Papers NCRM001 ESRC: National Centre for Research Methods.

15

6. Critical Reading & Literature Reviews

Reviewing the literature critically will provide the foundation on which your research is built. Its main

purpose is to help you to develop a good understanding an insight into relevant previous research and the

trends that have emerged. Your review also has a number of other purposes:

to help you refine further your research question(s) and objectives;

to highlight research possibilities that have been overlooked implicitly in research to date;

to discover explicit recommendations for further research. These can provide you with a very good

justification for your own research question(s) and objectives;

to help you to avoid simply repeating work that has been done already;

to sample current opinions in newspapers, professional and trade journals, thereby gaining insights

into the aspects of your research question(s) and objectives that are considered newsworthy;

to discover and provide an insight into research approaches, strategies and techniques that may be

appropriate to your own research question(s) and objectives.

Critical reading entails evaluating the attempts of others to communicate with and convince their target

audience by means of developing a sufficiently strong argument. The skill of critical reading lies in

assessing the extent to which authors have provided adequate justification for the claims they make. This

assessment depends partly on what the authors have communicated and partly on other relevant

knowledge, experience and inference that you, as the critical reader, are able to bring into consideration.

The tutorial will introduce you to a set of Critical Synopsis Questions (Wallace & Wray, 2011) that you can

place against the literature you read. They are intended to provide a structure for ordering your critical

thoughts in response to any text, article or source that you read.

Intended Learning Outcomes

Following this tutorial, you should be able to:

understand the notion, rationale and process of a literature review;

use critical synopsis questions to order your critical thoughts on relevant literature for the purpose of

deciding a dissertation topic, and for your dissertation proposal literature review.

Key Readings

Bryman & Bell pp.74-91; 94-123 (available as PDF)

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill pp.58-68

Supplementary Readings:

Lepoutre, J & Heene, A (2006) Investigating the Impact of Firm Size on Small Business Social

Responsibility in Journal of Business Ethics 67 pp.257-273

Peredo, A-M & McLean, M (2006) Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review of the Concept in Journal of

World Business 41 pp.56-65

16

7. Literature Reviews for Proposals

This tutorial is intended as a follow-on from Tutorial 6. The literature review for your dissertation proposal

can be thought of as the first iteration of your dissertations critical literature review. As a preliminary study,

some proposal literature reviews will concentrate on some relevant literature, including news items; for

others, it may entail revisiting, clarifying or even reformulating their initial topic idea.

Importantly, for the proposal, the literature review is not only intended to be an initial review, analysis and

possible integration of relevant literature, but also where you must define and explain the concepts and/or

theory (or theories) that you intend to use/test/critique in your dissertation.

Intended Learning Outcomes

Following this tutorial, you should be able to:

be aware of the range of primary, secondary and tertiary literature sources available;

be able to identify key words and to undertake a literature search using a range of methods;

be able to evaluate the relevance and value to your proposal (and dissertation) of the literature you

find

Key Readings:

Bryman & Bell pp.94-123 (available as PDF)

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill pp.68-105

Supplementary Readings:

Armitage, A & Keeble-Allen (2008) Undertaking a Structured Literature Review or Structuring a Literature

Review in The Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6:2 pp.103-114 http://www.ejbrm.com

Page, D (2008) Systematic Literature Searching and the Bibliographic Database Haystack in The

Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6:2 pp.171-180 http://www.ejbrm.com

Bruce, C (2001) Interpreting the Scope of Their Literature Reviews: Significant Differences in Research

Students Concerns in New Library World 102:1163/1164 pp.158-165

17

8. Surveys and Questionnaire Design

Undertaking a survey is a popular and common strategy in business and management research and is

most frequently used to answer who, what, how much and how many questions. Survey, thus, tend to

be used for exploratory and descriptive research. The survey method provides a cheap and relatively easy

way to obtain a considerable amount of simply quantifiable data, which can be used to test and verify

hypotheses and identify further areas of research.

Survey designs have two defining features: (i) the form of the data and, (ii) the method of analysis.

Form of data: Surveys are based on the collection of data regarding the characteristics (variables) of cases

(units of analysis). Surveys produce a structured set of data that forms a variable-by-case grid. In the grid,

rows typically represent cases (e.g. people) and columns represent the characteristics of these cases, such

as gender (variables). Each cell in the grid contains information about a cases attribute on the relevant

variable (e.g. male).

Method of analysis: Descriptive analysis is simply achieved by counting and cross-tabulating the

distribution of attributes of variables from the variable by case grid. In particular, survey analysis involves

examining variation in the dependent variable (presumed effect) and selecting an independent variable

(presumed cause) that might be responsible for this variation.

Within business and management research, the greatest use of questionnaires is made within the survey

strategy. However, both experiment and case study research strategies can make use of questionnaires.

As a general term, questionnaire refers to all techniques of data collection in which each person is asked to

respond to the same set of questions in a predetermined order.

Your choice of questionnaire will be influenced by a variety of factors related to your own research

question(s) and objectives, and in particular the:

characteristics of the respondents from whom you wish collect data;

importance of reaching a particular person as respondent;

importance of respondents answers not being contaminated or distorted;

size of sample you require for your analysis, taking into account the likely response rate;

types of question you need to ask to collect your data;

number of questions you need to ask to collect your data.

Intended Learning Outcomes:

Following this tutorial, you should be able to:

understand the advantages and disadvantages of questionnaires as a data collection method;

be aware of a range of self-administered and interviewer-administered questions;

be able to select and justify the use of appropriate questionnaire techniques for a variety of research

scenarios;

be able to apply the knowledge, skills and understanding gained to your own research project.

Key Readings:

Bryman & Bell pp.208-279

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill pp.360-413

18

Supplementary Readings:

Faulkner, X & Culwin, F (2005) When Fingers Do the Talking: A Study of Text Messaging in Interacting

With Computers 17 pp.167-185

Tourangeau, R & Smith, T.W. (1996) Asking Sensitive Questions: The Impact of Data Collection Mode,

Question Format, and Question Context in Public Opinion Quarterly 60 pp.275-304

Lucas, R (1997) Youth, Gender and Part-Time Students in the Labour Process in Work, Employment

&Society 11:4 pp.595-614

19

9. Analysing & Interpreting Quantitative Data

Quantitative data need to be processed to make them useful specifically, to turn them into information.

Quantitative analysis techniques such as graphs, charts and statistics allow you to do this; helping you to

explore, present, describe and examine relationships and trends within the data.

For this tutorial exercise, Tukeys (1977) exploratory data analysis approach will be used. This approach

emphasises the importance of diagrams to explore and understand the data, emphasising the importance

of using the data to guide the choice of analysis techniques.

Intended Learning Outcomes:

Following this tutorial, you should be able to:

identify the main issues that you will need to consider when preparing quantitative data for analysis;

recognise different types of data and understand the implications of data type for subsequent

analysis;

select the most appropriate tables and diagrams to explore and illustrate different aspects of the

collected data

Key Readings:

Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill pp.414-478

Bryman & Bell pp.324-374

20

10. Interviews and Discussion Guide Design

Interviews are a method for collecting data at the individual level. Interviews may be structured, with the

interviewer asking set questions and the respondents replies being immediately categorised. Unstructured

interviews are desirable when the initial exploration of an area is being made, when hypotheses are being

generated, and when the depth of data required is more important than ease of analysis.

The most popular interview method is semi-structured, where the interviewer has a series of questions that

are in the general form of an interview schedule but is able to vary the sequence of questions. Also, the

interviewer will often make use of further questions (sometimes included in the interview schedule as

prompts) in response to what are seen as significant replies, or when further detail on a particular question

(or theme) is desirable.

The tutorial will focus on how each form of interview has a distinct purpose; the types of questions that you

can use during semi-structured interviews; and how to plan and prepare for conducting an interview with a

respondent.

Intended Learning Outcomes:

Following this tutorial, you should be able to:

classify research interviews in order to help you to understand the purpose of each type;

devise and use an interview guide for semi-structured interviewing;

consider the development of your competence to undertake semi-structured interviews, and the

logistical and resource issues that affect their use.

Key Readings:

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill pp.318-359

Bryman & Bell pp.471-508

Interviewing in Qualitative Research (PDF available on Xstream)

Bryman, A & Cassell, C (2006) The Researcher Interview: A Reflexive Perspective in Qualitative

Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal 1:1 pp.41-55

Holt, A (2010) Using the Telephone for Narrative Interviewing: A Research Note in Qualitative Research

10:1 pp.113-121

Hoong Sin, C (2005) Seeking Informed Consent: Reflections on Research Practice in Sociology 39:2

pp.277-294

Kvale, S (2006) Dominance Through Interviews and Dialogues in Qualitative Enquiry 12:3 pp.480-500

Willman, P., Fenton-OCreevy, M., Nicholson, N. & Soane, E (2002) Traders, Managers and Loss Aversion

in Investment Banking: A Field Study in Accounting, Organizations and Society 27 pp.85-98

Hoffmann, E.A. (2007) Open-Ended Interviews, Power, and Emotional Labour in Journal of Contemporary

Ethnography 36:3 pp.318-346

21

11. Analysing and Interpreting Qualitative Data

Qualitative data refers to all non-numerical data, or data that have not been quantified and can be a product

of all research strategies. Qualitative research very rapidly generates a large, unwieldy database because

of its reliance on prose in the form of interview transcripts, documents, and fieldnotes. It can range from a

short list of responses to open-ended questions in an online questionnaire to more complex data such as

transcripts of an interview or entire policy documents.

Data collection, data analysis and the development and verification of propositions are an interrelated and

interactive set of processes. Analysis occurs during the collection of data as well as after it. The interactive

nature of data collection and analysis allows you to recognise important themes, patterns and relationships

as you collect data. As a result, you will be able to re-categorise your existing data to see whether these

themes, patterns and relationships are present in the case where you have already collected data.

There are two main approaches to qualitative analysis:

the deductive approach based on the idea that hypotheses are essential in science, and where a

researcher deduces a hypothesis (from existing theory) that must be subjected to empirical scrutiny;

the inductive approach where theory is the outcome of research, and where the process of

induction involved drawing generalizable inferences out of observations.

The tutorial exercise will consider both approaches.

Intended Learning Outcome:

Following this tutorial, you should be able to:

identify the main issues you need to consider when preparing qualitative data for analysis;

discuss and use deductively-based and inductively-based analytical approaches to, and procedures

for, analysing qualitative data

Key Readings:

Saunders, Lewis and Thornhill pp.480-525

Bryman & Bell pp.578-601

22

12. The Dissertation Process

This final tutorial will review the dissertation process, paying particular attention to how best you can

understand and learn from the feedback your supervisor writes on drafts of your dissertation.

Intended Learning Outcome:

Following this tutorial, you should be able to:

understand the different types of feedback (oral or written);

recognise different examples of feedback and what they mean

Key readings:

Saunders, Lewis & Thornhill pp.526-560

23

The Module Assessment

3000-Word Dissertation Proposal

Preparing your dissertation proposal

STRUCTURE OF THE PROPOSAL

Your proposal should be structured under these key themes:

i) Working title of the dissertation;

ii) Introduction to the subject and why the topic is relevant;

iii) Initial literature review and theoretical framework(s);

iv) Research aims and objectives;

v) Terms of reference;

vi) Methodology to be used;

vii) Bibliography

It is important to remember that your proposal is not just a communication between you and your

supervisor; it is a valuable tool in a variety of ways. First, it helps you get your ideas in a clear structure

and to focus your research in order to be clear as to the direction and purpose of your work.

Second, it requires you to do some initial reading around the area, which can help you target your thinking

much more, provide a theoretical base for your work, uncover a piece of work that has conducted research

in your chosen area, and may well give you some ideas about what methodological approach to take.

Third, and importantly, your proposal will help you keep on track as you undertake the dissertation. A

proposal with clearly stated aims and objectives will prevent you wandering down blind alleys or cul-de-

sacs during your research and writing up.

i) Working Title

Your title should be a sentence which clearly communicates your topic of research. At the early stage try to

think of something short and succinct that provides a clear indication of the area of work. Also, try to

ensure your working title is focused you want the title to provide information to potential readers in order

that they can judge its potential relevance to them quickly and easily.

Finalising your title may well be something that you do once you have had the opportunity to fully establish

your Aims and Objectives; there should be a clear relationship between the two.

ii) Introduction/Context

This section will be where you provide the Introduction and Context for your dissertation, in order to

establish why it is relevant, important, and/or timely. It is also where you address where the idea for the

research began. Dissertations often arise through a personal interest in a topic, or in response to

something you may have observed in your own workplace or sector. These are perfectly valid reasons for

using the dissertation as a means of investigating a topic or issue in a more systematic manner.

However, it is equally important in your introduction/context section to draw on relevant existing literature

(e.g. policy documents, published research reports, theoretical texts) in order to establish the rationale for

your particular dissertation.

Thus, any literature you cite in this section, and the concepts and ideas briefly presented as context, will be

elaborated upon in the literature review section of your proposal.

24

Yet, it is very useful to establish in this section what contribution your research will make to existing

knowledge in this area. This may well seem a daunting prospect at this stage but it is important to

remember that you do not have to propose a new theory or claim a revolution in your topic area will result

from the findings of your project! A small contribution to knowledge is always a contribution to knowledge

nonetheless.

iii) Theoretical Framework/Initial Literature Review

This section should provide an overview of the existing literature in your chosen area. It therefore provides

context for your chosen topic and indicates how your research relates to the theories, themes and issues in

your field of study. Your focus here is to provide an overview but also an evaluation of the literature. It

requires more than simple description.

You should present a themed discussion of the material and, if applicable, identify any gaps in existing

research which provide further justification for your own research.

Writing a Literature Review is a creative exercise. You will have read around the topic and now need to

present your informed tour of the literature to those who will read your proposal. It is therefore important

to present the material in a structured way. This may involve mapping the history or development of a

concept or set of ideas in your topic area. You will also need to provide an assessment of current themes,

theories and, possibly, conflicts.

At the proposal stage, the literature review will be indicative in that you will not have enough time and

space at this stage for a thorough review. Whatever you complete at the proposal stage, however, will be

very valuable. It should ideally form the basis for your complete Literature Review at the writing-up stage

after you have finished your data gathering.

The objective here is to establish that you are aware of and understand the major issues in your chosen

field. The literature review also provides you with guidance as to the methods you may adopt in your

dissertation.

It may be, for example, that you wish to replicate a methodology already tried and tested; or you may feel

that a certain methodological approach has dominated research in your field and you therefore wish to

approach the subject differently.

iv) Aims and Objectives

Aims and Objectives are not always easy to write down particularly at the proposal stage. Translating

good research ideas into clear aims and objectives can be difficult and time-consuming. One good way to

help organise and focus your approach is to describe what your research is about to a friend or fellow

student. If you can communicate your ideas effectively, that can form the basis from which to develop a

more formal statement of Aims and Objectives.

Another useful way to approach this section is to consider your research in terms of a question, or set of

questions. What is it exactly that you want to examine? This question can then be re-worked as your aim.

Indeed, many research articles articulate both an aim and specify what questions are being explored in the

research.

Aims

Ideally, you should state your research aim in a sentence or perhaps two sentences. It should not,

however, be a long paragraph containing explanatory detail. If you find your research idea runs to more

than one or two sentences, then this is a clear indication that you need to focus down the general

statement of the research aim.

The aim should be a fairly general statement of what you intend to explore.

25

Objectives

Following on from the Aim, and related to it, should be a set of Objectives which can be listed in bullet

point form. The ideal here is to provide focus by narrowing down the general statement of the overall aim.

You can achieve this by thinking carefully through the exact issue you wish to address (e.g. a particular

company; a particular sector; a sample of users/customers; a certain timeframe; etc.).

The Objectives give an idea of the types of areas you will address within the dissertation. As a rough

guide, between three and seven Objectives is a sensible number.

However, do not be tempted at this stage to be too specific. A common error at the proposal stage is to

attempt a level of detail that is actually part of a later stage of the research such as developing individual

questions that might be asked in interviews or questionnaires.

You will also need to consider the relationship between the Aims and Objectives. Another common error at

the proposal stage is to concentrate on focusing the Aim and then inadvertently expanding the breadth of

the research remit by trying to cover too much in the Objectives.

An alternative to developing a set of Aims and Objectives is to establish a hypothesis a proposition that

you wish to test as the basis of your project.

v) Terms of Reference

It is best to consider the Terms of Reference as linked closely to the Aims and Objectives section. Your

terms of reference can be understood as, effectively, a list of supplementary or sub objectives that will

form much of the foundations on which your dissertation objectives will rest.

Put another way, whereas the Aims and Objectives focus on the exact issues that the project will address,

the Terms of Reference list what the main steps your project will take to achieve these Aims. For example:

The dissertation will be informed by (relevant concepts/theories) and the findings of the literature

review examining (e.g. customers or employees levels of satisfaction);

The dissertation will utilise primary research to survey (e.g. customers/employees about their levels

of satisfaction);

The dissertation will conclude by making specific recommendations as to how (e.g.

customer/employee levels of satisfaction can be increased).

Ethical Considerations

Your proposal should provide an account of any Ethical Considerations that are pertinent for your

dissertation. And you should be aware of the need to act in an ethical manner in the various stages of the

project:

Formulating the research questions;

Data collection (informed consent);

Confidentiality and/or anonymity when presenting results;

Storage/destruction of data at the end of the dissertation.

Undertaking research in health-related areas, for example, will often require you to comply with strict

National Health Service requirements. Some areas of research, such as working with children or

disadvantaged adults, also require a careful consideration of how the research can be conducted. In these

kinds of instances, the use of a gatekeeper is strongly advisable, as they can not only facilitate access to a

group of people or location, but can also vouch for you.

26

vi) Research Design and Methods

Your Research Design and choice of Methods should be dictated by your Aims and Objectives, and will

add detail to the elements listed in the Terms of Reference. Nevertheless, there will sometimes be

constraints on what you can do, particularly if you are carrying out non-funded research in your own

organisation. You need to think carefully about what approach you will adapt and which methods you will

use and why.

Will the selected methods be:

the most appropriate way of collecting the data?

feasible in terms of time and resources?

possible?

This section of your proposal should be informed by relevant readings about your chosen methods and you

should reference appropriate research methods literature. There are many good research methods

textbooks covering social science approaches to research and you will have been given some materials for

this purpose and an extensive reading list.

You should indicate specifically how your Methods relate to your Aims and Objectives, and why they are

appropriate for achieving them. You need to demonstrate an understanding of what your chosen methods

involve, and to indicate what some of the limitations might be. All research designs involve making

decisions about what method to adopt; what to include; what to leave out. This is inevitable. And as long

as your chosen method is appropriate for what you want to achieve, you will not be wrong in how you

approach your data gathering.

It is important, however, to be clear and honest about what you will do; how you will do it; and why. Be

clear about any limitations of your proposed approach. All research has limitations and if they are

acknowledged, it makes the task of judging the proposal much easier.

Research Design

Your overall Research Design relates to questions of methodology: is it appropriate to pursue a

quantitative, qualitative or mixed approach? Debates about quantitative versus qualitative approaches to

gathering and analysing data can become very detailed with no consensus in sight. Indeed, this

characterises much debate on the issue. You are not expected to resolve long-running debates. Just

consider what is likely to be the best way of gathering sufficient useful data for your project and be

prepared to reflect on the process.

What is important here is that the methods used are those that enable you to collect the data which can

answer your original questions. You may, for example, draw upon quantitative findings (results from

questionnaires; usage figures; official statistics; etc) and seek to explore qualitatively the meanings that

your chosen sample/population/cohort/person/organisation attach to some of the statistical information you

have studied.

Methods

Once you have decided upon your chosen strategy, you will need to select specific Methods for collecting

your data. This usually involves asking questions of systems, or texts, or people. At the proposal stage,

you need to communicate to the assessor that you have selected appropriate Methods. You also need to

provide an indication of how you will implement them.

If you intend to use questionnaires, you will need to indicate if these will be paper-based or online; and how

you intend to pilot and/or distribute them. If you intend to conduct interviews, will they be structured or

semi-structured? At the proposal stage, you do not need to come up with a completed questionnaire or

interview schedule (set of questions). But you should have some idea about the topics you will be

covering.

27

vii) List of References

All material texts, articles, reports, websites, media you have drawn on for your proposal must be cited

correctly in the main body of the proposal and the full reference must also be placed in a dedicate

Bibliography.

You should adopt the Harvard system of referencing both in the main body of your proposal and for your

Bibliography. You will have been given guidance about this before writing your proposal.

28

Dissertation Proposal Marking Criteria

CRITERIA < 40% 40 - 49% 50 - 59% 60 - 69% > 70%

Distinction Level

Project Rationale (20%)

Thorough, but concise overview of the problem/

issue under investigation, including why it is a

significant study and why/ how it may impact on

theory and/ or practice.

Aims, hypotheses/research questions, key

variables, and brief explanation of method included.

Not identified (0%)

OR

Major omissions to the

requirements as laid out

in the dissertations

guidelines.

An attempt has been

made, but some areas

may be missing or

lacking in substance.

All areas covered, but

some areas may be

weaker than others.

All areas covered, well-

articulated. It is clear what

the dissertation is about,

and why it is being

undertaken.

All areas covered to an

extremely high standard.

Literature review (30%)

Critical review, analysis and integration of the

relevant literature(s).

Review of past research.

Definition and explanation of concepts and

constructs.

Not addressed (0%)

OR

Descriptive in nature,

with many elements

which are not relevant to

the research questions.

Partially addressed,

although insufficient

literature considered and

this is not critically

analysed or integrated

into a coherent whole.

Sufficient literature

considered, some

attempt at analysis, but

lacking in critical focus

and only partially

integrated into a

coherent whole.

Extensive literature

considered and analysed,

good integration of

literature and some critical

content.

Overall critical review of

relevant and up-to-date

literature. Breadth and

depth of literature reviewed

is appropriate, and

integrated into a coherent

whole.

Research Design: (25%)

Appropriate choice, justification of method(s) and

methodology.

Not addressed (0%)

OR

Totally inappropriate,

inconsistent, confused

approach.

Choice of method would

work, but not necessarily

the most appropriate.

No/poor rationale given

for method(s).

Competent choice of

appropriate method(s).

A rationale is given for

the method(s), but this is

of an average standard,

requiring greater

explanation.

Good choice of

appropriate method(s)

under the identified

constraints of the study,

with clear, unambiguous

rationale given.

Excellent choice of

appropriate (even

innovative) method(s).

Robust justification, with

consideration of

implications.

29

CRITERIA < 40% 40 - 49% 50 - 59% 60 - 69% > 70%

Distinction Level

Project Plan: (15%)

Project management provision,

Consideration of ethical access, resource issues;

Ethics form included.

Not addressed (0%)

OR

No, or very little

discussion of project

plan. No consideration

of access, ethical and

resource management

issues.

Descriptive discussion

and/or limited project

plan. Inconsistent

consideration of access,

ethical and resource

management issues.

Some critical discussion

of a complete project

plan. Come thoughtful

consideration of access,

ethical and resource

management issues..

Good critical discussion of

a detailed project plan.

Methodical approach to

access, ethical and

resource management

issues.

Insightful critical discussion

of a thorough project plan.

Insightful and systematic

consideration of access,

ethical and resource

management issues.

Referencing, Presentation & Communication:

(10%)

Academic referencing, both throughout the script

and in the reference section using the Harvard style.

NB: a reference section was requested, NOT a

bibliography.

General writing style i.e. academic style and

adherence to required presentation.

Presentation of material, argument and structure

No referencing (0%).

OR

Poor or inconsistent

referencing throughout.

Lacking in academic

style, has not followed

the requirements, and/or

muddled structure.

Some referencing, but

patchy e.g. many

instances where

references are required.

Reference section may

be attempted, but

contains errors, and

some may be missing.

Style is generally poor,

presentation needs

improvement, and

unclear structure.

Satisfactory referencing

throughout, with some

errors or missing

references; generally

sound.

Inconsistent style i.e.

some parts better than

others and clear

structure

Good referencing, with the

occasional error or

missing references.

Good academic style,

presentation and clear and

sensible structure.

Excellent, precise

referencing throughout.

Excellent academic style

and pristine presentation

and structure (as laid out in

the requirements).

30

Reading List

All of the texts listed below are available from the Civic Quarter and Headingley Campus libraries.

Whilst Xstream provides an extensive set of central learning resources, students should contact

their tutor for advice on contextually relevant texts and/or journal articles.

There are some general texts offering help and advice with regards to dissertation preparation and

writing. Among the best of these are:

Lomas, R (2011) Mastering Your Business Dissertation: How to Conceive, Research and Write a Good

Business Dissertation London: Routledge

Fisher, C.M. (2010) Researching and Writing a Dissertation: An Essential Guide for Business Students

Harlow: FT/Prentice Hall

Biggam, J (2008) Suceeding With Your Masters Dissertation: A Step-by-Step Handbook Maidenhead:

Open University Press

Brown, R (2006) Doing Your Dissertation in Business & Management: The Reality of Research and Writing

London: Sage

Fisher, C.M. & Buglear, J (2004) Researching and Writing a Dissertation for Business Students London:

Sage

White, B (2003) Dissertation Skills for Business and Management Students London: Continuum

White, B (2002) Writing Your MBA Dissertation London: Continuum

Riley, M (2000) Researching and Writing Dissertations in Business and Management London: Thomson

Learning

White, B (2000) Dissertation Skills for Business and Management Students London: Cassell

There are a large number of texts available which offer Postgraduate students an introductory

insight into Research Methods. For example:

Bryman, A. & Bell, E. (2007) Business Research Methods (2

nd

ed) Oxford: University Press

Saunders, M.N.K., Lewis, P. & Thornhill, A. (2009) Research Methods for Business Students (5th ed.)

Harlow: FT Prentice Hall

Quinton, S. & Smallbone, T. (2006) Postgraduate Research in Business: A Critical Guide London: Sage

Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R. & Lowe, A. (2002) Management Research: An Introduction (2

nd

ed) London:

Sage

Sekaran, U. (2003) Research Methods for Business: A Skills-Building Approach Hoboken: John Wiley &

Sons

Alvesson, M. & Deetz, S. (2000) Doing Critical Management Research London: Sage

31

Gill, J. & Johnson, P. (2002) Research Methods for Managers (3

rd

ed) London: Sage

Remenyi, D., Williams, B. Money, A. & Swartz, E. (1998) Doing Research in Business and Management:

An Introduction to Process and Method London: Sage

Bryman, A. (2004) Social Research Methods Oxford: University Press

Burns, R.B. (2000) Introduction to Research Methods London: Sage

Brewerton, P. & Millward, L. (2001) Organisational Research Methods: A Guide for Students and

Researchers London: Sage

Ghauri, P., Grnhaug, K. & Kristianslund, I. (1995) Research Methods in Business: A Practical Guide

Hemel Hempstead: FT Prentice Hall

However, postgraduate students should use sources that offer more specialist guidance wherever

possible. The following texts illustrate the depth and scope expected at postgraduate level

Keegan, S (2009) Qualitative Research: Good Decision Making Through Understanding People, Cultures

and Markets London: Kogan Page

Johnson, P. & Duberley, J. (2000) Understanding Management Research: An Introduction to Epistemology

London: Sage

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (2005) The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research (3

rd

ed) London: Sage

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (2003) Collecting and Interpreting Qualitative Materials Thousand Oaks: Sage

May, T (ed) (2002) Qualitative Research in Action London: Sage

Silverman, D (2005) Doing Qualitative Research: A Practical Handbook London: Sage

Silverman, D (2006) Interpreting Qualitative Data: Methods for Analysing Talk, Text and Interaction London:

Sage

Hardy, M. & Bryman, A. (eds) (2004) Handbook of Data Analysis London: Sage

Mariampolski, H (2001) Qualitative Market Research Thousand Oaks: Sage

Chrzanowska, J (2002) Interviewing Groups and Individuals in Qualitative Market Research London: Sage

Ereaut, G., Imms, M. & Cllingham, M. (eds.) (2002) Qualitative Market Research: Principle and Practice

London: Sage

Balnaves, M. & Caputi, P. (2001) Introduction to Quantitative Research Methods: An Investigatory

Approach London: Sage

Morris, C (2003) Quantitative Approaches in Business Studies Harlow: Pearson

Black, T (1999) Doing Quantitative Research in the Social Sciences: An Integrated Approach to Rsearch

Design, Measurement and Statistics London: Sage

Hackett, G. & Caunt, D. (1994) Quantitative Methods: An Active Learning Approach Oxford: Blackwell

Denscombe, M (2002) The Good Research Guide for Small-Scale Social Research Projects Buckingham:

Open University Press

32

Coghlan, D. & Brannick, T. (2005) Doing Action Research in Your Own Organisation London: Sage

Hart, C (2002) Doing a Literature Review London: Sage

Arksey, H. & Knight, P. (1999) Interviewing for Social Scientists: An Introductory Resource with Examples

London: Sage

Megrove, C. & Robinson, S.J. (2002) Case Histories in Business Ethics New York: Routledge

Oliver, P (2003) The Students Guide to Research Ethics Maidenhead: Open University Press

Barry, N (1998) Business Ethics Basingstoke: Macmillan Business

Chryssides, G.D., & Kaler, J.H. (1993) An Introduction to Business Ethics London: International Thomson

Business Press

Donaldson, J (1992) Business Ethics: A European Casebook London: Academic Press

Gray, D.E. (2004) Doing Research in the Real World London: Sage

Pole, C. & Lampard, R. (2002) Practical Social Investigation Harlow: Pearson Education

Robson, C (2002) Real World Research Oxford: Blackwell

You might also like

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- JCB Service Data Book 1992 On PDFDocument1,890 pagesJCB Service Data Book 1992 On PDFDavid Solis67% (6)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Seat Belt Reminder Knee Protection For Driver Alarm & Immobiliser Seat Belts With Pretensioners & Load LimitersDocument2 pagesSeat Belt Reminder Knee Protection For Driver Alarm & Immobiliser Seat Belts With Pretensioners & Load LimitersbdsisiraNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- 0417 - 02 Igcse Ict November 2017Document5 pages0417 - 02 Igcse Ict November 2017bdsisiraNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- 2020 Specimen Paper 4Document18 pages2020 Specimen Paper 4bdsisiraNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Lubricants Comparision Between Brands PDFDocument6 pagesLubricants Comparision Between Brands PDFbdsisiraNo ratings yet

- Cfs0018 UK R1 Menvier-Product-CatalogueDocument112 pagesCfs0018 UK R1 Menvier-Product-CatalogueABELWALIDNo ratings yet

- Speciman Paper 1Document16 pagesSpeciman Paper 1bdsisiraNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- GET-122CR Total Station Brochure - GeodexDocument2 pagesGET-122CR Total Station Brochure - Geodexbdsisira100% (1)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Easy Ups 3s E3sups10kh ApcDocument2 pagesEasy Ups 3s E3sups10kh ApcbdsisiraNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- ACCA SyllabusDocument6 pagesACCA SyllabusbdsisiraNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Smart Grids - SolarDocument21 pagesSmart Grids - SolarbdsisiraNo ratings yet

- Easy Ups 3s E3sups10kh ApcDocument2 pagesEasy Ups 3s E3sups10kh ApcbdsisiraNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Comprehensive Building Information Management System ApproachDocument17 pagesComprehensive Building Information Management System ApproachbdsisiraNo ratings yet

- mf16 19Document4 pagesmf16 19bdsisiraNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Dynalite Control Products Catalogue 2006Document13 pagesDynalite Control Products Catalogue 2006bdsisiraNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- DTK622Document2 pagesDTK622bdsisiraNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- ZigbeeRG2017 2Document32 pagesZigbeeRG2017 2bdsisiraNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Cfs0018 UK R1 Menvier-MF9300 RangeDocument4 pagesCfs0018 UK R1 Menvier-MF9300 RangebdsisiraNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- GSEP-EMWG Energy Management in Cities June2014Document16 pagesGSEP-EMWG Energy Management in Cities June2014bdsisiraNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Best Practices For Securing An Intelligent Building Management SystemDocument16 pagesBest Practices For Securing An Intelligent Building Management SystembdsisiraNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Rando HD: Premium Anti-Wear Hydraulic FluidDocument2 pagesRando HD: Premium Anti-Wear Hydraulic FluidbdsisiraNo ratings yet

- Lubrificantes 2Document3 pagesLubrificantes 2skyNo ratings yet

- Cynthia Cover Pag (Acc)Document12 pagesCynthia Cover Pag (Acc)Faith MoneyNo ratings yet

- BBA III StatisticSDocument11 pagesBBA III StatisticSSuresh Kumar JhaNo ratings yet

- E-Crm Features and E-LoyaltyDocument238 pagesE-Crm Features and E-LoyaltyDouglas Percy White R.0% (1)

- Serranillo Chapter 1 5 12 IDocument50 pagesSerranillo Chapter 1 5 12 IKal El AndayaNo ratings yet

- Descriptive Research - Tampocao&cerilo R.Document66 pagesDescriptive Research - Tampocao&cerilo R.Jelyn MamansagNo ratings yet

- Hospital Planning and Project ManegmentDocument160 pagesHospital Planning and Project ManegmentSatarupa Paul ChoudhuryNo ratings yet

- A Project Report On Sales of Videocon Products With Special Referance TODocument47 pagesA Project Report On Sales of Videocon Products With Special Referance TOShresth SinghNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Module 4. Market Research PRE-TEST: Before Starting With This Module, Let Us See What You Already Know About MarketDocument8 pagesModule 4. Market Research PRE-TEST: Before Starting With This Module, Let Us See What You Already Know About MarketJuanita Cabigon75% (4)

- The Validity of Surveys Online and OfflineDocument13 pagesThe Validity of Surveys Online and OfflineBuburuz CarmenNo ratings yet

- Project Report On Personal Loan CompressDocument62 pagesProject Report On Personal Loan CompressSudhakar GuntukaNo ratings yet

- Norton, Herek - 2013 - Heterosexuals' Attitudes Toward Transgender People Findings From A National Probability Sample of U.S. Adults PDFDocument17 pagesNorton, Herek - 2013 - Heterosexuals' Attitudes Toward Transgender People Findings From A National Probability Sample of U.S. Adults PDFDan22212No ratings yet

- Revised Research PaperDocument45 pagesRevised Research PaperNecole Ira BautistaNo ratings yet

- LQAS ValadezDocument16 pagesLQAS ValadezCESAR MONo ratings yet

- 5 10 pp.62 66Document6 pages5 10 pp.62 66timesave240No ratings yet

- What Influences Consumer Choice of Fresh Produce Purchase Location?Document14 pagesWhat Influences Consumer Choice of Fresh Produce Purchase Location?Divya PunjabiNo ratings yet

- Towards A Comprehensive Community-Based Model Against Malnutrition - MP Baseline Report 2013Document43 pagesTowards A Comprehensive Community-Based Model Against Malnutrition - MP Baseline Report 2013Vikas SamvadNo ratings yet

- Chapter 03 MMDocument38 pagesChapter 03 MMBappy PaulNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Survey Dissertation PDFDocument6 pagesSurvey Dissertation PDFPayToWritePapersSingapore100% (1)

- Supply Chain Localization Strategies For The FutureDocument162 pagesSupply Chain Localization Strategies For The FutureConstantine CucciNo ratings yet

- Q3 - Does Technology Orientation Predict Firm Performance Through Firm InnovativenessDocument14 pagesQ3 - Does Technology Orientation Predict Firm Performance Through Firm Innovativenesstedy hermawanNo ratings yet

- Project On ToothpasteDocument31 pagesProject On ToothpasteRoyal Projects89% (27)

- Challenges Faced by Working Mothers A Research Proposal4-1Document24 pagesChallenges Faced by Working Mothers A Research Proposal4-1بشير حيدرNo ratings yet

- Consumer Behaviour Project WorkDocument10 pagesConsumer Behaviour Project WorkDivyabhan SinghNo ratings yet

- A Study of Teacher Perceptions of Instructional Technology Integration in The Classroom PDFDocument15 pagesA Study of Teacher Perceptions of Instructional Technology Integration in The Classroom PDFfanaliraxNo ratings yet

- 2-Concordance of End-of-Life Care With End-of-Life WishesDocument12 pages2-Concordance of End-of-Life Care With End-of-Life WishesLucia HelenaNo ratings yet

- Related Factors of Actual Turnover Among Nurses: A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument7 pagesRelated Factors of Actual Turnover Among Nurses: A Cross-Sectional StudyIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Cultural Factors That Affect The TechnicDocument7 pagesCultural Factors That Affect The TechnicmattrhaierNo ratings yet

- Classification of Test According To FormatDocument4 pagesClassification of Test According To Formataldin gumela75% (4)

- Salahuddin Said 1211571 Research DesignDocument2 pagesSalahuddin Said 1211571 Research DesignSalahuddin SaidNo ratings yet

- Research Lecture 1Document19 pagesResearch Lecture 1Janna Mari FriasNo ratings yet

- Summary of Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the FutureFrom EverandSummary of Zero to One: Notes on Startups, or How to Build the FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (100)

- SYSTEMology: Create time, reduce errors and scale your profits with proven business systemsFrom EverandSYSTEMology: Create time, reduce errors and scale your profits with proven business systemsRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (48)

- The Millionaire Fastlane, 10th Anniversary Edition: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeFrom EverandThe Millionaire Fastlane, 10th Anniversary Edition: Crack the Code to Wealth and Live Rich for a LifetimeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (90)

- 12 Months to $1 Million: How to Pick a Winning Product, Build a Real Business, and Become a Seven-Figure EntrepreneurFrom Everand12 Months to $1 Million: How to Pick a Winning Product, Build a Real Business, and Become a Seven-Figure EntrepreneurRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)