Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Interim Relief Arbitration

Uploaded by

arjun3394Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Interim Relief Arbitration

Uploaded by

arjun3394Copyright:

Available Formats

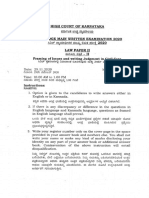

INTERIM RELIEF UNDER SECTION 9 OF THE ARBITRATION

AND CONCILIATION ACT, 1996

SEMINAR PAPER ON ARBITRATION LAWS

SUBMITTED BY

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

VIKAS KUMAR

BLI 976

NATIONAL LAW SCHOOL OF INDIA UNIVERSITY

BANGALORE

TRIMESTER XII

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 2 of 42

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

TABLE OF CASES..............................................................................................3

Introduction........................................................................................................ 5

Methodology.......................................................................................................7

Chapter I: Interim Orders under section 9 of the Act.......................................8

Chapter II........................................................................................................... 11

Chapter III

THE NATURE OF RELIEF AS PROVIDED UNDER SECTION

9 OF THE ACT

20

Chapter IV: Interim Orders in Foreign Arbitration......................................34

CHAPTER V:

CONCLUSION.........................................................................42

BIBLIOGRAPHY...............................................................................................44

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 3 of 42

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

TABLE OF CASES

Alpine Industries v. Union of India, (1988) 1 Arb LR 363 Delhi.

Anton Piller K.G. v. Manufacturing Processes Ltd., (1976) Ch 55.

Ashok Chazvia v. Rakesh Gupta, (1996) 2 Arb LR 255 (Delhi).

Banwari Ial Radhey.Mohan v. Punjab State Co-op Supply and Mktg Fedn.

Ltd., AIR 1983 Delhi 402.

Bhatia International v. Bulk Trading S.A. and Anr., MANU/SC/0185/2002.

Binny Ltd. v. Nizam sugars Ltd, (1997) 88 Comp Case 741 at 746 (AP).

Chandu Lot v. Brit-over Ltd., 52 CWN 451.

Channel Tunnel Group Ltd. v. Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd., 1993 1 All ER

664 at 683

Coppee-Lavalin SA/NV v. Ken-Ren Chemicals and Fertilizers Ltd. (in

Liquidiation) (1994) 2 All E.R. 449 at 466 HL.

Coppie-Levalin SA/NV v. Ken-Ren Chemicals and Fertilizers Ltd, [1994] 2 All

E.R. 449.

East Coast Shipping Ltd. v. M.J. Scrap Pvt. Ltd., AIR 1997 Cal 168.

Food Corporation of India v. P. A. Ahammed lbrahim, (1989) 1 Ker LT 251.

Global Co. v. National Fertilizers Ltd, AIR 1998 Delhi 397 at 400.

Gokuldas v. Union of India, Al R 198:3 Ker 169.

H.M. Kamatuddin Ansari & Co. v. Union of India., AIR 1984 SC 29.

Harbhajan Singh Kaur v. Unimode Finance, (1997) 2 Cal LT 414.

Hindustan Steel Works Construction Lid. v. Tarapore & Co., (1996) 87 Comp

Case 344.

I.M. D. Syndicate v. L T Commr. New Delhi, AIR 1977 SC 1348.

Keventer Agro Ltd. v. Seagram Co. Ltd, AIR 1997 Cal 200.

Marriott

International

Inc.

&

Ors.v.

Ansal

Hotels

Limited

&

Anr,

MANU/DE/0013/2000.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 4 of 42

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Mohinder Singh & Co. v. Executive Engineer, AIR 1971, J&K 130.

MVR Industries Ltd. v. Tribal Coop Mkg Development Federation of India

Ltd., (1996) 1 Arb 1,R 393 (Delhi).

MVR Industries Ltd. v. Tribal Coop Mkg Development Federation of India

Ltd., (1996) 1 Arb LR 393 (Delhi).

N.C. Bhall v. R.C. Bhalla (1990) 2 Arb.L.J. Delhi.

Narain Sahai Agrawal v. Santosh Rani, AIR 1998 Delhi 144.

National Building Construction Corpn. Ltd. v. IRCON Intl Ltd., (I998) 1 Raj

500

National Thermal Power Corpn Ltd. v. Flowmore P Ltd., AIR 1996 SC 445.

NEPC India Ltd v. Sundaram Finance Ltd, (1998) 2 Arb. LR 446 (Mad).

Newabgani Sugar Mills Co. lid. v. Union of India, AIR 1976 SC 1152.

R. K. Associates v. V Channappa, AIR 1993 Kant 247.

Ranjit Chandra Mitter v. Union of India, AIR 1963 Cal 594.

Rawla Constructions v. Union of India, AIR 1977 Delhi 205.

Roussel-Uclaf v. CD. Searle C5 Co. Ltd and G. D. Searle & Co. [1978] 1

Lloyd's Rep. 225

Sha Vaktavarmal Sheshmull v. Nainmull Umaji & Co., AIR 1962 Mad 436.

Subhash Chander Kakkar v. D. S. I. D. C., (1990) 2 DLT 21.

Sundaram Finance Ltd. v. NEPC India Ltd., (1999) 1 SLT 179 (SC)(1999).

Sundarlal Haveliwala v. Bhagwati Devi, AIR 1967 All, 400.

Taj Builders v. Indore Development Authority, AIR 1985 MP 146.

Tudor Accumulator Co. v. China Mutual, etc. Co., (1930) WN 201.

Union of India v. Om Construction and Supply Co., AIR 1994 All 334.

Union of India v. Raman Iron Foundry, (1974) Supp SCC 556 at pp. 561.

Vashdev Bheroomal Pamnani v. M. Bipin Kumar, AIR 1987 Bom 226.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 5 of 42

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 6 of 42

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Introduction

An arbitration agreement is a contractual undertaking by which the parties

agree to settle certain disputes by way of arbitration rather than by proceedings in

court. When a dispute arises however one of the parties may nevertheless

commence court proceedings either because he challenges the existence or validity

of the arbitration agreement or because he means to breach it.

This paper dwells therefore on the issues arising when a party approaches the

courts for interim measures.

Article 9 relates to the recognition and effect of the arbitration agreement by

laying down the principle, disputed in some jurisdictions, that resort to a court and

subsequent court action with regard to interim measures of protection are compatible

with an arbitration agreement. It must be accepted that negative effect of an arbitration

agreement, which is to exclude court jurisdiction, does not operate with regard to such

interim measures. The main reason being that the availability of such measures is not

contrary to the intentions of parties agreeing to submit a dispute to arbitration and the

measures themselves are conducive to making arbitration efficient and to securing its

expected results.

The critical question with regard to interim relief in arbitration is Who provides

interim measures of protection? Shall it be the courts, the arbitrators or both?

The answers given in national arbitration legislation and in arbitration rules have

changed over the years. Some time ago it seemed to be a common understanding that

only courts provide any provisional relief. This was reflected in international instruments

such as the 1961 European Convention on International Commercial Arbitration which

in Article VI, paragraph 4 stated that a request for interim measures to the courts is not a

waiver of the arbitration agreement. Similar provisions are found in arbitration rules.

They ensure that a party can have recourse to the courts without fearing to chance the

track of dispute settlement by making such an application. No mention was made of an

arbitrator's competence to grant interim measures of protection. However, later, a trend

in favor of such an arbitrator's competence emerged. This was first reflected in

arbitration rules such as the 1976 UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules for International

Commercial Arbitration (henceforth UNCITRAL Rules), which provide for a choice of

application. Article 26, paragraph 3 of the UNCITRAL Rules refers to court applications

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 7 of 42

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

and deems them to be compatible with the arbitration agreement. This reiterates the

established view. But in paragraphs 1 and 2 of the article, the UNCITRAL Rules go

further when making clear that arbitrators have contractual power to order certain special

kinds of interim measures such as the sale of perishable goods.

However, it is unfortunate that neither the New York Convention of 10 June 1958

on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (henceforth New York

Convention) nor any other international instrument deals with interim measures of

protection granted by the arbitrator or their enforcement. Probably the solution might be

concretely provided suitably only by national legislation by providing decisive provisional

remedies namely within the framework of court assistance, fall-back statutory

provisions and laying down the preconditions for the enforcement of arbitrator-granted

interim measures of protection.

The issue in interim order further gets complicated when the interim measures

are sought against International arbitrations or when the seat of arbitration falls outside

the country where interim relief is sought. This issue is of considerable importance in

India due to the conflicting judgements by various High Courts. Though the Supreme

Court in India has decided this question finally yet it raises quite interesting propositions

and is worth examining.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 8 of 42

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

METHODOLOGY

The topic of this seminar paper is Interim Relief under Section 9 of the

Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (henceforth referred to as the Act) and

accordingly dwells upon some of the various issues raised in the context of grant of

interim orders by the courts with regard to the contractual disputes wherein the

agreement also provides for a settlement through arbitration proceeding.

The introduction to the paper provides the background to the concept of

arbitration as has evolved in the jurisprudential framework, with regard to the specific

needs of the commercial world.

This seminar paper then broadly discusses the general law regarding interim

orders given by the national courts, as contemplated under the Act. This section is

illustrative in nature and brings out the various instances gleaned from the case laws.

This paper also compares the position of English law in this regard. The scope

and the ambit of the English law are of considered significance, since both the Indian

and the English laws of arbitration are based on the UNCITRAL model law on arbitration.

The last important section dwells upon the existing controversy in the Indian

courts, on the point whether the national courts in India have the jurisdiction to grant

interim orders with regard to foreign arbitral proceedings.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 9 of 42

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Chapter I: Interim Orders under section 9 of the Act.

The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (Act) has provisions enabling a party to

the arbitral proceeding to approach the court to request for interim measures.

S.9. Interim measures, etc. by court - A party may before, or during arbitral

proceedings or at any time after the make the arbitral award but before it is enforced

in accordance with section 36, apply to a court-

(i)

for the appointment of a guardian for a minor or a person of unsound mind

for the purposes of arbitral proceedings; or

(ii)

for an interim measure of protection in respect of any of the following

matters, namely:

(a) the preservation, interim custody or sale of any goods which are the

subject-matter of the arbitration agreement;

(b) securing the amount in dispute in the arbitration;

(c) the detention, preservation or inspection of any property or thing which is

the subject-matter of the dispute in Arbitration, or as to which any

question may arise therein and authorising for any of the aforesaid

purposes any person to enter upon any land or building in the possession

of any party, or authorizing any samples to be taken or any observation to

be made, or experiment to be tried, which may be necessary or

expedient for the purpose of obtaining full information or evidence;

(d) interim injunction or the appointment of a receiver;

(e) such other interim measure of protection as may appear to the court to

be just and convenient,

and the Court shall have the same power for making orders as it has for the

purpose of, and in relation to, any proceedings before it.

The analogous provision on the court's power to grant interim measures of

protection is contained in Article 9 of the Model Law which provides that

Article 9.

Arbitration agreement and interim measures by court.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 10 of 42

10

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

It is not incompatible with the arbitration agreement for a party to

request before or during arbitral proceedings, from a court an

interim measure of protection and for a court to grant such

measure.

Article 9 lays down the principle, which has been contested in some national

jurisdictions, that resort to a court and a subsequent court action in respect of

interim measures of protection are compatible with an arbitration agreement.

Thereby, clarifying that effect of an arbitration agreement, which is to exclude court

jurisdiction, does not operate negatively in respect to such interim measures. The

chief reason is that the availability of such measures is not contrary to the intentions

of parties agreeing to submit a dispute to arbitration and that the measures

themselves are conducive to making the arbitration efficient and to securing its

expected results.1

The range of interim measures of protection covered by article 9 is of

considerable wider ambit than provided under article 17 2 of the Model Law, that

deals with the limited power of the arbitral tribunal to order any party to take an

interim measure of protection in respect of the subject matter of the dispute without

dealing with issues of the enforcement of such orders. It is to be observed that the

model law is silent about the possible conflict between an order by the arbitral

tribunal under article 17 and a court decision under article 9 relating to the same

object or measure of protection. However, it is submitted that there is little potential

for such conflict in view of the disparity of the range of measures covered by the two

articles.

The UNCITRAL commentary on Model law provides that article 9 itself does

not regulate which interim measures of protection were available to a party. It

merely expresses the principle that a request for any court measure available under

1It has been commented by authorities like Russell that,

Article 9 expresses the principle of compatibility in two directions with different scope of

application. According to the first part of the provision, a request by a party for any such court

measures is not incompatible with the arbitration agreement, i.e., neither prohibited nor to be

regarded as a waiver of the agreement. This part of the rule applies irrespective of whether

the request is made to a court of State X or of any other country. Wherever it may be made, it

may not be invoked or created as an objection against or disregard of, a valid arbitration

agreement under this Law, i.e., in arbitration cases falling within its territorial scope of

application or in the context of articles 8 and 36.

However, the second part of the provision is addressed only to the courts of State X and declares their

measures to be compatible with the arbitration agreement irrespective of the place of arbitration.

Assuming wide adherence to the model law, these two parts of the provision would supplement each

other and go a long way towards global recognition of the principle of compatibility, which, in the

context of the 1958 New York Convention, has not been uniformly accepted.

2Article 17. Power of arbitral tribunal to order interim measures

Unless otherwise agreed by the parties, the arbitral tribunal may, at the request of a party, order any party to

take such interim measure of protection as the arbitral tribunal may consider necessary in respect of the

subject-matter of the dispute. The arbitral tribunal may require any party to provide appropriate security in

connection with such measure.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 11 of 42

11

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

a given legal system the granting of such measure by a court of this State was

compatible with the fact that the parties had agreed to settle their dispute by

arbitration.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 12 of 42

12

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Chapter II

PART A:SCOPE OF SECTION 9 OF THE ACT

The scope of the section was examined in a vast survey of cases and

authorities by the Madras High Court in NEPC India Ltd v. Sundaram Finance Ltd.3

This case arose out of a hire-purchase transaction, which carried an arbitration

clause and the buyer defaulted with an installment. The owner moved the court and

obtained an order under S. 9, without resort to the arbitration clause, for direct

seizure of the machinery with the help of police. The order was set-aside in an

appeal against it.

The Madras High Court was of the view that a request for

arbitration for substantive relief should be there before S. 9 could be used for interim

relief whether or not an arbitrator has been appointed or proceedings commenced

and not before that.

In another case, Harbhajan Singh Kaur v. Unimode Finance, (1997) 2 Cal LT

414, the Court observed as follows

Clause (ii) to section 9(a) of the said Act begins with a prefix, namely, for an

interim measure of protection in respect of the measures that may be

taken by the court and the same are catalogued in Clauses (a) to (d) of

section 9(ii) of the Act. The court is made to ponder over the proposition

used in the expression 'interim measure' by insertion of 'an' and, at the same

time, a catena of matters has been elicited thereunder. The expression used

is in the midst of pendency of an arbitral proceeding in between making of

the arbitral award and enforcement in accordance with section 36.

Therefore, the expression an is one of the alternative; and it has to be rated

as in the midst of possibility of many during the pendency of an arbitral

proceeding as indicated in section 9 itself.

This decision of the Madras High Court was reversed by the Supreme Court

on appeal Sundaram Finance Ltd. v. NEPC India Ltd., 4 where the Supreme Court

held that the court has jurisdiction under Section 9 to pass interim orders even

3 (1998) 2 Arb. LR 446 (Mad) To the same effect was National Building Construction Corpn.

Ltd. v.

IRCON Intl Ltd., (I998) 1 Raj 500, 543 that foundation for arbitration must be laid before claiming relief

under S.2. An interim measure cannot be provided where there is no prayer for some substantive relief,

Ashok Chazvia v. Rakesh Gupta, (1996) 2 Arb LR 255 (Delhi).

4(1999) 1 SLT 179 (SC)1999) 1 JT 49 (SC)

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 13 of 42

13

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

before the commencement of arbitration proceedings and appointment of arbitrator.

All that sufficed was that there must be satisfaction on the part of the court that the

applicant will take effective steps for commencing arbitral proceedings. This was

reflected in the following passage in the judgment5 When a party applies under Section 9 of the 1996 Act it is implicit that it

accepts that there is a final and binding arbitration agreement in existence. It

is also implicit the a dispute must have arisen which is referable to the

Arbitral Tribunal Section 9 further contemplates arbitration proceedings

taking place between the parties when an application under Section 9 is filed

before the commencement of the arbitral proceedings there has to be

manifest intention on the part of the applicant to rake recourse to the arbitral

proceedings if, at the time when the application under Section 9 is filed, the

proceedings have not commenced under section 21 of the 1996 Act. In

order to give full effect to the words before or during arbitral proceedings

occurring in Section 9 it would not be necessary that a notice invoking the

arbitration clause must be issued to the opposite party before an application

under Section 9 can be filed. The issuance of a given case of a notice may

be sufficient to establish the manifest intention to have the dispute referred to

arbitral Tribunal but a situation may so demand that a party may choose to

apply under Section 9 for an interim measure even before issuing a notice

contemplated by Section 21 of the said Act. If an application is so made the

Court will first have to be satisfied that there exists a valid arbitration

agreement and the applicant intends to take the dispute to arbitration. Once

it is so satisfied the Court will have the jurisdiction to pass orders under

Section 9 giving such interim protection as the facts and circumstances

warrant. While passing such an order and in order to ensure that effective

steps are taken to commence the arbitral proceedings, the Court while

exercising jurisdiction under Section 9 can pass conditional order to put the

applicant to such terms as it may deem fit with a few to see that effective

steps are taken by the applicant for commencing the arbitral proceedings.

What is apparent, however, is that the Court is not debarred from dealing

with an application under Section 9 merely because no notice has been

issued under Section 21 of the 1996 Act.

Referring to the support, which the Madras High Court in NEPC India Ltd v.

Sundaram Finance Ltd.6 had drawn from the 1940 Act in interpreting the 1996 Act,

the Supreme Court said7-

5 (1999) 1 SLT at p. 180 (SC).

6 (1998) 2 Arb. LR 446 (Mad) To the same effect was National Building Construction Corpn.

Ltd. v.

IRCON Intl Ltd., (I998) 1 Raj 500, 543 that foundation for arbitration must be laid before claiming relief

under S.2. An interim measure cannot be provided where there is no prayer for some substantive relief,

Ashok Chazvia v. Rakesh Gupta, (1996) 2 Arb LR 255 (Delhi).

(1991) 1 SLT at pp. 185, 188-189 (SC).

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 14 of 42

14

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

The 1996 Act is very different from the Arbitration Act, 1940. The provisions

of this Act have; therefore, to be interpreted and construed independently

and in fact reference to 1940 Act may actually lead to misconstruction. In

other words, the provisions of 1996 Act have to be interpreted being

uninfluenced by the principles underlying the 1940 Act. In order to get help

in construing these provisions it is more relevant to refer to the UNCITRAL

Model Law rather than the 1940 Act.

Section 9 of the said Act corresponds to article 9 of the UNCITRAL model

Law, this article recognizes, just like Section 9 of the 1996 Act, a request

being made before a Court for an interim measure of protection before

arbitral proceedings. It is possible that in some countries if a party went to

the Court seeking interim measure of protection that might be construed

under the local law as meaning that the said party had waived its right to take

recourse to arbitration. Article 9 of the UNCITRAL Model law seeks to clarify

that merely because a party to an arbitration agreement requests the Court

for an interim measure before or during arbitral proceedings such recourse

would not be regarded as being incompatible with an arbitration agreement.

To put it differently the arbitration proceedings can commence and continue

not with standing one party to the arbitration agreement having approached

the Court for an order for interim protection. The language of Section 9 of

the 1996 Act is not identical to Article 9 of the UNCITRAL Model Law but the

expression before or during arbitral proceedings used in Section 9 of the

1996 Act seems to have been inserted with a view to give it the same

meaning as these words have in Article 9 of the UNCITRAL Model Law. It is

clear, therefore, that a Party to an arbitration agreement can approach the

Court for interim relief not only during the arbitral proceedings but even

before the arbitral proceedings. To that extent Section 9 of the 1996 Act is

similar to Article 9 of the UNCITRAL Model Law.

It will also be useful to refer to a somewhat similar provision in the Arbitration

Act, 1996 of England. Section 44 of this Act gives the Court powers, which

are exercisable in support of the arbitral proceedings. Sub-section (3) of

Section 44 permits, in the case of urgency, the Court to make an order

contemplated by Sub-section (2) even on an application by a proposed party

to the arbitral proceedings. The expression used in this Sub-section party

or proposed party to the arbitral proceedings shows that where arbitral

proceedings have commenced then the application will obviously be of a

party to the said proceedings but where the arbitral proceedings have not

commenced a "proposed party' has been given the right to approach the

Court. A proposed party to the arbitral proceedings would, therefore, be one

who is party to an arbitration agreement and where disputes have arisen but

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 15 of 42

15

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

the arbitral proceedings have not commenced. While referring to Section 44

of the English Act in dealing with the question of grant of interim injunctions

in support of arbitral proceedings Russell On Arbitration 8, has stated as

under:

The Court may exercise its power to grant an interim injunction before there has

been any request for arbitration or the appointment of arbitrators, provided that

the applicant intends to refer the dispute to arbitration in due course.

The power to grant an interim injunction under Section 44 of the Act extends

to the granting of a Mareva injunction in appropriate cases. It may also

include granting an interim mandatory injunction, although the Court will be

slow to grant an injunction which provides a remedy of essentially the same

kind as is ultimately being sought from the Arbitral Tribunal.

The Supreme Court opined that this view correctly represents the position in

law, namely, that even before the commencement of arbitral proceedings the Court

can grant interim relief. The said provision contains the same principle, which

underlies Section 9 of the 1996 Act.9

Thus, under the 1940 act there was a difference of opinion as to whether

relief could be granted under the section before reference had been made to

arbitration. One view was that relief would not be given unless arbitration

proceedings were pending before the arbitrator.10 The other view was that relief

under the section could be granted before and in anticipation of any reference, and

before an order of reference was made, 11 there reason why the word pending

should be added before the words arbitration proceedings" in section 41(b), 1940

Act.12 Now S. 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 makes it very clear that

reliefs under the section can be granted either before or during arbitral

proceedings.

8 [21st Edition] at page 380

9

The Court also considered the decision in Channel Tunnel Group and France Manche SA v.

Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd., (1992) WLR 741 (CA), on appeal, 1993(2) WLR 262 (H12)

wherein construing section 12 (6) of the UK Arbitration Act 1950, STRAUGHTON, LJ observed as

under:

In my view this power can be exercised before there has been any request for arbitration or the

appointment of Arbitrators, provided that the applicant intends to take the dispute to arbitration in due

course. Whatever the meaning of reference to Section 12(6)(h) (and it is not always easy to

determine the precise meaning of the word in arbitration statutes). I would hold that the power of the

Court in such a case would be exercised for the purpose of and in relation to a reference.

10 Ranjit Chandra Mitter v. Union of India, AIR 1963 Cal 594.

11 Gokuldas v. Union of India, Al R 198:3 Ker 169.

12 Chandu Lot v. Brit-over Ltd., 52 CWN 451.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 16 of 42

16

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 17 of 42

17

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

PART B:POSITION UNDER ENGLISH LAW

The general principle is stated in Part 1 of the English Arbitration Act 1996 as

follows:

in matters governed by this Part [of the Act] the court should not intervene

except as provided by this part.

This statement of principle in the very first section of the Arbitration Act 1996

is clear recognition of the need to limit and define the court's role in arbitration. The

House of Lords has stated in this regard as under Whatever view is taken regarding the correct balance of the relationship

between international arbitration and national courts, it is impossible to doubt

that at least in some instances the intervention of the court may be not only

permissible but highly beneficial.13

The English courts could easily justify their role where the parties are English

and the arbitration is to follow the normal English rules of procedure. It is less easy

to justify in a case, conducted under the rules of an international arbitration body.

(for example the ICC), where the parties ,are foreign, and the only connection with

England being the parties' choice, directly or indirectly, to hold their arbitration there.

In Coppie-Levalin SA/NV v. Ken-Ren Chemicals and Fertilizers Ltd, 14 which

was decided prior to the enactment of the English Arbitration Act 1996, a distinction

was drawn between three groups of measures that involve the court in arbitration;

the first being purely procedural steps which an arbitral tribunal cannot order or

cannot enforce (eg. issuing subpoenas), the second being designed to maintain the

status quo the granting of interlocutory injunctions) and the third being designed to

ensure the award has its intended practical effect by providing a means of

enforcement if the award is not voluntarily complied with. It was pointed out that the

three groups entail differing degrees of encroachment on the tribunal's task of

deciding the merits of' the dispute and that the extent of such intrusion should

condition to an important extent the court's approach. Despite the changes made

by the Arbitration Act 1996, the distinction remains valid.

13 Per Lord Mustill in Coppee-Lavalin SA/NV v. Ken-Ren Chemicals and Fertilizers Ltd. (in

Liquidiation) (1994) 2 All E.R. 449 at 466 HL.

14 [1994] 2 All E.R. 449.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 18 of 42

18

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

The English Courts may intervene while arbitration proceedings are pending

and its powers to do so. They include power to extend time limits for commencing

the arbitral proceedings and for making the award, power to appoint arbitrators, to

decide disputes about the arbitrator's jurisdiction and to determine points of law. The

court also has power to remove an arbitrator and to appoint a replacement. The

court may also make other orders during the reference, and these are also

examined.

Under section 9 of the English Act, a stay must be granted unless the court is

satisfied that the arbitration agreement is null and void, inoperative, or incapable of

being performed. The court also has an inherent jurisdiction to grant a stay in

certain circumstances like stay proceedings brought in breach of an agreement to

decide disputes by arbitration.15 It is rarely necessary to invoke this power in view of

the statutory jurisdiction. The inherent jurisdiction may be appropriate though where

there is no arbitration agreement within the meaning of section 6 of the Arbitration

Act 1996 or where the arbitration clause is not immediately effective 16 or for some

other reason the Application falls short of the requirements for a stay under the

Arbitration Act 1996.

A stay based on the inherent jurisdiction may also be appropriate where there

are two defendants to the court proceedings, one of whom is not a party to the

arbitration agreement but claims through or under the other defendant by virtue of a

contract of agency.17 This touches on a particularly difficult issue in relation to

arbitration agreements. It most frequently arises in the context of groups of

companies, where for example one in the group has signed a contract containing an

arbitration clause or Group Company has performed the contract.

Under the English Law there is no requirement that the reference to

arbitration must have been started. Indeed, the fact that the dispute cannot

15 Channel Tunnel Group Ltd and Others v. Balfour Bveaty Construction Ltd and Others, [1993] 1

Lloyds Rep.291.

16 Id.

17

Roussel-Uclaf v. CD. Searle C5 Co. Ltd and G. D. Searle & Co. [1978] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 225 at 229

30. The court in that case was prepared to grant a stay based both on its inherent jurisdiction and on its

finding that one of the group companies was claimine through or under the other Rithin the mcaning

of s.1 of the Arbitration Act 1975. The words quoted do not appear in the Arbitration Act 1996 and the

decision has been criticised.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 19 of 42

19

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

immediately be referred to arbitration, because the matter is to be referred to

arbitration only after the exhaustion of other dispute resolution procedures will not

prevent the court from ordering a stay.18

18 Arbitration Act 1996, s.9(2) which followed the decision in Channel Tunnel Group Ltd and Olhers v.

Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd and Others [19931 1 Lloyds 1 Rep. 291, HL.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 20 of 42

20

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Chapter IIITHE NATURE OF RELIEF AS PROVIDED UNDER SECTION 9 OF THE

ACT

The present chapter discusses threadbare the various kinds of relief

contemplated under section 9 of the Act which the Courts are empowered to give to the

applicant. As discussed earlier, there existed a difference of opinion as to whether relief

could be given under this section before reference had been made to arbitration. Once

view was that relief could not be given unless arbitration proceedings were pending

before the arbitrator. The other view was that relief under the section could be granted

before and in anticipation of any reference, and before an order of reference was made,

there being no reason why the word pending should be added before the words

arbitration proceedings in section 41(b), 1940 Act. Now the present section 9 of the Act

makes it very clear that relief under the section can be granted either before or during

arbitral proceedings.

PART A:

ORDER FOR SALE OF GOODS [SECTION 9(ii)(a)]

Under this heading the Courts are empowered to order sale of goods, the

goods being defined under section 2 of the Sale of Goods Act, 1930 and moreover

so, in case where the goods are of a perishable nature.

PART B:

ORDER FOR PROTECTION OF FINANCIAL INTEREST [SECTION

9(ii)(b)]

In Global Co. v. National Fertilizers Ltd., the Delhi High Court held that a petitioner

cannot seek an interim order or the sole ground of protection of his financial

interests. The awardee has to prove the respondent's intention to effect, delay or

obstruct execution of the award. The court said19 It is true that the said Arbitration Act, 1940 stands repealed by the Act of

1996 and the provisions contained in the Code of Civil Procedure are not

applicable to the proceedings under the Act. Still, in the absence of

guidelines how the power for grant of relief under section 9(ii)(b) is to be

exercised by, the Court, the principles underlying the aforesaid sections are

to be applied. It is only on adequate material being supplied by the petitioner

that the Court can form opinion that unless the jurisdiction is exercised under

the said Section 9(ii) there is real danger of the respondent defeating,

delaying or obstructing the execution of the award made against it. On the

basis of the only ground of protection of financial interest of the petitioner, the

19 AIR 1998 Delhi 397 at 400.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 21 of 42

21

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

respondent, a Govt. of India Undertaking, cannot be legally directed to

furnish security for the amount of US$ 88,250 together with interest @ 9%

p.a.

It must be noted that the court has no power to direct an arbitrator to pass an

interim award and that too for a specified amount. 20 However, the court is competent

to pass an order of attachment before judgment by invoking the provisions of S. 9 of

the 1996 Act.

In case of security for costs, the courts will usually require a claimant, if it is a

foreign company out of India or a person out of India who does not possess

sufficient immovable property in India, to furnish security for all the costs incurred or

likely to be incurred by the respondent.21

The arbitral tribunal may ask for deposit by way of security for costs. The

deposit in advance may be supplemented afterwards according to exigencies. A

separate cost may be fixed linking it with the claim and counter claim. The deposit

has to be paid by the parties in equal share, though one party may pay the share of

the other in case of default. Where deposit is not made by a party in respect of a

particular claim or counter-claim, the tribunal may suspend or terminate the arbitral

process in respect thereof. At the end of the proceedings, the tribunal has to give an

account of the money in deposit and return the unused amount to the parties.

On of the effects of the provision is that the power of the court to order

security for costs becomes vested in the arbitral tribunal to the exclusion of the

court. This reform has been effectuated by the English Arbitration Act, 1996 also.

There also earlier the power was vested in the court. 22 The English Arbitration Act,

1996 does not specify the basis on which the security for costs should or should not

be granted. The tribunal has a broad discretion.

20 Union of India v. Om Construction and Supply Co., AIR 1994 All 334.

Such an order, if passed, mill

not be an interlocutory order, it would amount to case decided.

21 See, Order 25, Rule 1 of the Code of Civil Procedure.

22 For example, see Coppee-Lavalin SA v. Ken-Ren Chemicals & Fertilizers Ltd

(1994) 2 All ER 449.

Where a party was directed to give a security for the other parties costs though the only connection

with the English law was that the seat of arbitration was in England.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 22 of 42

22

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

There is no express or implicit provision in section 9 for payment of an interim

amount on account of damages, debt etc. If the parties have so agreed, the arbitral

tribunal will have the power to order a provisional payment under section 17.

PART C:INJUNCTION RESTRAINING ALIENATION OF PROPERTY [Sec. 9 (ii)

(c)]

While an arbitration proceedings was pending before the court, a temporary

injunction was granted preventing the defendant from alienating property.

An

application for the same was filled under S. 41(1)(b) read with Sch II, 1940 Act.

Section 41, 1940 Act stated that the court had the same power of making orders in

respect of any of the matters set out in Sch II as it would have in all civil

proceedings. One of the matters set out in Sch II was interim injunction. Thus it

was abundantly clear that the court had the power under S. 41(1)(b) read with Sch

II, 1940 Act to issue interim Injunctions with only this restriction that such injunctions

could be issued for the purpose and in relation to arbitration proceedings.

The

injunction was held to be rightly granted. 23 No injunction was allowed to prevent sale

of stock at the instance of a party who had failed to take off the stock and pay for it

in time.24

The word property is not defined in the Act. But in other relevant statutory

provisions, it is defined broadly to include any land, chattel or other corporeal

property of any description. The concept of property would appear to be wider than

goods.. An order under this section was refused where the applicant sought

inspection of an industrial process. The court said that such process could not be

regarded as a property.25

INJUNCTION TO PREVENT SALE OF SEIZED PROPERTY

23 R. K. Associates v. V Channappa, AIR 1993 Kant 247.

24 MVR Industries Ltd. v. Tribal Coop Mkg Development Federation of India Ltd., (1996) 1 Arb LR 393

(Delhi).

25 Tudor Accumulator Co. v. China Mutual, etc. Co., (1930) WN 201.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 23 of 42

23

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Where a contract for sale of timber was cancelled and trees already felled were

seized by the collector, an injunction was issued to prevent sale of such timber and

to preserve status quo.26 The court referred to Mustill and Boyd, Commercial

Arbitration27 and the decision in Food Corporation of India v. P. A. Ahammed

lbrahim28 to find support for the proposition that the censor of the jurisdiction of the

court on reference of the dispute to arbitration is only provisional and until a valid

award is passed the court retains its underlying jurisdiction which in certain

circumstances it will be entitled to assume. The court also had inherent power in the

matter,29 which can be exercised in the absence of any express or implied

prohibition in the underlying enactment.30 Hence the courts which are seized of

applications under the Arbitration Act can in the exercise of inherent jurisdiction pass

appropriate orders consistent with the procedural rules of CPC as may be necessary

for the ends of justice.

The court cited the following passage from Russell on Arbitrartion

Quite apart from these express powers (ie. Statutory powers similar to those

under the Arbitration Act) the court has always been willing to assist in this

way in proper cases.

The court, in order to preserve the status quo, in a case where one of the

parties to a contract had given a notice, purporting to dismiss the contractor,

restrained the party from acting on the notice until judgment or further order, or until

a references to arbitration provided for by the contract had been made.31

PART D:ORDERS FOR PRESERVATION OF EVIDENCE [Sec. 9 (ii) (c)] or

ANTON PILLER ORDERS

26 Brahamagiri B. Estate v. Thoman Joseph Kalathur, (1990) 2 Arb LR (Ker).

27 P. 123 (1982).

28 (1989) 1 Ker LT 251.

29 Newabgani Sugar Mills Co. lid. v. Union of India, AIR 1976 SC 1152.

30 I.M. D. Syndicate v. L T Commr. New Delhi, AIR 1977 SC 1348.

31 Foster v. Hastings Corporation, (1903) 87 LT 736.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 24 of 42

24

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Section 9(ii)(c) permits the court to make orders for preservation of evidence.

Such orders are frequently made for protection of intellectual property rights. Such

an order is commonly known as Anton Piller order.32 This order is a type of search

and seize order. It became necessary in the context of intellectual property rights

because the offending material was often destroyed by the infringing parties in order

to defeat the plaintiffs claim.

PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS

In a dispute between partners regarding partnership business, there were

claims and counter-claims between them about the custody of the documents. A

partner applied to the court under S. 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

for an order for production of documents. The court refused to pass any such order

because such an application is not maintainable under S. 9.33

PRODUCTION OF DOCUMENTS FROM THIRD PARTY

Section 12(4) of the English Arbitration Act, 1950 [replaced by the Arbitration

Act, 1996] empowered courts to issue summons for production of documents. It has

been observed that when this power is being exercised for production of documents

from the custody of a third party, the court should be vigilant to ensure that the

power is exercised for a legitimate purpose. Where the cargo was found to be

contaminated on discharge and the question as to the fitness of the ship for the

cargo arose, the aggrieved party obtained an order for discovery of documents

relating to the condition of the vessel from the association of ship owners. The order

of production was set aside. The order of production was found to be too wide and

not confined to legitimate purposes.

As to third parties, although the concluding words of section 44(2)(c) of the

1996 Act [UK] limit the court's power to authorize entry of premises to those

instances where the premises are in the possession or control of a party to the

32 Anton Piller K.G. v. Manufacturing Processes Ltd., (1976) Ch 55.

33 Narain Sahai Agrawal v. Santosh Rani, AIR 1998 Delhi 144.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 25 of 42

25

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

arbitration, there would seem to be no reason to read the preceding elements of that

sub-section as necessarily requiring that the properly of which detention or

inspection, etc., is sought must be in the possession or control of a party. The DAC

Report refers to the possibility of orders under section 44 of the Act having an effect

on third parties, and so supports an extended construction of section 44(2)(c). As

far as it may be relevant, it appears to have been assumed that the parallel

provisions of the 1950 Act permitted orders to be made directed at third parties. But

the position is not entirely clear, since in legal proceedings the power to make orders

for the detention and inspection, etc., of property in the hands of third parties is

exercisable only if the claim relates to personal injury or death; [see section 34(3) of

the Supreme Court Act 1981 and RSC Order 29, r.7(A)(2)]. The power in relation to

arbitration proceedings may be similarly confined.

PART E:INTERIM INJUNCTIONS [SECTION 9 (ii)(d)]

This section merely enables the court to grant interim relief by way of

injunction in a fit case.

There is nothing in the said section to warrant the

assumption that the well established principles governing the grant of temporary

injunctions, like prima facie case, balance of convenience and irreparable injury are

not applicable to the exercise of the power of under this section. In Binny Ltd. v.

Nizam sugars Ltd34 on the facts and circumstances of this case, the High Court

refused to grant an injunction in respect of bank guarantees.

The court in this

regard, relied upon the well established principles as reiterated by the Supreme

Court in Hindustan Steel Works Construction Lid. v. Tarapore & Co.35 An injunction

restraining encashment of bank guarantees can be granted by the court only in case

of fraud or in case where irretrievable injustice would be done if the bank guarantee

is allowed to be en-cashed. The apex court further held that the existence of a

serious dispute on the question who had committed breach of the contract or that

the contractor had a counterclaim against the beneficiary or that the disputes

between the parties had been referred to the arbitrators, etc., are not valid grounds

for granting an injunction restraining the enforcement of bank guarantees. It was

also held that the contract of bank guarantee between the bank and the beneficiary

34 (1997) 88 Comp Case 741 at 746 (AP).

35 (1996) 87 Comp Case 344.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 26 of 42

26

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

is independent of the primary contract between the party furnishing the bank

guarantee and the beneficiary and, therefore, encashment of an unconditional bank

guarantee does not depend upon adjudication of the dispute between the parties to

the primary contract.36

Where claims and counter-claims of the appellant and the respondent for

damages arising out of a contract were referred to arbitration, the court could during

the pendency of the arbitration proceedings grant an injunction restraining the

appellant from effecting recovery of the amounts claimed in the arbitration

proceedings from pending bills for amounts due from the appellants to the

respondent under other contracts. Such an order is negative not only in form but in

substance. It has no positive content. 37 Following this ruling, the M P High Court

held that even if an authority has terminated the contract wrongfully, it can not be

prevented from inviting fresh tenders for the same project.

Its liability to

compensation for breach of contract is the appropriate remedy to be perused by the

aggrieved contractor.38 The Supreme Court refused to issue an injunction to restrain

the Government from withholding payments due to the contractor under other

contracts. The court said that the injunctive power under the section is confined to

matters, which are for the purpose of and in relation to arbitration proceedings. In

this case, the matter complained of was not concerned with the contract under

dispute.39 The court could not direct the appellant to pay the amounts due to the

respondent under the other contracts, for such an order would not be for the

purpose of and in relation to the arbitration proceedings. 40 The court may direct the

detention of moneys lying in court 41 and other moneys42 pending the arbitration

proceedings.

36 See also National Thermal Power Corpn Ltd. v. Flowmore P Ltd., AIR 1996 SC 445, effect upon the

right of encashment where invocation has certain conditions to fulfill.

37 Union of India v. Raman Iron Foundry, (1974) Supp SCC 556 at pp. 561, 562.

38Taj Builders v. Indore Development Authority, AIR 1985 MP 146.

39 C Raghava Reddy v. Superintending Engineer, AIR 1988 AP 53.

The court considered Union of

India V. Raman Iron Foundry, AIR 1974 SC 1265, [order for maintenance of status quo] and H.M.K.

Ansari & Co. v. Union Of India, AIR 1984 SC 29: 1983 All LJ 1004.

40 Rawla Constructions v. Union of India, AIR 1977 Delhi 205.

41 Sundarlal Haveliwala v. Bhagwati Devi, AIR 1967 All, 400.

42 Sha Vaktavarmal Sheshmull v. Nainmull Umaji & Co., AIR 1962 Mad 436.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 27 of 42

27

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

The relief by way of injunction cannot be claimed as of right. A builder of

roads claimed that the Government should be prevented from allotting other works

on the roads built by him to other contractors because that would confuse

measurement of the work done by him. The court granted him the relief of ordering

the measurement of the work done by him but did not grant any further injunction.

The court said that good roads are a matter of public convenience and to hold up

the work on roads till the arbitrator's decision would be against canons of justice. 43

43 Mohinder Singh & Co. v. Executive Engineer, AIR 1971, J&K 130.

See also Alpine Industries v.

Union of India, (1988) 1 Arb LR 363 Delhi, the court did not interfere in the matter of reduction of rates

in the future while the claim was pending before the arbitrator, the court found that the contractor had

himself quoted reduced rates in other contracts.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 28 of 42

28

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

INJUNCTION TO PREVENT REVOCATION OF CONTRACT

Where during the pendency of the arbitration proceedings one of the parties

revoked the contract itself and other obtained an injunction against it revision

against the injunction was not allowed.44

INJUNCTION TO PREVENT BREACH OF CONTRACT

Injunction to prevent breach of contract or to order specific performance of

the contract are generally not allowed.45 Where the agreement provided for renewal

on mutually agreed terms, the termination or non-extension of the licence after the

expiry of the agreement was not a matter for arbitration. The only remedy was to

seek an order of specific performance for renewal. 46

PART F:APPOINTMENT OF RECEIVER [Sec. 9 (ii) (d)]

A receiver can be appointed in all cases in which it would appear to the court

to be just and convenient to do so.

A receiver may be appointed prior to the

commencement of legal proceedings and also prior to the commencement of arbitral

proceedings

Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation, Act, 1996, only deals with the

interim measure by die court. Obviously, it is not within the scope of the section to

inquire into the claim and the counterclaim made by both the parties in regard to the

custody of the articles beyond what has been admitted by the respondent. Although

the petitioner had failed to make out a case for appointment of a receiver of the

articles in possession of the respondent, still they need be protected being

44 Dashmesh Academy Trust v. V.K. Consttruction Works P. Ltd. (1988) 1 Arb LR 172 P&H.

The court

showed its agreeemnt with the rulling of the Allahabad High Court in Sunderlal Haveliwala v. Bhawati

Devi, AIR 1987 All 400 to the effect that a proceeding under S.20, 1940 Act (deleted from the 1996 Act)

was a part of arbitration proceedings.

45 Vinit Manchandra v. Rishi Co-op Group Housing Society (1987) 2 Arb LR 10 Delhi, the allotment of

contract was concelled on the allegation that it was a collusive affair

46 Indian Tourism Development Corpn. Ltd. v. Airport Authority of India (1997) 2 Arb LR 609, 620

(Delhi).

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 29 of 42

29

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

partnership property.

The respondent was, therefore, restrained from selling,

transferring or in any other way disposing them off pending dispute between the

parties in regard to them.47

Under Section 41(b), 1940 Act [as now in Sec. 9(ii)(d) of 1996 Act], the court

had power to pass an interim order of injunction or appointment of receiver. Where

a suit was pending before the court the court had power to appoint a receiver or

issue an interim injunction apart from the section.48 The power of appointing receiver

could be exercised even in a case where references to arbitration had been made

without the intervention of the court and no proceedings were pending in any court.

The court said that it would not seem proper that the court after being satisfied on

Prima facie evidence should be powerless in the matter of preservation or safety of

the property in dispute. The court could simultaneously appoint a receiver and stay

the suit under Section 34, 1940 Act [S. 8 of the 1996 Act].49

The fact that the arbitrator had no power to grant an injunction was a matter

which the court could take into account in exercising its discretion to stay the suit

under Section 34, 1940 Act.50 A car parking lot contractor whose term had expired

wanted to remain in possession for recouping losses caused by the conduct of the

owner.

He applied for references to arbitration and interim injunction for

maintenance of status quo. The court said that such injunction could not be allowed

to him. The effect of such an injunction would be that the owner would be prevented

from handing over the lot to the successful bidder, the contractor would enjoy quiet

possession without having to pay anything, though his period had expired.51

PART G:ANY OTHER MEASURE: JUST AND CONVENIENT [S. 9 (ii) (e)]

47 Narain Sahai Agarwal v. Santosh Rani, (I 997) 2 Arb LR 322 (Delhi).

48 Sharma Ice Factory v. jewel Ice Factory, AIR 1975 JK 25. It was held in, Goodudll India Ltd v. Tonu

Construction (1996) 2 Arb LR 602 (Delhi) appointment of receiver in a matter of hire-purchase

agreement for seizure of property was refused where the parties had revised the terms of the original

agreement and the right of seizure did not exist

49 Pini v. Ranocoroni, (1892) 1 Ch 633.

50 Willesford v. Watson, (1873) LR 8 Ch App 473.

51 Union of India v. Kishan Chand, (1990) 2 Arb LR 264 Delhi.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 30 of 42

30

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

The words 'just and convenient" employed in sub-clause (ii)(e) of section 9

of the Act, have been taken from sub-section (8) of Section 25 of the judicature Act

1873. The words in that Act are Just or convenient but they have been construed

to mean just and convenient The words 'just and convenient' do not mean that the

Court is to pass orders in respect of interim measures simply because the court

thinks it convenient they mean that the court should pass the orders for the

protection of rights or for the prevention of the injury according to legal principles.

The order is discretionary and the discretion must be exercised in accordance with

the principles on which the judicial discretion is exercised. These words were not

the part of section 41 of the Arbitration Act, 1940. Therefore, a wider discretion has

been given to the court under section 9 of the Act to pass interim orders. 52

There was a dispute between the parties to a joint venture about the

appointment of the managing director of their company. The appointment was going

to be confirmed at the next meeting of the shareholders. One party to the joint

venture contended that this meeting should be stayed because once the

appointment was confirmed it would become unimpeachable. The party had already

referred the matter for decision by arbitration in a foreign country. The court did not

consider it necessary to stay the meeting because even if the appointment was

confirmed, it would be subject to the decision of the arbitrator in the foreign

country.53 Where a company was developing the facility of cellular mobile telephone

service in a particular area, the court did not restrain, at the instance of the

company, the Union of India from interfering with the project on the ground that the

area belonged to the Punjab Telecom Circle. The mere fact of huge investment did

not turn the balance of convenience in favour of the company. The court could not

decide in such an application as to which telecom centre the area in question

belonged.54

DIRECTION FOR PAYMENT

52 State of Rajasthan v. Bharat Construction Co-, 1998 3 RAJ 7 at p. 11. The court refused in this case

to interfere in two orders, namely, that the State shall withhold the security deposit but shall not

withhold payment of running bills.

53 Suzuki Motor Corp. v. Union of India (1997) 2 Arb LR 477 (Delhi).

54 Escotel Mobile Communications Ltd. v. Union of India, (IM) 3 RAJ 307 Delhi: (1998) 2 Arb LR 384.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 31 of 42

31

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

An injunction against the Union of India directing it not to withhold an amount

due to the contractor under some other pending bills amounts to a direction to make

payment to the contractor. Such an order was beyond the purview of Section 41(b)

of the Arbitration Act, 1940.55 USHA MEHRA J said:To arrive at this conclusion support can be had from the observations of the

Supreme Court in the case of H.M. Kamatuddin Ansari & Co. v. Union of

India.56 While dealing with the power of the court to grant interim relief under

Section 41 la) and (b) of the (1940) Act, the Apex Court observed that an

injunction order restraining the Union of India from withholding the amount

due to the contractor under other pending bills virtually amounts to a direction

to pay the amount to the contractor/appellant. Such an order is beyond the

purview of clause (b) of Section 41 of the (1940) Act.

INJUNCTION AND STAY OF SUIT

Where an interim temporary injunction was considered necessary and was

granted, it was held that while staying the suit, the ad interim temporary injunction

should not have been stayed. A court can deal with an application for a temporary

injunction though it stays the suit.57

Appeals

A Letters Patent Appeal did not lie against an injunction granted under S.

41(b) and Sch II of the Arbitration Act, 1940. Chances of appeal had to be probed

under S. 39 of the 1940 Act. But there was no such provision under that section. 58

The court noted a decision of its own Bench 59 which rejected the argument that

orders passed by a single judge are orders under CPC and that would make the

55 Mahanagar Telephone Nigam Ltd. v. Vichitra Construction Pvt. Ltd., (1995) 2 Arb LR 479 (Delhi).

56 AIR 1984 SC 29. Followed in Sant Ram & Co. v. State of Rajasthan, AIR 1997 SC 2557 (1997) 1

Arb LR 209. The applicant here was seeking to restrain the Government from adjusting amounts due

to him under other contracts, relief not allowed.

57 Vashdev Bheroomal Pamnani v. M. Bipin Kumar, AIR 1987 Bom 226.

58 N.C. Bhall v. R.C. Bhalla (1990) 2 Arb.L.J. Delhi.

59

Subhash Chander Kakkar v. D. S. I. D. C., (1990) 2 DLT 21.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 32 of 42

32

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

appeal maintainable. Bench observed that when the court passes an order under

39 of CPC during the pendency of any proceedings commenced under any of the

provisions of the arbitration Act, 1940, the court was in effect exercising jurisdiction

under S. 41 of t e Arbitration Act 1940 read with the Second Schedule, of that Act.

Section 39 of the Arbitration Act 1940 clearly specified what were appealable orders.

An order passed under S. 41 of the Arbitration Act, 1940 read with the Second

Schedule and Order 29, Rules I and 2, CPC was not an appeal able order. 60

Revision was also not maintainable because interim orders did not finally adjudicate

or dispose of any claim or dispute between the parties.

The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 expressly provides in S.37 that

interim orders under S. 9 shall be appeal able.

60 The Bench relied on Banwari Ial Radhey.Mohan v. Punjab State Co-op Supply and Mktg Fedn. Ltd.,

AIR 1983 Delhi 402.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 33 of 42

33

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

Chapter IV: Interim Orders in Foreign Arbitration

PART A: THE SCHEME UNDER THE INDIAN ACT

It is an interesting proposition to examine whether the Indian Courts have the

power under the Arbitration Conciliation Act, 1996 to order interim measures in a case

where the place of arbitration is outside India. The answer is of great importance to

Indian businessmen, who in the wake of liberalization have entered into Joint Ventures

with foreign Companies. More often than not, these agreements provide for arbitration

at a venue outside India.

When disputes arise, the Indian businessman thinks of

approaching Indian Courts for interim relief. Do our Courts have this power under the

new Act of 1996?

This apparently simple question on has given rise to conflicting judgments of

various High Courts.61

This article proposes to examine such decisions in the

background of the UNCITRAL Model Law and the Law in various other countries. First,

though, it would be necessary to refer to the relevant provisions in the Arbitration &

Conciliation Act, 1996.

Under the English Law an application for a stay of legal proceedings is made

under section 9 of the English Arbitration Act 1996, whose provisions are

mandatory.62 Section 9 will apply even if the seat of the arbitration is abroad or no

seat has been designated or determined.63

At this juncture, attention should be adverted to Section 2, contained in Part I of the Act

and particularly to sub-section 1(f) that defines international commercial arbitration as

an arbitration relating to disputes arising out of legal relationships, whether contractual,

or not, considered as under the law in force in India when at least one of the parties is

61 Though the issue has now been settled by the Supreme Court, yet the propositions are indeed worth

examining.

62 See section 4 if the Arbitration Act 1996 and Sch. 1 to the Act for the mandatory provisions.

63

Arbitration Act 1996, s.2(2)

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 34 of 42

34

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

an individual who is a national of, or habitually resident, any country other than

India; or

a body corporate which is incorporated in any country other than India; or

a company or an association or a body of individuals whose central management

and control is exercised in any country other than India; or

the Government of a foreign country.

Section 2(5) defines the scope of Part I of the Act. In view of the particular relevance of

Sections 2(2) and 2(5), they are set out below: -

"2 (12) This Part shall apply where the place of arbitration is in India.

2 (5) Subject to the provisions of sub-section (4), and save in so far as is

otherwise provided by any law for the time being in force or in any agreement in

force between India and any other country or countries, this Part shall apply to all

arbitrations and to all proceedings relating thereto."

Section 2(7), which is also relevant, reads as follows

"2(7) An arbitral award made under this part shall be considered as a

domestic award."

It may be noticed that Section 9 titled 'Interim Measures etc. by Court' finds place

in Part I of the Act. No such provision is to be found in any other Part of the Act. The

question, which, therefore, arises, is whether or not Part I of the Act applies where the

place of arbitration is outside India.

The answer to such a question would, in the

ultimate analysis, depend on the true construction of the provisions extracted above.

However, before doing so, it is instructive to look at how the UNCITRAL Model Law, as

also other countries, have tackled the issue.

PART B:THE UNCITRAL MODEL LAW

The UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration has 36 Articles.

Article 1 is titled "Scope of Application". Article 1(2) reads as follows: Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 35 of 42

35

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

"The provisions of this Law, except articles 8, 9, 35 and 36, apply only if the

place of arbitration is in the territory of this State".

Article 9, which is referred to in Article 1.2, is also set out below:

"Arbitration agreement and interim measures by court - It is not incompatible with

an arbitration agreement for a party to request, before or during arbitral

proceedings, from a court an interim measures of protection and for a court to

grant such measures.

As a matter of history, it is interesting to note that Article 1.2 did not find place in the draft

Model Law.64 There was wide support for the so-called strict territorial criterion,

according to which the Law would apply where the place of arbitration was in that

State.65 Even while so deciding, the Commission was clear that the Court functions

envisaged in Articles 8, 9, 35 and 36 were to be entrusted to the Courts of the particular

State adopting the Model Law irrespective of where the place of arbitration was located

or under which law the arbitration was to be conducted. In view of this, Article 1(2) was

adopted in its final shape.

Thus, under the Model Law, i-n view of the specific exceptions to the principle of strict

territoriality, a Court would have the power under Article 9 to give interim directions,

irrespective of the place of arbitration.

64 The report of UNCITRAL on the adoption of the Model Law (paragraphs 72 to 81 of the Report) is set out

in The Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 - A Commentary by P. Chandrasekhara Rao at pages 349351

65 This also appears to be the genesis of Section 2(2) of the Indian Arbitration and Conciliation Act Act,

1996.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 36 of 42

36

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

PART C:THE POSITION IN ENGLISH LAW

In English Law, prior to the Arbitration Act, 19967 the House of Lords had held

that an arbitration held abroad and governed by some other curial law was completely

outside the legislation (Channel Tunnel Group Ltd. v. Balfour Beatty Construction Ltd. ,

1993 1 All ER 664 at 683). However, later, Section 2 was enacted, along the lines of

Article 1(12) of the Model Law and it reads as below

2. Scope of application of provisions

(1) The provision of this part applies where the seat of the arbitration is in

England and Wales or Northern Ireland.

(2) The following sections apply even if the seat of the arbitration is outside

England and Wales or Northern Ireland or no seat has been designated or

determined

(3) sections 9 to 11 (stay of legal proceedings, &c.), and

(4) section 66 (enforcement or arbitral awards).

The powers conferred by the following sections apply even if the seat of the

arbitration is outside England and Wales or Northern Ireland or no seat has been

designated or determined. But the court may refuse to exercise any such power if, in the

opinion of the court, the fact that the seat of the arbitration is outside England and Wales

or Northern Ireland, or that when designated or determined the seat is likely to be

outside England and Wales or Northern Ireland, makes it inappropriate to do so.

PART D:

JUDGMENTS OF VARIOUS COURTS IN INDIA

In a decision by Calcutta High Court in East Coast Shipping Ltd. v. M.J. Scrap Pvt.

Ltd.,66 the Applicants moved the Calcutta High Court for Interim protection and other

relief under section 8 and 9 of the 1996 Act.

The respondents took a preliminary

objection on the question of maintainability of the application in view of Section 2(2) of

the Act, mentioned above.The Applicants submitted that the Court had jurisdiction to

66 AIR 1997 Cal 168.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 37 of 42

37

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

hear the matter, placing particular emphasis on Section 2(5) of the Act. In reply, the

Respondents urged that if such an interpretation were to be accepted, it would render

section 2(2) otiose. Reference was made to the UNCITRAL Model Law to show that the

legislature had thought it fit to deviate there from and exclude Sections 8 and 9 from

operation of the Part I of the Act. The Learned Judge held that the interpretation as

urged by the Applicants would render section 2(2) otiose and it was well settled that the

Courts must always presume that the legislature in its wisdom intended that every part of

statute should be given effect. The Learned Single Judge also noticed that the global

scope of the relevant provision of the UNCITRAL Model Law was consciously omitted

from the 1996 Act. It was held that deviation from the Model Law revealed the intention

of the legislature to limit the scope of Part I of the Act to arbitration proceedings where

the place of arbitration was in India. It was, therefore, held that as the place of arbitration

was admittedly in London, the application was not maintainable in the Calcutta High

Court.

A similar conclusion was reached by a Division Bench of the Calcutta High Court

in titled Keventer Agro Ltd. v. Seagram Co. Ltd67. That matter concerned a dispute

between the parties arising out of a joint-venture agreement. The Court framed three

issues. Issue No.3 related to the power of the Court to pass interim orders. The Court

observed that power to pass in interim order in connection with a special Act must be

derived from that statute itself. It was held that there was no provision in Part II, chapter

I or any other portion of the 1996 Act applicable to foreign arbitration under the New York

convention which gave the Court such a power. Sections 9 and 17 of the Act were held

to be applicable to domestic arbitrations only, in view of Section 2(2). The Court justified

such exclusion on the policy ground that the main objectives of the 1996 Act were to

minimize the supervisory role of the Courts in arbitral proceedings.. The reliance by

Keventer on Article 8(5) of the International Chamber of Commerce Rules was held to

be- misplaced, since such rules had no statutory force and, in any case, jurisdiction

could not be conferred by consent. In the circumstances, the Court was of the view that

it did not have the power to pass any interim order in cases of foreign arbitration.

A notable decision of the Delhi High Court that was later overruled by the Supreme

Court, the latter decision being the current running view, is nevertheless discussed here.

67 AIR 1997 Cal 200.

Submitted by Vikas Kumar

Page 38 of 42

38

Seminar on Interim Measures under Section 9 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996

In Marriott International Inc. & Ors.v. Ansal Hotels Limited & Anr68, the Delhi High Court

upheld the contention of the respondents that as the arbitration proceedings were being

held before the Kuala Lumpur Regional Centre for Arbitration in Malaysia, section 9 of

the Act had no applicability and the petition of the apaplicant therefore was therefore, not

maintainable.