Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Pak India Relations Vis

Uploaded by

waqasdgi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views7 pagesv

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentv

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

40 views7 pagesPak India Relations Vis

Uploaded by

waqasdgiv

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 7

1

Pak India relations Vis-a-vis Afghanistan

The hostility between India and Pakistan lies at the heart of the current war in

Afghanistan. Most observers in the West view the Afghanistan conflict as a battle between

the U.S. and the NATO-led International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) on one hand, and

al-Qaida and the Taliban on the other. In reality this has long since ceased to be the case.

Instead our troops are now caught up in a complex war shaped by two pre-existing and

overlapping conflicts: one local and internal, the other regional.

Within Afghanistan, the war is viewed primarily as a Pashtun rebellion against President

Hamid Karzais regime, which has empowered three other ethnic groupsthe Tajiks, Uzbeks

and Hazaras of the northto a degree that the Pashtuns resent. For example, the Tajiks, who

constitute only 27% of the Afghan population, still make up 70% of the officers in the

Afghan army. Although Karzai himself is a Pashtun, many of his fellow tribesmen view his

presence as mere window-dressing for a U.S.-devised realignment of long-established power

relations in the country, dating back to 2001 when the U.S. toppled the overwhelmingly

Pashtun Taliban.

Beyond this indigenous conflict looms the much more dangerous hostility between the two

regional powersboth armed with nuclear weapons: India and Pakistan. Their rivalry is

particularly flammable as they vie for influence over Afghanistan. Compared to that

prolonged and deadly contest, the U.S. and ISAF are playing little more than a bit partand

they, unlike the Indians and Pakistanis, are heading for the exit.

Since the Partition of the Subcontinent in 1947, India and Pakistan have fought three wars

the most recent in 1971and they seemed on the verge of going nuclear against each other

during a crisis in 1999, when Pakistani troops crossed a ceasefire line and occupied 500

square miles of Indian Kashmir, including a Himalayan border post near the town of Kargil.

As tensions rose, the Pakistanis took ominous steps with their nuclear arsenal. President Bill

Clinton mediated a solution. In intense negotiations at Blair House in Washington over the

Fourth of July weekend, Clinton persuaded Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif to order a pullback

of his countrys forces to the Pakistani side of the line. That concession cost Nawaz his job

and, very nearly, his life. The army commander, Pervez Musharraf, mounted a coup and

sentenced Nawaz to death. Clinton intervened and Nawaz was exiled to Saudi Arabia.

2

It is easy to understand why Pakistan might feel insecure. Indias population (1.2 billion) and

its economy (GDP of $1.4 trillion) are about eight times the size of Pakistans (180 million

Pakistanis generating an annual GDP of only $210 billion). During the period of Indias

greatest growth, which lasted from 2006 to 2010, there were four years during which the

annual increase in the Indian economy was almost equal to the entire Pakistani economy.

In the eyes of the world, never has the contrast between the two countries appeared so stark

as it is now: one is widely perceived as the next great superpower, famous for its software

geniuses, its Bollywood babes, its fast-growing economy and super-rich magnates; the other

written off as a failed state, a world center of Islamic radicalism, the hiding place of Osama

bin Laden, and the only ally of the U.S. whose airspace Washington has been ready to violate

and whose villages it regularly bombs. However unfair this stereotyping may be, its not

surprising that many Pakistanis see their massive neighbor as threatening the very existence

of their state.

To defend themselves, Pakistani planners long ago developed a doctrine of strategic depth.

The idea had its origins in the debacle of 1971, when, in less than two weeks, India

crushingly defeated Pakistan in their third war. That conflict ended with East Pakistan, which

had risen up against West Pakistan, becoming the independent state of Bangladesh.

According to the Pakistanis narrative, the dismemberment of their countrywhich they

blame on Indiamade it all the more important to develop and maintain friendly relations

with Afghanistan, in large measure in order to have a secure refuge in the case of a future war

with India. The porous border offers a route by which Pakistani leaders, troops and other

assets, including its nuclear weapons, could retreat to the northwest in the case of an Indian

invasion.

For the idea to work, it is essential that the Afghan government be a close ally of Pakistan,

and willing to help fight India. When the Taliban were in power, they were seen as the

perfect partner for the Pakistani military. Although widely viewed in the West as medieval if

not barbaric, the Taliban regime was valued in Pakistan as fiercely anti-India and therefore

deserving Pakistani arms and assistance.

After the Taliban were ousted by the U.S. after 9/11, a major strategic shift occurred: the

government of Afghanistan became an ally of Indias, thus fulfilling the Pakistanis worst

fear. The president of post-Taliban Afghanistan, Hamid Karzai, hated Pakistan with a

passion, in part because he believed that the ISI had helped assassinate his father in 1999.

3

With Karzai in office, India seized the opportunity to increase its political and economic

influence in Afghanistan, re-opening its embassy in Kabul, opening four regional consulates,

and providing substantial reconstruction assistance totaling around $1.5 billion, with an

additional $500 million promised within the next few years.

Indias presence is still, even now, quite modest. According to Indian diplomatic sources,

there are actually fewer than 3,600 Indians in Afghanistan, almost all of them businessmen

and contract workers in the agriculture, telecommunications, manufacturing and mining

sectors. There are only 10 Indian diplomatic officers, compared to nearly 140 in the UK

embassy and 1,200 in the U.S. embassy. But the Pakistani military, which effectively controls

Pakistans foreign policy, remains paranoid about even this small an Indian presence in what

they regard as their strategic Afghan backyardmuch as the British used to be about

Russians in Afghanistan during the days of the Great Game.

For the Pakistani military, the existential threat posed by India has taken precedence over all

other geopolitical and economic goals. The fear of being squeezed in an Indian nutcracker is

so great that it has led the ISI to take steps that put Pakistans own internal security at risk, as

well as Pakistans relationship with its main strategic ally, the U.S. For much of the last

decade the ISI has sought to restore the Taliban to power so that it can oust Karzai and his

Indian friends.

To achieve this goal, the Pakistani military has relied on asymmetric warfare using jihadi

fighters for its own ends. This strategy goes back over 30 years. Since the early 1980s, the ISI

has consciously and consistently funded and incubated a variety of Islamic extremist groups.

Pakistani journalist Ahmed Rashid calculates that there are currently more than 40 such

extremist groups operating in Pakistan, most of whom have strong links with the ISI as well

as the local Islamic political parties.

Pakistani generals have long viewed the jihadis as a cost-effective and easily-deniable means

of controlling events in Afghanistansomething they briefly achieved with the Taliban

capture of Kabul in 1996. By the same means, the Pakistanis have kept much of the Indian

army bogged down in Kashmir ever since the separatist insurgency broke out in 1990. The

generals like using jihadis because they help foster a sense of nationalism based on the twin

prongs of hatred for India and the bonding power of Islamic identity.

4

It is unclear how many Pakistanis still endorse this strategy and how many are having second

thoughts. There are clearly those in the army who are now alarmed at the amount of sectarian

and political violence the jihadis have brought to Pakistan. But that view is contested by some

in both the army and the ISI who continue to believe that the jihadis are a more practical

defence against Indian hegemony than even nuclear weapons. For them, support for carefully

chosen jihadis in Afghanistan is a vital survival strategy well worth the risk.

It was in Kashmir in 1947 that Pakistan first used irregular tribal fighters to try to get its way,

sending Pashtun tribesmen over the border to march toward Srinagar, Kashmirs capital city.

Along the way they looted and killed and, among other atrocities, raped and murdered several

European nuns they found in a hospital and a convent. With covert British assistance in the

form of an airlift involving British transport planes, Indian troops eventually drove back the

Pashtun tribesmen. By the terms of a ceasefire signed on January 1, 1949, Kashmir was

effectively divided between India and Pakistan. The two countries would go on to fight

another war over Kashmir in 1965, and it has remained a cause of conflict ever since.

It was not just India that got off to a bad start with the new nation of Pakistan. Afghanistan

also had an uneasy relationship with the Land of the Pure (Pak means pure). Afghanistan

alone opposed Pakistani membership in the UN in 1947. As with India, borders and territory

were in dispute. Afghan leaders had never accepted the Durand line that the British drew in

1893 and, after Partition, Afghanistan was not about to recognize that line as its border with

Pakistan. The Afghan king, Zahir Shah, was especially keen to regain Peshawar, in a valley at

the eastern end of the Khyber Pass, which had once been the summer capital of the Afghan

empire. It had been in British hands since 1845, and was now to become part of Pakistan. To

this day most Afghans look on Peshawar as a lost Afghan city.

Mutual antipathy to Pakistan quickly brought India and Afghanistan together as natural allies

and in 1950 the two signed a friendship treaty. In the years that followed, India and

Afghanistan both attempted to destabilize Pakistan, giving aid and shelter to discontented

Pashtun and Baluchi nationalists. In 1961 Pakistan and Afghanistan went so far as to close

their borders and break off diplomatic relations with each other.

It was only the pressure of growing Soviet influence in Afghanistan in the 1970s that forced

the Afghan government to improve its relations with Pakistan. President Daoud Khan reached

out to Pakistan in 1977 as a counter-balance to the Soviets, and began talks with Prime

Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto with a view to settling their border disputes. In April 1978,

5

however, Daoud was overthrown in a Soviet-backed leftist coup, after which India was able

to regain its pre-eminent place in Kabul. Throughout the 1980s India expanded its influence

in Afghanistan, contributing to an ambitious series of development projectsbuilding

manufacturing plants and hydroelectric facilities, as well as supervising numerous irrigation

initiatives.

Pakistan meanwhile began to arm the mujahedin, the Islamic radicalssome, like Osama bin

Laden, from outside the countrywho fought the Soviet occupation. Their recruitment was

always controlled by the ISI, but was originally also funded by the Saudis and the CIA.

Pakistan also began sending the jihadis into Indian Kashmir during the 1980s. As Hamid

Gulthe ultra-hardline former director of the ISI during that periodonce explained to me:

If they [the ISI] encourage the Kashmiris, it's understandable. The Kashmiri people have

risen up in accordance with the UN charter, and it is the national purpose of Pakistan to help

liberate them. If the jihadis go out and contain India, tying down their army on their own soil,

for a legitimate cause, why should we not support them?" Next to him in his Islamabad living

room as he spoke lay a large piece of the Berlin Wall presented to him by the people of

Berlin for "delivering the first blow" to the Soviet Empire through his use of jihadis in the

80s.

In an attempt to limit Pakistans influence after the fall of the pro-Soviet Afghan regime in

1989, India began its support of the Northern Alliance under the command of Ahmad Shah

Massoud, a Tajik leader who also had assistance from Iran and Russia. India continued to

supply Massoud with high-altitude warfare equipment, defense advisors, and helicopter parts

and technicians after the rise of the Pakistan-sponsored Taliban.

The period of Taliban rule, from 1994-2001, was the high point of Pakistans influence in

Afghanistan. India, which did not recognize the regime, was forced to close its embassy and

all its consulates and, with ISI encouragement, Afghanistan quickly became the base for a

whole spectrum of anti-Indian groups, including Lashkar-e-Taiba, which, in 2008, would

execute the deadly assault on Mumbai.

As the Taliban, supported by regular Pakistan troops, pushed the Northern Alliance into ever

smaller corners of Afghanistan toward the end of the 90s, India as well as Iran continued to

send supplies to the increasingly beleaguered Massoud forces. In 2001 India built a hospital

6

at their airbase in Tajikistan so that there would be a place to which they could ferry wounded

Tajik soldiers for treatment.

India and Pakistans jostling in Kabul dates back to the Cold War and before. When war

broke out after the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan, India and Pakistan supported rival anti-

communist factions. India sided with rebels opposed to Islamic extremism; Pakistan backed

the group that eventually became the Taliban. Since the Bush administrations 2001 invasion,

however, the US has pressured India to limit its Afghanistan role, to prevent Pakistan from

withdrawing support for the war and cutting vital US supply lines.

With the US now ready to bring its soldiers home, India and Pakistan are again wrangling for

control. Both foresee disaster if the other were to gain the upper hand. Islamabad fears that

India would use Afghanistan to aid insurgents in Pakistans nearby Baluchistan province,

where rebellion has simmered since the 1970s. Pakistan also regards control over Kabul as

vital to its military doctrine of strategic depth under which Afghanistan would serve as a

refuge where its leaders could lead a counterattack in the event of an Indian invasion.

For its part, India fears that resurgent Islamic militancy in Afghanistan will stoke violence in

Indian-administered Kashmir, by providing a safe haven and training ground for militants

like Lashkar-e-Taiba, perpetrators of the 2008 Mumbai attacks. So far, India looks to be

losing the struggle. New Delhi has earmarked nearly $2 billion for infrastructure projects and

humanitarian initiatives in Afghanistan since the US invasion. The most recent survey on the

subject, a 2009 BBC/ABC News/ARD poll, found that 74 percent of Afghans hold favorable

opinions toward India and only 8 percent feel the same about Pakistan. Yet Pakistan's proxies

seem poised to take over.

Meanwhile, India is loath to bolster its economic engagement with boots on the ground. We

have to be very cautious because we don't want to begin to bear the burden of supporting the

new Afghan government against the combination of the Taliban and Pakistan by offering

security support, said former Indian Foreign Secretary Kanwal Sibal in an interview to

GlobalPost. Their needs will keep increasing.

Consistent with that thinking, earlier this month New Delhi formally rejected Afghan

President Hamid Karzai's request for weapons to help his regime fight the Taliban. Indian

Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid obliquely parroted a refrain commonly spoken by US

7

officials: It is a fragile area, there are stakeholders, there are other people. We don't want to

become part of the problem." Or part of the solution, others contend.

Meanwhile, Pakistan has a head start in the latent battle for Afghanistan. Already, Pakistans

Taliban allies control most of Afghanistan's southern countryside. President Karzai who is

perhaps more friendly toward New Delhi than he is toward Washington faces a likely

defeat in national elections next year.

The Obama administration has perhaps unwittingly helped Islamabad as well. By signalling

its openness to negotiate with the Taliban in June and leaking the possibility of a complete

withdrawal of US troops the so-called zero option. America has further bolstered

Pakistan's hopes of regaining control over the war-torn country.

You might also like

- The Success PrinciplesDocument60 pagesThe Success Principleswaqasdgi100% (5)

- 40 RabbanaDocument32 pages40 RabbanaAnisur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Unusual ProphesiesDocument103 pagesUnusual ProphesiesMike Gary Hires100% (5)

- The Political Crisis of Pakistan in 2007 by Adama Sow & Schoresch DavoodiDocument55 pagesThe Political Crisis of Pakistan in 2007 by Adama Sow & Schoresch DavoodiAamir MughalNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Role in The Region PDFDocument7 pagesPakistan's Role in The Region PDFsalmanyz6No ratings yet

- NAME MEANING LISTDocument79 pagesNAME MEANING LISTbpraveensinghNo ratings yet

- Pak-Afghan Relations ChallengesDocument6 pagesPak-Afghan Relations Challengesshoaib625100% (2)

- Operation KashmirDocument27 pagesOperation KashmirShahzad Masood Roomi100% (1)

- Al Khadir Jesus El Cristo Ibn Arabi UryabiDocument32 pagesAl Khadir Jesus El Cristo Ibn Arabi UryabiTomas Israel RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Paper IIDocument22 pagesKnowledge Paper IIparrot15894% (16)

- The Arabian and Turkish Tuning Systems: Dr. Roula BaakliniDocument4 pagesThe Arabian and Turkish Tuning Systems: Dr. Roula BaakliniRoberto BernardiniNo ratings yet

- Proxy War & Pak Relation With NeighborsDocument25 pagesProxy War & Pak Relation With NeighborsAsif Khan Shinwari100% (3)

- History of Bangladesh Liberation WarDocument21 pagesHistory of Bangladesh Liberation WarlindrhfNo ratings yet

- The War in Afghanistan Since 1979 and Its Impact On, and Challenges To Pakistan in Post 2014 EraDocument6 pagesThe War in Afghanistan Since 1979 and Its Impact On, and Challenges To Pakistan in Post 2014 EraTELECOM BRANCH100% (1)

- HEC Attestation FormDocument2 pagesHEC Attestation Formmalikimran81% (54)

- Pakistan's Geopolitical ImportanceDocument17 pagesPakistan's Geopolitical ImportanceZeeshan KhalidNo ratings yet

- Strategic Insight: Rough Neighbors: Afghanistan and PakistanDocument10 pagesStrategic Insight: Rough Neighbors: Afghanistan and PakistanUsama TariqNo ratings yet

- Afghanistan and Regional ActorsDocument31 pagesAfghanistan and Regional ActorsAwais KhanNo ratings yet

- PST Assin 2Document4 pagesPST Assin 2HASHAM KHANNo ratings yet

- Pakistan and The "War On Terror" - Middle East Policy CouncilDocument4 pagesPakistan and The "War On Terror" - Middle East Policy CouncilasadzamanchathaNo ratings yet

- PAKISTAN'S ROLE AGAINST TERRORDocument11 pagesPAKISTAN'S ROLE AGAINST TERRORHASHAM KHANNo ratings yet

- Heartland - 2008 01 The Pakistani BoomerangDocument110 pagesHeartland - 2008 01 The Pakistani Boomeranglimes, rivista italiana di geopoliticaNo ratings yet

- Bearden Testimony 091001 ADocument7 pagesBearden Testimony 091001 Awhvn_havenNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Relations With United StatesDocument18 pagesPakistan Relations With United Statesmarshians_0072011100% (1)

- Alignment With The West Pakistans MotivesDocument9 pagesAlignment With The West Pakistans MotivesSikandar HayatNo ratings yet

- India and Pakistan Compete for Influence in AfghanistanDocument3 pagesIndia and Pakistan Compete for Influence in AfghanistanSheel SumitNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Americas Problem PartnerDocument3 pagesPakistan Americas Problem PartnerWaleed AliNo ratings yet

- PakistanDocument9 pagesPakistanRahim ShahNo ratings yet

- Afghanistan and Regional ActorsDocument28 pagesAfghanistan and Regional ActorsMuhammad AteeqNo ratings yet

- Afghanistan's Complex Regional Relations and HistoryDocument41 pagesAfghanistan's Complex Regional Relations and Historysaad aliNo ratings yet

- Afghanistan Pak RelationsDocument2 pagesAfghanistan Pak RelationsSaira RasulNo ratings yet

- Pakistans Anxieties Are Incurable So Stop Trying To Cure ThemDocument4 pagesPakistans Anxieties Are Incurable So Stop Trying To Cure ThemjoshuatwhiteNo ratings yet

- Vivek Issues N Otions September October 2014Document89 pagesVivek Issues N Otions September October 2014Vivekananda International FoundationNo ratings yet

- 0339 Faizan AmirDocument24 pages0339 Faizan Amirsyed aliNo ratings yet

- Iran-Pakistan RelationsDocument15 pagesIran-Pakistan RelationsMalik Hanif100% (1)

- Five Dangerous Myths About PakistanDocument27 pagesFive Dangerous Myths About Pakistanjavediqbal87982550No ratings yet

- Pakistan Foreign PolicyDocument9 pagesPakistan Foreign PolicyIrfan Afghan95% (21)

- The Genesis of Taliban in AfghanistanDocument18 pagesThe Genesis of Taliban in AfghanistanParidhi SharmaNo ratings yet

- In Search of Identity and Security: Pakistan and The Middle East, 1947-77Document22 pagesIn Search of Identity and Security: Pakistan and The Middle East, 1947-77Haytham NasserNo ratings yet

- A History of Pak-US RelationsDocument4 pagesA History of Pak-US RelationsFaizan Ahmed SamooNo ratings yet

- US-Pakistan RelationsDocument20 pagesUS-Pakistan RelationsTahir WagganNo ratings yet

- The Best Way Forward On The New AfghanistanDocument8 pagesThe Best Way Forward On The New Afghanistanneat gyeNo ratings yet

- PakistanDocument112 pagesPakistangladiatorranaNo ratings yet

- Durand Line HusainDocument5 pagesDurand Line HusainHusain DurraniNo ratings yet

- IndiaPakistan KeylorDocument5 pagesIndiaPakistan KeylorNancy LiNo ratings yet

- Afghanistan-Pakistan Relations Involve Bilateral Relations BetweenDocument8 pagesAfghanistan-Pakistan Relations Involve Bilateral Relations BetweenHina MoqueemNo ratings yet

- 3rd Lecture Afghanistan QuagmireDocument43 pages3rd Lecture Afghanistan QuagmireKhalil AhmedNo ratings yet

- China Inherits Obama S Nightmare: by Ahmed RashidDocument3 pagesChina Inherits Obama S Nightmare: by Ahmed RashidaslamkatoharNo ratings yet

- Foreign Policy Challenges For PakistanDocument9 pagesForeign Policy Challenges For PakistanMuhammad HanifNo ratings yet

- 4th Era of Pakistan Foreign Policy (2001Document20 pages4th Era of Pakistan Foreign Policy (2001Ateeb R-azaNo ratings yet

- Pakistan Urged to Press Taliban on Power-Sharing, Violence ReductionDocument20 pagesPakistan Urged to Press Taliban on Power-Sharing, Violence ReductionJunaid IftikharNo ratings yet

- Pakistan-The Most Dangerous Place in The WorldDocument5 pagesPakistan-The Most Dangerous Place in The WorldwaqasrazasNo ratings yet

- Musharraf's TransgressionsDocument3 pagesMusharraf's TransgressionsHadiNo ratings yet

- Post-Partition Notes by SelfDocument5 pagesPost-Partition Notes by SelfAmna AslamNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Foreign PolicyDocument5 pagesPakistan's Foreign PolicyAmna SaeedNo ratings yet

- March 2020-Final PTM ArticleDocument10 pagesMarch 2020-Final PTM ArticlePakhtoon HalakNo ratings yet

- Thematic Analysis of Afghanistan and Pakistan's Shared HistoryDocument1 pageThematic Analysis of Afghanistan and Pakistan's Shared HistoryUmar IbrahimNo ratings yet

- 3rd Lecture AfghanistanDocument43 pages3rd Lecture Afghanistannu99664No ratings yet

- MA History 5688Document3 pagesMA History 5688zubash durraniNo ratings yet

- Teach A Course: Presentation SubtitleDocument23 pagesTeach A Course: Presentation SubtitleMr TaahaNo ratings yet

- Afghanistan ImbroglioDocument4 pagesAfghanistan Imbrogliosalmanyz6No ratings yet

- Pakistan A Hard Country - Long-1-99 PDFDocument23 pagesPakistan A Hard Country - Long-1-99 PDFabuzar4291No ratings yet

- Almost Lost WarDocument4 pagesAlmost Lost WarMishal AsifNo ratings yet

- Afghanistan: A Country Easier To Take Than To Hold'Document46 pagesAfghanistan: A Country Easier To Take Than To Hold'Tooba ZaidiNo ratings yet

- Pakistan's Geostrategic ImportanceDocument3 pagesPakistan's Geostrategic ImportanceSana YounasNo ratings yet

- Challenges To Pakistan Foriegn PolicyDocument7 pagesChallenges To Pakistan Foriegn PolicyShahzad MIrzaNo ratings yet

- Indo-Pak WarDocument4 pagesIndo-Pak WarlakhanNo ratings yet

- Pakistan at the Crossroads: Domestic Dynamics and External PressuresFrom EverandPakistan at the Crossroads: Domestic Dynamics and External PressuresRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Recommendation LetterDocument1 pageRecommendation LetterwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Character Certificate VerificationDocument1 pageCharacter Certificate VerificationwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Understanding CSS Syllabus for Pakistan AffairsDocument4 pagesUnderstanding CSS Syllabus for Pakistan AffairswaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Riba and Islamic BankingDocument33 pagesRiba and Islamic BankingIbnrafique100% (3)

- 171759Document30 pages171759waqasdgiNo ratings yet

- TextDocument103 pagesTextwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Draft of Self Regulatory Code of ConductDocument5 pagesDraft of Self Regulatory Code of ConductwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Blasphemy Law Fact SheetDocument5 pagesBlasphemy Law Fact SheetJawadattariNo ratings yet

- Pakisatn Beyond CrsisDocument3 pagesPakisatn Beyond CrsisCanna IqbalNo ratings yet

- Css Recommended BooksDocument1 pageCss Recommended Bookswaqasdgi100% (1)

- Pakistan Engineering Council: Application Form For Registered EngineerDocument7 pagesPakistan Engineering Council: Application Form For Registered EngineerSufian AhmadNo ratings yet

- Civil Military RelationsDocument17 pagesCivil Military RelationswaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Area 3 & 4Document52 pagesArea 3 & 4waqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Css Recommended BooksDocument1 pageCss Recommended Bookswaqasdgi100% (1)

- Democracy, Key Points For EssayDocument2 pagesDemocracy, Key Points For EssaywaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- 171759Document30 pages171759waqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Land ReformsDocument3 pagesLand ReformswaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Economic System in Islam PDFDocument6 pagesEconomic System in Islam PDFZeeshan AliNo ratings yet

- JKDocument2 pagesJKwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Schedule of Graduate Assessment TestDocument1 pageSchedule of Graduate Assessment TestwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- 29 - Final - ExamDocument5 pages29 - Final - ExamwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- M. FileDocument14 pagesM. FilewaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- SaifDocument2 pagesSaifwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

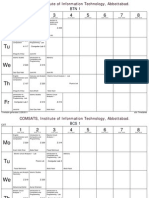

- Time TableDocument145 pagesTime TablewaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- New Text DocumentDocument2 pagesNew Text DocumentwaqasdgiNo ratings yet

- 32 - Project Time Management 1Document5 pages32 - Project Time Management 1waqasdgiNo ratings yet

- Medina CharterDocument9 pagesMedina Charterkirpa100% (1)

- The Cultural Heritage of PakistanDocument276 pagesThe Cultural Heritage of PakistanPanchaait PK100% (1)

- M 71 FDocument157 pagesM 71 FarsiukasNo ratings yet

- 6872 12055 1 PB PDFDocument14 pages6872 12055 1 PB PDFklepon ploloNo ratings yet

- Albert Memmi - Decolonization and The DecolonizedDocument7 pagesAlbert Memmi - Decolonization and The DecolonizeddekonstrukcijaNo ratings yet

- TG Iqtf 004082Document131 pagesTG Iqtf 004082Mbamali Chukwunenye0% (1)

- Chapter 1Document35 pagesChapter 1Ju RaizahNo ratings yet

- Sacrifice: Your Path To Becoming MuslimDocument2 pagesSacrifice: Your Path To Becoming MuslimJanuhu ZakaryNo ratings yet

- Pakistan in Search of IdentityDocument149 pagesPakistan in Search of IdentityFahadNo ratings yet

- Introduction of Darul Uloom Sabeelus Salam, HyderabadDocument5 pagesIntroduction of Darul Uloom Sabeelus Salam, HyderabadmusarhadNo ratings yet

- Bani NazirDocument5 pagesBani NazirtanvirNo ratings yet

- Newspaper Index: A Monthly Publication of Newspaper's ArticlesDocument33 pagesNewspaper Index: A Monthly Publication of Newspaper's ArticlessherNo ratings yet

- Why Is Bangladesh Booming? Kaushik BasuDocument3 pagesWhy Is Bangladesh Booming? Kaushik BasuAkash_C1992No ratings yet

- Frederick Appiah Afriyie JIAN Jisong VINCENT Arkorful Anatomy of Africa'S Evil Siamese Twins: A Comparative Research of Boko Haram and Al-ShababDocument23 pagesFrederick Appiah Afriyie JIAN Jisong VINCENT Arkorful Anatomy of Africa'S Evil Siamese Twins: A Comparative Research of Boko Haram and Al-ShababAMOEBNo ratings yet

- ELC Academic Calendar for 2020/2021 Academic YearDocument6 pagesELC Academic Calendar for 2020/2021 Academic YearChristien EkawatiNo ratings yet

- Yoga of Islamic PrayerDocument2 pagesYoga of Islamic PrayerMustafa A JariwalaNo ratings yet

- Theory Project ReportDocument18 pagesTheory Project ReportwasemNo ratings yet

- Modul RamadhanDocument2 pagesModul RamadhanFadilNo ratings yet

- The Caliphate FilesDocument7 pagesThe Caliphate FilesRENGANATHAN PNo ratings yet

- The Life and Times O Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi: ©ottor of (JiloisopfipDocument375 pagesThe Life and Times O Shaikh Ahmad Sirhindi: ©ottor of (JiloisopfipAli Asghar ShahNo ratings yet

- Hanafi DivorceDocument22 pagesHanafi DivorceSo' FineNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Education System: Certificates, Diplomas & DegreesDocument36 pagesBangladesh Education System: Certificates, Diplomas & DegreesSadia AkterNo ratings yet

- 5 Things To Do On The Night of Bara'a (Shabe-Baraat)Document6 pages5 Things To Do On The Night of Bara'a (Shabe-Baraat)IslamResources4allNo ratings yet