Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Robeano Forecasting

Uploaded by

barath1986Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Robeano Forecasting

Uploaded by

barath1986Copyright:

Available Formats

DEMAND FORECASTING: REALITY vs.

THEORY

or

WHAT WOULD I REALLY DO DIFFERENTLY , IF I COULD FORECAST DEMAND ?

NATIONAL MANAGEMENT SCIENCE ROUNDTABLE

NASHVILLE, TENNESSEE

MAY 13, 1991

Steven Robeano

Senior Logistics Engineer

Ross Laboratories

6480 Busch Boulevard

Columbus, Ohio 43229

(614) 624-6124

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 2 of 14

You know, I must be one of those people the airline has in mind when the pilot gets on

the PA system just before take-off and says,

"Good morning, you are on Delta Airlines flight 1424 to Nashville."

First: I've never gotten on a wrong plane.

Second: Don't they look at your ticket when you check-in?

It doesn't matter, I still worry about it until I hear the pilot's confirmation.

Before we get down to business here, I'll describe the flight we are on for people like

me.

SUMMARY

Formally or informally, the forecast drives the firm. Techniques range from seemingly

none at all, or at most "forecasting by desire", to complex and "sophisticated"

algorithms and models that require tremendous processing power. Usually, it's a

mixture of dozens of methods and options. "What works and what doesn't, rarely

depends directly on time, money, or other forms of business horsepower. It is an

organizational problem, subject to a visible formal structure and also to an often

hidden informal one.

This session will look at forecasting as a form of applied common sense. In a

commercial business setting, simple doesn't necessarily mean weak and advanced

mathematics doesn't necessarily mean accurate or timely.

Sales and Marketing functions in a firm often use several forecasting methods in an

effort to improve accuracy. The Logistics and Operations functions also often use

several methods, with each area complaining that the other's forecasts are not

compatible with their area's needs. There is a lot of resistance to reconciliation. Often

the cause is simply organizational inertia. Other times each area has good reason for

being so parochial. We are going to look at organizational ways to turn these conflicts

into constructive cooperation.

In the '70s and '80s many firms with large distribution systems, including Ross,

installed computerized statistical forecasting systems for logistics. I have talked with

many businesses before, during, and after their selection and installation processes.

Generally all of them showed an improved level of detail and improved accuracy. The

methods and the software may vary somewhat, but most were carefully studied,

tested, and evaluated before implementation.

Users have lots of rosy expectations when planning a new system. Ross Logistics, for

instance, wanted lower finished goods inventory and lower freight costs without

compromising customer service. Others firms may want to drive a production or

purchasing system. Ross got what it wanted, and so it seems, did most others.

But... (did you ever notice that the important stuff always comes after the "but" ? ) But

are whiz-bang forecasters like us getting everything we had hoped for? One benefit

many of us expected was a total integration of the forecast throughout the business,

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 3 of 14

or in other words, getting everyone in the choir to sing off the same script. This is a

constant struggle between departments in any large business and by the end of this

session you should have a better idea why. Hopefully, you also will be able to identify

and deal with similar problems in your own organization, problems which odds

strongly lead me to suspect your organization shares, visible or not. As time allows, we

would like some information from you on your experiences.

I'm not here to teach you forecasting. Any one of you could teach it as well as I could.

In planning this session I assumed you had a solid understanding of the forecast

methods you are using in your own shop. To be candid with you, I also expected that

you were probably at least moderately uncomfortable with both how and why the

various parts of your firm "do their own thing" with forecasts.

TAKE A WALK AROUND YOUR ORGANIZATION. WHAT ARE WE DOING?

Everybody has a PC.

Everybody has a spreadsheet program.

Everybody has inventory planning and tracking programs.

Everybody has a forecast program.

Everybody has their own forecast.

Whatever are we doing?

FORECAST SOUP

Marketing, sales, finance, purchasing, logistics, production scheduling, and so on, all

see reasons for using the forecasting method or methods they have chosen. Before we

try to manage this conflict, we need some grounding in each other's needs. You don't

have to be an expert carpenter to be able to converse with one. It sure helps to

recognize the tools when you see them, and to have a good idea of what they can and

cannot do. It's tough to build furniture with a saber saw. It can be done, but it's not

very practical.

We are also going to look at how different disciplines recognize the need to forecast

and then cope with that need. Evaluation, comparison, and communication are

required.

THE UNDERLYING QUESTIONS: What, Where, and When ?

Each person in a large firm who is involved with any kind of forecasting generally has

a good idea why the organization needs a demand forecast. Lets start at home first.

1. Do you really understand why you believe you need your own forecast?

2. If you were asked or ordered to abandon your area's internal forecast, what aspects

lost are of strategic importance to your role?

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 4 of 14

Here's a non-standard thought process to get at point #1.

Ross Laboratories manufactures and markets infant and adult nutritionals, and

personal care products. The personal care items have lots of new products in unstable

channels of distribution. The nutritionals, however, also with significant numbers of

new products, are distributed through stable channels. They are mostly high volume

and most are produced to a forecast.

If supply, demand, and transit times were totally predictable and free of random

variation, there would be no need for safety stock in the field. We would ship stuff to

arrive exactly when needed. UPS, RPS, and FED-EX would love it, and the railroads

and truckers would be looking at career opportunities elsewhere. Lucky for them we

can't afford to ship cans of infant formula one-at-a-time even if we did know exactly

when the customer would want them, or where and when the warehouse system

would need them to fill an order. So, we ship/replenish in quantity. The only inventory

really needed with a perfect forecast would then be a function of their replenishment

frequency and quantity. Service level could still be 100 percent as long as "what,

where, and when" were known exactly and there was no variance in transportation

performance.

Of course, not one word of the proceeding is realistic. I don't trust the gas gauge on my

car. I only have a rough idea of what I'll use getting to work and back. To provide high

service at low cost, the logistics function needs to know how much of what is going to

be needed both where and when, as exactly as it can. The game is simply one of "how

low can I go" without running out of gas or spending too much time at service stations

buying a gallon at a time.

THE OBLIGATORY "BRIEF" HISTORY

Ross is a manufacturer of nutritional health care products. Our first post World War II

logistics forecasting system (circa 1950) was manual, and was "THIS QUARTER'S

FORECAST IS LAST QUARTER'S ACTUAL." In those days, its true, inventory was

cheaper but it was really used to fill information gaps and delays, lots and lots of

them. Inventory records in the field were days and often weeks behind. We didn't know

we had sold something until 3 to 5 days after we sold it.

The major stated reason for not using Marketing's forecast was: "Too aggregated

temporally and geographically." No doubt! Marketing forecasted up to 10 stockcodes as

one group, in 8 regions, quarterly. The major unstated reason for the distribution

forecast was to give planners a stationary target to shoot at. The result was simple.

Anybody that needed a working forecast did one on their own. No one outside of

Distribution used Distribution's forecast.

In the mid '60s we got our first computer. (I carry a bigger one in my briefcase.) The

Accountants bought it to account, but the Distribution people talked the Accountants

into letting them "forecast" once every three months or so. Each quarter a forecast was

generated where the value for all of the next 3 months was the average of the last 3

months. In. talking to the old-timers, I found that no one outside Distribution used

that forecast either. One thing is certain, that forecast sure introduced a lot of

smoothing. The planners just loved it.

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 5 of 14

In the late '60s we installed our first real system. It was a 3-month weighted moving

average... still naive yes, but at least it was monthly. We wanted to use exponential

smoothing a la R. G. Brown and seasonal-decomposition a la Julius Shiskin. Sorry, no

soap, not on a computer already running 3 shifts that had less memory than a vanilla

XT.

Weighted moving averages are great for smoothing but they badly under-shoot a rising

series and over-shoot falling ones. They not only butcher trends, but they ignore cycles

and seasonals. Was it Freud who said, "Smoothing is not necessarily forecasting.

Sometimes it is just smoothing"?

The replenishment planners noticed this, unfortunately, and asked for an override

option,... an option which they almost invariably used. They used optical forecasting

techniques or the eyeball method. They spoke to the field warehouses several times a

day, pumped sales force people who called in, chatted with customers, and generally

ignored the computer. On short-term forecasting accuracy, I had a rough time beating

them head-to-head. The only real advantage I had was that I killed them on volume.

They could only handle a few items while the computer handled them all. They weren't

concerned about all that however. Crushed again.

Many years later Bob Brown told me to "concentrate on the significant few" and to

"find the assignable cause." I realize now, that's what the planners were doing then.

Not only didn't the replenishment group seriously use Distribution's computer

forecast, neither did most of the rest of Distribution. Anyone who needed one did his

or her own, which by magic yielded results they liked. For the major SKUs they had

the Operations Services group run them on commercial timesharing using, you

guessed it: Exponential smoothing with auto-correlation to de-seasonalize the data.

Marketing and Sales were not much impressed either. They had a method they were

quite comfortable with. Their first step was what the academics call Judgmental or

Exogenous, and what I like to call a Causal model.

Infant formula was a major product in those days, as it is now. They individually

predicted market-share, fertility rates, women of childbearing age, percent of babies on

formula, length of feeding, hospital beds, and product mix. With these and a few other

secret ingredients, like gut-feel and just plain guts, they generated a forecast. He who

lives by the crystal ball however, must learn to eat glass.

The Division President usually didn't like their forecasts. He had his own method. In

effect, he would put two points on a graph, one where we were at the time and one

where he wanted to be. He drew a straight line between them and said "that's the

forecast"... and behold! It was unanimously adopted by Marketing and Sales, who

quickly found some earlier "error" in their thinking. When I was working at Ross part-

time after school, I remember horse-laughing this seemingly unscientific example of

benevolent dictatorship. I learned something though. It took a while, but I figured it

out. This technique, which I like to call forecasting by desire, works. The president was

setting a goal. The goal was adopted as the forecast. The troops busted their necks to

make that "forecast" happen, and by George it did! Distribution grumbled, but stuck

with its independent statistical systems. No one objected. No one outside Distribution

really used them or needed to see them anyway.

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 6 of 14

In the late '70s we realized we needed better distribution forecasts. Well, we sort of

realized. Our growth overwhelmed the time available for optical techniques. Service

and inventory were getting more expensive and harder to manage. The problem

actually surfaced as a question of how to handle field replenishment in true multiple

plant environments. To replenish, we needed new stocking strategies. Working stock is

easy. It's just a function of replenishment quantity and usage ... which is always linear

and consistent right? Safety stock is easy too. Just set it to say, two weeks maybe? If

we had to, we knew we could get stuff anywhere in two weeks. Multiplant? Piece of

cake. No product was made at more than 2 plants. That way conveniently, "Who

makes what", was fairly straightforward. ("Straight forward"...that's OSU-ish for

"obvious to the intelligent but not always to me".)

Twenty-five products at forty-five locations and not full dense. A 1000 SKUs are not

unmanageable manually. The logic begins to fall apart at 3 plants producing any one

product and wallows at 4. Grow it to 35 or 40,000 SKUs and the green visors begin to

melt. The best sources told us that to have a good replenishment system you need a

good inventory planning system based on service. To have a good inventory planning

system you need good forecasts. Ah! A reason to forecast.

Like all progressive American World-Class corporations we waited way too long until

we were in a good deal of pain before we began work overhauling our forecasting and

inventory planning system. We spent almost a year looking at every causal and time

series technique under the sun... averages, moving averages, weighted moving

averages, auto regressive moving averages, exponential smoothing, Fourier series, and

Box-Jenkins. We even sponsored a Ph.D. dissertation in Delphi Methods. One popular

vendor said "Do them all, then average the answers." Very democratic.

We selected a technique that was at the time the best combination we could find of

accuracy, speed, efficiency, and economy. I had a boss/mentor some years ago who

gave me a sign that still hangs in my office. It says, " Good, Fast, or Cheap... pick any

two. " We picked Fourier Series, installed it, and then paid our dues on the learning-

curve roller coaster. The system has provision to input information from other sources

and blend it with the statistical forecast. Our own systems folks, consultants, software

vendors, and amazingly the Distribution department users, all agreed it was working

right and working well.

Now that we had the "right" answers we felt this driving "need" to spread the truth as

we knew it to other company functions. Forecast missionaries, if you will. Reception

ranged from lukewarm to hostile. For some reason, other areas wanted to continue to

use their own methods. While everyone one was supportive of our efforts and provided

all the "information" they could, they just didn't want to use our forecast. Why? Simple

really, we had forgotten something we learned while we were evolving our own

"integrated" forecast.

FORECASTS

"Partly cloudy, warm and humid... high 83 ... chance of afternoon

thundershowers... chance of rain is 20 percent. Winds from the West 10

to 15 miles per hour. Sunset 8:43 PM."

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 7 of 14

Doesn't sound too bad for a Sunday afternoon in Ohio, does it? Did you ever notice

that most of our decisions concerning weather are binary? They boil down to a "go" vs.

"no-go". You will golf in the rain ... maybe. You won't in a thunderstorm. Some paints

cannot be applied at temperatures over 80 or below 40. The family reunion at Duncan

Run Park should be okay. Should you spray the fruit trees this morning? The labe l

says winds must be under five. The National Weather Service can tell you what time

the sun will set EXACTLY. Does anyone here need to know or care to know exactly?

Probably only Count Dracula.

The most striking thing about a weather forecast is that it is remarkably hardly ever

goal-oriented. Good weather forecasters do not bet on the weather.... they bank on the

climate. They can't influence a thing. Not true of business forecasters.

Business forecasts are for the most part intensely goal oriented. Unlike the

weatherman, business banks on the weather and bets on the climate. There are built-

in incentives to over-forecast when setting up annual expense budgets and to under-

forecast when setting sales or other performance "goals."' The operating climate out

five days, months, or years can't be relied upon to be basically the same as it is today.

Percent sunshine (I love that one nearly as well as "percent chance of rain") can't be

influenced by the Weather Bureau. Sales performance darn well can be influenced by

effort. We can change the future. As a matter of fact, a large part of any business'

employees are expected to and paid to do just that. Businesspeople can actually move

sunshine from Fiscal Year '92 back to Fiscal Year '91. Well, some can anyway. Magic!

Operations forecasts are much, much less goal oriented. The forecasts are at the same

time politically simpler, and paradoxically, mechanically more complex. The

Operations manager is usually more concerned with accuracy and not with

attainment.

FORECASTING IS AN ART

Forecasting is an art, it is not a clear-cut science. Both the prophets of Marketing who

tend to work with causes and gut-feel, and the computerized statistical forecasters in

Operations, who tend to work with history, are still just guessing. Users need to

recognize that statistical history based forecasting is like driving a car on a country

road with the windshield blacked out and only having a rear view mirror to steer by. In

business, we talk about and treat forecasting as a science. But it is still an art, an art

assisted by science.

Let's take a brief look at some of the areas that in many companies may have their

own forecast.

MARKETING

? Very broad, trend oriented.

? Either oblivious to geography or at best interested in large areas like "The

Southeast".

? Forecasts demand, not sales, as well they should.

? Strategies can influence demand and/or sales.

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 8 of 14

? Competition sensitive (share).

? Time frame is often quarters or years.

? Horizon is at least 3 to 5 years. Bulk of effort is expended on 1 to 2 years out.

? Penalty for over-forecasting is much higher than for under-forecasting.

? There is no financial incentive to over forecast, but great political pressure to do so.

? Very goal oriented.

? Units are dollars, pounds, etc.

SALES

? Broad, trend oriented.

? Performance oriented.

? Geography is very detailed for performance and compensation but for little else.

? Strategies influence demand as well as sales.

? Internal competition is high.

? Time frame is day, week, month, etc.

? Horizon is month or quarter or a year or two at most.

? Penalty for over-forecasting is extremely high. There is strong incentive to under-

forecast.

? Highly goal oriented.

? Units are dollars, pounds, etc.

FINANCE

? Broadest of all areas. To survive, the business needs to make a profit, "make plan."

? This area has the greatest number of knobs to twiddle. Profit not making forecast?

The price can be changed with elasticity deciding the direction. Income and costs

can be cut or to some degree moved "elsewhen".

? Insensitive at best or absolutely numb to geography.

? Time buckets broad, with quarters or years preferred.

? Low sensitivity to mix other than as mix effects cost or revenue.

? Long horizons up to 10 years or even more.

DISTRIBUTION

? Among the least goal oriented, relative to forecasts.

? In many firms, has to be disaggregated from marketing or sales forecasts to get

time, place, and exact product mix.

? Accuracy determines ability to control costs and maintain service (field

replenishment, freight budgets, warehouse rate negotiations, short-date control.)

? Penalty for under-forecasting is greater than for over-forecasting.

? Product mix, geography, and timing are of crucial importance. Operationally, the

time bucket is usually weeks or months, although planning on a daily level is

becoming more common.

? Monthly or weekly forecasts are often spread to days.

? Short horizons of 3 months or less are common.

? There is normally no incentive to hedge operational forecasts other than for

budgets or other performance measures.

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 9 of 14

Other areas that may make their own forecasts, formal or informal include:

BUSINESS MODELING

BUSINESS PLANNING

COMPETITIVE or MARKET ANALYSIS

EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT

LONG RANGE PLANNING

PRODUCTION PLANNING / SCHEDULING

PURCHASING

STRATEGIC PLANNING

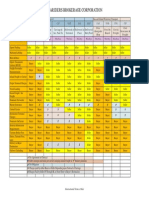

PICKING A METHOD

There are many issues you have to consider in picking a method or a structure for

your forecast. For the Management Science and Operations Research folks it's often

very easy to focus on mechanics and accuracy, but that's not the whole picture. Lets

invert the mental matrix we just discussed and make the columns into the rows.

SCOPE: How widely is your forecast used? Only by you, a department, a major

functional area, the division, or corporate wide? You need to know who is going to be

quoting you... sometimes inappropriately.

GEOGRAPHY: It is a good idea to work with the largest aggregated division you can.

The top-down folks tell us that if you can get away with a national forecast, do it.

There are two problems with this advice. First, someone else may need more

disaggregated numbers than you do. For example, a national forecast by quarter is

nearly useless for distribution and production planning. Conversely, there may be

grassroots information in disaggregated or local forecasts that when rolled up will give

you a better national forecast than a national model can. This takes some

experimentation. Don't be shy, try it.

SURROGATES: Not all variables are accessible. Everybody talks about demand

forecasting but what they really mean and usually forecast are sales. Do you forecast

dollars or units? What do price changes do to each of those? Are your sales net of

returns? What about sales in one time period from one warehouse that are returned in

another time period at a different warehouse? Yes Virginia, there can be negative

forecasts and a lot of our lovely mathematics can't deal with them.

INFLUENCING: If a forecast can be influenced or the future changed, than a good

businessman or woman will do it. These forecasts must be monitored more closely

than the statistician or mathematician thinks. Leak word to the marketplace of an

impending shortage and a shortage will very likely be created. The classic case is the

new freeway designed at 4 lanes to cover "current and projected" growth that is

overloaded the very day it opens. It's simply there now, and people who were not

counted in the original traffic survey go miles out of their way to use it.

HORIZONS: Operations people, Distribution, Production, and the like, tend to set

their horizons too far out. Operations folks make the mistake of trying to use their

short-term model to advise the marketing and financial folks what they should be

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 10 of 14

doing and the marketing and financial folks don't see why the Distribution department

has to have its own forecast anyway. Hey, we are doi ng five -year plans aren't we?

Operations might need a longer-range tool for their resource and capital budgeting but

they still try to get their short term forecast to do the job. A planning horizon is like a

diving board. If you jump up and down on the end, there is a lot of slop. Backup to

near the pivot point and there is a lot less range when you jump. Another way to view

this is to think of it as choking up on a baseball bat. You gain control but lose power.

People confuse forecast lead-time with forecast horizons. It has been a while since I

worked with birth statistics directly, but when I did the Census Bureau was up to a

year behind issuing data. If I wanted to forecast one year out, by month, and the data

is 6 months behind, then I really have to forecast 18 months, 6 of which are lead-time

and 12 the horizon.

GOALS vs. PREDICTION: This is really a question of attainment versus accuracy.

When a company hits its forecast it doesn't stop there. For business, a forecast is

something to make and then to beat. I think of forecasting as the casting forward of

old data. Prediction on the other hand, is the integrated result of combining all

sources of knowledge about the future.

POLITICS: It is human nature to negotiate reachable goals when it's your goals being

set. Your pay and performance depend on it. It is good management to recognize this

and build stretch into the goals we set for others, but not too much because we get

measured on whether they meet their goals. Everybody likes a safety factor. We might

as well accept the fact that forecasts are very often negotiated. Some forecasts or

predictions are so cut and dried, they really ought to be called policies.

VOLUME: Don't forget the green visor types with the Monroe -mechanical calculators.

Be prepared to accept the fact that certain areas have to give up accuracy just to cope

with the timeliness and volume issues, and just to get the job done.

Computers can build and process models at astounding rates and update them even

faster. Forecast accuracy has to be managed. People-resources are scarcer than CPU-

resources. A firm with several hundred thousand forecasts has to select meaningful

measures, decide what is significant, and concentrate on correcting problems so they

don't pop up again.

UNIT OF MEASURE: This is nearly an insurmountable problem. Some functions need

data in units or cases while others need dollars, hundredweight, shifts, truckloads,

railcars, etc. What is quite sensible to one area may sound like measuring speed in

furlongs per fortnight to someone else. My favorite is "powder pounds fed per sales

day." It is perfectly useless for operations, but our sales force doesn't think it's so

useless. Why? That's how they earn their bonuses.

Computerization has forced some uncomfortable but "logical" measures on all of us.

MRP and DRP need uniform time buckets. In some firms, the pain of coping with the

discipline of thirteen 4 week periods is so extreme that the system is installed on a

weekly or daily basis, and then aggregated up into 4 week buckets just to avoid the

pain of time period reconciliation.

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 11 of 14

DEPENDENCY: Don't assume its "wrong" to forecast something that is correlated to

another variable just because you don't see the correlation. Your user might be right.

In the 60's, the practitioners laughed at including moon phases in causal models of

births. Many hospitals now staff their obstetric units by moon phases.

Forecasting "experts" usually err the other way. Practitioners like to use correlation of

dependent variables to "improve the forecast." An example of this is our hospital

bottles and nipples. Bottles are packed 24 to the case and nipples packed 500. The

usage correlation is nearly is perfect but safety stocks set this way can be disastrously

wrong. The problem is in the high variance, not the overall accuracy. Safety stocks are

set on variance and overall accuracy is of no great benefit. Some years ago, a colleague

of mine at another division of Abbott mentioned that they could never explain the poor

correlation between IV (intravenous) solution needle sets and extension tubing kits.

Extension tubing use was so heavy that they increased the length of the tube on the

standard sets several times but to no avail. They just refused to forecast them

separately. Anyone who has worked around an emergency or rescue squad could have

told them that knotted tubing is ideal for securing things onto a patient in a wet

environment where adhesive tape just won't stick. Simply a use for tubing that the

manufacturer never thought about.

AGGREGATION: We have probably beaten this point to death in earlier parts of our

discussions. Just remember the three management variables are time, geography, and

stock keeping unit. Aggregating is easy and disaggregating not so easy.

DATA QUALITY/AVAILABILITY: You don't realize how scarce decent data is until you

try to use the data you have. In our early days, Ross threw out valuable usage history

because an the MIS tape retention policy was set to two years per standards. What a

loss. The very first models we ran found data that was wrong and had been for years.

It was not corrected because the totals "tied" on the accounting reports. No one needed

it before now.

Some items are still only tracked by sales territories, which may be very fluid year to

year. Even when stable, they don't align at all with the warehouse service boundaries.

In your shop, is the data "net of returns" or "net of credits?" I bet not, very few are. Is

that truckload order for Brooklyn, NY that was shipped from Boston instead of from

Jersey City (because we were low on stock) now going to hose up both forecasts?

Marketing departments in many organizations just do not retain geographic data. All

our great techniques are of little value if the organization won't invest in the care and

feeding of the database.

MISCELLANEOUS ISSUES: Invest time in understanding both the real and the

perceived penalties for error, especially those unspoken penalties. Find a blend of the

scientific and the touchy-feely. The Delphi researchers have proved countless times

that the organization knows a lot more than we think it does or even it thinks it does.

Its "pieces-parts" just don't communicate very well. Last and by no means least, be

sure to account for all the built-in incentives various business functions have to mis-

forecast. It may not be controllable but it must be understood.

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 12 of 14

CONCLUSIONS

Common sense tells us certain areas must have the same forecast. There is no sense

to Distribution planning to ship product that Manufacturing just is not going to make.

Unreconciled differences between Production and Distribution negate the benefits of

the best DRP or Fair-Shares Allocation system. There is no sense to Manufacturing

planning to build inventory to cover an annual plant shutdown that Purchasing

cannot cover because they use a different forecast. Unreconciled differences between

Production and Purchasing can negate the benefits of the best MRP systems.

A similar case can be made for Marketing, Sales, and Product Development. They have

to use the same script.

Over the years, I've modified my dream of having one script. I don't think it should be

done and I don't think it can be done. Sadly, the organizations that have gone to one

forecast by edict are the ones that often have the most diverse ad hoc forecasts being

used underground.

I believe the answer is to determine where needs are similar and where they differ and

then to form logical nodes that do use a common forecast or a translation of one. We

see our company as having three basic forecasting nodes or teams:

OPERATIONS:

Production Planning

Inventory Planning

Purchasing

Distribution

Manufacturing

MARKETING:

Marketing

Sales

Product Development

Distribution

Pricing

Business Modeling

FINANCE:

Financial Planning

Long Range Planning

Econometrics

Business Modeling

Business Modeling appears in two teams. In some companies it is part of Finance

while in others it is part of Marketing. Regardless of its place on an organizational

chart, it links Finance and Marketing. In a like manner, Distribution appears in two

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 13 of 14

teams. Classically thought of as part of Operations, Distribution is functionally an arm

of Marketing. Regardless of formal chart position, it links Marketing and Operations.

Within each of these three major teams information MUST be accessible and freely

traded. Departments that are group members must convince each other and

themselves that it is counterproductive to nurture "private" forecasts.

Something to keep in mind: If Purchasing is forecasting sales or product mix on its

own, it is because it knows something or needs something that Production Planning

doesn't. You can bet Production ought to know about it also.

Managerially, the point is simply that reconciliation is a means... not an end. The

exami nati on and di scussi on process i tsel f wi l l create more i ntegrati on than

forci ng the group members to adopt a common forecast ever wi l l .

THE [IM] POSSIBLE DREAM:

Having the choir sing off the same script may or may not be reachable. In a large

organization it may not be practical. The overall strategy for managing the forecast

problem is to:

Identify the demand variables you can control. CONTROL them.

Identify who or what controls what's left. INFLUENCE them.

Identify whatever is left over and FORECAST it.

If the three forecast teams are stable, then there is real opportunity between the

groups for a combination clearinghouse and traffic cop. This cop can be an individual

or a group. If a group, it can be independent or made up of members from the original

three teams. Regardless of structure, like the forecast team, the cop's job is to:

? Translate definitions and data.

? Warn of dissension adverse to the whole

? Reconcile differences when necessary

The payoff is subtle. Effective organizations are more efficient. Service can improve

while costs go down. As professional forecasters and predictors, we are not victims of

the unknown. We can change the future.

CARPE DIEM

Demand Forecasting: Reality vs. Theory Page 14 of 14

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

When I was a high school senior armed with a used paperback copy of "HOW TO BUY

STOCKS", I started buying stock two or three shares at a time. I did it by telephone

with an out-of-town broker who did not know I was a minor. With some of the

questions I asked, he had to suspect. A big buy for me was three shares of Random

House at $9.

On one occasion I asked him what he thought the market was going to do. Not just a

little abruptly he replied, "Hell, you're the market.... what do YOU think?"

Wel l , what do you thi nk i s goi ng to happen to demand

for ecasti ng practi ces i n the next ten years?

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (265)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (890)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Cambridge Ielts 1 and 2 Writing Task With AnswersDocument21 pagesCambridge Ielts 1 and 2 Writing Task With AnswersMohammad Monir53% (15)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- US Navy Cold Weather Handbook For Surface ShipDocument236 pagesUS Navy Cold Weather Handbook For Surface Shipnicholas lee100% (2)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Guidelines For Float Over InstallationsDocument36 pagesGuidelines For Float Over InstallationsClive GouldNo ratings yet

- MCRP 3-10e.8 FRMLY 3-16.5Document271 pagesMCRP 3-10e.8 FRMLY 3-16.5Matheus MarianoNo ratings yet

- Coast Artillery Journal - Aug 1946Document84 pagesCoast Artillery Journal - Aug 1946CAP History Library50% (2)

- Sample Warehouse Training PacketDocument21 pagesSample Warehouse Training Packetbarath1986100% (4)

- Logistics Infrastructure By2020 Fullreport PDFDocument72 pagesLogistics Infrastructure By2020 Fullreport PDFshwetaplanner7959No ratings yet

- How Can We Improve Agriculture, Food and Nutrition With Open Data?Document34 pagesHow Can We Improve Agriculture, Food and Nutrition With Open Data?Open Data Institute100% (1)

- The New Age of AnalyticsDocument9 pagesThe New Age of Analyticsbarath1986No ratings yet

- GRE Concordance InformationDocument2 pagesGRE Concordance InformationIshtiaqAhmedNo ratings yet

- Bentley University Campus Map: Boston Minutes AwayDocument1 pageBentley University Campus Map: Boston Minutes Awaybarath1986No ratings yet

- NewGRE WordsDocument7 pagesNewGRE WordsMatt Daemon Jr.No ratings yet

- Understanding Plastic CodesDocument1 pageUnderstanding Plastic Codesbarath1986No ratings yet

- OSU Transcript Services SummaryDocument1 pageOSU Transcript Services Summarybarath1986No ratings yet

- Arvato - JD of Project ExecutiveDocument1 pageArvato - JD of Project Executivebarath1986No ratings yet

- MSc Global Logistics Course DescriptionsDocument1 pageMSc Global Logistics Course Descriptionsbarath1986No ratings yet

- Shanghai Rolex Masters: City, Country Tournament Dates Surface Total Financial CommitmentDocument1 pageShanghai Rolex Masters: City, Country Tournament Dates Surface Total Financial Commitmentbarath1986No ratings yet

- Background & Requirement: Need To Find Supplier List and Price Quotes For TheDocument1 pageBackground & Requirement: Need To Find Supplier List and Price Quotes For Thebarath1986No ratings yet

- Metal Works InstructionsDocument2 pagesMetal Works Instructionsbarath1986No ratings yet

- Traditional Procurement ProcessDocument2 pagesTraditional Procurement Processbarath1986No ratings yet

- Background & Requirement: A Client Based in USA Which Is in The Business ofDocument2 pagesBackground & Requirement: A Client Based in USA Which Is in The Business ofbarath1986No ratings yet

- ZinnDocument5 pagesZinnbarath1986No ratings yet

- Traditional Procurement ProcessDocument2 pagesTraditional Procurement Processbarath1986No ratings yet

- Excel Practice SheetDocument3 pagesExcel Practice Sheetbarath1986No ratings yet

- Analysis & Design of Logistics Systems - Winter '09Document4 pagesAnalysis & Design of Logistics Systems - Winter '09barath1986No ratings yet

- Excel Practice SheetDocument3 pagesExcel Practice Sheetbarath1986No ratings yet

- Nokia E71x User GuideDocument60 pagesNokia E71x User GuidealwaysanybodyNo ratings yet

- Incoterms 2011Document1 pageIncoterms 2011barath1986No ratings yet

- Career Strategies MbaDocument2 pagesCareer Strategies Mbabarath1986No ratings yet

- Master of Business Logistics Engineering Degree Audit: Required Courses (9) Qtr/Yr Hours GradeDocument1 pageMaster of Business Logistics Engineering Degree Audit: Required Courses (9) Qtr/Yr Hours Gradebarath1986No ratings yet

- Grad Networking Presentation WI 09Document15 pagesGrad Networking Presentation WI 09barath1986No ratings yet

- An Introduction To Case InterviewsDocument6 pagesAn Introduction To Case Interviewsbarath1986No ratings yet

- Value Stream Mapping - Gaining TractionDocument24 pagesValue Stream Mapping - Gaining Tractionbarath1986No ratings yet

- Login to View ProductsDocument2 pagesLogin to View Productsabdur rahimNo ratings yet

- English VocabularyDocument66 pagesEnglish Vocabularyhanh nguyenNo ratings yet

- Notice of Race Vendee Globe 2024 2025Document29 pagesNotice of Race Vendee Globe 2024 2025Neil ClatworthyNo ratings yet

- 2010 LYS-5 İngilizce Testi SorularıDocument9 pages2010 LYS-5 İngilizce Testi SorularıPascal NoumaNo ratings yet

- Weather CourseDocument4 pagesWeather CoursepraschNo ratings yet

- Using WRF Model To Forecast Airport VisibilityDocument5 pagesUsing WRF Model To Forecast Airport VisibilityHong NguyenvanNo ratings yet

- Js ProjectDocument7 pagesJs ProjectNTM SOFTNo ratings yet

- UNIT 19, 20 Des B2Document19 pagesUNIT 19, 20 Des B2Anh Trần ViệtNo ratings yet

- PPT05-Quantifying UncertaintyDocument39 pagesPPT05-Quantifying UncertaintyVeri VeriNo ratings yet

- Weather Cape Town - Google SearchDocument1 pageWeather Cape Town - Google SearchDaylen OosthuizenNo ratings yet

- Rainfall Measurement and Flood Warning Systems A ReviewDocument11 pagesRainfall Measurement and Flood Warning Systems A Reviewishishicodm.08No ratings yet

- 50 Sample Answers For IELTS WritingDocument53 pages50 Sample Answers For IELTS WritingNovák ÉvaNo ratings yet

- Seasonal Assessment of Resource Adequacy For The ERCOT Region (SARA) Winter 2022/23Document21 pagesSeasonal Assessment of Resource Adequacy For The ERCOT Region (SARA) Winter 2022/23Rebecca SalinasNo ratings yet

- KNMI Corporate Brochure ENGDocument12 pagesKNMI Corporate Brochure ENGAnonymous xrXuqD0JNo ratings yet

- CFD Fall 2009 Course OverviewDocument18 pagesCFD Fall 2009 Course OverviewSiva Ramakrishna ValluriNo ratings yet

- Docen BFormatDocument8 pagesDocen BFormatb292442No ratings yet

- Hourly Solar Irradiance Time Series Forecasting Using Cloud Cover IndexDocument13 pagesHourly Solar Irradiance Time Series Forecasting Using Cloud Cover IndexAditya PatoliyaNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Dynamics® AX: Demand ForecastingDocument13 pagesMicrosoft Dynamics® AX: Demand ForecastingAkram MalikNo ratings yet

- Salt Fire - August 29, 2011: USDA Forest Service Intermountain Region 4 Salmon-Challis National ForestDocument31 pagesSalt Fire - August 29, 2011: USDA Forest Service Intermountain Region 4 Salmon-Challis National ForestFG SummerNo ratings yet

- Reliability Based Transmission Capacity Forecasting: CIGRE 2018Document8 pagesReliability Based Transmission Capacity Forecasting: CIGRE 2018luisrearteNo ratings yet

- Identified Social ProblemDocument10 pagesIdentified Social Problema kNo ratings yet

- Manual On Flood Forecasting and WarningDocument142 pagesManual On Flood Forecasting and Warningalmutaz9000No ratings yet

- MT 25 QTR V1 2021 PDFDocument12 pagesMT 25 QTR V1 2021 PDFNghia ChuNo ratings yet

- AWC - METeorological Aerodrome Reports (METARs)Document2 pagesAWC - METeorological Aerodrome Reports (METARs)JOSE MORLES100% (1)