Professional Documents

Culture Documents

A Project Report ON World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

Uploaded by

Palash Jain0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

541 views22 pagesmn

Original Title

Environmental Law

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentmn

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

541 views22 pagesA Project Report ON World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

Uploaded by

Palash Jainmn

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 22

1

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

A

PROJECT REPORT

ON

WORLD TRADE ORGANISATION AND PROTECTION OF

ENVIRONMENT

PROJECT SUBMITTED TO:

Mr. Azim Pathan

Faculty of Environmental Law

H.N.L.U

PROJECT SUBMITTED BY:

Palash Bakliwal

4

th

Semester

Roll no-87

B.A. LL.B. (Hons.)

H.N.L.U

HIDAYATULLAH NATIONAL LAW UNIVERSITY, RAIPUR

CHHATISGARH

2

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

TABLE OF CONTENTS-

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 3

OBJECTIVES 4

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 5

INTRODUCTION 6

TRADE IMPLICATIONS OF CLIMATIC CHANGE 8

PROTECTION OF ENVIRONMENT AND TACKLE CLIMATE

CHANGE WHILE MAINTAINING TRADE OPEN 9

ARTICLE XX OF GATT/WTO 10

PRODUCTION AND PROCESS METHOD 14

GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES AND OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL

PROVISIONS 16

CONCLUSION 18

REFERENCES 21

3

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS-

I would like to take this opportunity to express my deep sense of gratitude towards my course

teacher, Mr. Azim Pathan for giving me constant guidance and encouragement throughout the

course of the project.

I would also like to thank the University for providing me the internet and library facilities

which were indispensable for getting relevant content on the subject, as well as subscriptions

to online databases and journals, which were instrumental in writing relevant text.

Palash Bakliwal

4

th

Semester

4

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

OBJECTIVES-

The main objectives of this project are-

1. To study the trade implication of climatic change.

2. To study the protection of the Environment and tackle climate change while maintaining

trade open

3. To understand Article XX of GATT/WTO.

4. To know the production and process methods of different products.

5. To study the Government Subsidies and other Environmental provisions

5

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY:

This research paper is descriptive & analytical in approach. It is largely based on secondary

& electronic sources. Books & other reference as guided by faculty of Environmental law are

primarily helpful for the completion of this project.

6

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

1. INTRODUCTION-

In these we would be showing the Interrelation between WTO and Environment. A

growing number of developing countries look to trade and investment as a central part of

their strategies for development, and trade considerations are increasingly important in

shaping economic policy in all countries, developed as well as developing. At the same time,

however, most of the worlds environmental indicators have been steadily deteriorating, and

the global achievement of such important objectives as the Millennium Development Goals

remains very much in doubt. These trends are not isolated; they are fundamentally related.

Much environmental damage is due to the increased scale of global economic activity.

International trade constitutes a growing portion of that growing scale, making it increasingly

important as a driver of environmental change. As economic globalization proceeds and the

global nature of many environmental problems becomes more evident, there is bound to be

friction between the multilateral systems of law governing both. As the integration of trade

and environment is inevitable in practice, a proper framework within the WTO mechanism

itself is essential to strike a balance between the two. The contention of critics of the WTO

1

is

that the Organization is inadequate for the purposes of protecting the environment. This is not

so. The WTO gives great latitude to members to restrict trade to protect the environment.

This is rarely conceded. There are several provisions in the WTO agreements dealing with

environment. There is a reference to sustainable development as one of the general objectives

to be served by the WTO in the Marrakech Agreement which established the WTO. There are

provisions in the Agreement on Agriculture and the General Agreement on Trade in Services

(GATS). However by far and away the most important provisions as far as environmental

issues are concerned are Article XX of the GATT and the Agreements on Sanitary and

Phytosanitary Measures and the Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade. However

existence of uncertainties, ambiguities and conflict situation between WTO and environment

is not denied. There are certain grey areas which require attention and they had been subject

matter of debate between countries at international negotiations and before the WTO dispute

settlement body. Conflict of relationship exist between Multilateral Environmental

Agreements (MEAs) and WTO. Relationship between the two is still to be clarified. Such a

conflict creates legal insecurity and is injurious to the world trading system. WTO though

1

The main critics of the WTO are a vast array of environmental, conservation and public policy NGOs and

organizations such as Public Citizen, Greenpeace, One World, World Wildlife Fund, Friends of the Earth, Sierra

Club to name a few.

7

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

specifically meant for trade and not for managing environment has no option but to realize its

international public policy objective. Provisions within the covered Agreements pertaining to

environment normally provided in the form of exceptions are itself suffering from

interpretation problems, which is clearly evident from various disputes before the WTO

dispute settlement mechanism. Review of cases in which panel and appellate body ruled on

environmental matters suggests that current legal instruments are not sufficient for

environmental concerns. Article XX of GATT affirms the legal right of WTO Members to

adopt measures that address environmental issues; WTO is yet to come out clearly on

such environmental obligations.

2

The WTO's Committee on Trade and the Environment

(CTE), for its part, has provided a valuable forum for discussions on reconciling

environmental and WTO treaty obligations and other crossover issues. However, it has not

produced concrete proposals for trade policy reform to enforce or promote environmental

goals. Optimal policy is to have an appropriate environmental policy in place, to look after

the environment, and then to pursue free trade to reap the gains from trade. There are

pragmatic steps that the international community is required to take to more intelligently

ameliorate trade-induced environmental degradation and to better balance free trade with

ecological protection. The links between trade and the environment are multiple, complex

and important. Trade liberalization is of itself neither necessarily good nor bad for the

environment. Its effects on the environment in fact depend on the extent to which

environment and trade goals can be made complementary and mutually supportive. A

positive outcome requires appropriate supporting economic and environmental policies.

2

To an extent Asbestos case, Gasoline case, and shrimp case, the rulings have confirmed that countries can

enact environmental measures, even if they affect trade and even if they concern others' Processes and

Production Methods.

8

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

2. TRADE IMPLICATIONS OF CLIMATE CHANGE-

There are no rules in the WTO specific to climate change. However, the WTO tool box of

rules can apply. The WTO provides a legal framework ensuring predictability, transparency

and the fair implementation of such measures.

Climate change has an impact on various sectors of the economy. Agriculture, forestry,

fisheries and tourism are affected by climate change through temperature increases, droughts,

water scarcity, coastal degradation, and changes in snow cover. These are key sectors in

international trade especially for developing countries which have a comparative advantage

on the international trading scene. Extreme weather can also affect ports, roads, airports and

railways. Climate change can disturb supply and distribution chains, potentially raising the

cost of international trade.

Trade itself can also have an impact, positive or negative, on CO2 emissions. Economic

development linked to trade opening could imply a greater use of energy leading to higher

levels of CO2 emissions. However, trade opening has much to contribute to the fight against

climate change by improving production methods, making environmentally friendly products

more accessible at lower costs, allowing for a more efficient allocation of resources, raising

standards of living leading populations to demand a cleaner environment and by spreading

environmentally friendly technologies.

In addition, about 90% of trade is carried out through maritime transport, which is the lowest

contributor to CO2 emissions. It represents less than 12% of the transport sector's

contribution to CO2 emissions, while road transport represents about 73%. Trade can help

countries to adapt to climate change. When countries are faced with food shortages brought

about by climate change, trade can play the role of a transmission belt between supply and

demand.

In the last decade, countries have designed new policies to address climate change. They

range from standards to subsidies, from tradable permits to taxes. In doing so, governments

have to find the right balance between designing a policy that would impose minimal costs

for the economy while effectively addressing climate change. The industrial sector's growing

concern is to remain competitive while climate mitigation efforts proceed.

Today, some governments may be considering the use of trade measures in the fight against

climate change. Border measures may be envisaged to imported products based on their

carbon footprint. Several countries have raised this issue within the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) negotiations.

9

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

The details of how that footprint would be calculated in an increasingly globalised market,

where products are manufactured in a number of different countries is also part of the debate.

Global problems like climate change require global solutions which must be based on the

well-known environmental principle of "common but differentiated responsibility" which

means taking into account different level of responsibility in emissions.

3. PROTECTION OF ENVIRONMENT AND TACKLE CLIMATE CHANGE

WHILE MAINTAINING TRADE OPEN-

Rules made by WTO provide significant scope to protect the Environment and tackle climate

change while maintaining trade open like. In the preamble to the Marrakech Agreement that

established the WTO, sustainable development, and the protection and preservation of the

environment are recognised as fundamental goals of the organization. The WTO promotes more open

trade with a view to achieving sustainable development. It provides WTO members with the

flexibility they need to pursue environmental and health objectives. A distinction should be made

between trade measures with a genuine environmental goal, and measures that are intended as

disguised restrictions and are applied in an unjustifiable and arbitrary manner.

Specific conditions where trade restrictions are allowed-

The WTO is not an environment agency. The main objective of the WTO is to foster

international trade and open markets but WTO rules permit members to take trade restricting

measures to protect their environment under specific conditions. Two fundamental principles

govern international trade: national treatment and the most favoured nation (MFN).

National treatment means any policy measure taken by a member should apply in the same

way whether the good is imported and produced domestically. Provided they are similar

products imports should not be treated less favourably than domestic goods.

The MFN principle means that any trade measure taken by a member should be applied in a

non-discriminatory manner across to all countries.

The WTO rule book permits governments to restrict trade when the objective is protecting the

environment. The legality of such restrictive measures depends on a number of conditions

including whether they constitute justifiable discrimination. These measures should not

constitute disguised protectionism.

In the preamble of the Marrakech Agreement, which established the WTO, sustainable

development, the protection and preservation of the environment are recognised as

fundamental goals of the WTO. Article XX of the GATT (General Agreement on Trade and

Tariffs) lists exceptions to open trade, among them the protection of the environment. WTO

10

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

jurisprudence has regularly reaffirmed members' right to determine their own environmental

objectives. While there may be conflicts between international trade and the protection of the

environment, WTO agreements permit exceptions to trade principles. Every member is free

to determine its appropriate level of protection but must do so in a coherent manner. If a

country bans the importation of asbestos from another, for example, it must ban asbestos

imports from all countries, as well as banning domestic sales. Countries may also use

technical environmental standards or sanitary and phytosanitary measures when pursuing

their environmental objectives. They may, for instance, impose labelling requirements on a

certain category of products. These technical standards could constitute an unfair obstacle to

trade if they are applied in a manner which is discriminatory or if they create unnecessary

obstacles to trade. The WTO encourages governments to apply international standards where

they exist. It is essential for WTO members to be informed of changes in national policies

and to examine whether they are justified. Any draft technical or sanitary standard should be

notified to the WTO.

There is a wider range of WTO rules relevant to climate change. Rules on subsidies may

apply as countries are currently financing the development of environmental friendly

technologies and renewable energy. Intellectual property rules could also be relevant in the

context of the development and transfer of climate-friendly technologies and know-how.

With growing of number of Environmental problems several provisions are included in the

WTO agreement which deals with environment. There is a reference to sustainable

development as one of the general objectives to be served by the WTO in the Marrakech

Agreement which established the WTO. There are provisions in the Agreement on

Agriculture and the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS). However by far and

away the most important provisions as far as environmental issues are concerned are Article

XX of the GATT and the Agreements on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures and the

Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade.

4. ARTICLE XX OF THE GATT-

The core agreement of the WTO system is the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

(GATT). The principal purpose of the GATT was to oblige members to use the same rules to

regulate trade and to ensure in particular that there was no discrimination in trade. All

international agreements need exemptions clauses. These are the mechanisms that ensure that

governments retain the capacity to perform essential functions that might be eroded if the

11

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

basic rules of the treaty are applied. The most common exemption in most agreements is to

preserve freedom of action to protect national security. Article XX specifies what activities

are exempt from GATT rules. These exemptions give members very wide latitude to control

trade to protect the environment.

Article XX waives members of the obligation to apply fundamental commitments,

particularly non-discrimination, in certain cases. They include protection of national

security, protection of morals, and preservation of national cultural heritage. Of

particular importance is the right to waive the rules in order to protect human, animal, plant

health and safety.

Article XX (b) permits restrictions on trade to protect human, animal and plant life health and

safety. Article XX (d) permits restrictions on matters not consistent with the objectives of the

GATT. Article XX (g) also permits restrictions if they complement national programs for

conservation of resources. This is the basis upon which health and quarantine restrictions are

applied to trade in pharmaceuticals, hazardous products, toxic products and products carrying

risk of disease, for example. The capacity of governments to prevent the entry of such

products into their national territory in this way enables governments to maintain the integrity

of national environmental programs in the vast majority of cases. Of necessity, exemptions

clauses must be limited. If they are too wide, they undermine the effect of the principal

provisions of the Treaty. Article XX is limited to a few areas. Members are also bound to

utilize the exemptions only to the extent that it is necessary and are obliged to ensure they are

not disguised restrictions on trade.

The provision relating to conservation of natural resources [Article XX (g)] appears not to

have been drafted with living natural resources in mind; however GATT/WTO panels have

stated that it is reasonable that it should be so interpreted.

3

Experience with use of Article XX of the GATT over many years revealed weaknesses in

some provisions, particularly where the latitude to act was so wide that governments used the

provisions to secure economic protection. Actions were taken to reduce the amount of

discretion governments had to restrict trade. Many countries used the quarantine provisions to

secure economic protection rather than to protect health and safety. The SPS Agreement was

3

This was stated in the second Tuna/Dolphin panel report, although that report was never adopted and it was

restated in the Shrimp/Turtle panel report. United States Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp

Products WT/DS58/AB/R. 12 October 1998.

12

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

negotiated in the Uruguay Round

4

to contain such abuse. It states that if countries base

restrictions on trade on recognized international standards,

5

the restrictions are deemed as

complying with the agreement. Countries could apply other standards, but they were subject

to challenge by other WTO members to demonstrate that they were based on science and

supported by a risk assessment process.

6

The development of the SPS Agreement coincided

with a global trend to shift away from dealing with risk on a no-risk basis to risk

management. The latter approach leads to better use of resources and better enjoyment of

benefits. The requirement that decisions be based on science and a process of risk assessment

introduced transparency into decision-making by creating a visible check on abuse of

executive discretion. This not only protected the rights of members of the WTO, it also gave

assurance to consumers that governments were not abusing their powers.

The Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT) was negotiated in the Uruguay Round,

replacing the Standards Code.

7

It was designed to reduce the scope for countries to use

technical standards as disguised barriers to trade. It obliges members to ensure that national

treatment and non-discrimination apply when technical standards are adopted as mandatory

regulations.

8

Technical standards with restrictive trade effects are permitted for four

legitimate purposes, (including standards developed for the protection of the environment,

for national security requirements, for the prevention of deceptive practices and for the

protection of human health and safety and animal and plant health and life), provided the

effect is not more restrictive than necessary to meet one of those objectives, taking into

account the risk of non-fulfillment. In assessing that risk, the agreement stipulates that

relevant elements of consideration are, inter alia, available scientific and technical

information, related processing technology or intended end uses of products.

9

Members are

also required to base their standards on those developed by international bodies which are

4

Preventing abuse the role of the Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS). The Uruguay

Round of Trade Negotiations, 1986-1994

5

Specifically those set by the International Office of Epizooty (which sets veterinary and animal health

standards), the International Plant Protection Convention (which sets standards for plant health and science

and Codex Alimentarius (a joint organization of the FAO and WHO which sets standards for human health)

6

See Articles 2.2, 3.3 and 5

7

The Standards Code of 1979 was developed in the Tokyo Round of trade negotiations.

8

Article 2.1

9

Articles 2.2

13

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

presumed to be in compliance with the Agreement.

10

In other cases, and where measures have

a significant impact on trade, parties are obliged to notify the measure and provide

opportunities to other WTO members to comment. Sound regulation, standards and eco-

labeling. Making decisions transparent and setting objective criteria by which they could be

challenged as provided or in the SPS and TBT Agreements is consistent with the doctrine that

regulations should be imposed by governments only to protect health and safety. When

Governments regulate for other reasons, they interfere in the market and exercise influence

which favours some parties in the economy and damages others. There is large body of

standards which aim to improve the quality of goods and services and provide information to

consumers. Most of these are national standards and are set by national standard setting

organizations. A set of international standards is produced by the International Standards

Organization. Well-known quality standards developed by that organization include the ISO

9000 series (to improve quality in organizations) and ISO 14000 (to set quality standards to

improve environmental management.). These are voluntary standards and in most countries

are developed by private organizations.

When Governments adopt these standards and make compliance compulsory, they become

official regulations.

11

If a company requires suppliers to comply with specified standards

struck by national standards organizations or ISO, this does not constitute a trade barrier. It is

a commercial requirement. However when a government stipulates that unless such standards

are complied with imports or exports are not permitted, these are trade restrictions that must

comply with WTO rules, including the provisions of the SPS and TBT Agreements. Where

eco-labelling systems are not mandated by governments, but are applied by commercial

entities for the information of consumers, these are voluntary standards and WTO provisions

do not apply.

12

When an eco-label is mandated under government regulation, then the

regulation needs to comply with the provisions of the WTO. As shown in the foregoing, the

10

Article 2.4

11

The WTO Agreement on Technical Barriers to trade differentiates between standards with which compliance

is mandatory, termed technical regulations and standards with which compliance is not mandatory, termed

standards.

12

The Code of Good Practice under the TBT Agreement applies to voluntary standardising bodies and voluntary

standards. There is no legal obligation on these bodies to comply with the Code, however there is an obligation

on the central government standardising body take all reasonable measures to ensure they accept and comply

with the Code. (Article 4 and Annex 3)

14

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

terms of Article XX and of the SPS and TBT agreements make ample provision for use of

eco-labels.

5. PRODUCTION AND PROCESS METHODS-

A complaint about the WTO provisions is that trade restrictions on how a product is produced

or processed are not permitted. The general point was that the WTO did not permit one

member to restrict trade with another on the basis that they did not apply policies which the

first party preferred.

The environmental case is that if one method of processing (such as a method of fishing for

tuna) causes environmental damage (high levels of incidental kill of dolphin) then an

importer should be able to express preference for the product (tuna) processed in a way that

does not cause environmental damage (caught using fishing methods that reduced the

incidental kill of dolphin).

13

WTO provisions generally do not allow trade to be restricted on those grounds. The TBT

Agreement recognizes related processing technology as a relevant consideration for

applying a mandatory technical standard to protect the environment.

However this is a limited application and the extent of its meaning has not been tested. The

general case for not making provision in the WTO for the right to restrict an import according

to the environmental effect of the way in which it was processed or produced is that to do so

assume the WTO should include provisions to secure public policy objectives other than

trade. There is a difference between allowing exceptions to protect national policies and

creating provisions which enable governments to force other to adopt non-trade objectives.

It is argued that the purpose of the WTO is to enable countries to gain the benefits of an open

trading system. If it is to be used as an instrument to achieve environmental purposes, the

case in principle is made for it to be used to secure objectives in other areas of international

public policy such as health, labor standards, postal services, human rights and air transport

standards. If this were to happen, the WTO would cease to be effective in meeting its primary

purpose, not just because it would be overloaded with policy objectives which have not

intrinsic functional relationship to trade, but because giving members of the WTO the right to

pick and choose specific areas in which they could insist on certain standards being met

before trade was permitted would undermine the capacity of the WTO to allow members to

exploit comparative advantage. The case to alter the WTO to permit trade restrictions on

13

Centre for International Environmental Law and Greenpeace International, Safe Trade in the 21

st

Century

A Greenpeace Briefing Kit, September 1999, www.greeenpeace.org accessed August 2001.

15

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

environment grounds is loaded anyway. Those who make that claim are obliged first to

explain why more normal means of achieving international agreement to meet international

public policy objectives are not used. The United Nations Conference on Environment and

Development (UNCED) in 1994 laid down some principles on trade and environment.

14

They

stated that the preferred international approach to protecting the environment was to create

multilateral agreements expressly for that purpose in which members would agree to adopt

commonly agreed measures in their national law or practice. They also stated that use of trade

measures to protect the environment should be avoided. To apply this approach in the case of

the tuna/dolphin issue, rather than have one country threaten a trade sanction unless another

complied with its preferred environmental (fishing) policy (as was the US position) to

achieve international environmental protection, all countries fishing in the region would enter

an international agreement to required their fishing fleets to use the same fishing techniques,

as they now do in a regional fishing agreement.

15

The proponents of the sanction approach would argue that were it not for the coercion, the

regional agreement would not have been adopted. This may be so, but this is to justify the

morally-odious and internationally-censured option of applying coercion because it

disregards the national sovereignty of nations simply on the grounds that the more normal

approach of seeking an international agreement is too slow. In the case of the effect of

dolphin in the Eastern Tropical Pacific region, there was no case for urgency. The species

concerned were not endangered.

Therefore, members of WTO aimed at protecting the environment, subject to certain

specified conditions included in various WTO agreements. Some of these measures are as

under:

(i) Article XX of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), 1994 permits WTO

Members to depart from their GATT obligations for legitimate national policy

objectives. These objectives include:

(a) Article XX (b): Measures to protect human, animal or plant life or health; and

(b) Article XX (g): Conservation of exhaustible natural resources.

(ii) The General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) also contains an exception to

GATT Article XX (b).

14

See Annex The UNCED Trade and Environment Principles.

15

The Agreement on International Dolphin Conservation Program 1999, Inter-American Tuna Commission

16

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

(iii) Article 27 of the Trade Related Intellectual Property Rights (TRIPS) Agreement states

that Members may exclude from patentability inventions, the prevention within their

territory of the commercial exploitation of which is necessary to protect human,

animal or plant life or health or to avoid serious prejudice to the environment.

(iv) Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures (ASCM) contained an exemption

for certain environmental subsidies (provision has since lapsed).

(v) Agreement on Technical Barriers to Trade (TBT Agreement) recognizes protection of the

environment as a legitimate objective and allows Members to take necessary measures

towards this end subject to meeting certain requirements.

(vi) Agreement on the Application of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures (SPS Agreement)

allows Members to use sanitary or phytosanitary measures to protect humans, plants and

animals from contaminants, disease-carrying organisms, and pests. It elaborates rules for

the application of the provisions of Article XX (b).

(vii) The Preamble of the Agreement on Agriculture (AOA) reiterates Members' commitment

to reform agriculture in a manner that protects the environment. Under the agreement,

domestic support measures with minimal impact on trade (known as green box

measures) are allowed and are excluded from reduction commitments. Among them are

expenditures under environmental programmes, provided that they meet certain

conditions.

6. GOVERNMENT SUBSIDIES AND OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL PROVISIONS -

In the Agreement on Agriculture, there is scope to permit subsidies which are for

environmental protection. This was part of the Agreement on Agriculture which was

negotiated in the Uruguay Round. Re-negotiation of that agreement has begun. The European

Union has indicated that it wants general provisions to permit trade restrictions on

environment grounds. Others, such as members of the Cairns Group coalition of agricultural

exporters want to minimize the extent to which such measures can create new grounds for

protection of economic interests. There is a general recognition in the General Agreement on

Trade in Services of sustainable development as an objective of the Agreement.

There is clear evidence around the world that payment of subsidies by Governments

diminishes the regard in which users of resources hold them. Subsidies to farmers encourage

overexploitation of land, subsidies of fertilizers encourage over use, for example causing

excessive levels of nitrates in the water table in European Community farmlands, subsidies to

17

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

forestry and fishery resources result in poor management, and in all these cases, there is

environmental degradation.

The WTO Agreement on Subsidies and Countervailing Measures restricts the extent to which

governments can pay subsidies. It therefore creates a positive framework to foster sustainable

management of resources. It does not apply to subsidies to agriculture which are covered by

the Agreement on Agriculture. Much higher levels of subsidies are permitted in agriculture.

There is a commitment by member of the WTO to negotiate further reductions.

18

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

CONCLUSION-

The literature on the interface of trade and environment, as well as the evaluation of

trade measures within MEAs indicate that trade restrictions are not the only nor

necessarily the most effective policy instrument to achieve the environmental objective

of the MEAs. The root cause of environmentally unsustainable development is the

existence of market or regulatory failures, when the true value of environmental

resources or cost of polluting economic activities are not reflected in market prices

due to structural defects in the system or due to improper government policies. Co-

operative environmental efforts as reflected by MEAs remain important to address

transboundary and global environmental problems, and trade measures can play an

important role in some of these MEAs. Indeed, India noted in an initial paper in 1996

to the CTE that, in dealing with only one element of an MEA, namely, the trade measure, we

may be unconsciously encouraging dependence on trade measures to achieve environmental

objectives, when we are all agreed that this is not the best way of handling environmental

concerns .

Given the rise in environmental consciousness and concerted efforts across the globe to

tackle genuine environmental problems (which defy national jurisdictions) through

MEAs, one cannot disregard trade obligations pursuant to such MEAs within the WTO

especially when those directly relate to certain trade rules. India has recognized the

principle to support environmental initiatives and has been Party to most major MEAs.

At the same time, India recognizes that gains from fair and free trade are important to

support sustainable development at home. The current negotiations on para 31 (i) of the

DMD need to be successfully arrive at an interpretative decision, since it is long

overdue.

Although the present provisions within the GATT/WTO allow for unilateral trade measures

on environmental grounds, a new decision on the relationship between STOs pursuant to

MEAs and rules of the multilateral system is essential to curb the trend in unilateralism.

The jurisprudence in a recent environmental-trade dispute ruling indicates that bilateral

good faith efforts to protect the environment can make departure from free trade

justifiable, since the interpretation of the GATT Article XX provisions has been

significantly broadened (e.g. Malaysia-US Compliance Dispute on Shrimp-Turtle 2001).

19

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

Given the recognition of autonomy of a WTO Member in determining domestic

environmental regulations (which can affect trade with Members), and the widening of

interpretation of justifiable trade restrictions, the multilateral trading system is at risk

of protectionism. By default any domestic environmental regulation would take into

consideration only its own environmental/ ecological and economic interests, with complete

disregard to other countries. Yet, such local environmental considerations are neither

ecologically nor economically efficient. A WTO decision that supports specific trade

obligations pursuant to MEAs (represented by large participation of countries from

various regions and stages of development) is the only way to restrain unilateral measures

that currently threaten multilateralism.

The EC, the main demander of the environment agenda in the WTO, regards MEAs and

WTO as holding equal legal status, even though the two distinct regimes defy such ranking.

The broad agenda of the EC (supported by Switzerland and Norway), poses risk to the

multilateralism it claims to uphold, since some MEAs allow Party discretion to undertake

unilateral restrictive trade measures based on the Party s environmental priorities or

evaluation. Thus the broad agenda of EC carries a potential threat of regionalism/

unilateralism.

There is also a risk of protectionism in the definition of individual terms within the current

negotiations. While it may seem that the WTO Members have engaged in semantics of

each term contained in Paragraph 31.1 of the DMD, the final interpretation of the

provisions under the MEAs hinge on these definitions. Even supporters of the

broader agenda, like Japan, have acknowledged that the discretion provided in some

MEAs make the definition of STOs difficult, and indeed a case-by-case analysis may

be required for those MEAs. In this light, a restrictive definition of STOs as adopted by

India is a sound approach, especially to check for the protectionist pitfalls of a broader

definition.

Finally, a structured MEA-by-MEA analysis is a judicious negotiating stand to clarify the

relationship between of STOs pursuant to MEAs with WTO rules, since this would lead to

a clear understanding of what kind of trade measures for environmental purposes are

consistent under the WTO. It is important for India to work towards such a multilateral

interpretative decision and understanding within the WTO. A conceptual understanding is

20

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

particularly significant in the face of unilateral trade restrictions on environmental being

sanctified in the post-WTO era.

It is in the best interest of India to re-affirm her commitment to promoting sustainable

development along with trade liberalization, as set out in the Preamble to the WTO

Agreement and the Decision on Trade and Environment), and continue to support

environmental initiatives through MEAs. After all, the WTO is not an environmental

policy making body, and should continue to promote trade liberalization with due

respect to multilateral environmental consensus coming from organizations specializing

in those issues.

21

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

BIBLIOGRAPHY-

NEWSPAPER ARTICLES-

Sawhney, Aparna, Trade and Environment Negotiations at the WTO: The Interface of

Multilateral Environmental Governance and Multilateral Trading System, GALT Update,

The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI), New Delhi, March 2007, Nanda, Nitya,

Trade and Environment: In Search of a Global Agenda, GALT Update, TERI, March

2007.

Cheyne, Ilona, Risk and Precaution in World Trade Organization Law, Journal of World

Trade, October 2006, Vol. 40 Issue 5.

Rachel, McCormick, A Qualitative Analysis of the WTOs Role on Trade and

Environment Issues, Global Environmental Politics, February 2006, Vol. 6 Issue 1

Kirchbach, Friedrich Von, and Mimouni, Mondher An Assessment of

Environmentallyrelated Non-tariff Measures by Lionel Fontagn, World Economy,

October 2005, Vol. 28 Issue 10.

Uppal, Shaban. The WTO and Environment, Economic Review, January 2005, Vol. 36

Issue 1.

Eckersley, Robyn, The Big Chill: The WTO and Multilateral Environmental

Agreements, Global Environmental Politics, May 2004, Vol. 4 Issue 2.

BOOKS-

Environment and Trade: A Handbook, Second Edition, The United Nations Environment

Programme Division of Technology, Industry and Economics Economics and Trade Unit

and the International Institute for Sustainable Development, Canada, 2005.

Trade and environment: A resource book, ed. by Najam, Adil; Halle, Mark and Melndez-

Ortiz, Ricardo, International Center for Trade and Sustainable Development, New York,

2007.

Guru, Manjula and Rao, M.B., WTO Dispute Settlement and Developing Countries, Lexis

Nexis Butterworth, 2004.

Wardha, Harin, WTO and Third World Trade Challenges, Common Wealth, New Delhi,

2002.

Bhandari, Surendra, World Trade Organisation and Developing Countries, Deep and Deep

Publications Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, 1998.

22

World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environment

ONLINE RESOURCES-

CTE documents are found in the WTOs trade and environment official

http://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/envir_e/cte_docs_list_e.htm

Brack, D., The World Trade Organization and sustainable development: A guide to the

debate. Energy, Environment and Development Programme (EEDP), Chatham House.

London, U.K., 2005

Charnovitz, S. Exploring the Environmental Exceptions in GATT Article XX. In

Journal of World Trade 25(5),1991

Copeland, B. R. and Taylor, M.S. (2003) Trade and the Environment: Theory and

Evidence. Princeton University Press. Princeton, USA.

You might also like

- WTO Regime and Environmental ProtectionDocument15 pagesWTO Regime and Environmental Protectionprakhar chandraNo ratings yet

- University Institute of Legal Studies, Panjab University, ChandigarhDocument12 pagesUniversity Institute of Legal Studies, Panjab University, ChandigarhpoojaNo ratings yet

- Administrative Law F.DDocument16 pagesAdministrative Law F.DAyush TiwariNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law ProjectDocument21 pagesEnvironmental Law ProjectArpit GoyalNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law ProjectDocument8 pagesEnvironmental Law ProjectIzaan RizviNo ratings yet

- Indian of Legal Studies: Environmental LawDocument20 pagesIndian of Legal Studies: Environmental LawArkaprava BhowmikNo ratings yet

- Ipr2 Project PDFDocument19 pagesIpr2 Project PDFsankalp patelNo ratings yet

- Law & Agriculture FDDocument26 pagesLaw & Agriculture FDShalini SonkarNo ratings yet

- Tax ProjectDocument18 pagesTax ProjectMohammad ArishNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law ProjectDocument18 pagesEnvironmental Law ProjectBharat ChaudhryNo ratings yet

- Tax FinalDocument15 pagesTax FinalAyush AgrawalNo ratings yet

- Indirect Taxation ProjectDocument16 pagesIndirect Taxation ProjectIsha SenNo ratings yet

- Project of Admin.Document16 pagesProject of Admin.atifsjc2790No ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument18 pagesIntroductionVikas DeniaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law ProjectDocument16 pagesEnvironmental Law ProjectarunabhsharmaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law Project 2020Document19 pagesEnvironmental Law Project 2020Abhijit BansalNo ratings yet

- Project On Environmental LawDocument22 pagesProject On Environmental LawSwapnil Bhagat0% (1)

- Tax 2 ProjectDocument15 pagesTax 2 ProjectamanasheshNo ratings yet

- Environment Law ProjectDocument28 pagesEnvironment Law ProjectGauransh MishraNo ratings yet

- Environmental LAW Project-DevvratDocument22 pagesEnvironmental LAW Project-DevvratdhawalNo ratings yet

- Research Paper On International Environmental Law - ShivikaDocument28 pagesResearch Paper On International Environmental Law - ShivikaAnanyaSinghalNo ratings yet

- Labour Law Final DraftDocument19 pagesLabour Law Final Drafts. k. VyasNo ratings yet

- Role of IPR in Indian Pharma & Generics in IndiaDocument34 pagesRole of IPR in Indian Pharma & Generics in IndiaDenny AlexanderNo ratings yet

- International environmental laws on persistent organic pollutantsDocument21 pagesInternational environmental laws on persistent organic pollutantsSiddhant MathurNo ratings yet

- Calculation of Rent: A StudyDocument12 pagesCalculation of Rent: A StudyMamta BishtNo ratings yet

- Taxation Law ProjectDocument20 pagesTaxation Law ProjectJain Rajat ChopraNo ratings yet

- Labour LawDocument23 pagesLabour LawAbhisht HelaNo ratings yet

- TRADE AND ENVIRONMENT PROJECT REPORTDocument19 pagesTRADE AND ENVIRONMENT PROJECT REPORTApoorvaChandraNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law ProjectDocument26 pagesEnvironmental Law ProjectAparna SinghNo ratings yet

- Taxation of Income from Other SourcesDocument33 pagesTaxation of Income from Other SourcesAyush PandeyNo ratings yet

- Health & Medicine Law Final DraftDocument12 pagesHealth & Medicine Law Final DraftDeepak RavNo ratings yet

- Jurisprudence II ProjectDocument17 pagesJurisprudence II ProjectVishwaja RaoNo ratings yet

- Korean Soju DisputeDocument20 pagesKorean Soju Disputekrishna6941100% (1)

- ADR Term Paper CompletedDocument26 pagesADR Term Paper CompletedJorden SherpaNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law ProjectDocument10 pagesEnvironmental Law ProjectSuvedhya ReddyNo ratings yet

- Are Bailouts a Subsidy Under WTO RulesDocument21 pagesAre Bailouts a Subsidy Under WTO RulesVaibhav GuptaNo ratings yet

- PDF Intellectual Property Rights Assignment Session 2016 17 Analysis of Designs Act 2000Document9 pagesPDF Intellectual Property Rights Assignment Session 2016 17 Analysis of Designs Act 2000WanteiNo ratings yet

- NLIU Bhopal Delegated Legislation StudyDocument30 pagesNLIU Bhopal Delegated Legislation StudyAnamika SinghNo ratings yet

- Labour Law II ProjectDocument13 pagesLabour Law II ProjectSwapna SinghNo ratings yet

- Ashu Env LawDocument18 pagesAshu Env LawAshutosh BiswasNo ratings yet

- A Project Report Submitted To: Ms. Priyanka Ghai Subject: Professional EthicsDocument20 pagesA Project Report Submitted To: Ms. Priyanka Ghai Subject: Professional EthicsAnirudh VermaNo ratings yet

- ILO Convention 182 protects children from hazardous workDocument21 pagesILO Convention 182 protects children from hazardous workAnkit GargNo ratings yet

- Air & Space Law (2017BALLB110)Document18 pagesAir & Space Law (2017BALLB110)ankitNo ratings yet

- Labour Law 2 Final ProjectDocument19 pagesLabour Law 2 Final ProjectKumar MangalamNo ratings yet

- Environmental LawDocument24 pagesEnvironmental LawAyushiDwivediNo ratings yet

- Conservation of Bio-Diversity in IndiaDocument31 pagesConservation of Bio-Diversity in IndiaAmulya KaushikNo ratings yet

- Labour ProjectDocument26 pagesLabour ProjectAbhigyat ChaitanyaNo ratings yet

- Neelam Rathore CRIDocument14 pagesNeelam Rathore CRIAlok RathoreNo ratings yet

- Egal Onundrum OF THE HE Right TO Fair Compensation AND Transparency IN Land Acquisition Rehabilitation AND Resettlement ACT Ritical PpraisalDocument10 pagesEgal Onundrum OF THE HE Right TO Fair Compensation AND Transparency IN Land Acquisition Rehabilitation AND Resettlement ACT Ritical PpraisalUtkarsh KhandelwalNo ratings yet

- Farmers Agitation and Farm Law 2020: Critical Study: SociologyDocument5 pagesFarmers Agitation and Farm Law 2020: Critical Study: SociologySonu SangamNo ratings yet

- Dr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University Lucknow: Project OnDocument14 pagesDr. Ram Manohar Lohiya National Law University Lucknow: Project OndivyavishalNo ratings yet

- Law and Agriculture ProjectDocument12 pagesLaw and Agriculture ProjectMeghna SinghNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Critical Issues Under the SARFAESI Act, 2002Document22 pagesAnalysis of Critical Issues Under the SARFAESI Act, 2002Anchal SinghNo ratings yet

- Competition Law: Banking & Financial Institutions & Environmental SafeguardsDocument15 pagesCompetition Law: Banking & Financial Institutions & Environmental SafeguardsAshish SinghNo ratings yet

- Subject: Labour Law: Chanakya National Law University, PatnaDocument11 pagesSubject: Labour Law: Chanakya National Law University, PatnaAJIT SHARMANo ratings yet

- Environmental Law RadhaDocument13 pagesEnvironmental Law RadharadhakrishnaNo ratings yet

- Labour Law ProjectDocument31 pagesLabour Law Projectasha sreedharNo ratings yet

- Environment Project Sem6Document15 pagesEnvironment Project Sem6Amit RawlaniNo ratings yet

- Fundamental Rights ExpandedDocument13 pagesFundamental Rights ExpandedRishabh Narain SinghNo ratings yet

- A Project Report ON World Trade Organisation and Protection of EnvironmentDocument22 pagesA Project Report ON World Trade Organisation and Protection of Environmentlokesh chandra ranjanNo ratings yet

- Areas of PracticeDocument6 pagesAreas of PracticePalash JainNo ratings yet

- Corporate Finance Is An Area of Finance Dealing With The Financial Decisions Corporations Make and The Tools and Analysis Used To Make These DecisionsDocument21 pagesCorporate Finance Is An Area of Finance Dealing With The Financial Decisions Corporations Make and The Tools and Analysis Used To Make These DecisionsPalash JainNo ratings yet

- E Commerce Laws in IndiaDocument19 pagesE Commerce Laws in IndiaPriya ZutshiNo ratings yet

- Abolition or Retention of the Death Penalty in India: A Critical ReappraisalDocument16 pagesAbolition or Retention of the Death Penalty in India: A Critical ReappraisalPalash JainNo ratings yet

- Investor Protection and Corporate Governance Dissertation For Seminar Paper I 1Document58 pagesInvestor Protection and Corporate Governance Dissertation For Seminar Paper I 1Palash JainNo ratings yet

- 5 ApproachesDocument15 pages5 ApproachesPalash JainNo ratings yet

- 5 ApproachesDocument15 pages5 ApproachesPalash JainNo ratings yet

- 5 ApproachesDocument15 pages5 ApproachesPalash JainNo ratings yet

- India's Travails with the Death PenaltyDocument30 pagesIndia's Travails with the Death PenaltyPalash JainNo ratings yet

- Justice Verma ReportDocument657 pagesJustice Verma ReportBar & Bench75% (4)

- BG PaperDocument4 pagesBG PaperPalash JainNo ratings yet

- Justice Verma ReportDocument657 pagesJustice Verma ReportBar & Bench75% (4)

- HTTP - WWW - Aphref.aph - Gov.au House Committee Laca Copyrightenforcement Chap5 PDFDocument18 pagesHTTP - WWW - Aphref.aph - Gov.au House Committee Laca Copyrightenforcement Chap5 PDFJainPalashNo ratings yet

- Early Criminology Theories and Modern CounterpartsDocument34 pagesEarly Criminology Theories and Modern CounterpartsghazalatabassumNo ratings yet

- Sem 5 TaxDocument22 pagesSem 5 TaxPalash JainNo ratings yet

- Abolition or Retention of the Death Penalty in India: A Critical ReappraisalDocument16 pagesAbolition or Retention of the Death Penalty in India: A Critical ReappraisalPalash JainNo ratings yet

- HiDocument34 pagesHiPalash JainNo ratings yet

- ADR Syllabus VIDocument3 pagesADR Syllabus VIPalash JainNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesCorporate Social ResponsibilityPalash JainNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument27 pagesIntroductionPalash JainNo ratings yet

- Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument16 pagesCorporate Social ResponsibilityPalash JainNo ratings yet

- 10 Chapgkgkter 4Document50 pages10 Chapgkgkter 4Palash JainNo ratings yet

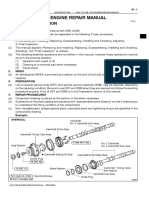

- How To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationDocument3 pagesHow To Use This Engine Repair Manual: General InformationHenry SilvaNo ratings yet

- Tata Hexa (2017-2019) Mileage (14 KML) - Hexa (2017-2019) Diesel Mileage - CarWaleDocument1 pageTata Hexa (2017-2019) Mileage (14 KML) - Hexa (2017-2019) Diesel Mileage - CarWaleMahajan VickyNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Conflicts and PeacekeepingDocument2 pagesEthnic Conflicts and PeacekeepingAmna KhanNo ratings yet

- As If/as Though/like: As If As Though Looks Sounds Feels As If As If As If As Though As Though Like LikeDocument23 pagesAs If/as Though/like: As If As Though Looks Sounds Feels As If As If As If As Though As Though Like Likemyint phyoNo ratings yet

- Housekeeping NC II ModuleDocument77 pagesHousekeeping NC II ModuleJoanne TolopiaNo ratings yet

- Topic 4: Mental AccountingDocument13 pagesTopic 4: Mental AccountingHimanshi AryaNo ratings yet

- University of Wisconsin Proposal TemplateDocument5 pagesUniversity of Wisconsin Proposal TemplateLuke TilleyNo ratings yet

- Wonder at The Edge of The WorldDocument3 pagesWonder at The Edge of The WorldLittle, Brown Books for Young Readers0% (1)

- Device Exp 2 Student ManualDocument4 pagesDevice Exp 2 Student Manualgg ezNo ratings yet

- 1120 Assessment 1A - Self-Assessment and Life GoalDocument3 pages1120 Assessment 1A - Self-Assessment and Life GoalLia LeNo ratings yet

- 2C Syllable Division: Candid Can/dDocument32 pages2C Syllable Division: Candid Can/dRawats002No ratings yet

- Political Philosophy and Political Science: Complex RelationshipsDocument15 pagesPolitical Philosophy and Political Science: Complex RelationshipsVane ValienteNo ratings yet

- FPR 10 1.lectDocument638 pagesFPR 10 1.lectshishuNo ratings yet

- The Insanity DefenseDocument3 pagesThe Insanity DefenseDr. Celeste Fabrie100% (2)

- Ethiopian Civil Service University UmmpDocument76 pagesEthiopian Civil Service University UmmpsemabayNo ratings yet

- Data FinalDocument4 pagesData FinalDmitry BolgarinNo ratings yet

- CSR of Cadbury LTDDocument10 pagesCSR of Cadbury LTDKinjal BhanushaliNo ratings yet

- 14 Jet Mykles - Heaven Sent 5 - GenesisDocument124 pages14 Jet Mykles - Heaven Sent 5 - Genesiskeikey2050% (2)

- Italy VISA Annex 9 Application Form Gennaio 2016 FinaleDocument11 pagesItaly VISA Annex 9 Application Form Gennaio 2016 Finalesumit.raj.iiit5613No ratings yet

- Supply Chain AssignmentDocument29 pagesSupply Chain AssignmentHisham JackNo ratings yet

- (Template) Grade 6 Science InvestigationDocument6 pages(Template) Grade 6 Science InvestigationYounis AhmedNo ratings yet

- MM-18 - Bilge Separator - OPERATION MANUALDocument24 pagesMM-18 - Bilge Separator - OPERATION MANUALKyaw Swar Latt100% (2)

- R19 MPMC Lab Manual SVEC-Revanth-III-IIDocument135 pagesR19 MPMC Lab Manual SVEC-Revanth-III-IIDarshan BysaniNo ratings yet

- GCSE Ratio ExercisesDocument2 pagesGCSE Ratio ExercisesCarlos l99l7671No ratings yet

- DRRR STEM 1st Quarter S.Y.2021-2022Document41 pagesDRRR STEM 1st Quarter S.Y.2021-2022Marvin MoreteNo ratings yet

- Maternity and Newborn MedicationsDocument38 pagesMaternity and Newborn MedicationsJaypee Fabros EdraNo ratings yet

- Solidworks Inspection Data SheetDocument3 pagesSolidworks Inspection Data SheetTeguh Iman RamadhanNo ratings yet

- 05 Gregor and The Code of ClawDocument621 pages05 Gregor and The Code of ClawFaye Alonzo100% (7)

- The Serpents Tail A Brief History of KHMDocument294 pagesThe Serpents Tail A Brief History of KHMWill ConquerNo ratings yet

- The Wild PartyDocument3 pagesThe Wild PartyMeganMcArthurNo ratings yet