Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Habib Agrarian System Libre

Uploaded by

alisyed37Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Habib Agrarian System Libre

Uploaded by

alisyed37Copyright:

Available Formats

1

Irfan Habib, The Agrarian System of Mughal India, 1556-1707, Second Revised

Edition (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 1999), pp. xvi+547, Rs. 545/-.

When the first edition of the book under review appeared in 1963, it was a historic event

for Mughal studies. It has been out of print and a new edition was long overdue, revised

or otherwise. It was one of the first works to have moved beyond the narrow confines of

dynastic history or sectarian typecasting. Satish Chandras Parties and Politics at the

Mughal Court preceded Habibs monograph by four years. However, Chandras work

concerned itself exclusively with the later phase of the Mughal period whereas Habib set

for himself a more ambitious agenda. The strength of Habibs seminal work lay in its

attempt to look into the entire agrarian system through an investigation of Mughal land

revenue administration, agrarian economy and social structure spanning the period from

1556 to 1707. The wealth of source materials, particularly administrative manuals,

revenue records and court chronicles that went into the making of the text, helped enforce

a new rigour into medieval Indian studies. Indeed, it set the tone for much of the writing

in the field for the next twenty-five years or so.

Much water and blood has flowed through Mughal historiography since. Particularly

contested are Habibs ideas of extreme centralization of power in the hands of an

absolutist monarch, the self-sufficiency of the village economy and the agrarian crisis of

the eighteenth century. However, Habib does not take note of these challenges in this

revised edition. If anything, he is even more assertive in his conclusions. This is

unfortunate. For, the inspiring force of The Agrarian System was not just its wealth of

information but also the tentative tenor of the authors formulations. The contradictions

in the revised edition stand more exposed than in the original.

To be sure, a number of new sources have been harnessed in this edition. While the

sequence and titles of the chapters remain the same, the chapter on the village community

has been modified and enlarged considerably. A more nuanced view of the village

community has been attempted but over all this does not alter the chief arguments of the

2

book. However, the author fails to do justice to the variety of information that he has

collected. Thus, his conclusion that the unity and cohesion of the Mughal ruling class

found its practical expression in the absolute power of the emperor (p. 366) cannot be

reconciled with his own admission that the imperial regulationsleft a considerable

field of discretion to the jagirdars (p. 369). In the same context, he even concedes that

the regulations themselves could also be simply violated or evaded in practice (p.

369). If the jagirdars defied the imperial authority with impunity, the local chiefs were

free to levy cesses and duties on trade passing through their territories at rates fixed by

themselves. Their methods of revenue administration did not necessarily follow the

regulations laid down by the imperial government (p. 225). Again this cannot simply be

dismissed especially when one considers that the extent of the territory ruled by chiefs

and princelings was not by any means negligible (p. 229). This is an astonishing hole in

his argument because the whole idea of the centralization of power rests on the

hypothesis that the mansabdars were completely dependent on the will of the

emperor(p. 366) and that the local potentates could be controlled. The material basis of

the states enormous strength apparently derived from its ability to skim off the entire

agrarian surplus. Yet, the author is keen on maintaining that the land revenue was a

retrogressive tax (pp. 136 and 232). This is a clearly irreconcilable stand to take unless

one is prepared to define surplus very differently for the different rural classes. If

surplus is taken to mean, as Habib does, everything beyond the subsistence need of the

peasants, then the revenue regime must be progressive enough to be able to take away the

entire agrarian surplus. For, the rich will have much more to spare than the poor.

Similarly, the evidence about a piece of cultivated land being sold[by]two

individual peasants (p. 151) does not stop him from observing elsewhere that the peasant

was a semi-serf, not a free agent. And his right, such as it was, was seldom saleable (p.

134). Part of the problem in the text emerges from the authors indiscriminate use of

evidences, culled from sources far removed from each other in time, space and genre.

This is followed by an attempt to weave through an all India pattern for the entire length

of the period from mid sixteenth century to early eighteenth century. His obsession with

all India pattern probably emanates from an a priori assumption that the state and its

3

regulations must be the chief determinant of all aspects of social, economic and political

life under the Mughals. Thus, even while reasserting in the preface to the new edition that

the Agrarian System in the title should be understood to encompass not only land

revenue administration, but also agrarian economy and social structure, he is prompt in

emphasizing that the central feature of the agrarian system of Mughal India was that the

transfer from the peasant of his surplus producewas largely by way of exaction of land

revenue (p. 230).

Reading through the revised edition, one is almost led to believe that the Mughal

historiography today is no richer in terms of multiplicity of perspectives. It appears that

all the writings that did appear in the last four decades only helped him march gracefully

and unopposed to his grand set of conclusions. To be sure, he does take on Moreland at

many places and there are minor expostulations against Moosvi and Saran but no sense of

wading through a thickly contested historiographic terrain.

Yet, no student of medieval Indian history can probably afford to ignore this classic.

With passage of time and progress of historiography, it might have come to represent the

orthodox perspective, but it continues to be extremely useful, in relation to which

students of Mughal studies would continue to shape their own ideas for a long time to

come.

Pankaj K.Jha

St. Stephens College

University of Delhi

You might also like

- Notes On Symbolic LogicDocument12 pagesNotes On Symbolic Logicalisyed37No ratings yet

- The Riyazu-S-Sulatin A History of BengalDocument467 pagesThe Riyazu-S-Sulatin A History of BengalSwarnendu Chakraborty100% (1)

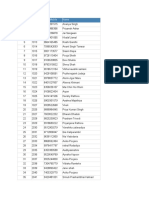

- SR User ID User Mobile NameDocument50 pagesSR User ID User Mobile NameytrdfghjjhgfdxcfghNo ratings yet

- Iqbal S Conception of Muslim NationalismDocument18 pagesIqbal S Conception of Muslim Nationalismalisyed37No ratings yet

- Weber Ideal TypesDocument4 pagesWeber Ideal Typesalisyed37No ratings yet

- Avendus Specialty Chemicals ReportDocument112 pagesAvendus Specialty Chemicals Reportsiddharth_parikh4No ratings yet

- Method Vs MethodologyDocument6 pagesMethod Vs Methodologyalisyed37No ratings yet

- Outlines of Formal LogicDocument282 pagesOutlines of Formal Logicalisyed37100% (1)

- 7Document91 pages7Arnav JoshiNo ratings yet

- Did Aurangzeb Ban MusicDocument45 pagesDid Aurangzeb Ban MusicUwais Namazi0% (1)

- Mobilization Advance LetterDocument2 pagesMobilization Advance Letterksrao67% (9)

- Provisional Electoral Roll 2017Document354 pagesProvisional Electoral Roll 2017Aarti33% (3)

- Itcs-Ch 1Document21 pagesItcs-Ch 1The One100% (1)

- State and Society in Medieval IndiaDocument8 pagesState and Society in Medieval IndiaAiswaryaNo ratings yet

- THE MUGHAL EMPIRE (1526-1707) : The Mughal Emperors (First Six Rulers) - BABUR (1526-30) HUMAYUN (1530-56)Document66 pagesTHE MUGHAL EMPIRE (1526-1707) : The Mughal Emperors (First Six Rulers) - BABUR (1526-30) HUMAYUN (1530-56)Ajay DevasiaNo ratings yet

- Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya - Representing The Other - Sanskrit Sources and The Muslims (8th-14th Century) - Manohar Publishers and Distributors (1998) PDFDocument63 pagesBrajadulal Chattopadhyaya - Representing The Other - Sanskrit Sources and The Muslims (8th-14th Century) - Manohar Publishers and Distributors (1998) PDFneetuNo ratings yet

- Rebels, Mystics or Housewives Women in Virasaivism - Vijaya RamaswamyDocument15 pagesRebels, Mystics or Housewives Women in Virasaivism - Vijaya RamaswamyStanzin PhantokNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of SocietyDocument11 pagesCharacteristics of Societyalisyed37No ratings yet

- 18th Century CrisisDocument6 pages18th Century CrisisMaryam KhanNo ratings yet

- 07 Introduction PDFDocument12 pages07 Introduction PDFnazmul100% (1)

- Ain e Akbari AssignmentDocument10 pagesAin e Akbari AssignmentAnaya Anzail Khan100% (1)

- 2 - Integration of Indigenous GroupsDocument7 pages2 - Integration of Indigenous GroupsUtsav KumarNo ratings yet

- Indian Feudalism DebateDocument16 pagesIndian Feudalism DebateJintu ThresiaNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Vernacular LangauagesDocument43 pagesEvolution of Vernacular LangauagesShakuntala PetwalNo ratings yet

- State, Power and Legitimacy:The Gupta DynastyDocument6 pagesState, Power and Legitimacy:The Gupta DynastyAnonymous G6wToMENo ratings yet

- 7 Rise and Growth ofDocument11 pages7 Rise and Growth ofShiv Shankar ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Using Max Weber Concept of Social Action and Emile Durkheim Concept of The Social Fact. Write A Commentary On The Uniqeness of Sociological WorkDocument4 pagesUsing Max Weber Concept of Social Action and Emile Durkheim Concept of The Social Fact. Write A Commentary On The Uniqeness of Sociological Workkunal mehtoNo ratings yet

- Labour During Mughal India - Rosalind O HanlonDocument36 pagesLabour During Mughal India - Rosalind O HanlonArya MishraNo ratings yet

- Sources For Rural Society of Medieval IndiaDocument8 pagesSources For Rural Society of Medieval IndiaNeha AnandNo ratings yet

- Anupam TripathiDocument8 pagesAnupam TripathiAnupamNo ratings yet

- Social Dimensions of Art in Early IndiaDocument31 pagesSocial Dimensions of Art in Early IndiaPriyanka Mokkapati100% (1)

- Anglo MysoreDocument26 pagesAnglo Mysoreannarosedavis annarosedavisNo ratings yet

- Evolution of Political Structures North IndiaDocument15 pagesEvolution of Political Structures North IndiaLallan SinghNo ratings yet

- History of AzamgarhDocument3 pagesHistory of AzamgarhkhurshidazmiNo ratings yet

- Creation of New Political Culture in French RevolutionDocument4 pagesCreation of New Political Culture in French RevolutionDhruv Aryan Kundra100% (1)

- Indian Pre History: North India: (Also Known As Sohan Culture)Document14 pagesIndian Pre History: North India: (Also Known As Sohan Culture)Manish YadavNo ratings yet

- Different Schools of Thought #SPECTRUMDocument8 pagesDifferent Schools of Thought #SPECTRUMAditya ChourasiyaNo ratings yet

- Kushana PolityDocument5 pagesKushana PolityKunalNo ratings yet

- History of India (University of Delhi) History of India (University of Delhi)Document5 pagesHistory of India (University of Delhi) History of India (University of Delhi)Coolgirl AyeshaNo ratings yet

- ChachaDocument15 pagesChachaGopniya PremiNo ratings yet

- History Optional Notes: Delhi SultanateDocument89 pagesHistory Optional Notes: Delhi SultanateHarshNo ratings yet

- Religion and Society in Medieval IndiaDocument8 pagesReligion and Society in Medieval Indiasreya guha100% (1)

- China's Path To Modernization NotesDocument30 pagesChina's Path To Modernization NotesAlicia Helena Cheang50% (2)

- Imperialism, Porter Andrew, European 1860 1914Document133 pagesImperialism, Porter Andrew, European 1860 1914Anushree DeyNo ratings yet

- Mughal War of SuccessionDocument9 pagesMughal War of SuccessionSimran RaghuvanshiNo ratings yet

- Popular Rights Movement in JapanDocument6 pagesPopular Rights Movement in JapanJikmik MoliaNo ratings yet

- MouryasDocument73 pagesMouryasSattibabu ChelluNo ratings yet

- Popular Magazines in KeralaDocument11 pagesPopular Magazines in Keralababithamarina100% (1)

- Gender Relationships in The Mahabharata PDFDocument38 pagesGender Relationships in The Mahabharata PDFDiptesh SahaNo ratings yet

- William Jone and The OrientDocument18 pagesWilliam Jone and The OrientTalaat FarouqNo ratings yet

- Expansion of Mughal Empire From Akbar To AurangzebDocument4 pagesExpansion of Mughal Empire From Akbar To AurangzebEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Early Medieval IndiaDocument19 pagesEarly Medieval IndiaIndianhoshi HoshiNo ratings yet

- Sonal Singh - Grant of DiwaniDocument12 pagesSonal Singh - Grant of DiwaniZoya NawshadNo ratings yet

- Role of Chiang Kai Shek and The Kuomintang Shreya Raulo Final Sf0118050 Semster 3 History ProjectDocument16 pagesRole of Chiang Kai Shek and The Kuomintang Shreya Raulo Final Sf0118050 Semster 3 History ProjectShreya Raulo100% (1)

- Asaf Khan Vis-A-Vis Nur Jahan's Junta (1611-1621)Document16 pagesAsaf Khan Vis-A-Vis Nur Jahan's Junta (1611-1621)Zubair Ah RatherNo ratings yet

- Block 5Document104 pagesBlock 5Rishali Chauhan 84No ratings yet

- AurangzebDocument3 pagesAurangzebnmahmud750% (1)

- A Study of Persian Literature Under The Mughals in IndiaDocument5 pagesA Study of Persian Literature Under The Mughals in IndiapoocNo ratings yet

- Indian Merchants and The Western Indian Ocean - The Early Seventeenth CenturyDocument20 pagesIndian Merchants and The Western Indian Ocean - The Early Seventeenth CenturyKpatowary90No ratings yet

- Panjab University, Chandigarh: (Established Under The Panjab University Act VII of 1947-Enacted by The Govt. of India)Document74 pagesPanjab University, Chandigarh: (Established Under The Panjab University Act VII of 1947-Enacted by The Govt. of India)Gurman PattoNo ratings yet

- BaraniDocument64 pagesBaraniSheikh Bilal Farooq100% (1)

- A Critical Survey of The MahabhartaDocument2 pagesA Critical Survey of The MahabhartainventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Gautamiputra Satkarn-ShravanDocument2 pagesGautamiputra Satkarn-ShravanPinapati VikranthNo ratings yet

- Mrigavati by Shakya Qutban SuhrawardiDocument2 pagesMrigavati by Shakya Qutban SuhrawardiEshaa JainNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document40 pagesChapter 2luciferNo ratings yet

- Smartprep - In: Mauryan Empire - Socio-Economic, Political and Religious ConditionsDocument34 pagesSmartprep - In: Mauryan Empire - Socio-Economic, Political and Religious ConditionsKriti Singh100% (1)

- Institute of Architecture H.N.G.U - Patan: By:-Shreya Rastogi Deesha Khamar Parv Dhonde Ishan JainDocument17 pagesInstitute of Architecture H.N.G.U - Patan: By:-Shreya Rastogi Deesha Khamar Parv Dhonde Ishan JainishanNo ratings yet

- Sangam Period - Literature, Administration and Economic ConditionDocument23 pagesSangam Period - Literature, Administration and Economic Conditionavinash_formalNo ratings yet

- Muhammad Ali Qureshi and Hasan Raza: NamesDocument16 pagesMuhammad Ali Qureshi and Hasan Raza: NamesTanishq MalhotraNo ratings yet

- Communla Attitude To British Policy Partition of Bengal CaseDocument14 pagesCommunla Attitude To British Policy Partition of Bengal Casealisyed37No ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Partition of BengalDocument23 pagesA Critical Analysis of Partition of Bengalalisyed37No ratings yet

- Partition of Bengal PDFDocument3 pagesPartition of Bengal PDFAli Rizwan0% (1)

- 2 Bengal Partition 1905 British NewspapersDocument247 pages2 Bengal Partition 1905 British Newspapersrajarshi raghuvanshiNo ratings yet

- A Critical Analysis of Partition of BengalDocument23 pagesA Critical Analysis of Partition of Bengalalisyed37No ratings yet

- Communla Attitude To British Policy Partition of Bengal CaseDocument14 pagesCommunla Attitude To British Policy Partition of Bengal Casealisyed37No ratings yet

- Informal FallaciesDocument15 pagesInformal Fallaciesalisyed37No ratings yet

- Husain Ahmad Madani Views On Composite NationalismDocument8 pagesHusain Ahmad Madani Views On Composite Nationalismalisyed3750% (2)

- Sikh Religious InstituionsDocument56 pagesSikh Religious Instituionsalisyed37No ratings yet

- (P. D. Magnus) Forall X An Introduction To Formal (B-Ok - CC)Document113 pages(P. D. Magnus) Forall X An Introduction To Formal (B-Ok - CC)alisyed37No ratings yet

- Iqbal Aur MullahDocument31 pagesIqbal Aur MullahMatthew WaltersNo ratings yet

- Source: Census, Punjab Report 1911. Vol. XIV Part I, 14Document5 pagesSource: Census, Punjab Report 1911. Vol. XIV Part I, 14alisyed37No ratings yet

- Vol 10 Winter 12 - Complete PDFDocument69 pagesVol 10 Winter 12 - Complete PDFalisyed37No ratings yet

- Chapter-1 Proto-History Refers To A Period Between Pre-History and History. It Is GenerallyDocument12 pagesChapter-1 Proto-History Refers To A Period Between Pre-History and History. It Is Generallyalisyed37No ratings yet

- Pakistan Regional AppratusDocument22 pagesPakistan Regional Appratusalisyed37No ratings yet

- A Brief History of POLITICAL Evoution of PakistanDocument11 pagesA Brief History of POLITICAL Evoution of Pakistanalisyed37No ratings yet

- CIVIL Miltary RelationsDocument26 pagesCIVIL Miltary Relationsalisyed37No ratings yet

- Source: Census, Punjab Report 1911. Vol. XIV Part I, 14Document5 pagesSource: Census, Punjab Report 1911. Vol. XIV Part I, 14alisyed37No ratings yet

- Rare Document About Organizing of Punjab Unionist PartyDocument1 pageRare Document About Organizing of Punjab Unionist Partyalisyed37No ratings yet

- W James On Role of IndividualDocument5 pagesW James On Role of Individualalisyed37No ratings yet

- Proxy Wars in PakistanDocument2 pagesProxy Wars in Pakistanalisyed37No ratings yet

- Venn Diagram For Plurative LogicDocument8 pagesVenn Diagram For Plurative Logicalisyed37No ratings yet

- Lecture Notes On Logical Reasoning ConceDocument45 pagesLecture Notes On Logical Reasoning Concealisyed37No ratings yet

- Five Modes of Social InquiryDocument2 pagesFive Modes of Social Inquiryalisyed37100% (1)

- Eng - Cultural Heritage of IndiaDocument181 pagesEng - Cultural Heritage of IndiaMy study BommapalaNo ratings yet

- Demographic Trends in IndiaDocument6 pagesDemographic Trends in IndiaKrishnaveni MurugeshNo ratings yet

- Project Report On KapecDocument84 pagesProject Report On KapecBasant SinghNo ratings yet

- Form of Certificate Prescribed For Scheduled Caste or Scheduled TribeDocument2 pagesForm of Certificate Prescribed For Scheduled Caste or Scheduled TribeanilplpNo ratings yet

- 2 Dead in Fresh Targeted Killings in Valley: No Language Is Less Than Hindi, English'Document15 pages2 Dead in Fresh Targeted Killings in Valley: No Language Is Less Than Hindi, English'SPNo ratings yet

- A Study On Brand Preference of Baby Foods With Special Reference To Semi Solid FoodsDocument40 pagesA Study On Brand Preference of Baby Foods With Special Reference To Semi Solid FoodskalaivaniNo ratings yet

- List of Candidates Provisionally Selected For The Post of Probationary ClerkDocument5 pagesList of Candidates Provisionally Selected For The Post of Probationary ClerkAkash MishraNo ratings yet

- Bed - Special Education-Approved InstitutesDocument67 pagesBed - Special Education-Approved InstitutesnileshmsawantNo ratings yet

- An Assignment On Textbook Analysis - 095311Document9 pagesAn Assignment On Textbook Analysis - 095311Kiran GhoshNo ratings yet

- Pisa Eligible - KV Iit PowaiDocument15 pagesPisa Eligible - KV Iit PowaiAshutosh VaidyaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Sa GenDocument28 pages2021 Sa GenRohan JagadeesNo ratings yet

- Kendriya Vidyalaya RWF, Yelahanka, Bangalore 05.05.2022 Selection List-1 of Candidates For Class I Admission For The Session 2022-23Document2 pagesKendriya Vidyalaya RWF, Yelahanka, Bangalore 05.05.2022 Selection List-1 of Candidates For Class I Admission For The Session 2022-23jai_sharma1988No ratings yet

- Welcome To IBPS - (CWE - Clerks-IV) - Application Form PrintDocument1 pageWelcome To IBPS - (CWE - Clerks-IV) - Application Form Printrickyali_rocksNo ratings yet

- List of 570 Indian Journals Indexed in Scopus DatabaseDocument22 pagesList of 570 Indian Journals Indexed in Scopus DatabaseManoranjan Das42% (19)

- EY Making Experiences in IndiaDocument60 pagesEY Making Experiences in Indiasanjeev_bsgNo ratings yet

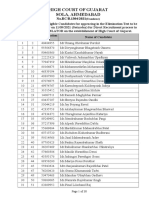

- High Court of Gujarat Sola, Ahmedabad: No - RC/B.1304/2021Document30 pagesHigh Court of Gujarat Sola, Ahmedabad: No - RC/B.1304/2021Sweet PatelNo ratings yet

- Ancient India & Medieval India, Indian Art, Heritage & Indian CultureDocument2 pagesAncient India & Medieval India, Indian Art, Heritage & Indian CultureOfey PVNo ratings yet

- It's Not Business As Usual: Startups in Healthcare, Education, LivelihoodDocument42 pagesIt's Not Business As Usual: Startups in Healthcare, Education, Livelihoodmeghnarao91No ratings yet

- BlueplastfinDocument154 pagesBlueplastfinsumeet dasNo ratings yet

- Legal Method Research Paper PDFDocument15 pagesLegal Method Research Paper PDFchirkankshit bulaniNo ratings yet

- Zee TelefilmsDocument16 pagesZee TelefilmsSwastika Akhowri100% (2)

- Tahqeeq Murqqa-e-DehliDocument11 pagesTahqeeq Murqqa-e-DehliMuhammad JunaidNo ratings yet

- Insurance CompaniesDocument5 pagesInsurance CompaniesRajesh GawdeNo ratings yet

- The Crisis of Hinduism (A. K. Saran) PDFDocument14 pagesThe Crisis of Hinduism (A. K. Saran) PDFIsraelNo ratings yet

- The Gandhi - Jinnah Talks - Umer RazzakDocument13 pagesThe Gandhi - Jinnah Talks - Umer RazzakUmer RazzakNo ratings yet