Professional Documents

Culture Documents

EN

Uploaded by

reacharunkOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

EN

Uploaded by

reacharunkCopyright:

Available Formats

<)08

PRACTICK

OF A RCHITKCTUIIE.

Book III.

bitants only, possessing in fact no more beauty than we now

jrive to a back staircase. Tliey

are for tlic most part dark, narrow, and

inconvenient. Even in Italy, which in tlie splen-

dour of its buildings

preceded and surpassed all the other nations of Europe, the staircase

was, till a late period,

extremely simple in the largest and grandest palaces. Such are the

staircases of the Vatican,

Bernini's celebrated one being comparatively of a late date. The

old staircases of the

Tuilleries and of the Louvre, though on a considerable scale, are, from

their simplicity,

construction,

and situation, little in unison with the richness of the rest

of these palaces. And this was the

consequence of having the state apartments on tiie

ground floor.

When they were removed to a higher place, the staircase which conducted

to them

necessarily led to a correspondence

of design in it.

2802. It will be observed that our observations in this section are confined to internal

staircases.

Lar<Te flights of steps, such as those at the Trinita de" Monti and AraceH at

Rome, do not come within our notice, being unrestricted in their extent, and scarcely

subject to the general laws of architectural composition. In these it should however be

remembered that they must never rise in a continued series of steps from the bottom to the

summit, but must be provided with landings for resting places, as is usually the case in the

iialf and quarter spaces of internal stairs. An extremely fine example of an external flight of

stairs may be cited in those descending from the terrace to the orangery at Versailles. For

simplicity, grandeur, design, and beauty of construction, we scarcely know anything in

Europe more admirable than this staircase and the orangery to which it leads.

2803. The selection of the place in which the staircase of a dwelling is to be seated,

requires great judgment, and is always a difficult task in the form.ation of a plan. Palladio,

I lie great master of the moderns, thus delivers the rules for observance in planning them,

that they may not be an obstruction to the rest of the buildmg. He says,

"

A particular

place must be marked out, that no part of the building should receive any prejudice by

them. There are three openings necessary to a staircase. The first is the doorway that

leads to it, which the more it is in sight the better it is ;

and 1 highly approve of its

being in such a place that before one comes to it the best part of the house may be seen,

for although the house be small, yet by such arrangement it will appear larger: the door,

however, must be obvious, and easy to be found. The second opening is tliat of the win-

dows through which the stairs are lighted

;

they should be in the middle, and large

enough to light the stairs in every part. The third opening is the landing place by which

one enters into the rooms above

;

it ought to be fair and well ornamented, and to lead

into the largest places first."

2804.

"

Staircases," continues our author,

"

will be perfect, if they are spacious, light,

and easy to ascend ;

as if, indeed, they seemed to invite people to mount. They will be

clear, if the light is bright and equally diflTused ;

and they will be suflKciently ample, if they

do not appear scanty and narrow in proportion to the size and quality of the building.

Nevertheless, they ought never to be narrower than 4 feet "(4 feet 6 inches English *),

"so

that two i)ersons meeting on the stairs may conveniently pass each other. They will be

convenient with respect to the whole building, if the arches under them can be used for

domestic purjjoses ; and commodious for the persons going up and down, if the stairs are

not too steep nor the steps too high. Therefore, they must be twice as long as broad.

The steps ought not to exceed 6 inches in height ; and if they be lower they must be so to

long and continued stairs, for they will be so much the easier, because one needs not lift

the foot so high

;

but tliey must never be lower than 4 inches." (Tliese are Vicentine

inches.

)

"

The breadth of the steps ought not to be less than a foot, nor more than a foot

and a half. The ancients used to make the steps of an odd number, that thus beginning to

ascend with the right foot, they might end with ihe same foot, which they took to be a

good omen, and a greater mark of respect so to enter iiUo the temple. It will be suflficient

to put eleven or tliirteen steps at most to a flight before coming to a half-pace, thus to help

weak people and of short breath, as well that they may there have the opportunity of

resting as to allow of any person falling from above being there caught." We lio not ])ro-

pose to give examples of other than the most usual forms of staircases and stairs; their

variety is almost infinite, and could not even in their leading features be compassed in a

work like this. The varieties, indeed, would not be usefully given, inasmuch as the forms

are necessarily dependent on the varied circumstances of each plan, calling upon the

architect almost on every occasion to invent pro re nata.

2805. Stairs are of two sorts, straight and winding. Before proceeding with his design,

the architect must always take care, whether in the straight or winding staircase, that the per-

son ascending has what is called headway, which is a clear distance measured vertically from

any step, quarter, half-pace, or landing, to the underside of the ceiling, step, or other part

immediately over it, so as to allow the tallest person to clear it with his hat on; and this is

the minimum height of headway that can be admitted. To return to the straight and

ivinding staircase, it is to be observed, that the first may be divided into t\ro Jlights, or be

The Vicentine foot is about 13-G inches English.

You might also like

- General Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsuranceDocument19 pagesGeneral Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsurancereacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1464)Document1 pageEn (1464)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1451)Document1 pageEn (1451)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1458)Document1 pageEn (1458)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1459)Document1 pageEn (1459)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocument1 pageMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1382)Document1 pageEn (1382)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocument1 pageAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1383)Document1 pageEn (1383)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- The The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesDocument1 pageThe The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1386)Document1 pageEn (1386)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1376)Document1 pageEn (1376)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1374)Document1 pageEn (1374)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1372)Document1 pageEn (1372)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- 13507Document5 pages13507Abinash Kumar0% (1)

- Community Resource MobilizationDocument17 pagesCommunity Resource Mobilizationerikka june forosueloNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument33 pagesProjectPiyush PatelNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Designing An Active Directory InfrastructureDocument18 pagesIntroduction To Designing An Active Directory InfrastructurepablodoeNo ratings yet

- Personal Narrative RevisedDocument3 pagesPersonal Narrative Revisedapi-549224109No ratings yet

- Assessing The Marks and Spencers Retail ChainDocument10 pagesAssessing The Marks and Spencers Retail ChainHND Assignment Help100% (1)

- Reference by John BatchelorDocument1 pageReference by John Batchelorapi-276994844No ratings yet

- P66 M10 CAT B Forms and Docs 04 10Document68 pagesP66 M10 CAT B Forms and Docs 04 10VinayNo ratings yet

- Marieb ch3dDocument20 pagesMarieb ch3dapi-229554503No ratings yet

- Donnan Membrane EquilibriaDocument37 pagesDonnan Membrane EquilibriamukeshNo ratings yet

- Chapter 13Document15 pagesChapter 13anormal08No ratings yet

- Contigency Plan On Class SuspensionDocument4 pagesContigency Plan On Class SuspensionAnjaneth Balingit-PerezNo ratings yet

- STARCHETYPE REPORT ReLOADED AUGURDocument5 pagesSTARCHETYPE REPORT ReLOADED AUGURBrittany-faye OyewumiNo ratings yet

- 7 ElevenDocument80 pages7 ElevenakashNo ratings yet

- A Process Reference Model For Claims Management in Construction Supply Chains The Contractors PerspectiveDocument20 pagesA Process Reference Model For Claims Management in Construction Supply Chains The Contractors Perspectivejadal khanNo ratings yet

- Tourbier Renewal NoticeDocument5 pagesTourbier Renewal NoticeCristina Marie DongalloNo ratings yet

- AMO Exercise 1Document2 pagesAMO Exercise 1Jonell Chan Xin RuNo ratings yet

- Asu 2019-12Document49 pagesAsu 2019-12janineNo ratings yet

- GA Power Capsule For SBI Clerk Mains 2024 (Part-2)Document82 pagesGA Power Capsule For SBI Clerk Mains 2024 (Part-2)aa1904bbNo ratings yet

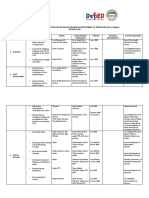

- Mother Tongue K To 12 Curriculum GuideDocument18 pagesMother Tongue K To 12 Curriculum GuideBlogWatch100% (5)

- 1 Prof Chauvins Instructions For Bingham CH 4Document35 pages1 Prof Chauvins Instructions For Bingham CH 4Danielle Baldwin100% (2)

- Report-Smaw Group 12,13,14Document115 pagesReport-Smaw Group 12,13,14Yingying MimayNo ratings yet

- Zambia National FormularlyDocument188 pagesZambia National FormularlyAngetile Kasanga100% (1)

- User ManualDocument96 pagesUser ManualSherifNo ratings yet

- Generator ControllerDocument21 pagesGenerator ControllerBrianHazeNo ratings yet

- Advantages Renewable Energy Resources Environmental Sciences EssayDocument3 pagesAdvantages Renewable Energy Resources Environmental Sciences EssayCemerlang StudiNo ratings yet

- Pontevedra 1 Ok Action PlanDocument5 pagesPontevedra 1 Ok Action PlanGemma Carnecer Mongcal50% (2)

- Cosmic Handbook PreviewDocument9 pagesCosmic Handbook PreviewnkjkjkjNo ratings yet

- PronounsDocument6 pagesPronounsHải Dương LêNo ratings yet

- Interbond 2340UPC: Universal Pipe CoatingDocument4 pagesInterbond 2340UPC: Universal Pipe Coatingnoto.sugiartoNo ratings yet