Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Unwanted, Unwelcome: Anti-Immigration Attitudes in Turkey

Uploaded by

German Marshall Fund of the United States0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

141 views3 pagesThis policy brief explains Turkish citizens' intolerance of immigrants and recommends actions to reverse this trend.

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis policy brief explains Turkish citizens' intolerance of immigrants and recommends actions to reverse this trend.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

141 views3 pagesUnwanted, Unwelcome: Anti-Immigration Attitudes in Turkey

Uploaded by

German Marshall Fund of the United StatesThis policy brief explains Turkish citizens' intolerance of immigrants and recommends actions to reverse this trend.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

Summary: As immigrants in

Turkey became more visible, so

did a previously hidden problem:

the intolerance of Turkish

citizens toward immigrants.

Several surveys reveal that

Turkish citizens have a less than

welcoming attitude regarding

immigrants, and this attitude

is often fanned by politicians

and the media. This policy brief

explains the reasons for this and

recommends actions to reverse

this trend.

Analysis

Unwanted, Unwelcome: Anti-Immigration

Attitudes in Turkey

by Emre Erdoan

September 10, 2014

Washington, DC Berlin Paris

Brussels Belgrade Ankara

Bucharest Warsaw

OF F I C E S

Analysis

Until the spread of the Arab Spring

and the confict in Syria, Turkey was

known as a sending country in terms

of international migration. When

it was founded in 1924, around 60

percent of the citizens of the young

Turkish republic were either frst-

or second-generation immigrants

from the former Ottoman realms.

More recently, according to available

statistics, only 2 percent of Turkeys

population immediately before the

Arab Spring consisted of immigrants

and the majority of those were from

ex-Ottoman territories, such as

Bosnia-Herzegovina and Bulgaria.

Immigrants became visible in Turkey

when the direction of migration fow

changed. Turkey became a transi-

tional country hosting more than

500,000 migrants from the Middle

Eastern, Asian, and African countries

who were looking for a way to Europe.

Tere are also 500,000 guest workers

from former-Soviet countries, and

Turkey has become very attractive for

asylum seekers frst from Iraq, and

now from Syria.

1

Currently, more than

1.1 million Syrians who have fed the

confict in their country live in Turkey,

and two-thirds of them are living

outside refugee camps.

1 Ahmet duygu, Turkeys Migration Transition and its

Implications for the Euro-Turkish Transnational Space,

http://www.iai.it/pdf/GTE/GTE_WP_07.pdf

As these people became more visible,

so did a previously hidden problem:

the intolerance of Turkish citizens

toward immigrants. Syrian immi-

grants have become frequent targets

of physical violence, especially in the

southeastern regions of country and

suburbs of larger cities. Tey have

replaced Africans and Eastern Euro-

peans as targets of hate speech in

written and social media from almost

every segment of society.

Tis situation is not surprising if

the results of several surveys are

compared. In the World Values Survey

covering 51 countries, Turkey is

ranked in 13

th

place third on the

European continent in terms of

intolerance toward immigrants and

foreign workers. Te results from the

Life in Transition Survey II (LITS2),

conducted in 2010, named Turkey as

the most intolerant nation among 34

European and Asian countries, tied

with Mongolia.

Te Transatlantic Trends 2014 Survey

of the German Marshall Fund of the

United States (GMF) provides further

evidence for the worsening percep-

tions of immigrants. According to

this survey, 42 percent of the Turkish

population thinks that there are too

many foreign-born people in Turkey,

Analysis

2

Analysis

a 17 percentage point increase over 2013. Moreover, 66

percent of the respondents from Turkey support more

restrictive policies toward refugees. Tis score is the highest

among the 13 countries covered by the report.

Tese negative perceptions are naturally associated with

the recent developments in the region. Sixty percent of the

Turkish society thinks that immigrants most common

motivation is seeking asylum. Te second-most popular

answer is seeking social benefts (17%). Although the

number of asylum seekers and foreign workers is almost

equal in reality, only 13% of Turkish respondents state

working as a major reason for immigration. Tis gap gives

hints about the immigrant stereotype in Turkish society:

they are asylum seekers.

Although negative perceptions about immigrants increased

in one year and there is a strong support for restrictions of

Turkeys policies toward refugees, this issue has not yet been

transferred to political sphere. Only 4 percent of Turks say

that immigration is Turkeys most important problem. By

comparison, this fgure is 25 percent in the U.K., 11 percent

in Germany, and 9 percent in the United States. Meanwhile,

the percentage of those approving of the governments

immigration policies is 27 percent; two-thirds of respon-

dents disapprove of them.

Considering the fact that almost half of the respondents

approve of how the government is handling international

policies in general, a 67 percent disapproval rate of immi-

gration policies indicates a broad criticism of the govern-

ment in this area.

Te Transatlantic Trends fndings are supported by other

surveys as well. According to a recent survey about nation-

alism in Turkey, conducted as a part of the International

Social Survey Programme, 65 percent of respondents think

that immigrants are increasing crime rates. More than half

of respondents think that immigrants are taking jobs away

from locals and that they undermine Turkish culture.

2

Tese

are clear indicators of an anti-immigrant public sentiment.

Te reasons for this negative sentiment are numerous and

open to speculation. Political scientists tend to explain

anti-immigrant attitudes from a threat perspective. As

nationals perceive a threat from immigrants, their anti-

2 Findings of Nationalism in Turkey, http://ipc.sabanciuniv.edu/wp-content/up-

loads/2014/06/Dunyada-ve-Turkiyede-Milliyetcilik-SON.pdf.

immigrant attitudes increase. Tis threat may be a material-

istic/realistic threat, such as when immigrants and nationals

compete for jobs and newcomers challenge the countrys

low-skilled labor force. Tese threat perceptions are not

necessarily objective; they are highly afected by group

identities. Moreover, competition is not limited to the jobs

market. Nationals may also perceive newcomers as burdens

on social service budgets and welfare expenditures.

Te second dimension of threat perception is symbolic, the

threat posed to the values, religion, and culture of the host

country. If citizens tend to perceive a gap between their

morals, values, norms, standards, beliefs, and attitudes and

those of immigrants, they tend to have more negative atti-

tudes about them. Treat perceptions may be multiplied or

reduced with the degree of contact with immigrants, educa-

tion, media literacy, social capital, or other political variables,

and these interactions vary from one country to another.

In the Turkish case, all of these explanations are valid to

some extent. A recent paper tried to discover determi-

nants of anti-immigrant attitudes in Turkey by using the

LITS2 data.

3

Te analyses showed that a higher level of

media literacy contributes to anti-immigrant attitudes in

Turkey, while there is no diference across socio-economic

and demographic groups. Tis fnding is not surprising

considering the xenophobic nature of Turkish media, which

amplifes politicians ofen negative statements about immi-

grants. Another fnding is that a materialistic/realistic threat

is not valid in the Turkish case, since there is no diference

between the responses of employed and unemployed and

lower and higher socio-economic status.

Meanwhile, analyses showed that the most important deter-

minants of anti-immigrant attitudes are intolerance toward

others in general. As one becomes more intolerant toward

3 Emre Erdoan and Pnar Uyan Semerci, Turkey: A Puzzling Case to Understand Public

Attitudes toward Immigrants, forthcoming.

A 67 percent disapproval rate of

immigration policies indicates a

broad criticism of the government

in this area.

Analysis

3

Analysis

Te views expressed in GMF publications and commentary are the

views of the author alone.

About the Author

Emre Erdoan, Ph.D., is an expert in public opinion and foreign

policy. He is one of the founders of Infakto RW, an Istanbul-based

independent research institute, and a professor of political method-

ology in Istanbul Bilgi University and Boazii University. Erdoan is

author of several articles about public opinion, foreign policy, political

participation, and social capital. Tey Know Us Wrongly, about percep-

tions of Europeans regarding Turks and Turkey, was published in 2012.

About GMF

Te German Marshall Fund of the United States (GMF) strengthens

transatlantic cooperation on regional, national, and global challenges

and opportunities in the spirit of the Marshall Plan. GMF does this by

supporting individuals and institutions working in the transatlantic

sphere, by convening leaders and members of the policy and business

communities, by contributing research and analysis on transatlantic

topics, and by providing exchange opportunities to foster renewed

commitment to the transatlantic relationship. In addition, GMF

supports a number of initiatives to strengthen democracies. Founded

in 1972 as a non-partisan, non-proft organization through a gif from

Germany as a permanent memorial to Marshall Plan assistance, GMF

maintains a strong presence on both sides of the Atlantic. In addition

to its headquarters in Washington, DC, GMF has ofces in Berlin,

Paris, Brussels, Belgrade, Ankara, Bucharest, and Warsaw. GMF also

has smaller representations in Bratislava, Turin, and Stockholm.

About the On Turkey Series

GMFs On Turkey is an ongoing series of analysis briefs about Turkeys

current political situation and its future. GMF provides regular

analysis briefs by leading Turkish, European, and U.S. writers and

intellectuals, with a focus on dispatches from on-the-ground Turkish

observers. To access the latest briefs, please visit our web site at www.

gmfus.org/turkey.

others, his/her propensity to also have an anti-immigrant atti-

tude almost doubles. For example, people who are intolerant

of drug addicts, people who have AIDS, or heavy drinkers

are two times more likely to have an anti-immigrant attitude.

Tis shows that intolerance of immigrants is a part of the

overall intolerance of Turkish society, which is known for a

high level of xenophobia and where the presence of foreign

workers/immigrants is perceived as a moral threat.

Tis means that the anti-immigrant climate of Turkish

society is not a short-term problem but can be traced back

to the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire and the humani-

tarian tragedy caused by this dissolution and the resulting

independence wars.

4

Te Turkish education system fosters xenophobic attitudes

through its very nationalistic and exclusionary content.

Politicians exploit these attitudes to mobilize voters and

consolidate their constituencies by creating virtual eternal

enemies.

5

Te Turkish media, which is largely dependent

on the government resources, amplify these techniques, and

independent voices are rarely audible. Turkish citizens are

naively proud of themselves, according to the nationalism

survey: Turks are Turks and one striking fact is that we

[asked] if everybody would be a Turk, would the world be a

better place, and Turks gave a very high rating.

6

Transatlantic Trends shows that these characteristics have

been accentuated by the emergency situation in Syria. Te

increased visibility of Syrian refugees has created signif-

cant public discontent, shown by hate speech and physical

violence. Very low support for government policies about

immigration and large demand for restrictive policies are

more indications of a xenophobic climate and hostility

toward immigrants and refugees. Tese fault lines may

contribute to political polarization in Turkey, along with

rising nationalist tensions.

Deep-rooted problems cannot be solved with quick thera-

pies. Tis xenophobic environment is a product of decades

and it will take decades to remedy it. However, the emer-

gency situation in the region and a possible fow of more

4 More on this can be read in The Unbearable Heaviness of Being a Turkish Citizen, by

Dr. Emre Erdoan.

5 http://www.gmfus.org/archives/the-unbearable-heaviness-of-being-a-turkish-citizen/

6 Barn Yinan Turkish people are naively proud of themselves, survey shows http://

www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-people-are-naively-proud-of-themselves-survey-

shows.aspx?pageID=238&nID=69912&NewsCatID=338

refugees to Turkey, not only from Syria but also from Iraq

Yazidis, Kurds, Turkomans cannot wait for slow-

motion solutions. Some urgent measures need to be taken

in order to create a welcoming environment for those are

in need. Tese measures would ideally include a public

campaign to reduce the negative stereotypes about immi-

grants and encourage citizens to adopt a more hospitable

attitude toward them.

You might also like

- Persecution of Hizmet in TurkeyDocument37 pagesPersecution of Hizmet in TurkeyPeaceIslandsNo ratings yet

- International Migration in the Euro-Mediterranean Region: Cairo Papers in Social Science Vol. 35, No. 2From EverandInternational Migration in the Euro-Mediterranean Region: Cairo Papers in Social Science Vol. 35, No. 2No ratings yet

- The Nuer: A Classic Case Study in AnthropologyDocument51 pagesThe Nuer: A Classic Case Study in Anthropologybrettbed100% (2)

- Calvin's Four Orders of Ecclesiastical GovernmentDocument5 pagesCalvin's Four Orders of Ecclesiastical GovernmentJovy MacholoweNo ratings yet

- Lebanon's Hostility To Syrian Refugees: Nils HägerdalDocument8 pagesLebanon's Hostility To Syrian Refugees: Nils HägerdalCrown Center for Middle East StudiesNo ratings yet

- Surviving in Limbo - Lived ExperiencesDocument64 pagesSurviving in Limbo - Lived ExperiencesAssaf - Aid organization for refugees & asylum seekers in IsraelNo ratings yet

- ADFA IRF FolderDocument20 pagesADFA IRF FolderADemandForActionNo ratings yet

- Refugee EbookDocument17 pagesRefugee Ebookapi-314186269No ratings yet

- Chapter IIDocument265 pagesChapter IIbrianpdNo ratings yet

- Displaced Women and Girls at RiskDocument56 pagesDisplaced Women and Girls at RiskEmil KledenNo ratings yet

- Human Rights and Forced MigrationDocument10 pagesHuman Rights and Forced MigrationAnindito WiraputraNo ratings yet

- Promoting and Protecting The Rights of Migrant Workers: A Manual For National Human Rights Institutions.Document252 pagesPromoting and Protecting The Rights of Migrant Workers: A Manual For National Human Rights Institutions.Global Justice Academy100% (1)

- Refugees and the Transformation of Societies: Agency, Policies, Ethics and PoliticsFrom EverandRefugees and the Transformation of Societies: Agency, Policies, Ethics and PoliticsNo ratings yet

- Island of Hope: Migration and Solidarity in the MediterraneanFrom EverandIsland of Hope: Migration and Solidarity in the MediterraneanNo ratings yet

- Unit 1: Atmosphere, Environment and Climate ChangeDocument24 pagesUnit 1: Atmosphere, Environment and Climate Changenidhi140286No ratings yet

- Report of The Symposium On RefugeesDocument5 pagesReport of The Symposium On Refugeesernesto_vialvaNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Effects of Syrian Refugees Crisis On LebanonDocument11 pagesA Review of The Effects of Syrian Refugees Crisis On LebanonTI Journals Publishing100% (1)

- Kenya's Somali North East Devolution and SecurityDocument20 pagesKenya's Somali North East Devolution and SecurityInternational Crisis Group100% (1)

- Refugee Rights PDFDocument84 pagesRefugee Rights PDFJames AriasNo ratings yet

- William Carey International Development Journal Winter 2012Document63 pagesWilliam Carey International Development Journal Winter 2012William Carey International University PressNo ratings yet

- HumanRightsTheory&Practice WaltersDocument17 pagesHumanRightsTheory&Practice Walterswilliamw39No ratings yet

- Tibus Thesis UCCP StudyDocument128 pagesTibus Thesis UCCP StudyReyLouise0% (1)

- Turkey's Defense Procurement Behavior: A Gramscian Analysis (1923-2013Document338 pagesTurkey's Defense Procurement Behavior: A Gramscian Analysis (1923-2013Mikhael DananNo ratings yet

- Olsen, Carstensen and Høyen (2003) Humanitarian Crises - Testing The 'CNN Effect'Document3 pagesOlsen, Carstensen and Høyen (2003) Humanitarian Crises - Testing The 'CNN Effect'mirjanaborotaNo ratings yet

- Review of Political History of Pare People Up To 1900 by MapundaDocument12 pagesReview of Political History of Pare People Up To 1900 by MapundaDonasian Mbonea Elisante Mjema100% (1)

- Press Release, 14 JulyDocument2 pagesPress Release, 14 JulyADemandForActionNo ratings yet

- Urbanisation and MigrationDocument39 pagesUrbanisation and MigrationPALLAVINo ratings yet

- War and Famine in AfricaDocument41 pagesWar and Famine in AfricaOxfamNo ratings yet

- Turkey's Neighborhood Policy: A European PerspectiveDocument6 pagesTurkey's Neighborhood Policy: A European PerspectiveGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Assignment Terrorism and Its Inpact On SocietyDocument6 pagesAssignment Terrorism and Its Inpact On SocietyNimra amirNo ratings yet

- Migration and Remittances during the Global Financial Crisis and BeyondFrom EverandMigration and Remittances during the Global Financial Crisis and BeyondNo ratings yet

- Reinventing the Republic: Gender, Migration, and Citizenship in FranceFrom EverandReinventing the Republic: Gender, Migration, and Citizenship in FranceNo ratings yet

- The Manifestation of Islam in ArgentinaDocument20 pagesThe Manifestation of Islam in ArgentinaSolSomozaNo ratings yet

- MigrationDocument12 pagesMigrationPooza SunuwarNo ratings yet

- Principles of Turkish Foreign Policy and Regional Political StructuringDocument9 pagesPrinciples of Turkish Foreign Policy and Regional Political StructuringInternational Policy and Leadership InstituteNo ratings yet

- Turkey and West IneterstDocument32 pagesTurkey and West Ineterstخود پەناNo ratings yet

- 122 NGOs providing aid to Rohingyas in Cox's BazarDocument28 pages122 NGOs providing aid to Rohingyas in Cox's Bazarruslan3089No ratings yet

- Research ProposalDocument35 pagesResearch ProposalMulugeta Bariso100% (3)

- Political Activities of Turkey and The Turkish Cypriots, 1945-1958 (By Stella Soulioti)Document9 pagesPolitical Activities of Turkey and The Turkish Cypriots, 1945-1958 (By Stella Soulioti)Macedonia - The Authentic TruthNo ratings yet

- Report On Racial Discrimination Genocide Refugees and Stateless Persons With NamesDocument20 pagesReport On Racial Discrimination Genocide Refugees and Stateless Persons With NamesJohn Soap Reznov MacTavishNo ratings yet

- HUMAN RIGHTS WordDocument98 pagesHUMAN RIGHTS Wordkounain fathimaNo ratings yet

- Urban Profiling of Refugees Situations in DelhiDocument86 pagesUrban Profiling of Refugees Situations in DelhiFeinstein International CenterNo ratings yet

- Natural Resources and Conflict in Africa - Cairo Conference ReportwAnnexes Nov 17Document72 pagesNatural Resources and Conflict in Africa - Cairo Conference ReportwAnnexes Nov 17Davide DentiNo ratings yet

- Islam Foreign Policy Final VersionDocument10 pagesIslam Foreign Policy Final VersionAniko GáspárNo ratings yet

- Article National Power and Grand StrategyDocument11 pagesArticle National Power and Grand StrategySadiya AzharNo ratings yet

- Turkey: The I Slamist-Secularist Divide.Document10 pagesTurkey: The I Slamist-Secularist Divide.Institute for the Study of Secularism in Society and Culture100% (2)

- Muslims in the West and the Challenges of BelongingFrom EverandMuslims in the West and the Challenges of BelongingNo ratings yet

- Responding To The Refugee CrisisDocument45 pagesResponding To The Refugee Crisiszoran-888No ratings yet

- Singapore's History as a Global Trading HubDocument25 pagesSingapore's History as a Global Trading HubGirish NarayananNo ratings yet

- Humanitarian Key FactsDocument6 pagesHumanitarian Key FactsOxfamNo ratings yet

- Anti Secular Manifesto PDFDocument31 pagesAnti Secular Manifesto PDFSVD ChandrasekharNo ratings yet

- Portrayal of Muslims in Western MediaDocument10 pagesPortrayal of Muslims in Western MediasulaimanNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Diversity, Development and Social Policy in Small States: The Case of Mauritius by Yeti Nisha Madhoo and Shyam NathDocument68 pagesEthnic Diversity, Development and Social Policy in Small States: The Case of Mauritius by Yeti Nisha Madhoo and Shyam NathUnited Nations Research Institute for Social DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Bangladesh Development Model Challenges of SustainabilityDocument10 pagesBangladesh Development Model Challenges of SustainabilityAbu Sufian ShamratNo ratings yet

- Statement by Dr. Francis Mading DengDocument10 pagesStatement by Dr. Francis Mading DengAbyeiReferendum2013100% (1)

- Kurdish AwakeningDocument16 pagesKurdish AwakeningZeinab KochalidzeNo ratings yet

- Lasa Forum Nuevas Agendas para Una Antigua Migración: La Migración Siria, Libanesa y Palestina Desde Una Mirada LatinoamericanaDocument36 pagesLasa Forum Nuevas Agendas para Una Antigua Migración: La Migración Siria, Libanesa y Palestina Desde Una Mirada LatinoamericanajorgeNo ratings yet

- LuxembourgDocument16 pagesLuxembourgapi-341938434100% (1)

- Cooperation in The Midst of Crisis: Trilateral Approaches To Shared International ChallengesDocument34 pagesCooperation in The Midst of Crisis: Trilateral Approaches To Shared International ChallengesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Turkey's Travails, Transatlantic Consequences: Reflections On A Recent VisitDocument6 pagesTurkey's Travails, Transatlantic Consequences: Reflections On A Recent VisitGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The Iranian Moment and TurkeyDocument4 pagesThe Iranian Moment and TurkeyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Isolation and Propaganda: The Roots and Instruments of Russia's Disinformation CampaignDocument19 pagesIsolation and Propaganda: The Roots and Instruments of Russia's Disinformation CampaignGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Small Opportunity Cities: Transforming Small Post-Industrial Cities Into Resilient CommunitiesDocument28 pagesSmall Opportunity Cities: Transforming Small Post-Industrial Cities Into Resilient CommunitiesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Why Russia's Economic Leverage Is DecliningDocument18 pagesWhy Russia's Economic Leverage Is DecliningGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The Awakening of Societies in Turkey and Ukraine: How Germany and Poland Can Shape European ResponsesDocument45 pagesThe Awakening of Societies in Turkey and Ukraine: How Germany and Poland Can Shape European ResponsesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- For A "New Realism" in European Defense: The Five Key Challenges An EU Defense Strategy Should AddressDocument9 pagesFor A "New Realism" in European Defense: The Five Key Challenges An EU Defense Strategy Should AddressGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Turkey: Divided We StandDocument4 pagesTurkey: Divided We StandGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Defending A Fraying Order: The Imperative of Closer U.S.-Europe-Japan CooperationDocument39 pagesDefending A Fraying Order: The Imperative of Closer U.S.-Europe-Japan CooperationGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The West's Response To The Ukraine Conflict: A Transatlantic Success StoryDocument23 pagesThe West's Response To The Ukraine Conflict: A Transatlantic Success StoryGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The United States in German Foreign PolicyDocument8 pagesThe United States in German Foreign PolicyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Solidarity Under Stress in The Transatlantic RealmDocument32 pagesSolidarity Under Stress in The Transatlantic RealmGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- China's Risk Map in The South AtlanticDocument17 pagesChina's Risk Map in The South AtlanticGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Between A Hard Place and The United States: Turkey's Syria Policy Ahead of The Geneva TalksDocument4 pagesBetween A Hard Place and The United States: Turkey's Syria Policy Ahead of The Geneva TalksGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Common Ground For European Defense: National Defense and Security Strategies Offer Building Blocks For A European Defense StrategyDocument6 pagesCommon Ground For European Defense: National Defense and Security Strategies Offer Building Blocks For A European Defense StrategyGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Turkey Needs To Shift Its Policy Toward Syria's Kurds - and The United States Should HelpDocument5 pagesTurkey Needs To Shift Its Policy Toward Syria's Kurds - and The United States Should HelpGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Russia's Military: On The Rise?Document31 pagesRussia's Military: On The Rise?German Marshall Fund of the United States100% (1)

- Pride and Pragmatism: Turkish-Russian Relations After The Su-24M IncidentDocument4 pagesPride and Pragmatism: Turkish-Russian Relations After The Su-24M IncidentGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- AKParty Response To Criticism: Reaction or Over-Reaction?Document4 pagesAKParty Response To Criticism: Reaction or Over-Reaction?German Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Brazil and Africa: Historic Relations and Future OpportunitiesDocument9 pagesBrazil and Africa: Historic Relations and Future OpportunitiesGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Leveraging Europe's International Economic PowerDocument8 pagesLeveraging Europe's International Economic PowerGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- The EU-Turkey Action Plan Is Imperfect, But Also Pragmatic, and Maybe Even StrategicDocument4 pagesThe EU-Turkey Action Plan Is Imperfect, But Also Pragmatic, and Maybe Even StrategicGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- After The Terror Attacks of 2015: A French Activist Foreign Policy Here To Stay?Document23 pagesAfter The Terror Attacks of 2015: A French Activist Foreign Policy Here To Stay?German Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- How Economic Dependence Could Undermine Europe's Foreign Policy CoherenceDocument10 pagesHow Economic Dependence Could Undermine Europe's Foreign Policy CoherenceGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Turkey and Russia's Proxy War and The KurdsDocument4 pagesTurkey and Russia's Proxy War and The KurdsGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Whither The Turkish Trading State? A Question of State CapacityDocument4 pagesWhither The Turkish Trading State? A Question of State CapacityGerman Marshall Fund of the United StatesNo ratings yet

- Russia's Long War On UkraineDocument22 pagesRussia's Long War On UkraineGerman Marshall Fund of the United States100% (1)

- This Content Downloaded From 181.65.56.6 On Mon, 12 Oct 2020 21:09:21 UTCDocument23 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 181.65.56.6 On Mon, 12 Oct 2020 21:09:21 UTCDennys VirhuezNo ratings yet

- MBA Capstone Module GuideDocument25 pagesMBA Capstone Module GuideGennelyn Grace PenaredondoNo ratings yet

- Defining Corporate Social ResponsibilityDocument12 pagesDefining Corporate Social ResponsibilityYzappleNo ratings yet

- Managing The Law The Legal Aspects of Doing Business 3rd Edition Mcinnes Test BankDocument19 pagesManaging The Law The Legal Aspects of Doing Business 3rd Edition Mcinnes Test Banksoutacheayen9ljj100% (22)

- Pratshirdi Shri Sai Mandir'ShirgaonDocument15 pagesPratshirdi Shri Sai Mandir'ShirgaonDeepa HNo ratings yet

- CBS NewsDocument21 pagesCBS Newstfrcuy76No ratings yet

- Mission Youth PPT (Ramban) 06-11-2021Document46 pagesMission Youth PPT (Ramban) 06-11-2021BAWANI SINGHNo ratings yet

- AXIOLOGY PowerpointpresntationDocument16 pagesAXIOLOGY Powerpointpresntationrahmanilham100% (1)

- The Paombong Public MarketDocument2 pagesThe Paombong Public MarketJeonAsistin100% (1)

- Jesu, Joy of Mans DesiringDocument6 pagesJesu, Joy of Mans DesiringAleksandar TamindžićNo ratings yet

- SFL - Voucher - MOHAMMED IBRAHIM SARWAR SHAIKHDocument1 pageSFL - Voucher - MOHAMMED IBRAHIM SARWAR SHAIKHArbaz KhanNo ratings yet

- The Human Person As An Embodied SpiritDocument8 pagesThe Human Person As An Embodied SpiritDrew TamposNo ratings yet

- History of Brunei Empire and DeclineDocument4 pagesHistory of Brunei Empire and Declineたつき タイトーNo ratings yet

- The War Against Sleep - The Philosophy of Gurdjieff by Colin Wilson (1980) PDFDocument50 pagesThe War Against Sleep - The Philosophy of Gurdjieff by Colin Wilson (1980) PDFJosh Didgeridoo0% (1)

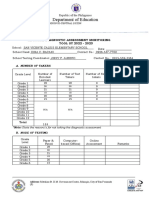

- Regional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Document3 pagesRegional Diagnostic Assessment Report SY 2022-2023Dina BacaniNo ratings yet

- Financial Analysis Premier Cement Mills LimitedDocument19 pagesFinancial Analysis Premier Cement Mills LimitedMd. Harunur Rashid 152-11-4677No ratings yet

- RoughGuide之雅典Document201 pagesRoughGuide之雅典api-3740293No ratings yet

- Montaner Vs Sharia District Court - G.R. No. 174975. January 20, 2009Document6 pagesMontaner Vs Sharia District Court - G.R. No. 174975. January 20, 2009Ebbe DyNo ratings yet

- The Value of EquityDocument42 pagesThe Value of EquitySYAHIER AZFAR BIN HAIRUL AZDI / UPMNo ratings yet

- Florence Nightingale's Advocacy in NursingDocument15 pagesFlorence Nightingale's Advocacy in NursingCoky Jamesta Kasih KasegerNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Asset Pricing ModelDocument8 pagesIntroduction To Asset Pricing ModelHannah NazirNo ratings yet

- Definition of Internal Order: Business of The Company (Orders With Revenues)Document6 pagesDefinition of Internal Order: Business of The Company (Orders With Revenues)MelanieNo ratings yet

- Helen Meekosha - Decolonising Disability - Thinking and Acting GloballyDocument17 pagesHelen Meekosha - Decolonising Disability - Thinking and Acting GloballyjonakiNo ratings yet

- Intern Ship Final Report Henok MindaDocument43 pagesIntern Ship Final Report Henok Mindalemma tseggaNo ratings yet

- Variety July 19 2017Document130 pagesVariety July 19 2017jcramirezfigueroaNo ratings yet

- R164Document9 pagesR164bashirdarakNo ratings yet

- EVADocument34 pagesEVAMuhammad GulzarNo ratings yet

- Tawfīq Al - Akīm and The West PDFDocument12 pagesTawfīq Al - Akīm and The West PDFCosmin MaricaNo ratings yet

- 320-326 Interest GroupsDocument2 pages320-326 Interest GroupsAPGovtPeriod3No ratings yet

- Chapter 1: Solving Problems and ContextDocument2 pagesChapter 1: Solving Problems and ContextJohn Carlo RamosNo ratings yet