Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fencing

Uploaded by

Marie CecileCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fencing

Uploaded by

Marie CecileCopyright:

Available Formats

ANTI-FENCING LAW OF 1979 (PD NO.

1612)

DEFINITION

Fencing as defined in Sec. 2 of PD No. 1612 (Anti-Fencing Law) is the act of any person

who, with intent to gain for himself or for another, shall buy, receive, possess, keep,

acquire, conceal, sell or dispose of, or shall buy and sell, or in any manner deal in any

article, item, object or anything of value which he knows or should be known to him, or to

have been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft. (Dizon-Pamintuan vs.

People, GR 111426, 11 July 94).

BRIEF HISTORY OF PD 1612 OR THE ANTI-FENCING LAW

Presidential Decree No. 1612 or commonly known as the Anti-Fencing Law of 1979 was

enacted under the authority of therein President Ferdinand Marcos. The law took effect on

March 2, 1979. The Implementing Rules and Regulations of the Anti-Fencing Law were

subsequently formulated and it took effect on June 15, 1979.

THE PURPOSE OF ENACTING PD 1612

The Anti-Fencing Law was made to curtail and put an end to the rampant robbery of

government and private properties. With the existence of ready buyers, the business of

robbing and stealing have become profitable. Hence, a law was enacted to also punish those

who buy stolen properties. For if there are no buyers then the malefactors could not profit

from their wrong doings.

WHAT IS FENCING LAW AND HOW IT CAN BE COMMITTED

Fencing is the act of any person who, with intent to gain for himself or for another, shall

buy receive, possess, keep, acquire, conceal, sell or dispose of, or shall buy and sell, or in

any other manner deal in any article, item, object or anything of value which he knows, or

should be known to him, to have been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery or

theft. A Fence includes any person, firm, association corporation or partnership or other

organization who/ which commits the act of fencing.

WHO ARE LIABLE FOR THE CRIME OF FENCING; AND ITS PENALTIES:

The person liable is the one buying, keeping, concealing and selling the stolen items. If the

fence is a corporation, partnership, association or firm, the one liable is the president or the

manager or the officer who knows or should have know the fact that the offense was

committed.

The law provide for penalty range for persons convicted of the crime of fencing. Their

penalty depends on the value of the goods or items stolen or bought:

A. The penalty of prision mayor, if the value of the property involved is more than 12,000

pesos but not exceeding 22,000 pesos; if the value of such property exceeds the latter sum,

the penalty provided in this paragraph shall be imposed in its maximum period, adding one

year for each additional 10,000 pesos; but the total penalty which may be imposed shall not

exceed twenty years. In such cases, the penalty shall be termed reclusion temporal and the

accessory penalty pertaining thereto provided in the Revised Penal Code shall also be

imposed.

B. The penalty of prision correccional in its medium and maximum periods, if the value of

the property robbed or stolen is more than 6,000 pesos but not exceeding 12, 000 pesos;

C. The penalty of prision correccional in its minimum and medium periods, if the value of

the property involved is more than 200 pesos but not exceeding 6,000 pesos;

D. The penalty of arresto mayor in its medium period to prision correccional in its

minimum period, if the value of the property involved is over 50 but not exceeding 200

pesos;

E. The penalty of arresto mayor in its medium period if such value is over five (5) pesos but

not exceeding 50 pesos.

F. The penalty of arresto mayor in its minimum period if such value does not exceed 5

pesos.

RULES REGARDING BUY AND SELL OF GOODS PARTICULARLY SECOND HAND GOODS

The law requires the establishment engaged in the buy and sell of goods to obtain a

clearance or permit to sell used second hand items, to give effect to the purpose of the

law in putting an end to buying and selling stolen items. Failure of which makes the owner

or manager liable as a fence.

The Implementing Rules provides for the guidelines of issuance of clearances or permits to

sell used or secondhand items. It provided for the definition of the following terms:

Used secondhand article shall refer to any goods, article, items, object or anything of

value obtained from an unlicensed dealer or supplier, regardless of whether the same has

actually or in fact been used.

Unlicensed dealer/supplier shall refer to any persons, partnership, firm, corporation,

association or any other entity or establishment not licensed by the government to engage

in the business of dealing in or of supplying the articles defined in the preceding paragraph;

Store, establishment or entity shall be construed to include any individual dealing in

the buying and selling used secondhand articles, as defined in paragraph hereof;

Buy and Sell refer to the transaction whereby one purchases used secondhand articles for

the purpose of resale to third persons;

Station Commander shall refer to the Station Commander of the Integrated National

Police within the territorial limits of the town or city district where the store,

establishment or entity dealing in the buying and selling of used secondhand

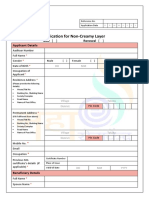

PROCEDURE FOR SECURING PERMIT/CLEARANCE

The Implementing Rules provided for the method of obtaining clearance or permit. No fee

will be charged for the issuance of the clearance/permit. Failure to secure

clearance/permit shall be punished as a fence, that may result to the cancellation of

business license.

1. The Station Commander shall require the owner of a store or the President, manager or

responsible officer in having in stock used secondhand articles, to submit an initial affidavit

within thirty (30) days from receipt of notice for the purpose thereof and subsequent

affidavits once every fifteen (15) days within five (5) days after the period covered, which

shall contain:

a. complete inventory of such articles including the names and addresses from whom the

articles were acquired.

b. Full list of articles to be sold or offered for sale including the time and place of sale

c. Place where the articles are presently deposited. The Station Commander may, require

the submission of an affidavit accompanied by other documents showing proof of

legitimacy of acquisition.

2. Those who wish to secure the permit/clearance, shall file an application with the Station

Commander concerned, which states:

a. name, address and other pertinent circumstances

b. article to be sold or offered for sale to the public and the name and address of the

unlicensed dealer or supplier from whom such article was acquired.

c. Include the receipt or document showing proof of legitimacy of acquisition.

3. The Station Commander shall examine the documents attached to the application and

may require the presentation of other additional documents, if necessary, to show

satisfactory proof of the legitimacy of acquisition of the article, subject to the following

conditions:

a. if the Station Commander is not satisfied with the proof of legitimacy of acquisition, he

shall cause the publication of the notice, at the expense of the one seeking

clearance/permit, in a newspaper of general circulation for two consecutive days, stating:

articles acquired from unlicensed dealer or supplier

the names and addresses of the persons from whom they were acquired

that such articles are to be sold or offered for sale to the public at the address of the store,

establishment or other entity seeking the clearance/permit.

4. If there are no newspapers in general circulation, the party seeking the clearance/permit

shall, post a notice daily for one week on the bulletin board of the municipal building of the

town where the store, firm, establishment or entity is located or, in the case of an

individual, where the articles in his possession are to be sold or offered for sale.

5. If after 15 days, upon expiration of the period of publication or of the notice, no claim is

made to any of the articles enumerated in the notice, the Station Commander shall issue the

clearance or permit sought.

6. If before expiration of the same period for the publication of the notice or its posting, it

shall appear that any of the articles in question is stolen property, the Station Commander

shall hold the article in restraint as evidence in any appropriate case to be filed.

Articles held in restraint shall kept and disposed of as the circumstances of each case

permit. In any case it shall be the duty of the Station Commander concerned to

advise/notify the Commission on Audit of the case and comply with such procedure as may

be proper under applicable existing laws, rules and regulations.

7. The Station Commander shall, within seventy-two (72) hours from receipt of the

application, act thereon by either issuing the clearance/permit requested or denying the

same. Denial of an application shall be in writing and shall state in brief the reason/s

thereof.

8. Any party not satisfied with the decision of the Station Commander may appeal the same

within 10 days to the proper INP (now PNP) District Superintendent and further to the INP

(now PNP) Director. The decision of the Director can still be appealed top the Director-

General, within 10 days, whose decision may be appealed with the Minister (now

Secretary) of National Defense, within 15 days, which decision is final.

PRESUMPTION

Mere possession of any good, article, item, object or anything fo value which has been the

subject of robbery or thievery, shall be prima facie evidence of fencing.

ELEMENTS

A crime of robbery or theft has been committed;

The accused, who is not a principal or accomplice in the commission of the crime of

robbery or theft, buys, receives, possess, keeps, acquires, conceals, sells, or disposes, or

buys and sells, or in any manner deals in any article, item, object or anything of value,

which has been derived from the proceeds of the said crime;

The accused knows or should have known that the said article, item, or object or anything

of value has been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft; and

There is, on the part of the accused, intent to gain for himself or for another.(Dizon-

Pamintuan vs People, GR 111426, 11 July 94)

As regards the first element, the crime of robbery or theft should have been committed

before crime of fencing can be committed. The person committing the crime of robbery or

theft, may or may not be the same person committing the crime of fencing. As in the case of

D.M. Consunji, Inc., vs. Esguerra, quantities of phelonic plywood were stolen and the Court

held that qualified theft had been committed. In People vs. Lucero there was first a

snatching incident, where the bag of Mrs. Maripaz Bernard Ramolete was snatch in the

public market of Carbon, Cebu City, where she lost a Chinese Gold Necklace and pendant

worth some P4,000.00 to snatchers Manuel Elardo and Zacarias Pateras. The snatchers sold

the items to Manuel Lucero. Consequently, Lucero was charged with violation of the Anti-

Fencing Law. However, in this case, no eyewitness pointed to Lucero as the perpetrator and

the evidence of the prosecution was not strong enough to convict him.

The second element speaks of the overt act of keeping, buying, receiving, possessing,

acquiring, concealing, selling or disposing or in any manner deals with stolen items. It is

thus illustrated in the case of Lim vs. Court of Appeals, where the accused, Juanito Lim

stored and kept in his bodega and subsequently bought or disposed of the nine (9) pieces of

stolen tires with rims owned by Loui Anton Bond.

The accused known or should have known that the goods were stolen. As pointed out in the

case of People vs. Adriatico, the court in convicting Norma Adriatico, stated that it was

impossible for her to know that the jewelry were stolen because of the fact that Crisilita

was willing to part with a considerable number of jewelry at measly sum, and this should

have apprised Norma of the possibility that they were stolen goods. The approximate total

value of the jewelry were held to be at P20,000.00, and Norma having bought it from

Crisilita for only P2,700. The court also considered the fact that Norma engage in the

business of buying and selling gold and silver, which business is very well exposed to the

practice of fencing. This requires more than ordinary case and caution in dealing with

customers. As noted by the trial court:

. . . the Court is not inclined to accept the accuseds theory of buying in good faith and

disclaimer of ever seeing, much more, buying the other articles. Human experience belies

her allegations as no businessman or woman at that, would let go of such opportunities for

a clean profit at the expense of innocent owners.

The Court in convicting Ernesto Dunlao Sr., noted that the stolen articles composed of

farrowing crates and G.I. pipes were found displayed on petitioners shelves inside his

compound. (Dunalao, Sr. v. CA, 08/22/96)

In the case of People v. Muere (G.R.12902, 10/18/94), the third element was not proven.

This case involves the selling of alleged stolen Kenwood Stereo Unit in the store Danvir

Trading, owned by the spouses Muere. The store is engaged in buying and selling of second

hand merchandise located at Pasay Road, Makati. The said stereo was bought from Wynns

Audio, an existing establishment. The court held that there is no proof that the spouses

Muere, had knowledge of the fact that the stereo was stolen. The spouses Muere purchased

the stereo from a known merchant and the unit is displayed for sale in their store. These

actions are not indicative of a conduct of a guilty person.

On the same vein, the third element did not exist in the case of D.M. Consunji, Inc.(Consunji

v. Esguerra, 07/30/96) where the subject of the court action are the alleged stolen phelonic

plywood owned by D.M. Consunji, Inc., later found to be in the premises of MC Industrial

Sales and Seato trading Company, owned respectively by Eduardo Ching and the spouses

Sy. Respondents presented sales receipts covering their purchase of the items from

Paramount Industrial, which is a known hardware store in Caloocan, thus they had no

reason to suspect that the said items were products of theft.

The last element is that there is intent to gain for himself or for another. However, intent to

gain need not be proven in crimes punishable by a special law such as the Anti-Fencing

Law. The crimes punishable by special laws are called acts mala prohibita. The rule on the

subject is that in acts mala prohibita, the only inquiry is that, has the law been violated? (in

Gatdner v. People, as cited in US v. Go Chico, 14 Phils. 134) When the act is prohibited by

law, intent is immaterial.

Likewise, dolo or deceit is immaterial in crimes punishable by special statute like the Anti-

Fencing Law. It is the act itself which constitutes the offense and not the motive or intent.

Intent to gain is a mental state, the existence if which is demonstrated by the overt acts of

the person. The mental state is presumed from the commission of an unlawful act. (Dunlao

v. CA) again, intent to gain is a mental state, the existence of which is demonstrated by the

overt acts of person, as the keeping of stolen items for subsequent selling.

A FENCE MAY BE PROSECUTED UNDER THE RPC OR PD 1612

The state may thus choose to prosecute him either under the RPC or PD NO. 1612 although

the preference for the latter would seem inevitable considering that fencing is amalum

prohibitum, and PD No. 1612 creates a presumption of fencing and prescribes a higher

penalty based on the value of the property. (supra)

MERE POSSESSION OF STOLEN ARTICLE PRIMA FACIE EVIDENCE OF FENCING

Since Sec. 5 of PD NO. 1612 expressly provides that mere possession of any good, article,

item, object or anything of value which has been the subject of robbery or thievery shall be

prima facie evidence of fencing it follows that the accused is presumed to have knowledge

of the fact that the items found in her possession were the proceeds of robbery or theft. The

presumption does not offend the presumption of innocence enshrined in the fundamental

law.

DISTINCTION BETWEEN FENCING AND ROBBERY

The law on fencing does not require the accused to have participation in the criminal

design to commit or to have been in any wise involved in the commission of the crime of

robbery or theft. Neither is the crime of robbery or theft made to depend on an act of

fencing in order that it can be consummated. (People v De Guzman, GR 77368).

Robbery is the taking of personal property belonging to another, with intent to gain, by

means of violence against or intimidation of any person, or using force upon anything.

On the other hand, fencing is the act of any person who, with intent to gain for himself or

for another, shall buy, receive, possess, keep, acquire, conceal, sell or dispose of, or shall

buy and sell, or in any other manner deal in any article, item, object or anything of value

which he knows, or shall be known to him, to have been derived from the proceeds of the

crime of robbery or theft.

FENCING AS A CRIME INVOLVING MORAL TURPITUDE.

In violation of the Anti-Fencing Law, actual knowledge by the fence of the fact that

property received is stolen displays the same degree of malicious deprivation of ones

rightful property as that which animated the robbery or theft which by their very nature

are crimes of moral turpitude. (Dela Torre v. COMELEC 07/05/96)

Moral turpitude can be derived from the third element accused knows or should have

known that the items were stolen. Participation of each felon, one being the robber or the

thief or the actual perpetrators, and the other as the fence, differs in point in time and

degree but both invaded ones peaceful dominion for gain. (Supra) Both crimes negated the

principle of each persons duty to his fellowmen not to appropriate things that they do not

own or return something acquired by mistake or with malice. This signifies moral

turpitude with moral unfitness.

In the case of Dela Torre, he was declared disqualified from running the position of Mayor

in Cavinti, Laguna in the last May 8, 1995 elections because of the fact of the

disqualification under Sec. 40 of the Local Government Code, of persons running for

elective position -Sec. 40 Disqualifications (a) Those sentenced by final judgement for an

offense involving moral turpitude

Dela Torre was disqualified because of his prior conviction of the crime of fencing wherein

he admitted all the elements of the crime of fencing.

ESSENCE OF VIOLATION OF PD 1612, SEC. 2 OR ANTI-FENCING

PD 1612, Section 2 thereof requires that the offender buys or otherwise acquires and then

sells or disposes of any object of value which he knows or should he known to him to have

been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft. (Caoili v CA; GR 128369,

12/22/97)

PROOF OF PURCHASE WHEN GOODS ARE IN POSSESSION OF OFFENDER NOT NECESSARY

IN ANTI-FENCING

The law does not require proof of purchase of the stolen articles by petitioner, as mere

possession thereof is enough to give rise to a presumption of fencing.

It was incumbent upon petitioner to overthrow this presumption by sufficient and

convincing evidence. (Caoili v. CA; GR 128369, 12/22/97)

MALACAANG

M a n i l a

PRESIDENTIAL DECREE No. 1612

ANTI-FENCING LAW OF 1979

WHEREAS, reports from law enforcement agencies reveal that there is rampant robbery

and thievery of government and private properties;

WHEREAS, such robbery and thievery have become profitable on the part of the lawless

elements because of the existence of ready buyers, commonly known as fence, of stolen

properties;

WHEREAS, under existing law, a fence can be prosecuted only as an accessory after the

fact and punished lightly;

WHEREAS, is imperative to impose heavy penalties on persons who profit by the effects of

the crimes of robbery and theft.

NOW, THEREFORE, I, FERDINAND E. MARCOS, President of the Philippines by virtue of the

powers vested in me by the Constitution, do hereby order and decree as part of the law of

the land the following:

Section 1. Title. This decree shall be known as the Anti-Fencing Law.

Sec. 2. Definition of Terms. The following terms shall mean as follows:

(a) "Fencing" is the act of any person who, with intent to gain for himself or for another,

shall buy, receive, possess, keep, acquire, conceal, sell or dispose of, or shall buy and sell, or

in any other manner deal in any article, item, object or anything of value which he knows,

or should be known to him, to have been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery

or theft.

(b) "Fence" includes any person, firm, association corporation or partnership or other

organization who/which commits the act of fencing.

Sec. 3. Penalties. Any person guilty of fencing shall be punished as hereunder indicated:

(a) The penalty of prision mayor, if the value of the property involved is more than 12,000

pesos but not exceeding 22,000 pesos; if the value of such property exceeds the latter sum,

the penalty provided in this paragraph shall be imposed in its maximum period, adding one

year for each additional 10,000 pesos; but thetotal penalty which may be imposed shall not

exceed twenty years. In such cases, the penalty shall be termed reclusion temporal and the

accessory penalty pertaining thereto provided in the Revised Penal Code shall also be

imposed.

(b) The penalty of prision correccional in its medium and maximum periods, if the value of

the property robbed or stolen is more than 6,000 pesos but not exceeding 12,000 pesos.

(c) The penalty of prision correccional in its minimum and medium periods, if the value of

the property involved is more than 200 pesos but not exceeding 6,000 pesos.

(d) The penalty of arresto mayor in its medium period to prision correccional in its

minimum period, if the value of the property involved is over 50 pesos but not exceeding

200 pesos.

(e) The penalty of arresto mayor in its medium period if such value is over five (5) pesos

but not exceeding 50 pesos.

(f) The penalty of arresto mayor in its minimum period if such value does not exceed 5

pesos.

Sec. 4. Liability of Officials of Juridical Persons. If the fence is a partnership, firm,

corporation or association, the president or the manager or any officer thereof who knows

or should have known the commission of the offense shall be liable.

Sec. 5. Presumption of Fencing. Mere possession of any good, article, item, object, or

anything of value which has been the subject of robbery or thievery shall be prima

facie evidence of fencing.

Sec. 6. Clearance/Permit to Sell/Used Second Hand Articles. For purposes of this Act, all

stores, establishments or entities dealing in the buy and sell of any good, article item, object

of anything of value obtained from an unlicensed dealer or supplier thereof, shall before

offering the same for sale to the public, secure the necessary clearance or permit from the

station commander of the Integrated National Police in the town or city where such store,

establishment or entity is located. The Chief of Constabulary/Director General, Integrated

National Police shall promulgate such rules and regulations to carry out the provisions of

this section. Any person who fails to secure the clearance or permit required by this section

or who violates any of the provisions of the rules and regulations promulgated thereunder

shall upon conviction be punished as a fence.

Sec. 7. Repealing Clause. All laws or parts thereof, which are inconsistent with the

provisions of this Decree are hereby repealed or modified accordingly.

Sec. 8. Effectivity. This Decree shall take effect upon approval.

Done in the City of Manila, this 2nd day of March, in the year of Our Lord, nineteen hundred

and seventy-nine.

RULES AND REGULATIONS TO CARRY OUT THE PROVISIONS OF Sec. 6 OF PRESIDENTIAL

DECREE NO. 1612, KNOWN AS THE ANTI-FENCING LAW.

Pursuant to Sec. 6 of Presidential Decree No. 1612, known as the Anti-Fencing Law, the

following rules and regulations are hereby promulgated to govern the issuance of

clearances/permits to sell used secondhand articles obtained from an unlicensed dealer or

supplier thereof:

I. Definition of Terms

1. "Used secondhand article" shall refer to any goods, article, item, object or anything of

value obtained from an unlicensed dealer or supplier, regardless of whether the same has

actually or in fact been used.

2. "Unlicensed dealer/supplier" shall refer to any persons, partnership, firm, corporation,

association or any other entity or establishment not licensed by the government to engage

in the business of dealing in or of supplying the articles defined in the preceding paragraph.

3. "Store", "establishment" or "entity" shall be construed to include any individual dealing

in the buying and selling used secondhand articles, as defined in paragraph hereof.

4. "Buy and Sell" refer to the transaction whereby one purchases used secondhand articles

for the purpose of resale to third persons.

5. "Station Commander" shall refer to the Station Commander of the Integrated National

Police within the territorial limits of the town or city district where the store,

establishment or entity dealing in the buying and selling of used secondhand articles is

located.

II. Duty to Procure Clearance or Permit

1. No person shall sell or offer to sell to the public any used secondhand article as defined

herein without first securing a clearance or permit for the purpose from the proper Station

Commander of the Integrated National Police.

2. If the person seeking the clearance or permit is a partnership, firm, corporation, or

association or group of individuals, the clearance or permit shall be obtained by or in the

name of the president, manager or other responsible officer-in-charge thereof.

3. If a store, firm, corporation, partnership, association or other establishment or entity has

a branch or subsidiary and the used secondhand article is acquired by such branch or

subsidiary for sale to the public, the said branch or subsidiary shall secure the required

clearance or permit.

4. Any goods, article, item, or object or anything of value acquired from any source for

which no receipt or equivalent document evidencing the legality of its acquisition could be

presented by the present possessor or holder thereof, or the covering receipt, or equivalent

document, of which is fake, falsified or irregularly obtained, shall be presumed as having

been acquired from an unlicensed dealer or supplier and the possessor or holder thereof

must secure the required clearance or permit before the same can be sold or offered for

sale to the public.

III. Procedure for Procurement of Clearances or Permits

1. The Station Commanders concerned shall require the owner of a store or the president,

manager or responsible officer-in-charge of a firm, establishment or other entity located

within their respective jurisdictions and in possession of or having in stock used

secondhand articles as defined herein, to submit an initial affidavit within thirty (30) days

from receipt of notice for the purpose thereof and subsequent affidavits once every fifteen

(15) days within five (5) days after the period covered, which shall contain:

(a) A complete inventory of such articles acquired daily from whatever source and the

names and addresses of the persons from whom such articles were acquired.

(b) A full list of articles to be sold or offered for sale as well as the place where the date

when the sale or offer for sale shall commence.

(c) The place where the articles are presently deposited or kept in stock.

The Station Commander may, at his discretion when the circumstances of each case

warrant, require that the affidavit submitted be accompanied by other documents showing

proof of legitimacy of the acquisition of the articles.

2. A party required to secure a clearance or permit under these rules and regulations shall

file an application therefor with the Station Commander concerned. The application shall

state:

(a) The name, address and other pertinent circumstances of the persons, in case of an

individual or, in the case of a firm, corporation, association, partnership or other entity, the

name, address and other pertinent circumstances of the president, manager or officer-in-

charge.

(b) The article to be sold or offered for sale to the public and the name and address of the

unlicensed dealer or supplier from whom such article was acquired.

In support of the application, there shall be attached to it the corresponding receipt or

other equivalent document to show proof of the legitimacy of acquisition of the article.

3. The Station Commander shall examine the documents attached to the application and

may require the presentation of other additional documents, if necessary, to show

satisfactory proof of the legitimacy of acquisition of the article, subject to the following

conditions:

(a) If the legitimacy of acquisition of any article from an unlicensed source cannot be

satisfactorily established by the documents presented, the Station Commander shall, upon

approval of the INP Superintendent in the district and at the expense of the party seeking

the clearance/permit, cause the publication of a notice in a newspaper of general

circulation for two (2) successive days enumerating therein the articles acquired from an

unlicensed dealer or supplier, the names and addresses of the persons from whom they

were acquired and shall state that such articles are to be sold or offered for sale to the

public at the address of the store, establishment or other entity seeking the

clearance/permit. In places where no newspapers are in general circulation, the party

seeking the clearance or permit shall, instead, post a notice daily for one week on the

bulletin board of the municipal building of the town where the store, firm, establishment or

entity concerned is located or, in the case of an individual, where the articles in his

possession are to be sold or offered for sale.

(b) If after 15 days, upon expiration of the period of publication or of the notice referred to

in the preceding paragraph, no claim is made with respect to any of the articles enumerated

in the notice, the Station Commander shall issue the clearance or permit sought.

(c) If, before expiration of the same period for publication of the notice or its posting, it

shall appear that any of the articles in question is stolen property, the Station Commander

shall hold the article in restraint as evidence in any appropriate case to be filed. Articles

held in restraint shall be kept and disposed of as the circumstances of each case permit,

taking into account all considerations of right and justice in the case. In any case where any

article is held in restraint, it shall be the duty of the Station Commander concerned to

advise/notify the Commission on Audit of the case and comply with such procedure as may

be proper under applicable existing laws, rules and regulations.

4. The Station Commander concerned shall, within seventy-two (72) hours from receipt of

the application, act thereon by either issuing the clearance/permit requested or denying

the same. Denial of an application shall be in writing and shall state in brief the reason/s

therefor.

5. The application, clearance/permit or the denial thereof, including such other documents

as may be pertinent in the implementation of Sec. 6 of P.D. No. 1612 shall be in the forms

prescribed in Annexes "A", "B", "C", "D", and "E" hereof, which are made integral parts of

these rules and regulations.

6. For the issuance of clearances/permit required under Sec. 6 of P.D. No. 1612, no fee shall

be charged.

IV. Appeals

Any party aggrieved by the action taken by the Station Commander may elevate the

decision taken in the case to the proper INP District Superintendent and, if he is still

dissatisfied therewith may take the same on appeal to the INP Director. The decision of the

INP Director may also be appealed to the INP Director-General whose decision may

likewise be appealed to the Minister of National Defense. The decision of the Minister of

National Defense on the case shall be final. The appeal against the decision taken by a

Commander lower than the INP Director-General should be filed to the next higher

Commander within ten (10) days from receipt of notice of the decision. The decision of the

INP Director-General should be appealed within fifteen (15) days from receipt of notice of

the decision.

V. Penalties

1. Any person who fails to secure the clearance or permit required by Sec. 6 of P.D. 1612 or

who violates any of the provisions of these rules and regulations shall upon conviction be

punished as a fence.

2. The INP Director-General shall recommend to the proper authority the cancellation of

the business license of the erring individual, store, establishment or the entity concerned.

3. Articles obtained from unlicensed sources for sale or offered for sale without prior

compliance with the provisions of Sec. 6 of P.D. No. 1612 and with these rules and

regulations shall be held in restraint until satisfactory evidence or legitimacy of acquisition

has been established.

4. Articles for which no satisfactory evidence of legitimacy of acquisition is established and

which are found to be stolen property shall likewise be held under restraint and shall,

furthermore, be subject to confiscation as evidence in the appropriate case to be filed. If,

upon termination of the case, the same is not claimed by their legitimate owners, the

article/s shall be forfeited in favor of the government and made subject to disposition as

the circumstances warrant in accordance with applicable existing laws, rules and

regulations. The Commission on Audit shall, in all cases, be notified.

5. Any personnel of the Integrated National Police found violating the provisions of Sec. 6 of

P.D. No. 1612 or any of its implementing rules and regulations or who, in any manner

whatsoever, connives with or through his negligence or inaction makes possible the

commission of such violations by any party required to comply with the law and its

implementing rules and regulations, shall be prosecuted criminally without prejudice to

the imposition of administrative penalties.

VI. Visitorial Power

It shall be the duty of the owner of the store or of the president, manager or responsible

officer-in-charge of any firm, establishment or other entity or of an individual having in his

premises articles to be sold or offered for sale to the public to allow the Station Commander

or his authorized representative to exercise visitorial powers. For this purpose, however,

the power to conduct visitations shall be exercise only during office or business hours and

upon authority in writing from and by the INP Superintendent in the district and for the

sole purpose of determining whether articles are kept in possession or stock contrary to

the intents of Sec. 6 of P.D. No. 1612 and of these rules and regulations.

VII. Other Duties Imposed Upon Station Commanders and INP District Superintendent and

Directors Following Action on Applications for Clearances or Permits

1. At the end of each month, it shall be the duty of the Station Commander concerned to:

(a) Make and maintain a file in his office of all clearances/permit issued by him.

(b) Submit a full report to the INP District Superintendent on the number of applications

for clearances or permits processed by his office, indicating therein the number of

clearances/permits issued and the number of applications denied. The report shall state

the reasons for denial of an application and the corresponding follow-up actions taken and

shall be accompanied by an inventory of the articles to be sold or offered for sale in his

jurisdiction.

2. The INP District Superintendent shall, on the basis of the reports submitted by the

Station Commander, in turn submit quarterly reports to the appropriate INP Director

containing a consolidation of the information stated in the reports of Station Commanders

in his jurisdiction.

3. Reports from INP District Superintendent shall serve as basis for a consolidated report to

be submitted semi-annually by INP Directors to the Director-General, Integrated National

Police.

4. In all cases, reports emanating from the different levels of the Integrated National Police

shall be accompanied with full and accurate inventories of the articles acquired from

unlicensed dealers or suppliers and proposed to be sold or offered for sale in the

jurisdictions covered by the report.

These implementing rules and regulations, having been published in a newspaper of

national circulation, shall take effect on June 15, 1979.

FOR THE CHIEF OF CONSTABULARY DIRECTOR-GENERAL, INP:

FIRST DIVISION

[G.R. No. 134298. August 26, 1999]

RAMON C. TAN, petitioner, vs. PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, respondent.

D E C I S I O N

PARDO, J.:

The case before the Court is an appeal via certiorari from a decision of the Court of

Appeals* affirming that of the Regional Trial Court of Manila, Branch 19,** convicting

petitioner of the crime of fencing.

Complainant Rosita Lim is the proprietor of Bueno Metal Industries, located at 301 Jose

Abad Santos St., Tondo, Manila, engaged in the business of manufacturing propellers or

spare parts for boats. Manuelito Mendez was one of the employees working for her.

Sometime in February 1991, Manuelito Mendez left the employ of the company.

Complainant Lim noticed that some of the welding rods, propellers and boat spare parts,

such as bronze and stainless propellers andbrass screws were missing. She conducted an

inventory and discovered that propellers and stocks valued at P48,000.00, more or less,

were missing. Complainant Rosita Lim informed Victor Sy, uncle of Manuelito Mendez, of

the loss. Subsequently, Manuelito Mendez was arrested in the Visayas and he admitted that

he and his companion Gaudencio Dayop stole from the complainants warehouse some boat

spare parts such as bronze and stainless propellers and brass screws. Manuelito Mendez

asked for complainants forgiveness. He pointed to petitioner Ramon C. Tan as the one who

bought the stolen items and who paid the amount of P13,000.00, in cash to Mendez and

Dayop, and they split the amount with one another. Complainant did not file a case against

Manuelito Mendez and Gaudencio Dayop.

On relation of complainant Lim, an Assistant City Prosecutor of Manila filed with the

Regional Trial Court, Manila, Branch 19, an information against petitioner charging him

with violation of Presidential Decree No. 1612 (Anti-Fencing Law) committed as follows:

That on or about the last week of February 1991, in the City of Manila, Philippines, the

said accused, did then and there wilfully, unlawfully and feloniously knowingly receive,

keep, acquire and possess several spare parts and items for fishing boats all valued at

P48,130.00 belonging to Rosita Lim, which he knew or should have known to have been

derived from the proceeds of the crime of theft.

Contrary to law.

Upon arraignment on November 23, 1992, petitioner Ramon C. Tan pleaded not guilty to

the crime charged and waived pre-trial. To prove the accusation, the

prosecution presented the testimonies of complainant Rosita Lim, Victor Sy and the

confessed thief, Manuelito Mendez.

On the other hand, the defense presented Rosita Lim and Manuelito Mendez as hostile

witnesses and petitioner himself. The testimonies of the witnesses were summarized by

the trial court in its decision, as follows:

ROSITA LIM stated that she is the owner of Bueno Metal Industries, engaged in

the business of manufacturing propellers, bushings, welding rods, among others (Exhibits

A, A-1, and B). That sometime in February 1991, after one of her employees left the

company, she discovered that some of the manufactured spare parts were missing, so that

on February 19, 1991, an inventory was conducted and it was found that some welding

rods and propellers, among others, worth P48,000.00 were missing. Thereafter, she went

to Victor Sy, the person who recommended Mr. Mendez to her. Subsequently, Mr. Mendez

was arrested in the Visayas, and upon arrival in Manila, admitted to his having stolen the

missing spare parts sold then to Ramon Tan. She then talked to Mr. Tan, who denied

having bought the same.

When presented on rebuttal, she stated that some of their stocks were bought under the

name of Asia Pacific, the guarantor of their Industrial Welding Corporation, and stated

further that whether the stocks are bought under the name of the said corporation or

under the name of William Tan, her husband, all of these items were actually delivered to

the store at 3012-3014 Jose Abad Santos Street and all paid by her husband.

That for about one (1) year, there existed a business relationship between her husband and

Mr. Tan. Mr. Tan used to buy from them stocks of propellers while they likewise bought

from the former brass woods, and that there is no reason whatsoever why she has to frame

up Mr. Tan.

MANUELITO MENDEZ stated that he worked as helper at Bueno Metal Industries from

November 1990 up to February 1991. That sometime in the third week of February 1991,

together with Gaudencio Dayop, his co-employee, they took from the warehouse of Rosita

Lim some boat spare parts, such as bronze andstainless propellers, brass screws, etc. They

delivered said stolen items to Ramon Tan, who paid for them in cash in the amount of

P13,000.00. After taking his share (one-half (1/2) of the amount), he went home directly to

the province. When he received a letter from his uncle, Victor Sy, he decided to return to

Manila. He was then accompanied by his uncle to see Mrs. Lim, from whom he begged for

forgiveness on April 8, 1991. On April 12, 1991, he executed an affidavit prepared by a

certain Perlas, a CIS personnel, subscribed to before a Notary Public (Exhibits C and C-1).

VICTORY [sic] SY stated that he knows both Manuelito Mendez and Mrs. Rosita Lim, the

former being the nephew of his wife while the latter is his auntie. That sometime in

February 1991, his auntie called up and informed him about the spare parts stolen from the

warehouse by Manuelito Mendez. So that he sent his son to Cebu and requested his

kumpadre, a police officer of Sta. Catalina, Negros Occidental, to arrest and bring Mendez

back to Manila. When Mr. Mendez was brought to Manila, together with Supt. Perlas of the

WPDC, they fetched Mr. Mendez from the pier after which they proceeded to the house of

his auntie. Mr. Mendez admitted to him having stolen the missing items and sold to Mr.

Ramon Tan in Sta. Cruz, Manila. Again, he brought Mr. Mendez to Sta. Cruz where he

pointed to Mr. Tan as the buyer, but when confronted, Mr. Tan denied the same.

ROSITA LIM, when called to testify as a hostile witness, narrated that she owns Bueno

Metal Industries located at 301 Jose Abad Santos Street, Tondo, Manila. That two (2) days

after Manuelito Mendez and Gaudencio Dayop left, her husband, William Tan, conducted an

inventory and discovered that some of the spare parts worth P48,000.00 were missing.

Some of the missing items were under the name of Asia Pacific and William Tan.

MANUELITO MENDEZ, likewise, when called to testify as a hostile witness, stated that he

received a subpoena in the Visayas from the wife of Victor Sy, accompanied by a policeman

of Buliloan, Cebu on April 8, 1991. That he consented to come to Manila to

ask forgiveness from Rosita Lim. That in connection with this case, he executed an affidavit

on April 12, 1991, prepared by a certain Atty. Perlas, a CIS personnel, and the contents

thereof were explained to him by Rosita Lim before he signed the same before Atty. Jose

Tayo, a Notary Public, at Magnolia House, Carriedo, Manila (Exhibits C and C-1).

That usually, it was the secretary of Mr. Tan who accepted the items delivered to Ramon

Hardware. Further, he stated that the stolen items from the warehouse were placed in a

sack and he talked to Mr. Tan first over the phone before he delivered the spare parts. It

was Mr. Tan himself who accepted the stolen items in the morning at about 7:00 to 8:00

oclock and paid P13,000.00 for them.

RAMON TAN, the accused, in exculpation, stated that he is a businessman engaged in selling

hardware (marine spare parts) at 944 Espeleta Street, Sta. Cruz, Manila.

He denied having bought the stolen spare parts worth P48,000.00 for he never talked nor

met Manuelito Mendez, the confessed thief. That further the two (2) receipts presented by

Mrs. Lim are not under her name and the other two (2) are under the name of William Tan,

the husband, all in all amounting to P18,000.00. Besides, the incident was not reported to

the police (Exhibits 1 to 1-g).

He likewise denied having talked to Manuelito Mendez over the phone on the day of the

delivery of the stolen items and could not have accepted the said items personally for

everytime (sic) goods are delivered to his store, the same are being accepted by his staff. It

is not possible for him to be at his office at about 7:00 to 8:00 oclock in the morning,

because he usually reported to his office at 9:00 oclock. In connection with this case, he

executed a counter-affidavit (Exhibits 2 and 2-a).[1]

On August 5, 1996, the trial court rendered decision, the dispositive portion of which reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the accused RAMON C. TAN is hereby found guilty

beyond reasonable doubt of violating the Anti-Fencing Law of 1979, otherwise known as

Presidential Decree No. 1612, and sentences him to suffer the penalty of imprisonment of

SIX (6) YEARS and ONE (1) DAY to TEN (10) YEARS of prision mayor and to indemnify

Rosita Lim the value of the stolen merchandise purchased by him in the sum of P18,000.00.

Costs against the accused.

SO ORDERED.

Manila, Philippines, August 5, 1996.

(s/t) ZENAIDA R. DAGUNA

Judge

Petitioner appealed to the Court of Appeals.

After due proceedings, on January 29, 1998, the Court of Appeals rendered decision finding

no error in the judgment appealed from, and affirming the same intoto.

In due time, petitioner filed with the Court of Appeals a motion for reconsideration;

however, on June 16, 1998, the Court of Appeals denied the motion.

Hence, this petition.

The issue raised is whether or not the prosecution has successfully established the

elements of fencing as against petitioner.[2]

We resolve the issue in favor of petitioner.

Fencing, as defined in Section 2 of P.D. No. 1612 is the act of any person who, with intent

to gain for himself or for another, shall buy, receive, possess, keep, acquire, conceal, sell or

dispose of, or shall buy and sell, or in any manner deal in any article, item, object or

anything of value which he knows, or should be known to him, to have been derived from

the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft.[3]

Robbery is the taking of personal property belonging to another, with intent to gain, by

means of violence against or intimidation of any person, or using force upon things.[4]

The crime of theft is committed if the taking is without violence against or intimidation of

persons nor force upon things.[5]

The law on fencing does not require the accused to have participated in the criminal

design to commit, or to have been in any wise involved in the commission of, the crime of

robbery or theft.[6]

Before the enactment of P. D. No. 1612 in 1979, the fence could only be prosecuted as an

accessory after the fact of robbery or theft, as the term is defined in Article 19 of the

Revised Penal Code, but the penalty was light as it was two (2) degrees lower than that

prescribed for the principal.[7]

P. D. No. 1612 was enacted to impose heavy penalties on persons who profit by the effects

of the crimes of robbery and theft. Evidently, the accessory in the crimes of robbery and

theft could be prosecuted as such under the Revised Penal Code or under P.D. No. 1612.

However, in the latter case, the accused ceases to be a mere accessory but becomes a

principal in the crime of fencing. Otherwise stated, the crimes of robbery and theft, on the

one hand, and fencing, on the other, are separate and distinct offenses.[8] The State may

thus choose to prosecute him either under the Revised Penal Code or P. D. No. 1612,

although the preference for the latter would seem inevitable considering that fencing

is malum prohibitum, and P. D. No. 1612 creates a presumption of fencing[9] and

prescribes a higher penalty based on the value of the property.[10]

In Dizon-Pamintuan vs. People of the Philippines, we set out the essential elements of the

crime of fencing as follows:

1. A crime of robbery or theft has been committed;

2. The accused, who is not a principal or accomplice in the commission of the crime of

robbery or theft, buys, receives, possesses, keeps, acquires, conceals, sells or disposes, or

buys and sells, or in any manner deals in any article, item, object or anything of value,

which has been derived from the proceeds of the said crime;

3. The accused knows or should have known that the said article, item, object or anything

of value has been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft; and

4. There is on the part of the accused, intent to gain for himself or for another.[11]

Consequently, the prosecution must prove the guilt of the accused by establishing the

existence of all the elements of the crime charged. [12]

Short of evidence establishing beyond reasonable doubt the existence of the essential

elements of fencing, there can be no conviction for such offense.[13] It is an ancient

principle of our penal system that no one shall be found guilty of crime except upon proof

beyond reasonable doubt (Perez vs. Sandiganbayan, 180 SCRA 9).[14]

In this case, what was the evidence of the commission of theft independently of fencing?

Complainant Rosita Lim testified that she lost certain items and Manuelito Mendez

confessed that he stole those items and sold them to the accused. However, Rosita Lim

never reported the theft or even loss to the police. She admitted that after Manuelito

Mendez, her former employee, confessed to the unlawful taking of the items, she forgave

him, and did not prosecute him. Theft is a public crime. It can be prosecuted de oficio, or

even without a private complainant, but it cannot be without a victim. As complainant

Rosita Lim reported no loss, we cannot hold for certain that there was committed a

crime of theft. Thus, the first element of the crime of fencing is absent, that is, a

crime of robbery or theft has been committed.

There was no sufficient proof of the unlawful taking of anothers property. True, witness

Mendez admitted in an extra-judicial confession that he sold the boat parts he had pilfered

from complainant to petitioner. However, an admission or confession acknowledging guilt

of an offense may be given in evidence only against the person admitting or

confessing.[15] Even on this, if given extra-judicially, the confessant must have the

assistance of counsel; otherwise, the admission would be inadmissible in evidence against

the person so admitting.[16] Here, the extra-judicial confession of witness Mendez was not

given with the assistance of counsel, hence, inadmissible against the witness. Neither may

such extra-judicial confession be considered evidence against accused.[17] There must be

corroboration by evidence of corpus delicti to sustain a finding of guilt.[18] Corpus

delicti means the body or substance of the crime, and, in its primary sense, refers to the

fact that the crime has been actually committed.[19] The essential elements of theft are

(1) the taking of personal property; (2) the property belongs to another; (3) the taking

away was done with intent of gain; (4) the taking away was done without the consent of the

owner; and (5) the taking away is accomplished without violence or intimidation against

persons or force upon things (U. S. vs. De Vera, 43 Phil. 1000).[20] In theft, corpus

delicti has two elements, namely: (1) that the property was lost by the owner, and (2) that

it was lost by felonious taking.[21] In this case, the theft was not proved because

complainant Rosita Lim did not complain to the public authorities of the felonious taking of

her property. She sought out her former employee Manuelito Mendez, who confessed that

he stole certain articles from the warehouse of the complainant and sold them to

petitioner. Such confession is insufficient to convict, without evidence of corpus delicti.[22]

What is more, there was no showing at all that the accused knew or should have known

that the very stolen articles were the ones sold to him. One is deemed to know a particular

fact if he has the cognizance, consciousness or awareness thereof, or is aware of the

existence of something, or has the acquaintance with facts, or if he has something within

the minds grasp with certitude and clarity. When knowledge of the existence of a

particular fact is an element of an offense, such knowledge is established if a person is

aware of a high probability of its existence unless he actually believes that it does not exist.

On the other hand, the words should know denote the fact that a person of reasonable

prudence and intelligence would ascertain the fact in performance of his duty to another or

would govern his conduct upon assumption that such fact exists. Knowledge refers to a

mental state of awareness about a fact. Since the court cannot penetrate the mind of an

accused and state with certainty what is contained therein, it must determine such

knowledge with care from the overt acts of that person. And given two equally plausible

states of cognition or mental awareness, the court should choose the one which sustains

the constitutional presumption of innocence.[23]

Without petitioner knowing that he acquired stolen articles, he can not be guilty of

fencing.[24]

Consequently, the prosecution has failed to establish the essential elements of fencing, and

thus petitioner is entitled to an acquittal.

WHEREFORE, the Court REVERSES and SETS ASIDE the decision of the Court of Appeals in

CA-G.R. CR. No. 20059 and hereby ACQUITS petitioner of the offense charged in Criminal

Case No. 92-108222 of the Regional Trial Court, Manila.

Costs de oficio.

SO ORDERED.

Davide, Jr., C.J., (Chairman), Puno, Kapunan, and Ynares-Santiago, JJ., concur.

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

G.R. No. 190475 April 10, 2013

JAIME ONG y ONG, Petitioner,

vs.

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Respondent.

D E C I S I O N

SERENO, CJ.:

Before the Court is an appeal from the Decision1 dated 18 August 2009 of the Court of

Appeals (CA), which affirmed the Decision2 dated 06 January 2006 of the Regional Trial

Court (RTC), Branch 37, Manila. The RTC had convicted accused Jaime Ong y Ong (Ong) of

the crime of violation of Presidential Decree No. (P.O.) 1612, otherwise known as. the Anti-

Fencing Law.

Ong was charged in an Information3 dated 25 May 1995 as follows:

That on or about February 17, 1995, in the City of Manila, Philippines. the said accused,

with intent of gain for himself or for another. did then and there willfully, unlawfully and

feloniously receive and acquire from unknown person involving thirteen (13) truck tires

worth P65, 975.00, belonging to FRANCISCO AZAJAR Y LEE, and thereafter selling One

(1) truck tire knowing the same to have been derived from the crime of robbery.

CONTRARY TO LAW.

Upon arraignment, Ong entered a plea of "not guilty." Trial on the merits ensued, and the

RTC found him guilty beyond reasonable doubt of violation of P.D. 1612. The dispositive

portion of its Decision reads:

WHEREFORE, premises considered, this Court finds that the prosecution has established

the guilt of the accused JAIME ONG y ONG beyond reasonable doubt for violation of

Presidential Decree No. 1612 also known as Anti-Fencing Law and is hereby sentenced to

suffer the penalty of imprisonment of 10 years and 1 day to 16 years with accessory

penalty of temporary disqualification.

SO ORDERED.4

Dissatisfied with the judgment, Ong appealed to the CA. After a review of the records, the

RTCs finding of guilt was affirmed by the appellate court in a Decision dated 18 August

2009.

Ong then filed the instant appeal before this Court.

The Facts

The version of the prosecution, which was supported by the CA, is as follows:

Private complainant was the owner of forty-four (44) Firestone truck tires, described as

T494 1100 by 20 by 14. He acquired the same for the total amount of P223,401.81 from

Philtread Tire and Rubber Corporation, a domestic corporation engaged in the

manufacturing and marketing of Firestone tires. Private complainant's acquisition was

evidenced by Sales Invoice No. 4565 dated November 10, 1994 and an Inventory List

acknowledging receipt of the tires specifically described by their serial numbers. Private

complainant marked the tires using a piece of chalk before storing them inside the

warehouse in 720 San Jose St., corner Sta. Catalina St., Barangay San Antonio Valley 1,

Sucat, Paraaque, owned by his relative Teody Guano. Jose Cabal, Guano's caretaker of the

warehouse, was in charge of the tires. After appellant sold six (6) tires sometime in January

1995, thirty-eight (38) tires remained inside the warehouse.

On February 17, 1995, private complainant learned from caretaker Jose Cabal that all

thirty-eight (38) truck tires were stolen from the warehouse, the gate of which was forcibly

opened. Private complainant, together with caretaker Cabal, reported the robbery to the

Southern Police District at Fort Bonifacio.

Pending the police investigation, private complainant canvassed from numerous business

establishments in an attempt to locate the stolen tires. On February 24, 1995, private

complainant chanced upon Jong's Marketing, a store selling tires in Paco, Manila, owned

and operated by appellant. Private complainant inquired if appellant was selling any Model

T494 1100 by 20 by 14 ply Firestone tires, to which the latter replied in the affirmative.

Appellant brought out a tire fitting the description, which private complainant recognized

as one of the tires stolen from his warehouse, based on the chalk marking and the serial

number thereon. Private complainant asked appellant if he had any more of such tires in

stock, which was again answered in the affirmative. Private complainant then left the store

and reported the matter to Chief Inspector Mariano Fegarido of the Southern Police

District.

On February 27, 1995, the Southern Police District formed a team to conduct a buy-bust

operation on appellant'sstore in Paco, Manila. The team was composed of six (6) members,

led by SPO3 Oscar Guerrero and supervised by Senior Inspector Noel Tan. Private

complainant's companion Tito Atienza was appointed as the poseur-buyer.

On that same day of February 27, 1995, the buy-bust team, in coordination with the

Western Police District, proceeded to appellant's store in Paco, Manila. The team arrived

thereat at around 3:00 in the afternoon. Poseur-buyer Tito Atienza proceeded to the store

while the rest of the team posted themselves across the street. Atienza asked appellant if he

had any T494 1100 by 20 by 14 Firestone truck tires available. The latter immediately

produced one tire from his display, which Atienza bought for P5,000.00. Atienza asked

appellant if he had any more in stock.

Appellant then instructed his helpers to bring out twelve (12) more tires from his

warehouse, which was located beside his store. After the twelve (12) truck tires were

brought in, private complainant entered the store, inspected them and found that they

were the same tires which were stolen from him, based on their serial numbers. Private

complainant then gave the prearranged signal to the buy-bust team confirming that the

tires in appellant's shop were the same tires stolen from the warehouse.

After seeing private complainant give the pre-arranged signal, the buy-bust team went

inside appellant's store. However, appellant insisted that his arrest and the confiscation of

the stolen truck tires be witnessed by representatives from the barangay and his own

lawyer. Resultantly, it was already past 10:00 in the evening when appellant, together with

the tires, was brought to the police station for investigation and inventory. Overall, the buy-

bust team was able to confiscate thirteen (13) tires, including the one initially bought by

poseur-buyer Tito Atienza. The tires were confirmed by private complainant as stolen from

his warehouse.5

For his part, accused Ong solely testified in his defense, alleging that he had been engaged

in the business of buying and selling tires for twenty-four (24) years and denying that he

had any knowledge that he was selling stolen tires in Jong Marketing. He further averred

that on 18 February 1995, a certain Ramon Go (Go) offered to sell thirteen (13) Firestone

truck tires allegedly from Dagat-dagatan, Caloocan City, for P3,500 each. Ong bought all the

tires for P45,500, for which he was issued a Sales Invoice dated 18 February 1995 and with

the letterhead Gold Link Hardware & General Merchandise (Gold Link).6

Ong displayed one (1) of the tires in his store and kept all the twelve (12) others in his

bodega. The poseur-buyer bought the displayed tire in his store and came back to ask for

more tires. Ten minutes later, policemen went inside the store, confiscated the tires,

arrested Ong and told him that those items were stolen tires.7

The RTC found that the prosecution had sufficiently established that all thirteen (13) tires

found in the possession of Ong constituted a prima facie evidence of fencing. Having failed

to overcome the presumption by mere denials, he was found guilty beyond reasonable

doubt of violation of P.D. 1612.8

On appeal, the CA affirmed the RTCs findings with modification by reducing the minimum

penalty from ten (10) years and one (1) day to six (6) years of prision correcional.9

OUR RULING

The Petition has no merit.

Fencing is defined in Section 2(a) of P.D. 1612 as the "act of any person who, with intent to

gain for himself or for another, shall buy, receive, possess, keep, acquire, conceal, sell or

dispose of, or shall buy and sell, or in any manner deal in any article, item, object or

anything of value which he knows, or should be known to him, to have been derived from

the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft."

The essential elements of the crime of fencing are as follows: (1) a crime of robbery or theft

has been committed; (2) the accused, who is not a principal or on accomplice in the

commission of the crime of robbery or theft, buys, receives, possesses, keeps, acquires,

conceals, sells or disposes, or buys and sells, or in any manner deals in any article, item,

object or anything of value, which has been derived from the proceeds of the crime of

robbery or theft; (3) the accused knew or should have known that the said article, item,

object or anything of value has been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery or

theft; and (4) there is, on the part of one accused, intent to gain for oneself or for

another.10

We agree with the RTC and the CA that the prosecution has met the requisite quantum of

evidence in proving that all the elements of fencing are present in this case.

First, the owner of the tires, private complainant Francisco Azajar (Azajar), whose

testimony was corroborated by Jose Cabal - the caretaker of the warehouse where

the thirty-eight (38) tires were stolen testified that the crime of robbery had been

committed on 17 February 1995. Azajar was able to prove ownership of the tires

through Sales Invoice No. 456511 dated 10 November 1994 and an Inventory

List.12 Witnesses for the prosecution likewise testified that robbery was reported as

evidenced by their Sinumpaang Salaysay13 taken at the Southern Police District at

Fort Bonifacio.14 The report led to the conduct of a buy-bust operation at Jong

Markerting, Paco, Manila on 27 February 1995.

Second, although there was no evidence to link Ong as the perpetrator of the robbery, he

never denied the fact that thirteen (13) tires of Azajar were caught in his possession. The

facts do not establish that Ong was neither a principal nor an accomplice in the crime of

robbery, but thirteen (13) out of thirty-eight (38) missing tires were found in his

possession. This Court finds that the serial numbers of stolen tires corresponds to those

found in Ongs possession.15 Ong likewise admitted that he bought the said tires from Go of

Gold Link in the total amount of 45,500 where he was issued Sales Invoice No. 980.16

Third, the accused knew or should have known that the said article, item, object or

anything of value has been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft. The

words "should know" denote the fact that a person of reasonable prudence and

intelligence would ascertain the fact in performance of his duty to another or would

govern his conduct upon assumption that such fact exists.17 Ong, who was in the

business of buy and sell of tires for the past twenty-four (24) years,18 ought to have known

the ordinary course of business in purchasing from an unknown seller. Admittedly, Go

approached Ong and offered to sell the thirteen (13) tires and he did not even ask for proof

of ownership of the tires.19 The entire transaction, from the proposal to buy until the

delivery of tires happened in just one day.20 His experience from the business should have

given him doubt as to the legitimate ownership of the tires considering that it was his first

time to transact with Go and the manner it was sold is as if Go was just peddling the

thirteen (13) tires in the streets.

In Dela Torre v. COMELEC,21 this Court had enunciated that:

Circumstances normally exist to forewarn, for instance, a reasonably vigilant buyer that the

object of the sale may have been derived from the proceeds of robbery or theft. Such

circumstances include the time and place of the sale, both of which may not be in accord

with the usual practices of commerce. The nature and condition of the goods sold, and the

fact that the seller is not regularly engaged in the business of selling goods may likewise

suggest the illegality of their source, and therefore should caution the buyer. This justifies

the presumption found in Section 5 of P.D. No. 1612 that "mere possession of any goods, . . .,

object or anything of value which has been the subject of robbery or thievery shall be prima

facie evidence of fencing" a presumption that is, according to the Court, "reasonable for

no other natural or logical inference can arise from the established fact of . . . possession of

the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft." xxx.22

Moreover, Ong knew the requirement of the law in selling second hand

tires.1wphi1 Section 6 of P.D. 1612 requires stores, establishments or entities dealing in

the buying and selling of any good, article, item, object or anything else of value obtained

from an unlicensed dealer or supplier thereof to secure the necessary clearance or permit

from the station commander of the Integrated National Police in the town or city where

that store, establishment or entity is located before offering the item for sale to the public.

In fact, Ong has practiced the procedure of obtaining clearances from the police station for

some used tires he wanted to resell but, in this particular transaction, he was remiss in his

duty as a diligent businessman who should have exercised prudence.

In his defense, Ong argued that he relied on the receipt issued to him by

Go.1wphi1 Logically, and for all practical purposes, the issuance of a sales invoice or

receipt is proof of a legitimate transaction and may be raised as a defense in the charge of

fencing; however, that defense is disputable.23 In this case, the validity of the issuance of

the receipt was disputed, and the prosecution was able to prove that Gold Link and its

address were fictitious.24Ong failed to overcome the evidence presented by the

prosecution and to prove the legitimacy of the transaction. Thus, he was unable to rebut

the prima facie presumption under Section 5 of P.D. 1612.

Finally, there was evident intent to gain for himself, considering that during the buy-bust

operation, Ong was actually caught selling the stolen tires in his store, Jong Marketing.

Fencing is malum prohibitum, and P.D. 1612 creates a prima fqcie presumption of

fencing from evidence of possession by the accused of any good, article, item, object

or anything of value, which has been the subject of robbery or theft; and prescribes a

higher penalty based on the value of the 25 property.

The RTC and the CA correctly computed the imposable penalty based on P5,075 for each

tire recovered, or in the total amount of P65,975. Records show that Azajar had purchased

forty-four (44) tires from Philtread in the total amount of P223,40 1.81.26 Section 3 (p) of

Rule 131 of the Revised Rules of Court provides a disputable presumption that private

transactions have been fair and regular. Thus, the presumption of regularity in the ordinary

course of business is not overturned in the absence of the evidence challenging the

regularity of the transaction between Azajar ,and Phil tread.

In tine, after a careful perusal of the records and the evidence adduced by the parties, we

do not find sufficient basis to reverse the ruling of the CA affirming the trial court's

conviction of Ong for violation of P.D. 1612 and modifying the minimum penalty imposed

by reducing it to six ( 6) years of prision correccional.

WHEREFORE, premises considered, the Petition is DENIED for lack of merit. Accordingly,

the assailed Decision of the Court of Appeals in CA-G.R. CR No. 30213 is hereby AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

PEOPLE VS GUZMAN

"Fencing" is the act of any person who, with intent to gain for himself or for another, shall buy, receive, possess, keep, acquire,

conceal, sell or dispose of, or shall buy and sell, or in any other manner deal in any article, item, object or anything of value which he

knows, or should be known to him, to have been derived from the proceeds of the crime of robbery or theft. Is the crime of fencing a

continuing offense of the crime of robbery or theft as to allow the filing of a complaint or information for its commission in the place

where the robbery or theft is committed and not necessarily where the property unlawfully taken is found to have been acquired?

This is the issue resolved in this case the spouses Rudy and Ludy.

The case stemmed from the robbery committed in Quezon City on September 9, 2004 in the house of Mr. Ortega where various

pieces of precious jewelry allegedly worth millions of pesos, were taken. On September 30, 1981 after police sleuthing, the suspects

were identified and charged in the Regional Trial Court (RTC) of Quezon City, Branch 101. Follow up investigation led to the

recovery of the stolen pieces of jewelry from Rudy and Ludy who were found to have possession of them in Antipolo, Rizal. So on

October 22, 1985 an Information for violation of the Anti-Fencing Law (PD 1612) was filed against Rudy and Ludy also before the

RTC of Quezon City, Branch 93.

Rudy and Ludy filed a motion to quash the information filed against them in the RTC of Quezon City. The argued that the Court has

no jurisdiction to try the offense charged because as per police investigation, the crime took place in Antipolo, Rizal. So, the

spouses claimed that the charge should have been filed with the Antipolo RTC within whose jurisdiction the alleged fencing took

place. They reasoned out that fencing is an independent crime separate and distinct from that of Robbery.

The Prosecution opposed the motion to quash, alleging among others that there is nothing in the law which prohibits the filing of a

case of fencing in the court under whose jurisdiction the principal offense of robbery was committed. He theorizes that fencing is a

"continuing offense" and the Anti-Fencing Law was enacted for the purpose of imposing a heavier penalty on persons

who profit from the effects of the crime of roberry or theft, no longer as mere accessories but as principals equally guilty with the

perpetrators of the robbery or theft.

But the RTC of Quezon City agreed with the spouses and quashed the Information filed against them. The RTC said that since the

alleged act of fencing took place in Antipolo, Rizal, outside the territorial jurisdiction of the court, and considering that

all criminal prosecutions must be instituted and tried in the municipality or province where the offense took place, it has no

jurisdiction over the case.

Was the RTC of Quezon City correct?

Yes.

Fencing is not a continuing offense where the commission of robbery or theft is

an essential element. A continuing crime is a single crime consisting of a series

of acts arising from a single criminal resolution orintent not susceptible of

division. For it to exist, there should be plurality of acts performed separately

during a period of time; unity of penal provision infringed upon or violated; unity

of criminal intent or purpose, which means that two or more violations of the

same penal provision are united in one and the same intent leading to the

perpetration of the same criminal purpose or aim.

The crimes of robbery and fencing are clearly two distinct offenses. Robbery is defined and penalized by the Revised Penal Code

(Art.293) as the "taking of the property belonging to another with intent to gain, by means of violence against or intimidation of any

person, or using force upon anything" Fencing is defined and penalized by a special law (PD 1612, Anti-Fencing Law). The law on

fencing does not require the accused to have participated in the criminal design to commit, or to have been in any wise involved in

the commission of, the crime of robbery or theft. Neither is the crime of robbery or theft made to defend on an act of fencing in order