Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Colonial Architecture

Uploaded by

Jean Home0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

156 views14 pagesby Jon Lim

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documentby Jon Lim

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

156 views14 pagesColonial Architecture

Uploaded by

Jean Homeby Jon Lim

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 14

Colonial architecture

#1 Town and Country: Nation's very first town plan.

Jon Lim | 20 March 1991

THE charm of Singapore, by way of its people and usage of buildings, owes much to the origins

of the old city. As such, we need to look more closely at the forces that shaped the original town

plan.

Laid under the guidance of Stamford Raffles after Singapore was founded in 1819, the country's

town plan reflected 180 years of history behind the British, who had planned India's newer cities

since the 1640s.

According to author Anthony King, who wrote the book, Colonial Urban Development In India,

the colonial society consisted of three cultures - the Colonial First, Second and Third Cultures.

The British "at home" in England, whose economies were generated by the Industrial Revolution,

made up the Colonial First Culture.

The natives in the colonies made up the Colonial Second Culture, and belonged to the pre-

industrialised world. The Colonial Third Culture consisted of the expatriates who were

administrators and corporate traders.

INSPIRATION

Raffles wanted Singapore to become a premier centre of trade between the East and West. To

achieve this, the town plan incorporated the needs of the Colonial Second and Third Cultures.

This had to be woven within a common civic entity, yet remain separate in certain areas, for the

sake of development. It was done through the Town Planning Committee. In many ways, the

civic plan of Georgetown, Penang, served as a model of this vision when it was laid out by

Captain Francis Light in 1786.

The Penang town plan provided for a typical British settlement. But, unlike India, the native

towns of the Chinese and Indian immigrants are formal extensions of the town plan.

As a result, the Colonial Second and Third Cultures shared a common civic vision in the plan.

Raffles understood this as he dealt with all races with regard to the maintenance of the township.

He observed that the state of sanitary health in the European and native areas of Georgetown

were generally in a much higher state than expected. This contrasted with colonial cities like

Madras and Calcutta, where the state of sanitary health varied extremely between the British and

native areas. This had something to do with the fact that the bazaars, or native towns, of India

developed separately.

The native streets did not run continuously, neither were they linked by main roads to the areas

of British settlement. In Calcutta during the early 19th century, the native towns were known to

have been forced out in order to make way for extensions of the British settlement. It is arguable

that Raffles saw Georgetown as a model city which shed civic responsibility among its citizens.

Colonial architecture

The core of the town plan of Singapore belonged to that of Georgetown and th e towns of the

Indian eastern seaboard. This layout was dominated by the military installation.

It consisted of a fort and its "field of fire", or maidan, as it is called i n Calcutta. Besides the

barracks and parade grounds, this also included the military cantonment.

The civilians, or Colonial Third Culture, occupied what King calls the "Civil Station". The area

housed the civic administration, but churches, institutions and clubs were also included.

Their business district was set apart from the residential suburb, which was linked to the

recreation areas for sports or gymkhanas, horse racing and polo.

However, Raffles, as State Secretary dealing with the citizens in Georgetown, realised that the

Malay kampungs did not share the same infrastructure with the native (Chinese or Indian) towns.

A similar situation existed in Batavia, or Jakarta, where Raffles acted as Lieutenant- Governor of

Java (1811-1815) following the invasion of Dutch Java by the British in 1810.

Here, the native town belonged to the Batavian Chinese. Their business and residential areas

were combined, and could be regarded as a form of Chinatown.

This was reflected in their urban buildings that conformed to the rigid tow n plan of Batavia, laid

out earlier under Dutch rule.

The Javanese natives tilled the land outside Batavia. Raffles allowed native

affairs and land cultivation to be governed among the natives themselves. It was a liberal policy

endowed with self-enterprise which the Batavian Chinese thrived on under the Dutch, prior to

the mid-18th century.

Although Raffles' land policies failed in Java, the spirit of it was apparently revitalised under the

town development of Singapore.

The citizens of the Malay and Arab world, the Chinese from Fujian and Guangdong, and the

other races prospered under British rule.

PRAGMATISM

When the Dutch re-acquired Java following the Anglo-Dutch treaty, Singapore was founded to

guarantee the safe passage of British trade to China. Not surprisingly, Raffles perceived Singapore

as a fortress against expanding Dutch influence in the region.

It is interesting to note that his direction for the layout of Singapore town appears to be cast in

the mould of Calcutta, where he was earlier stationed in preparation for the invasion of Java.

Calcutta then was dominated by the new Fort William, with its surrounding maidan, and the

River Houghli. This followed a replanning programme when C fell to Maharatta raiders in 1756.

Soon after his arrival in Singapore, Raffles proposed that Bukit Larangan, o r Fort Canning Hill,

be made into a fort. He forbade development within the clearing between the Singapore River

and the eastern coastal plain (the Padang).

Colonial architecture

This open space extended northwards along the present Stamford canal, where an ancient Malay

defensive wall skirted the fresh-water stream.

The Bras Basah Park of today is part of the 200-yard setback of what is believed to be from the

Malay wall or "old lines" referred to by Raffles.

The most familiar feature between Calcutta and Singapore is the relation of the fort to the open

space and river.

Fort Canning, which is bounded by the Singapore River, the Padang and Bras Basah Park, can be

compared to the new Fort William in Calcutta, which was bounded by the maidan and River

Houghli. The use of parklands to encourage the impression of a prosperous city are also shared

between Singapore and Calcutta.

From the Padang, this view includes buildings at the civil station and business districts - Empress

Place, Fullerton Place and Raffles Place, as well as institutional buildings from Bras Basah Park.

This may be compared with the views of Esplanade Row and Dalhousie Square from the maidan,

representing the civic and business districts of Calcutta.

Lieutenant Philip Jackson's town plan of Singapore is based on a proposed development by the

Town Committee under Raffles in 1822. It was the earliest street plan of Singapore which

allowed all citizens a commanding view of Fort Canning and the Civil Station at its foothills.

Natives from Chinatown and the (Indian) Chuliah kampung were served by two streets, namely,

South Bridge Road and New Bridge Road, south of the river.

The residence of the Malay royals was located next to the Bugis and Arab kampung, between the

coast and Rochore River, north of the proposed European town.

They were linked, through North Bridge Road and Victoria Street, to the Civi l Station and the

south side of the Singapore River. The kampung of the Temenggong, which originally stood at

what is now Empress Place, has been relocated to Telok Blangah.

It was, perhaps, no accident that all sections of the native community prospered according to

their allocations in the town plan. This had not been provided for in Dutch Java. For instance,

ethnic trades with the Rhio, Bugis and Indonesian islands existed with the natural harbours at

Rochore.

The Chinese eventually prospered from their entrepot trade at the Singapore River.

The Temenggong not only profited from sales of his property to shipping activities at Telok

Blangah, but also cultivated gambier and spice in Johor.

The proposed town plan shows that business and warehouse area were reserved for the British

from the south bank of the Singapore River to the Telok Ayer bay mark by the Fish Market. This

spread to Collyer Quay, later Telok Ayer Basin after more land reclamation in late 19th century.

Colonial architecture

The British were obsessed with cross-ventilation. The residential suburb at Kampong Glam gave

way to the search for sites atop hillocks by the mid-19th century. Thus, the European town,

marked by Rochore Square, never materialised.

In general, the township of Singapore was a container of cultural diversity. The blueprint of

Singapore's town plan therefore reflect a certain universality of civic vision which belonged to

Raffles.

Jon Lim is a senior lecturer at the National University of Singapore School of Architecture. This

article is based on his PhD thesis (NUS: 1990), Colonial Architecture And Architects Of

Georgetown And Singapore (1786 -1942).

#2 Shophouse tales: they DID NOT originated in China

Jon Lim | 3 April 1991

ORIGINS

AMONG the building types which emerged from Sir Stamford Raffles' town plan of

Singapore, in relation to racial boundaries and military defence, the most unique were the

shophouses of Chinatown.

Contrary to popular belief, Singapore's shophouses are not the same as those in south China.

In fact, the Singapore shophouse owes its origins to Raffles, and can therefore be called

Shophouse Rafflesia.

The term "shophouse" is not found in the English dictionary. It may have bee n literally

translated from Chinese: dian wu in Mandarin, tiam chu in Hokkien, and siong tim and poh

tao in Cantonese.

The vernacular term hong, meaning business house, was used among the English traders in

Guangzhou (Canton) during the 19th century, and originally referred to the local Chinese

trade syndicates that dealt with European traders.

From pictures recorded by European artists, it is evident that China's shophouses are very

different from the "contemporary" ones in Singapore.

Those in China have neither regular shopfronts nor verandahs, or even five-foot ways.

Instead, their facades are made up of a mix of one and two storeys, and vary from shop to

shop. During the hot season, shade is created from rattan or bamboo awnings, or by

stretching a tent of oyster shells across the street.

Even street patterns are different: they do not form grids, as in Singapore, but run in

serpentine rows. These are intercepted by street archways, or pai lou, and courtyards, and are

incidental civic spaces.

In Singapore, the layout of Chinatown forms a grid. Each street represents a cramped

Chinese kampung whose occupants, besides being self-enterprising, depended heavily on

colonial employment.

Colonial architecture

Along the main thoroughfare, the superior and spacious estates of the colonial masters

become apparent. Evidently, the layout of Chinatown and its shophouses reflect the

differences in economic and social stratas of colonial Singapore.

The reverse is true in China, where the European traders were confined to cantonments

(such as those found outside the city of Guangzhou).

SHOPHOUSES, RAFFLES STYLE

Today, one can find rows of Shophouse Rafflesia in the former Chinese Treaty ports such as

Guangzhou, Ningbo, Shanghai and Xiamen. How did they get there?

The sponsors were, in fact, European and Chinese traders from Singapore and South-east

Asia.

On closer study, one can see that Raffles' shaping of the Singapore shophouse was based on

the views he formed from his travels in Asia before he founded Singapore.

Upon leaving England, Raffles first called upon Madras in 1805 and Calcutta in 1810. In

both cities, the "shophouses" were a variety of disjointed bungalows and flat-roof houses

which formed the bazaars. Contemporary artists record no covered public shelters even in

the English town.

In Penang, the shophouses which Raffles saw were basically long rows of single-storey

structures. The platform constituted the floor which was raised on stilts, supporting a hip-

gable roof.

Access to each shopfront was by individual planks placed above a communal ditch. These

buildings served the basic needs of urban shelters, but were hardly permanent.

In Penang, Raffles knew of town fires arising from these structures. Such experiences would

have influenced him to prescribe the use of fire-proof building materials.

In Batavia (Jakarta), where Raffles served as Lieutenant-Governor between 1811 and 1815, a

variety of building types appear to have preceded the shophouse form.

The most common were the godowns of the Dutch East India Company which acted as a

defensive wall in locations along the outer canals of the city. Raised above ground level over

a single-storey base, the upper storey incorporated a continuous verandah behind a row of

stout brick piers.

This supported great lengths of tiled roofs which formed part of the uniform facade.

Obviously, the design of these godowns not only responded to utility, but to climatic needs

as well.

The fire walls that sprouted above roof level existed in the terrace houses at Kali Besar East,

Batavia. This prevented the spread of fires among row development. Construction of similar

walls were later adapted in Singapore's shophouses.

Colonial architecture

At the same time, the Chinese attap shophouses, such as those at the corner of Gang

Kenanga and Passer Senan, Batavia, were more advanced in design than those which Raffles

saw in Penang. These single-storey buildings were distinguished by air wells or courtyards

spaced between large and small gable roofs, running along the depth.

As in the shophouses of south China, there were no five-foot ways in the completely open

and irregular fronts, which were also marked by vertical signboards.

At night, security was obtained by vertical boardings. However, these shophouses did not

convey the rich urban character that the street scenes of south China did. They appeared

along one side of the street, apparently leading to nowhere, and seemed lost in the vast

expanse of space. The buildings here, as in Penang, posed fire hazards.

The most exceptional building type which Raffles would have seen was the terrace houses

which set the scene of the infamous massacre of the Chinese in 1740. This came from

historical records kept by the Batavian Society of Arts, which Raffles revived and later

presided over.

An outstanding detail was the roof apron which ran from corner to corner of the city block,

shading the first storey. This was obviously a utilitarian solution, in addition to the use of

ornaments like those on the roof.

Surprisingly, the use of the roof apron was not commonly adapted to other buildings with

regular fronts. Could Raffles have noted this deficiency in a tropical city like in Batavia?

UNIFORM FRONTS FOR HOUSES

This question seems to be answered in Singapore on Nov 4, 1822, when the Tow n Planning

Committee, under Raffles' direction, stated that "all houses constructed of brick or tile

should have a uniform type of front, each having a verandah of a certain depth, open to all

sides as a continuous and open passage on each side of the street".

This shophouse prototype was documented by J.T. Thomson in his paintings, Singapore

Town From Pearl's Hill (1847) and Singapore Town From Government Hill (1846).

They show a massive housing programme along New Bridge Road between Upper Circular

Road and Pagoda Street, which spills towards the coastal Telok Ayer Bay. What is impressive

is that the shophouses here were not built piecemeal, but covered entire city blocks. This

project was, in effect, a precedent of the modern Singapore housing and development

programme.

Singapore was the first Asian country in which the Shophouse Rafflesia appeared. Similar

shophouses with regular fronts and verandahs in Penang and Malacca appeared only after

1887, following a Municipal Act which defined the town limit.

The shophouses of Bangkok only appeared after the 1870s, and were first introduced by

King Rama V at Bunrung-Mueng Road after his visit to Singapore.

Colonial architecture

Those in Batavia developed from street grids at Glodok and emulated the shophouses in

Chinatown, Singapore.

The shophouses in Phuket appeared after development in Penang, while the one s in the

Chinese quarters of Rangoon, Manila and the Treaty ports of China appeared late in the 19th

century.

The Shophouse Rafflesia originated from a tropical context in Singapore. It was then re-

appropriated by merchants from South-east Asia who spread them along the mercantile

route to China along the Pacific rim.

Thus, Shophouse Rafflesia acquired a seminal status in urban architecture from Singapore.

This conclusion also upturns the commonly held assumption that everything in South-east

Asia came from outside the region.

#3 Storeys of old: Origins of villas and bungalows.

Jon Lim | 1 May 1991

The villa, originally a Roman country house, later became strongly associate d with the

Italian architect, Andrea Palladio. Palladio's villas had the likeness of a Roman temple.

George D. Coleman, who built Singapore's Residency on Fort Canning, also built other

Palladian-style villas. This is apparent from these two paintings of the Padang, dated 1837

and 1851.

SINGAPOREANS today tend to think of a bungalow as simply a detached house se t within

a plot of land. According to the Oxford English dictionary, the word "bungalow" originates

from a Hindi term, bangla, and refers to a single-storey house.

The original bungalow was a humble native shack which was raised on a platform made of

earth. It had a pyramidal thatched roof and was supported with pillars forming a four-sided

verandah.

The British in India took advantage of this native skill by enlarging the bungalow design for

housing their civil and military officers and their families.

This was the Anglo-Indian bungalow, which usually included an upper roof tha t enhanced

indoor ventilation and lighting, as well as a carriage porch.

The landscape around the bungalows was characterised by flower gardens, orchards and

dairy farms.

Large tracts of cheap land were made available to the settlers. Thus, a bungalow estate

represented a colonial world in miniature, a romantic escape from city life.

Indeed, the British expatriates saw themselves as living "in exile in the colonies", and their

estate was compensation for their "state of isolation" in serving king and country.

Colonial architecture

The single-storey bungalows in Bangalore, India, were an eclectic combination of Classical

details with flat and Gothic roof forms.

The roof canopy or "monkey-top" sheltering bay windows, carved in timber fretwork with

scalloped details, were particularly outstanding.

The bungalows in Singapore incorporated either the traditional Malay stilts or European

brick arches. This incorporation later led to the development of the unique two-storey

Anglo-Singaporean, or Anglo-Malayan, bungalows. These had earlier been developed in

Georgetown, Penang.

A drawing of the first European settlement in Singapore, by Lieutenant Phillip Jackson in

1822, showed a predominant collection of Anglo-Indian and some Anglo-Singaporean

bungalows.

Indeed, the early bungalows of Georgetown, such as those recorded by artist James Wathen

in 1811, can be regarded as the ancestor of the now well-loved "black-and-white" bungalows

of Singapore.

One of the earliest of such bungalows in Singapore was recorded by J.T. Thomson in his

painting of Telok Ayer Street in 1846. This black-and-white was lodged between some

shophouses!

Contemporary examples of black-and-whites are seen in Sembawang, Changi and

Goodwood Park, as well as Malcolm and Pender roads - former British enclaves.

A special feature of these bungalows is a verandah-like living room above th e upper space

of the carriage porch.

Two of the original double- storey bungalows from the 19th century have remained mostly

unchanged.

They are Burkill Hall at the Botanic Gardens, which was the Director's bungalow; and Sri

Temasek, the former Colonial Secretary's bungalow, at the Istana grounds.

In both bungalows, the first storey is open except for the four corners, which consist of

staircases and bathrooms.

Upstairs, the dining room is in the centre and leads directly to the bedroom s and verandah-

like living rooms.

The kitchen and servants' quarters are detached outhouses (this was in line with the Anglo-

Indian practice of exerting cultural exclusivity).

The preservation of both bungalows is assured. Currently, Burkill Hall houses the School of

Ornamental Horticulture, but it could be enhanced as a state house or hotel, like the Sri

Carcossa (the former King's House) at Lake Garden in Kuala Lumpur.

Colonial architecture

THE VILLA

The dictionary defines the term "villa" as a Roman country house, complete with farm

buildings. However, by the Renaissance period, the term was strongly associated with the

country houses designed by the Italian architect, Andrea Palladio.

Palladio concluded from his archaeological studies in Italy that ancient Roman domestic

architecture comprised the "pediment and portico style" - that is, it had the likeness of a

Roman temple. He adopted this style, and his houses became universally known as

"Palladian villas".

In England, Renaissance architect Inigo Jones briefly introduced Palladio's style under the

patronage of Charles II during the mid-17th century.

The style was so intensely cultivated by later British monarchs (King George I-King George

III) and their subjects, that it became widely known as the Georgian and Regency styles

during the 18th and early 19th centuries. Hence, Georgian and Regency villas are also

referred to as part of the "Revival style" in the colonies.

In Singapore, the pioneer design of the Palladian or Regency villa was introduced by an

architect called George D. Coleman. He was described by his patron, English merchant John

Palmer, in Calcutta as an "in-genious young artist".

After a brief sojourn in Batavia, he received his first commission in Singapore by Raffles to

design the Residency on top of Fort Canning, in 1822.

According to a painting of the seafront by Barthelemy Lauvergne in 1837, the Residency

showed a likeness to Palladio's Villa Emo (circa 1556) - its central block also had wings.

Lauvergne's painting showed that Coleman's villas and church, which were below the hill,

were designed in the Regency style, with a strong flavour of Roman temple fronts.

The purity of their details may be appreciated with Coleman's other contemporary buildings,

the Armenian Church and Caldwell's House, which still survive today.

Coleman's Armenian Church owes its form to Palladio's Villa Capra, a country house whose

central dome is flanked by Roman temple fronts on all four sides.

Coleman's Caldwell House, which is located on the grounds of the former Convent of the

Holy Infant Jesus in Victoria Street, is strongly influenced by Jerviston House (1782) in

Lanarkshire, England, which was designed by two architect brothers, Robert and James

Adam.

The most interesting feature is the curved or "bow-front" projection used in place of the

Roman temple facade. Coleman could have sourced this from the publication entitled The

Work In Architecture Of Robert And James Adam (1822).

Colonial architecture

The villas documented by Lauvergne in his painting showed a cubic appearance which is

more suited to the dry Mediterranean climate.

It is no wonder that J. T. Thomson's painting of the Padang in 1846 showed a dramatic

change from Coleman's villas, which were dominated by hipped roofs over the skyline. The

villas belonging to Thomas Church, Singapore's Resident Councillor; William Montgomerie,

the Surgeon; and hotelier Gaston Dutronquoy, faced the Padang. Their style is what

Singapore historian Tom H.H.Hancock referred to as "Tropical Renaissance" in 1954. This

particular style exercised the architectural maxim proclaimed by the Roman architect,

Vitruvius: Firmitas, Utilitas and Venustas, meaning "firm design statement, functional

provision and beauty".

The development of tropical-style villas continued up to the '30s. Earlier examples of such

villas include the Indian High Commission in Grange Road, c. 1913 (which features

elements of the Villa Emo form); the Spastic Children's Association of Singapore building in

Gilstead Road, 1927 (which features a Roman temple facade for the front and a curved or

bow-front portico at the rear).

In Singapore and Penang, many rich Chinese either acquired bungalows and villas, which

used to belong to Europeans, or built similar houses for themselves.

This occurred as Europeans vacated the original suburbs of Kampong Glam behind Beach

Road in Singapore, and North Beach at Northam Road in Penang.

These premises were called ang moh lau, meaning "the house of a European". Thus, the

term came to be used by the Chinese freely and interchangeably to mean either a bungalow

or villa.

It was a term denoting wealth and prestige. The new Asian owners also followed the English

custom of naming their properties "Hall", "Lodge" or "Court".

From this arose the popular misconception which still survives today, that a bungalow or

villa is an ang moh lau, built in the European style and set within a spacious compound for

the colonial elite.

#4 Stone feats: Civil engineer architects and their architecture

Jon Lim | 5 June 1991

ORIGINS

TODAY, civil engineers in Singapore are known for their expertise in the computation of

steel and reinforced concrete in construction. They act as consultants to the architects on

building structure.

However, before the Architects Ordinance in England became law in 1931, civi l engineers

also practised as architects.

The pioneer architects of the colonies were military engineers who held all the important

posts in the Public Works and Municipal departments. During the late 19th century, civil

Colonial architecture

engineers who were members of the Institution of Civil Engineers and the Institution of

Structural Engineers in England began filling up posts vacated by the military engineers.

The shortage of qualified architects in the colony made it possible for civi l engineers to

authorise building designs and rely on draughtsmen to complete the job.

Although qualified architects were slowly recruited into Government service, civil engineers

continued to use them as "architectural assistants". This practice went on from 1902 to the

late '20s, and civil engineers got into the habit of claiming credit for work that was not

always theirs.

Things came to a head in 1929 when the Governor, Sir Hugh Clifford, while speaking to the

Legislative Assembly, wrongly attributed the building of City Hall (now the Industrial

Arbitration Court) to the Engineering Department of the Municipality instead of the

Architect's Department.

In the ensuing furore, the habit was discontinued.

Civil engineers did not really make their mark as outstanding architects in Singapore until the

late '20s and '30s. One exception was John Turnbull Thomson, who designed and built the

Horsburg h Lighthouse in 1851. It is the earliest example of a structure resulting from

experiments made on the strength and durability of building materials against the eroding

forces of nature.

Initially, civil engineers did not try to change the prevailing Classical style when concrete and

steel construction was introduced during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. But this

began to change from the late '20s.

The Swiss civil engineer, Heinrich Rudolf Arbenz, departed from the Classica l style in his

shophouse design at Jellicoe Road. The concrete flat roofs are folded into Swiss chalet-like

roofs with balconies and corner towers.

Arbenz also introduced the most modern townhouses in Singapore during the late '30s.

Consisting of box-like apartments with covered garages in the front, this was located at

Bideford Road before it was demolished to make way for the Seiko Headquarters building

during the early '70s.

Another distinguished civil engineer was Emile Brizay, who built the former Ford Detroit

Factory at Upper Bukit Timah Road (now Hume Industries), scene of the British surrender

to the Japanese in 1942.

Here, Brizay used concrete as thin as a shell over the roof structure. The highlight of the

building is the front of the main engine hall, which showed stepped pylons in the Art-Deco

style. Brizay was also known for his modern "white box" houses. A housing estate was

named Brizay Park, after him.

Among Singapore's own civil engineer architects, the partnership of Chung & Wong & its

former associates, namely Chung Swee Poey and Ho Kwong Yew, deserve special mention.

Colonial architecture

The New Asia Hotel at Maxwell Road, opposite the Urban Redevelopment Authority

Building, is one of the earliest and largest reinforced concrete buildings designed by Chung

Hong Woot and Wong Puck Sham. In conservation-conscious Singapore, every effort

should be made to retain this hotel as it complements the Raffles Hotel, which is south of

the Singapore River.

Chung Swee Poey will be remembered for his delightful modern houses, but it is Ho Kwong

Yew who broke new ground. This talented civil engineer echoed the style of functionalism in

modern architecture from France and Germany. His bubble-like Haw Par Villa at Pasir

Panjang was outstanding. Unfortunately, it was bombed by the Japanese in 1942, and the

surviving relic is but the outer concrete walls, displaying rows of spherical balls.

Fortunately, his futuristic shophouse at the corner of Lorong Telok and Circular Road

survived the war, and still have more character than the nearby OCBC building, which was

built during the '70s.

The partnership of Chan Kui Chuan and Tan Koh Keng was active in designing schools in

the Art Deco style. This included the now disused Yock Eng School at Tanjong Katong

Road, the Sun Sun School at Mt Sophia Road, and the Chung Cheng School at Aliwal Street.

#5 From artisans to architects

Jon Lim | 3 July 1991

ORIGINS

TODAY, the National University of Singapore's School of Architecture offers any

Singaporean with the right qualifications the chance to become an architect.

During the colonial days in Singapore, however, formal courses in architecture were not

available to Singapore citizens.

Hence those who wished to become architects had to work as artisans with the Public

Works Department or with self-employed colonial architects.

There was another category of artisans: the craftsmen who complemented the work of

qualified architects.

For instance, the Roman sculptures and columns of the great portico at the Supreme Court

were not produced by architects, but by Cavalieri Rudolfo Nolli, a fourth-generation sculptor

from a well-known Milanese family. Likewise, the magnificent Georgian furniture and

interior of the Supreme Court was designed by William Swaffield, who studied Fine Arts in

Bath, England.

The furniture itself was constructed by the late Yang Ah Kang, who handpicked the

Shanghainese craftsmen to produce the superb woodwork.

Many Singapore architects, such as Bawajee Rajaram, Wan Mohammed Kassim and Yeo

Hock Siang, who built several houses and shophouses, served as draughtsmen, overseers or

surveyors before actually practising as architects.

Colonial architecture

In 1924, William Campbell Oman, then President of the Singapore Society of Architects,

complained that "not one qualified architect could earn a decent living".

He was obviously referring to Singapore architects who received most of the commissions

by the local community. It is clear that a common social background played a part in the

selection of architects by the clients.

The statistics by the Board of Architects in 1928 indicated that the locals were mostly self-

employed and did very well.

Some of the more outstanding Singapore artisans who later became architects were:

* Claude Anthony Eber (1907-88). Eber was born in Singapore. He received his practical

training as a draughtsman while working under the architect and civil engineer partnership of

Westerhout and Oman, and later in the Public Works Department.

After World War II, the colonial government sent Eber to England, where he was admitted

as a Licentiate member of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

His landmark building is the Multi-storey Carpark building at the corner of Market Street

and Cross Street, built in the early '60s. Based on a continuous ramp or spiral system, this is

one of the most user-friendly carparks in Singapore.

He also designed the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation building at Caldecot t Hill, and set

the housestyle for PWD's other works: the National Community Leadership Training

building at South Buona Vista Road, and the former Teacher's Training College at Paterson

Road.

Eber's contributions were important to the development of excellence in PWD architecture

during the mid-'60s.

* Robert Yim Mun Kit was born in China in 1904 and came to Singapore to work as a tracer

for Chung and Wong and became a registered architect by a local special examination in

1948.

During the early '60s, Yim came up with low-cost housing estates with houses that were part

English and part Spanish styled. These were Serangoon Gardens, Opera Estate and Happy

Gardens, off MacPherson Road. He died in 1989.

* Kwan Yow Luen was born in China in 1893. Kwan was a self-taught architect who

practised on his own. His largest work is the former Middle Road Hospital which was called

Doh-jin (c.1943) during the Japanese Occupation. The style is flat and plain, reflecting the

influence of the Modern movement.

However, his design for a mosque (c. 1972) at Tampoi, Johor, is a curious hybrid which

combines the shape of the National Mosque at Kuala Lumpur with a Minangkabau-form

concrete porch. Kwan designed mostly shophouses, and died in 1977.

Colonial architecture

* Ee Hoong Chwee is best remembered for the design of Foo Chow Methodist Church

(1936) at Race Course Road. The entrance porch has Classical columns. Yet all the tall

windows are in th e Gothic style, except for the high vent where round windows reflect the

Classical style.

This facade has unwittingly portrayed the "battle of the styles", which recalls the situation

during the 19th century, when builders in the British Empire were undecided whether civic

buildings should be designed in the Classical or Gothic style.

* Moh Wee Teck was an outstanding architect from the late 19th century. He designed some

of the most ornate villas and shophouses in Chinatown. His best preserved work is a villa

called Golden Bell or Kim Cheng (1908) for Tan Boon Liat at Mount Faber.

The tower, capped with a bell-shaped dome, is counterbalanced by the facade which

displayed a variety of bay windows. Decoration consisted of white pointed brickwork and

star-shaped vents along the roof eaves.

This form of architecture may yet influence the styles of new villas as more old ideas are

revived in Singapore.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Viscous Fluid Flow Frank M White Third Edition - Compress PDFDocument4 pagesViscous Fluid Flow Frank M White Third Edition - Compress PDFDenielNo ratings yet

- RJC 2011 Chem Prelim Paper3ANSDocument12 pagesRJC 2011 Chem Prelim Paper3ANSJean HomeNo ratings yet

- RMHE08Document2,112 pagesRMHE08Elizde GómezNo ratings yet

- SSCNC Turning Tutorial ModDocument18 pagesSSCNC Turning Tutorial ModYudho Parwoto Hadi100% (1)

- Factors Affecting Physical FitnessDocument7 pagesFactors Affecting Physical FitnessMary Joy Escanillas Gallardo100% (2)

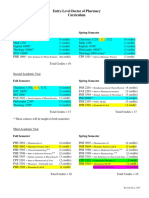

- Pharmd CurriculumDocument18 pagesPharmd Curriculum5377773No ratings yet

- TJC Paper 1 2010Document17 pagesTJC Paper 1 2010Jean HomeNo ratings yet

- RJC 2011 Chem Prelim Paper3Document15 pagesRJC 2011 Chem Prelim Paper3Jean HomeNo ratings yet

- RJC 2011 Chem Prelim Paper2ANSDocument9 pagesRJC 2011 Chem Prelim Paper2ANSJean HomeNo ratings yet

- RJC 2011 Chem Prelim Paper2Document16 pagesRJC 2011 Chem Prelim Paper2Jean HomeNo ratings yet

- Easergy PS100 48VDC Power SupplyDocument2 pagesEasergy PS100 48VDC Power SupplyRichard SyNo ratings yet

- 1ST SUMMATIVE TEST FOR G10finalDocument2 pages1ST SUMMATIVE TEST FOR G10finalcherish austriaNo ratings yet

- Ask A Monk EnlightenmentDocument16 pagesAsk A Monk EnlightenmentPetruoka EdmundasNo ratings yet

- S590 Machine SpecsDocument6 pagesS590 Machine SpecsdilanNo ratings yet

- Pre RmoDocument4 pagesPre RmoSangeeta Mishra100% (1)

- Pref - 2 - Grammar 1.2 - Revisión Del IntentoDocument2 pagesPref - 2 - Grammar 1.2 - Revisión Del IntentoJuan M. Suarez ArevaloNo ratings yet

- In-Service Welding of Pipelines Industry Action PlanDocument13 pagesIn-Service Welding of Pipelines Industry Action Planعزت عبد المنعم100% (1)

- Stanley B. Alpern - Amazons of Black Sparta - The Women Warriors of Dahomey-New York University Press (2011)Document308 pagesStanley B. Alpern - Amazons of Black Sparta - The Women Warriors of Dahomey-New York University Press (2011)georgemultiplusNo ratings yet

- A Presentation On-: Dr. Nikhil Oza Intern BvdumcDocument43 pagesA Presentation On-: Dr. Nikhil Oza Intern BvdumcMaheboob GanjalNo ratings yet

- Southwest Airlines Final ReportDocument16 pagesSouthwest Airlines Final Reportapi-427311067No ratings yet

- Dell W2306C LCD Monitor Service ManualDocument104 pagesDell W2306C LCD Monitor Service ManualIsrael B ChavezNo ratings yet

- Angewandte: ChemieDocument13 pagesAngewandte: ChemiemilicaNo ratings yet

- Kuiz1 210114Document12 pagesKuiz1 210114Vincent HoNo ratings yet

- American University of BeirutDocument21 pagesAmerican University of BeirutWomens Program AssosciationNo ratings yet

- BS746 2014Document22 pagesBS746 2014marco SimonelliNo ratings yet

- Rankine-Hugoniot Curve: CJ: Chapman JouguetDocument6 pagesRankine-Hugoniot Curve: CJ: Chapman Jouguetrattan5No ratings yet

- Frontinus - Water Management of RomeDocument68 pagesFrontinus - Water Management of RomezElfmanNo ratings yet

- A Textual Introduction To Acarya Vasuvan PDFDocument3 pagesA Textual Introduction To Acarya Vasuvan PDFJim LeeNo ratings yet

- Mini-Case 1 Ppe AnswerDocument11 pagesMini-Case 1 Ppe Answeryu choong100% (2)

- Full Download Short Term Financial Management 3rd Edition Maness Test BankDocument35 pagesFull Download Short Term Financial Management 3rd Edition Maness Test Bankcimanfavoriw100% (31)

- Manual 35S EnglishDocument41 pagesManual 35S EnglishgugiNo ratings yet

- Navy Supplement To The DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 2011Document405 pagesNavy Supplement To The DOD Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms, 2011bateljupko100% (1)

- Plato: Epistemology: Nicholas WhiteDocument2 pagesPlato: Epistemology: Nicholas WhiteAnonymous HCqIYNvNo ratings yet

- SCIENCEEEEEDocument3 pagesSCIENCEEEEEChristmae MaganteNo ratings yet

- Typical Section SC 10: Kerajaan MalaysiaDocument1 pageTypical Section SC 10: Kerajaan MalaysiaAisyah Atiqah KhalidNo ratings yet