Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia

Uploaded by

taner_soysurenOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia

Uploaded by

taner_soysurenCopyright:

Available Formats

CE Article #1

Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia in

Dogs:The Lateral Approach for

Surgical Management

Lysimachos G. Papazoglou, DVM, PhD, MRCVS*

F. A. Mann, DVM, MS, DACVS, DACVECC

Jennifer J. Warnock, DVM

Kug Ju Eddie Song, DVM

University of Missouri–Columbia

ABSTRACT: Cricopharyngeal dysphagia occurs in dogs when there is achalasia or asynchrony of the

cricopharyngeal muscle. Differentiation of other causes of dysphagia and preoperative stabilization

of the patient are essential for a successful outcome. Cricopharyngeal myectomy or myotomy using

a lateral or ventral approach is the preferred treatment.

T

he swallowing process may be divided into the cricopharyngeal phase of swallowing, the

oropharyngeal, esophageal, and gastro- thyropharyngeal muscle contracts while the cri-

esophageal phases.1 The oropharyngeal copharyngeal muscle relaxes, allowing passage of

phase of swallowing may be further subdivided the bolus from the pharynx to the esophagus.1

into oral, pharyngeal, and cricopharyngeal At other times, and as soon as the bolus is com-

phases. Impairment of any part of the oropha- pletely transported into the esophagus, the

ryngeal phase of swallowing may result in dys- cricopharyngeal muscle constricts continuously,

phagia. 2 In the oral phase of swallowing, thereby closing the proximal esophagus to pre-

prehension and formation of a food bolus (which vent entrance of air into the esophagus during

is moved to the tongue base) occur.1,2 Oral dys- respiration and to prevent gastroesophageal

phagia is characterized by decreased tongue reflux into the pharynx.

movements and difficulty in bolus accumula- Cricopharyngeal dysphagia (CPD) is an

tion.2 During the pharyngeal phase of swallow- upper esophageal sphincter abnormality that

ing, the bolus is delivered to the caudal pharynx occurs with inadequate relaxation of the

by coordinated contraction of the pharyngeal cricopharyngeal muscle (achalasia) or failure of

muscles.1 Pharyngeal dysphagia is characterized synchronization between pharyngeal contraction

by interrupted movement of the bolus from the and cricopharyngeal relaxation (asynchrony)

oropharynx to the hypophar- during swallowing. 2–5 Esophageal dysphagia

Send comments/questions via email to ynx and by impaired initiation occurs when there is difficulty transporting the

editor@CompendiumVet.com of the involuntary portion of bolus through the esophageal body.2 Gastro-

or fax 800-556-3288. the swallowing reflex.2 During esophageal dysphagia results when there is a

Visit CompendiumVet.com for *Dr Papazoglou is now affiliated

problem transporting the bolus through the cau-

full-text articles, CE testing, and CE with Aristotle University of dal esophageal sphincter.2

test answers. Thessaloniki, Greece. CPD is uncommon in dogs, and its underly-

COMPENDIUM 696 October 2006

Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia in Dogs: The Lateral Approach for Surgical Management CE 697

Case Report

A 1-year-old castrated English cocker spaniel the left pelvic limb and pharyngeal muscles were within

weighing 24.2 lb (11 kg) was referred to the Veterinary normal limits. A percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy

Medical Teaching Hospital, University of Missouri– tube was placed on the left side, and the dog underwent

Columbia, with a history of chronic coughing and left lateral cricopharyngeal myectomy as already

regurgitation after eating. The dog had a low body described.10,20 The resected cricopharyngeal muscle was

condition score (i.e., 2 of 9). The complete blood count submitted for histopathologic examination. The

and serum biochemistry profile results included slight specimen was stained with hematoxylin–eosin, modified

neutrophilia and lymphocytosis. The result of a serologic trichrome, periodic acid–Schiff, ATPase at pH levels of

examination for Ehrlichia canis infection was positive. A 9.8 and 4.3, esterase, nicotinamide adenine

neurologic examination disclosed no abnormalities. An dinucleotide–tetrazolium reductase, acid phosphatase,

acetylcholine antibody titer was within normal limits. alkaline phosphatase, oil red O, and staphylococcal

Thoracic radiography detected a bronchial and protein A conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The

interstitial pattern that was most evident in the left results of histopathology showed moderate variability in

caudal lung lobe. Barium swallow videofluoroscopy myofiber size, with scattered, round atrophic fibers.

showed normal movement of the barium from the oral Abundant endomysial, perimysial, and adipose

cavity to the pharynx. Attempts to propel the bolus into connective tissues were seen. Necrotic fibers were also

the esophagus were unsuccessful because the upper present, and intramuscular nerve branches moderately

esophageal sphincter was not adequately relaxed. A depleted of myelinated fibers were seen. The dog

diagnosis of CPD was made, and the dog was prescribed recovered uneventfully from anesthesia and started

doxycycline (50 mg PO bid for 3 weeks) and discharged enteral feeding via the gastrostomy tube.

from the hospital. The dog was offered ice cubes 12 days after surgery

Seven days later, the dog was readmitted to the and had canned food and water 14 days after surgery

hospital to undergo surgery for CPD. Results of a without showing signs of regurgitation. Forty-five days

clinical examination of the oral cavity and larynx, with after surgery, the owner reported that the dog was eating

the patient under light anesthesia, were normal. Results canned and dry food normally, without regurgitation or

of an intraoperative electromyographic examination of coughing.

ing causes have been attributed to neuromuscular dys- including myasthenia gravis, laryngeal paralysis, and

functions.6–10 The following should be included in the esophageal stricture.21 Of the 45 dogs reported on to

differential diagnosis of dysphagia: space-occupying date, 65% were female and 35% were male. The most

masses, foreign bodies, cleft palate, strictures, traumatic common breeds identified included the cocker spaniel

lesions, and neuromuscular diseases.11 Pharyngeal dys- (20%), springer spaniel (9%), Bouvier des Flandres (9%),

phagia has clinical signs similar to those of CPD, and golden retriever (6.5%), miniature poodle (4%), and

differentiation between these two types of dysphagia is standard poodle (4%). A genetic component of CPD has

very important because surgical intervention for CPD been identified in golden retrievers22 and has been sug-

may worsen pharyngeal dysphagia.12 Positive-contrast gested to exist in cocker spaniels.8,18 In addition, muscu-

videofluoroscopy is reliable in confirming the diagnosis lar dystrophy of hereditary origin has been proposed as a

of CPD and in differentiating the condition from other cause of dysphagia in Bouvier des Flandres.9

causes of dysphagia.8,13

According to the literature, 45 dogs ranging in age SURGICAL ANATOMY

from 5 weeks to 10 years have reportedly had surgery for The cranial esophagus is dorsal to the larynx and left

CPD. 1,6,8–10,14–20 The disorder has reportedly affected of the midline. The upper esophageal sphincter is

mostly young dogs, but cases of older dogs with CPD formed by the thyropharyngeal and cricopharyngeal

have also been reported.8,21 In a recent study21 of 14 dogs muscles. The thyropharyngeal muscles originate from

undergoing surgery for CPD, the median age was 15 the lateral surface of the thyroid cartilage lamina and

months at initial evaluation compared with a median age course dorsally and cranially over the dorsal border of

of 5.5 months for dogs in previous reports.1,6,8–10,14–20 This the thyroid lamina and insert on the median dorsal sur-

age difference as described in the study has been attrib- face of the pharynx in a bilaterally symmetric fashion.

uted to the concurrent existence of acquired disorders, The cricopharyngeal muscle originates from the lateral

October 2006 COMPENDIUM

698 CE Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia in Dogs: The Lateral Approach for Surgical Management

Figure 1. Positioning for the left lateral approach for

cricopharyngeal myectomy or myotomy. The dog is placed

in right lateral recumbency with a rolled towel under its neck. Figure 2. The sternocephalicus muscle (SC) and the

The dog’s head is to the left in this figure.The arrows indicate the jugular vein (arrow) are retracted dorsally. The

jugular vein, and the dotted line indicates the proposed skin sternothyroideus muscle (ST) can be visualized in the ventral part

incision just ventral to the jugular vein. of the incision.

surface of the cricoid cartilage and spreads over the dor- dres with muscular dystrophy undergoing surgery for

sal surface of the esophagus across the midline and ends CPD showed incoordination in the pharyngeal phase of

by narrowing its belly to the contralateral aspect of the swallowing in addition to CPD.9 Aspiration pneumonia

cricoid cartilage. The borders of the cricopharyngeal and and/or bronchitis has been reported in 46% of the 45

thyropharyngeal muscles are obscured as the fibers dogs that underwent surgery for CPD.1,8,10,15–18,21 Laryn-

blend together. 5,23 In contrast to what has been geal paralysis and masticatory myositis have also been

reported,23 recent studies5 in normal puppies and adult reported preoperatively in dogs with CPD.21

dogs have shown that the cricopharyngeal muscle is

unpaired (i.e., single). The cricopharyngeal muscle is Surgical Technique

innervated by the glossopharyngeal nerve and the pha- Cricopharyngeal myotomy or myectomy, alone or

ryngeal branch of the vagus nerve.24 The cricopharyn- combined with thyropharyngeal myotomy or myectomy,

geal muscle receives its blood supply primarily from is the definitive treatment of dogs with CPD to relieve

branches of the cranial thyroid artery. clinical signs and facilitate swallowing. 3,4,6,10,16,21,25,26

During cricopharyngeal myotomy, the muscle is tran-

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT sected along the dorsal midline to the esophageal mus-

Preoperative Considerations and Care cularis.4,6 Cricopharyngeal myectomy involves partial

Preoperative stabilization of dehydrated and debili- excision of the cricopharyngeal muscle after elevating

tated patients is mandatory for a successful outcome4 the muscle fibers from the esophageal muscularis. 3

and includes administration of intravenous fluids and Cricopharyngeal surgery may be performed using the

electrolytes as well as antimicrobials to prevent aspira- standard ventral midline approach. 3,4,6 A lateral

tion pneumonia. To obtain optimal nutritional status, a approach has recently been described for myotomy or

percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube should be myectomy of the cricopharyngeal muscle.10,20,21,26 This

placed in dogs with persistent dysphagia. Electromyog- approach is similar to that used for cricoarytenoid laryn-

raphy of the pharyngeal and laryngeal muscles is useful goplasty in dogs with laryngeal paralysis.27

in excluding other abnormalities associated with the Of the 45 dogs receiving surgical treatment of

pharyngeal phase of swallowing or laryngeal paralysis CPD,1,6,8–10,14–21 53% had cricopharyngeal myotomy, 25%

that may adversely affect the outcome.9,21 Preoperative had cricopharyngeal myectomy, 9% had cricopharyngeal

electromyographic recordings in four Bouvier des Flan- and thyropharyngeal myotomy, and 13% had cricopha-

COMPENDIUM October 2006

Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia in Dogs: The Lateral Approach for Surgical Management CE 699

Figure 3. The thyroid cartilage is identified (grasped Figure 4. The thyropharyngeal muscle (grasped with

with forceps). forceps) and cricopharyngeal muscle (CP) can be easily

identified by dissection of the loose connective tissue

around the thyroid cartilage.

esophagus. The head is stabilized on the table by placing

adhesive tape on the nose. An 8- to 10-cm left lateral inci-

sion is made dorsal to the larynx and ventral to the jugular

vein starting at the cranial aspect of the cricoid cartilage

(Figure 1). The platysma muscle and subcutaneous tissue

are incised. With the use of Gelpi retractors, the ster-

nocephalicus muscle and jugular vein are retracted dorsally

and the sternohyoideus muscle is retracted ventrally to

allow identification of the thyroid cartilage (Figures 2 and

3). The loose connective tissue around the thyroid carti-

lage is dissected free to expose the thyropharyngeal mus-

cle, the cricopharyngeal muscle caudal to it, and the

Figure 5. Cricopharyngeal myectomy by dissection of

esophagus (Figure 4). The thyroid gland may become visi-

the muscle laterally and dorsally to the midline. The ble between the trachea and the sternohyoideus muscle.

cricopharyngeal muscle has been incised dorsally and is grasped The cricopharyngeal muscle is dissected free laterally and

with hemostats to facilitate further dissection and final incision dorsally down to the midline (Figure 5). Small branches of

(dotted line) laterally. the cranial thyroid artery are ligated or electrocoagulated

to control bleeding. Perforation of the esophageal wall is

avoided. A 2- to 2.5-cm portion of the cricopharyngeal

ryngeal and thyropharyngeal myectomy. Of dogs under- muscle is removed and placed in 10% buffered neutral for-

going myotomy or myectomy of both muscles, three had malin for histopathologic examination. Connective tissue

partial myotomy and four had partial myectomy. The is apposed with a continuous pattern of 3-0 absorbable

ventral midline approach was performed in 82% of the suture. Skin closure may be accomplished with a continu-

dogs1,6,8,10,14–21 and the lateral approach in 18%.10,20,21 In ous intradermal pattern using 3-0 absorbable suture, or

one report,19 a ventral approach with 45° rotation to the the skin may be closed with nylon suture or staples.

right was used.

In the lateral approach, the dog is placed in lateral Postoperative Care and Complications

recumbency, and a rolled towel is placed under its neck to The day after surgery, patients should be fed canned

elevate the cricopharynx toward the surgeon (Figure 1). or blenderized food for the first 2 days and gradually

An orogastric tube is preplaced to aid identification of the returned to a normal diet over the next 3 to 4 days.28

October 2006 COMPENDIUM

700 CE Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia in Dogs: The Lateral Approach for Surgical Management

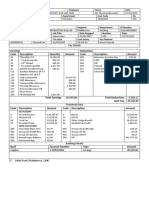

Table 1. Outcome and Follow-up of 45 Dogs Following Surgery for Cricopharyngeal

Dysphagia

Number

of Dogs Outcome Follow-up Studies

22 Complete resolution of clinical signs 1 wk–8 yr Ladlow and Hardie,1 Sokolovsky,6

(21 dogs) Watrous and Suter,8 Peeters et al,9

Niles et al,10 Rosin and Hanlon,14

Shaw and Dodd,15 Quick et al,16

Carlisle and Egger,17 Weaver,18

Allen,19 Pfeifer,20 Warnock et al21

1 The dog was normal besides an occasional cough 3 mo Ladlow and Hardie1

8 Improvement of clinical signs 1 wk–5 yr Watrous and Suter,8 Weaver,18

(five dogs) Warnock et al21

3 Transient resolution of clinical signs (two dogs 2–36 wk Warnock et al21

were euthanized)

3 Died from aspiration pneumonia and concurrent 2 days Peeters et al9

pharyngeal-phase dysphagia

1 Euthanized; aspiration pneumonia, anesthetic 1 wk Watrous and Suter8

stress, exacerbation of dysphagia after surgery

1 Euthanized; persistent dysphagia due to fibrosis 2 wk Rosin and Hanlon14

and contracture

6 Persistent dysphagia associated with concurrent 12 hr–1 mo Warnock et al21

esophageal sphincter structural disease, laryngeal (three dogs)

paralysis, neuromuscular disorders, pharyngeal

disorders, and poor nutritional support

Tube gastrostomy should be considered in patients that may be difficult to manage effectively in the presence of

fail to maintain their body weight after surgery and that esophageal hypomotility and megaesophagus. 21 In a

have persistent dysphagia.21 Fluid therapy and antimi- study9 of 24 Bouvier des Flandres with dysphagia asso-

crobials may be continued in the presence of aspiration ciated with muscular dystrophy, four had surgery for

pneumonia. 28 Postoperative complications following CPD and three died 2 days after surgery because of

cricopharyngeal myotomy or myectomy may include aspiration pneumonia. The concurrent presence of pha-

laryngeal paralysis, fibrosis, esophageal wall perforation, ryngeal dysphagia in those three dogs may have been

recurrence of dysphagia, and pharyngocutaneous fistula- responsible for the unfavorable outcome. One dog expe-

tion.29 Persistent or recurrent dysphagia and aspiration rienced dysphagia attributed to fibrosis and contracture

pneumonia were the most common short- and long- after undergoing cricopharyngeal myotomy for CPD.

term postoperative complications reported in 23 of the The dog underwent endoscopic bougienage without

45 dogs that underwent surgery for CPD.8,9,14,18,21 The much success and was euthanized. 14 Thus some au-

management of aspiration pneumonia may include ad- thors 3,5,18 support performing myectomy rather than

ministration of intravenous fluids and/or antimicrobials, myotomy to ensure complete removal of the muscle

positive-pressure ventilation via tracheostomy tube or fibers and prevent the previously described complica-

oxygen support via nasal tube, nebulization, and tion. However, others4 favor myotomy as long as muscle

coupage.21 Aspiration pneumonia has been diagnosed in fibers are all recognized and transected. Two dogs have

12 dogs, 10 of which died or were euthanatized as a had revision of previous CPD surgery because of partial

result of the complication 12 hours to 4 years after sur- or transient resolution of dysphagia. One dog under-

gery; two dogs survived.8,9,18,21 Aspiration pneumonia went cricopharyngeal, thyropharyngeal, and hyopharyn-

COMPENDIUM October 2006

702 CE Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia in Dogs: The Lateral Approach for Surgical Management

Key Points and excised without difficulty if the esophageal wall is

not traumatized. Five dogs with CPD that had cricopha-

• Diagnosis of cricopharyngeal dysphagia is made with

positive-contrast videofluoroscopy. ryngeal muscle myectomy through the lateral approach

• Cricopharyngeal myectomy via a lateral approach had complete resolution of clinical signs for 2 to 8 years

provides more rapid and easier access than does a after surgery.10 Before surgery, CPD should be accurately

ventral approach for surgical management of differentiated from other causes of dysphagia (e.g., oral

cricopharyngeal dysphagia. or pharyngeal-phase dysphagia and esophageal hypo-

• Accurate preoperative differentiation of motility) to eliminate the possibility of surgical failure

cricopharyngeal dysphagia from pharyngeal and to decrease the chance of aspiration pneumo-

dysphagia and esophageal hypomotility may decrease nia.8,9,21,30 Preoperative stabilization of the patient and

the possibility of surgical failure and aspiration enteral feeding with a percutaneous endoscopic gastros-

pneumonia. tomy tube are essential for a favorable outcome.

REFERENCES

geal myectomy after previously having cricopharyngeal 1. Ladlow J, Hardie RJ: Cricopharyngeal achalasia in dogs. Compend Contin

and thyropharyngeal myotomy with partial resolution of Educ Pract Vet 22:750–755, 2000.

dysphagia, and the other dog had cricopharyngeal 2. Watrous BJ: Clinical presentation and diagnosis of dysphagia. Vet Clin North

Am 13:437–453, 1993.

myotomy twice but experienced recurrent dysphagia 9

3. Rosin E: Cricopharyngeal dysphagia, in Bojrab MJ (ed): Current Techniques

months after the second surgery.21 Other reported18,21 in Small Animal Surgery, ed 4. Baltimore, Williams & Wilkins, 1998, pp

complications have included seroma in two dogs, inci- 145–147.

sional swelling in two dogs, and pharyngeal swelling 4. Goring RL, Kagan KG: Cricopharyngeal achalasia in the dog: Radiographic

evaluation and surgical management. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 4:438–

and stridor in one dog. 447, 1982.

5. Hyodo M, Aibara R, Kawakita S, Yumoto E: Histochemical study of the

OUTCOME canine inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle: Implications for its function.

Acta Otolaryngol 118:272–279, 1998.

Of the 45 dogs that had surgery for CPD, 49%

6. Sokolovsky V: Cricopharyngeal achalasia in a dog. JAVMA 150:281–285, 1967.

showed complete resolution of clinical signs of dyspha-

7. Pearson H: The differential diagnosis of persistent vomiting in the dog. J

gia; follow-up was available for 38 dogs and ranged Small Anim Pract 11:403–415, 1970.

from 12 hours to 8 years.1,6,8–10,14–21 The outcome and fol- 8. Watrous BJ, Suter PF: Oropharyngeal dysphagias in the dog: A cinefluoro-

low-up of 45 dogs are presented in Table 1. Myotomy graphic analysis of experimentally induced and spontaneously occurring swal-

lowing disorders. Vet Radiol 24:11–24, 1983.

achieved complete resolution of clinical signs in 12 dogs

9. Peeters ME, Venker-van Haagen AJ, Goedegebuure SA, Wolvekamp WT:

and myectomy in 11 dogs. However, the type of surgical Dysphagia in Bouviers associated with muscular dystrophy; evaluation of 24

procedure (myotomy versus myectomy) has reportedly cases. Vet Q 13:65–73, 1991.

not had an effect on the outcome,21 nor has surgeon ex- 10. Niles JD, Williams JM, Sullivan M, et al: Resolution of dysphagia following

perience (diplomates versus residents).21 cricopharyngeal myectomy in six dogs. J Small Anim Pract 42:32–35, 2001.

11. Shelton GD: Swallowing disorders in the dog. Compend Contin Educ Pract

Vet 4:607–613, 1982.

CONCLUSION

12. Willard MD: Dysphagia and swallowing disorders, in Kirk RW (ed): Current

Surgery is the preferred treatment of dogs with CPD, Veterinary Therapy XI. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1992, pp 572–577.

and several techniques to resolve clinical signs of CPD 13. Pollard RE, Marks SL, Davidson A, et al: Quantitative videofluoroscopic

have been discussed in the literature. A lateral approach evaluation of pharyngeal function in the dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound

41:409–412, 2000.

has been described for myotomy26 and myectomy10,20,21 of

14. Rosin E, Hanlon GF: Canine cricopharyngeal achalasia. JAVMA 160:1496–

the cricopharyngeal muscle. With the lateral approach, 1499, 1972.

identification of the cricopharyngeal muscle is straight- 15. Shaw DG, Dodd RR: Cricopharyngeal achalasia. Canine Pract 4:33–34, 1977.

forward and the procedure is quicker and easier com- 16. Quick CB, Hankes G, Womer R, et al: Cricopharyngeal achalasia. Auburn

pared with the ventral approach, in which rotation of the Vet 33:90–98, 1977.

larynx by 180˚ and placement of stay sutures to maintain 17. Carlisle WT, Egger EL: Differential diagnosis of persistent dysphagia and

regurgitation in the young. Iowa State Vet 42:14–18, 1980.

rotation are necessary to identify the cricopharyngeal

18. Weaver AD: Cricopharyngeal achalasia in cocker spaniels. J Small Anim Pract

muscle. In addition, with the lateral approach, access to 24:209–214, 1983.

the dorsal midline of the muscle can be easily achieved 19. Allen SW: Surgical management of pharyngeal disorders in the dog and cat.

and the muscle can be laterally and dorsally undermined Probl Vet Med 3:290–297, 1991.

COMPENDIUM October 2006

704 CE Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia in Dogs

20. Pfeifer RM: Cricopharyngeal achalasia in a dog. Can Vet J 44:993–995, 2003.

21. Warnock JJ, Pollard R, Kyles AE, et al: Surgical management of cricopharyngeal dysphagia in dogs: 14

cases (1989–2001). JAVMA 223:1462–1468, 2003.

22. Davidson AP, Pollard RE, Bannasch DL, et al: Inheritance of cricopharyngeal dysfunction in golden

retrievers. Am J Vet Res 65:344–349, 2004.

23. Hermanson JW, Evans HE: The muscular system, in Evans HE (ed): Miller’s Anatomy of the Dog, ed 3.

Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1993, pp 258–384.

24. Venker-van Haagen AJ, Hartman W, Wolvekamp WT: Contributions of the glossopharyngeal nerve and

the pharyngeal branch of the vagus nerve to the swallowing process in dogs. Am J Vet Res 47:1300–1307,

1986.

25. Gourley IM, Leighton RL: Surgical treatment for cricopharyngeal achalasia in the dog. Pract Vet

44:11–14, 1972.

26. Smith MM, Waldron DR: Head and neck surgery, in Smith MM, Waldron DR (eds): Atlas of Approaches

for General Surgery of the Dog and Cat. Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1993, pp 77–121.

27. Lahue TR: Treatment of laryngeal paralysis in dogs by unilateral cricoarytenoid laryngoplasty. JAAHA

25:317–324, 1989.

28. Fossum TW: Surgery of the digestive system, in Fossum TW, Hedlund CS, Hulse DA, et al (eds): Small

Animal Surgery, ed 2. St Louis, Mosby, 2002, pp 274–449.

29. McKenna JA, Dedo HH: Cricopharyngeal myotomy: Indications and technique. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol

101:216–221, 1992.

30. Mason RJ, Bremner CG, DeMeester TR, et al: Pharyngeal swallowing disorders: Selection for and out-

come after myotomy. Ann Surg 228:598–608, 1998.

ARTICLE #1 CE TEST

This article qualifies for 2 contact hours of continuing education credit CE

from the Auburn University College of Veterinary Medicine. Paid subscribers

may purchase individual CE tests or sign up for our annual CE program.

Those who wish to apply this credit to fulfill state relicensure requirements should

consult their respective state authorities regarding the applicability of this program.

To participate, fill out the test form inserted in this issue or take CE tests online and

get real-time scores at CompendiumVet.com.Test answers are available online

free to paid subscribers as well.

1. Achalasia refers to

a. failure of the cricopharyngeal muscle to relax.

b. asynchrony of the cricopharyngeal and thyropharyngeal muscles.

c. failure of the cricopharyngeal muscle to contract.

d. failure of the thyropharyngeal muscle to relax.

2. CPD is an abnormality of the

a. upper esophageal sphincter.

b. lower esophageal sphincter.

c. upper pharyngeal sphincter.

d. esophageal muscle.

3. Which is an unpaired muscle?

a. sternohyoideus c. sternocephalicus

b. thyropharyngeus d. cricopharyngeus

4. Which breed has been identified as having a genetic component to

CPD?

a. Labrador retriever c. golden retriever

b. boxer d. standard poodle

COMPENDIUM October 2006

Cricopharyngeal Dysphagia in Dogs: The Lateral Approach for Surgical Management CE 705

5. Which statement regarding diagnosis of CPD is

incorrect?

a. A diagnosis of CPD can be confirmed by positive-

contrast videofluoroscopy.

b. Positive-contrast videofluoroscopy is not a reliable

method of differentiating CPD from other causes of

dysphagia.

c. Electromyography of pharyngeal muscles may aid in

differentiating CPD from other abnormalities associ-

ated with pharyngeal dysphagia.

d. Electromyography of the laryngeal muscles in dogs

with CPD is useful in excluding laryngeal paralysis,

which may adversely affect patient outcome.

6. The cricopharyngeal muscle originates from the

a. lateral surface of the thyroid cartilage.

b. lateral surface of the cricoid cartilage.

c. medial surface of the thyroid cartilage.

d. medial surface of the cricoid cartilage.

7. Which complication has not been reported in

dogs after surgery for CPD?

a. aspiration pneumonia

b. persistent dysphagia

c. incisional seroma

d. megaesophagus

8. Which statement regarding surgical treatment

of CPD is incorrect?

a. Cricopharyngeal myectomy via a lateral approach has

been reported.

b. Cricopharyngeal myectomy involves resection of the

esophageal mucosa.

c. During cricopharyngeal myotomy, the muscle is tran-

sected along the dorsal midline to the esophageal

muscularis.

d. Thyropharyngeal myotomy has been reported in con-

junction with cricopharyngeal myotomy.

9. Which statement regarding surgical treatment

of CPD is correct?

a. Cricopharyngeal myotomy is more effective than

cricopharyngeal myectomy.

b. Surgeon experience has not been associated with

patient outcome following surgery.

c. Success after surgery is better with Bouvier de Flan-

dres than with cocker spaniels.

d. In dogs, long-term success after surgery is better

with males than with females.

10. During the lateral approach for cricopharyngeal

myectomy or myotomy, which muscle is retracted

dorsally for exposure?

a. sternocephalicus c. sternothyroideus

b. sternohyoideus d. thyropharyngeus

October 2006 COMPENDIUM

You might also like

- CANINE-Cricopharyngeal Achalasia in DogsDocument6 pagesCANINE-Cricopharyngeal Achalasia in Dogstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Laryngeal Disease in Dogs and Cats - An UpdateDocument16 pagesLaryngeal Disease in Dogs and Cats - An UpdateWang EvanNo ratings yet

- Laryngopharyngeal and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment, and Diet-Based ApproachesFrom EverandLaryngopharyngeal and Gastroesophageal Reflux: A Comprehensive Guide to Diagnosis, Treatment, and Diet-Based ApproachesCraig H. ZalvanNo ratings yet

- Fascia Lata Flap To Repair Perineal Hernia in Dogs - A PreliminaryDocument7 pagesFascia Lata Flap To Repair Perineal Hernia in Dogs - A Preliminaryunknowen 22No ratings yet

- A Case of Feline Panleukopenia in Felis Silvestris in Iran Confirmed by PCRDocument4 pagesA Case of Feline Panleukopenia in Felis Silvestris in Iran Confirmed by PCRUsamah El-habibNo ratings yet

- Hérnia TBDocument3 pagesHérnia TBPietra LocatelliNo ratings yet

- Mucocele Pastor de Shetland 38 Casos Aguirre2007Document10 pagesMucocele Pastor de Shetland 38 Casos Aguirre2007Letícia InamassuNo ratings yet

- Byron 2010Document3 pagesByron 2010Rodolfo Aldana M.No ratings yet

- Dysphagia in The Elderly PDFDocument11 pagesDysphagia in The Elderly PDFangie villaizanNo ratings yet

- DDSP FrenulumDocument4 pagesDDSP Frenulumandrea marigoNo ratings yet

- Endoscopically Guided Nasojejunal Tube Placement in Dogs For Short-Term Postduodenal FeedingDocument10 pagesEndoscopically Guided Nasojejunal Tube Placement in Dogs For Short-Term Postduodenal FeedingsoledadDC329No ratings yet

- Ashcraft's HPSDocument5 pagesAshcraft's HPSmiracle ktmNo ratings yet

- FELİNE-Upper Airway Obstruction in Cats Pathogenesis and Clinical SignsDocument7 pagesFELİNE-Upper Airway Obstruction in Cats Pathogenesis and Clinical Signstaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Diagnostic Imaging of Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS)Document6 pagesDiagnostic Imaging of Hypertrophic Pyloric Stenosis (HPS)Putri YingNo ratings yet

- ContentServer - Asp 9Document7 pagesContentServer - Asp 9AlanGonzalezNo ratings yet

- Partial Obstruction of The Small Intestine by A Trichobezoar in A DogDocument5 pagesPartial Obstruction of The Small Intestine by A Trichobezoar in A DogAyu DinaNo ratings yet

- Client Handout-GOLPP Revised1!27!10Document2 pagesClient Handout-GOLPP Revised1!27!10Susi ZapataNo ratings yet

- PEDIATRIC SURGERY - A Comprehensive Textbook For africa.-SPRINGER NATURE (2019) - 631-827Document197 pagesPEDIATRIC SURGERY - A Comprehensive Textbook For africa.-SPRINGER NATURE (2019) - 631-827adhytiyani putriNo ratings yet

- Gastric Dilatation Organoaxial Volvulus in A DogDocument6 pagesGastric Dilatation Organoaxial Volvulus in A DogKrlÖz Ändrz Hërëdîa ÖpzNo ratings yet

- Esophagus: Comments On Embryology of EsophagusDocument14 pagesEsophagus: Comments On Embryology of EsophagusDave AbrahamNo ratings yet

- Case Report AbdomenDocument5 pagesCase Report Abdomensigario hutamaNo ratings yet

- Signs and Symptoms of Abnormal Swallow: Aspiration (Coughing, Choking)Document2 pagesSigns and Symptoms of Abnormal Swallow: Aspiration (Coughing, Choking)Anda DorofteiNo ratings yet

- Swallowing Disorders 2022Document29 pagesSwallowing Disorders 2022Mohammed AhmedNo ratings yet

- 1 PBDocument6 pages1 PBrizalakbarsyaNo ratings yet

- Estudio Endoscopico-Patologico en Estenosis Pilorica Adquirida en GatosDocument8 pagesEstudio Endoscopico-Patologico en Estenosis Pilorica Adquirida en GatosTatiana Ramirez SibocheNo ratings yet

- Navan Ee Than 2015Document7 pagesNavan Ee Than 2015Yacine Tarik AizelNo ratings yet

- Digestive Disease in Brachycephalic DogsDocument33 pagesDigestive Disease in Brachycephalic DogsVitor MolinaNo ratings yet

- Hérnia Talvez ReferenciaDocument9 pagesHérnia Talvez ReferenciaPietra LocatelliNo ratings yet

- Sildenafil Improves Clinical Signs andDocument6 pagesSildenafil Improves Clinical Signs andJuliana Ramos PereiraNo ratings yet

- Veterinary Internal Medicne - 2022 - Appelgrein - Quantification of Gastroesophageal Regurgitation in Brachycephalic DogsDocument8 pagesVeterinary Internal Medicne - 2022 - Appelgrein - Quantification of Gastroesophageal Regurgitation in Brachycephalic DogsRenato HortaNo ratings yet

- Grand Rounds Index UTMB Otolaryngology Home PageDocument12 pagesGrand Rounds Index UTMB Otolaryngology Home Pagegdudex118811No ratings yet

- GIT - Prob 1Document143 pagesGIT - Prob 1anon_181166970No ratings yet

- Gaschen 2008Document9 pagesGaschen 2008JesseNo ratings yet

- A Case of Feline Panleukopenia in Felis Silvestris in Iran Confirmed by PCRDocument5 pagesA Case of Feline Panleukopenia in Felis Silvestris in Iran Confirmed by PCRintan noorNo ratings yet

- Intestinal SubmucosaDocument4 pagesIntestinal SubmucosaNayra Cristina Herreira do ValleNo ratings yet

- Ratnaike2002 Disfagia en Adulto MayorDocument13 pagesRatnaike2002 Disfagia en Adulto MayorAngelica Maria LizarazoNo ratings yet

- Surgical Treatment of Gastrointestinal Motility DisordersDocument47 pagesSurgical Treatment of Gastrointestinal Motility DisordersBolivar IseaNo ratings yet

- Functional Gastrointestinal DisordersDocument126 pagesFunctional Gastrointestinal DisordersCri Cristiana100% (1)

- 09c6 PDFDocument8 pages09c6 PDFlusitania IkengNo ratings yet

- Hypospadias and Megacolon in A Persian CatDocument3 pagesHypospadias and Megacolon in A Persian CatRizki FitriaNo ratings yet

- Boysen, Vru, 2003Document9 pagesBoysen, Vru, 2003stylianos kontosNo ratings yet

- Dysphagia and Oesophageal Carcinoma-Maj (DR) Francis KamunduDocument44 pagesDysphagia and Oesophageal Carcinoma-Maj (DR) Francis KamunduKutemwaNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Heller Myotomy For Achalasia: Robert N. Cacchione, M.D., Dan N. Tran, M.D., Diane H. Rhoden, M.DDocument5 pagesLaparoscopic Heller Myotomy For Achalasia: Robert N. Cacchione, M.D., Dan N. Tran, M.D., Diane H. Rhoden, M.Dgabriel martinezNo ratings yet

- HHS Public Access: Effects of Chin-Up Posture On The Sequence of Swallowing EventsDocument30 pagesHHS Public Access: Effects of Chin-Up Posture On The Sequence of Swallowing EventsMarcia SantanaNo ratings yet

- Trilogy of Foregut Midgut and Hindgut Atresias PreDocument5 pagesTrilogy of Foregut Midgut and Hindgut Atresias PreEriekafebriayana RNo ratings yet

- 13 Esophagomyotomy and Esophagopexy To Create A DiverticulumDocument5 pages13 Esophagomyotomy and Esophagopexy To Create A DiverticulumKatty ZanabriaNo ratings yet

- Surgery Lectures EsophagusDocument22 pagesSurgery Lectures Esophagusj,007No ratings yet

- Pyloric Stenosis - HistoryDocument3 pagesPyloric Stenosis - HistoryHutomo Budi Hasnian SyahNo ratings yet

- Canine Mammary TumorsDocument14 pagesCanine Mammary TumorsFhyrha MyuceNo ratings yet

- Anaesthetic Implications in A Patient With Morquio A SyndromeDocument4 pagesAnaesthetic Implications in A Patient With Morquio A SyndromepamelaNo ratings yet

- Couturier, Vru, 2012Document6 pagesCouturier, Vru, 2012stylianos kontosNo ratings yet

- Retriever: Case Report: Esophageal Obstruction Management in Labrador DogDocument7 pagesRetriever: Case Report: Esophageal Obstruction Management in Labrador DogAde MesakhNo ratings yet

- DR Ackermans Radiographic Challenge April 2015 Website Version1Document15 pagesDR Ackermans Radiographic Challenge April 2015 Website Version1Vet IrfanNo ratings yet

- Aspiration: Definition: The Passage of Secretions Beyond The V.CDocument5 pagesAspiration: Definition: The Passage of Secretions Beyond The V.Cadham bani younesNo ratings yet

- Cleft Palate CaseDocument5 pagesCleft Palate CaseyomifNo ratings yet

- Congenital Bilateral Choanal AtresiDocument5 pagesCongenital Bilateral Choanal AtresiMonna Medani LysabellaNo ratings yet

- Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults: A Case Series and Literature ReviwDocument6 pagesEosinophilic Esophagitis in Adults: A Case Series and Literature ReviwIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Anesthesia of The PigDocument19 pagesAnesthesia of The PigJuan Fernando Calcina IsiqueNo ratings yet

- Xylazine Sedation Antagonized With TolazolineDocument9 pagesXylazine Sedation Antagonized With Tolazolinetaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Treating Bone Deformities With Circular External Skeletal FixationDocument10 pagesTreating Bone Deformities With Circular External Skeletal Fixationtaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Web MedDocument3 pagesWeb Medtaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Veterinary OncologyDocument3 pagesVeterinary Oncologytaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Ultrasonography of The EyeDocument8 pagesUltrasonography of The Eyetaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Traditional Anti Fungal Logic AgentsDocument6 pagesTraditional Anti Fungal Logic Agentstaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Veterinary Medical Resources On The INternetDocument7 pagesVeterinary Medical Resources On The INternettaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Veterinary ControversiesDocument3 pagesVeterinary Controversiestaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- The Pituitary - Adrenal Axis and Pa Tho Physiology of HyperadrenocorticismDocument7 pagesThe Pituitary - Adrenal Axis and Pa Tho Physiology of Hyperadrenocorticismtaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- The Pattern Approach To Logic DiagnosisDocument12 pagesThe Pattern Approach To Logic Diagnosistaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Three-Dimensional Computed Tomography-User - Friendly ImagesDocument5 pagesThree-Dimensional Computed Tomography-User - Friendly Imagestaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Tracheostomy Techniques and ManagementDocument9 pagesTracheostomy Techniques and Managementtaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Small Animal/ExoticsDocument4 pagesSmall Animal/Exoticstaner_soysuren100% (1)

- The Expanding Role of Veterinary TechniciansDocument3 pagesThe Expanding Role of Veterinary Technicianstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Surgical Techniques For Extra Vascular Occlusiion of Tic ShuntsDocument7 pagesSurgical Techniques For Extra Vascular Occlusiion of Tic Shuntstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Supracondylar Femoral Fractures in Adult AnimalsDocument12 pagesSupracondylar Femoral Fractures in Adult Animalstaner_soysuren100% (3)

- Suture MaterialDocument7 pagesSuture Materialtaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Small Animal/ExoticsDocument5 pagesSmall Animal/Exoticstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Systemic Absorption of Topically Administered DrugsDocument8 pagesSystemic Absorption of Topically Administered Drugstaner_soysuren100% (2)

- Susceptibility of Fleas To Control AgentsDocument2 pagesSusceptibility of Fleas To Control Agentstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- SOW-Feeding Management During Sow LactationDocument6 pagesSOW-Feeding Management During Sow Lactationtaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Status Epilepticus-Patient Management and Pharmocologic TheraphyDocument7 pagesStatus Epilepticus-Patient Management and Pharmocologic Theraphytaner_soysuren100% (1)

- Status Epilepticus-Managing Refractory Cases and Treating Out-Of-hospital PatientsDocument7 pagesStatus Epilepticus-Managing Refractory Cases and Treating Out-Of-hospital Patientstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Soft Tissue SurgeryDocument3 pagesSoft Tissue Surgerytaner_soysuren0% (1)

- Small Animal/ExoticsDocument3 pagesSmall Animal/Exoticstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Status Epilepticus-Clinical Features and Pa Tho PhysiologyDocument8 pagesStatus Epilepticus-Clinical Features and Pa Tho Physiologytaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Should I Recommend The Use of Oral GlycosaminoglycansDocument2 pagesShould I Recommend The Use of Oral Glycosaminoglycanstaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Small Animal Oxygen TherapyDocument10 pagesSmall Animal Oxygen Therapytaner_soysuren100% (1)

- SALMON FİSH-Performing Diagnostic Procedures On Salmonid FishesDocument7 pagesSALMON FİSH-Performing Diagnostic Procedures On Salmonid Fishestaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Role of Glutamine in Health and DiseaseDocument8 pagesRole of Glutamine in Health and Diseasetaner_soysurenNo ratings yet

- Flame Retardant and Fire Resistant Cable - NexansDocument2 pagesFlame Retardant and Fire Resistant Cable - NexansprseNo ratings yet

- TC 10 emDocument7 pagesTC 10 emDina LydaNo ratings yet

- 2020 ROTH IRA 229664667 Form 5498Document2 pages2020 ROTH IRA 229664667 Form 5498hk100% (1)

- Birding The Gulf Stream: Inside This IssueDocument5 pagesBirding The Gulf Stream: Inside This IssueChoctawhatchee Audubon SocietyNo ratings yet

- Crime Data Analysis 1Document2 pagesCrime Data Analysis 1kenny laroseNo ratings yet

- BMJ 40 13Document8 pagesBMJ 40 13Alvin JiwonoNo ratings yet

- RRC Group D Notification 70812Document11 pagesRRC Group D Notification 70812admin2772No ratings yet

- 204-04B - Tire Pressure Monitoring System (TPMS)Document23 pages204-04B - Tire Pressure Monitoring System (TPMS)Sofia AltuzarraNo ratings yet

- Electromagnetic Spectrum 1 QP PDFDocument13 pagesElectromagnetic Spectrum 1 QP PDFWai HponeNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Officers - CPD Booklet Schedule PDFDocument5 pagesHealth Promotion Officers - CPD Booklet Schedule PDFcharles KadzongaukamaNo ratings yet

- Behavior Specific Praise Statements HandoutDocument3 pagesBehavior Specific Praise Statements HandoutDaniel BernalNo ratings yet

- Carboset CA-600 - CST600 - CO - enDocument3 pagesCarboset CA-600 - CST600 - CO - enNilsNo ratings yet

- Guides To The Freshwater Invertebrates of Southern Africa Volume 2 - Crustacea IDocument136 pagesGuides To The Freshwater Invertebrates of Southern Africa Volume 2 - Crustacea IdaggaboomNo ratings yet

- Meat Plant FeasabilityDocument115 pagesMeat Plant FeasabilityCh WaqasNo ratings yet

- Guideline On Smacna Through Penetration Fire StoppingDocument48 pagesGuideline On Smacna Through Penetration Fire Stoppingwguindy70No ratings yet

- Pay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountDocument1 pagePay Details: Earnings Deductions Code Description Quantity Amount Code Description AmountVee-kay Vicky KatekaniNo ratings yet

- Business Plan Example - Little LearnerDocument26 pagesBusiness Plan Example - Little LearnerCourtney mcintosh100% (1)

- Lab Manual PDFDocument68 pagesLab Manual PDFSantino AwetNo ratings yet

- Analysis of Pure Copper - A Comparison of Analytical MethodsDocument12 pagesAnalysis of Pure Copper - A Comparison of Analytical Methodsban bekasNo ratings yet

- Itc LimitedDocument64 pagesItc Limitedjulee G0% (1)

- Neurocisticercosis PDFDocument7 pagesNeurocisticercosis PDFFiorella Alexandra HRNo ratings yet

- IPG Or-01 - PTC Train Infrastructure Electrical Safety RulesDocument50 pagesIPG Or-01 - PTC Train Infrastructure Electrical Safety Rules4493464No ratings yet

- Education in America: The Dumbing Down of The U.S. Education SystemDocument4 pagesEducation in America: The Dumbing Down of The U.S. Education SystemmiichaanNo ratings yet

- SGT PDFDocument383 pagesSGT PDFDushyanthkumar DasariNo ratings yet

- REV Description Appr'D CHK'D Prep'D: Tolerances (Unless Otherwise Stated) - (In)Document2 pagesREV Description Appr'D CHK'D Prep'D: Tolerances (Unless Otherwise Stated) - (In)Bacano CapoeiraNo ratings yet

- Fast FashionDocument9 pagesFast FashionTeresa GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Inducement of Rapid Analysis For Determination of Reactive Silica and Available Alumina in BauxiteDocument11 pagesInducement of Rapid Analysis For Determination of Reactive Silica and Available Alumina in BauxiteJAFAR MUHAMMADNo ratings yet

- Present Continuous Exercises Test 1 - Positive Statements ExerciseDocument2 pagesPresent Continuous Exercises Test 1 - Positive Statements Exerciseangel omar peraltaNo ratings yet

- University of Puerto Rico at PonceDocument16 pagesUniversity of Puerto Rico at Ponceapi-583167359No ratings yet

- Notes Marriage and Family in Canon LawDocument5 pagesNotes Marriage and Family in Canon LawmacNo ratings yet